Abstract

This paper examines how employees react to their organizations’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. Drawing upon research in internal marketing and psychological contract theories, we argue that employees have multi-faceted job needs (i.e., economic, developmental, and ideological needs) and that CSR programs comprise an important means to fulfill developmental and ideological job needs. Based on cluster analysis, we identify three heterogeneous employee segments, Idealists, Enthusiasts, and Indifferents, who vary in their multi-faceted job needs and, consequently, their demand for organizational CSR. We further find that an organization’s CSR programs generate favorable employee-related outcomes, such as job satisfaction and reduction in turnover intention, by fulfilling employees’ ideological and developmental job needs. Finally, we find that CSR proximity strengthens the positive impact of CSR on employee-related outcomes. This research reveals significant employee heterogeneity in their demand for organizational CSR and sheds new light on the underlying mechanisms linking CSR to employee-related outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR), broadly defined as discretionary organizational policies and practices that attempt to promote long-term economic, social, and environmental well-being (McWilliams and Siegel 2000; Schwartz and Carroll 2003), has become a strategic imperative today. More and more organizations across the globe are leveraging CSR to gain competitive advantage and achieve long-term success (Du et al. 2011; Surroca et al. 2010; Porter and Kramer 2011). According to a large-scale survey of executives and CSR professionals by McKinsey, one of the key pathways through which CSR can create business value is by enhancing employee morale and reducing employee turnover (Bonini et al. 2009). For any organization, skilled, talented, and motivated employees comprise a critical factor for sustained organizational success (Brammer et al. 2007; Greening and Turban 2000). Thus, advancing our understanding of whether, how, and why employees respond to CSR would help organizations effectively design and implement CSR programs capable of fulfilling employee needs and thus maximizing business returns.

Motivated, at least in part, by the mounting importance of CSR, a growing body of research has investigated employee reactions to CSR and, in general, found that it has a positive impact on various employee-related outcomes, such as organizational attractiveness to prospective employees (Greening and Turban 2000), employee justice perceptions (Rupp et al. 2006), organizational commitment (Brammer et al. 2007), job satisfaction (Herrbach and Mignonac 2004; Valentine and Fleischman 2008), and employee loyalty (Bhattacharya et al. 2008, 2011). Further, a few studies have started to explore the psychological mechanisms underlying the positive effects of CSR on employee-related outcomes. For instance, drawing on social identity theory (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Dutton et al. 1994), Kim et al. (2010) finds that CSR enhances perceived external prestige and employee-organization identification, which then lead to increased employee commitment.

Although this line of research has yielded substantial insights, our understanding of employee reactions to CSR remains limited, propelling scholars to call for more research on this urgent topic (Aguilera et al. 2007; Mueller et al. 2012; Rodrigo and Arenas 2008). In particular, two key issues stand in the way of a deeper understanding of employee reactions to CSR. First, while CSR research focusing on external stakeholders (e.g., customers) has highlighted individual differences as a key factor accounting for the variability in the business returns to CSR (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001; Sen et al. 2009), research focusing on employees has yet to take such a finer-grained approach. Rodrigo and Arenas (2008, p. 266) insightfully commented, “… (even) less attention has been devoted to the differences among employees in relation to CSR, presupposing that this group’s expectations, views, and attitudes were homogeneous.” Second, extant research has paid inadequate attention to the mechanisms underlying employee reactions to CSR. Not only have prior perspectives been limited to theories of social identity and identification (e.g., Brammer et al. 2007; Greening and Turban 2000; Peterson 2004), but also the emergent mechanisms have remained largely untested (see Kim et al. 2010 for a notable exception). In the words of Bhattacharya et al. (2008, p. 38), “companies do not fully understand the psychological mechanisms that link their CSR programs to anticipated positive returns from their employees.”

This research seeks to advance our understanding of employee reactions to CSR by addressing the above mentioned gaps. Drawing upon internal marketing theory (Berry and Parasuraman 1992; Bhattacharya et al. 2008; Vasconcelos 2008) and the literature on psychological contract (Rousseau and McLean Parks 1993; Thompson and Bunderson 2003), we conceptualize employees’ jobs as comprising a multi-faceted bundle of economic, developmental, and ideological attributes. We further theorize that employees are heterogeneous in terms of their multi-faceted job needs and that, when designed properly, CSR programs can differentially fulfill such needs, producing positive employee-related outcomes such as increased job satisfaction and reduced turnover intention. Results from our field survey provide support for our predictions.

In doing so, this research makes two key contributions. First, we document significant employee heterogeneity in their multi-faceted job needs and, relatedly, their demand for organizational CSR programs. Through cluster analysis, we identify three distinct employee segments, Idealists, Enthusiasts, and Indifferents, who vary in their multi-faceted job needs and hence in their demand for CSR. Our findings highlight the importance of exploring employee-specific characteristics in CSR research (Rodrigo and Arenas 2008). Second, this research advances our understanding of the psychological processes linking CSR to employee-related outcomes. We demonstrate the mediating roles of both developmental and ideological job needs fulfillment in the CSR—employee outcome linkages. Specifically, we find that organization’s CSR programs serve to enhance the “job-products”; it offers to its internal customers (i.e., employees), leading to better fulfillment of their multi-faceted job needs and producing, consequently, more satisfied and loyal employees. In this, our research complements the social identity perspective on employee reactions to CSR (Kim et al 2010; Peterson 2004). Our study suggests that, in addition to social identity theory, internal marketing theory and psychological contract theory are relevant conceptual lenses that can enrich and deepen our understanding of employee reactions to CSR.

Finally, our research implicates CSR proximity, i.e., the degree to which employees are aware of and/or involved in their organizations’ CSR activities, as a key lever that can enhance or diminish the relationships between organizational CSR, fulfillment of employees’ ideological and developmental job needs, and employee outcomes (i.e., satisfaction and turnover intention). This points to the need for organizations wishing to reap greater employee-related benefits from CSR to not only effectively communicate such programs to their internal customers but also, ideally, engage them actively in their CSR efforts (Du et al. 2010, 2011; Dawkins 2004).

CSR

The notion of CSR has evolved over the decades. In his classic paper, Carroll (1979, p. 500) defined CSR as “encompassing the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations that society has of organizations at a given point in time.” More recently, Schwartz and Carroll (2003) use a Venn diagram to depict a firm’s economic, legal, and ethical responsibilities, and emphasize that these domains are not mutually exclusive but often overlap substantially with each other. Recent developments in the CSR literature, such as the notions of “strategic CSR” (Kotler and Lee 2005) and “shared (social and business) value creation” (Porter and Kramer 2011), confirm the idea that there exists convergence of interests among a firm’s long-term economic, legal, and ethical responsibilities. An important characteristic of CSR is the discretionary, or voluntary, nature of these activities (Dahlsrud 2008). In other words, CSR consists of discretionary activities that go beyond a firm’s economic interests or legal requirements to promote the broader, long-term social/environmental well-being (McWilliams and Siegel 2000).

A firm’s CSR activities range from philanthropy, cause-related marketing, employee benefits, community outreach, to eco-friendly or, more broadly, sustainable business practices. According to stakeholder theory (Freeman et al. 2007), a firm interacts with primary stakeholders, who are essential to the operation of the business (e.g., consumers, employees, and investors), and secondary stakeholders, who can influence the firm’s business operation only indirectly (i.e., community, government, and the natural environment). Through CSR activities, a firm promotes the well-being of its stakeholders and builds stronger relationships with them.

Through properly designed CSR programs, firms can reap substantial business benefits due to a more positive image as well as enhanced stakeholder relationships, such as greater stakeholder satisfaction and loyalty (Kim et al. 2010; Rodrigo and Arenas 2008). Further, the resource-based view of the firm suggests that CSR can help cultivate fundamental firm-specific intangible resources, such as human resources, favorable corporate culture, and innovation (Branco and Rodrigues 2006; Litz 1996; Surroca et al. 2010). While a comprehensive review of the business returns to CSR is beyond the scope of this paper, it is worth noting that our extant understanding of how employees, a key stakeholder group, react to CSR remains rather limited. In particular, as we pointed out earlier, heterogeneity in employee demand for CSR and the psychological processes underlying employee reactions to CSR comprise two under-investigated yet important topics (Bhattacharya et al. 2008; Rodrigo and Arenas 2008).

Multi-Faceted Job Needs

Internal marketing theory (Berry and Parasuraman 1992; Bhattacharya et al. 2008; Vasconcelos 2008) emphasizes the importance of organizations being centered on fulfilling the job needs of its internal customers, namely, employees. Berry and Parasuraman (1992) define internal marketing as “attracting, developing, motivating, and retaining qualified employees through job-products that satisfy their needs.” Analogous to the way that products seek to fulfill customer needs, an internal marketing perspective holds that, to effectively sustain employees’ investment of time, energy, and ego, a job-product needs to include attribute bundles that cater to the diverse range of employee needs.

Research on psychological contracts suggests that employees’ job needs are often multi-faceted. Rooted in social exchange theory, psychological contract refers to an employee’s perception of the unwritten promises and obligations implicit in his/her relationship with the employing organization (Rousseau and McLean Parks 1993; Thompson and Bunderson 2003). Fulfillment of psychological contract enhances employee job satisfaction and employee retention, whereas a breach or violation of psychological contract leads to undesirable outcomes such as intention to quit and actual turnover (Bunderson 2001; Robinson and Morrison 2000). Employees’ psychological contracts are typically multi-dimensional, including economic, developmental, and ideological facets (Robinson et al. 1994; Thompson and Bunderson 2003). The economic facet of psychological contract is more transactional and short-term oriented, often including issues such as the employing organization’s provision of adequate compensation, benefits, and a safe working environment. The developmental facet of psychological contract is more relational and long-term oriented, involving issues such as the organization’s provision of training and professional development. The increasingly competitive and turbulent job markets nowadays dictate that continuous learning and development is a key part of employees’ continuing career success. Consequently, employee professional development has become a critical part of employee job needs (Maurer et al. 2002).

A third dimension of psychological contract is the ideological facet, which mainly refers to organizational responsibility to advance social well-being and provide opportunities for employees to participate in the organization’s societal citizenship behavior (Blau 1964; Thompson and Bunderson 2003). Organizational championship of important social causes can be effective inducements to motivate employee contribution and commitment because “helping to advance cherished ideals is intrinsically rewarding” (Blau 1964, p. 239). Research on social identity (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003; Dutton et al. 1994) also provides some indirect support for the importance of ideological job needs; employees desire to work for organizations that have good values and a positive image, which help satisfy their higher order self-definitional needs (i.e., “Who am I?”).

Heterogeneity in Multi-faceted Job Needs and Demand for CSR

We expect employees to differ in terms of their economic, developmental, and ideological job needs. The internal marketing perspective emphasizes individual differences in employees’ job needs and calls for a segmented approach when designing job-products (Bhattacharya et al. 2008). Similarly, the psychological contract literature suggests that employee perceptions of organizational responsibilities are personal, self-constructed, and idiosyncratic (Raja et al. 2004). Differences in individual personality, gender, and cultural values (e.g., humane orientation, institutional collectivism) have been shown to correlate with different employee expectations of organizational obligations (Mueller et al. 2012; Raja et al. 2004).

Supporting heterogeneity in employees’ multi-faceted job needs, research on individuals’ relations to their work (Wrzesniewski et al. 1997) has identified three types of orientations toward work: those viewing work as a job, a career, or a calling. Individuals with a “job” orientation view work primarily as an opportunity for economic rewards. Individuals with a “career” orientation have a deeper personal investment in their work, and value opportunities for professional growth and advancement. Individuals with a “calling” orientation, on the other hand, seek work as an expression of self and focus on pursuing something that is principle-based, transcending self-interest. Due to their focus on values, identity expression, and societal well-being, employees with a “calling” orientation will likely put greater importance on ideological needs relative to those with a “job” or “career” orientation. Similarly, those with a “career” orientation will likely place greater importance on developmental needs than employees with other orientations.

We expect employee heterogeneity in job needs to be reflected in their differential demand for organizational CSR programs. Prior research suggests that employees vary in their support of and receptivity to organizational engagement in CSR. Specifically, Rodrigo and Arenas (2008)’s qualitative study reveals a typology of employees based on their attitude toward CSR: committed, indifferent, and dissident employees. Committed employees are concerned about social welfare and receive their organizations’ CSR practices with great enthusiasm; indifferent employees focus on their own career and are indifferent about whether their organizations engage in CSR or not; and dissident employees are frustrated about their organizations’ spending money on CSR.

However, little is known about why employees differ in their attitude toward, or demand for, organizational CSR programs. We build upon Rodrigo and Arenas (2008)’s qualitative work to examine psychological correlates of employees’ differential demand for organizational CSR. Specifically, since CSR represents an organization’s actions that intend to further some social good beyond the interests of the firm, employees higher in ideological needs will naturally put more importance on their organizations’ CSR. In addition, CSR has increasingly become an integral part of an organization’s daily operation and strategic planning, and as a result, employees often perform CSR-related responsibilities on their job (Mirvis 2012; Surroca et al. 2010). As Mirvis (2012, p. 94) points out, “… more employees today are engaged in sustainable supply chain management, cause-related marketing, and green business initiatives – in effect, doing social responsibility on-the-job.” Accordingly, employees with higher developmental needs will likely demand their organizations to engage in more CSR activities. Therefore, we hypothesize,

H1

There exists significant heterogeneity in employees’ multi-faceted job needs (economic, developmental, and ideological).

H2

All else equal, employees’ demand for organizational CSR programs is positively associated with (a) importance of ideological job needs, and (b) importance of developmental job needs.

CSR and Fulfillment of Multi-faceted Job Needs

CSR programs comprise various strategies and operating practices that contribute to the long-term economic, social, and environmental well-being (Kotler and Lee 2005). CSR activities reveal the values and principles of an organization (Brown and Dacin 1997; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001), portraying it as a good citizen and a contributor to society rather than as an entity concerned solely with maximizing profits. Socially responsible organizations uphold the socio-cultural norms in their institutional environment and honor “the social contract” between business and society (Scott 1987). As such, organization’s CSR programs help fulfill employees’ ideological needs of pursuing/championing social causes and making a difference.

Interestingly, recent research also suggests that CSR programs may help fulfill employees’ developmental needs (Bhattacharya et al. 2008; Mirvis 2012; Porter and Kramer 2011). When employees participate in CSR projects that involve tasks outside of their daily routine, they learn specific skills that can help them advance in their careers. For example, through its breakthrough citizenship initiative, the Corporate Service Corp, IBM sends its top employees to volunteer in local communities around the globe (e.g., emerging markets and less developed regions), contributing their expertise, technology, and creativity to solving various social and developmental issues. In the process, IBM employees have significantly increased their cultural intelligence and resilience as leaders, honed their problem-solving skills, and gained valuable insights into global markets (CSRwire 2009, 2013).

As more and more organizations integrate socially responsible programs into their core business strategy (e.g., sustainable supply chain, green business initiatives, products targeting economically and socially disadvantaged; Kotler and Lee 2005; Porter and Kramer 2011), employees are increasingly required to engage in CSR activities on the job. Surroca et al. (2010) find that CSR contributes to the accumulation of human capital because adoption of CSR strategies leads to employees’ active involvement in improving the organization’s environmental and social performance. Consequently, CSR initiatives open up much needed opportunities for empowering employees to affect change, and to hone essential business skills such as leadership, problem-solving, and out-of-box innovative thinking (Kanter 2009). Therefore,

H3

All else equal, organizations that are viewed more favorably for their CSR initiatives are better at the fulfillment of employee (a) ideological job needs, and (b) developmental job needs.

Mediating Role of Job Needs Fulfillment in the CSR—Employee Outcome Link

Prior research has demonstrated that CSR can generate a range of positive employee outcomes such as organizational commitment (Brammer et al. 2007), job satisfaction (Herrbach and Mignonac 2004; Valentine and Fleischman 2008), and loyalty (Bhattacharya et al. 2008, 2011). Bhattacharya et al. (2011) argue that CSR programs need to fulfill key stakeholder needs to trigger favorable stakeholder reactions. In the context of consumer reactions to CSR, Du et al. (2008) find that provision of functional and psychosocial benefits is a key route through which CSR programs enhance customer loyalty.

Drawing upon this line of research as well as the literature on internal marketing, we contend that the fulfillment of employees’ multi-faceted job needs is the essential route through which CSR generates positive employee-related outcomes. CSR broadens the attribute bundle of “job-products” that an organization can offer to its employees and constitutes a meaningful and valuable job attribute, because it can produce self-relevant benefits for employees. An organization’s CSR is capable of catering to its employees’ higher-level, ideological needs (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003) as well as professional developmental needs (Mirvis 2012; Surroca et al. 2010). In turn, better fulfillment of ideological and developmental needs leads to favorable employee-related outcomes such as job satisfaction and loyalty. On the other hand, if organization’s CSR programs, due to ineffective design or implementation (e.g., poor fit between CSR and the organization, lack of employee awareness), do not fulfill its employees’ needs, then the link between CSR and positive employee outcomes is likely to be muted. In short, we expect the fulfillment of ideological and developmental job needs to mediate the link between CSR and employee outcomes.

H4

All else equal, organizations that are viewed more favorably for their CSR initiatives enjoy more favorable employee outcomes, and these positive relationships are mediated by the fulfillment of employee (a) ideological job needs, and (b) developmental job needs.

Moderating Role of CSR Proximity in the CSR—Employee Outcome Link

We also investigate the role of CSR proximity in the CSR—employee outcome link. CSR proximity refers to the extent to which employees know about and/or are actively involved in their organizations’ CSR (Dawkins 2004; Du et al. 2011). Despite being the internal stakeholders of an organization, employees often exhibit surprisingly low levels of proximity to their organizations’ CSR activities, in terms of both CSR awareness and CSR engagement (Bhattacharya et al. 2008; Dawkins 2004). Since awareness of CSR is a prerequisite for any positive reactions to occur, employees’ lack of CSR knowledge remains a major challenge for organizations in their attempts to garner positive outcomes from this stakeholder group.

Furthermore, employees, particularly those looking to fulfill their job needs through CSR, not only demand to be informed, but they also want to be part of their organizations’ CSR programs effecting positive change (Cone 2008). Beyond CSR knowledge, employees’ active involvement or participation in the organization’s CSR activities greatly increases their proximity to social causes and allows employees to be enactors and enablers of CSR programs, rather than being mere observers. Employees who have deep knowledge about their organizations’ CSR and who are actively involved in creating, supporting and implementing CSR initiatives are likely to be more satisfied with their job and be more loyal to their organizations. Overall, we expect CSR proximity to magnify the power of CSR in generating positive employee outcomes.

H5

CSR proximity moderates the relationships between CSR and employee outcomes, such that the relationships are stronger when CSR proximity is high.

Mediating Role of Job Needs Fulfillment in the Moderated Relationships

Finally, as we have argued, a key mechanism through which CSR generates positive employee outcomes is employee job needs fulfillment. Thus, it is conceivable that, for employees with high CSR proximity, organizational CSR will enhance employee job needs fulfillment to a greater extent, which then generates more positive employee outcomes (Bhattacharya et al. 2008; Mirvis 2012). Employees proximal to their organizational CSR will be more likely to have a sense of accomplishment, learn new skills, and contribute to the greater good, all of which lead to better fulfillment of ideological and developmental job needs and subsequently result in greater employee satisfaction and loyalty.

On the contrary, for employees with lower CSR proximity (i.e., unaware of and/or not engaged in their organizations’ CSR activities), CSR actions are less likely to fulfill their ideological or developmental job needs. As a result, these CSR actions may relate little to job satisfaction or loyalty for employees with low levels of CSR proximity.

H6

The moderated relationships among CSR, CSR proximity, and employee outcomes are mediated by the fulfillment of (a) ideological job needs, and (b) developmental job needs.

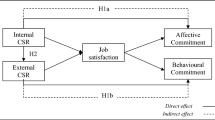

Figure 1 presents our conceptual framework. Prior research has shown that, in addition to CSR, another key dimension of organizational perceptions is organizational competency (Brown and Dacin 1997; Du et al. 2007), which can affect employee job needs fulfillment and subsequent outcomes. Consequently, we include organizational competency (i.e., the organization’s ability to deliver superior performance) as a control variable.

Method

Sample and Procedures

We collected data in a large national leadership conference for professional women. Our respondents were drawn from conference attendees, who are professional women from a wide range of industries as well as varying professional backgrounds.

We use a women-only sample to test our hypotheses for two reasons. First, prior research has documented a gender effect in terms of values, job needs, and demand for CSR (e.g., Brammer et al. 2007; Ramamoorthy and Flood 2004). For example, relative to men, women care more about societal and environmental well-being (Schwartz and Rubel 2005), and care more about procedural justice (i.e., perceived fairness of the means used to make decisions; Sweeney and McFarlin 1997; Ramamoorthy and Flood 2004). Further, when choosing a job, women place more importance than men on an organization’s CSR and consider “the potential to make a contribution to society” a more important criterion (Brammer et al. 2007). Since one of our key research questions is to uncover the mechanisms for the impact of CSR on employee-related outcomes (i.e., through fulfilling important job needs), a sample consisting of women who place higher importance on CSR seems appropriate for an initial test of our theory. At the same time, with respect to our other research question that investigates heterogeneity in employee job needs and demand for CSR (i.e., H1 and H2), a women-only sample comprises a more conservative test of our predictions, because it is hard to find heterogeneity among a relatively homogenous, female-only sample relative to a mixed gender sample.

The survey was announced by the organizer of the leadership conference, a private academic institution located in a large U.S city. A dozen of computer stations dedicated to the survey study were placed in the lobby of the conference venue, with a link to the survey displayed prominently on the computer homepage. Conference attendees were encouraged and reminded to take the survey during session breaks and were assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses.

A total of 353 women employees filled out the survey at the conference. After deleting data with missing values on key variables, we got a final sample of 322. Among our respondents, 58.4 % are between ages 31 and 50, and 27.9 % are 51 or older. 29.5 % of our respondents have a Bachelor’s degree, and 60.3 % have a Master’s degree or some graduate school. 55.3 % have personal gross income of $100,000 or higher, and 55.6 % have been with their current organizations for 6 years or longer. We first included all demographic variables in our analysis: only age was significant in some of the analytic results, while all other demographic variables were nonsignificant across all analysis. Thus, we only present our analysis with age as a covariate.

Measures

Since this survey was administered during the breaks of a leadership conference, we had to employ short (e.g., single-item, two-item, and three-item) measures to keep the survey brief and to reduce respondent fatigue and/or impatience. Importantly, though, recent research comparing the predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs shows that when the object is concrete and familiar, single-item measures are equally effective and more efficient (Bergkvist and Rossiter 2007). Thus, on balance, single-item or other short measures for familiar constructs such as job satisfaction and economic job need fulfillment seemed both necessary and appropriate. To minimize demand effects, we first asked questions relating to employee outcomes, then questions relating to employee multi-faceted job needs, followed by questions on employee perceptions of CSR and organizational competency, as well as those on CSR demand and CSR proximity. Please refer to Appendix for details on all the key measures.

Employee Outcomes

We examine two employee-related outcomes, job satisfaction, and turnover intention. Job satisfaction is a key employee outcome (e.g., Janssen and van Yperen 2004) and is measured by a single-item, “I am satisfied with my present job” (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Employee retention is critical in preserving organization’s human resources. We measure employees’ turnover intention by two items “I do not plan to work with this organization much longer,” and “If given the opportunity, I would seek employment with another organization.” The correlation between the two items is .65.

Multi-faceted Job Needs

We measure three types of job needs: economic, developmental, and ideological needs. The economic need is captured by a single-item on compensation package. The developmental need is captured by two items on opportunities to develop skills/expertise and opportunities for career advancement (Maurer et al. 2002). The ideological need is measured by two items on “making a positive impact on society,” and “opportunities to express and act in line with values” (Bhattacharya et al. 2008; Thompson and Bunderson 2003). To assess individual differences in terms of job needs, we measure the perceived importance of economic, developmental, and ideological needs, respectively (1 = very unimportant, 7 = very important). To assess fulfillment of employee job needs, we measure how well an organization fulfills these different facets of job needs (1 = not at all, 5 = to a great extent).

Demand for Organizational CSR

To assess employees’ demand for organizational CSR in the workplace, we have two separate measures. One item assesses employees’ belief as to how important it is that an organization engages in CSR (Sen et al. 2009). Another item asks employees “how much of your current salary would you be willing to give up to help make your organization ideal in terms of being socially responsible? (0 %, 5 % or less, and 6 % or higher).”

CSR

Our measure for CSR is based on prior research (Du et al. 2007; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001). Since organizational commitment to CSR is a critical aspect of CSR (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003; Du et al. 2007; Kotler and Lee 2005), we have an overall item for CSR and two items assessing CSR commitment (Cronbach’s alpha = .90).

CSR Proximity

For CSR proximity, we include two items assessing employees’ knowledge about and involvement in their organizations’ CSR programs. CSR knowledge taps into employees’ level of awareness and familiarity with their organizations’ CSR programs and CSR involvement gages employees’ direct participation in CSR programs (Du et al. 2011; Dawkins 2004). These two items are correlated at r = .61.

Organizational Competency

In line with prior CSR research (e.g., Brown and Dacin 1997; Du et al. 2007), we include organizational competency as a control for our regression analysis. Organizational competency is measured by three items (Cronbach’s alpha = .74).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Measurement

The confirmatory factor analysis of our measures indicates that the overall fit of the measurement model is satisfactory: Chi square(68) = 140.50 (p < .01); the root mean square residual (RMR) = .03; the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .06; the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) = .94; the comparative fit index (CFI) = .97, the non-normed fit index (NNFI) = .94 and the normed fit index (NFI) = .94. Furthermore, all indicators load significantly on their hypothesized latent construct, demonstrating convergent validity. Average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct exceeds .50 and is larger than the square of any inter-construct correlation, thereby demonstrating discriminant validity of the measurement model (Hair et al. 1998).

Common Method Bias

Because we relied on a single source for our measures, common method bias in self-reported measures could be a concern. Employing the widely used Harman’s one-factor method (e.g., Carr and Kaynak 2007; Podsakoff and Organ 1986), we ran a factor analysis of all measures to examine the likelihood of a single or dominant factor. The unrotated solution showed no evidence of a dominant common factor (six factors had eigenvalues greater than 1.0; the first factor accounted for 28 % of the total variance). Thus, common method bias does not seem to represent a serious issue for this study.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations for the key constructs. Table 2 provides a summary of findings based on the hypothesis tests. Consistent with our expectations, our cluster analysis uncovers three employee segments, Idealists, Enthusiasts, and Indifferents, who vary significantly in their multi-faceted job needs and consequently their demand for CSR. Furthermore, our findings indicate that fulfillment of ideological and developmental job needs mediates the relationships between organizational CSR and job satisfaction and turnover intention. Finally, the positive effects of CSR on these employee-related outcomes are stronger for employees with higher CSR proximity. We discuss these results in detail next.

Employee Heterogeneity in Multi-faceted Job Needs and Demand for CSR

To test H1, we ran cluster analysis to uncover different employee segments based on variations in their multi-faceted job needs. Cluster analysis has been widely employed in marketing to identify consumer segments that share common characteristics within, and differences across, groups (Punj and Stewart 1993). Since cluster analysis makes no prior assumptions about differences in the sample, it is an appropriate method to tackle under-theorized issues such as employee heterogeneity in multi-faced job needs and demand for CSR (Aldenderfer and Blashfield 1984; Mair et al. 2012).

To run a cluster analysis, one needs to (1) select a set of attributes that will be included in the analysis, (2) use an appropriate clustering method to create the optimal number of clusters, and (3) validate the cluster results or solutions (Aldenderfer and Blashfield 1984; Ketchen and Shook 1996). We use the three dimensions of employee job needs (economic, developmental, and ideological) on which to run the cluster analysis. In line with prior research (Ketchen and Shook 1996), we employ a two-stage clustering method. First, we performed a hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s method to select the appropriate number of clusters and obtain the estimated centroids. We derive a three cluster solution, based on the increase in the average within-cluster distance criterion and the profile of the cluster centers identified (Aldenderfer and Blashfield 1984). These results are then used in the second step, a K-means non-hierarchical clustering method, which fine-tunes the clustering results. Table 3 presents the cluster analysis results. Based on the cluster profiles, we label cluster 1 as “Idealists,” who consider all three dimensions of job needs to be highly important, and label cluster 2 as “Enthusiasts,” who place more importance on developmental and ideological needs, but less importance on economic needs. Cluster 3 is labeled as “Indifferents,” who place more importance on economic and developmental needs, but less importance on ideological needs.

To check the validity of our cluster results, we performed ANOVA and Chi square tests to examine cluster-wise differences. Employee differences in multi-faceted job needs are expected to relate to differences in their demand for CSR. As expected, these three clusters, or segments, of employees differ significantly in their demand for CSR. Specifically, the Idealists’ cluster has the highest CSR demand, as measure by perceived CSR importance (M = 4.35), the Enthusiasts’ cluster has the second highest CSR demand (CSR importance: M = 4.16), and the Indifferents’ cluster has the lowest CSR demand (CSR importance: M = 3.89). The cluster-wise difference is significant (F (2, 319) = 10.88, p < .01). Regarding another measure for CSR demand, employees’ willingness to trade off salary for CSR, the Enthusiasts’ cluster has more people willing to trade off more of their salary for CSR (28.3 % willing to trade off more than 5 % of their salary, 52.8 % willing to trade off 5 % or less), followed by the Idealists’ cluster (20.4 % willing to trade off more than 5 % of their salary, 59.3 % willing to trade off 5 % or less), with the Indifferents’ cluster least willing to trade off their salary for CSR (only 4.5 % willing to trade off more than 5 % of their salary, and 59.1 % willing to trade of 5 % or less). The Chi square test for group difference is significant (Chi square = 18.66, p < .01). These cluster-wise differences lend support to the validity of the derived clusters (Aldenderfer and Blashfield 1984). Thus, H1 is supported by our cluster analysis, in the sense that there exists significant employee heterogeneity (as indicated by three distinct clusters) in their multi-faceted job needs.

To test H2, we examine two dependent variables that measure employee demand for CSR: perceived importance of CSR and willingness for salary—CSR tradeoff. We first ran ordinary least square (OLS) regression with perceived importance of CSR as the dependent variable, and importance of economic, developmental, and ideological job needs and employee age as the independent variables. Table 4 presents the regression results. As expected, importance of ideological job needs is positively associated with CSR importance (b = .33, p < .01), supporting H2(a). However, developmental job needs are not associated with CSR importance (b = −.00, NS), failing to provide support for H2(b).

Additionally, we examine another measure of employee demand for CSR: willingness to trade off salary for CSR (i.e., salary-CSR tradeoff). Since this variable is ordinal, we ran a probit regression. As can be seen from the results in Table 4, importance of ideological job needs is positively associated with willingness to trade off salary for CSR (b = .26, p < .01), supporting H2 (a). However, importance of developmental job needs are not associated with willingness to trade off salary for CSR, failing to provide support for H2(b), although the coefficient for the importance of developmental job needs has the expected positive sign and approaches the significance level of .10 (b = .15, p = .12). Additionally, as expected, importance of economic job needs is negatively associated with willingness to trade off salary for CSR (b = −.21, p < .01). In sum, H2(a) is supported, but H2(b) is not supported.

CSR, Fulfillment of Job Needs, and Employee Outcomes

We tested hypotheses 3–6 using multiple regressions with relevant interaction terms. To enhance the interpretation of the regression coefficients in moderated regression models, we mean-centered all continuous independent variables (Aiken and West 1991).

CSR and Fulfillment of Job Needs

To test H3, we ran regression models with fulfillment of ideological and developmental job needs as the dependent variables, respectively, and CSR, CSR proximity, CSR x CSR proximity, organizational competency, and age as the independent variables. Table 5 presents the regression results. H3 predicts that CSR will be positively related to fulfillment of ideological and developmental needs. As expected, the coefficient of CSR in the ideological job needs fulfillment model is .47 (p < .01), and the coefficient of CSR in the developmental job needs fulfillment model is .23 (p < .01). Thus, H3 is fully supported. Additionally, we regressed fulfillment of economic job needs on the same set of independent variables and found that CSR is not associated with fulfillment of economic job needs fulfillment.

Mediating Role of Job Needs Fulfillment in the CSR—Employee Outcome Link

To test H4 the mediating roles of ideological and developmental job needs fulfillment in the CSR—employee outcome link, we use Preacher and Hayes (2008)’s bootstrap test of the indirect effect. Specifically, according to Zhao et al. (2010)’s procedure for testing mediation analysis, we regressed ideological (developmental) job needs fulfillment on CSR, CSR proximity, CSR × CSR proximity, organizational competency, and age, which provides coefficient a (i.e., the coefficient of independent variable → mediator variable: CSR → ideological/developmental job needs fulfillment). We also regressed employee outcomes (i.e., job satisfaction and turnover intention) on CSR, ideological job needs fulfillment, developmental job needs fulfillment, CSR proximity, CSR × CSR proximity, organizational competency, and age, which provide coefficient b (i.e., the coefficient of mediator → dependent variable: ideological/developmental job needs fulfillment → employee outcomes). We used 5,000 bootstrap samples and estimated a, b, and a x b for each sample. Indirect effect is calculated as the mean of all a x b estimates, and the 95 % confidence interval is based on the empirical distribution of a x b estimates. If a x b is significant, then the mediating role of ideological/developmental job needs fulfillment in the CSR → employee outcome link is significant.

Regarding the mediating role of ideological job needs fulfillment in the CSR → employee outcome link, in the case of job satisfaction, the Preacher and Hayes (2008)’s bootstrap analysis, using 5,000 bootstrap samples, shows that a x b is positive and significant (a x b = .091), with a 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval excluding zero (.019 to .176). This suggests that the mediating role of ideological job needs fulfillment in the CSR → job satisfaction link is significant at p < .05. In the case of turnover intention, the bootstrap analysis, using 5,000 bootstrap samples, shows that a x b is negative and significant (a x b = −.086), with a 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval excluding zero (−.168 to −.016). This suggests that the mediating role of ideological job needs fulfillment in the CSR → turnover intention link is significant at p < .05. Taken together, H4 (a) is supported.

Regarding the mediating role of developmental job needs fulfillment in the CSR → employee outcome link, in the case of job satisfaction, the bootstrap analysis shows that a x b is positive and significant (a x b = .091), with a 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval excluding zero (.034 to .177). This suggests that the mediating role of developmental job needs fulfillment in the CSR → job satisfaction link is significant at p < .05. In the case of turnover intention, the bootstrap analysis shows that a x b is negative and significant (a x b = −.065), with a 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval excluding zero (−.132 to −.025). This suggests that the mediating role of developmental job needs fulfillment in the CSR → turnover intention is significant at p < .05. In sum, H4 (b) is also fully supported.

Additionally, when both mediators, ideological and developmental job needs fulfillment, are included in the regression, neither the direct effect of CSR on job satisfaction (c = .09, NS) nor the direct effect of CSR on turnover intention (c = −.09, NS) is significant, indicating that this is indirect only mediation (Zhao et al. 2010).

Moderating Role of CSR Proximity in the CSR—Employee Outcome Link

H5 predicts that CSR proximity will enhance the relationship between CSR and employee outcomes (i.e., job satisfaction and turnover intention). As expected, in the case of job satisfaction (Table 5, job satisfaction model (1), the coefficient of CSR × CSR proximity interaction is positive (b = .14, p < .05), suggesting that the relationship between CSR and employee job satisfaction becomes more positive as CSR proximity increases. In the case of turnover intention (Table 5, turnover intention model (1), the coefficient of CSR × CSR proximity is negative (b = −.17, p < .01), suggesting that CSR will reduce employees’ turnover intention to a greater extent when CSR proximity is higher. Thus, H5 is fully supported.

Mediating Role of Job Needs Fulfillment in the Moderated Relationships

To test H6, the mediating role of job needs fulfillment in the moderated relationships among CSR, CSR proximity, and employee outcomes, we use Preacher and Hayes (2008)’s bootstrap analysis of the indirect effect a x b. Regarding the mediating effect of ideological job needs fulfillment in the CSR × CSR proximity → employee outcome link, in the case of job satisfaction, the bootstrap analysis, using 5,000 bootstrap samples, shows that a x b is positive and significant (a x b = .021), with a 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval excluding zero (.0019 to .061). This suggests that the mediating effect of ideological job needs fulfillment in the CSR × CSR proximity → job satisfaction link is significant at p < .05. In the case of turnover intention, a x b is negative and significant (a x b = −.020), with a 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval excluding zero (−.058 to −.001). This suggests that the mediating effect of ideological job needs fulfillment in the CSR × CSR proximity → turnover intention is significant at p < .05. In short, H6(a) is fully supported.

Regarding the mediating effect of developmental job needs in the CSR × CSR proximity → employee outcome link, in the case of job satisfaction, the bootstrap analysis reveals that a x b is not significant (a x b = .0403), with a 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval including zero (−.0007 to .0925). This indicates that the mediating effect of developmental job needs in the CSR × CSR proximity → job satisfaction link is not significant. In the case of turnover intention, a x b is negative and significant (a x b = −.033), with a 95 % bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval excluding zero (−.075 to −.0057), suggesting that the mediating effect of developmental job needs fulfillment in the CSR × CSR proximity → turnover intention link is significant at p < .05. In other words, H6(b) is supported in the case of turnover intention but not in the case of job satisfaction.

Additionally, when both mediators, ideological and developmental job needs fulfillment, are included in the regression analysis, neither the direct effect of CSR × CSR proximity on job satisfaction (c = .06, NS) nor the direct effect of CSR × CSR proximity on turnover intention (c = −.11, NS) is significant at p = .05, suggesting that this is indirect only mediation.

Discussion

CSR is a matter of strategic importance due to its potential positive impact on firm financial performance and long-term competitive advantage. This research advances our understanding of employee heterogeneity in the demand for organizational CSR and the underlying mechanisms linking CSR to positive employee-related outcomes. Our findings have important implications for CSR theory and practice.

Theoretical Implications

The resource-based view of the firm contends that intangible, firm-specific resources are the basis of a firm’s competitive advantage and long-term financial performance (Barney 1991). In particular, human capital is one of the most important intangible assets, because competent and motivated employees are the essential drivers of long-term organizational growth. Prior literature suggests that CSR can contribute to firm financial performance by cultivating essential intangible resources (e.g., Branco and Rodrigues 2006; Surroca et al. 2010). Our study advances our current understanding on how CSR cultivates human capital and contributes to organizational performance in several ways.

First, we extend the CSR literature on employees by documenting significant employee heterogeneity in their demand for organizational CSR programs, an issue largely ignored in prior investigations. Through cluster analysis, we identify three heterogeneous employee segments, Idealists, Enthusiasts, and Indifferents, who differ in their multi-faceted job needs. Further, we show that these three segments also vary significantly in their demand for organizational CSR programs. In particular, we find that employees’ ideological job needs, but not their economic or developmental job needs, are positive correlates of their demand for CSR. This finding suggests that, similar to consumers, employees vary in their support of and receptivity to organizational engagement in CSR.

Second, our research sheds new light on the mechanisms linking CSR and employee outcomes. Our findings show that by engaging in CSR, an organization can better fulfill its employees’ ideological and developmental job needs and thereby enhance employees’ job satisfaction and reduce their turnover intention. Unlike prior research that draws primarily on social identity theory to explain positive employee reactions to CSR (e.g., Kim et al. 2010), we adopt novel, complementary conceptual lenses (i.e., internal marketing theory and psychological contract theory) to examine how employees react to CSR. Our study shows that internal marketing theory and, more specifically, the conceptualization of a job as a multi-faceted product comprise a novel and fruitful approach to investigate employee reactions to CSR. Future research should continue to adopt an interdisciplinary approach and apply relevant marketing theories (e.g., customer orientation, customer segmentation) to study CSR—employee linkages (Du et al. 2011).

One interesting and important finding from our study is that CSR leads to better fulfillment of not only employee ideological needs but also employee developmental job needs. As CSR increasingly moves from the periphery to the center of business strategy (Porter and Kramer 2011), engagement in CSR can be developmental and transformative for the employees (Mirvis 2012; Surroca et al. 2010). While prior research has shown that CSR can contribute to human capital by enhancing employee satisfaction and loyalty (e.g., Valentine and Fleischman 2008), the positive impact of CSR on the fulfillment of employee developmental needs suggests that an organization’s CSR can be a powerful vehicle to build more competent and productive employees. It would be highly worthwhile to investigate the relationship between CSR and employee competency, such as leadership development, expertise, innovativeness, and productivity.

Last but not least, our study highlights the importance of CSR proximity in maximizing returns to CSR. Despite being the key internal stakeholders of an organization, prior research has shown that employees are often unaware of, or uninvolved in their organizations’ CSR activities (Bhattacharya et al. 2008; Dawkins 2004). Our findings reinforce earlier research by showing that low CSR proximity is indeed a stumbling block for organizations seeking to reap employee-related benefits from CSR. Organizations will reap greater employee-related benefits (i.e., better fulfillment of employees’ ideological and developmental job needs, higher job satisfaction, and lower turnover intention) when CSR proximity is higher. Organizations should find ways to more effectively communicate their CSR to employees and find more ways to engage their employees.

Practical Implications

The accumulation of human capital is a key source of competitive advantage. Our research offers several important implications for managers seeking to cultivate their firms’ human resources through CSR programs. In a conceptual framework accounting for the contingent link between CSR performance and financial performance from a consumer perspective, Schuler and Cording (2006) identify moral values (a consumer-specific factor) and information intensity (a firm-specific factor) as critical factors that influence the strength of the CSR—financial performance link. Similarly, our study suggests that, in the employee realm, managers should pay attention to both employee-specific and firm-specific factors when designing and implementing CSR activities, as well as when assessing the employee-related business outcomes of CSR.

Employees have heterogeneous job-related needs and varying demand for organizational CSR. When designing and implementing CSR programs, organizations should not assume “one size fits all,” but rather should adopt a segmented approach, tailoring their CSR offerings according to employees’ individual needs. To better tailor CSR programs to the needs of employees, organizations should first have a good understanding of their employees. We recommend that organizations should conduct their own cluster analysis on their employees and identify the idealist, enthusiastic, and indifferent clusters. Such analyses would greatly facilitate a more strategic approach to CSR programs.

Further, our findings highlight the important role of CSR proximity in accentuating the positive impact of CSR on employees. Although CSR proximity can amplify the business returns to CSR, our study shows that, in general, CSR proximity among employees is low (i.e., mean = 3.15 on a 5-point scale). Managers should place high importance on raising CSR awareness and level of CSR engagement among employees. In line with Bhattacharya et al. (2008), our results suggest that rather than a top-down, add-on approach to CSR, organizations should involve their employees in the planning, design, and implementation of CSR programs, making them co-producers and enactors of social responsibility programs. In addition, communicating CSR programs to employees is also critical. As suggested by prior research (e.g., Dawkins 2004) and confirmed in our survey, despite being the internal stakeholder of a firm, employees’ awareness of firm CSR tends to be low. Managers should explore and utilize various communication channels to inform their employees of firm CSR activities, such as the organizational intranet, newsletters, emails, screen displays in organizational buildings, announcements in regular work meetings, and so on. Relatedly, managers should also adopt a segmented approach when communicating CSR to their employees, highlighting different benefits of CSR to different employee segments. For example, emphasizing how CSR enhances the fulfillment of developmental job needs would be a useful message to engage the segment of Indifferents, who value developmental needs but care less about ideological needs.

Finally, managers should realize that CSR can satisfy not only employee ideological job needs, but also employee developmental job needs. This would lead to a deeper appreciation of how CSR would help cultivate a firm’s human resources (Branco and Rodrigues 2006). Rather than treating CSR as add-on, public relations strategy, managers should mindfully embed CSR programs in the core business strategy and use CSR programs as important platforms to train and develop their employees. Through more effective fulfillment of both ideological and developmental job needs, CSR programs can better cultivate human capital and contribute to long-term competitive advantage.

Limitations and Future Research

This research is subject to several limitations. First, despite the justifications we have for using a female-only sample, such a single gender sample reduces the external validity of our findings. Replications and extensions of our findings using a mixed gender sample will increase the generalizability of our findings. Second, we use a field survey methodology and single-informant technique; such an approach might suffer from common method bias and social desirability bias. Although our analysis shows that common method bias does not seem to be a serious concern in our study, future research could utilize other methodologies (e.g., experiment, secondary data sources) to further collaborate our findings. For example, one can get CSR performance ratings from the Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini & Co. (KLD) dataset, a widely used dataset for CSR (e.g., Godfrey et al. 2009), and link CSR performance to survey-based employee perceptions and behaviors. Use of secondary data sources on CSR will also minimize biases due to socially desirable responding. Additionally, future research should use structural equation modeling to validate our framework and simultaneously test all relationships.

Third, we employed various short measures (e.g., single-item, two-item, and three-item) in our study. Although our confirmatory factor analysis results indicate a satisfactory measurement model, some of the constructs might have been better measured using multiple, more comprehensive list of items. Lastly, future research should go beyond a U.S. only sample to explore CSR—employee relationships in different cultures (e.g., individualistic vs. collectivistic) and different economic development stages (e.g., developed vs. emerging or developing economies). CSR practices and strategies are often different in developing countries with weak institutional environments and abundant social issues (Dobers and Halme 2009), as well as generating dissimilar organizational outcomes (Lindgreen et al. 2010). Thus, we call for future research to investigate whether and to what extent our framework generalizes to emerging or developing countries.

More generally, our work opens up several important avenues for future research. First, regarding heterogeneity in employee demand for CSR, we identify three distinct segments and show that perceived importance of ideological job needs is a key psychological correlate. Future research might dig deeper into factors underlying differential employee demand for CSR. For instance, one can explore the relationship between employees’ basic values and their demand for CSR. Schwartz (1992) identifies 10 motivationally distinct basic values: power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, and security. Future research can explore how these values are correlated with employees’ multi-faceted job needs and consequently their demand for CSR. One might expect that universalism and benevolence are correlated with ideological job needs, and power, achievement, stimulation, and security are correlated with developmental job needs. Relatedly, researchers can take a dynamic view of employee job needs and demand for CSR, and explore how employees’ attitude toward and demand for CSR might evolve as they move up along the corporate ladder.

Second, CSR programs occur in different stakeholder domains (e.g., employees, consumers, investors, environment, local communities; Freeman et al. 2007) and take on different formats (e.g., philanthropy, employee volunteering, and socially responsible practices; Kotler and Lee 2005). Future research can take a finer-grained approach by breaking down an organization’s CSR programs into different domains or categories, and examine how different types of CSR might generate different employee-related outcomes. It would be interesting to compare and contrast CSR programs such as ethics training (Valentine and Fleischman 2008), employee volunteering, and environmentally friendly sourcing and manufacturing initiatives (Porter and Kramer 2011), in terms of their differential impact on fulfilling employee ideological and developmental job needs. Such research would provide valuable insights to managers seeking to build intangible resources from a portfolio of CSR activities.

References

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the s back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 836–863.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Aldenderfer, M. S., & Blashfield, R. K. (1984). Cluster analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39.

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. R. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(2), 175–184.

Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1992). Services marketing starts from within. Marketing Management, 1(1), 24–34.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2003). Consumer-company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 76–88.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Sen, S., & Korschun, D. (2008). Using corporate social responsibility to win the war for talent. MIT Sloan Management Review, 49(2), 37–44.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Sen, S., & Korschun, D. (2011). Leveraging corporate responsibility: The stakeholder route to maximizing business and social value. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: Wiley.

Bonini, S., Koller, T. M., & Mirvis, P. (2009). Valuing social responsibility programs. McKinsey on Finance, 32(Summer), 11–18.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(10), 1701–1719.

Branco, M. C., & Rodrigues, L. L. (2006). Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics, 69(2), 111–132.

Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68–84.

Bunderson, J. S. (2001). How work ideologies shape the psychological contracts of professional employees: Doctors’ responses to perceived breach. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 717–741.

Carr, A., & Kaynak, H. (2007). Communication methods, information sharing, supplier development and performance. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 27, 346–370.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. The Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Cone. (2008). Past. Present. Future. The 25th anniversary of cause marketing. http://www.coneinc.com/content1187. Accessed 15 March 2013.

CSRWire. (2009). IBM expands corporate service corps in emerging markets. http://www.csrwire.com/press_releases/27515-IBM-Expands-Corporate-Service-Corps-in-Emerging-Markets. Accessed 10 May 2013.

CSRWire. (2013). The civic 50: Why IBM’s integrated commitments make it America’s most community-minded company. http://www.csrwire.com/blog/posts/716-the-civic-50-why-ibm-s-integrated-commitments-makes-it-americas-most-community-minded-company. Accessed 10 May 2013.

Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(1), 1–13.

Dawkins, J. (2004). Corporate responsibility: The communication challenge. Journal of Communication Challenge, 9(2), 108–119.

Dobers, P., & Halme, M. (2009). Corporate social responsibility and developing countries. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16(5), 237–249.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2007). Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 24(3), 224–241.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2010). Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. International Journal of Management Review, 12(1), 8–19.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and competitive advantage: Overcoming the trust barrier. Management Science, 57, 1528–1545.

Du, S., Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2008). Exploring the social and business returns of a corporate oral health initiative aimed at disadvantaged hispanic families. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 483–494.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2), 239–263.

Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., & Wicks, A. C. (2007). Managing for stakeholders: Business in the 21st century. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Godfrey, P. C., Merrill, C. B., & Hansen, J. M. (2009). The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal, 30, 425–445.

Greening, D. W., & Turban, D. B. (2000). Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Business and Society, 39(3), 254–280.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Herrbach, O., & Mignonac, K. (2004). How organizational image affects employee attitudes. Human Resource Management Journal, 14(4), 76–88.

Janssen, O., & Van Yperen, N. W. (2004). Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of leader-member exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 368–384.

Kanter, R. M. (2009). SuperCorp: How vanguard companies create innovation, profits, growth, and social good. New York: Crown Publishing Group.

Ketchen, J. D. J., & Shook, C. L. (1996). The application of cluster analysis in strategic management research: An analysis and critique. Strategic Management Journal, 17(6), 441–458.

Kim, H.-R., Lee, M., Lee, H.-T., & Kim, N.-M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility and employee-company identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(4), 557–569.

Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2005). Corporate social responsibility: Doing the most good for your company and your cause. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Lindgreen, A., Cordoba, J. R., Maon, F., & Mendoza, J. M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility in colombia: Making sense of social strategies. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(2), 229–242.

Litz, R. A. (1996). A resource-based-view of the socially responsible firm: Stakeholder interdependence, ethical awareness, and issue responsiveness as strategic assets. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(12), 1355–1363.

Mair, J., Battilana, J., & Cardenas, J. (2012). Organizing for society: A typology of social entrepreneuring models. Journal of Business Ethics, 111, 353–373.

Maurer, T. J., Pierce, H. R., & Shore, L. M. (2002). Perceived beneficiary of employee development activity: A three dimensional social exchange model. Academy of Management Review, 27(3), 432–444.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2000). ‘Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlations or misspecification? Strategic Management Journal, 21, 603–609.

Mirvis, P. (2012). Employee engagement and CSR: Transactional, relational, and developmental approaches. California Management Review, 54(4), 93–117.

Mueller, K., Hattrup, K., Spiess, S., & Lin-Hi, N. (2012). The effects of corporate social responsibility on employees’ affective commitment: A cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(6), 1186–1200.

Peterson, D. K. (2004). The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Business and Society, 43(3), 296–319.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12, 531–544.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89, 62–77.

Preacher, K. I., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavioral Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Punj, G., & Stewart, D. W. (1983). Cluster analysis in marketing research: Review and suggestions for application. Journal of Marketing Research, 20, 134–148.

Raja, U., Johns, G., & Ntalianis, F. (2004). The impact of personality on psychological contracts. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 350–367.

Ramamoorthy, N., & Flood, P. C. (2004). Gender and employee attitudes: The role of organizational justice perceptions. British Journal of Management, 15(3), 247–258.

Robinson, S. L., Kraatz, M. S., & Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Changing obligations and the psychological contract: A longitudinal study. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 137–152.

Robinson, S. L., & Morrison, E. W. (2000). The development of psychological contract breach and violation: A longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 525–546.

Rodrigo, P., & Arenas, D. (2008). ‘Do employees care about CSR programs? A typology of employees according to their attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 265–283.

Rousseau, D. M., & McLean Parks, J. (1993). The contracts of individuals and organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 15, 1–47.

Rupp, D. E., Ganapathi, J., Aguilera, R. V., & Williams, C. A. (2006). Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(4), 537–543.

Schuler, D. A., & Cording, M. (2006). A corporate social performance-corporate financial performance behavioral model for consumer. Academy of Management Review, 31(3), 540–558.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). New York: Academic Press.

Schwartz, M. S., & Carroll, A. B. (2003). Corporate social responsibility: A three-domain approach. Business Ethics Quarterly, 13(4), 503–530.

Schwartz, S. H., & Rubel, T. (2005). Sex differences in value priorities: Cross-cultural and multimethod studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 1010–1028.

Scott, W. R. (1987). The adolescence of institutional theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32(December), 493–511.

Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38, 225–243.

Sen, S., Du, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2009). Building Relationships through Corporate Social Responsibility. In D. J. MacInnis, C. W. Park, & J. R. Priester (Eds.), Handbook of brand relationships (pp. 195–211). Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Surroca, J., Tribo, J. A., & Waddock, S. (2010). Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strategic Management Journal, 31(5), 463–490.

Sweeney, P. D., & McFarlin, D. B. (1997). Process and outcome: Gender differences in the assessment of justice. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18(1), 83–98.

Thompson, J. A., & Bunderson, J. S. (2003). Violations of principle: Ideological currency in the psychological contract. Academy of Management Journal, 28(4), 571–586.

Valentine, S., & Fleischman, G. (2008). Ethics programs, perceived corporate social responsibility and job satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 77, 159–172.

Vasconcelos, A. F. (2008). Broadening even more the internal marketing concept. European Journal of Marketing, 42(11/12), 1246–1264.

Wrzesniewski, A., McCauley, C., Rozin, P., & Schwartz, B. (1997). Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. Journal of Research in Personality, 31, 21–33.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G, Jr, & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Measures for Key Variables

Appendix: Measures for Key Variables

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C.B. & Sen, S. Corporate Social Responsibility, Multi-faceted Job-Products, and Employee Outcomes. J Bus Ethics 131, 319–335 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2286-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2286-5