Abstract

While much of the empirical accounting literature suggests that, if differences do exist, Big Four employees are more ethical than non-Big Four employees, this trend has not been evident in the recent media coverage of Big Four tax practitioners acting for multinationals accused of aggressive tax avoidance behaviour. However, there has been little exploration in the literature to date specifically of the relationship between firm size and ethics in tax practice. We aim here to address this gap, initially exploring tax practitioners’ perceptions of the impact of firm size on ethics in tax practice using interview data in order to identify the salient issues involved. We then proceed to assess quantitatively whether employer firm size has an impact on the ethical reasoning of tax practitioners, using a tax context-specific adaptation of a well-known and validated psychometric instrument, the Defining Issues Test.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD 2008) study of the role of tax practitioners in tax compliance recognises that practitioners play a vital role in all tax systems, helping taxpayers to understand and comply with their tax obligations in what is acknowledged as an increasingly complex world of regulation. However, there has been a growing concern in recent years about the ethical behaviour of tax practitioners (Shafer and Simmons 2008). Many firms in the USA have been investigated for facilitating tax avoidance (deemed aggressive or unacceptable by revenue authorities) through the marketing of questionable tax shelters (Herman 2004; Johnston 2004; Scannell 2005) and companies, driven by their top executives, are often accused of using ‘tax havens’ or tax shelters for the primary purpose of avoiding, or indeed, evading their tax obligations (Godar et al. 2005; Dyreng et al. 2007; 2010; Wilson 2009; Sikka 2010). The KPMG tax shelter fraud case in the USA is evidence of the involvement of tax professionals in such approaches (Sikka and Hampton 2005; Sikka 2010), and further evidence that this issue remains relevant comes from the 2012 cases of Starbucks, Amazon, Google and Facebook, highlighted in the British press (see, for example, Barford and Holt 2012), with company executives being interrogated by the UK government’s Public Accounts Committee as to why their companies have allegedly paid little or no corporation tax to the UK revenue authorities. Tax avoidance has been included in the tax literature as one of the dimensions within the broader domain of tax ethics (Frecknall-Hughes and Moizer 2004; Frecknall-Hughes 2007) and aggressive tax avoidance was specifically referred to by the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer in his 2012 Budget speech as being ‘morally repugnant’ (Krouse and Baker 2012). Less tax revenue means reduced provision of public goods and services (e.g. unemployment benefits, hospitals, policing, roads, etc.) or more borrowing by national governments to fund these activities. Therefore, those involved in devising and promoting tax avoidance schemes can be seen as depriving society (especially the needy) of those goods and services, or burdening future generations with increased repayments, both of which are unethical. Shafer and Simmons (2008) suggest that some tax advisers have abandoned concern for the public interest or social welfare in favour of commercialism and client advocacy, and go so far as to suggest that tax practitioners do not believe strongly in the value of ethical or socially responsible corporate behaviour.

Within the accounting literature, one of the variables which has been examined in the context of ethics has been firm size. Numerous studies (e.g. Loeb 1971; Pratt and Beaulieu 1992; Ponemon and Gabhart 1993; Jones and Hiltebeitel 1995; Jeffrey and Weatherholt 1996; Eynon et al. 1997) provide evidence of a link between accounting firm size and ethics, although not all studies have found such a link. Most of the literature (reviewed in more detail below) finds that where firm size does have an impact on ethics in an accounting context, accountants/auditors from the Big Four firms are more ethically sensitive or behave in a more ethical manner than accountants/auditors working in smaller firms.

Most tax practitioners also work for firms rather than as sole practitioners, very often in a separate tax department within a firm of accountants. There has, however, been no direct empirical exploration to date of the relationship between firm size and ethics in tax practice. One might argue that the link between firm size and ethics in a tax context would be no different from the link found within the accounting domain. However, such an argument fails to recognise the differences between tax practitioners and other finance professionals, articulated eloquently by Bobek and Radtke (2007, p. 64):

The ethical environment facing tax professionals is of particular interest because a tax professional’s role is markedly different from that of an auditor. Auditors are required to be independent of their clients, while tax professionals are required to be advocate for their clients. Due to this advocacy role, tax professionals are more likely to face ambiguity in determining when they have crossed the line between being an advocate for their client and supporting an unethical position.

Furthermore, while the accounting literature would suggest that Big Four employees are more ethical than employees working within smaller firms, this difference has not been reflected in the media coverage of tax avoidance schemes which seems to focus (negatively) on the tax behaviour of multinational companies which are advised by Big Four firms.

There are several reasons why there may be differences in the ethical approach or behaviour of tax practitioners working in Big Four firms and those working in smaller practices. The client profiles of Big Four firms are completely different from those of small firms, and tax aggressive practices may be driven by clients with particular profiles. The media has focused recently on the tax reporting of certain large multinational companies, giving the impression that tax avoidance is more dominant in large companies. Ethical differences may arise because the rigid reporting structures in place within large tax practices mean that any individual practitioner, faced with an ethical dilemma, does not make a decision without the support of hierarchical structures and expert colleagues, whereas small firm practitioners must rely more on their own ethical integrity. Big Four firms may be more mindful of their reputation than smaller firms, leading to different approaches to ethics. Perhaps tax practitioners with a particular approach to ethics are more attracted to work in Big Four firms, either as a result of self-selection or recruitment policies, or there may be a difference in the manner in which tax practitioners are socialised into firms of different sizes. Differences in the approach to internal training within firms of different sizes may also lead to differences in the approach to ethical dilemmas.

On the other hand, regardless of employer size, tax practitioners are typically qualified accountants or lawyers and are therefore members of professions governed by codes of ethics which make no distinction between employer firm size in terms of ethical standards. The professional training undertaken by practitioners to qualify to undertake tax work does not differ according to firm size, though several different professional institutes provide tax training. Tax practitioners typically undertake two distinct categories of work (tax compliance and tax consulting or planning work), regardless of whether they work in a Big Four firm or non-Big Four firm. While client profiles and the monetary value of transactions and fees may differ significantly, the inherent nature of the work is uniform. The current media focus on the tax reporting behaviour of multinational companies may simply be a function of the size and visibility of multinationals rather than any genuine difference in tax reporting behaviour (i.e. perhaps the tax behaviour of the indigenous clients of small tax practices is simply not interesting enough in terms of quantity and ingenuity to sell newspapers). Practitioners working in small firms may move to the Big Four, and vice versa, creating a cross-fertilisation effect which may mitigate any differences in ethical culture according to firm size. Smaller firms may be just as conscious of robust reporting structures and seeking expert advice as Big Four firms and may develop mechanisms to ensure their size does not serve as a disadvantage in these areas. Finally, reputation is important regardless of the size of firm and perhaps even more so for small firms operating in regional areas.

In the context of the importance of tax practitioners in the tax compliance process and their role as designers and promoters of tax avoidance structures, both the ethical dimension of tax practice and the ethical orientation of tax practitioners working in firms of different sizes are worthy of focused examination. A comprehensive understanding of how tax practitioners from different sized firms approach dilemmas may assist when devising strategies to address identified deficiencies in ethical behaviour. Similar to the situation in accounting (see, for example, Cooper and Robson 2006), it is also worth noting that tax practitioners from Big Four practices contribute significantly more time and resources to the tax professional bodies, thereby exerting more influence on tax professionalisation, education, regulation and policy. If Big Four tax practitioners perceive ethics in tax differently, and indeed approach ethical dilemmas in a different manner from non-Big Four practitioners, the profession may not be adequately serving or regulating all its constituents and may not be educating all practitioners in an appropriate manner when it comes to ethics in tax.

This research makes a unique contribution to knowledge in this area by focusing on and exploring the impact of firm size on ethics in tax, using both qualitative and quantitative methods. The remainder of this paper is laid out as follows. The second section examines the prior literature on accounting firm size and ethics and looks at the recent work that has focused on ethics in tax practice. Research questions and testable hypotheses derived from the literature review are set out at the end of this section. The third section outlines the research methods [interviews and the use of the Defining Issues Test (DIT) for a quantitative measure of moralFootnote 1 reasoning], while sections four and five set out, respectively, the interview findings in relation to firm size and a comparison of the moral reasoning scores obtained from the DIT. The last section offers conclusions to the paper. Our findings overall indicate that tax practitioners recognise that the ethical issues faced by large international firms and smaller, locally based tax practices are different and may be dealt with differently, but do not necessarily lead to a different outcome ethically. Furthermore, quantitative analysis suggests that the moral reasoning process of tax practitioners working in Big Four firms is not significantly different from that of practitioners working in smaller firms.

Firm Size and Ethics

The employer firm has been identified in several studies as a potentially important influence on ethical decision making (Burns and Kiecker 1995; Hume et al. 1999; Cruz et al. 2000; Yetmar and Eastman 2000). As mentioned above, most tax practitioners work for accounting firms, and these firms vary in size. It is evident from the introduction that tax practitioners working for the Big Four accounting firms have been implicated in the on-going controversy over tax avoidance schemes. There have been numerous studies which provide evidence of a link between firm size and ethics in terms of accounting/audit, although not all studies have found such a link. For example, Loeb (1971) found that accountants in large public accounting firms were more likely to behave ethically than accountants in smaller firms. Eynon et al. (1997) report that accountants from small firms have significantly lower levels of moral reasoning than accountants working in large firms. More recently, Pierce and Sweeney (2010, p. 80) found that firm size was significantly related to ethical judgement, ethical intention, perceived ethical intensity and perceived ethical culture. Overall, in comparison with smaller firms, trainee accountants “from medium-sized firms had lower ethical views and respondents from Big 4 firms [had] higher ethical views”. However, Sweeney and Roberts (1997), investigating the effect of firm size on auditor independence judgements, found that auditors from larger firms were no more likely to comply with independence standards than auditors from mid-size and small firms.

DeAngelo (1981) suggests that larger audit firms have more to lose from a failure to remain independent because of having a greater number of clients, resulting in larger firms demonstrating more independence. Pratt and Beaulieu (1992), in their summary of the differences between small and large firms, suggest that large firms have more rigid control systems than smaller firms. Ponemon and Gabhart (1993) propose that team auditing, peer reviews and affiliation with colleagues and superiors may serve to moderate unethical behaviour in larger accounting firms. Ethical development is said to proceed to higher levels when there is organisational support and where the employer provides ethics training (Jones and Hiltebeitel 1995). Smaller firm practitioners are less likely to have these enabling factors present in the work environment.

Although tax practitioners may work both within the Big Four and smaller firms, there has been little work which examines the effect of firm size as a specific variable in terms of ethics, and, as noted earlier, tax practitioners have an advocacy element to their role which provides a different context to accounting/audit. Ayres et al. (1989) examined whether practitioners would take a pro-taxpayer or pro-government stance in an ambiguous tax case and reported no difference in tax professional judgements across firm size. Carnes et al. (1996) found that the level of tax professionals’ aggressiveness did vary depending on firm type, with the then non-Big Six practitioners being more aggressive in scenarios where pro-taxpayer positions were likely to be taken, while Big Six practitioners were found to be more aggressive in cases of high ambiguity. However, the differences were only marginally significant. They posit that differences in training (in-house vs external), clientele type and clientele size may account for differences in aggressiveness. Yetmar and Eastman (2000) studied the ethical recognition ability of tax practitioners in Big Six firms and in non-Big Six firms. They found significant ethical recognition differences between tax practitioners from Big Six and non-Big Six firms—Big Six practitioners being more ethically sensitive (i.e. they were more likely to recognise that there were ethical implications involved in tax scenarios). Tax practitioners from large firms (classified as Big Four and international/national) rated the ethical environment of their firms more highly than participants at smaller firms in Bobek and Radtke’s study (2007).

Given that tax avoidance remains a salient issue in the economy, it is appropriate to explore firm size in more depth than has been undertaken in the literature to date. While there has been some exploration of tax practitioners’ perceptions of their ethical working environment (see, for example, Marshall et al. 1998; Bobek and Radtke 2007; Bobek et al. 2010), firm size has not been investigated as a primary variable. In order to explore the salient issues that might make the ethical environment of firms of different sizes dissimilar, it was therefore necessary to examine the issue of firm size and ethics in tax initially in an exploratory manner, with the relevant research question being: what are the issues pertaining to firm size that impact on ethics in tax practice? A qualitative approach was taken to this phase of the research, which is outlined in more detail below.

However, in order to explore whether there is a difference in the ethical approach of tax practitioners from different firm sizes, it was also necessary to find a way in which the ethical approach of tax practitioners could be measured objectively. A recent paper by Doyle et al. (2013) examined the cognitive ethical reasoning of tax practitioners using an objective measure called the DIT. (For a review of the use of the DIT and its continuing relevance in the wider domain of accounting ethics research, see Bailey et al. 2010.) The authors found significant differences in the cognitive ethical reasoning of tax practitioners in a tax context when compared with a social context, with lower levels of reasoning being used in a tax context. The practitioners’ levels of cognitive ethical reasoning were not different from non-tax specialists in the social context, but non-specialists did not show a drop in the levels of reasoning used when they moved to the tax context. Thus, tax practitioners are not less ethical per se than non-specialists, but their reasoning is at a lower level in their professional context. The Doyle et al. (2013) study did not examine firm size as a variable. However, the research instrument used illustrates how cognitive ethical reasoning can be measured in both a social and tax context, providing us with a means by which differences in the ethical approaches of tax practitioners working in Big Four firms and smaller firms can be examined objectively. Following this approach allows us to examine whether tax practitioners with a particular approach to ethics are more attracted to work in Big Four firms, either as a result of self-selection or recruitment policies, or whether there are differences arising from the manner in which tax practitioners are socialised into firms of different sizes.

Research Objectives and Hypotheses

For the interview study (phase 1) the research objective was to understand tax practitioners’ perceptions of the relationship between firm size and ethics. This is useful in providing an ‘inside view’ of the issues and potential reasons for differences between firms, to complement and inform the outside view provided by tests of ethical reasoning in response to particular problems provided by the researcher.

The objective of the second phase of the study was to investigate whether evidence existed of a difference in ethical reasoning between practitioners in Big Four and non-Big Four firms. On the basis that the professional training and education of tax practitioners in the private sector is largely uniform in IrelandFootnote 2 (there is only one tax institute and it awards the only professional qualifications in tax), a potential basis for differences between Big Four and non-Big Four practitioners could be socialisation effects—differences caused by something in the firm environment that has an effect on reasoning. For example, Big Four firms conduct their own internal tax training (other than for the professional qualification in tax) rather than availing themselves of the generic training offered by the Irish Tax Institute, which practitioners from smaller firms would typically utilise. The hierarchical reporting structures are likely to be different in large firms from those existing in smaller ones. It has also been contended that smaller firms are more financially reliant on and socially close to clients, so may be under pressure to act in their interests to a degree not present in the Big Four firms.

Given that the literature from the accounting context discussed above suggests that Big Four firms may be more ethically conscious, our first research hypothesis is

Hypothesis 1

When considering tax practice context ethical dilemmas, Big Four tax practitioners will employ higher level ethical reasoning than non-Big Four practitioners.

It is possible, however, that individuals with different levels of moral reasoning are attracted to particular types of firm: persons with a high level of moral reasoning may, for example, choose to join a Big Four firm because they perceive this as more fitting with their own orientation. If this should be the case, we would expect differences in the moral reasoning levels of Big Four and non-Big Four practitioners in a social as well as a tax context. However, if differences in moral reasoning result from socialisation within a tax context, we would not expect to find differences in Big Four and non-Big Four practitioners’ moral reasoning in a social context (but only in the tax domain). Testing for differences in the moral reasoning scores of Big Four and non-Big Four participants in both a social and tax context allows us to make this distinction and to check whether differences in the level of moral reasoning might arise before an individual enters tax practice (i.e. owing to individuals with a particular ethical orientation self-selecting into the Big Four) or as a result of socialisation within the tax context (socialisation effects within the employment context). We will initially take the view that there will be no difference in the social context ethical reasoning levels of practitioners working in different types of firm leading to our second research hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

When considering social context ethical dilemmas, Big Four tax and non-Big Four practitioners will employ similar levels of ethical reasoning.

Research Methods

Phase 1 (Interview Study of Practitioners’ Perceptions)

As mentioned above, the first phase of this research was exploratory. The aim was to examine the perceived impact of firm size on ethics in tax practice from the perspective of tax practitioners. In order to gather rich and detailed data, face to face interviews with tax professionals were deemed the optimum research method. Using a cross between purposive and convenience sampling, potential interviewees were identified by prior personal knowledge, professional contact or recommendation.

Tax partners were particularly targeted for interview on the basis that their range of experience was likely to yield richer data than that of tax practitioners at more junior levels, and they were more likely to have encountered ethical dilemmas. Consequently, ten potential interviewees representing practitioners from a wide range of firm sizes and employment categories were contacted by e-mail, given information on the broad nature of the research, assured as to the confidentiality of names and firms, and asked if they would contribute their time on a voluntary basis. All ten agreed to be interviewed.

The ten interviewees comprised practitioners from Big 4 firms (n = 4), a middle tier firm (n = 1), a small accounting practice (n = 1), a legal practice (n = 1), a large multinational company (n = 1), a sole practitioner (n = 1) and a director within a relevant professional institute (n = 1). Interviewee title, firm or company profile, region and how they are referred to in the paper are set out in Table 1. Given the inherently sensitive nature of taxation ethics, which practitioners are often reluctant to discuss, this represents a significant number of interviews.

The interviews were semi-structured with open-ended questions and probes used to elicit each participant’s views. All participants consented to interviews being tape-recorded. The narrative data (audio-tapes) were converted into partly processed data (verbatim transcripts) before coding and analysis. Data were coded using typical template analysis procedures (King 2004, pp. 256–270). In reporting interview findings, we include extensive quotes from our interviewees “to allow the reader to hear the interviewees’ voices…[and to]…allow the richness of the data to shine through” (O’Dwyer 2004, p. 403). A paper based on the link between ethics and risk management (Doyle et al. 2009a) has been published by the authors, based on findings from these same interviews. However, the issue of firm size was not explored in that earlier paper.

Phase 2 (Comparison of Moral Reasoning Scores)

Cognitive developmental psychologists believe that before an individual reaches a decision about how and whether to behave ethically in a specific situation, ethical or moral reasoning takes place at a cognitive level. The psychology of moral reasoning aims to understand how people think about moral dilemmas and the processes they use in approaching them (Kohlberg 1973; Rest 1979b).

Rest (1979a) developed the DIT to measure moral reasoning using social context dilemmas. It is a self-administered, multiple-choice instrument. Rest (1979b) developed the instrument based on an interpretation of the stages in Kohlberg’s stage-sequence theory (Table 2). The test measures the comprehension and preference for the principled level of reasoning (Rest et al. 1999). For more detail on Kohlberg’s stage-sequence theory and the DIT, see Doyle et al. (2009b).

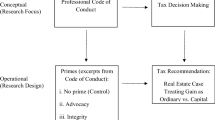

The second phase of the research aimed to examine the relationship between firm size and ethical reasoning in a quantitative manner by using a 2 × 2 quasi-experimental design comparing the moral reasoning of Big Four tax practitioners with those from other firms in tax and social context ethical dilemmas. The data for this phase of the study were taken from a larger study of tax practitioners’ moral reasoning, some findings from which have been published in Doyle et al. (2013). However, the relationship between firm size and moral reasoning has not previously been considered. The test of reasoning in social dilemmas uses the short-form (three-scenario) DIT. Participants taking the DIT are presented with ethical dilemmas stated in third-person form. They are asked to rate the importance of 12 considerations relating to the dilemma, indicating how important each is (in their opinion) in making the decision described. The 12 considerations link to the stages of cognitive moral development described in Table 2. The participant is then asked to select the four considerations that he/she considers to be of most importance and to rank these in order. The first of the DIT scenarios, ‘Heinz and the Drug’, is set out in “Appendix 1” as an example.Footnote 3 Scoring the instrument results in a single measure known as the ‘P’ score (standing for ‘principled moral thinking’) for each participant (Rest 1994). A higher P score implies a lower percentage of reasoning at lower levels. For the tax context, we use a tax-specific version of the DIT, the TPDIT, which uses three tax context-specific scenarios. The development of the TPDIT is described in Doyle et al. (2009b). The TPDIT was developed to preserve the psychometric characteristics of the original test and to match it as closely as possible to the three scenario version of the DIT. The difference in the TPDIT, as compared with the DIT, lies in the nature of the dilemmas presented to participants and the related ‘items for consideration’ following each dilemma, all of which are tax practice-related. An example of one of the dilemmas included in the TPDIT is set out in “Appendix 2”.Footnote 4

Participants completed the DIT and TPDIT in a single instrument, with two counterbalanced versions being used to allow any order effects to be identified and controlled for. The order of individual scenarios within the DIT and TPDIT was not varied, in line with practice for the DIT. Both versions contained a demographic questionnaire at the end.

In 2009, 384 tax practitioners in Ireland were contacted using a combination of random, convenience and snowball sampling techniques and were asked to participate in the study. The practitioners worked in a range of tax-related roles in Ireland, including private practice and the revenue authority. There was a 39 per cent response rate (150 completed instruments). Following checks for full completion of the scenario-based questions and the subject reliability checks described in the DIT manual (Rest 1986a), a sample of 101 instruments was available for analysis. For this study, we focus on those practitioners in private practice, where the advocacy aspect of the role would be present, and so do not include practitioners working in the public sector either with the revenue authority or in education. This resulted in the elimination of a further 27 instruments, leaving a sample of 74 respondents.

Interview Findings on Firm Size

This section outlines the salient themes that emerged from interviews with tax practitioners about their perceptions of the impact of employer firm size on ethics in tax practice.

The Combined Context—Ethics, Compliance, Risk and Reputation

From interviewees generally, the impression conveyed is of a working environment for tax where ethics, compliance and risk are inextricably intertwined in relation to terminology used, and where ‘getting it wrong’ has adverse consequences for reputation.

…you may need to be a bit more specific about what you mean by ethics because sometimes people would automatically say no but if you drill down into the thinking, they are considering ethical stuff, they maybe just don’t call it ethics.—Institute Official

There was confusion among interviewees about the role that ethics play in tax, if any. Certain interviewees boldly stated that ethics have no place in tax practice—or indeed, business, for example:

Ethics is pretty much at the lower end of the spectrum in terms of what the purpose of a tax adviser is.—Tax Director

I suppose the question that you are asking is to what extent does ethics or morals come into it when you are making a decision and I would say probably not that much to be honest.—Tax Partner 2

It is not immediately apparent…I’ll be perfectly honest with you, that ethics and tax would go hand in hand…—Tax Partner 4

Principle-based issues, such as making a contribution to the common good, were not in the definitions generally. Indeed one participant indicated that the link was not conceptualised by practitioners, and might be resisted.

To a certain extent there is really no ethics in tax…. I don’t think that many tax people would feel that if I save my clients tax, patients die in hospital or anything like that. I think they don’t think in those terms at all. I think they will always resist the view that [that] kind of relationship [exists] between the common good and what they do.—Tax Partner 2

The issue was more about whether practitioners and their clients are legally compliant, rather than ethical, and a pragmatic framework employing the language of rules and risk managementFootnote 5 was used to deal with issues.

If I was to talk to a client, I wouldn’t use the words—‘ethically you have to pay tax’. I would be putting it to him, the risk he puts himself and his business and his family and his employees, by not being tax compliant. If you start talking to a client about ethics, he thinks you are God and you have a Revenue Commissioner’s stamp at the back of your head. Talk to them about risk and you are giving them good advice for which they will thank you.—Managing Partner

…I don’t think tax people think of it in terms of ethics. They think of it in terms of aggressive or less aggressive. Risk management also has a lot to do with it actually.—Tax Partner 2

Being seen not to overstep certain bounds is important as regards reputation, which has clear links to ethics and risk.

…because if this ever does come home to roost, that’s my reputation. So in fact, if I am honest, it’s more a reputational issue than a moral issue. If I am worried that if I am seen to be part of a transaction that I actually don’t believe is right, that my reputation with the Revenue will suffer as a result and I don’t want that to happen so maybe it is reputational risk rather than morality.—Tax Partner 2

Examination of different sized firms, that is, Big Four versus non-Big Four, revealed that ethics, compliance and risk management have different impacts. These can often be considered in terms of different aspects of ‘distance’, determined by different operating circumstances and/or different types of clients. These are considered below.

The Concept of ‘Distance’ Created by Internal Regulations

Big Four practitioners have in place a multiplicity of rules and regulations designed to deal with ethical situations that might arise.

Our ethics is bound up with our code of conduct which deals with everything about dealing with people, dealing with people internally, respect, teamwork and all that rather than ‘is this right or wrong?’.—Tax Partner 1

The presence of so much internal regulation means that there is therefore less need (and opportunity) for individuals to think through a dilemma personally to reach a decision on what to do. The rules are designed to deal with dilemmas for them. This might stultify personal ethical decision making and distance individuals from it, but has the benefit that a global organisation will apply the same procedures to similar situations wherever they arise, so a consistent approach is adopted.

For example if they come up with a tricky client situation they will automatically start thinking, what is the risk here? Are there company guidelines about this, best practice guidelines?—Institute Official

Those in smaller firms felt the decision was more theirs.

I think you think about ethics more in a small practice. You are at a distance in a bigger practice.—Sole Practitioner

However, having to develop personal responsibility in smaller firms was seen in a positive way.

Better training in a smaller firm. You are thrown in at the deep end and you have to learn on the job and take responsibility for yourself.—Managing Partner

The benefit derived from this was recognised also by large firms, as the rules-/risk-based approach means that people often never come near a dilemma, because it has been ‘risk-managed’ away.

I would prefer if people’s moral compasses were activated early on because I would much prefer people responding the right way from an intuitive or instinctive reason rather than ‘chapter two of the risk management manual tells me I must do the following’. So could we end up with a situation where there are people coming up through the system that are never exposed to the moral dilemma? Yes. Do I worry then that there may be a fall in ethical standards? No because I think the risk management boundaries are tighter. But do I think it is a good thing? No because as I say I would prefer practitioners to have an inner intuitive understanding as to what is right and wrong rather than a mechanical regurgitation of a factual situation.—Tax Partner 1

…the morality boundaries are out there but the risk management boundaries have moved in even closer. So you never get near the moral boundaries because you hit the risk management boundaries.—Tax Partner 1

Support Structures

The rules-/risk-based approach of Big Four and international non-Big Four practices forms part of a wider support structure, which also includes specialised knowledge provision, supportive colleagues and so on. This may not be as readily available to practitioners working in a smaller practice or in isolation as a tax director working in industry. In the event of a dilemma arising that is not covered by the ‘rules’, the availability of the support structures again means that an individual tax practitioner would very rarely have to depend on his/her own judgement to resolve an ethical dilemma, as further advice could be sought if a situation was unclear.

If you do have an ethical dilemma in a big firm you would look for advice and then it really isn’t an ethical dilemma any more because you have given it out and you’ve got an answer.—Tax Partner 2

The absence of this support in a smaller practice and within a company places more emphasis on the individual’s ethical reasoning.

You could have two people of the exact same ethical standard working in totally different firms and the person working in the big firm with all the support, will get it right 99–100 per cent of the time and the sole practitioner might only make the right call 60 per cent of the time but that is not to say he is less ethical but there is so much more put back on him in terms of making an ethical judgement so there is a huge difference there.—Tax Partner 3

You look at the Big Four and you have all these tax knowledge centres…You’ve got peer reviews; you go to different people if there is something that you are not sure of or whatever. You can get so many different views and opinions on it and so much back-up and there really is sometimes very little risk because… you follow the whole thing up along and you have an answer given to you… You don’t have that kind of backup. It’s like someone ripping off all your clothes and sending you out onto the street because you had all the support structures of people working under you, people above you with more experience that you can bounce things off, technical resources…versus when you come over here and you have to think on your own two feet. You don’t have that kind of back-up.—Tax Director

One of the small firm tax practitioners referred to his/her attempt to compensate for this dearth of support structures by becoming part of a sole practitioners’ support group.

We have a discussion group, about six or eight of us that meet…we talk about things…I would feel very isolated without it.—Sole Practitioner

Another aspect associated with a firm being large is that it has in-house expertise and is able to run internal training courses for its employees, thereby ensuring that both discipline-specific knowledge and awareness of industry regulations are up to date. Smaller firms are usually not in a position to be able to afford this luxury.

We invest a lot on educating people as to what the regulations are. There could be sole practitioners out there who are ignorant as to some of the regulations. You then have practitioners who have no tax specialist expertise, yet they are doing tax returns and making judgement calls as to the taxation, taking deductions and allowances and so on.—Tax Partner 3

We can’t afford it. You are thrown into the pool…We don’t have what they have in the bigger firms in terms of sending them off on a course for a week. We don’t have that luxury.—Managing Partner

I can’t fork out €600 for a few hours of a course.—Sole Practitioner

Another view that was expressed was that trainees are exposed to far better ‘on the job’ training in a smaller firm, where they are ‘thrown in at the deep end’ and must acquire skills rapidly to survive and progress. They are also exposed to a far greater range of work than trainees in large firms which tend to have very specialised departments. However, the perception by larger firms is that smaller firms will make mistakes that they want to hide.

I suspect that the further down the size of organisation you go, the likelihood of something being buried [i.e. mistakes being covered up] is higher.—Tax Partner 1

Proximity to Clients

A particular characteristic that makes smaller practices attractive to clients is their ability to offer a personal service. Clients will interact with the same staff on a regular basis over a long period, facilitating the development of a strong working relationship, which generates a degree of proximity. Practitioners will know the client’s business well and are accessible.

I was only ten months as a partner in XXX [a large practice], clients couldn’t take it. They were being diverted away from me. And you get to know a client very well. They are comfortable with you. You have a bit of banter with them. They know you will look after them and I know their businesses inside out.—Managing Partner

I think the relationship with the client can be fundamentally different depending on whether you are a sole trader or a big firm and I think it’s simply because I think the sole traders create a relationship basis… because that is what they have to offer. They mightn’t have the greatest expertise to offer. They’re a bit of a GP [general practitioner] because they have to cover all things. But… they’re accessible, they’re always at the end of the phone and they treat you as if you’re the best client in the world, ever. And they do everything for you. Whereas the big…companies don’t have to do that. Why? Because the loss of you isn’t such a big deal.—Tax Partner 4

However, there is also a potential disadvantage if such relationships with clients result in the client having a negative influence on the tax practitioner’s ethical position.

I don’t want them to be my friends. The minute that they are my friends, things will have to change. I understand that. Because you might do some things differently for a friend than you would for a client.—Tax Partner 4

This problem may be compounded if the tax practitioner operates in a regional area where he/she is likely to encounter the client on a regular basis in a social capacity, and, indeed, where clients of the tax practitioner may know each other and have business dealings with each other.

When you are dealing with an owner-managed business, small manufacturing business, a doctor or a chemist, that is a one on one relationship. Chances are you will be a member of the golf club and they will, you’ll meet them in restaurants that you will go to. So you will know them…And maybe there will be a willingness, in those situations, to turn a blind eye.—Tax Director

…you know a client wants to do the wrong thing, forgetting about scale for the moment, so you tell the client that they can’t do it. Even if the client says ‘I’m going’, it doesn’t matter because you will be lauded for doing the right thing within the firm…In a small firm you don’t have support in facing down the client on an issue. It’s much more of a personal confrontation…In a big firm you can always say ‘look it’s not me that is telling you this, this is the whole firm telling you this, my hands are tied, I have to tell you, you can’t do it’. You don’t have that sort of opt-out in a small firm where you have to tell the client, ‘this is my judgement, this is my view, you can’t do it.’—Tax Partner 3

I think that the pressures on a lot of the smaller businesses to do what the clients require of them is much greater than in the larger practice.—Risk Management Partner

Some larger firm interviewees considered that if a tax practitioner has a close relationship with a client and knows him/her in a personal capacity as well as in a business capacity, it is possible that the practitioner’s ethical stance may be influenced by the client more significantly than in a case where there is no personal relationship with the client. However, the smaller firm practitioners interviewed did not share this view.

There isn’t one client here that would frighten me. I’m friends with the whole lot of them. Some I’ve known for 27 years. I lose very few clients. They know what they get here. What they see is what they get. They will never be misguided.—Managing Partner

You probably spoon feed them more but I don’t know if that would stretch, because I always have the view that it is a slippery slope. If I do it once then where is the cut-off point? So I just always observe the practice that if you are doing something wrong, then I just can’t be part of it.—Sole Practitioner

Financial Dependence/Closeness

Typically, a sole practitioner will have a client portfolio consisting of a certain number of small clients. However, he/she may be financially dependent on the fees paid by a small number of large clients, which may give those clients the ability to influence the ethical behaviour of the practitioner.

And then they may be overly reliant on certain large accounts and that may influence their decisions when it comes to tough calls.—Tax Partner 3

Bigger firms would find it easier to call the shots with a client than smaller firms. Let’s take a client that pays you €20,000 a year to do something for him and your turnover is a million quid, that’s a big client. You take XXX firm and it’s a €20,000 a year fee and they’re turning over €20 million…One client leaving at €20,000 from XXX doesn’t matter…whereas one guy leaving from Joe Bloggs himself, it could be everything to him.—Tax Partner 4

I think that certainly, a sole practitioner with, say, his largest client that makes up 30 per cent of his fee income, he turns over 60,000 a year and this guy pays him 25 grand, and he finds that [a mistake in a prior year tax return prepared by him], he won’t bring it up—Managing Partner

However, this concern was predominantly expressed by the large firm practitioners. It would be equally fair to say that large firms may have very large clients, who contribute very large fees, and while there are professional guidelines for auditors as to how much fee income should be derived from one client or group, the situation as regards tax fees is less certain. The Enron case provides clear evidence that dependency situations can also arise for large firms. While the smaller firm practitioners did acknowledge that financial dependence was an issue for other firms, they denied it had an influence on their own practices.

Our largest client, who is a sizable property developer, is a great friend of mine. I would have murder with him about his tax. Eventually he will pay.—Managing Partner

Client Profile

Smaller practices have a different client profile from larger practices. They predominantly deal with owner-managers and high net worth individuals rather than multinational companies, which are typically advised by the larger firms. Interviewees were in agreement that these two broad categories of client had vastly different perceptions of tax.

Look at the client base. I mean my client base, at the moment is primarily multinationals, various Irish companies who are semi-state,Footnote 6 a couple of educational establishments and a couple of tax based property deals. Many of those cases, they just don’t want to be on the wrong side of the law, whatever it is.—Tax Partner 1

You probably spoon feed [small clients] more…I have a client and he is always last minute in terms of returning on the last day and he was always and ever thus…—Sole Practitioner

They would be from areas in the country where they wouldn’t be used to paying tax. One business is now telling me that in their village, they are the only ones paying this amount of tax.—Managing Partner

It is recognised that multinational companies have to be cognisant of legislation and regulation such that their main tax strategy should be to structure operations and transactions in order to minimise tax but never to be perceived as crossing ethical boundaries, wherever and however they may be set. It follows that the tax practitioners they engage must have a reputation for being ethically unsullied. The recent case of Starbucks, however, particularly evidences that what is legal is not always perceived as ethical and that opinions may change as a result of how certain situations are perceived, presented or reported.

It was stressed by certain Big Four interviewees that, as their firms were global practices, their operating strategy was driven by the expectations of global clients and that such an expectation resulted in a common standard which was then also applied to their smaller, locally based clients. With global clients, it is important that the firms present themselves as fully compliant with all legislation and regulation, unsullied and professional, with no problems with regard to the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). For a local practitioner with a strong local client base, reputation with high net worth individuals, dealing with property transactions and managing wealth, was far more important.

If you are dealing with a Big Four firm, their reputation is key and certainly in my experience, you’ll find that they will be down to the letter of the law.—Tax Director

One interviewee referred the researcher to the Tax Defaulters listFootnote 7 and observed that very few of the names on the list were Big Four clients.

It was also noteworthy that when a tax practitioner dealt with a multinational company, he/she would be communicating with a financial controller or a chief executive officer (CEO), merely doing his/her job, rather than with the shareholders, whose funds will be used to meet the tax liability.

Let’s take your big multinational again, and let’s take that for the most part you will deal with a financial controller…and the board…A financial controller is in control of money that is not his own, whereas [with] an owner-managed business you are in control of money that is your own. If something costs you €10,000, it’s your money.—Tax Partner 4

You’ve seen when you are dealing with the international clients, you spend more time advising on things to make sure that they are right…Fantastic clients, lots of money, lots of advice, low enough risk. Then you have the guys who are owner-managed and are saying, ‘I want to save tax’. How the heck do you deal with that as a starting point?…The parameters are so different between the two. Your client will drive an awful lot of how you deal.—Tax Partner 4

As with some of the other factors mentioned above that distinguish smaller practices from larger ones, the concern is that practitioners dealing with owner-managers will come under pressure from their clients to behave in a manner that may be less than ethical if that position saves the client more tax. The smaller firm practitioners acknowledged this about other firms but suggested that this did not present a problem for them personally.

We would get people coming to us from other firms, which I would describe as bad firms, in a bit of a mess…we will tidy them up and tuck them back into bed. If they fall out of bed, good luck.—Managing Partner

I have this one lady and she was with this very, very seriously high profile tax accountant years back but he just didn’t file her returns and pay her taxes.—Sole Practitioner

Summary Perceptions as to the Impact of Firm Size on Ethics

The interviews indicate that large firms tend to rely on the internal regulations and support structures to ‘risk manage’ away ethical dilemmas well before they reach the stage of the individual practitioner having to deal with them. They see smaller firms in general as being disadvantaged by the lack of such support structures, and prone therefore to making unsound decisions, which are compounded by the type of clients smaller firms have, creating pressures upon them which the larger firms do not face. However, while smaller practitioners acknowledge the lack of a support structure and the impact of a different type of client, this means that they have to reason from first principles, hence they come to an ethical decision via a different—and more demanding—route, dealing with each issue on a case by case basis rather than applying a pre-defined set of rules. One of the large firms acknowledged that this is, per se, a desirable process. This does not necessarily mean that the end result would be different if both a large firm and a smaller firm practitioner applied their processes to the same issue.

Given the concern with maintaining an unsullied ethical reputation and the obedience to rules, which affects both small and large practitioners (though it appears to be of greater concern for large firm practitioners), the issue here seems less about the good of the client (society at large not even entering the equation), and much more about the tax practitioner’s own reputation and financial position. This would suggest a combination of stage two to stage four reasoning by reference to Kohlberg’s model, rather than principled reasoning. Table 3 summarizes the findings from the interview phase of the study.

Comparison of Moral Reasoning Scores

In this section, the levels of ethical reasoning used by practitioners from Big Four and non-Big Four firms are compared in both social and tax contexts. This provides a comparison of underlying ethical processes and allows for the identification of sources of any differences found (the sort of individuals attracted to different types of firm vs socialisation).

Sample Profile

Of the 74 participants in the sample, there were 36 Big Four participants (49 %) and 38 non-Big Four (51 %). The fact that Big Four firms are extremely large international partnerships, employing numbers of tax practitioners considerably in excess of any other type of firm, distinguishes them from any other type of firm in which tax practitioners may work (whether a law firm or multinational with its own tax department). Demographic information on the two groups is given in Table 4. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the groups (P > 0.1 in all tests).

An analysis of where the practitioners worked showed considerable variety. The details are set out in Table 5.

Practitioners held a wide variety of positions within their employing entities, ranging from tax trainee to partner, as illustrated in Table 6.

The DIT produces a measure of moral reasoning, the P score, which indicates the percentage of moral reasoning taking place at the post-conventional level. In this study, we have two such measures: one for social context moral dilemmas (PSCOREDIT) and one for tax-based dilemmas (PSCORETAX). Although the two types of firm were not significantly different on demographic variables, potential relationships between demographic information (age, gender, education, years of tax experience and seniority of position in the firm) and P scores were explored using multiple regression models (Tables 7, 8) to identify whether any needed to be included as covariates in the statistical model. Previous research has identified that education, age and potentially gender can have an impact on moral reasoning (see, for example, Gilligan 1982; Rest 1986b; Ponemon 1990, 1992; Rest and Narvaez 1994; Shaub 1994; Jones and Hiltebeitel 1995; Tsui 1996; Eynon et al. 1997; Etherington and Hill 1998; Abdolmohammadi et al. 2003). In this context, it is also possible that experience or level in the firm might offer different perspectives on ethical issues.

The regression models included an indicator of the participant group (TPTYPE, set to 1 for Big Four and 0 for non-Big Four), and an indicator of the order of the two contexts in the instrument to control for any order effects (TAXFIRST, set to 1 if the tax based dilemmas were presented first and 0 when the social dilemmas were presented first). Education was classified in terms of whether the individual’s highest qualification was below degree level, at degree level, or at postgraduate level, and dummy variables for below degree level (EDNODEGREE) and postgraduate education (EDPG) were included in the models. Seniority of position within the organisation was classified in terms of whether the individual was below manager level, at manager level, or at above manager level, and dummy variables for below manager (BELOWMANAGER) and above manager (ABOVEMANAGER) were also included in the models. This particular distinction in position level was considered appropriate on the basis that tax practitioners at manager level become responsible for their own portfolio of clients and client issues are most frequently cited as giving rise to ethical dilemmas (see, for example, Marshall et al. 1998).

As can be seen from Tables 7 and 8, none of the demographic variables included in the regression model has a significant effect on either PSCOREDIT or PSCORETAX at the 5 per cent level. Eliminating either years of tax experience or position in the firm from the regression model (on the basis that these variables are likely to be highly correlated) did not result in either variable achieving significance at the 5 per cent level.

Main Model

The research hypotheses were tested using a GLM repeated measures analysis, with the two dependent variables captured by a within-subjects measure CONTEXT (social and tax), with TPTYPE (Big Four or non-Big Four practitioner) as a between-subjects measure. The results of this analysis are shown in Table 9.

As can be seen from the table, TPTYPE (distinguishing Big Four and non-Big Four practitioners) is not significant (P = 0.682) but CONTEXT is (P < 0.001). While both categories of practitioner reason significantly differently in a social versus a tax context, there is no significant interaction between CONTEXT and TPTYPE. The estimated marginal means, set out in Table 10, show that PSCOREDIT and PSCORETAX are different but that this difference is evident for both groups of practitioners, and the relationship between context and practitioner type is clearly illustrated in the interaction graph (Fig. 1).Footnote 8 A MANOVA on both scores with TPTYPE as a between-subjects effect confirmed that the two types of practitioner did not differ significantly from each other in either context (P > 0.1 in both cases).

These results do not support hypothesis 1 but support hypothesis 2. There is no significant difference in levels of moral reasoning in the social context based on firm type, indicating that the two firm types are not attracting individuals with different levels of moral reasoning in general terms. Moral reasoning for both categories of tax practitioner (Big Four and non-Big Four) alters significantly as the context changes from a social to a tax one, with both groups reasoning at a significantly lower level in a tax context than they do in a social one, but there are no significant differences between the groups in this context either. This would support the proposition that socialisation leads to different moral reasoning in the work context, but indicates that this effect does not differ by firm size. The different pressures presented by tax practices of different profiles, identified and discussed by interviewees in phase 1 of the study, do not result in different levels of moral reasoning. It should be noted that these results are robust to the exclusion of legal firm practitioners and practitioners working in industry from all of the statistical models.

The results did not reveal any significant differences in the moral reasoning of males and females. This finding is consistent with the prior literature in accounting, most of which finds no statistically significant difference in moral reasoning between the sexes (Ponemon 1990, 1992; Tsui 1996; Abdolmohammadi et al. 2003). Age does not appear to effect moral reasoning scores. This finding is consistent with Shaub (1994) but not with many other studies that have examined age (Ponemon 1990; Jones and Hiltebeitel 1995; Eynon et al. 1997; Etherington and Hill 1998). Age is sometimes used as a proxy for experience but neither years of tax experience nor hierarchical position within the employer entity were found to have significant effects on moral reasoning scores in either context in this study. The analysis also indicates that education does not have a significant effect on moral reasoning in either context. This is inconsistent with the DIT literature which suggests that levels of formal education account for 30 to 50 % of the variance in DIT scores (Bebeau and Thoma 2003). However, this finding may be due to the fact that there was no significant variation in the educational levels of the participants in comparison to what might be found in the population at large. The finding with respect to hierarchical position in the firm is consistent with much of the research which looks at the effect of position in the firm on moral reasoning (e.g. Ponemon and Gabhart 1993; Etherington and Schulting 1995; Jeffrey and Weatherholt 1996; Bernardi and Arnold 1997; Scofield et al. 2004).

Conclusions

Interviews carried out with tax practitioners in Ireland provided a rich source of information about how firm size is perceived to affect ethics in tax practice. The reluctance on the part of practitioners interviewed to recognise the role of ethics in taxation is interesting and is consistent with the perception that risk management and the preservation of reputation are the key issues of concern, as also indicated in Doyle et al. (2009a). This latter paper generally examined the link between ethics and risk management in tax, but without the specific focus on firm size or its impact which comprise the unique focus and contribution of the present paper.

It was acknowledged by some practitioners that the ethical issues faced by large international firms and smaller, locally based tax practices are different and are typically dealt with differently. However, this does not necessarily appear to lead to a different ethical outcome. Large firms may have different procedures and processes in place by which to address ethical issues, principally using the application of a pre-defined set of internally generated rules and support structures, which preclude the need for any individual within the firm to reason from first principles about any ethical issue which might arise. Others (small firms and industry practitioners) appear to be prepared to reason from first principles, but it is recognised that this might have a positive effect on ethical awareness.

In gathering the perceptions of tax practitioners as to the impact of firm size on ethics, it should be noted that no practitioners admitted to being less than ethical themselves. All interviewees spoke of abstract ‘other practitioners’ in articulating their perceptions of how firm size influences ethics or in giving examples of unethical behaviour. The large firm practitioners in particular perceived that smaller firm practitioners were less ethical as a result of the pressures they were under to maintain and grow their practices. However, the interviews did not uncover any evidence that small firm practitioners were less ethical than large firm practitioners. There is widespread anecdotal evidence within tax practice that the revenue authorities in Ireland and the UK maintain a list of tax practitioners considered to be more tax aggressive than the norm. The tax authorities are said to focus increased attention on the clients of these ‘black listed’ practitioners. Furthermore, this list is said to be populated predominantly by smaller firm practitioners. However, no concrete evidence of this list exists. Furthermore, the impression within the tax profession that smaller firm practitioners dominate this list, with no consideration given to the distribution of tax practitioners between firms of different sizes, serves to illustrate how smaller firm practitioners may be perceived within the profession as a whole. It is a limitation of this research that no tax practitioner identified as unethical was interviewed, and of course, that it is not possible to know who such ‘black listed’ practitioners are. Moreover, interviews were carried out with a relatively small number of practitioners. This needs to be borne in mind, as results are not necessarily generalisable—though this is a limitation affecting most interview data.

When firm size was examined quantitatively as part of the second phase of the study, there was no evidence of a significant difference between the moral reasoning of practitioners working with the Big Four and those working in other private sector tax related roles, for example, smaller firms and in industry. This supports the interview findings. However, there is little evidence of the higher levels of moral reasoning in either large or small firms in the tax context.

All tax practitioners, from both large and smaller firms, reason in a less principled manner when presented with dilemmas in a tax context than when considering dilemmas in a social context. The P scores achieved by tax practitioners in a tax context (mean PSCORETAX 19.234) were very low compared with their P scores in a social context (mean PSCOREDIT 33.018). While the quantitative results do not identify the reasons for the differences in moral reasoning, this may be due to a socialisation effect in private sector tax practice (see Doyle et al. 2013).

The impact of firm size on ethics in tax practice from the perspective of tax practitioners has not been examined in the literature before now and this is, therefore, a significant contribution made by this paper. The paper also advances knowledge by investigating how the ethical reasoning of tax practitioners varies by reference to firm size and context. In addition to its contribution to academic knowledge, this study has significant implications for educators and the tax profession itself.

The knowledge that tax practitioners in both size groups use much lower levels of moral reasoning in a work context than in a social one, and to a similar extent, can inform educators’ approaches to delivering both academic and professional training/education programmes to practitioners from all firm sizes. It will help them to tailor modules or courses to emphasise the importance of ethics in different work contexts and include initiatives to stimulate ethical development in the relevant curricula. Understanding the different ethical issues faced by large international firms and smaller, locally based tax practices facilitates more nuanced training/education which appropriately addresses the needs of practitioners from different firm sizes.

The tax profession, represented by relevant professional institutes, will benefit from being cognisant of the perceptions of tax practitioners with respect to ethics and their level of moral reasoning, particularly in light of the self-regulated nature of the profession and the different approaches required in different environments (risk management in larger firms vs reasoning through ethical dilemmas in smaller firms). Care needs to be taken that the ethical sensitivity of practitioners is not dulled by risk management procedures aimed at avoiding litigation but often hemming in professional judgement. Being aware of the different needs of smaller practitioners is important given that Big Four practitioners contribute more significantly to the tax professional bodies than non-Big Four practitioners, thereby exerting more influence on tax professionalisation, education, regulation and policy. The inclusion of ethical issues from small firms in training may help those in larger firms develop their ethical thinking beyond reliance on risk management, for example, while some aspects of the risk management approaches used in larger firms might provide insights to practitioners in smaller firms. Consideration of the different issues in different sizes of firm will help the professional bodies provide a better service to all their constituents in areas of education, regulation and input into tax policy issues on behalf of members.

This brings us back to the motivation underlying this paper. If the ethical antennae of practitioners, through more effective training/education, can develop greater sensitivity to the different types of issues that generate ethical dilemmas, will this prevent the proliferation of tax avoidance schemes that are perceived as unethical? It is, of course, impossible to predict with any degree of certainty, but a greater ethical sensitivity might encourage the type of practitioners who are willing to develop and promote ‘dodgy’ schemes to consider the impact of such schemes on wider society, that is, to look beyond the tax they save their clients. The fact that all tax practitioners’ P scores are lower in tax scenarios than in social situations supports a need for development of greater ethical sensitivity in tax practice generally.

Notes

The terms ‘morality’ and ‘ethics’ are used interchangeably in the literature on the psychology of moral reasoning (Rest 1994) and we follow this practice throughout this paper. Various authors have proposed distinctions, but there does not seem to be one, generally accepted distinction. We would tend to use ‘ethical’ rather than ‘moral’ (unless in direct quotations) for the sake of internal consistency.

Ireland is a common law jurisdiction, so the results of this study are inherently relevant and applicable to other countries with similar systems, for example, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, etc.

The two other dilemmas in the short version of the DIT are the ‘Escaped Prisoner’ and the ‘Newspaper’ dilemmas. The ‘Escaped Prisoner’ scenario examines whether a man should pay for a past crime after living 8 years of a virtuous existence that contributed to the well-being of the local community. The ‘Newspaper’ dilemma examines freedom of speech as it relates to the press.

The two other dilemmas in the TPDIT are ‘Bar Talk’ and ‘Interpretation’. ‘Bar Talk’ examines whether a tax practitioner should report information he heard in a bar to the revenue authorities. ‘Interpretation’ examines mass marketing a tax planning product which goes against the spirit of the legislation.

On the link with risk management, see Doyle et al. (2009a).

A semi-state company is one in which the government has a controlling stake.

Under the Taxes Consolidation Act 1997, s. 1086, the Irish Revenue Commissioners are required to compile a list of the names, addresses and occupations of all ‘tax defaulters’. The list must be included in their annual report to the Minister for Finance and is published on a quarterly basis. The cases to be listed are: (a) all cases where a fine or penalty has been imposed by a court for a tax offence; and (b) all cases where a settlement has been reached with the Revenue for an amount over a specified sum of money and is paid in lieu of tax owed and penalties, unless a voluntary disclosure was made.

To check that these results were robust, the research hypotheses were retested using the GLM Repeated Measure model but also controlling for no degree level education (EDNODEGREE), below manager level in the firm (BELOWMANAGER), and years of tax experience, on the basis that these variables were significant at the 10 per cent level in regression analyses (Tables 7, 8). There was no change in the outcome with the only significantly different variable still being CONTEXT (P = 0.041). TPTYPE was still not significant (P = 0.936).

References

Abdolmohammadi, M. J., Read, W. J., & Scarbrough, D. (2003). Does selection-socialization help to explain accountants’ weak ethical reasoning? Journal of Business Ethics, 42(1), 71–81.

Ayres, F., Jackson, B., & Hite, P. (1989). The economic benefits of regulation: Evidence from professional tax preparers. The Accounting Review, 65(2), 300–312.

Bailey, C., Scott, I., & Thoma, S. (2010). Revitalizing accounting ethics research in the Neo-Kohlbergian framework: Putting the DIT into perspective. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 22(2), 1–26.

Barford, V., & Holt, G. (2012). Google, Amazon, Starbucks: The rise of “tax shaming”. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-20560359. Accessed 29 Dec 2012.

Bebeau, M., & Thoma, S. (2003). Guide for DIT-2, 3rd edn. Minnesota: Center for the Study of Ethical Development.

Bernardi, R. A., & Arnold, D. F. (1997). An examination of moral development within public accounting by gender, staff level and firm. Contemporary Accounting Research, 14(4), 653–668.

Bobek, D. D., & Radtke, R. R. (2007). An experimental investigation of tax professionals’ ethical environments. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 29(2), 63–84.

Bobek, D. D., Hageman, A. M., & Radtke, R. R. (2010). The ethical environment of tax professionals: Partner and non-partner perceptions and experiences. Journal of Business Ethics, 92(4), 637–654.

Burns, J. O., & Kiecker, P. (1995). Tax practitioner ethics: An empirical investigation of organizational consequences. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 17(2), 20–49.

Carnes, G. A., Harwood, G. B., & Sawyers, R. B. (1996). The determinants of tax professionals’ aggressiveness in ambiguous situations. Advances in Taxation, 8, 1–26.

Cooper, D. J., & Robson, K. (2006). Accounting, professions and regulation: Locating the sites of professionalization. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(4–5), 415–444.

Cruz, C. A., Shafer, W. E., & Strawser, J. R. (2000). A multidimensional analysis of tax practitioners’ ethical judgments. Journal of Business Ethics, 24(3), 223–244.

DeAngelo, L. E. (1981). Auditor size and audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 3(3), 183–199.

Doyle, E., Frecknall-Hughes, J., & Glaister, K. (2009a). Linking ethics and risk management in taxation: Evidence from an exploratory study in Ireland and the UK. Journal of Business Ethics, 86(2), 177–198.

Doyle, E., Frecknall-Hughes, J., & Summers, B. (2009b). Research methods in taxation ethics: Developing the defining issues test (DIT) for a tax specific scenario. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 35–52.

Doyle, E., Frecknall Hughes, J., & Summers, B. (2013). An empirical analysis of the ethical reasoning of tax practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(2), 325–339.

Dyreng, S., Hanlon, M., & Maydew, E. L. (2007). Long-run corporate tax avoidance. The Accounting Review, 83(1), 61–82.

Dyreng, S., Hanlon, M., & Maydew, E. L. (2010). The effects of executives on corporate tax avoidance. The Accounting Review, 85(4), 1163–1189.

Etherington, L., & Hill, N. (1998). Ethical development of CMAs: A focus on non-public accountants in the United States. Research on Accounting Ethics, 4, 225–245.

Etherington, L., & Schulting, L. (1995). Ethical development of accountants: The case of Canadian certified management accountants. Research on Accounting Ethics, 1, 235–251.

Eynon, G., Hill, N., & Stevens, K. (1997). Factors that influence the moral reasoning abilities of accountants: Implications for universities and the profession. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(12–13), 1297–1309.

Frecknall-Hughes, J. (2007). The validity of tax avoidance and tax planning: An examination of the evolution of legal opinion. Unpublished LLM dissertation, The University of Northumbria.

Frecknall-Hughes, J., & Moizer, P. (2004). Taxation and ethics. In M. Lamb, A. Lymer, J. Freedman, & S. James (Eds.), Taxation: An interdisciplinary approach to research (pp. 125–137). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gilligan, C. F. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Godar, S. H., O’Connor, P. J., & Taylor, V. A. (2005). Evaluating the ethics of inversion. Journal of Business Ethics, 61(1), 1–6.

Herman, T. (2004). IRS to issue rules on tax shelters; ethical guidelines target ‘opinion letters’ often used to justify questionable transactions. Wall Street Journal, D1.

Hume, E. C., Larkins, E. R., & Iyer, G. (1999). On compliance with ethical standards in tax return preparation. Journal of Business Ethics, 18(2), 229–238.

Jeffrey, C., & Weatherholt, N. (1996). Ethical development, professional commitment, and rule observance attitudes: A study of CPAs and corporate accountants. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 8, 8–31.

Johnston, D. C. (2004). Changes at KPMG after criticism of its tax shelters. New York Times, C1.

Jones, S., & Hiltebeitel, K. (1995). Organisational influence in a model of the moral decision process of accountants. Journal of Business Ethics, 14(6), 417–431.

King, N. (2004). Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organisational research (pp. 256–270). London: SAGE.

Kohlberg, L. (1973). Collected papers on moral development and moral education. Cambridge, MA: Laboratory of Human Development, Harvard University.

Krouse, S., & Baker, S. (2012). Osborne clamps down on tax abuse. Financial News. http://www.efinancialnews.com/story/2012-03-21/osborne-clamps-down-on-tax-abuse-in-budget. Accessed 29 Dec 2012.

Loeb, S. E. (1971). A survey of ethical behavior in the accounting profession. Journal of Accounting Research, 9(2), 287–306.

Marshall, R. L., Armstrong, R. W., & Smith, M. (1998). The ethical environment of tax practitioners: Western Australian evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(12), 1265–1279.

O’Dwyer, B. (2004). Qualitative data analysis: Exposing a process for transforming a ‘messy’ but ‘attractive’ nuisance. In C. Humphrey & B. Lee (Eds.), A real life guide to accounting research: A behind the scenes view of using qualitative research methods (pp. 389–405). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

OECD. (2008). Study into the role of tax intermediaries, 80. Cape Town, South Africa: Fourth OECD Forum on Tax Administration.

Pierce, B., & Sweeney, B. (2010). The relationship between demographic variables and ethical decision making of trainee accountants. International Journal of Auditing, 14(1), 79–99.

Ponemon, L. A. (1990). Ethical judgment in accounting: A cognitive-developmental perspective. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 1(2), 191–215.

Ponemon, L. A. (1992). Ethical reasoning and selection-socialization in accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(3/4), 239–258.

Ponemon, L. A., & Gabhart, D. R. L. (1993). Ethical reasoning in accounting and auditing. Vancouver, BC: Canada Research Foundation.

Pratt, J., & Beaulieu, P. (1992). Organizational culture in public accounting: Size, technology, rank, and functional area. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(7), 667–684.

Rest, J. (1979a). Development in judging moral issues. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Rest, J. (1979b). The impact of higher education on moral development. Minnesota: Minnesota Moral Research Projects, University of Minnesota.

Rest, J. (1986a). DIT: Manual for the defining issues test. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Centre for the Study of Ethical Development.

Rest, J. (1986b). Moral development. Advances in research and theory. New York: Praeger Publishers.

Rest, J. (1994). Background: Theory and research. In J. R. Rest & D. Narvaez (Eds.), Moral development in the professions (pp. 1–26). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Rest, J., & Narvaez, D. (1994). Moral development in the professions: Psychology and applied ethics (pp. 233). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.