Abstract

Previous research has shed light on the detrimental effects of abusive supervision. To extend this area of research, we draw upon conservation of resources theory to propose (a) a causal relationship between abusive supervision and psychological distress, (b) a mediating role of psychological distress on the relationship between abusive supervision and employee silence, and (c) a moderating effect of the supervisor–subordinate relational context (i.e., gender dissimilarity) on the mediating effect of abusive supervision on silence. Through an experimental study (Study 1), we found the causal path linking abusive supervision and psychological distress. Results of both the experimental study and a field study (Study 2) provided evidence that psychological distress mediated the relationship between abusive supervision and silence. Lastly, we found support that this mediation effect was contingent upon the relational context in Study 2 but not in Study 1. We discuss implications for theory and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A growing interest has been observed in deviant or counterproductive behaviors in the workplace (Ferris et al. 2016; Palanski et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2014; Avey et al. 2014). As a result, research on abusive supervision or the “dark side” of leadership has emerged, a topic that emphasizes its detrimental effects on employees (Martinko et al. 2013; Tepper 2007). Abusive supervision is defined as the subordinates’ perceptions of “the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact” from their supervisors (Tepper 2000, p. 178).

Extant research has established that abusive supervision is negatively related to employee outcomes, such as job satisfaction, psychological wellbeing, and citizenship behaviors (Restubog et al. 2011; Tepper 2000; Aryee et al. 2007), and positively associated with feedback avoidance and deviant behaviors toward supervisors (Thau et al. 2009; Whitman et al. 2014). However, inferring the causal relationships implied by these studies may be limiting due to the lack of experimental and/or longitudinal designs (Mackey et al. 2015; Martinko et al. 2013). In particular, researchers have found a relationship between abusive supervision and psychological distress, with the latter being defined as negative mental states that are characterized by negative thoughts and feelings related to anxiety, fear, or depression (e.g., Restubog et al. 2011; Tepper 2000). Given the possibility that distressed employees may provoke abusive supervision, the direction of this causal relationship needs to be substantiated (Restubog et al. 2011). Thus, the first goal of our study is to examine the causal relationship between abusive supervision and psychological distress through scenario-based experiments.

To understand the underlying mechanisms by which abusive supervision affects subordinate outcomes, studies have drawn upon social exchange theory and justice theory to examine potential mediators, such as ego depletion (e.g., Thau and Mitchell 2010) and interactional justice (e.g., Aryee et al. 2007). Recently, research based on conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll and Shirom 2001; Hobfoll 1989) highlighted the stress process of abusive supervision by examining the mediating role of psychological strain in the form of emotional exhaustion (e.g., Whitman et al. 2014; Xu et al. 2015). COR theory posits that stress is activated by a threat and/or actual loss of valued resources, and that individuals are motivated to protect and retain their limited resources (Hobfoll 1989). Considering abusive supervision as a workplace stressor, Whitman et al. suggested that abusiveness may deplete subordinates’ cognitive resources, which leads to their coping strategy (i.e., avoidant behaviors) in an attempt to conserve their remaining resources. To continue this research stream, we use COR as our overarching theory and argue that supervisor abusiveness depletes the resources of subordinates; thus, subordinates experience detrimental psychological consequences and tend to remain silent as a coping mechanism (cf. Xu et al. 2015). Silence refers to the withholding of potentially important input that may improve procedures and outcomes in the workplace (Morrison 2011). The second goal of our study is to determine if psychological distress is a potential mechanism that can explain the effect of abusive supervision on silence.

Abusive supervision may not uniformly affect all employees (Tepper 2007), and researchers have examined the potential moderating factors that change the magnitude of such an effect (e.g., Restubog et al. 2011). Although the negative relationship between abusive supervision and job performance has been found to be weaker among employees with high conscientiousness (Nandkeolyar et al. 2014), employees reporting high meaning in their work (i.e., the degree to which employees value the work they do) perform poorly when they experience abusive supervision (Harris et al. 2007). Nevertheless, little convergence seems to exist among the examined moderating effects (Tepper 2007), and additional research is required to empirically examine the role of contextual factors in buffering or exacerbating the effects of abusive supervision (cf. Chan and McAllister 2014). As the third goal of our study, we hope to add to this line of research by focusing on the moderating role of the relational context within which the supervisor and subordinate interact.

According to social identity theory (Ashforth et al. 2008; Tajfel and Turner 1986), individuals categorize others, with whom they interact, in socially salient ways. Whereas stronger identification occurs when similarities are perceived, dissimilarities mitigate the development of strong social identity ties (van Knippenberg and Hogg 2003). Given our focus on the relational context comprising supervisors and their subordinates within the work environment of our study, the gender composition of the supervisor and subordinate dyad is a salient aspect (e.g., Avery et al. 2013). Gender is an easily detected demographic attribute, and frequently the basis on which individuals categorize each other as being similar or dissimilar (i.e., gender dissimilarity) in a social context (Riordan and Shore 1997). Subordinates tend to identify less with their gender-dissimilar supervisors, feel psychological threats to their gender-based identities, and experience anxiety when interacting with supervisors (cf., Avery et al. 2013; Carter et al. 2014). According to COR theory, all these reactions signify that the cognitive resources of subordinates are threatened (Hobfoll 1989). These feelings reinforce the subordinates’ tendencies to anticipate mistreatment in future interactions with their dissimilar supervisors (Johnson et al. 2006). Because such a relational context (i.e., gender dissimilarity) inherently poses a threat to the social (i.e., identity, status) and psychological (i.e., supervisor support) resources (Hobfoll 1989), dissimilar subordinates, compared to gender-similar subordinates, are more likely to accept, or react less intensely to, mistreatment (i.e., abusive supervision) as anticipated. This suggests that the effect of abusive supervision on psychological distress and silent behavior tends to be less severe among subordinates with gender-dissimilar supervisors. As such, we posit that it is not gender per se (e.g., Restubog et al. 2011) but its confluence with the demographic difference from the supervisor (Tsui and O’Reilly 1989) that influences subordinates’ reactions to abusive supervision.

Our study contributes to the abusive supervision and silence research by examining why and under what circumstances such a supervisory behavior affects subordinates’ silent behavior in the workplace (cf. Xu et al. 2015). First, our research is one of the rare studies that attempt to establish causal relationships between abusive supervision and outcomes (e.g., Farh and Chen 2014). In a recent review, Martinko et al. (2013) contended that researchers assume that abusive supervision perceptions are valid proxies for actual supervisory behaviors, and that the causal inferences of abusive supervision and outcomes appear “unjustified” (p. 131). Mackey et al. (2015) also recommend that future studies should investigate the “issue of causality” (p. 17). Accordingly, we responded to these calls (Restubog et al. 2011) by conducting an experimental study to examine the causal effect of such a negative supervisory behavior on psychological distress. Second, to assess the extent of the psychological impact of abusive supervision, we investigated its subsequent behavioral implication, namely employee silence, through both experimental and field study samples. We thus explored the potential process by which abused employees tend to remain silent in the workplace. Third, we identified the potential moderating effects of the supervisor–subordinate relational context. Given that studies have suggested the moderating role of relational demographics on work outcomes (Avery et al. 2013; Carter et al. 2014), we propose that supervisor–subordinate demographic differences (i.e., gender dissimilarity) influence subordinates’ reactions to their supervisors’ abuses. Fourth, our study contributes to the employee silence research by investigating the antecedents and relational contextual factors of silence. Although employee silence is not only common but also highly dysfunctional in the workplace, examining how and why employees remain silent has only emerged recently; thus, additional studies are required to broaden our understanding of such a phenomenon (Morrison 2014; Morrison et al. 2015). Overall, we responded to the call for examining the mediating and moderating effects of abusive supervision on outcomes (Restubog et al. 2011).

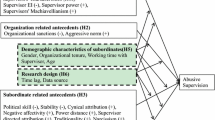

We tested our proposed model using samples from China and South Korea, which are characterized by the Confucian Asian culture (Hofstede 2001). Originally conducted in the United States (Tepper 2000), abusive supervision research has recently utilized non-US samples from China (e.g., Farh and Chen 2014; Lin et al. 2013; Xu et al. 2015), Korea (e.g., Kim et al. 2015; Kim and Yun 2015; Lee et al. 2013), and other countries (e.g., Philippines—Restubog et al. 2011), and found consistent findings with those using the US samples (Martinko et al. 2013). To the extent that our research questions receive empirical support, we anticipate that our proposed model would be applicable to the Western context. Figure 1 depicts our proposed study model.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Abusive Supervision and Psychological Distress

Researchers have used COR theory to understand the relationship between stressors and strains (Halbesleben et al. 2014). COR theory postulates that individuals are motivated to obtain and retain resources, and strive to prevent further loss of resources (Hobfoll 1989). Resources refer to things that individuals value, such as objects, conditions, status, or energies (Hobfoll and Shirom 2001). This theory suggests that resource loss affects employees more saliently than resource gain in the workplace, and that employees with fewer resources may be more vulnerable to stressors compared to those with extra resources (Hobfoll and Shirom 2001).

Being ridiculed or lied to by supervisors is a stressful workplace event (e.g., Whitman et al. 2014; Xu et al. 2015) that negatively affects employees’ wellbeing (Spector and Jex 1998). As a stressor, abusive supervision tends to deplete the employees’ resources. These resources may alleviate the employees’ psychological strain in the forms of anxiety, fear, and depression. When employees experience stressful or traumatic events, such as high levels of supervisory abuses, they tend to develop a negative mental state that is a manifestation of psychological distress.

Workplace harassment from supervisors can be considered as an extreme social stressor that may lead to chronic cognitive and physical activation (Nielsen and Einarsen 2012; Ursin and Eriksen 2004). A stress stimulus, such as abusive supervision, may be evaluated cognitively as a threatening situation, and if so would lead to a stress response which in turn activates cognitive arousal. Feedback loops occur as the individual re-evaluates the stimulus and experiences the stress response. High levels of cognitive arousal can be expected when one expects negative outcomes caused by an abusive supervisor. We suggest that this sustained activation leads to the depletion of resources. Individuals with fewer resources become vulnerable to a chronic stressful situation; and they may feel a high level of anxiety, fear, and depression (Restubog et al. 2011). Existing research supports the argument that subordinates experiencing abuse from their supervisors report higher levels of psychological distress (e.g., Restubog et al. 2011; Tepper 2000; Tepper et al. 2007). Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 1

Abusive supervision will be positively related to psychological distress.

Psychological Distress as a Mediator Between Abusive Supervision and Silence

Voice is important to organizations because it promotes new ideas and improvement. As a form of extra-role behavior, voice behavior, an expression of constructive suggestions intended for organizational improvement, shows positive association with outcomes, such as in‐role performance, creativity, and implementation of new ideas (Ng and Feldman 2012). Given the negative effect of abusive supervision, the current study is particularly interested in silence, an opposite to voice that “is failure to voice” (Morrison 2011, p. 380). Silence is harmful to organizations in that it may deter organizational learning, error correction, and crisis prevention (Morrison 2014).

COR theory provides an explanation for the underlying mechanism of psychological distress on the abusive supervision and silence relationship (Ng and Feldman 2012; Xu et al. 2015). As previously discussed, activating continual cognitive arousal may deplete resources and result in negative emotional states, such as psychological distress or emotional exhaustion. Stressed individuals may want to preserve their remaining resources by avoiding actions (i.e., voice) that may consume their already reduced resources. Because utilizing voice may include proposing changes in existing procedures and can be seen as an expression of dissatisfaction with the current situation, subordinates may deliberately consider the potential costs and benefits and therefore choose to be silent (Kish-Gephart et al. 2009).

Moreover, to prevent any further spiraling loss of resources, COR theory suggested that psychologically stressed individuals are motivated to adopt a passive coping mechanism (i.e., silence) that may help them avoid facing the abusers. Ng and Feldman (2012) suggested that when individuals are under stressful situations, they tend to withhold their ideas to prevent the depletion of resources. Xu et al. (2015) provided evidence that abused employees experience emotional exhaustion, which increases their tendency to remain silent. Following this line of reasoning, we propose that subordinates facing abusive supervision may experience continual cognitive arousal that depletes their resources and engenders distress which, in turn, leads to their silence.

Hypothesis 2

Psychological distress will mediate the relationship between abusive supervision and silence.

Supervisor and Subordinate Gender Dissimilarity as a Moderator

Social identity theory suggests that individuals seek to maintain a positive social identity through self-categorization processes based on the salient demographic characteristics (Ashforth et al. 2008; Tajfel and Turner 1986). As an easily observed characteristic, gender is frequently the basis on which individuals evaluate similarity/dissimilarity in a relational context in the workplace (Riordan and Shore 1997; Tsui and O’Reilly 1989) and is relevant to personal identity (McCann et al. 1985). Similar individuals are connected by their shared gender identity and form an in-group, but view gender-dissimilar others as out-group members. Expectancies (or stereotypes in some cases) regarding others’ prospective attitudes or behaviors can be generated from this categorization process (Carter et al. 2014).

Gender similarity signals in-group membership status and positive social identity, both of which are valuable resources (Hobfoll 1989). To subordinates, these resources are significant in that they help define who they are in their work environment (Hobfoll 1989). Gender-similar subordinates naturally expect to receive favorable treatment, such as a disproportionate amount of attention, information, and support from their supervisors. For example, subordinates tend to receive higher levels of support from their gender-similar supervisors than those with gender-different supervisors (Foley et al. 2006). In the abusive treatment situation, such supervisory behaviors signal that subordinates are less respected members despite their similar gender attribute with the supervisor. This violation of expectation poses a substantial threat to these subordinates’ identity (Schaubroeck et al. 2016). Such a threat is symbolic because the abuses cast doubt on these subordinates’ positive identity beliefs and threaten their membership status (Hobfoll 1989). As a result, gender-similar subordinates experience high levels of resource losses that trigger psychological distress, thereby creating a tendency to withhold their input and suggestions as a means of avoiding further loss of resources.

Conversely, gender dissimilarity may evoke negative social categorization processes that individuals perceive as psychological threats to their gender-based identity and cues to their out-group membership status in the workplace (e.g., Avery et al. 2013), both of which indicate a threat to resources (Hobfoll 1989). Dissimilar subordinates may sense neglect or even exclusion by their supervisors (cf. Avery et al. 2013), and develop stereotypical inferences regarding supervisory behaviors (cf. Carter et al. 2014). For example, female subordinates with male supervisors are more likely to perceive sex-based discrimination than their male counterparts with same gender supervisors (Avery et al. 2013). Such negative feelings and stereotyping reinforce dissimilar subordinates’ inclinations to anticipate mistreatment when interacting with their supervisors (Johnson et al. 2006). In the abusive treatment situation, such supervisory behaviors confirm the gender-dissimilar subordinates’ expectations, resulting in resource losses.

However, compared with gender-similar subordinates, the resource losses to dissimilar subordinates tend to be less severe because they expect mistreatment from their supervisors, and abusive supervision only validates their anticipation. This is in line with the notion of black sheep effects (Marques et al. 1988) that individuals tend to evaluate negative behavior of similar others more extremely than that of dissimilar others. For example, Luksyte et al. (2015) provided evidence that the detrimental effects (i.e., fear, negative affect, deviance) of coworker presenteeism were stronger for racially similar employees than for racially dissimilar employees. Drawing on such a theoretical premise, we suggest that subordinates with gender-dissimilar supervisors experience less psychological distress, and the effect on their silence tends to be weaker compared with that of their counterparts. We posit:

Hypothesis 3

Supervisor–subordinate gender dissimilarity will moderate the indirect relationship between abusive supervision and silence (via psychological distress) such that the relationships are weaker for subordinates with gender-dissimilar supervisors than for those with gender-similar supervisors.

Methods

Study 1

Procedures and Participants

To examine the relationships among our focal variables, we conducted a scenario experiment with a 2 (abusive supervision: high vs. low) by 2 (gender similarity: different vs. same) between-subject design. Data were collected via an online survey with employees working in various companies and industries in China as respondents. A snowballing sampling technique was utilized to recruit participants (Weathington et al. 2010).

The online survey started with an information sheet and a consent form; then, each participant was asked to enter his or her demographic information including gender. Based on participants’ gender information, the survey was programmed to randomly assign participants to one of the four scenarios. For example, if a participant entered his gender information as male in a gender similarity condition, then the name of the supervisor in the scenario (either high or low abusive supervision) would apparently be a male’s name (i.e., Jun Li), and the words “he” and “him” would appear in the scenario referring to the supervisor, representing the same gender. Similarly, for a gender dissimilarity situation, when a participant chose his gender as female, then the name of supervisor in the scenario (either high or low abusive supervision) would typically be a female’s name (i.e., Meimei Han), and the words “she” and “her” would appear in the scenario referring to the supervisor. Participants read one of the four scenarios, each of which instructed the participants to imagine that they are the subordinates of the supervisors in the scenarios (see Appendix. Each scenario included two events an employee faced, one in conversation with his/her supervisor and another in an office meeting, and the supervisor’s reaction is different between high- and low-abusive supervision scenarios.). Following the scenarios, participants completed the measures of abusive supervision, psychological distress, and silence.

In total, 222 participants voluntarily completed the survey. We received 62 responses for the scenario of high abusive supervision and gender similarity, and 52 for the scenario of high abusive supervision and gender dissimilarity. In the low-abusive supervision situation, the numbers of samples for gender similarity and dissimilarity were 52 and 56, respectively. Approximately 63% of the respondents were female. The average age was 27.76, and the average years of total work experience were 4.21. Approximately 60.8% of participants had earned a university degree. They were employed in various industries, such as banking (49.1%), engineering (6.8%), education (4.5%), and manufacturing (3.6%), among others.

Measures

Responses were indicated on a seven-point scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree), unless otherwise noted. We back-translated the questionnaire from English to Chinese as suggested by Brislin (1980).

Abusive Supervision

We measured abusive supervision using Tepper’s (2000) abusive supervision scale. Based on the descriptions of supervisory abusive behaviors in our scenarios, we chose seven items to measure participants’ perceived abusive supervision (i.e., “Ridiculed me,” “Told me my thoughts or feelings were stupid,” “Put me down in front of others,” “Reminded me of my past mistakes and failures,” “Expressed anger at me when he/she was mad at another,” “Was rude to me,” and “Told me I’m incompetent”) (α = 0.96).

Psychological Distress

We measured psychological distress using the scale developed by Derogatis (1993). The scale items measure the extent to which respondents have felt fearful, restless, worthless, and in panic. Each respondent used a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 7 (Extremely) to indicate how he or she felt after being treated by the supervisor in the scenario (α = 0.93).

Gender Dissimilarity

Gender was coded 0 for male and 1 for female. As in prior research (e.g., Avery et al. 2013; Carter et al. 2014), dichotomous dissimilarity scores were coded with 0 to indicate that the subordinate and supervisor were in the same gender category, and 1 to indicate that they were different in gender.

Silence

Researchers have suggested that voice and silence can be conceptualized as opposite ends of a continuum since silence is the failure to voice (Milliken et al. 2003; Morrison 2011). As such, we measured silence by reverse-scoring a six-item voice scale developed by Van Dyne and LePine (1998). We slightly modified the items to capture participants’ behavioral intention to express their ideas and suggestions. Sample items include “I will be willing to speak up in this group with ideas for new projects or changes in procedures” and “I will be willing to speak up and encourage others in this group to get involved in issues that affect the group.” By reverse-scoring the voice data, we created silence scores with a higher value indicating greater intention to remain silent (α = 0.94).

Manipulation Checks

To assess the effectiveness of the abusive supervision manipulation, we conducted analysis of variance tests. With the abusive supervision manipulation check as the outcome, our test results indicated a main effect for the abusive supervision condition (mean high abusive supervision = 3.76, mean low abusive supervision = 2.60, F (1, 220) = 25.21, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.32). We concluded that the abusive supervision manipulation was successful.

Analyses and Results

Study 1 mainly investigated the causal link between abusive supervision and psychological distress, as well as the mediating effect of psychological distress and the moderating effect of gender dissimilarity. Table 1 illustrates the means, standard deviations, coefficient alphas, and intercorrelations among the study variables.Footnote 1

Before testing our hypotheses, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses to test the distinctiveness of the three focal variables (i.e., abusive supervision, psychological distress, and silence) using the M-plus 6.11 program (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2010). The three-factor baseline model fit the data well (χ 2 = 374.82, df = 116, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.10, TLI = 0.92), and all of the standardized factor loadings of all items on their respective constructs were significant (p < 0.01). This baseline model fit the data best compared with the three alternative models in which (a) the correlation between abusive supervision and psychological distress was fixed to one (Δχ 2 = 256.49, Δdf = 2, p < 0.01), (b) the correlation between abusive supervision and silence was fixed to one (Δχ 2 = 1123.26, Δdf = 2, p < 0.01), and (c) the correlations among abusive supervision, psychological distress, and silence were fixed to one (Δχ 2 = 1369.84, Δdf = 3, p < 0.01). Overall, these results indicated the discriminant validity of the three focal variables.

We tested our hypotheses using both manipulated and perceived abusive supervision data (e.g., Farh and Chen 2014). Hypothesis 1 proposed that abusive supervision is positively related to psychological distress. The results of Model 1 (Table 2) show that both manipulated (b = 0.82, p < 0.001) and perceived (b = 0.71, p < 0.001) abusive supervision predicted psychological distress. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that psychological distress mediates the relationship between abusive supervision and silence. To test this mediation hypothesis, we used the product-of-coefficients approach (i.e., testing the statistical significance of the product of a and b—path a is obtained by regressing a mediator on a predictor and path b is obtained by regressing a dependent variable on the mediator and predictor) (MacKinnon et al. 2007). We constructed confidence intervals (CIs) in 20,000 samples for the indirect effects using the bias-corrected bootstrap procedure (Preacher and Hayes 2004). As indicated in Table 2, the results of Model 1 yield significant path a coefficients (abuse manipulations: path a = 0.82, p < 0.001; abuse perceptions: path a = 0.71, p < 0.001), and the results of Model 3 show significant path b (i.e., the relationship between psychological distress and silence) coefficients when abuse manipulations (path b = 0.15, p < 0.01) or abuse perceptions (path b = 0.19, p < 0.01) were the predictor in the respective mediation model. Bias-corrected confidence intervals of the indirect effect excluded zero when abuse manipulations (ab = 0.12, 99% CI [0.02, 0.28]) or abuse perceptions (ab = 0.13, 95% CI [0.00, 0.27]) were the predictor in the respective mediation model. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Hypothesis 3 proposed that supervisor–subordinate gender dissimilarity moderates the indirect effect of abusive supervision on silence (via psychological distress) such that the relationship is weaker for subordinates with gender-dissimilar supervisors than for those with gender-similar supervisors. To test H3, we followed the first-stage moderation model approach of Edwards and Lambert (2007), which allows simultaneous examination of the moderating effects on a mediation model. Following their procedure, we first tested two models (i.e., Models 2 and 3 in Table 2). We then used the path estimates produced from Models 2 and 3 to compute the indirect effect of abusive supervision on silence (via psychological distress) for subordinates with gender-dissimilar supervisors and that for subordinates with gender-similar supervisors. Lastly, the differences in the strength of these two indirect effects were computed. We used 1000 bootstrap samples to construct bias-corrected confidence intervals for the two indirect effects (IEs) and the difference. A first-stage moderation model is supported if the difference in the strength of the two indirect effects is significant. Table 2 shows that with abuse manipulations as the predictor in the mediation model, the indirect effect of abusive supervision on silence (via psychological distress) was not different (d = −0.07, ns) between subordinates with gender-dissimilar supervisors (IE = 0.09, p < 0.05) and subordinates with gender-similar supervisors (IE = 0.16, p < 0.01). Similarly, with abuse perceptions as the predictor in the mediation model, the indirect effect of abusive supervision on silence (via psychological distress) was not different (d = −0.00, ns) between subordinates with gender-dissimilar supervisors (IE = 0.13, p < 0.01) and subordinates with gender-similar supervisors (IE = 0.13, p < 0.01). Therefore, we did not find support for H3.

Discussion

Overall, our results supported Hypotheses 1 and 2, but not Hypothesis 3. Using the experimental study design, we demonstrated the causal link between abusive supervision and psychological distress, as well as the mediating effect of psychological distress on the relationship between abusive supervision and silence. We, however, did not determine the moderating effects of gender dissimilarity on the mediation model. One potential limitation in Study 1 is that participants read scenarios rather than actually experiencing high or low abuses from their supervisors. Second, we could not perform a gender dissimilarity manipulation check because we did not include a survey question that would ask the participants to select the gender information of the supervisor in the scenarios they read. Although the supervisors’ names were gender specific in the scenarios (e.g., in the United States, John is a typical male name and Mary is a typical female name), we did not have evidence that the gender dissimilarity manipulation was successful. Third, participants could not visually observe supervisors’ gender, but simply read scenarios that indicated the gender information of the supervisors. The scenario method, presented in written form, may be a type of low-fidelity simulation (Chan and Schmitt 1997), as opposed to visual and interactive methods. As such, we suspected that the female or male supervisor’s name appearing in the scenario may not have been a strong enough manipulation. For example, Wayne et al. (2001) used a strong manipulation (photographs), rather than subtle manipulations such as the terminology signaling gender information used in our study. Gonzales et al. (1994) directly asked participants to imagine the perpetrators to be the same gender as themselves. We speculated that when individuals interact with their supervisors in general and experience abusive supervision in particular in the workplace, gender dissimilarity would be more salient than in a scenario setting. Thus, in Study 2, we collected field study data to help us further examine our proposed hypotheses.

Study 2

Procedure and Participants

Data for Study 2 were collected from full-time employees of various organizations in South Korea as part of a larger data collection effort. We employed two different methods to recruit participants. First, we invited MBA alumni of a large Korean university to participate in the study and the MBA alumni contacted provided access to their colleagues at their organizations. The alumni filled out an employee survey and asked colleagues in their organizations to fill out the surveys. One of the authors delivered survey packets to the alumni who volunteered to participate, and directly collected the completed surveys from the participants. To create a temporal separation (Podsakoff et al. 2003), we included two separate survey packages (labeled Survey 1 and Survey 2) in each packet and instructed the participants to complete Survey 2 one or two days after the completion of Survey 1. Survey 1 asked the participants to rate items of abusive supervision and the years of working with their supervisors. Survey 2 included items that measured psychological distress and silence along with demographic information. Some participants preferred an online version of the survey. Thus, we sent emails containing a link to an online survey to focal employees. For the online survey, there was no time interval between Survey 1 and Survey 2, but we inserted a different cover webpage for each of the survey. Fifty employees used the online survey, and no significant differences existed in the mean scores for our focal variables between the paper survey and online survey. Out of 350 distributed questionnaires, we received usable data from 251 employees (a 71.7% response rate).

Second, we invited another set of participants who were professional MBA students at another university in South Korea and who worked full-time in their organizations. These MBA students also asked their colleagues in the same organizations to participate in the survey. The MBA students were rewarded with extra credit points for their participation in the survey via their accounting or management classes. We provided survey packets to participants, each of which included two separate survey packages (i.e., Survey 1 and Survey 2) and instructed them to complete each survey on two different days. Completed surveys were returned to the research team in postage-paid envelopes. Out of 250 distributed questionnaires, we received usable data from 151 employees (a 60.4% response rate).

All participants were informed that their participation was voluntary in this study and were assured response confidentiality. Among the respondents, 68% were male, 58% were married, and the mean age was 34.35. The average length of the supervisor–subordinate relationship was 2.3 years. They were employed in various functional areas, including research and design (R&D, 22%), human resources (HR, 21%), finance (11%), sales (11%), business support (9%), and so on.

Because we collected data from two sets of participants (i.e., Group 1 - MBA alumni of one large Korean university and their colleagues, Group 2 - professional MBA students of another Korean university and their colleagues), we performed T-tests to compare their responses to our focal variables. T test results showed that there were no significant differences in abusive supervision (p = 0.22) between Group 1 (M = 1.86, SD = 0.70) and Group 2 (M = 1.94, SD = 0.74). The differences in psychological distress and silence between Group 1 (psychological distress, M = 2.05, SD = 0.87; silence, M = 3.14, SD = 0.91) and Group 2 (psychological distress, M = 2.04, SD = 0.94; silence, M = 3.19, SD = 0.99) were not statistically significant (psychological distress: p = 0.15; silence: p = 0.21).

Measures

We followed the back-translation procedure to translate survey instruments from English to Korean (Brislin 1980).

Abusive Supervision

We assessed abusive supervision with a shortened five-item version of Tepper’s (2000) abusive supervision scale (Mitchell and Ambrose 2007). A sample item reads, “Told me my thoughts or feelings were stupid.” Responses were indicated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (I cannot remember him/her ever using this behavior with me) to 5 (He/She has used this behavior very often with me) (α = 0.89).

Psychological Distress

We used the same measure as that in Study 1 (Derogatis 1993). Respondents used a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely) to indicate how frequently they have been feeling fearful, restless, worthless, and in panic in the past month (α = 0.91).

Gender Dissimilarity

Similar to Study 1, the dichotomous dissimilarity scores on gender were coded with 0 to indicate gender similarity and 1 to indicate gender dissimilarity. In our data, 71% subordinates had same-sex supervisors and 29% had different-sex supervisors.

Silence

Silence was measured using the same scale in Study 1 (Van Dyne and LePine 1998) (α = 0.92). Respondents used a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree) to indicate the extent to which they have engaged in voice behaviors. Similar to Study 1, we reverse-scored voice data to create silence scores.

Marker Variable

Given that we collected data from the same source (i.e., employees), we performed a marker variable analysis (Williams et al. 2010) to examine potential common method variance. To facilitate the study of variables, a marker variable is ideally expected to have a correlation of 0 and it should not be theoretically related to the variables (Williams et al. 2010). We used three items from implicit person theory (IPT) developed by Levy and Dweck (1997) to measure our marker variable. IPT refers to a person’s implicit beliefs regarding the malleability of personal attributes. Responses were indicated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). The three items are “The kind of person someone is, is something very basic about them and it can’t be changed very much,” “People can do things differently, but the important parts of who they are can’t really be changed,” and “As much as I hate to admit it, you can’t teach an old dog new tricks. People can’t really change their deepest attributes” (α = 0.80). The correlations between the marker variables and our focal variables (i.e., abusive supervision, psychological distress, and silence) were statistically insignificant.

Analyses and Results

Table 3 shows the means, intercorrelations, and standard deviations among the variables.Footnote 2

Similar to Study 1, we conducted a series of CFAs to evaluate the distinctiveness of the study variables using the M-plus 6.11 program (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2010). The three-factor baseline model fit the data well (χ 2 = 250.32, df = 87, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.07, TLI = 0.95), and all the standardized factor loadings of all the items on their respective constructs were significant (p < 0.01). This baseline model fit the data best compared with the three alternative models in which a) the correlation between abusive supervision and psychological distress was fixed to one (Δχ 2 = 1064.50, Δdf = 2, p < 0.01), b) the correlation between abusive supervision and silence was fixed to one (Δχ 2 = 1524.11, Δdf = 2, p < 0.01), and c) the correlations among abusive supervision, psychological distress, and silence were fixed to one (Δχ 2 = 2048.83, Δdf = 3, p < 0.01). These results indicated the discriminant validity of our three focal variables.

Before testing the hypotheses, we conducted a common method variance (CMV) analysis by following the procedures suggested by Williams et al. (2010). Phase I involves model comparisons that test for the presence of method effects associated with the marker variable (Williams et al. 2010). As shown in Table 4, the Chi square difference tests yielded non-significant results among model comparisons, namely a) between the indicated Baseline Model and Method-C Model (∆χ2 = 0.37, ∆df = 1, ns), b) between the Method-U and Method-C Models (∆χ2 = 7.44, ∆df = 14, ns), and c) between the Method-C and Method-R Models (∆χ2 = 7.44, ∆df = 11, ns). These results indicated no significant presence of method variance associated with IPT, suggesting that CMV would not to be a concern in Study 2. As such, we did not perform either Phase II to quantify the amount of method variance associated with the measurement of the study variables or Phase III to examine the effect of marker-based method variance on factor correlations among the study variables.

Hypothesis 1 predicted that abusive supervision is positively related to psychological distress. Model 1 in Table 5 shows that the effect of abusive supervision on psychological distress was significant (b = 0.32, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Hypothesis 2 proposed that psychological distress mediates the relationship between abusive supervision and silence. Similar to Study 1, we used the product-of-coefficients approach to construct confidence intervals (CIs) in 20,000 bootstrap samples for the indirect effects (MacKinnon et al., 2007; Preacher and Hayes 2004). As indicated in Table 5, the results of Model 1 show a significant path a coefficient (i.e., the relationship between abusive supervision and psychological distress) (path a = 0.32, p < 0.001), and the results of Model 3 show a significant path b coefficient (i.e., the relationship between psychological distress and silence) (path b = 0.31, p < 0.001). In further support of H2, bias-corrected confidence intervals of the indirect effect exclude zero (ab = 0.10, 99% CI [0.04, 0.17]).

Hypothesis 3 proposed that supervisor–subordinate gender dissimilarity moderates the indirect effect of abusive supervision on silence (via psychological distress) such that the relationship is weaker for subordinates with gender-dissimilar supervisors than for those with gender-similar supervisors. Similar to Study 1, we followed the first-stage moderation model approach of Edwards and Lambert (2007) to test H3. Table 5 shows that the indirect effect of abusive supervision on silence (via psychological distress) was weaker (d = −0.09, p < 0.05) for subordinates with gender-dissimilar supervisors (IE = 0.04, ns) than for subordinates with gender-similar supervisors (IE = 0.13, p < 0.01). We created a plot using points that were one standard deviation above and below the mean of abusive supervision across two levels of the moderator. Figure 2 depicts the moderating effect that the indirect effect of abusive supervision on silence (transmitted via psychological distress) was weaker for subordinates with gender-dissimilar supervisors than for those with gender-similar supervisors. Thus, H3 was supported.

Discussion

The results from Study 2 provided support for the predicted relationships. Using a field study setting, we were able to corroborate the findings in Study 1 such that abusive supervision affected employee’s psychological wellbeing, and that psychological distress mediated the relationship between abusive supervision and silence. More importantly, we were able to demonstrate that the relational context comprising supervisor and subordinate (i.e., gender dissimilarity) moderated the mediating effect of abusive supervision on employee silence via psychological distress.

General Discussion

Although sparse, research that examines potential mediating and moderating effects on the relationship between abusive supervision and outcome variables has recently begun (e.g., Restubog et al. 2011; Tepper et al. 2008). Drawing upon COR theory, we contributed to this line of inquiry by simultaneously examining why abused employees were silent and how their relational social context (i.e., supervisor–subordinate gender dissimilarity) influenced their silence behaviors. We found the causal path linking abusive supervision and psychological distress in our experimental study. In both experimental and field studies, we further provided evidence that psychological distress mediated the relationship between abusive supervision and silence. Lastly, our field study demonstrated that this mediation effect was contingent upon the relational context comprising supervisor and subordinate.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

Although abusive supervision research has suggested that abused employees experience detrimental psychological consequences (e.g., psychological distress, emotional exhaustion), such a causal inference has not been established (Martinko et al. 2013; Mackey et al. 2015). Accordingly, we conducted Study 1 to examine such a link using an experimental design and found that abused employees were distressed psychologically. Using the perceived abusive supervision data in Study 1 and Study 2, we provided corroborating evidence for such a link; thus, our study presents initial evidence as to the causal inferences of such a supervisory behavior on employees’ psychological wellbeing.

Second, our study contributes to the silence literature by examining the antecedent and underlying mechanism of silence (cf. Xu et al. 2015). Researchers suggest that employees’ decisions to remain silent can significantly affect organizations and the people within them (Morrison 2014). For example, performance may suffer when employees withhold their suggestions and information regarding work-related problems or new ideas to improve the functionality of their work processes (e.g., Milliken et al. 2003). Drawing on COR theory, we reasoned that supervisor abusiveness depletes subordinates’ resources by stimulating a high level of cognitive arousal (Ursin and Eriksen 2004) resulting in high levels of psychological distress. To conserve their remaining resources and prevent further resource losses, distressed employees tend to remain silent (cf. Xu et al. 2015). In both the experimental and field studies, we demonstrated that abusive supervision is the inhibitor that pushed distressed employees toward silence.

Third, we contribute to the abusive supervision and silence literature by exploring the effect of the relational context of supervisors and subordinates. Researchers have begun to understand why abusive supervision affects employees differently (e.g., Restubog et al. 2011). Most recently, Xu et al. (2015) presented evidence that leader–member exchange (LMX) moderated the relationship between abusive supervision and emotional exhaustion such that abused employees are more exhausted emotionally when LMX is high. Instead of the supervisor–subordinate relationship quality (i.e., LMX), our study examined the moderating role of the relationship context comprising supervisor and subordinate in the form of gender dissimilarity. Varma and Stroh (2001) suggested that supervisor–subordinate gender composition has a stronger effect than LMX on subordinate performance ratings. Nevertheless, similar to the findings of Xu et al. (2015), the results from Study 2 suggest that employees with gender-similar supervisors, as opposed to those with gender-dissimilar supervisors, are affected more strongly on their psychological state and the subsequent silence behavior. These findings are in line with social identity theory (Ashforth et al. 2008; Tajfel and Turner 1986), which states that gender similarity signals in-group membership status and subordinates tend to receive higher levels of support from their gender-similar supervisors. When this expectation has been violated, employees with gender-similar supervisors may suffer more and experience a higher level of psychological distress than those with gender-dissimilar supervisors (cf. Luksyte et al. 2015). Thus, future research should investigate how unmet or under-met expectations (cf. Schaubroeck et al. 2008) evolve over time and affect the level of psychological distress.

However, the interpretation of our results for moderated mediation effects (Hypothesis 3) may require some caution because we only found support for this hypothesis in Study 2, but not in Study 1. Participants read scenarios without visually observing supervisors’ gender or actually experiencing supervisory abuses in Study 1. As previously discussed, we speculated that the female or male supervisor’s name appearing in the scenario may not be a strong enough manipulation. Nevertheless, future research might consider conducting experimental studies using more visual and interactive methods (e.g., Klapper et al. 2016; Wayne et al. 2001) to manipulate gender dissimilarity and abusive supervision.

Our study provides practical implications for management practices. First, creating a safe work environment is important to prevent the occurrence of abusive supervision. Hostile work environments may become a breeding ground for abusiveness (Mawritz et al. 2014), and this type of atmosphere may reinforce interpersonal deviant behaviors among group members (Mawritz et al. 2012). Organizations should exert significant efforts to create a positive, supportive climate. Furthermore, organizations should review their policies and practices that may unintentionally motivate or incentivize negative behaviors and create a hostile environment.

Second, organization leaders should heighten their awareness with regard to the effect of their supervisory behaviors (e.g., abusive supervision) on their employees’ psychological wellbeing. Supervisors who have experienced abusive supervision from their bosses may treat their subordinates with similar negative behaviors (Mawritz et al. 2012). Leaders’ abusive behaviors prohibit the creation of a climate where employees can express new ideas and different perspectives without fear (Edmondson 1999), thus pushing them toward silence. By contrast, positive supervisory behaviors (e.g., LMX) can be a motivator that increases employee engagement in voice (e.g., Liu et al. 2013). To this end, organizations should establish norms of appropriate supervisory behaviors and educate managers on the norms as well as the consequences of inappropriate behaviors.

Third, given the negative psychological effects of abusive supervision, organizations may consider providing their members with employee assistance programs to help them manage work- (and family-) related problems and stress. Furthermore, given that abusive supervision denotes a costly and frequently harmful problem for organizations and their members (Tepper 2007), organizations may consider providing opportunities for employees to anonymously report occurrences of supervisor abuse.

Limitations and Future Research

Despite the importance of our findings, this study is not without limitations. One of them is the cross-sectional design of Study 2. In Study 1, we conducted scenario experiments, but the mediator and outcome variables were collected at the same point in time. The cross-sectional nature of this research prevents the confirmation of the causal inferences implied by our mediation model. Future study may consider utilizing a longitudinal design to test the mediation model.

A second limitation of this study is that responses came from the same source. Despite our attempt to create a temporal separation (Podsakoff et al. 2003) in Study 2 (i.e., two surveys separating the measurement of the predictor and criterion variables for each participant), the time delay of one or two days might be too short. Thus, we conducted a CMV analysis using the procedure suggested by Williams et al. (2010) and found that CMV was not a major concern. Nevertheless, future research may benefit from collecting data from multiple sources (e.g., subordinate, supervisor, skip-level leader; Liu et al. 2013). Third, we did not perform a gender dissimilarity manipulation check. Future research may use high-fidelity methods (Chan and Schmitt 1997) to manipulate abusive supervision and gender dissimilarity. For example, video recording technology may provide indispensable information that cannot easily be captured by written scenarios (Congdon et al. 2016).

Fourth, as our data were collected in China (Study 1) and South Korea (Study 2), which are countries that value power and authority (Ashkanasy 2002), questions could be raised regarding the findings’ generalizability. Both Chinese and Korean societies are high in power distance compared with Western societies, such as the United States and Britain (Hofstede 2001), and employees in the former societies may be more tolerant of supervisory abuses (cf., Lian et al. 2012). In fact, Vogel et al. (2015) found that culture moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and interpersonal justice such that the negative relationship is stronger for subordinates in the Anglo culture (i.e., the U.S. and Australia) than for those in the Confucian Asian culture (i.e., Taiwan and Singapore). Extrapolating from Vogel et al.’s study, we expect that our proposed model would be supported in the Western context, but the strength of the relationships could differ. For instance, the reaction from abusive supervision (i.e., psychological distress) may be more negative for subordinates in the Western culture than for their counterparts in China or Korea. Future research should examine our study model in a Western setting and explore the existence of cross-cultural effects. Furthermore, given that both China and Korea are ethnically homogeneous societies (Afridi et al. 2015; Kim 2009), we did not include the race composition of the supervisor and subordinate dyads (another easily observable demographic attribute) (e.g., Carter et al. 2014; Luksyte et al. 2015). Future research may benefit from investigating the effects of other salient relational demographic variables, such as race dissimilarity and personality dissimilarity.

Fifth, we did not measure actual abusive supervision behaviors, given that differences may exist between subordinates’ perceptions of abusive supervision and actual supervisor behaviors (Martinko et al. 2013; Mackey et al. 2015). Instead, following a similar procedure (Farh and Chen 2014), we designed scenario experiments (Study 1) where abusive supervision was the proxy for abusive behaviors. Future research should devote extra attention to creating methods by using technology to capture objectively abusive supervision behaviors and the occurrences of abusive events, as well as their immediate effect on subjects, such as cardiovascular, biochemical, or gastrointestinal symptoms (Fried et al. 1984).

Additionally, given that some scholars have advocated that voice and silence can be viewed as opposite ends of a single continuum (Ashford et al. 2009; Morrison 2011), we operationalized silence by reverse-scoring voice data measured with the voice scale (Van Dyne and LePine 1998). Other scholars have suggested that voice and silence should be treated as separate constructs and that existing measures of voice could not necessarily be used to infer silence (Morrison 2014; Morrison et al. 2015). Future research may benefit from measuring silence using existing silence scales (e.g., Morrison et al. 2015) and more importantly from providing careful empirical evidence distinguishing voice and silence (Ashford et al. 2009).

Finally, the current study focused on the detrimental effects of abusive supervision on subordinate silence (via psychological distress) and on the moderating role of supervisor–subordinate gender dissimilarity. However, few recent studies have examined the roles of third party observers or bystanders who witness mistreatment at work. Reich and Hershcovis (2015) emphasized the importance of investigating the responses of bystanders who are other employees in a group not directly involved in workplace mistreatment but have observed it. For example, the bystanders would feel angry, which might motivate them to engage in supervisor-directed deviance (Mitchell et al. 2015). Future research may investigate how third party observers and bystanders play a role in creating a positive climate and how they affect the victims and other group members’ silence when they witness supervisory abuse.

Conclusion

Despite its low base rate, abusive supervision has been suggested to be detrimental to individual wellbeing and to affect subordinates’ behaviors (Tepper 2007; Mackey et al. 2015). The present study substantiates the causal relationship between abusive supervision and psychological distress. Our findings indicate that psychological distress plays a mediating role in the relationship between abusive supervision and silent behavior. More importantly, the results from Study 2 suggest that supervisor–subordinate gender dissimilarity moderates the mediation model such that the mediating effect of abusive supervision on silence is stronger for subordinates with a gender-similar supervisor. Using both a scenario-based experiment and a field study, our research contributes to the abusive supervision and silence literature.

Notes

We also tested our hypotheses controlling for supervisor gender, subordinate gender, age, and job tenure. The results are comparable with those reported in our paper without any control variables.

We also tested our hypotheses controlling for supervisor gender, subordinate gender, age, marital status, and dyadic tenure. The results are comparable with those reported in our paper without any control variables.

References

Afridi, F., Li, S. X., & Ren, Y. (2015). Social identity and inequality: The impact of China’s hukou system. Journal of Public Economics, 123, 17–29.

Aryee, S., Chen, Z. X., Sun, L. Y., & Debrah, Y. A. (2007). Antecedents and outcomes of abusive supervision: Test of a trickle-down model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 191–201.

Ashford, S. J., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Christianson, M. K. (2009). Speaking up and speaking out: The leadership dynamics of voice in organizations. In J. Greenberg & M. Edwards (Eds.), Voice and silence in organizations (pp. 175–202). Bingley, England: Emerald.

Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34(3), 325–374.

Ashkanasy, N. M. (2002). Leadership in the Asian century: Lessons from GLOBE. International Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 5(3), 150–163.

Avery, D. R., Wang, M., Volpone, S. D., & Zhou, L. (2013). Different strokes for different folks: The impact of sex dissimilarity in the empowerment–performance relationship. Personnel Psychology, 66(3), 757–784.

Avey, J. B., Wu, K., & Holley, E. (2014). The influence of abusive supervision and job embeddedness on citizenship and deviance. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(3), 721–731.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 389–444). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Carter, M. Z., Mossholder, K. W., Feild, H. S., & Armenakis, A. A. (2014). Transformational leadership, interactional justice, and organizational citizenship behavior: The effects of supervisor–subordinate racial and gender dissimilarity. Group and Organization Management, 39(6), 691–719.

Chan, D., & Schmitt, N. (1997). Video-based versus paper-and-pencil method of assessment in situational judgment tests: Subgroup differences in test performance and face validity perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(1), 143–159.

Chan, M. L. E., & McAllister, D. J. (2014). Abusive supervision through the lens of employee state paranoia. Academy of Management Review, 39(1), 44–66.

Congdon, E. L., Novack, M. A., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2016). Gesture in experimental studies: How videotape technology can advance psychological theory. Organizational Research Methods. doi:10.1177/1094428116654548.

Derogatis, L. R. (1993). BSI brief symptom inventory. Administration, scoring, and procedures manual (4th ed.). Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22.

Farh, C. I. C., & Chen, Z. (2014). Beyond the individual victim: Multilevel consequences of abusive supervision in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(6), 1074–1095.

Ferris, D. L., Yan, M., Lim, V., Chen, Y., & Fatimah, S. (2016). An approach/avoidance framework of workplace aggression. Academy of Management Journal, 59, 1777–1800.

Foley, S., Linnehan, F., Greenhaus, J. H., & Weer, C. H. (2006). The impact of gender similarity, racial similarity, and work culture on family-supportive supervision. Group and Organization Management, 31(4), 420–441.

Fried, Y., Rowland, K. M., & Ferris, G. R. (1984). The physiological measurement of work stress: A critique. Personnel Psychology, 37(4), 583–615.

Gonzales, M. H., Haugen, J. A., & Manning, D. J. (1994). Victims as “narrative critics”: Factors influencing rejoinders and evaluative responses to offenders’ accounts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(6), 691–704.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in Conservation of Resources Theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364.

Harris, K. J., Kacmar, K. M., & Zivnuska, S. (2007). An investigation of abusive supervision as a predictor of performance and the meaning of work as a moderator of the relationship. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 252–263.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524.

Hobfoll, S. E., & Shirom, A. (2001). Conservation of resource theory: Applications to stress and management in the workplace. In R. T. Golembiewski (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior (2nd ed., pp. 57–80). New York: Marcel Dekker.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Johnson, R. E., Selenta, C., & Lord, R. G. (2006). When organizational justice and the self-concept meet: Consequences for the organization and its members. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 99(2), 175–201.

Kim, A. E. (2009). Global migration and South Korea: Foreign workers, foreign brides and the making of a multicultural society. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32(1), 70–92.

Kim, S. L., Kim, M., & Yun, S. (2015). Knowledge sharing, abusive supervision, and support: A social exchange perspective. Group and Organization Management, 40(5), 599–624.

Kim, S. L., & Yun, S. (2015). The effect of coworker knowledge sharing on performance and its boundary conditions: An interactional Perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 575–582.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., & Edmondson, A. C. (2009). Silenced by fear: The nature, sources, and consequences of fear at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 29, 163–193.

Klapper, A., Dotsch, R., van Rooij, I., & Wigboldus, D. H. J. (2016). Do we spontaneously form stable trustworthiness impressions from facial appearance? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111, 655–664.

Lee, S., Yun, S., & Srivastava, A. (2013). Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between abusive supervision and creativity in South Korea. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(5), 724–731.

Levy, S. R., & Dweck, C. S. (1997). Implicit theory measures: Reliability and validity data for adults and children. Columbia University.

Lian, H., Ferris, D. L., & Brown, D. J. (2012). Does power distance exacerbate or mitigate the effects of abusive supervision? It depends on the outcome. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 107–123.

Lin, W., Wang, L., & Chen, S. (2013). Abusive supervision and employee well-being: The moderating effect of power distance orientation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 62(2), 308–329.

Liu, W., Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2013). The relational antecedents of voice targeted at different leaders. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(5), 841–851.

Luksyte, A., Avery, D. R., & Yeo, G. (2015). It is worse when you do it: Examining the interactive effects of coworker presenteeism and demographic similarity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1107–1123.

Mackey, J. D., Frieder, R. E., Brees, J. R., & Martinko, M. J. (2015). Abusive supervision: A meta-analysis and empirical review. Journal of Management. doi:10.1177/0149206315573997.

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 593–614.

Marques, J. M., Yzerbyt, V. Y., & Leyens, J. P. (1988). The “black sheep effect”: Extremity of judgments towards ingroup members as a function of group identification. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18, 1–16.

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., Brees, J. R., & Mackey, J. (2013). A review of abusive supervision research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(1), 120–137.

Mawritz, M. B., Dust, S. B., & Resick, C. J. (2014). Hostile climate, abusive supervision, and employee coping: Does conscientiousness matter? Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(4), 737–747.

Mawritz, M. B., Mayer, D. M., Hoobler, J. M., Wayne, S. J., & Marinova, S. V. (2012). A trickle-down model of abusive supervision. Personnel Psychology, 65(2), 325–357.

McCann, C. D., Ostrom, T. M., Tyner, L. K., & Mitchell, M. L. (1985). Person perception in heterogeneous groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(6), 1449–1459.

Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., & Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1453–1476.

Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2007). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1159–1168.

Mitchell, M. S., Vogel, R. M., & Folger, R. (2015). Third parties’ reactions to the abusive supervision of coworkers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1040–1055.

Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. The Academy of Management Annuals, 5, 373–412.

Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 173–197.

Morrison, E. W., See, K. E., & Pan, C. (2015). An approach-inhibition model of employee silence: The joint effects of personal sense of power and target openness. Personnel Psychology, 68(3), 547–580.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Nandkeolyar, A. K., Shaffer, J. A., Li, A., Ekkirala, S., & Bagger, J. (2014). Surviving an abusive supervisor: The joint roles of conscientiousness and coping strategies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(1), 138–150.

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2012). Employee voice behavior: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 216–234.

Nielsen, M. B., & Einarsen, S. (2012). Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work & Stress, 26(4), 309–332.

Palanski, M., Avey, J. B., & Jiraporn, N. (2014). The effects of ethical leadership and abusive supervision on job search behaviors in the turnover process. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(1), 135–146.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Preacher, K., & Hayes, A. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, 36(4), 717–731.

Reich, T. C., & Hershcovis, M. S. (2015). Observing workplace incivility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 203–215.

Restubog, S. L. D., Scott, K. L., & Zagenczyk, T. J. (2011). When distress hits home: The role of contextual factors and psychological distress in predicting employees’ responses to abusive supervision. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 713–729.

Riordan, C. M., & Shore, L. M. (1997). Demographic diversity and employee attitudes: An empirical examination of relational demography within work units. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(3), 342–358.

Schaubroeck, J., Shaw, J. D., Duffy, M. K., & Mitra, A. (2008). An under-met and over-met expectations model of employee reactions to merit raises. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 424–434.

Schaubroeck, J. M., Peng, A. C., & Hannah, S. T. (2016). The role of peer respect in linking abusive supervision to follower outcomes: Dual moderation of group potency. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(2), 267–278.

Spector, P. E., & Jex, S. M. (1998). Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal conflict at work scale, organizational constraints scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3(4), 356–367.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson Hall.

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. The Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190.

Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33(3), 261–289.

Tepper, B. J., Henle, C. A., Lambert, L. S., Giacalone, R. A., & Duffy, M. K. (2008). Abusive supervision and subordinates’ organization deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4), 721–732.

Tepper, B. J., Moss, S. E., Lockhart, D. E., & Carr, J. C. (2007). Abusive supervision, upward maintenance communication, and subordinates’ psychological distress. Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), 1169–1180.

Thau, S., Bennett, R. J., Mitchell, M. S., & Marrs, M. B. (2009). How management style moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and workplace deviance: An uncertainty management theory perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(1), 79–92.

Thau, S., & Mitchell, M. S. (2010). Self-gain or self-regulation impairment? Tests of competing explanations of the supervisor abuse and employee deviance relationship through perceptions of distributive justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(6), 1009–1031.

Tsui, A. S., & O’Reilly, C. A. (1989). Beyond simple demographic effects: The importance of relational demography in superior–subordinate dyads. Academy of Management Journal, 32(2), 402–423.

Ursin, H., & Eriksen, H. R. (2004). The cognitive activation theory of stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(5), 567–592.

Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 108–119.

van Knippenberg, D., & Hogg, M. A. (2003). A social identity model of leadership effectiveness in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, 243–295.

Varma, A., & Stroh, L. K. (2001). The impact of same-sex LMX dyads on performance evaluations. Human Resource Management, 40(4), 309–320.

Vogel, R. M., Mitchell, M. S., Tepper, B. J., Restubog, S. L. D., Hu, C., Hua, W., et al. (2015). A cross-cultural examination of subordinates’ perceptions of and reactions to abusive supervision. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(5), 720–745.

Wang, G., Harms, P. D., & Mackey, J. D. (2014). Does it take two to tangle? Subordinates’ perceptions of and reactions to abusive supervision. Journal of Business Ethics, 131(2), 487–503.

Wayne, J. H., Riordan, C. M., & Thomas, K. M. (2001). Is all sexual harassment viewed the same? Mock juror decisions in same- and cross-gender cases. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 179–187.

Weathington, B. L., Cunningham, C. J. L., & Pittenger, D. J. (2010). Research methods for the behavioral and social sciences. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Whitman, M. V., Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Holmes, O. (2014). Abusive supervision and feedback avoidance: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(1), 38–53.

Williams, L. J., Hartman, N., & Cavazotte, F. (2010). Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 477–514.

Xu, A. J., Loi, R., & Lam, L. W. (2015). The bad boss takes it all: How abusive supervision and leader–member exchange interact to influence employee silence. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(5), 763–774.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare(s) that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Study 1: The research project has been reviewed according to the ethical review processes in place in the University of Nottingham Ningbo. These processes are governed by the University’s Code of Research Conduct and Research Ethics. Any questions regarding human rights as a research subject may be addressed to UNNC Research Ethics Sub-Committee Coordinator: Joanna.Huang@nottingham.edu.cn. Please refer to http://www.nottingham.edu.cn/en/research/researchethics/unnc-research-code-of-conduct.aspx. An anonymous online-based questionnaire was distributed to the participants and the data was treated anonymously and confidentially. The participant information sheet was shown to them and they were asked to choose “agree” or “disagree” button to participate in the survey. Study 2: The research project has been reviewed according to the ethical review processes in place in the University of Houston. These processes are governed by the University of Houston committee for the protection of human subjects. Any questions regarding human rights as a research subject may be addressed to the University of Houston committee for the protection of human subjects (713-743-9204). Please refer to http://www.uh.edu/research/compliance/irb-cphs/. Informed consent was obtained from individual participants who completed the paper survey. Some participants preferred an online version of the survey. The data was treated anonymously and confidentially. Informed consent was shown to them and they were asked to choose “agree” or “disagree” button to participate in the survey.

Additional information

Joon Hyung Park and Min Z. Carter contributed equally to this work.

Appendix: Scenarios

Appendix: Scenarios

Scenario 1 (Low Abusive Supervision/Gender Similarity)

(1) Participant’s gender = male

(Part 1) A conversation with your supervisor (male)

Jun Li (李军) is your direct supervisor. He has worked in the current organization for 15 years. He asked you to prepare some reports similar to those you have done many times. After completing the reports, you entered his office and presented the reports to be signed. He skimmed through them and spotted a few mistakes. He told you, “There are a few mistakes. Please don’t make the same mistakes in the future. However, you made some interesting and useful points in the report. It seems that you have paid attention to what I advised. I can tell you have made improvement in these two months!”He said encouragingly, “I value your contributions and your competence to deliver high quality work. Please keep up the good work.”

(Part 2) In an office meeting

Jun Li (李军) is usually patient even when he doesn’t get the answers that he wants in an office meeting. He asked you a question in a meeting. You couldn’t answer the question quickly, because it was a bit vague. As you were thinking about how to address his question, he said, “Maybe my question wasn’t clear. Well, let me rephrase it;” and he continued by addressing your colleagues at the meeting, “Also, I appreciate input from all of you. Please feel free to chime in with your perspectives.”

(2) Participant’s gender = female

(Part 1) A conversation with your supervisor (female)

Meimei Han (韩梅梅) is your direct supervisor. She has worked in the current organization for 15 years. She asked you to prepare some reports similar to those you have done many times. After completing the reports, you entered her office and presented the reports to be signed. She skimmed through them and spotted a few mistakes. She told you, “There are a few mistakes. Please don’t make the same mistakes in the future. However, you made some interesting and useful points in the report. It seems that you have paid attention to what I advised. I can tell you have made improvement in these two months!”She said encouragingly, “I value your contributions and your competence to deliver high quality work. Please keep up the good work.”

(Part 2) In an office meeting

Meimei Han (韩梅梅) is usually patient even when she doesn’t get the answers that she wants in an office meeting. She asked you a question in a meeting. You couldn’t answer the question quickly, because it was a bit vague. As you were thinking about how to address her question, she said, “Maybe my question wasn’t clear. Well, let me rephrase it;” and she continued by addressing your colleagues at the meeting, “Also, I appreciate input from all of you. Please feel free to chime in with your perspectives.”

Scenario 2 (High Abusive Supervision/Gender Similarity)

(1) Participant’s gender = male

(Part 1) A conversation with your supervisor (male)