Abstract

Theoretical arguments suggest that organizational virtuousness makes individuals surpass their exchange concerns sparking their prosocial motives. This paper focuses on the examination of this issue incorporating two field studies. The first field study examines prosocial motives and social exchange as parallel mediators of the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and three employee outcomes (willingness to support the organization, time commitment, work intensity). The second field study examines prosocial motives, personal sacrifice and impression management motives as parallel mediators of the examined relationships. Both field studies (employing 250 and 354 employees, respectively) indicated that only prosocial motives can mediate the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and employee outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the past decade, concepts of Positive Organizational Scholarship, such as organizational virtuousness, began to attract a growing academic interest (Bright et al. 2006, 2011, 2014; Cameron 2003; Cameron et al. 2004; Caza et al. 2004; Gotsis and Grimani 2015; Rego et al. 2010, 2011, 2015; Sison and Ferrero 2015). Organizational virtuousness is related to strength and excellence in organizational settings (Cameron 2003). A core attribute of organizational virtuousness is its intended positive human impact (Cameron 2003; Cameron and Winn 2012). Doing something good in order to gain self-interested benefits, such as profitability, is not indicative of organizational virtuousness (Cameron and Winn 2012). Organizational virtuousness is characterized by social betterment which extends beyond self-interested concerns and expectations of reciprocity and rewards (Cameron 2003). As a consequence, organizational virtuousness is different from mere support and prioritizes positive human impact. Despite its disinterested nature, organizational virtuousness brings benefits to the organizations, sparking better employee reactions and higher organizational performance (Bright et al. 2006; Cameron et al. 2004; Nikandrou and Tsachouridi 2015; Rego et al. 2010, 2011; Tsachouridi and Nikandrou 2016).

Theoretical arguments have suggested that individuals who perceive virtuousness transcend their exchange and self-interested considerations and develop a prosocial motivation toward the virtuous actor (Cameron 2003). This means that individuals with high perceptions of virtuousness are expected to develop prosocial motives and intrinsically desire to behave positively without entering a pros and cons calculation. Some first empirical findings have supported these theoretical arguments by indicating that employees’ prosocial motives are a response to organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and contribute to the explanation of their subsequent reactions (Tsachouridi and Nikandrou 2018). Nevertheless, we do not know whether social exchange processes play a role in explaining employee reactions to organizational virtuousness’ perceptions. Empirically examining this issue is important, given that the legitimacy of organizational virtuousness is dependent on the material and financial benefits that it can bring to organizations (Cameron 2003; Cameron and Winn 2012). These benefits will be guaranteed if employees really care about their organization and are not motivated by self-interested considerations.

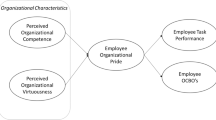

In this study, we aim to contribute to the investigation of this issue. As such, we include prosocial motives and social exchange considerations as parallel mediators of the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and three employee outcomes, namely willingness to support the organization, time commitment and work intensity. The paper includes two field studies. The first study examines the mediating role of prosocial motives and social exchange in the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and employee outcomes (Fig. 1). The second field study aspires to constructively replicate the results of the first field study including the concepts of prosocial motives, personal sacrifice and impression management motives as parallel mediators of the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and employee outcomes (Fig. 2). Personal sacrifice captures employees’ perceived costs of leaving the organization (Dawley et al. 2010; Mitchell et al. 2001). Personal sacrifice is a social exchange concept, as it captures employees’ calculative commitment and their intent to stay and support the organization motivated by the desire to minimize the personal costs in their work life. Impression management motives refer to employees’ desire to influence the perceptions that others have of them in order to gain personal benefits (Bolino et al. 2006, 2008; Rioux and Penner 2001). Similarly to personal sacrifice, impression management motives is a concept of social exchange capturing employees’ desire to create a positive image in order to maximize their benefits within the organization. As such, both personal sacrifice and impression management motives capture employees’ self-interested concerns, thus enabling us to triangulate and further extend the results of Study 1.

Our study makes three important contributions to the existing literature. First of all, it replicates and further extends prior research examining the positive effects of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions on employee outcomes. Previous research has brought to light the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and employee outcomes, such as job satisfaction, affective commitment, intent to quit, willingness to support the organization and organizational citizenship behavior (Nikandrou and Tsachouridi 2015; Rego et al. 2010, 2011; Tsachouridi and Nikandrou 2016). In this study, we aspire to further extend the above stream of research by examining the effects of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions on employees’ willingness to support the organization, time commitment and work intensity. Time commitment and work intensity are dimensions of effort (Brown and Leigh 1996). Until now effort has received limited academic attention, despite its importance for employees’ task and citizenship performance (Brown and Leigh 1996; Piccolo et al. 2010; Pierro et al. 2006).

Second, our study contributes to the study of the mediators of the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and employee outcomes (Rego et al. 2010, 2011; Tsachouridi and Nikandrou 2016, 2018). Including prosocial motives and social exchange considerations as parallel mediators of the examined relationships we shed light on the main reasons driving employee responses to organizational virtuousness.

Third, our study contributes to the literature of social exchange. Social exchange mechanisms have been found to mediate the relationship between various organizational perceptions and subsequent employee outcomes (Agarwal and Bhargava 2014; Allen and Shanock 2013; Byrne et al. 2011; Eisenberger et al. 2001, 2014; Mignonac and Richebé 2013; Muse and Wadsworth 2012; Shore et al. 2006). However, employees are not always motivated by reciprocity and self-interested concerns (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005). Until now scant research has examined prosocial motivation and exchange considerations as parallel mediators of the relationship between employee perceptions and their subsequent reactions (Lemmon and Wayne 2015). Including social exchange considerations and prosocial motives as parallel explanatory mechanisms of employee responses to organizational virtuousness’ perceptions, we extend the above stream of research and we gain insight into the motives hidden behind employees’ positive outcomes. Saying that our aim is to assess the relative power of these two mechanisms and clarify the boundary conditions of the effects of social exchange on employee efforts.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

The Concept of Organizational Virtuousness

Virtuousness could be defined as excellence and the best of human conditions (Aristotle 1985; Cameron 2003). Virtuousness is all about human beings. It denotes the conduct of individuals in organizations toward life-giving behaviors and outcomes and away from that which is life-depleting (Cameron and Caza 2013, p. 683). It is the internal human processes, desires and beliefs that are directed toward having a positive impact on others through human interactions. These internal processes can be self-initiated by the individual or triggered by positive activities of others in organizations.

For individuals to perceive organizational virtuousness in the workplace they need to attribute positive human impact, moral goodness and social betterment in behaviors and processes in organizations. This means that individuals need to perceive actions that go beyond reciprocity and consider them as an end in itself (Bright et al. 2006; Cameron 2003). The amplifying effects of observing and motivating virtuous behaviors create a self-reinforcing upward spiral of helping, thriving, flourishing and so forth for both the individuals and the organization. These nurturing and “life-giving” processes and routines in organizations create what Cameron and Caza (2013) refer to as the “heliotropic effect” and are the result of the eudaemonic tendency of “human beings toward goodness for its intrinsic value” (Cameron and Winn 2012, p. 233). The eudaemonic assumption and the inherent value of organizational virtuousness help us explain how individuals respond when they perceive virtuousness (Meyer, in print). According to Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition people are able to transcend their self-interested concerns and express moral responsibility toward the others, as virtuousness sparks to individuals a quest for the good and renders them to virtuous agents (Arjoon et al. 2018).

Through positive human interactions and a sufficient number of virtuous agents within organizations, enablers are created that promote and extend virtuousness to be embodied in the practices and institutions of the organization (virtuousness through organizations) (Moore et al. 2014). Until now, we have discussed organizational virtuousness at two levels, the individual level and the organizational level. At the individual level, the focus is on the agents and their motivation to perpetuate virtuousness (agent-based approach). At the organizational level, the focus is on organizational practices and outcomes that frame individuals’ prosocial motivation and behavior (action-based approach) (Arjoon et al. 2018).

As such, virtuous agents and virtuous actions are interdependent and enhance each other. According to the literature, there is one more part in the equation which has to do with the existence of a virtuous economy which promotes self-giving instead of subject immersion (Arjoon et al. 2018; Moore and Beadle 2006). Virtuousness can harmonize the needs and goals of all three parts and as a consequence virtuous agents, virtuous organizations and virtuous environments end up being embedded in each other (MacIntyre 1985; Moore and Beadle 2006). Our paper gives emphasis on virtuousness at the individual level and more specifically at employees’ perceptions, motives and behaviors.

Organizational Virtuousness’ Perceptions and Employee Outcomes

Organizational virtuousness has amplifying effects, thus sparking additional manifestations of virtuousness (Bright et al. 2006; Cameron 2003). Individuals perceiving virtuousness experience positive emotions, build strong interpersonal connections and develop a sense of attachment to the virtuous actor (Cameron 2003). Developing an intrinsic desire to do something good, individuals with high organizational virtuousness’ perceptions express positive and supportive behaviors. Research findings have brought to light the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and positive employee reactions, such as organizational citizenship behaviors and willingness to support the organization (Nikandrou and Tsachouridi 2015; Rego et al. 2010; Tsachouridi and Nikandrou 2016). Thus, we expect that:

Hypothesis 1

Organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to employees’ willingness to support the organization

Similarly to willingness to support the organization, we also expect that organizational virtuousness’ perceptions will be positively related to time commitment and work intensity. Time commitment and work intensity are aspects of effort (Brown and Leigh 1996). Time commitment refers to the devotion of time to the organization, while work intensity refers to the devotion of energy to the organization. “Time commitment and work intensity constitute the essence of hard-working” (Brown and Leigh 1996, p. 361). Employees’ time commitment and work intensity are translated into increased task performance and citizenship behaviors (Brown and Leigh 1996; Piccolo et al. 2010).

As time and energy are under employees’ volitional control, employees’ effort is greatly affected by the psychological climate that they perceive (Brown and Leigh 1996). Perceiving ethical behavior from the part of the leader can make employees more willing to express extra effort for the sake of the organization (Piccolo et al. 2010). Perceiving organizational virtuousness can have a similar effect. Organizational virtuousness is associated with a climate of optimism, trust, compassion, integrity and forgiveness (Cameron et al. 2004). Employees who perceive high levels of organizational virtuousness believe that their organization expresses an honest empathetic concern toward them (Cameron 2003). Within a work environment like the aforementioned employees become intrinsically motivated to devote their time and energy to the organization and exert extra effort. Thus, we expect that:

Hypothesis 2

Organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to (a) time commitment and (b) work intensity

Prosocial Motives as Mediator of the Relationship Between Organizational Virtuousness’ Perceptions and Employee Outcomes

Theoretical arguments have suggested that virtuousness transforms the motivation of those who observe it (Cameron 2003). Perceptions of virtuousness can activate the human predisposition to behave in a prosocial way (Cameron 2003; Cameron and Winn 2012). Virtuousness has a contagion effect making human beings flourish and become more virtuous. Individuals who perceive virtuousness gradually transcend their self-interested concerns and become motivated by prosocial motives (Cameron 2003).

In this study, we suggest that perceiving organizational virtuousness can make employees develop prosocial motives toward their organization. In other words, employees with high organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are expected to develop an intrinsic care and concern toward their organization and an honest desire to benefit it. Previous research supports our argument bringing to light that employees’ perceptions of organizational support and virtuousness increase their altruistic motivation (Lemmon and Wayne 2015; Tsachouridi and Nikandrou 2018). Based on the above, we expect that:

Hypothesis 3

Organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to employees’ prosocial motives

Employees’ prosocial motives can spark increased effort and helping behavior (Grant 2007). Research findings have brought to light that prosocial motivation is positively related to organizational citizenship and supportive behavior (Lemmon and Wayne 2015; Rioux and Penner 2001; Tsachouridi and Nikandrou 2018). Employees with prosocial concern for their organization really care about it and want to benefit it, thus behaving positively. Based on this rationale, we expect that employees with high prosocial motives will express high willingness to support the organization, time commitment and work intensity.

Taking into account (a) the expected positive relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and employees’ prosocial motives, (b) the expected positive relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and employee outcomes and (c) the expected positive relationship between prosocial motives and employee outcomes, we expect that prosocial motives will mediate the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and employee outcomes. Employees who perceive organizational virtuousness develop prosocial motives and honestly desire to benefit their organization. As such, they will be more willing to support their organization and devote to it their time and energy. Thus, we expect that:

Hypothesis 4

Prosocial motives mediate the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and (a) employees’ willingness to support the organization, (b) time commitment, (c) work intensity.

Social Exchange as Mediator of the Relationship Between Organizational Virtuousness’ Perceptions and Employee Outcomes

In this study, we also suggest that organizational virtuousness’ perceptions can increase employees’ perceptions of social exchange. According to theoretical arguments, organizational virtuousness’ perceptions enable people to act regardless of reciprocity and social exchange concerns (Cameron 2003). Nevertheless, employees who perceive high levels of organizational virtuousness are expected to believe that they have built a social exchange relationship with their organization for the following reasons.

In contrast to economic exchanges, social exchanges emphasize the socioemotional aspects of the employee-employer relationship and are characterized by trust and long-term orientation (Shore et al. 2006). Within a working environment characterized by organizational virtuousness, employees receive from their organization not only economic benefits, but also socioemotional benefits and they believe that their organization cares about them and treats them with value and respect. Their relationship with their organization is not short-term and narrowly defined. Far from that, it is an open-ended and long-term relationship through which the organization intends to have a positive impact on the lives of employees. Additionally, employees who perceive organizational virtuousness experience increased levels of trust, as trust is an integral aspect of organizational virtuousness (Cameron et al. 2004). Employees with high organizational virtuousness’ perceptions believe that their organization acts disinterestedly and honestly desires to have positive human impact on their lives. This disinterestedness is valuable for employees and may enhance their belief that they have built a beneficial social exchange relationship with their organization (Mignonac and Richebé 2013).

Based on all the above, we expect that employees who perceive high levels of organizational virtuousness will believe that they have built a social exchange relationship their organization. Thus, we expect that:

Hypothesis 5

Organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to social exchange.

In this study, we also seek to empirically examine the role of social exchange considerations in employee reactions to organizational virtuousness’ perceptions. Perceptions of social exchange can motivate employees to behave positively toward their organization trying to return the favorable treatment and continue the beneficial circle of exchanges that they have built with their organization (Byrne et al. 2011; Shore et al. 2006). According to social exchange theory, the behavior of each actor is contingent on the behavior of the other part of the exchange relationship (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005). From this perspective, employees behave positively when they perceive favorable organizational treatment trying to reciprocate the beneficial treatment that they have previously received (Allen and Shanock 2013; Avanzi et al. 2014; Baran et al. 2012; Byrne et al. 2011; Eisenberger et al. 2001; Mignonac and Richebé 2013; Muse and Wadsworth 2012; Ngo et al. 2013; Riggle et al. 2009; Shen et al. 2014; Sulea et al. 2012; Wayne et al. 1997, 2002).

Organizational virtuousness is indicative of favorable organizational treatment and makes employees believe that they have built a beneficial relationship with their organization. As such, employees are expected to behave positively trying to return the favorable treatment. We seek to understand whether these social exchange considerations mediate the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and employee reactions above and beyond prosocial motives. Theoretical arguments rooted in social exchange theory support our claim that social exchange could contribute to the explanation of the effects of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions on employee reactions. Based on all the above, we expect that:

Hypothesis 6

Social exchange mediates the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and (a) employees’ willingness to support the organization, (b) time commitment and (c) work intensity.

Method (Study 1)

Sample and Procedure

Our sample consisted of 250 employees working in organizations of Greece. Seventy undergraduate students of an introduction to management course at a major business school provided names and contact details of 341 employees to participate in our survey. The network of our students included family and friends and provided us the opportunity to access a heterogeneous sample with employees working both in for-profit and organizations in the public sector, as well as in both large and medium size companies. Of these 341 employees, 256 agreed to participate in our survey and returned the questionnaires (participation rate of about 75%). 250 questionnaires were usable. 104 of our respondents were male (41.6%), and 146 were female (58.4%). Our participants had an average age of 38.66 years (SD = 9.75). Regarding the hierarchical position of our participants, 5 (2%) reported an upper management position, 83 (33.2%) reported a middle management position, 46 (18.4%) reported a lower management position, 111 (44.4%) reported a non-managerial position and 5 (2%) did not report their position. The average total work experience of our participants was 14.51 years (SD = 8.82), and their average organizational tenure was 9.72 (SD = 7.97).

Measures

Organizational Virtuousness’ (OV) Perceptions

To measure organizational virtuousness’ perceptions, we employed the 15-item scale of Cameron et al. (2004), which includes five dimensions (optimism, trust, compassion, integrity and forgiveness) loading on the higher order factor of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions. One sample item is: “This organization is characterized by many acts of concern and caring for other people”. Response options ranged from 1 (never true) to 6 (always true).

Due to the multidimensional nature of this measurement instrument, we conducted a higher order CFA using LISREL and maximum likelihood estimation testing this way its validity. The five-factor model (second order) indicated an acceptable fit to our data [χ2 = 175.80, df = 85, Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 0.98, Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) = 0.98, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.99, Incremental Fit Index (IFI) = 0.99, Root–Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.065, Standardized Root–Mean-Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.039). All items loaded significantly on their respective factor with standardized loadings ranging from 0.64 to 0.94, while also the five factors loaded significantly on the higher order factor of organizational virtuousness (0.82–0.94). Each dimension, as well as the construct of organizational virtuousness as a whole had satisfactory reliability, as Cronbach a surpassed 0.7 (optimism: 0.77, trust: 0.79, compassion: 0.86, integrity: 0.95, forgiveness: 0.89, organizational virtuousness: 0.91).

In the subsequent analyses, we used a composite score of organizational virtuousness. As such, we averaged the items of each of the five dimensions to obtain a composite average for each dimension.

Prosocial Motives

To measure prosocial motives, we developed a 3-item scale for the purposes of this study based on the existing literature (Mignonac and Richebé 2013; Rioux and Penner 2001). The three items used were the following: “It is important for me to help my organization regardless of whether I will have a personal benefit”, “When I support my organization I do it because I really care”, and “It is important for me to help my organization when it needs it”. Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (Cronbach a = 0.91).

Social Exchange

To measure social exchange, we used five items from the scale of Shore et al. (2006). One sample item is: “I don’t mind working hard today- I know I will eventually be rewarded by my organization”. Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach a of this scale was 0.89.

Willingness to Support the Organization

We measured employees’ willingness to support the organization adapting four items from Choi and Mai-Dalton’s scale (1999), which measures employees’ intentions to reciprocate the treatment received by their leader. One sample item is: “If asked to do something to help the company, I would do this even if it might involve extra responsibility”. A 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was used (Cronbach a = 0.83).

Time Commitment

To measure time commitment, we used four items from the scale of Brown and Leigh (1996), Sample item is: “Other people know me by the long hours I keep”. Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (Cronbach a = 0.82).

Work Intensity

We measured work intensity with the 5-item scale of Brown and Leigh (1996). One sample item is: “When I work, I do so with intensity”. A 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was used (Cronbach a = 0.87).

Validation of our Measurement Model

Before testing our hypotheses, we conducted a Confirmatory Factor Analysis using LISREL and Maximum Likelihood Estimation. Doing so, we tested the validity of our overall measurement model (organizational virtuousness’ perceptions, prosocial motives, social exchange, willingness to support the organization, time commitment and work intensity). Fit indices confirmed the acceptable fit of our measurement model [χ2 = 441.60, df = 284, NFI = 0.96, NNFI = 0.98, CFI = 0.98, IFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.047, SRMR = 0.05]. There was convergent and discriminant validity as Average Variance Extracted (AVE) surpassed 0.5 and was greater than the squared correlation between each couple of constructs. Descriptive statistics, reliabilities and correlations among the constructs of our model are presented in Table 1.

As our data were self-reported, we took some measures to reduce common method variance. As such, we guaranteed anonymity and we provided verbal statements for the midpoints of the scales (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Single factor measurement model (Harman’s Single Factor Test) indicated unacceptable fit. This alleviates concerns regarding common method variance (χ2 = 2681.99, df = 299, NFI = 0.81, NNFI = 0.82, CFI = 0.84, IFI = 0.84, RMSEA = 0.18, SRMR = 0.13).

Results (Study 1)

To test our Hypotheses, we employed PROCESS macro for SPSS (model 4) (Hayes 2013). PROCESS macro enabled us to examine multiple mediator models with parallel mediators, as well as to acquire bootstrapped confidence intervals of the effects estimated. In our analyses, organizational virtuousness’ perceptions was the independent variable, prosocial motives and social exchange were the mediators, while willingness to support the organization, time commitment and work intensity were the dependent variables. We averaged the items of each construct to use their composite scores in the analyses. In the case of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions, we averaged the averages of each of the five dimensions in order to obtain a composite score of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions for each employee. We controlled for the effects of gender, age, hierarchical position, years of total work experience and years of organizational tenure.

Organizational Virtuousness’ Perceptions and Willingness to Support the Organization Relationship

The results of the analysis (Table 2) indicate that organizational virtuousness’ perceptions have a statistically significant positive relationship with willingness to support the organization (b = 0.49, t = 9.53, p < 0.001), as well as with both mediators (prosocial motives: b = 0.57, t = 12.37, p < 0.001, social exchange: b = 0.63, t = 14.14, p < 0.001) (Hypothesis 1, Hypothesis 3 and Hypothesis 5 supported). Additionally, prosocial motives (but not social exchange) have a statistically significant positive relationship with willingness to support the organization (see Table 2). After controlling for the effects of mediators on the dependent variable, the effect of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions on the dependent variable decreases in magnitude but remains statistically significant (b = 0.21, t = 3.09, p < 0.01) indicating partial mediation. The examination of the specific indirect effects indicates that only prosocial motives (but not social exchange) mediate (see Table 2) the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable, as the confidence intervals of this indirect effect do not contain zero (Hypothesis 4a supported, Hypothesis 6a failed to receive support).

Organizational Virtuousness’ Perceptions and Time Commitment Relationship

The analysis (Table 2) indicates that organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are not significantly related to time commitment (b= − 0.03, t= − 0.57, p > 0.10) (Hypothesis 2a failed to receive support), while they have a statistically significant relationship with both mediators. As none of the mediators has a statistically significant relationship with time commitment (see Table 2), neither prosocial motives nor social exchange mediate the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and time commitment (Hypothesis 4b and Hypothesis 6b failed to receive support).

Organizational Virtuousness’ Perceptions and Work Intensity Relationship

The results of the analysis (Table 2) indicate that organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to work intensity (b = 0.16, t = 3.46, p < 0.001) (Hypothesis 2b supported), as well as to mediators. Regarding the effects of the mediators on the dependent variables, prosocial motives (but not social exchange) have a statistically significant positive relationship with work intensity (see Table 2). After controlling for mediators, the effect of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions on the dependent variable becomes nonsignificant indicating full mediation (b = 0.05, t = 0.79, p > 0.10). The examination of the specific indirect effects indicates that only prosocial motives (but not social exchange) (Table 2) mediate the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and work intensity (Hypothesis 4c supported, Hypothesis 6c failed to receive support).

Study 2

Study 2 builds on the findings of Study 1 by examining prosocial motives, personal sacrifice and impression management motives as parallel mediators of the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and employee outcomes. Personal sacrifice and impression management motives are rooted in the social exchange rationale and are able to motivate employees to support their organization and exert extra effort at their attempt to gain personal benefits (Dawley et al. 2010; Rioux and Penner 2001).

Employees with high personal sacrifice believe that working in this organization is a significant investment from their part and that leaving the organization would have material and psychological costs (Dawley et al. 2010). As such, they desire to stay and support their organization believing that it is advantageous for them to continue the beneficial exchange that they have built with their organization. Employees perceiving organizational virtuousness believe that their organization has a positive impact on their life and perceive a favorable organizational treatment. As such, they are expected to believe that leaving their organization would have great costs for them. Based on this rationale, we expect that organizational virtuousness’ perceptions increase employees’ perceptions of personal sacrifice, thus making them behave positively within organizational settings. As such, we expect that in addition to prosocial motives, personal sacrifice can also motivate employees to respond positively to organizational virtuousness’ perceptions. Thus:

Hypothesis 7

Organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to personal sacrifice.

Hypothesis 8

Personal sacrifice mediates the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and (a) willingness to support the organization, (b) time commitment and (c) work intensity.

Similarly to personal sacrifice, we also expect that impression management motives may play an important role for explaining employee responses to organizational virtuousness. Employees with high impression management motives desire to build a positive image. As such, they behave positively within organizational settings, because they believe that they will gain personal benefits through benefitting their organization and building a positive image (Rioux and Penner 2001). Theoretical arguments suggest that virtuousness makes individuals surpass their self-interested concerns (Cameron 2003). However, organizational virtuousness making employees believe that their organization recognizes and repays their effort may also spark their desire to maximize their personal benefits. Being confident that their organization provides them with benefits and offers to them what they deserve, employees may develop a desire to improve their image within the organization in order to gain more personal benefits. From this perspective, employees who perceive high levels of organizational virtuousness are expected to express increased impression management motives, because they know that the more they offer the more they gain. Empirical findings indicating that perceptions of support are positively related to employees’ impression management tactics (Shore and Wayne 1993) further support the aforementioned argument. Based on the above, we expect that in addition to prosocial motives and personal sacrifice, impression management motives can contribute to the explanation of the effects of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions on employee outcomes. Thus, we expect that:

Hypothesis 9

Organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to impression management motives.

Hypothesis 10

Impression management motives mediate the relationship between organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and (a) willingness to support the organization, (b) time commitment and (c) work intensity.

Method (Study 2)

Sample and Procedure

Similarly to Study 1, we employed the same methodology to conduct a second field study. 354 employees working in for profit and public organizations, as well as large and medium size companies in Greece took part in this survey. One hundred and seventeen students of an organizational behavior course at a major business school provided names and contact details of 471 employees to participate in our survey. 358 of these employees agreed to participate (participation rate of about 76%) and returned the questionnaires. Of the 358 returned questionnaires, 354 were usable. Our sample consisted of 164 males (46.3%) and 189 females (53.4%) and 1 (0.3%) who did not specify his/her gender. Our participants had an average age of 38.43 years (SD = 10.88). Among our participants, 48 (13.6%) reported an upper management position, 113 (31.9%) reported a middle management position, 46 (13%) reported a lower management position, 144 (40.7%) reported a non-managerial position, and 3 (0.8%) did not report their position. Our participants had an average total work experience of 14.72 years (SD = 9.96) and an average organizational tenure of 8.68 (SD = 7.83).

Measures

Organizational Virtuousness’ Perceptions

We measured Organizational virtuousness’ perceptions with the same 15-item scale of Cameron et al. (2004), as we did in Study 1. The multidimensional scale of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions had acceptable fit (χ2 = 245.74, df = 85, NFI = 0.98, NNFI = 0.98, CFI = 0.98, IFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.073, SRMR = 0.037). All items loaded significantly on their respective factor and their standardized loadings ranged from 0.62 to 0.94. Moreover, the five factors loaded significantly on the higher order factor of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions with standardized loadings ranging from 0.83 to 0.93. Each dimension, as well as the construct of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions as a whole had satisfactory reliability, as Cronbach a surpassed 0.7 (optimism: 0.75, trust: 0.82, compassion: 0.87, integrity: 0.94, forgiveness: 0.90, organizational virtuousness: 0.91).

Prosocial Motives

We measured prosocial motives with a 3-item scale adapted from the scales of Mignonac and Richebé (2013) and Rioux and Penner (2001), as we did in Study 1 (Cronbach a = 0.91).

Personal Sacrifice

We measured personal sacrifice with the 6-item scale developed by Meyer and Allen (1997), as used by Dawley et al. (2010). Sample item is: “For me personally, the costs of leaving this organization would be far greater than the benefits”. Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (Cronbach a = 0.87).

Impression Management Motives

To measure impression management motives, we adapted 4 items from the scale of Rioux and Penner (2001). The items used were the following: “When I help the organization, I often do it because rewards are important to me”, “When I support the organization, I often do it because I want to make a good impression”, “When I support the organization, I often do it in order to gain personal benefits” and “When I help the organization, I often do it because I want to raise”. Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (Cronbach = 0.86).

Willingness to Support the Organization

We measured willingness to support the organization with the same 4-item scale (adapted from Choi and Mai-Dalton 1999) as we did in Study 1 (Cronbach a = 0.85).

Time Commitment

We measured time commitment with the 5-item scale of Brown and Leigh (1996) (Cronbach a = 0.88).

Work Intensity

To measure work intensity, we used the 5-item scale of Brown and Leigh (1996), as we did in Study 1 (Cronbach a = 0.89).

Validation of the Whole Measurement Model

A CFA including all the variables of the measurement model confirmed the acceptable fit of the model (χ2 = 1029.86, df = 443, NFI = 0.94, NNFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.97, IFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.061, SRMR = 0.065). Moreover, there was convergent and discriminant validity for all constructs, as the AVE of each construct surpassed 0.50 and was greater than the squared correlation between each couple of constructs. Descriptive statistics, reliabilities and correlations among the constructs of our model are presented in Table 3.

Single factor measurement model indicated unacceptable fit alleviating concerns regarding common method variance (χ2 = 6569.74, df = 464, NFI = 0.73, NNFI = 0.73, CFI = 0.75, IFI = 0.75, RMSEA = 0.19, SRMR = 0.15).

Results (Study 2)

To test our Hypotheses, we employed again the PROCESS macro for SPSS (model 4) (Hayes 2013). In our analyses, organizational virtuousness’ perceptions was the independent variable, prosocial motives, personal sacrifice and impression management motives were the mediators, while willingness to support the organization, time commitment and work intensity were the dependent variables. Gender, age, hierarchical position, years of total work experience and years of organizational tenure were used as control variables.

Organizational Virtuousness’ Perceptions and Willingness to Support the Organization Relationship

The results of the analysis (Table 4) bring to light that organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to willingness to support the organization (b = 0.50, t = 13.63, p < 0.001) (Hypothesis 1 supported). Moreover, organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to prosocial motives (b = 0.48, t = 13.26, p < 0.001) (Hypothesis 3 supported). Our results also indicate that that organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to personal sacrifice (b = 0.31, t = 8.01, p < 0.001) and negatively related to impression management motives (b = − 0.10, t = − 2.04, p < 0.05) (Hypothesis 7 supported, Hypothesis 9 failed to receive support). Regarding the effects of mediators on the dependent variable, only prosocial motives (but not personal sacrifice and impression management motives) have a positive effect on willingness to support the organization (see Table 4). After controlling for mediators, organizational virtuousness’ perceptions still exert a statistically significant effect on the dependent variable, but this effect is decreased (b = 0.31, t = 7.03, p < 0.001) indicating partial mediation. The examination of the specific indirect effects indicates that only prosocial motives mediate the relationship between the independent and the dependent variable (see Table 4) (Hypothesis 4a supported). Personal sacrifice and impression management motives cannot contribute to the explanation of the examined relationship above and beyond prosocial motives, as the confidence intervals of the indirect effects through personal sacrifice and impression management motives include zero (Hypothesis 8a and Hypothesis 10a failed to receive support).

Organizational Virtuousness’ Perceptions and Time Commitment Relationship

Our results (Table 4) indicate that organizational virtuousness’ perceptions do not have a significant relationship with time commitment (b = 0.07, t = 1.59, p = 0.11) (Hypothesis 2a failed to receive support) (Table 4). As such, Hypothesis 4b, 8b and 10b failed to receive support.

Organizational Virtuousness’ Perceptions and Work Intensity Relationship

Our results indicate that organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to work intensity (b = 0.25, t = 7.32, p < 0.001) (Hypothesis 2b supported). Additionally, organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to prosocial motives and prosocial motives are positively related to work intensity (see Table 4). Similarly, organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are positively related to personal sacrifice, while personal sacrifice is also positively related to work intensity. In contrast, organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are negatively related to impression management motives and impression management motives are not significantly related to work intensity. After controlling for mediators, the effect of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions on work intensity becomes nonsignificant indicating full mediation (b = 0.07, t = 1.69, p > 0.05). The examination of the specific indirect effects indicates that only prosocial motives mediate the positive relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable (Hypothesis 4c supported) (see Table 4). Personal sacrifice and impression management motives fail to mediate such relationship above and beyond prosocial motives (Hypothesis 8c and Hypothesis 10c failed to receive support).

General Discussion

Until now, existing research has supported that organizational virtuousness’ perceptions can have a profound impact on employee cognitions, emotions and behaviors. To the extent that employees perceive virtuous organizational behaviors, they enter an upward spiral and exhibit positive attitudes, such as job satisfaction, affective commitment and work engagement, as well as with employee behaviors and behavioral intentions, such as intent to quit, task crafting, performance, organizational spontaneity and organizational citizenship behavior (Ahmed et al. 2018; Hur et al. 2017; Nikandrou and Tsachouridi 2015; Rego et al. 2010, 2011; Singh et al. 2018; Tsachouridi and Nikandrou 2016). In our study, we examine the impact of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions on three employee outcomes, namely willingness to support the organization, time commitment and work intensity.

According to our findings, employees who perceive high levels of organizational virtuousness are willing to support their organization. Nikandrou and Tsachouridi (2015) argued that organizational virtuousness perceptions affect employees’ willingness to support the organization even in hard times which in turn can enable the organization to bounce back from adversity in the long-run. This study extends the above-mentioned findings by suggesting that employees develop prosocial motives as a response to their organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and support the organization.

Next, we examined the role of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions in employees’ exertion of effort. How hard a person works (work intensity) and how many hours he/she devotes to the job (time commitment) are operationalizations of effort (Brown and Leigh 1996; Piccolo et al. 2010). Based on our findings, time commitment does not seem to be formed by employees’ organizational virtuousness’ perceptions, meaning that employees may already work long hours and are unaffected by the organizational context. On the other hand, employees are motivated to work harder when they observe organizational behaviors and practices that facilitate human flourishing in the workplace. These findings add to the study of effort by bringing to light that time commitment and work intensity may have different antecedents and as such they need separate attention (Brown and Leigh 1996; Piccolo et al. 2010). Moreover, prosocial motives and not social exchange processes are important for employees who observe virtuous organizational behaviors to exhibit hard work.

Previous studies have examined the underlying mechanisms between organizational virtuousness perceptions and employee attitudes and behaviors. The main focus has been on explaining employees’ positive attitudes and behaviors as a result of affective and cognitive attachment to the organization (Ahmed et al. 2018; Hur et al. 2017; Rego et al. 2010, 2011; Tsachouridi and Nikandrou 2016). They have viewed such attachment through a social exchange filter claiming that positive behaviors are elicited in order to reciprocate the perceived virtuous organization. They have based their results on the assumption of reciprocity without actually incorporating social exchange constructs in their models. Moreover, despite the theoretical argument regarding the impact of organizational virtuousness on the development of prosocial motivation of those who observe it, existing literature has given scant empirical attention to the role of prosocial motives in explaining positive employee responses to organizational virtuousness (Tsachouridi and Nikandrou 2018). Our work incorporates prosocial motives and social exchange mechanisms simultaneously as explanatory factors of the effects of organizational virtuousness on three employee outcomes, namely willing to support the organization, work intensity and time commitment.

Our paper contributed to the investigation of this issue by bringing to light that prosocial motives are able to explain the effects of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions above and beyond social exchange considerations. This means that employees who perceive organizational virtuousness desire to behave positively, because they honestly care about their organization and not because they enter a pros and cons calculation and social exchange considerations. The fact that employees view organizational virtuousness as a signal of a high quality social exchange relationship, does not mean that they base their subsequent reactions on social exchange considerations. This is of utmost importance, given that during periods of crisis organizations may be unable to spark beneficial exchanges with their employees. These findings highlight the pragmatic value of organizational virtuousness by indicating its ability to make employees surpass their self-interested concerns and act based on their prosocial motivation toward their organization. These findings provide an alternative view of the employee–employer relationship which until now has been viewed from the perspective of reciprocity and social exchange (Agarwal and Bhargava 2014; Byrne et al. 2011; Mignonac and Richebé 2013; Shore et al. 2006; Sulea et al. 2012).

Following, we conducted a second field study to examine more closely the social exchange mechanisms. This study incorporates two social exchange mechanisms (personal sacrifice and impression management motives) as potential mediators of the effects of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions on employee outcomes. Both personal sacrifice and impression management motives connote exchange and self-interested considerations and have been found to explain subsequent employee reactions (Dawley et al. 2010; Rioux and Penner 2001). Our results supported the findings of Study 1 and indicated that neither personal sacrifice nor impression management motives can contribute to the explanation of the effects of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions on employee reactions above and beyond prosocial motives. Of special importance is also the fact that organizational virtuousness’ perceptions are negatively related to impression management motives. This means that employees who perceive high levels of organizational virtuousness typically do not care as much about creating a positive image and do not enter self-interested concerns. Contrary to perceptions of support (Shore and Wayne 1993), organizational virtuousness impedes employees from entering impression management considerations. These findings open directions for future research and highlight the ability of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions to transform employees’ motivation and subsequent behavior.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Our research has some limitations that provide useful directions for future research. Our paper incorporating two field studies provides us the opportunity to triangulate our results and be more confident in our findings. However, the cross-sectional nature of our findings limits our ability to claim causality. Future longitudinal designs could address this issue.

Moreover, our findings shed light to the mediating mechanisms explaining the effects of organizational virtuousness on employee outcomes. More research is needed in order to understand the mechanisms through which observing individual and organizational virtuous behaviors can spark positive employee reactions. We need to understand how within an organizational virtuousness context human interactions and processes make employees develop prosocial motivation and positive actions. Examining organizational virtuousness at the level of interpersonal relations will enable us to have a better insight into the inherent value of virtuousness and of the phenomenon of “heliotropic effect”.

Additionally, at another level the broader social environment can promote a self-giving or a materialistic culture (Arjoon et al. 2018).This means that different cultural values can affect both organizational conduct and employee behaviors. Future research could include cultural dimensions as a factor influencing how employees respond to organizational virtuousness and whether they develop exchange or prosocial motives. Examining the manifestations and the interplay of prosocial motives and social exchange considerations at the individual, organizational and societal levels can enrich our knowledge on promoting a common good toward the goal of eudaimonia and human flourishing.

Practical Implications and Conclusion

Despite its disinterested nature, organizational virtuousness brings benefits to the organizations, as it makes employees more willing to support the organization and work with intensity motivated by prosocial motives. This paper has several practical implications. Οrganizational virtuousness is associated with organizational practices that support virtuous behaviors. Thus, the human resources department should develop practices aligned with the organizational virtues of integrity, trust, compassion, forgiveness and optimism. This could happen through various ways. Open channels of communication should be part of organizational practices. Through these channels, virtuous actions could be transmitted to all organizational members. Doing so, the prosocial motivation of employees could be activated. Providing employees with a second chance to learn from their mistakes and become better, expressing respect toward their problems and creating a climate of compassion can increase employees’ organizational virtuousness’ perceptions and unlock their prosocial motivation, thus leading to increased effort and willingness to support the organization. Managers as agents of the organization should be selected to fit the organizational ethos and trained based on the principles of organizational virtuousness. This could create virtuous agents who could implement and promote virtuousness in the workplace.

In conclusion, our research highlights the benefits of organizational virtuousness bringing to light its ability to make employees surpass their self-interested considerations and behave positively driven by a prosocial motivation. Organizational agents at all levels should understand that the organization does not merely support them, but cares about them and prioritizes positive human impact.

References

Agarwal, U. A., & Bhargava, S. (2014). The role of social exchange on work outcomes: a study of Indian managers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(10), 1484–1504.

Ahmed, I., Rehman, W., Ali, F., Ali, G., & Anwar, F. (2018). Predicting employee performance through organizational virtuousness: Mediation by affective well-being and work engagement. Journal of Management Development, 37(6), 493–502.

Allen, D. G., & Shanock, L. R. (2013). Perceived organizational support and embeddedness as key mechanisms connecting socialization tactics to commitment and turnover among new employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34, 350–369.

Aristotle. (1985). Nicomachean ethics (T. Irwin, Trans.). Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

Arjoon, S., Turriago-Hoyos, A., & Thoene, U. (2018). Virtuousness and the common good as a conceptual framework for harmonizing the goals of the individual, organizations, and the economy. Journal of Business Ethics, 147(1), 143–163.

Avanzi, L., Fraccaroli, F., Sarchielli, G., Ullrich, J., & van Dick, R. (2014). Staying or leaving: A combined social identity and social exchange approach to predicting employee turnover intentions. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 63(3), 272–289.

Baran, B. E., Shanock, L. R., & Miller, L. R. (2012). Advancing organizational support theory into the twenty-first century world of work. Journal of Business Psychology, 27, 123–147.

Bolino, M. C., Kacmar, K. M., Turnley, W. H., & Gilstrap, J. B. (2008). A multi-level review of impression management motives and behaviors. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1080–1109.

Bolino, M. C., Varela, J. A., Bande, B., & Turnley, W. H. (2006). The impact of impression-management tactics on supervisor ratings of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 281–297.

Bright, D. S., Cameron, K. S., & Caza, A. (2006). The amplifying and buffering effects of virtuousness in downsized organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 64, 249–269.

Bright, D. S., Stansbury, J., Alzola, M., & Stavros, J. M. (2011). Virtue ethics in positive organizational scholarship: An integrative perspective. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 28(3), 231–243.

Bright, D. S., Winn, B. A., & Kanov, J. (2014). Reconsidering virtue: Differences of perspective in virtue ethics and the positive social sciences. Journal of Business Ethics, 119, 445–460.

Brown, S. P., & Leigh, T. W. (1996). A new look at psychological climate and its relationship to job involvement, effort, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 358–368.

Byrne, Z., Pitts, V., Chiaburu, D., & Steiner, Z. (2011). Managerial trustworthiness and social exchange with the organization. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 26(2), 108–122.

Cameron, K. S. (2003). Organizational virtuousness and performance. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 48–65). San Fransisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Cameron, K. S., Bright, D. S., & Caza, A. (2004). Exploring the relationships between organizational virtuousness and performance. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(6), 766–790.

Cameron, K. S., & Caza, A. (2013). Virtuousness as a source of happiness in organizations. In S. A. David, I. Boniwell & A. C. Ayers (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 676–692). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cameron, K. S., & Winn, B. (2012). Virtuosuness in organizations. In K. S. Cameorn & G. M. Spreitzer (Eds.), The oxford handook of positive organizational scholarship (pp. 231–243). New York: Oxford University Press.

Caza, A., Barker, B. A., & Cameron, K. S. (2004). Ethics and ethos: The buffering and amplifying effects of ethical behavior and virtuousness. Journal of Business Ethics, 52, 169–178.

Choi, Y., & Mai-Dalton, R. R. (1999). The model of followers’ responses to self-sacrificial leadership: An empirical test. The Leadership Quarterly, 10, 397–421.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31, 874–900.

Dawley, D., Houghton, J. D., & Bucklew, N. S. (2010). Perceived organizational support and turnover intention: The mediating effects of personal sacrifice and job fit. The Journal of Social Psychology, 150(3), 238–257.

Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P. D., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 42–51.

Eisenberger, R., Shoss, M. K., Karagonlar, G., Gonzalez-Morales, M. G., Wickham, R. E., & Buffardi, L. C. (2014). The supervisor POS–LMX–subordinate POS chain: Moderation by reciprocation wariness and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35, 635–656.

Gotsis, G., & Grimani, K. (2015). Virtue theory and organizational behavior: an integrative framework. Journal of Management Development, 34(10), 1288–1309.

Grant, A. M. (2007). Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 393–417.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Hur, W., Shin, Y., Rhee, S., & Kim, H. (2017). Organizational virtuousness perceptions and task crafting: The mediating roles of organizational identification and work engagement. Career Development International, 22(4), 436–459.

Lemmon, G., & Wayne, S. J. (2015). Underlying motives of organizational citizenship behavior: Comparing egoistic and altruistic motivations. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 22(2), 129–148.

MacIntyre, A. (1985). After virtue (2nd edn.). London: Duckworth.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application. London: Sage.

Meyer, M. (2018, in print). The evolution and challenges of the concept of organizational virtuousness in positive organizational scholarship. Journal of Business Ethics.

Mignonac, K., & Richebé, N. (2013). No strings attached?: How attribution of disinterested support affects employee retention. Human Resource Management Journal, 23(1), 72–90.

Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., & Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1102–1121.

Moore, G., & Beadle, R. (2006). In search of organizational virtue in business: Agents, goods, practices, institutions and environments. Organizational Studies, 33(3), 369–389.

Moore, G., Beadle, R., & Rowlands, A. (2014). Catholic social teaching and the firm. Crowding in virtue: A macintyrean approach to business ethics. American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly, 88(4), 779–805.

Muse, L. A., & Wadsworth, L. L. (2012). An examination of traditional versus non traditional benefits. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(2), 112–131.

Ngo, H., Loi, R., Foley, S., Zheng, X., & Zhang, L. (2013). Perceptions of organizational context and job attitudes: The mediating effect of organizational identification. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 30, 149–168.

Nikandrou, I., & Tsachouridi, I. (2015). Towards a better understanding of the “buffering effects” of organizational virtuousness’ perceptions on employee outcomes. Management Decision, 53(8), 1823–1842.

Piccolo, R. F., Greenbaum, R., Hartog, D. N.D., & Folger, R. (2010). The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31, 259–278.

Pierro, A., Kruglanski, A. W., & Higgins, E. T. (2006). Progress takes work: Effects of the locomotion dimension on job involvement, effort investment, and job performance in organizations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 1723–1743.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Rego, A., Reis Junior, D., & Cunha, M. P. (2015). Authentic leaders promoting store performance: The mediating roles of virtuousness and potency. Journal of Business Ethics, 128, 617–634.

Rego, A., Ribeiro, N., & Cunha, M. P. (2010). Perceptions of organizational virtuousness and happiness as predictors of organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 93, 215–235.

Rego, A., Ribeiro, N., Cunha, M. P., & Jesuino, J. C. (2011). How happiness mediates the organizational virtuousness and affective commitment relationship. Journal of Business Research, 64(5), 524–532.

Riggle, R. J., Edmondson, D. R., & Hansen, J. D. (2009). A meta-analysis of the relationship between perceived organizational support and job outcomes: 20 years of research. Journal of Business Research, 62(10), 1027–1030.

Rioux, S. M., & Penner, L. A. (2001). The causes of organizational citizenship behavior: A motivational analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(6), 1306–1314.

Shen, Y., Jackson, T., Ding, C., Yuan, D., Zhao, L., Dou, Y., & Zhang, Q. (2014). Linking perceived organizational support with employee work outcomes in a Chinese context: Organizational identification as a mediator. European Management Journal, 32, 406–412.

Shore, L. M., Tetrick, L. E., Lynch, P., & Barksdale, K. (2006). Social and economic exchange: Construct development and validation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(4), 837–867.

Shore, L. M., & Wayne, S. J. (1993). Commitment and employee behavior: Comparison of affective commitment and continuance commitment with perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(5), 774–780.

Singh, S., David, R., & Mikkilineni, S. (2018). Organizational virtuousness and work engagement: Mediating role of happiness in India. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 20(1), 88–102.

Sison, A. J. G., & Ferrero, I. (2015). How different is neo-Aristotelian virtue from positive organizational virtuousness? Business Ethics: A European Review, 24(S2), S78–S98.

Sulea, C., Virga, D., Maricutoiu, L. P., Schaufeli, W., Dumitru, C. Z., & Sava, F. A. (2012). Work engagement as mediator between job characteristics and positive and negative extra-role behaviors. Career Development International, 17(3), 188–207.

Tsachouridi, I., & Nikandrou, I. (2016). Organizational virtuousness and spontaneity: A social identity view. Personnel Review, 45(6), 1302–1322.

Tsachouridi, I., & Nikandrou, I. (2018). Organizational virtuousness and employee outcomes: The role of psychological safety and pro-social motives. In A. Stachowicz-, Stanusch & W. Amann (Eds.), Academic social responsibility. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., Bommer, W. H., & Tetrick, L. E. (2002). The role of fair treatment and rewards in perceptions of organizational support and leader–member exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 590–598.

Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., & Liden, R. C. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 40(1), 82–111.

Funding

The study has received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

It was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tsachouridi, I., Nikandrou, I. The Role of Prosocial Motives and Social Exchange in Mediating the Relationship Between Organizational Virtuousness’ Perceptions and Employee Outcomes. J Bus Ethics 166, 535–551 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-04102-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-04102-7