Abstract

This study examined the relationship between person–organization (PO) fit on prosocial identity (prosocial PO fit) and various employee outcomes. The results of polynomial regression analysis based on a sample of 589 hospital employees, which included medical doctors, nurses, and staff, indicate joint effects of personal and organizational prosocial identity on the development of a sense of organizational identification and on the engagement in prosocial behaviors toward colleagues, organizations, and patients. Specifically, prosocial PO fit had a curvilinear relationship with organizational identification, such that organizational identification increased as organizational prosocial characteristics increased toward personal prosocial identity and then decreased when the organizational prosocial characteristics exceeded the personal prosocial identity. In addition, organizational identification and prosocial behaviors increased as both personal and organizational prosocial identity increased from low to high.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The responsive behavior of people to the prosocial images and characteristics of companies has recently become evident. For example, the public outrage with the slogan “occupy Wall Street” has spread worldwide and challenged the lack of prosocial behavior among companies (New York Times 2011). Stock markets immediately punished the lack of integrity of Goldman Sachs toward clients on the day of disclosures by Greg Smith, former executive director at Goldman Sachs, about the company’s unsavory organizational culture (i.e., the stock price dropped 3.4 %, resulting in a more than $2 billion loss, Bloomberg 2012). Conversely, consumers and employees exhibit great commitment to the organizations with prosocial images and characteristics (Grant et al. 2008; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001).

The cases above are well represented by the emerging concept of prosocial identity, which, at varying levels, can be defined as self-conceptualization that involves helping, benefiting, and empathizing with others (Grant et al. 2009). Recently, Grant et al. have conducted several investigations on the development of personal and organizational prosocial identities (Grant et al. 2008) and their effects on employees’ attitudinal (Grant et al. 2008) and emotional outcomes (Grant et al. 2009). However, despite its potential implications, prosocial identity has received minimal attention. Current research on prosocial identity has focused primarily on examining how organizational prosocial characteristics affect employee outcomes. Identity researchers (e.g., Grant et al. 2008; Tajfel and Turner 1986), however, suggest that individuals can hold a personal prosocial identity. Personal and organizational prosocial identity, instead of being isolated, can be engaged in interactive dynamics to affect employee outcomes (Brewer and Roccas 2001).

Our study examines how personal and organizational prosocial identity jointly affects employee attitudinal (i.e., organizational identification) and behavioral outcomes (i.e., prosocial behaviors). One of the most promising approaches for capturing an interactive relationship between personal and organizational prosocial identity is the person–organization fit (PO fit) framework. The PO fit framework suggests that employees do not react to organizational prosocial image or identity in a monotonically positive manner; instead, the reactive repertories of employees are more complicated and depend on the level of congruence (or incongruence) between personal and organizational prosocial identity (Foreman and Whetten 2002). To capture this intricacy, we employ the polynomial regression analysis and response surface methodology (Edwards 1996). These approaches are more sophisticated, and can capture the potential complexity of the joint effects of personal and organizational prosocial identity on employee outcomes (cf. Edwards and Parry 1993). Specifically, these approaches allow us to test whether organizational identification and prosocial behaviors increase, decrease, or remain constant as organizational prosocial identity fall short or exceed personal prosocial identity as well as both personal and organizational prosocial identity increase from low to high.

Our study also contributes to the literature by examining the effects of prosocial identity on employee outcomes in a unique context. We tested our propositions using Korean hospital employees (medical doctors, nurses, and administrative staff) for several reasons. First, prosocial identities are critical for the success of a hospital because medical professionals with a prosocial identity could be expected to help, benefit, and empathize with others, and helping and caring are directly related to the quality of service in the healthcare sector (Bolon 1997). Second, the relationships between prosocial identities and employee outcomes have been rarely examined in non-Western organizations. To extend the global relevance of management theories in managing nationally diverse workforces, it is important to understand how personal and organizational prosocial identity affects employee outcomes outside the United States such as South Korean culture. For instance, considerable evidence suggests that East Asian cultures are more collective, rather than individual oriented (Schwartz and Bardi 2001). Accordingly, in East Asia, personal and organizational prosocial identity may independently or interactively influence employee outcomes.

Theory and Research Background

Prosocial Identity: A Bipartite Model

Identity is a general self-concept that captures people’s response to the question who am I? (Stryker and Burke 2000). However, social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner 1986) suggests that people hold multiple identities in terms of different abstractions, such as religiosity, gender, or morality. Social identity theory further suggests that self-identity comprises “multi-layered” self-representations rather than a single one, including personal-level identity that reflects an individual’s idiosyncratic characteristics, as well as collective-level identity that reflects salient group classifications (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Tajfel and Turner 1986). For example, intelligence can be a source of personal identity (e.g., I am smart), but self-categorization through membership in intelligent groups (e.g., my group is smart) can be a source of group identity.

In terms of prosocial identity, individuals can develop a sense of personal identity in terms of prosocial attributes, which involve helping, benefiting, and empathizing with others (Grant et al. 2009). These attitudes enable people to see themselves as a prosocial being when they care and help others (Grant 2007; Kaiser and Byrka 2011). On the other hand, people can also see their organizations as a prosocial being when such organizations genuinely care about employees and others in the society and have a strong orientation toward social betterment. For example, Grant et al. (2008) found that people tend to develop both personal and organizational prosocial identities with distinct forms when they engage in organization-sponsored prosocial activities. Specifically, at a personal level, when employees participate in corporate giving programs, they engage in prosocial sense-making about the self through the process of interpreting their actions as caring. Employees then generalize this interpretation to their self-concepts, thus reinforcing their personal-level identity as prosocial. At an organizational level, when employees participate in corporate giving programs, they also engage in prosocial sense-making about the organization through the process of assessing the organization’s contributions as caring. Employees then generalize this interpretation to their views of the organization, thus reinforcing the organization-level identity as prosocial. Thus, evidence suggests that people may hold personal and organizational prosocial identities simultaneously, yet construe such identities as distinct qualities. Next, we discuss how these prosocial identities regulate employee outcomes.

Organizational Prosocial Identity and Employee Reactions

A group of researchers have investigated how employees react to organizational prosocial characteristics. The underlying assumption is that when an organization is perceived to be socially respectful and desirable, organizational members may experience an external prestige and pride of membership, thus satisfying their need for self-esteem or self-enhancement (Bhattacharya et al. 1995; Mael and Ashforth 1992). The enhanced self-esteem, in turn, motivates employees to show greater positive attitudes toward the organization and subsequently produce better work outcomes. This observation was supported by the findings of Maignan and Ferrell (2001), who found that employees tend to show greater levels of organizational commitment when they observe high levels of social participation in their organizations. Similarly, when employees view their organizations as prosocial, they develop positive attitudes and, in turn, perform their in-role jobs better (Carmeli et al. 2007). Employees may also develop extra-role activities for the organization (Lin et al. 2010). Notably, Grant et al. (2008) used the explicit concept of “prosocial identity” and found that employees’ participation in corporate volunteering programs promotes organizational commitment via a prosocial sense-making process in which employees interpret personal and organizational identities as prosocial. Thus, employees tend to exhibit positive reactions to the organization when the organization is considered prosocial.

Although most of the empirical research on organizational prosocial characteristics has been conducted in the United States (Grant et al. 2008), the logic behind the prediction about the relations between prosocial identity and individual behavior and organizational outcomes may not be culture bound and should be investigated in non-US contexts, such as Asian countries. This claim is reasonable because the underlying rationale (i.e., theories of self-enhancement and need for belongingness) has been proven to be a trans-cultural human tendency (see a review of Ellemers et al. 2002). In effect, several non-US studies have shown a similar pattern of findings. For example, Kim et al. (2010) found that Korean employees who perceive the prosocial character of a company are likely to experience a sense of external prestige of the company and, in turn, identify themselves with and show their commitment to this company. Similarly, Lin (2010) used Taiwan employees as a sample and reported that perceived organizational prosocial characteristics (i.e., corporate citizenship) are positively associated with positive attitudes of employees, such as organizational trust, as well as with positive workplace behavior. These positive attitudes go beyond the boundary of in-role job description, including work engagement (Lin 2010) and employee citizenship behavior (Lin et al. 2010). Taken together, we expect organizational prosocial identity to have a positive impact on employees’ attitude (i.e., organizational identification) and prosocial behaviors [i.e., organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and patient caring behavior] among Korean hospital employees.

Hypothesis 1

Organizational prosocial identity will positively correlate with Korean hospital employees’ organizational identification, OCB, and caring behavior.

PO Fit on Prosocial Identity

Although current studies have focused on examining how organizational prosocial characteristics affect employee outcomes, as previously discussed, employees can hold a personal prosocial identity. These two different levels of prosocial identities can also jointly affect the employees’ work attitudes and behavior. However, the vast majority of existing works have postulated that an employee is a passive audience who reacts monotonically and positively to organizational prosocial characteristics (e.g., Maignan and Ferrell 2001). That is, the contribution of individual differences to employees’ reaction to organizational prosocial characteristics has yet to be elucidated. Peterson (2004) noted that employees may react differentially to an organization with a prosocial image, depending upon their attitudes (e.g., attentive or indifferent) toward the prosocialness of the organization. Similarly, Turker (2009) argued that employees exhibit a more positive attitude toward an organization with a prosocial image when they consider the prosocialness of the organization to be important. Thus, it is important to examine how organizational and personal prosocial identity interactively affect employee outcomes.

The PO fit framework is used in this study to capture such interactive dynamics. PO fit theory has been pervasively applied in the field of organizational psychology, organizational behavior, and human resource (HR) management, and higher education (Chatman 1989; Gilbreath et al. 2011; Kristof 1996; Kristof-Brown et al. 2005). PO fit is defined as “the compatibility between people and organization that occurs when at least one entity provides what the other needs, or both share similar fundamental characteristics” (Kristof 1996, pp. 4–5). The concept of PO fit is important to organizations because people who fit well with an organization are likely to exhibit more positive attitudes and behavior (Suar and Khuntia 2010; Verquer et al. 2003). Previous literature has shown that PO fit is positively associated with job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, organizational identification, and citizenship behavior (Chatman 1989; Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Tidwell 2005).

PO fit theory makes use of a variety of predictors and dimensions including personality, skills, needs, and values (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005). In this study, we focus on prosocial identity. PO fit on prosocial identity (thereafter prosocial PO fit) can be defined as the congruence between an individual’s personal and organizational prosocial identities. Based on existing studies on organizational prosocial characteristics, we can expect that employees are likely to show positive work attitudes and behavior when their personal prosocial identity is congruent to their organizational prosocial identity. However, the reaction of employees in the case of mismatch in personal and organizational prosocial identities and the similarity of employee outcomes when personal and organizational prosocial identities are both high versus both low have not yet been fully elucidated. To address these issues, we employed the polynomial regression analysis and response surface methodology, which can capture the potential complexity of the joint effects of personal and organizational prosocial identities on employee outcomes (cf. Edwards and Parry 1993). We therefore turn our attention to the development of specific hypotheses.

Prosocial PO Fit and Organizational Identification

Organizational identification is the “psychological attachment that occurs when members adopt the defining characteristics of the organization as defining characteristics of themselves” (Dutton et al. 1994, p. 242). According to social identity theory, individuals make an effort to develop and maintain a positive self-image, and employees’ identity is interwoven with organizational membership (Tajfel and Turner 1986). When employees’ self-concept is similar to the characteristics of their organization, employees can achieve a feeling of oneness with their organization (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Dutton et al. 1994). It implies that a match between personal and organizational prosocial identities will result in higher employee organizational identification irrespective of the levels of the match.

On the other hand, several researchers (e.g., Grant et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2010) suggest that each personal and organizational prosocial identity is likely to have a main-effect relationship with organizational identification. Specifically, Kim et al. (2010) showed that organizational identification is significantly influenced not only by organizational prosocial activities, but also by their own agency being related to participation in prosocial activities. Similarly, Grant et al. (2008) argued that when an organization aims to do good, both personal and organizational prosocial identities result in increasing a proud sense of being a member of the organization. Extrapolating from this argument, each personal and organizational prosocial identity may have a positive effect on employee outcomes, such that organizational identification would increase as both personal and organizational prosocial identities increase from low to high. This argument is aligned with the existing PO fit studies suggesting that a fit of both person and organization is generally associated with more positive employee outcomes at higher levels than at lower levels (e.g., Cha et al. 2009; Jansen and Kristof-Brown 2005; Livingstone et al. 1997). Taken together, we hypothesize as follows.

Hypothesis 2a

Organizational identification will increase as personal prosocial identity increases toward organizational prosocial identity and will decrease as personal prosocial identity exceeds organizational prosocial identity.

Hypothesis 2b

Organizational identification will be higher when personal and organizational prosocial identities are both high than when both are low.

Prosocial PO Fit and Prosocial Behaviors

Prosocial PO fit can be also related to prosocial behavior such OCB and caring behavior. OCB is defined as an employee’s voluntary activities that may or may not be rewarded but that contribute to the organization by improving the overall function or quality of setting in which work takes place (Organ 1988). Although the dimensionality of OCB can be studied based on different views, such behavior can primarily be categorized into two: behavior directed toward individuals such as helping, courtesy, sportsmanship, and behavior directed toward the organization such as voice, civic virtue, and boosterism (Lee and Allen 2002).

Caring behavior by medical doctors or nurses is defined as acts, conduct, and gestures enacted that convey concern, safety, and attention to the patient (Greenhalgh et al. 1998). Caring behavior has been recognized as an important concept in the healthcare sector because of its critical role in developing positive relationships with and healing patients (Cossette et al. 2007; Graber 2009).

The fit between person and organization is generally believed to result in positive outcomes, whereas a misfit results in negative outcomes (Cable and DeRue 2002; Kristof 1996), which is similar to the effects of prosocial PO fit on organizational identification, as discussed previously. However, the “misfit” can maintain or increase desirable outcomes depending on the types of dimensions of fit or fit outcomes (e.g., Edwards 1996; Edwards and Parry 1993; Jansen and Kristof-Brown 2005). For example, based on the notion of carryover condition, where excess supplies on one dimension can be used to fulfill the demand of other dimensions (Edwards 1996), Jansen and Kristof-Brown (2005) argued that when individuals exceed the pace of the work group, they are more likely to feel greater mastery and control and/or have more opportunities to find satisfying substitutes. They also found that the misfit between individual and work group hurriedness (or pace) had a positive impact on satisfaction and helping behavior.

We propose that the “misfit” between personal and organizational prosocial identity can result in more prosocial behavior than the fit on average. In other words, individuals with either high personal or organizational prosocial identity are more likely to engage in prosocial behavior than those with medium levels of both personal and organizational prosocial identity. Based on the existing arguments on misfit, we focus on two conditions of misfit: (1) when organizational prosocial identity exceeds personal prosocial identity and (2) when personal prosocial identity exceeds organizational prosocial identity. We develop specific hypotheses predicting how these two types of misfit influence prosocial behavior. First, when organizations genuinely care about people in the society and have a strong orientation toward social betterment, although employees do not focus on helping, benefiting, and empathizing with others, employees may expect strong normative incentives for being prosocial and may consequently become motivated to engage in prosocial activities at work (Puffer and Meindl 1992). Second, previous research noted that personal prosocial identity is a strong driver of volunteering activity or helping behavior (Finkelstein et al. 2005). Thus, when employees have high prosocial identity and highly value caring and helping others, they will naturally engage in prosocial behavior to help the community and others, although organizations do not provide prosocial activities nor encourage them to be prosocial. Consistent with this finding, Finkenauer and Meeus (2000) noted that even when a hospital is perceived to be a low prosocial entity, high prosocial medical doctors and nurses would be involved in prosocial actions such as OCB and patient caring because they are highly concerned with helping and empathizing with others.

On the other hand, the variation ranges from low prosocial PO fit (both personal and organizational prosocial identities are low) to high prosocial PO fit (both personal and organizational prosocial identities are high) for fit situations. Theoretically, employees can engage in more prosocial behavior when they and their organization both care about the community and others rather than when both never focus on caring and helping others. Organizations with high prosocial characteristics may offer more and better chances for prosocial employees to fulfill their prosocial values by engaging in OCB and caring behavior. On the contrary, when prosocial PO fit is low, employees may be reluctant to engage in helping or caring behavior because their own prosocial value is feeble, and the organization would less likely appreciate or value such prosocial activities.

In addition, when both personal and organizational prosocial identities are low, employees are not intrinsically motivated nor extrinsically encouraged or socially expected to be prosocial and will thus be less likely to engage in prosocial behavior than when organizational prosocial identity exceeds personal prosocial identity and when personal prosocial identity exceeds organizational prosocial identity. Furthermore, low prosocial PO fit will neutralize the positive effects of high prosocial PO fit on prosocial behavior. As a result, the fit situations, on average, may be less likely to encourage employees to engage in prosocial behavior compared with the two types of misfit. Taken together, we hypothesize the following.

Hypothesis 3a

Organizational citizenship and caring behavior will decrease as personal prosocial identity increases toward organizational prosocial identity and will increase as personal prosocial identity exceeds organizational prosocial identity.

Hypothesis 3b

Organizational citizenship and caring behavior will be higher when personal and organizational prosocial identities are both high than when both are low.

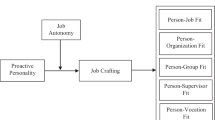

These preceding hypotheses are depicted as three-dimensional surfaces in Fig. 1. Perfect prosocial PO fit is shown by the surface above the diagonal line from the near corner to the far corner of the horizontal plane defined by organization (i.e., organizational prosocial identity) and person (i.e., personal prosocial identity). Figure 1 shows our prediction that when personal and organizational prosocial identities are both high, employees will engage in the highest prosocial behavior, whereas when personal and organizational prosocial identities are both low, employees will engage in the lowest prosocial behavior.

Method

Sample and Procedure

The participants of this study are hospital employees comprising medical doctors, nurses, and administrative staffs. We obtained the list of 307 medium- to large-size hospitals (i.e., an exhaustive set of hospitals with more than 100 beds) from the Korean National Institute of Health. Subsequently, we contacted the HR managers of each hospital. With the assistance of the HR managers, 1805 questionnaires were distributed to 104 hospitals (490 medical doctors, 669 nurses, and 646 staff members). These questionnaires were completed during working hours. Participation was voluntary, and the respondents were assured of the confidentiality of their responses.

Out of returned 589 questionnaires (33 % response rate), 127 were from medical doctors, 231 were from nurses, and 231 were from staff members (response rate: 26 % for medical doctors, 35 % for nurses, and 36 % for staff members). Majority of the medical doctors were males (78 %), whereas most nurses were females (98 %). Most respondents were in their 30–40 s. The average job tenure of all respondents was 9.97 years (SD = 7.81), 6.21 (SD = 5.15) for doctors, 12.67 (SD = 8.69) for nurses, and 9.33 (SD = 7.09) for staff.

Measures

The measures of the variables included in this study are described below. All items were based on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 for strongly disagree to 7 for strongly agree. The survey items were originally in English and translated into Korean following the commonly-used back-translation procedure (Brislin 1986) by English–Korean bilingual professionals who had earned doctoral degrees in the field of management from major public universities in the US. The Korean version was reviewed by HR professionals in hospitals for adjustment in the hospital context and was then piloted to establish the content validity.

Personal and Organizational Prosocial Identities

We adopted Grant et al.’s (2008) scales to assess personal prosocial identity and asked respondents to assess the extent to which they agree with the following two items: “I see myself as caring,” and “I see myself as generous.” To assess the level of organizational prosocial identity, the foregoing items were again used with the exception that the referent in the items referred to “this hospital” instead of “myself.” In Grant et al.’s (2008) original items, one item for personal prosocial identity (i.e., I regularly go out of my way to help others) and one item for organizational prosocial identity (i.e., I see this hospital as being genuinely concerned about its employees) were excluded because both the person and organization should be assessed with the same content dimensions and graded on the same scales for the fit analysis (Edwards 1996).

Organizational Identification

We assessed organizational identification using Kim et al.’s (2010) scale, which reflects the closeness between employees and the hospital. These items are “I feel strong ties with this hospital,” “I experience a strong sense of belongingness to this hospital,” and “I am part of this hospital.”

OCB

OCB was measured by using the 14 items proposed by Lee and Allen (2002). The respondents were asked to determine the degree to which they engage in the given behavior. The exploratory factor analysis clearly determined the two factors that consist of OCB toward individuals (OCBI) and OCB toward organization (OCBO), consistent with Lee and Allen (2002). Sample items of OCBI are: “I willingly give my time to help colleagues who have work-related problems,” “I adjust my work schedule to accommodate other employees’ requests for time off,” and “I show genuine concern and courtesy toward coworkers, even under the most trying business or personal situations.” The examples of OCBO are: “I attend functions that are not required but that help the hospital’s image,” “I defend the hospital when other people criticize it,” and “I express loyalty toward the hospital.”

Caring Behavior

Cossette et al.’s (2007) scale was used to measure caring behavior. Specifically, among the caring nurse–patient interaction scales (Cossette et al. 2007), we used seven items to assess the “Relational Caring Behavior” that focuses on the development of a helping, trusting, and human caring relationship. Sample items include “I help patients to look for a certain equilibrium/balance in their lives,” “I help patients to explore what is important in their lives,” and “I help patients to explore the meaning that they give to their health condition.” This scale involved the participation of nurses and medical doctors, but administrative staff.

Control Variables

To avoid alternative explanations for the employee outcomes, we controlled for the employees’ age, tenure, and educational levels, which have been identified as significant predictors of various employee outcomes (e.g., Hall et al. 1970; Organ and Ryan 1995). We also controlled for employee’s job types (dummy as medical doctor, nurse, and administrative staff) that may affect the participants’ work attitudes and behavior.

Analysis

Polynomial regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between PO fit on prosocial identity and employee outcomes (Edwards and Parry 1993). Polynomial regression analysis tests the complex relationship between personal and organizational prosocial identity as well as the joint effects of such identities on employees’ outcome variable. Polynomial regression analysis has been frequently used in PO fit literature (Edwards and Parry 1993). The general expression for the equation used to test the effects of PO fit on employee outcomes is as follows:

In Eq. 1, P and O represent the personal prosocial and organizational prosocial identity, respectively. The results of Eq. 1 were used to test our hypotheses. The slope of the surface along the O = −P line needs to be examined to test the congruence of P and O. Hypothesis 2a (3a) states that outcomes decrease (increase) on either side of the point of perfect fit (O = P line), implying that this point appears concave (convex) shaped along the O = −P line, with its turning point at O = P. The slope of the surface along the O = −P line can be calculated by setting O equal to −P in Eq. 1:

The quantity (b 3 − b 4 + b 5) is used to analyze the slope of the surface along the O = −P line. If Hypothesis 2a (3a) is supported, b 3 − b 4 + b 5 would be negative (positive) and significant, and the threshold where employee outcomes start to decrease (increase) is above O = P (i.e., non-symmetric relationship). Hypotheses 2b and 3b, which predict that the outcome variable is higher when both personal and organizational prosocial identities are higher than when both are low, can be tested by setting O equal to P in Eq. 1 (Edwards and Parry 1993):

If Hypotheses 2b and 3b are supported, the quantity (b 1 + b 2) would be positive and significant, and b 3 + b 4 + b 5 would not differ from zero.

Results

We conducted confirmatory factor analyses to assess the discriminant validity of the six variables used in this study (i.e., personal and organizational prosocial identities, organizational identification, OCBI, OCBO, and caring behavior). We used three-item parcels for measures with more than three items to reduce the number of indicators (Andre and Werner 2005). We evaluated the model fit using Chi square statistics, Chi square to degrees of freedom ratio, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Researchers suggest that levels of .90 or higher for CFI and TLI and levels of .06 or lower for RMSEA indicate that a model appropriately fits the data (Hu and Bentler 1999). The results show that the six-factor model [χ 2 (589, 89) = 257.12, p < .01; RMSEA = .06; CFI = .98; TLI = .97] fit the data better than the one-factor model [χ 2 (589, 104) = 3366.77, p < .01; RMSEA = .23; CFI = .59; TLI = .46], thus supporting the discriminant validity of the constructs used in this study.

The descriptive statistics, reliability estimates, and correlations for all measures used in this study are reported in Table 1, which shows that all reliability estimates (Cronbach’s alpha) exceeded .87. On average, the employees in our sample assessed that they are more prosocial (M = 5.15) than their organization (M = 4.73). Personal prosocial identity is positively and significantly correlated to organizational prosocial identity, suggesting that both organizations and employees are attractive to those who have similar prosocial characteristics. Personal prosocial identity is more strongly correlated to OCBI and caring behavior than OCBO (r = .58, p < .01; .51, p < .01; .43, p < .01, respectively), whereas organizational prosocial identity is more strongly correlated to OCBO than OCBI and caring behavior (r = .55, p < .01; = .40, p < .01; = .37, p < .01, respectively).

Prosocial PO Fit and Employee Outcomes

Table 2 reveals the results of polynomial regression analyses for the joint effects of personal and organizational prosocial identities on various employee outcomes. Hypothesis 1 stated that organizational prosocial identity would be positively associated with Korean hospital employees’ outcomes. Table 2 shows that the organizational prosocial identity is positively related to organizational identification (b 2 = .35, p < .01), OCB (b 2 = .15, p < .01 for OCBI and b 2 = .36, p < .01 for OCBO), and caring behavior (b 2 = .15, p < .05). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was fully supported.

Hypothesis 2a predicted that organizational identification would increase as personal prosocial identity increases toward organizational prosocial identity and would decrease as personal prosocial identity exceeds organizational prosocial identity. This hypothesis is supported by a negative (i.e., downward) curvature along the P = −O line (i.e., a negative and significant value for b 3 − b 4 + b 5). Table 2 shows that the curvature along the P = −O line for organizational identification is negative and significant (b 3 − b 4 + b 5 = −.20, p < .01). To illustrate the finding, Fig. 2 shows the estimated surfaces for personal and organizational prosocial identities and organizational identification. Along the P = −O line, organizational identification has a curvilinear relationship with personal and organizational prosocial identities (i.e., inversed U-shaped). Specifically, organizational identification increased as the difference between personal prosocial identity and organizational prosocial identity decreases. Specifically, organizational identification increased as organizational prosocial identity increased toward personal prosocial identity (i.e., the negative difference between organizational and personal prosocial identity becomes smaller) and then decreased when organizational prosocial identity exceeded personal prosocial identity. Thus, Hypothesis 2a was supported.

Hypothesis 2b stated that organizational identification would be higher as both personal and organizational prosocial identities increase from low to high. To test this hypothesis, we examined the simple slope along the P = O line at the point P = 0, O = 0 to enable us to observe how organizational identification changes as both personal and organizational prosocial identities increase from low to high. Table 2 shows that the coefficient for b 1 + b 2 is positive and significant (b 1 + b 2 = .59, p < .01). We can also see the upward slope along the P = O line in Fig. 2, which indicates that organizational identification increases as both personal and organizational prosocial identities increase from low to high. Thus, Hypothesis 2b was supported.

Hypothesis 3a predicted that OCB and caring behavior would decrease as personal prosocial identity increases toward organizational prosocial identity and would increase as personal prosocial identity exceeds organizational prosocial identity, which suggests that OCB and caring behavior would increase on either side of the point of perfect fit (O = P line), implying a convex-shaped relationship along the O = –P line with a turning point at O = P. Support for this hypothesis would be evidenced by a positive (i.e., upward) curvature along this line (i.e., a positive and significant value for b 3 − b 4 + b 5). Table 2 shows that the curvature along the P = −O line for OCBI and caring behavior is positive and significant (b 3 − b 4 + b 5 = .16, p < .01; .15, p < .05, respectively). To illustrate the finding, Figs. 3 and 5 show the estimated surfaces for personal and organizational prosocial identities and OCBI and caring behavior. Along the P = −O line, OCBI and caring behavior have a curvilinear relationship with personal and organizational prosocial identities (i.e., U-shaped). Specifically, OCBI and caring behavior decreased as organizational prosocial identity increased toward personal prosocial identity (i.e., the negative difference between organizational and personal prosocial identity becomes smaller) and then increased when organizational prosocial identity exceeded personal prosocial identity. However, the curvature along the P = −O line for OCBO is insignificant (b 3 − b 4 + b 5 = –.05, n.s.). Thus, Hypothesis 3a was supported only for OCBI and caring behavior (Fig. 4).

Hypothesis 3b stated that OCB and caring behavior would increase as both personal and organizational prosocial identities increased from low to high. Table 2 shows that the coefficient for b 1 + b 2 is positive and significant for OCBI, OCBO, and caring behavior (b 1 + b 2 = .45, p < .01; .61, p < .01; .35, p < .01, respectively). The upward slope along the P = O line in Figs. 3, 4, and 5 is also evident. This slope indicates that OCB and caring behavior are higher when both personal and organizational prosocial identities are high instead of low. Thus, Hypothesis 3b was supported.

Discussion

Current research on prosocial activities has enhanced our understanding of the effect of an organization’s prosocial activities on employee outcomes (e.g., Boddy et al. 2010; Carmeli et al. 2007; Turker 2009). However, the dynamic relationship between personal and organizational prosocial characteristics has not yet been established. This study extends the scope of the existing research by considering the joint effect of personal and organizational prosocial identities on employee outcomes by using the PO fit framework.

Theoretical Contributions

Given the scarcity of research on organizational prosocial characteristics and employee outcomes, one important result from this investigation was to enhance the generalization of the linkage between organizational prosocial identity and employee outcomes found in the Western organizational context to cultures outside of the United States. Specifically, our results cross-validate the positive effects of organizational prosocial characteristics on employee work behavior in the Korean hospital context. Thus, our results support and extend Carmeli et al.’s (2007) investigation showing that the effects of organizational prosocal identity on work attitudes and behaviors were similar in the United States and South Korea.

Perhaps the most important implication of our findings is the joint effect of personal and organizational prosocial identities on employee outcomes, which shows that the fit and misfit between organizational and personal prosocial identities significantly affect the employees’ perceived organizational identification as well as their prosocial behaviors. Specifically, we found that as the degree of fit between personal and organizational prosocial identities increased from low to high, organizational identification, OCB, and patient caring behavior increased. These findings suggest that the levels of P and O’s prosocial congruence are important contributors that affect organizational identification and prosocial behavior. These results support and extend the current PO fit research on person–career fit (Cha et al. 2009) and person–job fit (Livingstone et al. 1997) by examining a different fit dimensions (i.e., prosocial identity).

In addition to the fit, the misfit between personal and organizational prosocial identity significantly affects employee outcomes. For example, organizational identification increased as organizational prosocial identity increased toward personal prosocial identity and then decreased when organizational prosocial identity exceeded personal prosocial identity. In addition, employees are likely to engage in more prosocial behavior toward coworkers and patients either when they have high personal prosocial identity or perceive their organization to be highly prosocial than when personal and organizational prosocial identities are both low. These results suggest that employees with low personal prosocial identity working in a highly prosocial organization may be motivated to reciprocate the caring activities of their hospital by taking action that is conducive to other coworkers and patients. On the other hand, employees with high personal prosocial identity working in a low prosocial hospital may consider prosocial behavior towards other coworkers and patients to be a critical part of their job (Coyle-Shapiro et al. 2004), although the activities are not formally required.

However, it is noteworthy that prosocial PO misfit was not found to be significantly related to OCBO. This finding suggests that employees tend to highly engage in OCBO only when both personal and organizational prosocial identities are high. It is plausible that OCBO requires more involvement from both person and environment (i.e., both high personal and organizational prosocial identities), whereas OCBI and caring behavior only need either personal or organizational prosocial identity to be high. Future research needs to confirm these findings and to develop a relevant theory that prescribes a more nuanced relationship between prosocial PO fit and prosocial behavior toward different targets.

Taken together, the findings of this study help to redirect the role of employees from a passive audience to an active agency in terms of organizational prosocial activities. The existing literature generally views that employees react to organizational prosocial activities or characteristics in a monotonically positive way (e.g., Maignan and Ferrell 2001). However, this study challenges this assumption and alternatively suggests that organizations do not entirely control the effects of their prosocial activities on employee outcomes. Rather, employees’ prosocial identity also plays an important role. Thus, our study advances the existing knowledge of an employee’s reaction to organizational prosocial characteristics and activities.

Practical Implications

The results of this study offer several practical implications for HR management and corporate prosocial activities. Given the complex patterns of employee reaction to organizational prosocial characteristics, organizational managers should not quickly conclude that the more effort exerted by the organization as a prosocial entity would more likely result in the development of employees’ positive attitudes toward their organization. Rather, what matters the most is the feature of fit (or alignment) between employees’ personal prosocial identity and organizational prosocial identity. Thus, managers should be aware of individual differences in terms of reacting to organizational prosocial characteristics.

In addition, our findings suggest that organizations need to be “strategic” in seeking to translate organizational prosocial activities into positive employee attitudes and behavior. We found that personal and organization prosocial identities are “substitutive” as well as complementary in promoting positive employee outcomes. These findings suggest that organizational managers need to be selective in involving employees in organizational prosocial activities to foster employees’ prosocial behavior. Also, when their organizational prosocial identity is not as high as it should or could be, managers may focus more on selection, training, and retention to enhance prosocial human capital (i.e., employees with high personal prosocial identity) because building up a prosocial organizational image and characteristics isn’t likely to be easy. For example, in organizations where prosociality is an important part of the organizational culture, potential employees should be screened for their prosocial orientation during the selection process.

Limitations and Future Research

Despite its contribution and useful implications, this study has several limitations. For example, all data were self-reported and collected at a single point in time, raising questions about inflated inter-item correlations because of the common method variance, in which variance is attributable to the measurement source rather than to the constructs that the measures represent (Podsakoff et al. 2003). To examine this problem, we conducted Harman’s one-factor analysis (see Podsakoff and Organ 1986) in which a general factor is found if most variables are related. The result shows that variables differ from one another, which indicates that common method bias is not serious. In addition, common method variance is less likely to have an impact on nonlinear relationships (Crampton and Wagner 1994). Common method variance is unlikely to have influenced the results because most hypotheses in this study are based on curvilinear effects. However, future research needs to corroborate the findings of this study by measuring variables from different sources (e.g., measuring prosocial behavior from supervisors or colleagues) would be useful.

Second, the generalizablity of our findings is limited. The healthcare sector is a non-for-profit organization. The literature also indicates that Korean workers tend to show a strong collective and relational oriented-behavior (Cha 1994). To enhance the generalizability of the current results, future research should aim to examine in the context of profit-oriented organizations and other regions aside from Korean culture.

In conclusion, this study provides interesting implications for prosocial behavior research as well as corporate social responsibility research. The importance study of fit between personal and organizational prosocial identity in examining the reaction of people to organizational prosocial activities is suggested. Organizational scholars have begun to conduct a new wave of research on positive organizational scholarship (POS; Dutton et al. 2006). POS emphasizes positive processes and values and extends the range of what constitutes a positive organizational outcome. In the field of behavioral ethics, POS has encouraged theorists and practitioners to broaden their interests from bad apples and a bad barrel to good apples and a good barrel. This study addresses the positive side of individual and organizational characteristics and should be a stepping stone in embracing the “positive” traditions of POS in the field of prosocial behavior research.

References

Andre, B., & Werner, W. W. (2005). Simulation study on fit indexes in CFA based on data with slightly distorted simple structure. Structural Equation Modeling, 12, 41–75.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14, 20–39.

Bhattacharya, C. B., Rao, H., & Glynn, M. A. (1995). Understanding the bond of identification: An investigation of its correlates among art museum members. Journal of Marketing, 59, 46–57.

Bloomberg. (2012, Mar, 15). Goldman Roiled by Op-Ed Loses $2.2 Billion.

Boddy, C. R., Ladyshewsky, R. K., & Galvin, P. (2010). The influence of corporate psychopaths on corporate social responsibility and organizational commitment to employees. Journal of Business Ethics, 97, 1–19.

Bolon, D. S. (1997). Organizational citizenship behavior among hospital employees: A multidimensional analysis involving job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Hospital and Health Services Administrative, 42, 221–241.

Brewer, M. B., & Roccas, S. (2001). Individual values, social identity, and optimal distinctiveness. In C. Sedikides & M. B. Brewer (Eds.), Individual self, relational self, collective self (pp. 219–237). Ann Arbor, MI: Sheridan Books-Braum Brumfield.

Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. J. Lonner & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research (pp. 137–164). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Cable, D. M., & DeRue, D. S. (2002). The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 875–884.

Carmeli, A., Gillat, G., & Waldman, D. A. (2007). The role of perceived organizational performance in organizational identification, adjustment and job performance. Journal of Management Studies, 44, 972–992.

Cha, J. (1994). Aspects of individualism and collectivism in Korea. In U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, K. S. Choi, & G. Yoon (Eds.), Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method, and applications (pp. 157–174). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cha, J., Kim, Y., & Kim, T. (2009). Person–career fit and employee outcomes among research and development professionals. Human Relations, 62, 1857–1886.

Chatman, J. A. (1989). Improving international organizational research: A model of person–organization fit. Academy of Management Review, 14, 333–349.

Cossette, S., Pepin, J., Cote, J. K., & de Courval, F. P. (2007). The multidimensionality of caring: A confirmatory factor analysis of the caring nurse–patient interaction short scale. JAN: Research Methodology, 23, 699–710.

Crampton, S. M., & Wagner, J. A. (1994). Percept–percept inflation in microorganizational research: An investigation of prevalence and effect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 67–76.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 239–263.

Dutton, J. E., Glynn, M. A., & Spreitzer, G. (2006). Positive organizational scholarship. In J. Greenhaus & G. Callahan (Eds.), Encyclopedia of career development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Edwards, J. R. (1996). An examination of competing versions of the person–environment fit approach to stress. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 292–339.

Edwards, J. R., & Parry, M. E. (1993). On the use of polynomial regression equations as an alternative to difference scores in organizational research. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 1577–1613.

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (2002). Self and social identity. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 161–186.

Finkelstein, M. A., Penner, L. A., & Brannick, M. T. (2005). Motive role identity, and prosocial personality as predictors of volunteer activity. Social Behavior and Personality, 33, 403–418.

Finkenauer, C., & Meeus, W. (2000). How(pro-) social is the caring motive? Psychological Inquiry, 11, 100–103.

Foreman, P., & Whetten, D. A. (2002). Members’ identification with multiple-identity organizations. Organizational Science, 13, 618–635.

Gilbreath, B., Kim, T. Y., & Nichols, B. (2011). Person–environment fit and its effects on university students: A response surface methodology study. Research in Higher Education, 52, 47–62.

Graber, D. R. (2009). Organizational and individual perspectives on caring in hospitals. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 31, 517–537.

Grant, A. M. (2007). Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Academy of Management Review, 32, 393–417.

Grant, A. M., Dutton, J. E., & Ross, B. (2008). Giving commitment: Employee support programs and the prosocial sensemaking process. Academy of Management Journal, 51, 898–918.

Grant, A. M., Molinsky, A., Margolis, J., & Kamin, M. (2009). The performer’s reactions to procedural injustice: When prosocial identity reduces prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39, 319–349.

Greenhalgh, J., Vanhanen, L., & Kyngas, H. (1998). Nursing care behaviors. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 27, 927–932.

Hall, D. T., Schneider, B., & Nygren, H. T. (1970). Personal factors in organizational identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 15, 176–190.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Jansen, K. J., & Kristof-Brown, A. L. (2005). Marching to the beat of a different drummer: Examining the impact of pacing congruence. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 93–105.

Kaiser, F. G., & Byrka, K. (2011). Environmentalism as a trait: Gauging people’s prosocial personality in terms of environmental engagement. International Journal of Psychology, 46, 71–79.

Kim, H., Lee, M., Lee, H., & Kim, N. (2010). Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 9, 557–569.

Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person–organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implication. Personnel Psychology, 49, 1–49.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit’. Personnel Psychology, 58, 281–342.

Lee, K., & Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 131–142.

Lin, C. N. (2010). Modeling corporate citizenship, organizational trust, and work engagement based on attachment theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 517–531.

Lin, C., Lyan, N., Tsai, Y., Chen, W., & Chiu, C. (2010). Modeling corporate citizenship and its relationship with organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 357–372.

Livingstone, L. P., Nelson, D. L., & Barr, S. H. (1997). Person–environment fit and creativity: An examination of supply-value and demand-ability versions of fit. Journal of Management, 23, 119–146.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 103–123.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2001). Antecedents and benefits of corporate citizenship: An investigation of French businesses. Journal of Business Research, 51, 37–51.

New York Times. (2011, Oct, 15). Buoyed by Wall St. Protests, Rallies Sweep the Globe. New York Times.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. New York: Lexington Books.

Organ, D. W., & Ryan, K. (1995). A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 48, 775–802.

Peterson, D. (2004). The relationship between perception of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Business and Society, 43, 296–319.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method bias in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: problem and prospects. Journal of Management, 12, 531–544.

Puffer, S. M., & Meindl, A. R. (1992). The congruence of motives and incentives in a voluntary organization. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 425–434.

Schwartz, S. H., & Bardi, A. (2001). Value hierarchies across cultures: Taking a similarities perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 268–290.

Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38, 225–243.

Stryker, S., & Burke, P. J. (2000). The past present, and future of identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63, 284–297.

Suar, D., & Khuntia, R. (2010). Influence of personal values and value congruence on unethical practices and work behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 97, 443–460.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel (Ed.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago, IL: Nelson Hall.

Tidwell, M. V. (2005). A social identity model of prosocial behaviors within nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 15, 449–467.

Turker, D. (2009). How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 89, 189–204.

Verquer, M. L., Beehr, T. A., & Wagner, S. H. (2003). A meta-analysis of relations between person–organization fit and work attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63, 473–489.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from Hansung University. We also thank Seung-Ho, Park for his support on data collection and James B. Gilbreath for his helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cha, J., Chang, Y.K. & Kim, TY. Person–Organization Fit on Prosocial Identity: Implications on Employee Outcomes. J Bus Ethics 123, 57–69 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1799-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1799-7