Abstract

Recent studies of organizational behavior have witnessed a growing interest in unethical leadership, leading to the development of abusive supervision research. Given the increasing interest in the causes of abusive supervision, this study proposes an organizing framework for its antecedents and tests it using meta analysis. Based on an analysis of effect sizes drawn from 74 studies, comprising 30,063 participants, the relationship between abusive supervision and different antecedent categories are examined. The results generally support expected relationships across the four categories of abusive antecedents, including: supervisor related antecedents, organization related antecedents, subordinate related antecedents, and demographic characteristics of both supervisors and subordinates. In addition, possible moderators that can also influence the relationships between abusive supervision and its antecedents are also examined. The significance and implications of different level factors in explaining abusive supervision are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Abusive supervision—“subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact” (Tepper 2000)—is an extremely salient phenomenon in organizations (Tepper et al. 2006). Schat et al. (2006) estimated that more than 13.6 % of employees have observed abusive supervision at work, or have directly experienced it from their immediate supervisor. Numerous surveys have found that that 65–75 % of employees reported that their boss was the worst part of their jobs in any given organization (e.g., Hogan and Kaiser 2005). The consequences of abusive supervision include increased healthcare costs, workplace withdrawal, and lost productivity (Tepper et al. 2006). It is important to understand how organizations can minimize the occurrence of abusive supervision. Therefore, investigating the antecedents of abusive supervision is both necessary and urgent.

Although the consequences of abusive supervision are well known, its antecedents initially received less research attention (Martinko et al. 2013). The seminal work on abusive supervision by Tepper (2000) investigated the consequences of abusive supervision. Most subsequent studies continued this focus and also examined moderators of the effects of abusive supervision (e.g., Harris et al. 2005; Inness et al. 2005; Tepper et al. 2001, 2004). A recent meta-analysis summarized the research findings on the consequences of abusive supervision (Schyns and Schilling 2013).Footnote 1 However, a meta-analytic review of the antecedents of abusive supervision has not yet been produced. Until 2007, Tepper (2007) only identified three studies on the antecedents of abusive supervision in his review.

Empirical research on the antecedents of abusive supervision only started to proliferate during the last 5 years (e.g., Harris et al. 2011; Liu et al. 2012; Wu and Hu 2009). This growth likely resulted from earlier research findings that abusive supervision has a deleterious effect on employees, including their in role performance (Harris et al. 2007), well-being (Lin et al. 2013), and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB; Zellars et al. 2002). As the outcomes of abusive supervision have now been well studied, a continued focus on its consequences is unlikely to yield strong theoretical contributions. Thus, an increasing number of scholars have shifted their attention from the consequences of abusive supervision to its antecedents (Martinko et al. 2013; Tepper et al. 2011).

Although two narrative reviews of abusive supervision antecedents have been published (Martinko et al. 2013; Tepper 2007), a quantitative analysis of antecedents is still lacking. A meta-analysis provides at least three advantages over narrative reviews. First, meta-analysis provides a systematic process for collecting primary studies and applying inclusion criteria. This process ensures a near exhaustive coverage of the relevant literature on the topic of the meta-analysis. Second, meta-analysis combines findings from previous studies, and tests the relationship between the variables of interest. In doing so, inconsistent findings can be analyzed, quantified and ultimately resolved. Third, meta-analysis enables sample level moderators to be tested, in order to explain any heterogeneity in findings across studies. Ultimately, meta-analysis provides greater reliability and generalizability of results, and may yield theoretical insights that are not apparent in individual studies.

The objectives of this meta-analysis are fourfold. First, this meta-analysis empirically tests the relationships between abusive supervision and its antecedents in previous studies, so that the inconsistent findings across studies can be resolved. Second, this meta-analysis tests a set of moderators thought to influence the relationship between abusive supervision and its antecedents. Third, based on the insights previous reviews (Martinko et al. 2013; Tepper 2007) and findings from this meta-analysis, a theoretical framework is proposed. Finally, this meta-analysis builds on previous reviews of abusive supervision by focusing specifically its antecedents. As most research has examined the consequences of abusive supervision (Schyns and Schilling 2013), a meta analysis of its antecedents is urgently needed to balance the research.

Antecedents of Abusive Supervision: a Proposed Theoretical Framework

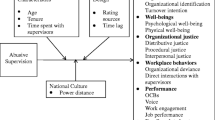

This paper builds on the theoretical framework proposed in the reviews carried out by Tepper (2007) and Martinko et al. (2013). The antecedents of abusive supervision can broadly be categorized into supervisor related antecedents, organization related antecedents, subordinate related antecedents and demographic characteristics of supervisors and subordinates. Figure 1 presents the theoretical model. Variables in this model were selected according to the empirical research conducted so far on the antecedents of abusive supervision.

Supervisor related antecedents comprise constructs based on supervisors’ characteristics, including supervisors’ state, leadership style and personality traits (Aryee et al. 2007; Hoobler and Brass 2006). Aggressive norms and the use of sanctions are classified into organization related antecedents as these variables describe the characteristics of an organization (Restubog et al. 2011). Subordinate related antecedents include employees’ personality traits and cultural characteristics (Lian et al. 2012a). Although empirical studies normally use demographic variables of supervisors and subordinates as control variables, the previous meta analysis of the relationships between demographic variables and workplace aggression showed that there are significant relationships between demographic variables and workplace aggression (Bowling and Beehr 2006). Focusing on abusive supervision as a specific type of workplace aggression, this study investigates the role of demographic characteristics. In theorizing that demographic characteristics produce unique effects, they are neither classified into supervisor related antecedents nor subordinate related antecedents, but rather placed into an independent category.

Supervisor Related Antecedents

Stressors and Negative Affective State

Supervisors’ interactions with higher organizational levels influence their affective state and behavior towards their subordinates (Hoobler and Hu 2013). As Aryee et al. (2007) trickle down model suggests, unequal treatment stemming from higher levels of the organization influences supervisors and consequently subordinates. Moreover, supervisors’ negative states can also result from negative interactions with their co workers. Harris et al. (2011) found that supervisors who experienced more co worker conflicts engaged in greater abusive behavior towards their subordinates. The relationship between supervisors’ affective states and abusive supervision can be explained by research on displaced aggression, which holds that people tend to be aggressive to one party because they were mistreated by another party (Hoobler and Brass 2006; Restubog et al. 2011). Compared with other people in the organization, subordinates are a relatively safe target to vent supervisors’ negative state since subordinates have low retaliatory power (Tepper et al. 2006). For supervisors who regularly experience such stressors, abusing subordinates is an emotion focus coping strategy to alleviate the negative state and stress. On the contrary, supervisors with more positive affective state will be less likely to display abusive behaviors due to their relatively less need to cope with stress. In the current limited number of studies, the focus is on organizational justice of supervisors’ positive state. Colquitt et al. (2013) proposed an affect based perspective to understand the relationship between organizational justice and its outcomes. Supervisors, who have more positive affect, may behave less abusively (Colquitt et al. 2001). Hence the following hypothesis is presented:

Hypothesis 1a

Abusive supervision is positively related to stressors that produce a negative affective state (supervisors’ negative experiences, supervisors’ negative affect, supervisor stress, and lack of interactional and procedural justice).

Supervisor Leadership Style

Based on the definition of (Yukl 2006, p. 8), supervisors organize subordinates to accomplish shared objectives. Leadership style is a stable characteristic of a supervisor (Colbert et al. 2012). Abusive supervision reflects the perception regarding to what extent supervisors engage in sustained displays of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact (Tepper 2000, p. 178). Therefore, when a supervisor adopts a certain type of leadership, s/he will behave in line with his/her leadership style (DeRue et al. 2011). A supervisor with a destructive orientated leadership style will manifest more hostile behavior, such as ridiculing subordinates publicly or taking credit for their work (Schyns and Schilling 2013, p. 141). In contrast, supervisors with constructive orientated leadership are supportive in helping employees to achieve common shared goals (Yukl 2006). Consequently, they will display less abusive behavior.

Hypothesis 1b

Abusive supervision is positively related to destructive leadership (authoritarian leadership style and unethical leadership) but negatively related to constructive leadership (ethical leadership, supportive leadership and transformational leadership).

Supervisor Characteristics

In the current literature, scholars have investigated the role of three types of supervisor characteristics: supervisors’ power, supervisors’ emotional intelligence and supervisors’ Machiavellianism. Supervisors have the capacity to influence subordinates by allocating resources or administering punishments (Lian et al. 2013). Power asymmetry gives supervisors ample opportunities to abuse their subordinates, thereby increasing employees’ perception of abusive supervision (Aryee et al. 2007). Supervisors with high emotional intelligence have better ability to regulate their negative emotions by using effective regulation strategies (Johnson and Spector 2007; Wong and Law 2002). Consequently, these leaders are less likely to unleash their negative emotions, which would be perceived as abusive by their subordinates. Moreover, by using more effective regulation strategies, these supervisors will feel less exhausted when they regulate their emotions (Grandy and Starratt 2010). Due to lower resource loss, they are less likely to abuse their subordinates (Lian et al. 2013). Highly Machiavellian supervisors have the tendency to manipulate and exploit others. Kiazad et al. (2010) drew on the general aggression model (GAM) to explain the relationship between Machiavellianism and abusive supervision. The GAM states that certain traits predispose individuals to engage in aggressive behavior. Therefore, supervisors’ Machiavellianism is a trait which can increase the possibility of exhibiting more aggressive behavior towards subordinates.

Hypothesis 1c

Abusive supervision is related to supervisors’ power, emotional intelligence and Machiavellianism.

Organizational Antecedents

Tepper (2007) suggested that organization norms are a potential antecedent of abusive supervision. In this meta analysis, two organization level antecedents: aggressive norm and organizational sanctions against aggression are found to be in line with Tepper (2007) proposition. Aggressive norm is defined as a shared perception that organization deviance is a permissible means of expressing outrage and resentment (Tepper et al. 2008). Based on social learning theory (Bandura 1973), Restubog et al. (2011) argued that subordinates adopt hostile patterns of behavior if they perceive their supervisors as abusive, especially if they regard the aggressive norm as ubiquitous. Organizational sanctions refer to the extent to which the organization’s authorities stress and enforce the notion that workplace aggression should be completely banned (Dupre 2005). When an organization has strict rules to punish workplace aggression, supervisors are less likely to display aggression towards their subordinates because of the likely penalties that will ensue (Dekker and Barling 1998). Hence the following hypothesis is offered:

Hypothesis 2

Abusive supervision will be positively related to a negative organizational climate (aggressive norm), but negatively related to a positive organization climate (organizational sanctions against aggression).

Subordinate Related Antecedents

Most studies of abusive supervision have measured it according to subordinates’ perceptions of their supervisor’s behavior (e.g., Tepper 2000) rather than through objective measurement. Whether perceived abusive supervision is real or imagined, subordinates’ traits shape their interpretation of their supervisors’ actions (Martinko et al. 2013). Highly cynical employees tend to perceive others’ behavior as more aggressive, even when it is not (Tepper et al. 2006). Employees’ cynical attribution of others’ aggression is an extrapunitive mentality where people tend to project blame onto others rather than on themselves (Hoobler and Brass 2006). If subordinates habitually attribute negative events to external factors, they will be more likely to perceive their supervisors as abusive. In particular, when employees perceive their supervisors’ behavior as being relatively stable (i.e., as trait like aggression), they are more likely to report abusive supervision (Martinko et al. 2011). In line with this attribution argument, Aquino and Thau (2009) stated that people with highly negative affectivity will selectively recall more negative events than people with low negative affectivity. Individuals with high negative affectivity are more prone to classify the ambiguous behavior of supervisors as abusive supervision, and report more victimization (Tepper et al. 2006).

In addition, subordinates’ cultural characteristics have been examined in recent years (Lian et al. 2012a; Lin et al. 2013). Scholars have focused on power distance and traditionalism since both constructs reflect employees’ acceptance of the unequal distribution of power and respect of authority in organizations (e.g. Kernan et al. 2011). Employees with such cultural values are likely to believe that the abuse from their supervisors is acceptable since it reflects supervisors’ power. However, employees with low power distance or nontraditional cultural values have a more egalitarian orientation, and perceive a higher degree of abusive supervision.

Political skill is another personal trait which has been studied in previous years. Employees with high political skill have been shown to be highly effective in implementing certain political tactics, such as ingratiation (Ferris et al. 2010). Such tactics can be used to gain control over interactions with their supervisors (Harrell-Cook et al. 1999). Thus, those highly political skilled employees will be less likely to suffer from abusive supervision due to their relatively higher control.

Personality includes another group of variables which have direct effects on the perception of abusive supervision. Less emotionally stable personalities—particularly those characterized by narcissism and neuroticism—are more sensitive to others’ behavior (Bamberger and Bacharach 2006). In contrast, people who are high on conscientiousness, extraversion and agreeableness have less of a tendency to blame others for negative events (Tepper et al. 2001). In turn, such people are less likely to perceive ambiguous behavior as abusive supervision.

Hypothesis 3

Abusive supervision is related to subordinates’ traits (stability, cynical attribution, negative affectivity, power distance, supervisor directed attribution, traditionalism political skill, narcissism, neuroticism, conscientiousness, extraversion and agreeableness).

Demographic Characteristics of Supervisors and Subordinates

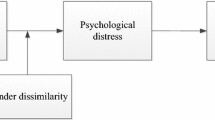

Demographic characteristics of supervisors and subordinates are often treated as control variables in abusive supervision research (e.g., Bamberger and Bacharach 2006; Chi and Liang 2013; Harvey et al. 2007). Typically, the correlations between supervisors’ and subordinates’ demographic characteristics and abusive supervision are relatively low (Mayer et al. 2012). However, some demographic characteristics have been theorized to influence subordinates’ experiences and perceptions of abusive supervision. Research has consistently found that younger supervisors tend to engage in more aggressive behavior (Barling et al. 2009). This pattern may be due to older people having better capabilities in regulating their negative emotions (Gross et al. 1997). Moreover, younger workers tend to behave more aggressively than older workers do. Consequently, they are more likely to become both aggressors and targets of aggression (Felson 1992). Generally, older employees are treated with more dignity and respect than younger workers are. In a similar vein, employees with shorter tenure are more likely to be subjected to abuse than are employees with longer tenure. Subordinates will get used to supervisors’ behavior if they have a longer working relationship; the ambiguous behaviors of the supervisor are less likely to be interpreted as abusive. Demographic dissimilarity between supervisors and subordinates also leads to some negative results. People tend to favor others who exhibit greater similarity and be more derogatory toward others who appear to be dissimilar (Tepper et al. 2011). Thus, demographic differences increase the chance that ambiguous behavior will be interpreted as abusive supervision. Hence the following hypothesis is offered:

Hypothesis 4

Demographic characteristics of supervisors and subordinates (supervisors’ age, subordinates’ age, subordinates’ organizational tenure, working time with supervisors and gender dissimilarity between subordinates and supervisors) are related to abusive supervision.

Moderators of Abusive Supervision Antecedents Relationship: Demographic Variables

Aquino and Thau (2009) suggested that research on the moderating effect of demographic variables between workplace aggression and its correlates would be valuable and fruitful. Gender, organizational tenure, working time with supervisor and age are normally included in abusive supervision literature, but more importantly, established theory provides a conceptual rationale for their role as moderators (Olafsson and Johannsdottir 2004). Previous research also provides evidence for the moderating effect of demographic variables. Smith et al. (2001) found that gender moderates the relationship between emotional coping strategy and bullying. Females are more likely to report ‘crying’ or asking ‘friends/adults for help’ than are males, thereby accessing greater social support. Employees with longer organizational tenure have a higher chance of receiving social support, which decreases the possibility of their being abused (Conway and Coyle-Shapiro 2012). In regard to working experience with supervisors, as previous research on confirmation bias suggests (Nickerson 1998), people process interactional information differently depending on the strength of their relationship with their counterpart. Thus, compared to relatively new employees, employees who have worked a long time with their supervisors may rely on different information when they rate their supervisors’ score on abusive supervision, and are more likely to suffer from confirmation bias (i.e. seeing what they want to see). Accordingly, demographic variables will have a significant impact on the relationships between abusive supervision and its antecedents. Thus, the following hypothesis is provided:

Hypothesis 5

The demographic variables of subordinates’ gender, organizational tenure, working time with supervisors, and age will moderate the relationships between abusive supervision and its antecedents.

Moderator of Abusive Supervision Antecedents Relationship: Research Design

In leadership research, the research design is often considered as a moderator between leaders’ characteristics and their correlates (Gerstner and Day 1997). The measurement processes of abusive supervision potentially affect the relationship between predictors and abusive supervision. This meta-analysis distinguishes between two study characteristics. First, it compares findings from studies in which abusive supervision and its antecedents are measured simultaneously, versus studies in which they are measured at different points in time. Second, it compares studies in which ratings of abusive supervision and its antecedents are provided by a single source, versus studies in which they are rated by different people. Based on a non-concentric perspective on common method variance, the relationship between each predictor and abusive supervision will be stronger if both variables are measured without a time lag and from different sources (Richardson et al. 2009). Self-reports may be distorted in the presence of negative affectivity, social desirability and acquiescence (Podsakoff et al. 2003). With same source/method data, common method variance is likely to affect both correlates within a given study, thereby inflating the observed correlation (Williams and Anderson 1994). Hence the following hypothesis is presented:

Hypothesis 6

Research design (data source and time lag) will moderate the relationship between antecedents of abusive supervision and abusive supervision.

Method

Literature Search and Inclusion Criteria

We used two search approaches to collect prior empirical studies that examined the consequences of abusive supervision. First, we searched the databases Web of Science (SSCI), EBSCO, ABI/INFORM, ERIC, PsycINFO, Google Scholar and Scopus for studies containing “abusive supervision” in their titles, abstracts and keywords. Second, we obtained studies from the reference lists of recent qualitative and quantitative reviews of abusive supervision (Martinko et al. 2013; Schyns and Schilling 2013; Tepper 2007). In addition, we used Web of Science and Google Scholar to obtain studies that had cited two key references (Tepper 2000, 2007). We chose Tepper (2000) as it was the first paper to propose abusive supervision as a construct, and many subsequent studies have adopted its measure of abusive supervision. Tepper (2007) was also chosen as it was the first review of the abusive supervision literature. We also manually checked all issues of the Journal of Emotional Abuse to find any paper that included “abusive supervision” from 2000 to 2014. We did so because this journal is not covered by any of the aforementioned databases, but it is highly relevant to “abuse” research. One study was obtained from this journal (Yagil 2006).

In order to address the issue of publication bias, we searched ‘grey literature’ following the suggestions of Rothstein and Hopewell (2009). These were searched in PsycINFO/Dissertation and ProQuest, as well as reports, book chapters, working papers and conference papers in SCOPUS, PsycINFO and Web of Science (SSCI). Ten theses, book chapters and conference papers were included in our final analysis. In addition, in order to collect unpublished articles or working papers about abusive supervision, we distributed the information about this meta analysis on the email listservs of Human Resources and Organizational Behavior Divisions at the Academy of Management Conference.

Additionally, it is important to note that several studies utilized the same sample. Under these circumstances, repeated findings were only included once in this meta analysis in order to ensure that the assumption of independence was not violated (e.g. Tepper 2000, 2007). Moreover, some studies used more than one sample (e.g. Shoss et al. 2013; Thau and Mitchell 2010). In this situation, each sample was included in the meta-analysis. After excluding studies without the variables in our hypotheses, 74 studies were included in the final meta analysis.Footnote 2

Studies were included if they fulfilled four requirements: (1) abusive supervision was consistent with the definition proposed by Tepper (2000) or the measure of abusive supervision was based on, Tepper (2000) (2) the study included a measure of abusive supervision, (3) the study included a variable that was conceptualized as an antecedent of abusive supervision or a moderator, and (4) zero order correlations were reported.

Coding Procedure

Categorization of Antecedent

Two researchers independently examined variable names, construct definitions and measures used in the primary studies. They then generated categories of antecedents of abusive supervision. Variables were then classified into subcategories based on the frameworks of Martinko et al. (2013) and Tepper et al. (2007).Footnote 3 For the variables which could not easily be classified, the two researchers either created a new category or combined small categories based on conceptual similarity (Conger 1998). For example, a category “Aggressive norm” includes variables that convey the idea that deviant behavior in the organization is appropriate and normal, such as the likelihood of being rewarded for deviant behavior, hostile climate, and co worker aggressive modeling. Together, agreement was reached about the category labels, definitions and associated predictors. Inter rater agreement (Cohen’s kappa = 0.86) shows the coding agreement is sufficient. Table 1 depicts all constructs and constructs names in primary studies that were summarized under each category.

Coding of Effect Sizes

After finalizing our list, relevant effect sizes were extracted from each study. Sample sizes and observed correlations were coded. Based on reported reliability coefficients, the observed correlations were transformed into corrected correlations (Hunter and Schmidt 2004). When the same sample was used in multiple studies, each effect size was only included a single time in order to avoid double counting.

Analysis

For hypotheses 1–4, random effects meta analyses was applied to analyze the data based on the suggestions of Borenstein et al. (2011) and Hunter and Schmidt (2004). The numbers of independent effect sizes (k), the total number of participants across studies (N), the weighted mean correlation (r) and the 95 % confidence interval for the mean effect are reported. Moreover, three statistics to quantify heterogeneity are reported: the weighted sum of squares and its associated p value (the Q statistic); the standard deviation of true effect sizes (T); and the proportion of dispersion that can be attributed to real differences in effect sizes as opposed to within study error (I). For hypothesis 5, four potential moderators are posited in order to account for heterogeneity in the relationship between abusive supervision and its antecedents. Random effects meta regression was employed to test this hypothesis. For hypothesis 6, a subgroup (moderator) analysis is reported based on differences in two research design factors (Borenstein et al. 2011). These factors include: (1) the source of data (self reported vs. others reported), and (2) the time lag between the measurement of abusive supervision and its antecedents (measured concurrently vs. at different time points).

Results

Antecedents of Abusive Supervision

Based on hypothesis 1a, we examined relationships between abusive supervision and supervisors’ negative affective states and stressors. These antecedents included supervisors’ negative experiences, negative affect, stress, perceived lack of interactional and procedural justice. As reported in Table 2, the results provide general support for hypothesis 1a, as abusive supervision is positively related to supervisors’ negative experiences \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.28} \right)\), negative affect \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.33} \right)\) and stress \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.16} \right)\). Moreover, it is negatively related to supervisors’ perceived interactional justice \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.43} \right)\) and perceived procedural justice \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.21} \right)\). All 95 % confident intervals exclude zero {except for negative affect [–0.05, 0.63]}, indicating that most of these relationships are significantly different from zero. Thus, hypothesis 1a is largely supported.

Hypothesis 1b proposes there is a positive relationship between abusive supervision and destructive leadership, and a negative relationship between abusive supervision and constructive leadership. In support of hypothesis 1b, the results show that both authoritarian leadership \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.49} \right)\) and unethical leadership \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.58} \right)\) are positively related to abusive supervision. In contrast, all constructive leadership styles, including ethical leadership \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.57} \right)\), supportive leadership \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.53} \right)\), and transformational leadership \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.45} \right)\) are negatively related to abusive supervision. All 95 % confident intervals excluded zero, indicating all of the relationships are significantly different from zero. Consequently, hypothesis 1b is supported.

Hypothesis 1c argued that supervisors’ emotional intelligence would be negatively related to abusive supervision, while supervisors’ power and Machiavellianism would be positively related to abusive supervision. In support of the hypothesis, supervisors’ emotional intelligence is negatively related to abusive supervision \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.43} \right)\) and the 95 % confidence interval excluded zero. However, the effects of supervisors’ power and Machiavellianism failed to reach significance \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.03\;{\text{for}}\;{\text{power}},\;\bar{r} = 0.29\;{\text{for}}\;{\text{Machiavellianism}}} \right)\) as both their 95 % confidence intervals included zero. In summary, hypothesis 1c is partially supported.

To test hypothesis 2, the relationships between abusive supervision and aspects of organizational climate were tested. The results show that abusive supervision is positively related to aggressive norm \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.38} \right)\) and negatively related to organizational sanction \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.32} \right)\). Both 95 % confident intervals excluded zero, indicating both of the relationships are significantly different from zero. Thus, hypothesis 2 is supported.

To test hypothesis 3, we examined the relationships between abusive supervision and subordinates’ characteristics, including political skill, stability, cynical attribution, negative affectivity, power distance, supervisor directed attribution, traditionality, narcissism, neuroticism, conscientiousness, extraversion and agreeableness. Results showed that abusive supervision is positively related to subordinates’ political skill \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.21} \right)\), cynical attribution \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.13} \right)\), negative affectivity \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.32} \right)\), power distance \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.26} \right)\) and supervisor-directed attribution \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.39} \right)\), while negatively related to subordinates’ stability \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.08} \right)\) and traditionality \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.14} \right)\). For subordinates’ personality, narcissism \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.32} \right)\) and neuroticism \(\left( {\bar{r} = 0.10} \right)\) are positively related to abusive supervision, while conscientiousness \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.06} \right)\), extraversion \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.01} \right)\) and agreeableness \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.16} \right)\) are negatively related to it. Inspection of the 95 % confident intervals revealed that the effects of negative affectivity, power distance, narcissism, conscientiousness, extraversion and agreeableness were significantly different to zero. Thus hypothesis 3 is partially supported.

To test hypothesis 4, we examined the relationships between abusive supervision and demographic variables, including supervisors’ age, subordinates’ age, tenure and time with their supervisor. As shown in Table 2, supervisors’ age \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.05} \right)\) is negatively related to abusive supervision but this correlation is not significant. On the employee side, only subordinates’ age \(\left( {\bar{r} = - 0.04} \right)\) is significantly related to abusive supervision. Consequently, hypothesis 4 is partially supported.

Moderation Effect of Subordinates’ Demographic Variables

Hypothesis 5 proposed that subordinates’ demographics (gender, organizational tenure, working time with supervisors, and age) would moderate the effects of the other antecedents. Random effects meta-regression was adopted to test these moderating effects. As shown in Table 3, interactional justice is a stronger negative predictor of abusive supervision for samples that have higher proportions of males. In contrast, supervisor EI is a stronger negative predictor of abusive supervision for largely female samples. Political skill has less of a negative impact for largely male samples.

Subordinates’ organizational tenure moderates the relationship between subordinates’ political skill and abusive supervision. Specifically, the negative effects of political skill are weaker for employees who have been employed with the organization for a long time.

Subordinates’ time with their supervisor moderates the effects of supervisor EI and gender dissimilarity. For employees who have spent a longer time with their supervisor, the negative association between supervisor EI and abusive supervision becomes stronger. In addition, gender dissimilarity becomes positively associated with abusive supervision.

Moderating Effects of Research Design

In hypothesis 6, we proposed that the correlations between antecedents and abusive supervision will be inflated by research designs involving same-source and same-time data collection. To test this hypothesis, subgroup analysis was conducted on aggressive norm, negative affectivity and unethical leadership. All three antecedents have shown heterogeneous effects on abusive supervision, as indicated by significant Q values in Table 2. We made comparisons between research designs where sufficient samples were available. The results presented in Table 4 indicate that the correlation between aggressive norm and abusive supervision does not differ significantly between same-source (employee rating) versus different-source data, as represented by overlapping 95 % credibility intervals between these two subgroups. The findings also indicate that time lag moderates the effects of negative affectivity and unethical leadership. Specifically, the effect of negative affectivity is stronger when it is measured at a different time to abusive supervision. Conversely, the effect of unethical leadership is weaker when measured at a different time. In summary, hypothesis 6 was partially supported, with evidence that time lag but not data source moderates the effect of each antecedent.

Discussion

Theoretical Implications and General Discussion

This meta-analysis provides not only a quantitative review of abusive supervision antecedents, but also outlines a systematic framework of these factors. This review is a response to the urgent need for a comprehensive analysis of the antecedents of abusive supervision. Several propositions which have not been tested before are examined. The relationships between abusive supervision and its antecedents are tested, including: supervisor-, organization- and subordinate-related variables, as well as demographic characteristics of supervisors and subordinates. In addition, moderators of these relationships are investigated. Most results confirm our hypotheses. Figure 2, which plots the absolute values of each weighted mean correlation against how many samples are included in about its correlation, summarizes our findings.Footnote 4

Summary of meta-analytic estimates for abusive supervision antecedents by number of samples. Filled circle supervisor’s state, filled square leadership style, filled triangle organizational climate, filled inverted triangle subordinate trait, filled diamond supervisor demographic variable, open circle subordinate demographic variable

For variables located in the left area (k < 5) of Fig. 2, it is hard to draw firm conclusions about their relationships with abusive supervision because of the relatively small numbers of samples. More specifically, variables in the lower left quadrant have weak relationships with abusive supervision \(\left( {\bar{r} < 0.20} \right)\). With the progress of the theory development and the increase in the number of empirical studies, the precision and consistency of these estimates will improve. Variables in upper left quadrant \(\left( {\bar{r} > 0.20} \right)\) have stronger relationships with abusive supervision. Most variables in this quadrant are related to supervisors’ affective state, although supervisor-related antecedents have been considered to be the most relevant antecedents of abusive supervision (Tepper 2007). This area may be promising for future study, given the relatively small number of extant studies yet relatively strong observed relationships. For variables located in the right area (k > 5) of Fig. 2, their relationships with abusive supervision have received more attention. Variables in the lower right quadrant have weak relationships with abusive supervision \(\left( {\bar{r} < 0.20} \right)\). Supervisors’ age is the only variable in this area. The result shows that the relationship between supervisors’ age and abusive supervision is not significantly different from zero, which suggest supervisors’ age does not influence their abusive behavior towards subordinates. Supervisors’ leadership styles are mainly located in the upper right quadrant. This indicates that there is fairly robust evidence for the relationship between supervisors’ leadership style and abusive supervision.

Despite the observed relationship between leadership style and abusive supervision, no solid theory has been proposed to explain their association. Most research treats abusive supervision and other leadership styles as different independent variables of other outcomes (Palanski et al. 2014; Yagil 2006), or uses abusive supervision as a variable to test the discriminant validity with other negative leadership styles (Brown et al. 2005; Camps et al. 2012). This situation may result from the fact that scholars have a tendency to treat abusive supervision as a kind of leadership, such as destructive leadership (Schyns and Schilling 2013). However, this treatment violates the original definition of abusive supervision, which emphasizes abusive supervision as subordinates’ perception of supervisors’ abusive behavior (Tepper 2000). Therefore, more theoretical work should be conducted to clarify the relationship between supervisors’ leadership and abusive supervision. Otherwise, the misleading conceptualization will guide the empirical research on abusive supervision to nowhere.

Limitations of the Study

This meta-analysis has at least two limitations. First, it is limited by the availability and quality of data from primary research. Most studies in this meta-analysis employ a cross-sectional research design; therefore, it is difficult to infer causal relationships. Moreover, studies that employ a same-time, same-source (mono-method) research design will suffer from common method variance (Podsakoff et al. 2003). In particular, our results indicate that negative affectivity, which is thought to inflate the effects of other variables (Watson et al. 1987), has a strong relationship with abusive supervision \(\left( {\bar{r} > 0.32} \right)\). This finding suggests that the relationships between abusive supervision and some antecedents are highly likely to be inflated in mono-method research. Second, the Q statistics suggest that there is large between-study heterogeneity, which indicates the existence of potential moderators. However, the limited amount of moderators in primary research constrains the number of comparisons that can be made. It is not possible to examine some moderators suggested by previous scholars, such as employees’ attribution bias and organizational structure (Martinko et al. 2013; Tepper 2007).

Future Research

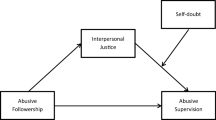

Given the argument by Tepper (2007, p. 285) that abusive supervision research is more phenomenon- than theory-driven, developing an integrative theoretical framework of abusive supervision is urgently required. In particular, research on antecedents of abusive supervision is in an early stage, and needs more theoretical guidance. Scholars who use theories of justice, displaced aggression and stress to study why supervisors are abusive have already made some progress. The next stage of this research stream can be extended to the study of mechanisms and boundary effects. “Organization-related antecedents” constitutes an absolutely new area for research; the results show that only two factors have been investigated. Other potential organization-related antecedents, like human resource practices, organizational culture, are worth examining. The investigation of organization-related antecedents will also involve multilevel issues, which have been proposed before (Ng et al. 2012; Tepper 2007). However, only a few studies have undertaken a multilevel perspective to study abusive supervision (e.g., Liu et al. 2012). As a multilevel phenomenon, abusive supervision needs more studies to move beyond individual level factors. “Subordinate-related antecedents” is probably the most promising area for future research in exploring the antecedents of abusive supervision. The previous abusive supervision literature takes a simple “giver and taker” perspective, indicating that the supervisor is the “giver” of abusive supervision and the subordinate is the “taker” or receiver (Martinko et al. 2013). Based on this logic, research on antecedents of abusive supervision focuses on the supervisor, such as supervisors’ state and traits. In contrast, research on the consequences of abusive supervision focuses on subordinates, such as subordinates’ wellbeing and performance. However, scholars have already realized that this ‘logic’ has misled the research direction of abusive supervision. In the latest reviews on abusive supervision, Martinko et al. (2013) proposed a reversed model, arguing that subordinates’ working behavior is the cause of abusive supervision, rather than simply being the consequences. Based on the scope of justice theory, Tepper et al. (2011) provide empirical support for this model. Future research that examines the victim’s role in workplace aggression may be fruitful (Aquino and Thau 2009).

This meta-analysis should be considered preliminary, given the relatively nascent state of research on the antecedents of abusive supervision. It also does not include some important antecedents, such as supervisors’ aggression history, due to the limited number of available samples. However, this meta-analysis provides invaluable insights into the antecedents of abusive supervision based on all of the available information to date. Similar to Lowe et al. (1996) early meta-analysis on transformational leadership, our review provides a strong basis for a future research agenda. Research on the antecedents of abusive supervision can build on this meta-analysis by further investigating areas that have been under-researched. Future systematic reviews can integrate the results from this and other meta-analyses, such as Schyns and Schilling (2013) review of the consequences of destructive leadership, to investigate potential mediators using meta-path analysis (Landis 2013).

Practical Implications

Because of the destructive consequences of abusive supervision, it is urgent to determine its antecedents (Ng and Chen 2012). Our research summarizes different sources of abusive supervision. A more sanguine implication is that it may be possible to reduce the occurrence of abusive supervision if senior managers in organizations can implement relevant policies based on the results of this study. Organizations should build systematic training systems for supervisors to shape their leadership; they need to be made aware that their behavior has a strong impact on subordinates’ wellbeing and perceptions of their leadership style (Aryee et al. 2007). For an organization, promoting a culture of fairness will benefit both supervisors and subordinates. Supervisors will experience less unjust treatment and subordinates will perceive less abusive supervision because a fairness culture decreases the possibility that an aggressive norm will be formed in an organization (Restubog et al. 2011). Most subordinate-related antecedents are personal traits, which stabilize over time. Human resource management departments in organizations may need to consider individual characteristics as a selection criterion for recruitment (Tepper et al. 2011).

Conclusion

In summary, this meta-analysis examined the relationships between abusive supervision and its antecedents. Generally, the quantitative results support our hypotheses that the four proffered antecedent categories are significantly related to abusive supervision. In terms of its major contributions, this meta-analysis highlights the importance of a range of antecedents of abusive supervision. It proposes an organizing framework for categorizing these antecedents, and it tests the effects of several moderators. Finally, our review points to areas that have been under-studied, and recommends ways in which abusive supervision research may be advanced. Ultimately, our meta-analysis provides insights by which organizations may address the issue of abusive supervision and the destructive consequences that occur in its wake.

Notes

Schyns and Schilling (2013) conducted a meta-analysis on destructive leadership, which contains abusive supervision as one type of destructive leadership.

A summary of studies and sample characteristics can be provided by the corresponding author upon request.

One coder is the author of this paper. The other coder is an expert in organizational behavior researcher who has sufficient knowledge of abusive supervision.

Five demographic variables in Fig. 2 are excluded because they are normally considered as control variables in the extant literature.

References

Aquino, K., & Thau, S. (2009). Workplace victimization: Aggression from the target’s perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 717–741.

Bamberger, P. A., & Bacharach, S. B. (2006). Abusive supervision and subordinate problem drinking: Taking resistance, stress and subordinate personality into account. Human Relations, 59(6), 723–752.

Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall PTR.

Barling, J., Dupre, K. E., & Kelloway, E. K. (2009). Predicting workplace aggression and violence. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 671–692.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2011). Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Bowling, N. A., & Beehr, T. A. (2006). Workplace harassment from the victim’s perspective: A theoretical model and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 998–1012.

Colbert, A. E., Judge, T. A., Choi, D., & Wang, G. (2012). Assessing the trait theory of leadership using self and observer ratings of personality: The mediating role of contributions to group success. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(4), 670–685.

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O. L. H., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 425.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Rodell, J. B., Long, D. M., Zapata, C. P., Conlon, D. E., & Wesson, M. J. (2013). Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 199–236.

Conger, J. A. (1998). Qualitative research as the cornerstone methodology for understanding leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 9(1), 107–121.

Conway, N., & Coyle-Shapiro, J. A. M. (2012). The reciprocal relationship between psychological contract fulfilment and employee performance and the moderating role of perceived organizational support and tenure. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 85(2), 277–299.

Dekker, I., & Barling, J. (1998). Personal and organizational predictors of workplace sexual harassment of women by men. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3(1), 7–18.

DeRue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., Wellman, N., & Humphrey, S. E. (2011). Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: An integration and meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 7–52.

Felson, R. B. (1992). Kick’em when they’re down. The Sociological Quarterly, 33(1), 1–16.

Ferris, G. R., Davidson, S. L., & Perrewe, P. L. (2010). Political skill at work: Impact on work effectiveness. Boston: Nicholas Brealey.

Gerstner, C. R., & Day, D. V. (1997). Meta-analytic review of leader–member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 827–844.

Grandy, G., & Starratt, A. (2010). Making sense of abusive leadership the experiences of young workers. Charlotte, NC: Information Age-IAP.

Gross, J. J., Carstensen, L. L., Pasupathi, M., Tsai, J., Skorpen, C. G., & Hsu, A. Y. C. (1997). Emotion and aging: Experience, expression, and control. Psychology and Aging, 12(4), 590–599.

Harrell-Cook, G., Ferris, G. R., & Dulebohn, J. H. (1999). Political behaviors as moderators of the perceptions of organizational politics–work outcomes relationships. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20(7), 1093–1105.

Harris, K. J., Kacmar, K. M., & Boonthanum, R. (2005) The interrelationship between abusive supervision, leader–member exchange, and various outcomes. Paper presented at Annual Meeting of the Society for Industrial–Organizational Psychology, Los Angeles, CA.

Harris, K. J., Kacmar, K. M., & Zivnuska, S. (2007). An investigation of abusive supervision as a predictor of performance and the meaning of work as a moderator of the relationship. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 252–263.

Harvey, P., Stoner, J., Hochwarter, W., & Kacmar, C. (2007). Coping with abusive supervision: The neutralizing effects of ingratiation and positive affect on negative employee outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 264–280.

Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. B. (2005). What we know about leadership. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 169–180.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (2004). Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Johnson, H. A. M., & Spector, P. E. (2007). Service with a smile: Do emotional intelligence, gender, and autonomy moderate the emotional labor process? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(4), 319–333.

Landis, R. S. (2013). Successfully combining meta-analysis and structural equation modeling: Recommendations and strategies. Journal of Business and Psychology, 28(3), 251–261.

Lowe, Kevin B., Kroeck, K. Galen, & Sivasubramaniam, Nagaraj. (1996). Effectiveness correlates of transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic review of the MLQ literature. The Leadership Quarterly, 7(3), 385–425.

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., Brees, J. R., & Mackey, J. (2013). A review of abusive supervision research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(S1), S120–S137.

Ng, S. B. C., & Chen, G. Z. X. (2012). Abusive supervision, silence climate and silence behaviors: A multi-level examination of the mediating processes in China. Paper presented at the Iternational Association for Chinese Management Research (IACMR) conference, Hongkong.

Ng, S. B. C., Chen, Z. X., & Aryee, S. (2012). Abusive supervision in Chinese work settings. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175.

Olafsson, R. F., & Johannsdottir, H. L. (2004). Coping with bullying in the workplace: The effect of gender, age and type of bullying. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 32(3), 319–333.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Jeong-Yeon, L., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879.

Richardson, H. A., Simmering, M. J., & Sturman, M. C. (2009). A tale of three perspectives examining post hoc statistical techniques for detection and correction of common method variance. Organizational Research Methods, 12(4), 762–800.

Rothstein, H. R., & Hopewell, S. (2009). Grey literature. In H. Cooper, L. V. Hedges, & J. C. Valentine (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (pp. 103–125). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Schat, A. C., Frone, M. R., & Kelloway, E. K. (2006). Prevalence of workplace aggression in the US workforce: Findings from a national study. In E. K. Kelloway, J. Barling, & J. J. Hurrell Jr. (Eds.), Handbook of workplace violence (pp. 47–90). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schyns, B., & Schilling, J. (2013). How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 138–158.

Smith, P. K., Shu, S., & Madsen, K. (2001). Characteristics of victims of school bullying: developmental changes in coping strategies and skills. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment at school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimised (pp. 332–352). New York: Guildford.

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190.

Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33(3), 261–289.

Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., & Shaw, J. D. (2001). Personality moderators of the relationship between abusive supervision and subordinates’ resistance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 974–983.

Tepper, B. J., Moss, S. E., Lockhart, D. E., & Carr, J. C. (2007). Abusive supervision, upward maintenance communication, and subordinates’ psychological distress. Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), 1169–1180.

Watson, D., Pennebaker, J. W., & Folger, R. (1987). Beyond negative affectivity: Measuring stress and satisfaction in the workplace. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 8(2), 141–158.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1994). An alternative approach to method effects by using latent-variable models: Applications in organizational-behavior research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(3), 323–331.

Wong, C.-S., & Law, K. S. (2002). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(3), 243–274.

Wu, L. Z., Kwan, H. K., Liu, J., & Resick, C. J. (2012). Work-to-family spillover effects of abusive supervision. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(7), 714–731.

Yukl, G. A. (2006). Leadership in organizations. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson–Prentice Hall.

References: studies included in the meta-analysis.

Alexander, K. (2012). Abusive supervision as a predictor of deviance and health outcomes: The exacerbating role of narcissism and social support. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 72(12-B), 7731.

Aryee, S., Chen, Z. X., Sun, L. Y., & Debrah, Y. A. (2007). Antecedents and outcomes of abusive supervision: Test of a trickle-down model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 191–201.

Aryee, S., Sun, L. Y., Chen, Z. X. G., & Debrah, Y. A. (2008). Abusive supervision and contextual performance: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion and the moderating role of work unit structure. Management and Organization Review, 4(3), 393–411.

Bardes, M. (2009). Aspects of goals and rewards systems as antecedents of abusive supervision: The mediating effect of hindrance stress. Florida, USA: University of Central Florida.

Biron, M. (2010). Negative reciprocity and the association between perceived organizational ethical values and organizational deviance. Human Relations, 63(6), 875–897.

Bowling, N. A., & Michel, J. S. (2011). Why do you treat me badly? The role of attributions regarding the cause of abuse in subordinates’ responses to abusive supervision. Work and Stress, 25(4), 309–320.

Breaux, D. M., Perrewé, P. L., Hall, A. T., Frink, D. D., & Hochwarter, W. A. (2008). Time to try a little tenderness? The detrimental effects of accountability when coupled with abusive supervision. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 15(2), 111–122. (Sage).

Brown, M. E., Trevino, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Burris, E. R., Detert, J. R., & Chiaburu, D. S. (2008). Quitting before leaving: The mediating effects of psychological attachment and detachment on voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4), 912–922.

Burton, J. P., & Hoobler, J. M. (2011). Aggressive reactions to abusive supervision: The role of interactional justice and narcissism. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 52(4), 389–398.

Burton, J. P., Hoobler, J. M., & Scheuer, M. L. (2012). Supervisor workplace stress and abusive supervision: The buffering effect of exercise. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(3), 271–279.

Camps, J., Decoster, S., & Stouten, J. (2012). My share is fair, so i don’t care the moderating role of distributive justice in the perception of leaders’ self-serving behavior. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 11(1), 49–59.

Carlson, D., Ferguson, M., Hunter, E., & Whitten, D. (2012). Abusive supervision and work–family conflict: The path through emotional labor and burnout. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(5), 849–859.

Chi, S.-C. S., & Liang, S.-G. (2013). When do subordinates’ emotion-regulation strategies matter? Abusive supervision, subordinates’ emotional exhaustion, and work withdrawal. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 125.

Decoster, S., Camps, J., Stouten, J., Vandevyvere, L., & Tripp, T. M. (2013). Standing by your organization: The impact of organizational identification and abusive supervision on followers’ perceived cohesion and tendency to gossip. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(3), 623–634.

Detert, J. R., Trevino, L. K., Burris, E. R., & Andiappan, M. (2007). Managerial modes of influence and counterproductivity in organizations: A longitudinal business-unit-level investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 993–1005.

Ding, X. Q., Tian, K., Yang, C. S., & Gong, S. F. (2012). Abusive supervision and LMX: Leaders’ emotional intelligence as antecedent variable and trust as consequence variable. Chinese Management Studies, 6(2), 258–271.

Duffy, M. K., & Ferrier, W. J. (2003). Birds of a feather…? How supervisor-subordinate dissimilarity moderates the influence of supervisor behaviors on workplace attitudes. Group and Organization Management, 28(2), 217–248.

Dupre, K. E. (2005). Beating up the boss: The prediction and prevention of interpersonal aggression targeting workplace supervisors. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 63(3-A), 669.

Dupre, K. E., Inness, M., Connelly, C. E., Barling, J., & Hoption, C. (2006). Workplace aggression in teenage part-time employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 987–997.

Haggard, D. L., Robert, C., & Rose, A. J. (2011). Co-rumination in the workplace: Adjustment trade-offs for men and women who engage in excessive discussions of workplace problems. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(1), 27–40.

Harris, K. J., Harvey, P., & Kacmar, K. M. (2011). Abusive supervisory reactions to coworker relationship conflict. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(5), 1010–1023.

Harris, K. J., Harvey, P., Harris, R. B., & Cast, M. (2013). An investigation of abusive supervision, vicarious abusive supervision, and their joint impacts. Journal of Social Psychology, 153(1), 38–50.

Hobman, E. V., Restubog, S. L. D., Bordia, P., & Tang, R. L. (2009). Abusive supervision in advising relationships: Investigating the role of social support. Applied Psychology—an International Review (Psychologie Appliquee—Revue Internationale), 58(2), 233–256.

Hoobler, J. M., & Brass, D. J. (2006). Abusive supervision and family undermining as displaced aggression. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1125–1133.

Hoobler, J. M., & Hu, J. (2013). A model of injustice, abusive supervision, and negative affect. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 256–269.

Inness, M., Barling, J., & Tumer, N. (2005). Understanding supervisor-targeted aggression: A within-person, between-jobs design. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 731–739.

Jian, Z. Q., Kwan, H. K., Qiu, Q., Liu, Z. Q., & Yim, F. H. K. (2012). Abusive supervision and frontline employees’ service performance. Service Industries Journal, 32(5), 683–698.

Kernan, M. C., Watson, S., Chen, F. F., & Kim, T. G. (2011). How cultural values affect the impact of abusive supervision on worker attitudes. Cross Cultural Management—an International Journal, 18(4), 464–484.

Kiazad, K., Restubog, S. L. D., Zagenczyk, T. J., Kiewitz, C., & Tang, R. L. (2010). In pursuit of power: The role of authoritarian leadership in the relationship between supervisors’ machiavellianism and subordinates’ perceptions of abusive supervisory behavior. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(4), 512–519.

Kiewitz, C., Restubog, S. L. D., Zagenczyk, T. J., Scott, K. D., Garcia, P., & Tang, R. L. (2012). Sins of the parents: Self-control as a buffer between supervisors’ previous experience of family undermining and subordinates’ perceptions of abusive supervision. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(5), 869–882.

Lian, H. W., Ferris, D. L., & Brown, D. J. (2012a). Does power distance exacerbate or mitigate the effects of abusive supervision? It depends on the outcome. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 107–123.

Lian, H. W., Ferris, D. L., & Brown, D. J. (2012b). Does taking the good with the bad make things worse? How abusive supervision and leader-member exchange interact to impact need satisfaction and organizational deviance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 117(1), 41–52.

Lian, H., Brown, D., Ferris, D. L., Liang, L., Keeping, L., & Morrison, R. (2013). Abusive supervision and retaliation: A self-control framework. Academy of Management Journal, 57, 116–139.

Lin, W. P., Wang, L., & Chen, S. T. (2013). Abusive supervision and employee well-being: The moderating effect of power distance orientation. Applied Psychology—an International Review (Psychologie Appliquee—Revue Internationale), 62(2), 308–329.

Liu, J., Kwan, H. K., Wu, L. Z., & Wu, W. K. (2010). Abusive supervision and subordinate supervisor-directed deviance: The moderating role of traditional values and the mediating role of revenge cognitions. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 835–856.

Liu, D., Liao, H., & Loi, R. (2012). The dark side of leadership: A three-level investigation of the cascading effect of abusive supervision on employee creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1187–1212.

Liu, C., Yang, L. Q., & Nauta, M. M. (2013). Examining the mediating effect of supervisor conflict on procedural injustice–job strain relations: The function of power distance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(1), 64–74.

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., Sikora, D., & Douglas, S. C. (2011). Perceptions of abusive supervision: The role of subordinates’ attribution styles. Leadership Quarterly, 22(4), 751–764.

Mawritz, M. B., Mayer, D. M., Hoobler, J. M., Wayne, S. J., & Marinova, S. V. (2012). A trickle-down model of abusive supervision. Personnel Psychology, 65(2), 325–357.

Mayer, D. M., Thau, S., Workman, K. M., Van Dijke, M., & De Cremer, D. (2012). Leader mistreatment, employee hostility, and deviant behaviors: Integrating self-uncertainty and thwarted needs perspectives on deviance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 117(1), 24–40.

Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2007). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1159–1168.

Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2012). Employees’ behavioral reactions to supervisor aggression: An examination of individual and situational factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(6), 1148–1170.

Nelson, R. J. (1998). Abusive supervision and subordinates’ coping strategies (p. 88). Kentucky, USA: University of Kentucky.

Ogunfowora, B. (2009). The consequences of ethical leadership: Comparisons with transformational leadership and abusive supervision. Calgary, Canada: University of Calgary.

Palanski, M., Avey, J. B., & Jiraporn, N. (2014). The effects of ethical leadership and abusive supervision on job search behaviors in the turnover process. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(1), 135–146.

Pyc, L. S. (2012). The moderating effects of workplace ambiguity and perceived job control on the relations between abusive supervision and employees’ behavioral, psychological, and physical strains. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 72(8-A), 2986.

Rafferty, A. E., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2011). The influence of abusive supervisors on followers’ organizational citizenship behaviours: The hidden costs of abusive supervision. British Journal of Management, 22(2), 270–285.

Rafferty, A. E., Restubog, S. L. D., & Jimmieson, N. L. (2010). Losing sleep: Examining the cascading effects of supervisors’ experience of injustice on subordinates’ psychological health. Work and Stress, 24(1), 36–55.

Restubog, S. L. D., Scott, K. L., & Zagenczyk, T. J. (2011). When distress hits home: The role of contextual factors and psychological distress in predicting employees’ responses to abusive supervision. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 713–729.

Shao, P., Resick, C. J., & Hargis, M. B. (2011). Helping and harming others in the workplace: The roles of personal values and abusive supervision. Human Relations, 64(8), 1051–1078.

Shoss, M. K., Eisenberger, R., Restubog, S. L. D., & Zagenczyk, T. J. (2013). Blaming the organization for abusive supervision: The roles of perceived organizational support and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 158–168.

Sulea, C., Filipescu, R., Horga, A., Ortan, C., & Fischmann, G. (2012). Interpersonal mistreatment at work and burnout among teachers. Cognition, Brain, Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 16(4), 553–570.

Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., Hoobler, J., & Ensley, M. D. (2004). Moderators of the relationships between coworkers’ organizational citizenship behavior and fellow employees’ attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 455–465.

Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., Henle, C. A., & Lambert, L. S. (2006). Procedural injustice, victim precipitation, and abusive supervision. Personnel Psychology, 59(1), 101–123.

Tepper, B. J., Lambert, L. S., Henle, C. A., Giacalone, R. A., & Duffy, M. K. (2008). Abusive supervision and subordinates’ organization deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4), 721–732.

Tepper, B. J., Carr, J. C., Breaux, D. M., Geider, S., Hu, C. Y., & Hua, W. (2009). Abusive supervision, intentions to quit, and employees’ workplace deviance: A power/dependence analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109(2), 156–167.

Tepper, B. J., Moss, S. E., & Duffy, M. K. (2011). Predictors of abusive supervision: Supervisor perceptions of deep-level dissimilarity, relationship conflict, and subordinate performance. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 279–294.

Thau, S., & Mitchell, M. S. (2010). Self-gain or self-regulation impairment? Tests of competing explanations of the supervisor abuse and employee deviance relationship through perceptions of distributive justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(6), 1009–1031.

Thau, S., Bennett, R. J., Mitchell, M. S., & Marrs, M. B. (2009). How management style moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and workplace deviance: An uncertainty management theory perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(1), 79–92.

Thoroughgood, C. N., Tate, B. W., Sawyer, K. B., & Jacobs, R. (2012). Bad to the bone: Empirically defining and measuring destructive leader behavior. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 19(2), 230–255.

Thun, B., & Kelloway, E. K. (2011). Virtuous leaders: Assessing character strengths in the workplace. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences (Revue Canadienne Des Sciences De L Administration), 28(3), 270–283.

Wang, W., Mao, J. Y., Wu, W. K., & Liu, J. (2012). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance: The mediating role of interactional justice and the moderating role of power distance. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 50(1), 43–60.

Whitman, M. V., Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Shanine, K. K. (2013). Psychological entitlement and abusive supervision: Political skill as a self-regulatory mechanism. Health Care Management Review, 38(3), 248–257.

Whitman, M. V., Halbeslebe, J. R. B., & Holmes, O. (2014). Abusive supervision and feedback avoidance: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(1), 38–53.

Wu, T.-Y. (2008). Abusive supervision and emotional exhaustion: The mediating effects of subordinate justice perception and emotional labor. Chinese Journal of Psychology, 50(2), 201–221.

Wu, T. Y., & Hu, C. Y. (2009). Abusive supervision and employee emotional exhaustion dispositional antecedents and boundaries. Group and Organization Management, 34(2), 143–169.

Wu, L.-Z., Liu, J., & Liu, G. (2009). Abusive supervision and employee performance: Mechanisms of traditionality and trust. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 41(6), 510–518.

*Wu, W. K., Wang, W. & Liu, J. (2010) Abusive supervision and team effectiveness: The mediating role of team efficacy. Paper presented at 2010 IEEE International Conference on Management Science and Engineering.

Xu, E., Huang, X., Lam, C. K., & Miao, Q. (2012). Abusive supervision and work behaviors: The mediating role of LMX. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(4), 531–543.

Yagil, D. (2006). The relationship of abusive and supportive workplace supervision to employee burnout and upward influence tactics. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 6(1), 49–65.

Yagil, D., Ben-Zur, H., & Tamir, I. (2011). Do employees cope effectively with abusive supervision at work? An exploratory study. International Journal of Stress Management, 18(1), 5–23.

Zellars, K. L., Tepper, B. J., & Duffy, M. K. (2002). Abusive supervision and subordinates’ organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(6), 1068–1076.

Zhao, H. D., Peng, Z. L., Han, Y., Sheard, G., & Hudson, A. (2013). Psychological mechanism linking abusive supervision and compulsory citizenship behavior: A moderated mediation study. Journal of Psychology, 147(2), 177–195.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Yumeng Yue for research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Bednall, T.C. Antecedents of Abusive Supervision: a Meta-analytic Review. J Bus Ethics 139, 455–471 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2657-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2657-6