Abstract

Professional integrity is a fundamental principle of the International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants Code of Ethics (IESBA, in Code of ethics for professional accountants, IFAC, New York; IESBA, Code of ethics for professional accountants, IFAC, New York, 2016). This does not apply directly to members of a particular professional body, but rather member organizations from around the globe are required to adopt a code no less stringent than the principles in the IESBA Code. Hence, all professional accountants are required to possess integrity as a core ethical principle. In the USA, certified public accountants must, in addition, also adhere to the principle of client advocacy in relation to their tax clients. Despite extensive prior literature on accounting ethics, firm culture, and ethical codes, no prior research has tested whether the communication of an Integrity ethical standard actually affects practitioners’ actual judgments and decisions. In this study, we use brief interventions to determine whether a prime of two ethical professional standards (Integrity; Advocacy) affects tax practitioners’ recommendations to their clients. One implication for professionalism in tax practice is our finding that a brief intervention of professional standards can directly impact on practitioners’ judgments. Most notably, a joint presentation of Advocacy and Integrity leads to contrasting results that depend on the order of the intervention. In sum, when the Integrity (Advocacy) standard was presented before the Advocacy (Integrity) standard, tax practitioners were significantly less (more) likely to choose a tax-favorable outcome. That is, the order of professional ethical standard intervention significantly affects tax practitioners’ judgments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Following high profile ethical lapses in the accounting profession over the last two decades, there have been questions raised about the integrity of the US accounting profession (Wyatt 2004), and how the global accounting profession is perceived by society (Carnegie and Napier 2010). Prior sociological and ethics research on professionals and accounting firms suggests that the organizational context of public accounting firms is increasingly important in shaping professional attitudes and behavioral norms, with the locus of professionalization (i.e., professional values and standards) becoming less of a focus (Bobek et al. 2015a, b; Brouard et al. 2017; Cooper and Robson 2006; Coram and Robinson 2017; Suddaby et al. 2009).

With a worldwide representation of 3 million accountants, 175 professional accountancy organizations in 130 countries/jurisdictions are members of the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). IFAC’s independent International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA) has published its own code of ethics, currently adopted by about 60% of member organizations (IESBA 2016; IFAC 2017, p. 21). The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) has its own Code of Professional Conduct which is the only ethics code in the USA applying to professional accountants at the national level (Jenkins et al. 2018; Spalding and Lawrie 2017; West 2018).

An extensive literature on ethical codes in accounting dates back to the 1990s (Beets and Killough 1990; Collins and Schulz 1995; David et al. 1994; Lindblom and Ruland 1997) and still remains topical with a thematic symposium on accounting professionalism (Gunz and Thorne 2017). Baudot et al. (2017), Desai and Roberts (2013), and Jenkins et al. (2018) all question the public vs. private interests of the AICPA and Spalding and Lawrie (2017) document the AICPA’s gradual shift from a ‘rules-based’ to a ‘principles-based’ ethics code. Aside from prior research focusing on the USA, West (2018) provides context to professional accounting ethics in a global setting, and highlights and analyses the role of integrity as the first of five fundamental principles of the IESBA Code. Integrity is seen as important because it enhances trust and reputation in the profession (Richardson 2018).

Professional associations’ codes of conduct apply to all members but tax practitioners in particular are cast in a unique role of serving the public interest with their accountability to both clients and tax agencies (amongst other stakeholders). As an example, in the UK, seven professional bodies jointly prepared and adopted a statement of professional conduct in relation to taxation, based on the IESBA Code, comprising the fundamental ethical principles and standards in taxation and guidance as to what is expected of members (e.g., Chartered Institute of Taxation 2018).

Despite this extensive prior international literature on accounting codes of ethics and the stated importance of integrity in accounting (e.g., ICAEW 2007), there are no published articles directly testing whether communicating an integrity ethical standard to accountants affects their professional judgments and client recommendations. Auditors and tax practitioners both adhere to codes of conduct acknowledging both integrity and advocacy, although the relative emphasis on different attributes of the code can vary by context (Bobek et al. 2015a).

In this study our objective is to integrate the prior literature on ethical codes of conduct discussed above with prior research focused on tax practitioners (Doyle et al. 2009, 2013, 2014; Frecknall-Hughes et al. 2017; Hume et al. 1999; Marshall et al. 1998) and to test experimentally the influence of a brief intervention on tax practitioners’ recommendations to their clients. We use a real estate tax case that while cast within the US tax code is common in many tax systems throughout the world. The case scenario requires the tax practitioner to choose between ordinary income and a capital gain, following a reminder of the standards for Integrity and/or Advocacy.

In answering our research question, we find even in a clear-cut case, that a brief intervention of an ethical standard can have an impact on tax practitioners’ decision making. In particular, order effects are observed for those exposed to both ethical standards. When the Integrity (Advocacy) standard was presented before the Advocacy (Integrity) standard, tax practitioners were significantly less (more) likely to choose a tax-favorable outcome. That is, the order of the presentation of the ethical standards significantly affected tax practitioners’ judgments, even though the total information provided was identical.

Our results have important implications for ethical standard-setters around the globe wanting to investigate the effect of communicating ethical standards on professional decision making. Given prior criticism of accountants’ role in tax avoidance, for example, they may also reassure tax agencies and assist accounting firm leaders and managers in actively setting and enforcing their organizational climate. Our study also has implications for accounting firms in general as they seek to balance commercial incentives with firm reputation (Coram and Robinson 2017) and improve the effectiveness of their staff training programs. The results also have implications for professional accounting associations and their individual members, who collectively are required to comply with ethical codes of conduct featuring integrity as a core principle. Such compliance may also contribute to a more positive sense of identity and well-being for individual professional accountants (Metzger 2011), together with an enhanced reputation for the accounting firm.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. The next section provides a framework of the accounting profession in general and professional accounting associations’ ethical codes of conduct together with a description of the tax practice environment, as well as developing our hypotheses. “Research Design and Method” and “Analysis and Results” outline our method and results respectively, with concluding remarks in “Conclusions”.

Background and Hypothesis Development

Context of Accounting Professionalism and Ethical Codes of Conduct

Richardson (2018, p. 128) notes that the traditional sociological view of the professions is that they were “a distinct class of occupations recognizable by their traits (e.g., use of codes of ethics, self-regulation, systems of education and credentialing) and their reliance on specialized and arcane knowledge”. At a broad conceptual level, Brouard et al. (2017) provide a framework of professional accountants’ identity formation which they suggest is influenced by society’s (governments, clients, general public, media) interplay via stereotypes/image with the accounting profession (comprising professional accounting associations, accounting firms and other employers). Brouard et al. (2017) conclude that professional accountants’ identity (and implicitly their professional attitudes and behaviors) are a complex phenomenon stemming from various audiences in society and the accounting profession.

From a global perspective, while the stated mission of IFAC is to “serve the public interest”, recurrent corporate scandals such as Enron, the global financial crisis, and revelations of corporate tax avoidance, have led the accounting profession, particularly in the USA, to come under criticism over large firms’ perceived lack of professionalism (Zeff 2003a, b). These criticisms are both in the market for audit services (Sikka 2009) and in the tax services market (Frecknall-Hughes and Kirchler 2015; Payne and Raiborn 2018). These criticisms have led to some soul-searching that is particularly related to ethics, with Wyatt (2004, p. 52) commenting that “[t]oo often, the accounting firms have acted at the direction of their clients in lobbying the FASB [Financial Accounting Standards Board] on specific technical issues and have not met the standards of professionalism that the public rightfully expects”. He opines that there needs to be firm-wide training in ethics, which must focus on underlying concepts (i.e., principles), rather than the “thou shalt nots” (i.e., do not break any rules).

To promote truthfulness in both financial reporting and by individual professional accountants, Bayou et al. (2011) argue that the accounting profession uses several mechanisms, including harsh penalties for violating the AICPA code of ethics, certification, a conservative culture of professionalism, and professional skepticism. Stung by these past scandals and criticisms, professional accounting associations worldwide, together with their umbrella organization (IFAC) and its independent ethics board (IESBA) have collectively responded by gradually revising their ethical codes of conduct.

The Principle of Integrity

The revisions to the codes of conduct have highlighted the importance of integrity as a critical ethical principle. Spalding and Lawrie (2017) note that the IESBA Code has adopted a principles-based (rather than rules-based) approach, which does not apply directly to members of a particular professional body, but rather the IFAC member bodies throughout the world are required to comply with a code no less stringent than the principles included in the IESBA Code of Ethics. The IESBA Code (2016, p. 15) prominently states: “The principle of integrity imposes an obligation on all members to be straightforward and honest in all professional and business relationships. Integrity also implies fair dealing and truthfulness”.

Similar to West’s (2018) portrayal of the importance of integrity as a fundamental principle of accounting professionalism, Carnegie and Napier (2010, p. 371) note “that the criticism of the accountants and auditors of the 1990s is that they are no longer persons of integrity” and they illustrate the tension (or balancing of competing objectives) between professional integrity and client advocacy by suggesting that the notion of “pleasing the client” has taken precedence over protecting the public interest, and if there are questions over accountants’ integrity, this will lead to wider ramifications for the professionalization of accounting (p. 372).

A further example of ethical code revision is provided by the AICPA. Under its revised Code of Professional Conduct (AICPA 2014) integrity is viewed as a core, element of character, fundamental to professional recognition, and required by all members (Spalding and Lawrie 2017). The 2014 version of the Code replaced an earlier version effective from 2010. In the 2014 Preface, Section 0.300.040 requires members to demonstrate the highest sense of integrity, and adds that integrity requires honest and candid reporting and that integrity does not permit deceit or subordination of principle (previously ET Section 54 in the 2010 Code). Another AICPA rule, Section 1.140 of the 2014 Code, (previously rule 102-6 in the 2010 version) implicitly acknowledges that accuracy can become subjective in the presence of ambiguous technical guidance.Footnote 1

An important area of accounting for professional accountants is taxation, although only recently have steps been made toward a general theory of tax practice (Frecknall-Hughes and Kirchler 2015). The tax services market is fragmented, but common elements include the provision of tax planning services and compliance work, together with other functions such as representing taxpayers in disputes. Frecknall-Hughes and Kirchler (2015, p. 291) note that tax practitioners may include professional accountants, as well as lawyers and other individuals that may operate a public practice, work for a tax agency, or in-house in a corporate tax function. This study focuses on CPAs, although we acknowledge that these other groups of tax practitioners may respond differently to primes of integrity and/or advocacy.

Given the potential tensions between client service and serving the public interest as a professional accountant who demonstrates professional integrity, it is not surprising that researchers have long studied the ethical behavior of tax professionals (Marshall et al. 1998; Hume et al. 1999). Doyle et al. (2013, 2014) experimentally test an adapted Defining Issues Test instrument specifically designed for tax practitioners, and find results supporting a socialization effect in client-driven firms, which confirms other sociological research on accounting firms’ organizational climate in both audit and tax (Bobek et al. 2015a, b; Frecknall-Hughes et al. 2017).

Figure 1 summarizes our research focus and design. It uses the Libby Box technique (Libby 1981) for studies using the approach of an experiment. The top two boxes indicate the conceptual focus, examining the relation between professional ethical codes and tax decision making. The bottom two boxes display how the experiment addresses this question, using primes for advocacy and integrity as the independent variables, and a decision on a real estate case as the dependent variable.

At the level of individual tax accountants, Roberts (1998) reviews 52 studies and provides a framework showing that the judgments and decisions of tax practitioners are influenced by individual cognitive and affective psychological factors (e.g., knowledge, ethical attitude), the tax environment (including various client-related incentives and task factors such as complexity of the tax law), and cognitive processing factors. The next sub-section emphasizes US research focusing on individual tax practitioners published since Roberts’ (1998) review, concentrating on client advocacy research.

Tax Practitioners’ Client Recommendations and Client Advocacy in the US

In the US tax environment, Kadous and Magro (2001, p. 453) highlight the requirement of tax professionals to “be advocates for all client positions that are within statutory bounds … [and] objectively evaluate all relevant facts and tax authorities when preparing advice”. Indeed, the AICPA Code of Conduct continues to acknowledge the need for taxpayer advocacy. In addition, tax practitioners’ practicing in the USA are also regulated by various code sections of the Internal Revenue Code, although CPAs are exempt from IRS return preparer rules, introduced after a review (IRS 2009) as they are considered to adhere to the professional standards contained in the AICPA’s own Code of Conduct.

Prior research has compared professional role and decision context (i.e., audit vs. tax) in relation to client advocacy, with mixed results as to the differences between the two roles and contexts. For example, Pinsker et al. (2009) find that professional accountants’ attitudes are moderated by the requirements of the specific decision environment, and specifically, that tax practitioners’ judgments closely mirror their attitudes, whereas this link is significantly weaker in an audit decision environment. They find that practitioners who have worked in both tax and audit exhibit more neutral attitudes than those who have worked only in tax, or only in audit. Bobek et al. (2015a) also demonstrate the importance of decision context finding that auditors are less likely than tax professionals to recommend conceding to a client, although this was found only for male participants.

In a qualitative study of in-house tax practitioners at multi-national firms in Silicon Valley, Mulligan and Oats (2016) note that while their participants work largely in the shadows in their own organizations, they are able to influence significantly and shape tax law and practices, both in their organizational fields and in the wider economic and political environments. Interestingly, one participant highlighted a tension in his/her professional role of acting in the interests of the firm but still having a professional obligation to maintaining the overall integrity of the tax system: “I want to develop a good relationship with the IRS so I will never do anything which would jeopardize because it’s not my money right. I want to do the right stuff for the company and for the government … [I think of myself as] like a semi government agent” (Mulligan and Oats 2016, p. 72).

Within a personal tax setting, Stephenson (2007) finds that tax practitioners equate client advocacy with aggressive tax positions (and saving money for their clients), while taxpayers’ reasons to engage a tax preparer also include the objectives of increased tax return accuracy and reducing the probability of tax audit (Fleischman and Stephenson 2012). Bobek et al. (2010) review over 20 prior studies on client advocacy in a tax setting and provide evidence that client characteristics influence practitioners’ advisory attitudes, and they suggest that advocacy may be context-specific, with client-specific advocacy influencing multiple steps in practitioners’ judgment and decision-making processes. They conclude that tax practitioners may find it difficult to separate their client advocate role from their objective evidence evaluator role, which potentially affects tax advice recommendations.

Several studies have documented that individuals’ attitude toward client advocacy correlates with preferences for client-favorable outcomes (e.g., Davis and Mason 2003; Johnson 1993; Levy 1996), although Barrick et al. (2004) did not. When advocacy has been tested by manipulating client preference, research tends to show a positive association as practitioners strive to help their clients, provided the hypothetical client is not too risk-seeking or too risk-averse (Cuccia et al. 1995; Hackenbrack and Nelson 1996; Kadous et al. 2008).

In the first cross-cultural research in this area, Spilker et al. (2016) study client advocacy and reporting recommendations using both US and offshore Indian tax practitioners. Strong client advocacy attitudes are found for experienced US practitioners, relative to inexperienced US and all Indian tax practitioners. Strong advocacy attitudes are positively associated with US practitioners making more client-favorable recommendations, but this was not found for the Indian participants.

Hypothesis Development

We investigate the effect of communicating professional accounting ethical standards on tax practitioners’ client recommendations. In particular, by presenting a prime for professional integrity, we expect participants to make more deliberative judgments, and to consider ethical issues in their judgments and reporting recommendation. Conversely, with a prime of client advocacy, we expect participants to focus on client interests (Collins and Schulz 1995).

Of course, participants may already have a predilection towards either the public interest or a client interest (Lindblom and Ruland 1997) without the brief intervention. In this regard, Fogarty and Jones (2014) interviewed tax practitioners about the impact of professional standards. Their interviewees indicated they were aware of the ethical standards, stating that professional standards are “in the back of our mind all the time”, although they are rarely read (p. 301). This result implies that practitioners already have their own individual mindset, such that any intervention would not provide enough additional information sufficient to change their judgments. If true, this biases against finding any significant effect (of communicating an ethical standard) in our results. Our first hypothesis, described below, tests whether a brief intervention has any impact on practitioners’ client recommendations and their assessment of court support if the issue was litigated. As well, the consequent analysis establishes a baseline for our participants in the absence of any primes.

H1

A prime of a professional ethical standard will influence tax practitioners’ client recommendations.

Our second hypothesis tests the prediction that those in the group primed by reminders for integrity will make more conservative judgments than those in the group primed by a reminder for client advocacy. This expectation is formed on the premise that a reminder for a particular prime will make that aspect of a practitioner’s obligation more salient and therefore impact recommendations to the client. To the extent that a practitioner’s attitudes are already firmly established, we may find no effect at all, though not one opposed to the presented primes. As a result, our second hypothesis, unlike our first, contains a directional prediction:

H2

Tax practitioners primed with an Integrity ethical standard will make more conservative client recommendations than those primed with an Advocacy ethical standard.

Effect of Combined Presentation of Professional Standards

Bonner (2008) reviews order effects and concludes that mixed data with step-by-step processing (disaggregated data with paired subsequent judgments) generally result in a recency effect, whereas, primacy effects are more likely with simultaneous processing (aggregated data prior to any subsequent judgments). In the context of professional standard-setting, Asay et al. (2017) explain that contrast effects can occur if the interpretation of the target standard is influenced away from the treatment indicated by the out-of-regime standard. Several accounting studies have documented contrast effects (e.g., Bhattacharjee et al. 2007; Maletta and Zhang 2012), with Asay et al. (2017) noting that psychology research suggests that contrast effects become more likely as two objects become more dissimilar.

The two primes in our study are dissimilar in that professional integrity reflects a public interest, whereas client advocacy, by design, reflects a client interest. We hypothesize that a contrast effect will occur, but that any order effect will be contingent on whatever standard is primed first. This leads to our third hypothesis:

H3

When tax practitioners are primed with both ethical standards, they will make more (less) conservative client recommendations when the Integrity (Advocacy) is primed first, relative to when Advocacy (Integrity) is primed first.

Research Design and Method

Participants

Our participants are 132 professional accountants who work primarily in the tax area. Two large international firms agreed to help with the distribution and completion of the questionnaires. In addition, questionnaires were distributed at a tax CPE session provided by the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA). This allowed us to test our research question over a wide range of practitioners in regard to tax experience, firm size, job position, and geographical location. The international firms distributed the questionnaires to tax offices in different regions across the country, while the NASBA session was held in Chicago and New Orleans. Two versions of the questionnaire were created—one was in paper form (used at NASBA and by one of the international firms) and the other was converted to an online platform using SurveyMonkey® (at the other international firm). The responses do not significantly vary by method of collection, nor between the in-house participants from the large, international firms and the participants attending the NASBA tax session.

Design

We use a 1 × 5 between-subjects design to test our hypotheses, and participants were randomly assigned to one of the five experimental conditions varying whether, and which, primes for advocacy and integrity were presented (see Fig. 1). One of the five conditions is a control group. The control group did not receive any excerpt of the AICPA Code. As a baseline condition, they were simply asked to respond to the real estate tax case and questions described later in this section.

Two of the five groups received a brief Integrity intervention, or an Advocacy intervention (refer to Appendix 1). To operationalize the two treatments, each participant was asked to read an excerpt of the AICPA (2010) Code before turning to the next page to read and consider the real estate tax case. These two groups read only one isolated standard: Advocacy (as found in Section 102.07 in the Code of Conduct) or Integrity (as found in Sections 54.02 and 54.04 of the Code).

The remaining two groups were primed with both standards, but the order or presentation was altered in order to test for a primacy effect. The similarly-sized, primed conditions that were extracted directly from the Code were as follows:

Integrity requires a member to be, among other things, honest, and candid. Service and the public trust should not be subordinated to personal gain and advantage. Integrity can accommodate the inadvertent error and the honest difference of opinion; it cannot accommodate deceit or subordination of principle … Integrity also requires a member to observe the principles of objectivity and independence of due care.

[Integrity]

A member or a member’s firm may be requested by a client … (1) To perform tax or consulting services engagements that involve acting as an advocate for the client. (2) To act as an advocate in support of the client’s position on accounting or financial reporting issues, either within the firm or outside the firm with standard-setters, regulators, or others.

[Advocacy]

Case Scenario and Variables

We use an unambiguous real estate case in which outside experts have agreed that a conservative treatment (classifying the income as ordinary) is more accurate than an aggressive one (classifying the gain as capital). Participants were asked to make a recommendation on whether a client would be treated as a dealer or investor with regard to a sale of real estate lots. Given that the sale had generated a profit, the client’s preference would be for the latter, i.e., that the property would be considered a capital asset under the US Internal Revenue Code (I.R.C. § 1221(1)). If the client was considered a dealer, then the income from the sale would be classified as ordinary and subject to a tax rate of approximately 40%. However, classifying the client as an investor would mean that the sale would comprise a long-term capital gain and be subject to a lower tax rate of only 20%.

The treatment provided a reminder of the relevant section from the regulations, a description of the fact pattern, and then requested both a recommendation regarding the client’s tax treatment and the likelihood that courts would conclude the client was an investor. Participants were then asked to provide more information, including their assessment of the quantity and quality of facts provided, interpretation of standards from the Code, and a variety of background questions regarding their tax experience and general attitude toward client advocacy (refer to Appendix 2).

Participants also responded to a question asking with which, if any, of the standards they had been presented just before reading the case. Three individuals answered this question incorrectly. The ensuing analysis incorporates the responses of the 129 individuals who correctly noted the materials they had been given, although results are statistically unchanged when all responses are included.

The context for the case study is shown in Appendix 2, and it was adopted from Cloyd and Spilker (1999). The case has continued to find use in tax research, most recently by Spilker et al. (2016). To determine whether a search bias would persist when the facts do not support a client-favorable outcome, Cloyd and Spilker consulted tax experts who helped revise a previously ambiguous real estate case to a clear-cut client-unfavorable case. The experts who were consulted (one partner, one principal, and two senior tax managers, all with extensive real estate experience) agreed that the likelihood of a successful outcome if litigated was only 10–20% (mean of 14%). The four experts reported a strong preference for dealer status, with a mean of 1.75 on a scale of 1 (strongly recommend dealer)–7 (strongly recommend investor). Even so, Cloyd and Spilker (1999) found that 46% of their tax practitioner sample recommended investor status—i.e., contrary to what the experts found. Moreover, their respondents indicated an average 48% likelihood that the courts would support investor status—much higher than the 14% likelihood reported by the experts.

Consistent with their research, we chose not to use a more ambiguous case, because client-favorable responses on an ambiguous case would not necessarily be incorrect or aggressive. The expected response to a deliberately pro-dealer case should be a conservative approach that leans toward dealer status, even though this is unfavorable to the client. According to the experts, if a practitioner recommended investor status (which would be preferred by the client), this would in fact be erroneous and not supported by the case facts, IRS practice, and case law. Yet, if found in a study’s results, this would be consistent with Klayman (1995) who explained confirmation bias in a psychology context, as the extent to which a confirming tendency exceeds an appropriate level.

The primary dependent variable measured each participant’s intended recommendation regarding dealer or investor status. It should also be noted that the dependent variable represents an intended behavior.

Analysis and Results

Descriptive Data

A total of 129 practitioners completed the questionnaires on a voluntary and anonymous basis. Demographics are shown in Table 1. Most participants (60.4%) were 40 or above, while 17.1% were in their 30s, and 9.9% were between 20 and 24 years old; 66.7% were male. Only 26.3% had less than 2 years of tax experience. The average percent of time for chargeable tax work was 70.2%, and 9.4% of the chargeable time involved real estate issues. Most respondents had significant work experience as 22.1% were managers and 52.9% were at the partner or equivalent level. Cloyd and Spilker (1999) did not report their respondents’ position level, but their reported average experience was 22.9 months, suggesting a less experienced group of tax professionals participated in their study. Another difference in their respondents compared with ours is the level of education. Those with bachelor degrees were 37% in the Cloyd and Spilker (1999) study and 57% in the current study; 24% of the Cloyd and Spilker (1999) participants had masters degrees vs. 29% in the present study; lastly, 39% had law degrees in the former study, with only 7% in our study.

Advocacy Scale and Background Questions

To capture internal beliefs about client advocacy, our participants completed the Mason and Levy (2001) advocacy scale as condensed by Pinsker et al. (2009). The scale includes five questions with a high reliability score: 0.85 Cronbach’s alpha in Pinsker et al. (2009) and 0.88 in the current study. Respective means on the 7-point scale in the Pinsker et al. (2009) study was 4.61 for professionals with mostly tax experience but some audit or other accounting experience and 4.09 in our study using practitioners whose dominant work area is tax, as shown in Table 2. Given that 7 represents strong agreement with client-favorable judgments, participants in the current study were non-committal and hovered closely to the midpoint score of 4.

Although studies have documented the significant effects of advocacy, statistical correlations are not large. For example, the significant correlation between advocacy attitude and recommended tax position in Johnson (1993) was 0.17, 0.13 in Pinsker et al. (2009), and insignificant in Barrick et al. (2004). Bobek et al. (2010) note that most prior research did not use a scale to measure individual advocacy attitude. Cloyd and Spilker (1999) induced a treatment effect for advocacy by describing a tax position that would help the client minimize tax. In Ayres et al. (1989), the underlying premise of the decision variable was to capture practitioners’ propensity to prefer decisions that are favorable for the client (i.e., reduce taxable income). This is consistent with research finding that most practitioners assume their clients prefer tax saving strategies, even when not explicitly requested (Christensen 1992; Stephenson 2007), and the tax literature is replete with studies acknowledging practitioners’ tendency to favor pro-client judgments (Ayres et al. 1989; Christensen 1992; Cloyd and Spilker 1999; Cloyd et al. 2012; Cuccia et al. 1995; Johnson 1993; Stephenson 2007).

Although a pro-client tendency is commonly documented, Pinsker et al. (2009) concluded that the advocacy scale captures a general tendency toward advocacy, but that practitioners’ propensity to be an advocate is dependent on the specific tax issue being considered. To control for advocacy attitude in general, we measured advocacy scale in the present study to ensure random assignments to treatment groups were effective, and we found no significant difference between our groups on the advocacy scale. Moreover, the advocacy scale for general attitude did not significantly correlate with any of our outcome variables. Importantly, the advocacy scale was not presented to our participants until after they had already made decisions and noted these in the instrument.

Regarding familiarity with the current standards, participants who received a brief presentation of the professional standards prior to reading the hypothetical case were asked to respond on a scale of 1–7 (with 7 = Very Familiar) to indicate their familiarity with the Code, and then with the specific standard that was presented, either Advocacy, Integrity, or both (Appendix 1). Overall, 66.3% indicated they were familiar with the AICPA Code of Conduct (scores from 5 to 7) with a mean of 4.8 (SD = 1.4). For the Advocacy standard, 44.7% were familiar with a mean of 4.3 (SD = 1.6). For the Integrity principle, 72.4% were familiar with a mean of 5.0 (SD = 1.4). These responses as well as the advocacy scale and the demographic variables noted above did not significantly correlate with any of the dependent variables.

After completing the case-related questions and the advocacy scale, all participants were asked a variety of background questions regarding demographics (as discussed earlier), experience on dealer-investor issues, and about their interpretation of the Advocacy and Integrity ethical standards. When asked whether the Advocacy standard results in a more client-favorable interpretation of the standards, on a scale of 1–7, in which 7 represents “much more favorable”, the mean was 4.5 (SD = 1.0). Only 7.1% indicated it was unfavorable (scores of 1–3), and 50.9% indicated it was favorable for the taxpayer (scores of 5–7), as shown in Table 2. Taxpayer favorability on the Integrity standard had a mean of 4.2 (SD = 0.8) with 14.3% indicating it was unfavorable, 27.7% indicating it was favorable, leaving 58.0% with a non-committal score of 4. To the extent that wording of the standards may be unclear to some, the general concept toward potential client bias seemed to be understood. Interestingly, even though our findings show a treatment effect on the outcome variables related to the presented ethical standards, participants’ interpretation of these standards did not vary between any of the treatment groups. Thus, as demonstrated later, participants’ decision making on the outcome variables was affected by the standards presented, even though they did not differ in their stated interpretation of the standards.

Dependent Variables

We measure the outcome variables with our primary dependent variable, behavioral intent to recommend investor status (RECO), as well as its principal supporting variable, perceived probability that courts would view the client as an investor (COURT). For RECO, participants could provide a response of − 3 to + 3, where − 3 (+ 3) indicates a strong recommendation for the dealer (investor) position. The mean response was − 1.16 (SD = 1.77). For COURT, participants could provide a percentage response ranging from 0 to 100; the mean response was 37.65 (SD = 27.98).

The first hypothesis tests whether a brief intervention, in the form of primes for professional ethical standards, influences the decisions of tax professionals. An overall ANOVA for all groups indicates an effect of treatment, as shown in Table 3. In this test, we examine the primary dependent variable, RECO, indicating the practitioner’s recommendation for Jim Hunt to take on his tax return. Planned comparisons are discussed and shown in subsequent tables, but the overall effect is significant (F4,124 = 2.778; p = 0.03). We also find a marginally significant effect for COURT, indicating the perceived probability that if litigated, courts would find Jim Hunt to be an investor (F4,123 = 2.114; p = 0.083).

Advocacy vs. Integrity

Table 4 presents a test of the second hypothesis, comparing the results of those primed with Integrity to those primed with Advocacy. We find no statistical difference between these two groups. For RECO, participants presented with the Integrity standard gave a mean response of − 1.19 (SD = 1.67). Participants presented with the Advocacy standard gave a mean response of − 0.96 (SD = 1.84). Both groups showed a tendency to consider Jim Hunt a dealer. An independent-samples t test reveals the Advocacy and Integrity groups to be statistically similar (t53 = 0.467; p = 0.321Footnote 2). For COURT, participants presented with the Integrity standard gave a mean response of 37.67% (SD = 28.29). Participants presented with the Advocacy standard gave a mean response of 39.09% (SD = 27.45). Again, both groups showed a tendency to consider Jim Hunt a dealer. An independent-samples t test reveals the two groups to be statistically similar (t53 = 0.189; p = 0.426).

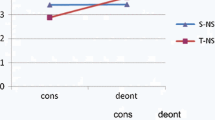

Order Effects of Combined Standards

Table 5 presents a test of the third hypothesis, comparing the results of those primed with the Advocacy and Integrity standards (with Advocacy presented first) with those primed with the Advocacy and Integrity standards (with Integrity presented first). We find a significant statistical difference between these two groups. For RECO, participants presented with the Integrity standard first gave a mean response of − 1.60 (SD = 1.29). Participants presented with the Advocacy standard first gave a mean response of − 0.29 (SD = 2.22) demonstrating ambiguity on an expert-defined unambiguous case. Both groups showed a tendency to consider Jim Hunt a dealer. However, an independent-samples t test reveals the two groups to be statistically different (t47 = 2.538; p = 0.008). For COURT, participants presented with the Integrity standard first gave a mean response of 26.46% (SD = 18.96). Participants presented with the Advocacy standard first gave a mean response of 49.25% (SD = 31.16). Again, both groups showed a tendency to consider Jim Hunt a dealer, yet when Advocacy was presented first, nearly half believed the ‘unfavorable’ case would be favorable in a court of law. An independent-samples t test reveals the two groups to be statistically different (t46 = 3.062; p = 0.002). These results are consistent with Hypothesis 3 and indicate that when combined standards for Integrity and Advocacy are presented, the order of presentation heightens the effect of the initial prime. This is in spite of the fact that each group of participants saw the same objectively equivalent total amount of information.

Supplemental Analysis

Advocacy Prime Versus Integrity Prime

Bonner’s (2008) review of order effects considers not only the contrast-inertia effect of aggregated and disaggregated data itself, but the perspective of the decision maker. She asserts that order effects occur when a priori beliefs are non-committal, because the presented information will be perceived as credible. Hence, she concludes that order effects are more likely when priors are around 50%, representing a level of uncertainty about which directional outcome is the appropriate choice. In other words, order effects are most likely when dealing with ambiguous or unclear issues as the subjects have yet to draw any strong conclusion about the outcome. Given that the current study used a case that was low in ambiguity, the contrasting results from the order manipulation are especially noteworthy and warrant further examination.

A corollary to our hypotheses is that those primed with the Integrity standard first, whether by itself or preceding Advocacy, would respond more conservatively than those primed with Advocacy first, whether by itself or preceding Integrity. This is supported for both outcome variables, RECO and COURT. For RECO, those initially primed with the Integrity standard provided a mean response of − 1.38 (SD = 1.50), while those initially primed with the Advocacy standard provided a mean response of − 0.65 (SD = 2.03). An independent-samples t test reveals the two groups to be statistically different (t102 = 2.090; p = 0.020). For COURT, those initially primed with the Integrity standard provided a mean response of 32.39% (SD = 24.77), while whose primed initially primed with the Advocacy standard provided a mean response of 43.78% (SD = 29.37). An independent-samples t test reveals the two groups to be statistically different (t101 = 2.125; p = 0.018).

In testing the above corollary, the means of all four groups are in predicted directions; however, the statistical significances are driven by the stark contrast between the groups presented with both standards in opposite order. The expectation was that participants seeing both primes would be especially impacted by the first prime seen, and therefore their view of that statement’s favorability to the client should be correlated with their final judgments. As mentioned previously, participants were randomly assigned to separate groups, so, unsurprisingly, there is no statistical difference in advocacy attitudes between groups. However, for the participants presented with an Advocacy standard followed by an Integrity standard, their agreement that the Advocacy standard allows for a more client-favorable interpretation is correlated with both RECO (r = 0.395; p = 0.031) and COURT (r = 0.355; p = 0.049). Their interpretation of the Integrity standard, though, has no statistical correlation with their final judgments. Conversely, for participants presented with the Integrity standard followed by the Advocacy standard, their agreement that the Integrity standard allows for a more client-favorable interpretation is correlated with both RECO (r = 0.575; p = 0.006) and COURT (r = 0.394; p = 0.053). Their interpretation of the Advocacy standard, though, has no statistical correlation with their final judgments. Whether these correlations drove the actual judgments or, instead, were impacted on simultaneously with the judgments, there appears to be an emphasis on the first primed intervention of an ethical standard.

The Control Group

It is interesting to note that those in the control group provided largely conservative responses, with means for RECO and COURT of − 1.76 (SD = 1.48) and 35.64% (SD = 29.77), respectively. The expectation that the Advocacy standard would generate more aggressive responses is true not only when comparing to those in the Integrity group, but also when comparing to the control group (not tabulated). However, the responses of those initially primed with Integrity are not significantly different from those in the control group. Establishing a baseline response for those without a prime is informative, but from an experimental design standpoint, it can be difficult to make far-reaching conclusions based on something’s absence, because it is unclear which other factors may have taken precedence in its place. Fogarty and Jones (2014) assert that standards are always in practitioners’ minds, and that firm culture plays an important role as well, but as noted earlier, there are other factors that may come into play (Brouard et al. 2017; Roberts 1998). In addition, practitioners may rely on past precedents or their own previously-formed norms. These factors may be more significant when primes are absent. In other words, those in the control group may have already possessed integrity; or, their responses may have been due to completely independent causes.

Results for the control group are consistent with the tax experts in Cloyd and Spilker (1999). One could question whether priming ethical standards is at all useful given the conservative, client-unfavorable responses of the control group. Such a conjecture, however, is problematic, because this study used a client-unfavorable case instead of an ambiguous one. Finding a significant and novel result on this case demonstrates the potential impact of primes for ethical standards. If the same tax issue with more ambiguous facts were examined, the theories would clearly posit significant effects for the single and jointly presented standards, as well as an order effect for the jointly presented standards. The implications of such results, however, would be questionable because the outcomes could not be classified as erroneous if the cases were indeed ambiguous. By using an unambiguous case, we demonstrate that even in a client-unfavorable case with a group of rather experienced tax practitioners, professional ethics standards’ interventions can influence practitioners’ judgments.

Conclusions

Prior ethics research has noted that decision context is important to tax practitioner judgment, and this has been specifically noted when comparing the fields of audit and tax (Pinsker et al. 2009; Bobek et al. 2015a, b). However, a large body of prior ethics research has not directly examined the effect of communicating ethical standards under the IESBA (2016) or AICPA (2010, 2014) codes of conduct, leaving this an open question for study.

We used a previously-tested tax case for classifying the sale of real estate lots as either capital gains, in which the taxpayer is considered an investor, or as ordinary income, in which the taxpayer is considered a dealer (Spilker et al. 2016). Professional accountants focusing in the area of tax participated in our study. We investigate the impact of Integrity and Advocacy interventions, both separately and in combination, on the judgments of tax practitioners. The participants of our study were asked to read the fact pattern and make a recommendation to the client as to the classification of the sale. They were then asked to assess the likelihood that a claim for investor status would withstand court scrutiny.

Our study is the first to provide evidence that communicating professional ethical standards does have an effect on practitioners’ decisions. Most notably, we observe order effects for those exposed to both primes. Participants seeing Integrity first, followed by Advocacy, were more likely to consider the taxpayer a dealer than those seeing Advocacy first, followed by Integrity. These responses differed even though the total amount of information presented to the participants was identical in each condition. Note that the raw number for the response to the Advocacy standard is larger than that for the Integrity standard. It is possible that the Advocacy condition would have yielded a more client-favorable response if the size of the sample was larger. The sample size reveals the most pronounced issues, adding support to the applicability of our findings for order effects in practice.

The observed effects occur even though the case is not neutral, but possesses a fact pattern biased toward a dealer classification. Cloyd and Spilker (1999) argue that results on a truly ambiguous case cannot be interpreted as “biased” if the true outcome is unknown. Using a case with an expert-agreed consensus reduces the likelihood that any deviation from the expected answer is caused by the uncertainty of the case itself. Thus, any resulting outcome is more likely to be explained by our hypothesized effects. Interestingly, a baseline condition using no primes resulted in the most conservative responses: one interpretation of this result is that professional accountants automatically bring a certain ethical mindset with them, though their responses may have been due to factors arising from their firms or previously-formed norms.

Any experimental study using abbreviated primes has the risk of being a weak manipulation. The theory of comparative analysis, however, purports to increase the attentiveness given to a prime when the prime is presented along with a relevant, but distinct pairing. Given that a comparative approach has been an effective method of increasing salience in psychology, it is appropriate to consider its use in the wording and order of professional standards. The implication for standard-setters around the world is that careful consideration should be given to presentation. If one standard should take precedence over a second, counterbalancing standard, the IESBA and IFAC’s member organizations around the world may wish to present them to their professional members jointly with the more relevant standard first. In addition, we chose to use wording with which the practitioners may have already been familiar.

Apart from professional accounting associations, this study has implications for accounting firms in terms of their staff training programs. Reinforcing the need for integrity while balancing client advocacy objectives as part of training and development programs, may reduce the firm risk from exposure to tax positions that could be targeted by government tax agencies. In addition, dealing with the tension from counterbalancing standards will reduce the likelihood of individual professional accountants breaking their association’s ethical standards which could lead to damaging reputational effects, both at a personal and firm level.

The usual limitations associated with an experimental research method apply to this study. While generalizability can be a concern, this is mitigated by having participants from a range of firms with a broad distribution of experience. In addition, our study is limited in that we only established priors for two ethical standards, being integrity and client advocacy. We did not test other ethical standards from IESBA (2016) or AICPA (2014) such as objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality etc. Finally, we used one single ‘dealer’ vs. ‘investor’ real estate tax case and it is possible that another case might lead to different results, although the case has been developed and used by several other researchers (e.g., Spilker et al. 2016).

Future research should continue to focus on the effect of communicating all of the ethical standards, not just those for integrity and advocacy, issued by the worldwide member associations of IFAC on the ethical judgments and decisions of their professional members. Prior research and our findings suggests that decision context can matter, so future work should not be restricted to just one area of accounting but should cover external audit, tax, consulting etc. Finally, standard-setters should consider the most efficacious manner in which their ethical standards can be communicated to professional accountants.

Notes

The Section’s first paragraph states “An advocacy threat to compliance with the “Integrity and Objectivity Rule” [1.100.001] may exist when a member or the member’s firm is engaged to perform non-attest services, such as tax and consulting services, that involve acting as an advocate for the client or to support a client’s position on accounting or financial reporting issues either within the firm or outside the firm with standard-setters, regulators, or others”. Also, paragraph 3 states: “Some professional services involving client advocacy may stretch the bounds of performance standards, go beyond sound and reasonable professional practice, or compromise credibility, thereby creating threats to the member’s compliance with the rules and damaging the reputation of the member and the member’s firm. If such circumstances exist, the member and member’s firm should determine whether it is appropriate to perform the professional service”.

One-tailed (two-tailed) tests are conducted for directional (non-directional) predictions. In addition, we supplemented our analysis with randomization techniques described in Good (2005), in which resampling methods are used to construct random comparison distributions from the observed data. This process yielded no changes in our statistical inferences.

References

AICPA. (2010). AICPA code of professional conduct. New York: AICPA.

AICPA. (2014). AICPA code of professional conduct. New York: AICPA.

Asay, S., Brown, T., Nelson, M., & Wilks, J. (2017). The effects of out-of-regime guidance on auditor judgments about appropriate applications of accounting standards. Contemporary Accounting Research, 34(2), 1026–1047.

Ayres, F., Jackson, B., & Hite, P. (1989). The economic benefits of regulation: Evidence from professional tax preparers. The Accounting Review, 64(2), 300–312.

Barrick, J., Cloyd, B., & Spilker, B. (2004). The influence of biased tax memoranda on supervisors’ initial judgments in the review process. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 26(1), 1–21.

Baudot, L., Roberts, R. W., & Wallace, D. M. (2017). An examination of the U.S. public accounting profession’s public interest discourse and actions in federal policy making. Journal of Business Ethics, 142(2), 203–220.

Bayou, M., Reinstein, A., & Williams, P. (2011). To tell the truth: A discussion of issues concerning truth and ethics in accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 36(2), 109–124.

Beets, S. D., & Killough, L. N. (1990). The effectiveness of a complaint-based ethics enforcement system: Evidence from the accounting profession. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(2), 115–126.

Bhattacharjee, S., Maletta, M., & Moreno, K. (2007). The cascading of contrast effects on auditors’ judgments in multiple client audit environments. The Accounting Review, 82(5), 1097–1117.

Bobek, D., Hageman, A., & Hatfield, R. (2010). The role of client advocacy in the development of tax professionals’ advice. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 32(1), 25–51.

Bobek, D., Hageman, A., & Radtke, R. (2015a). The effects of professional role, decision context, and gender on the ethical decision making of public accounting professionals. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 27(1), 55–78.

Bobek, D., Hageman, A., & Radtke, R. (2015b). The influence of roles and organizational fit on accounting professionals’ perceptions of their firms’ ethical environment. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(1), 125–141.

Bonner, S. (2008). Judgment and decision making in accounting. Upper Saddle River: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Brouard, F., Bujaki, M., Durocher, S., & Neilson, L. C. (2017). Professional accountants’ identity formation: An integrative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 142(2), 225–238.

Carnegie, G., & Napier, C. (2010). Traditional accountants and business professionals: Portraying the accounting profession after Enron. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(3), 360–376.

Chartered Institute of Taxation. (2018). Professional conduct in relation to taxation. London: CIOT.

Christensen, A. (1992). Evaluation of tax services: A client and preparer perspective. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 14(2), 60–87.

Cloyd, B., & Spilker, B. (1999). The influence of client preferences on tax professionals’ search for judicial precedents, subsequent judgments and recommendations. The Accounting Review, 74(3), 299–322.

Cloyd, B., Spilker, B., & Wood, D. (2012). The effects of supervisory advice on tax professionals’ information search behaviors. Advances in Taxation, 20, 135–158.

Collins, A., & Schulz, N. (1995). A critical examination of the AICPA code of professional conduct. Journal of Business Ethics, 14(1), 31–41.

Cooper, D. J., & Robson, K. (2006). Accounting, professions and regulation: Locating the sites of professionalization. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(4–5), 415–444.

Coram, P., & Robinson, M. (2017). Professionalism and performance incentives in accounting firms. Accounting Horizons, 31(1), 103–123.

Cuccia, A., Hackenbrack, K., & Nelson, M. (1995). The ability of professional standards to mitigate aggressive reporting. The Accounting Review, 70(2), 227–248.

David, J. M., Kantor, J., & Greenberg, I. (1994). Possible ethical issues and their impact on the firm: Perceptions held by public accountants. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(12), 919–937.

Davis, J., & Mason, D. (2003). Similarity and precedent in tax authority judgment. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 25(1), 53–71.

Desai, R., & Roberts, R. (2013). Deficiencies in the code of conduct: The AICPA rhetoric surrounding the tax return preparation outsourcing disclosure rules. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(3), 457–471.

Doyle, E., Frecknall-Hughes, J., & Summers, B. (2009). Research methods in taxation ethics: Developing the defining issues test (DIT) for a tax specific scenario. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 35–52.

Doyle, E., Frecknall-Hughes, J., & Summers, B. (2013). An empirical analysis of the ethical reasoning process of tax practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(2), 325–339.

Doyle, E., Frecknall-Hughes, J., & Summers, B. (2014). Ethics in tax practice: A study of the effect of practitioner firm size. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(4), 623–641.

Fleischman, G., & Stephenson, T. (2012). Client variables associated with four key determinants of demand for tax preparer services: An exploratory study. Accounting Horizons, 26(3), 417–437.

Fogarty, R., & Jones, D. (2014). Between a rock and a hard place: How tax practitioners straddle client advocacy and professional responsibilities. Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management, 11(4), 286–316.

Frecknall-Hughes, J., & Kirchler, E. (2015). Towards a general theory of tax practice. Social & Legal Studies, 24(2), 289–312.

Frecknall-Hughes, J., Moizer, P., Doyle, E., & Summers, B. (2017). An examination of ethical influences on the work of tax practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics, 146(4), 729–745.

Good, P. I. 2005. Resampling methods: A practical guide to data analysis (3rd ed.). Boston: Birkhäuser.

Gunz, S., & Thorne, L. (2017). Introduction to thematic symposium on accounting professionalism. Journal of Business Ethics, 142(2), 199–201.

Hackenbrack, K., & Nelson, M. (1996). Auditors’ incentives and their application of financial accounting standards. The Accounting Review, 71(1), 43–59.

Hume, E. C., Larkins, E. R., & Iyer, G. (1999). On compliance with ethical standards in tax return preparation. Journal of Business Ethics, 18(2), 229–238.

ICAEW. (2007). Reporting with integrity: Information for better markets initiative. London: ICAEW.

IESBA. (2016). Code of ethics for professional accountants. New York: IFAC.

IFAC. (2017). International standards: 2017 global status report. New York: IFAC.

IRS. (2009). Return preparer review. Washington DC: IRS.

Jenkins, J. G., Popova, V., & Sheldon, M. D. (2018). In support of public or private interests? An examination of sanctions imposed under the AICPA code of professional conduct. Journal of Business Ethics, 152, 523–549.

Johnson, L. (1993). An empirical investigation of the effects of advocacy on preparers’ evaluations of judicial evidence. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 15(1), 1–22.

Kadous, K., & Magro, A. (2001). The effects of exposure to practice risk on tax professionals’ judgments and recommendations. Contemporary Accounting Research, 18(3), 451–475.

Kadous, K., Magro, A., & Spilker, B. (2008). Do effects of client preference on accounting professionals’ information search and subsequent judgments persist with high practice risk? The Accounting Review, 83(1), 133–156.

Klayman, J. (1995). Varieties of confirmation bias. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 32, 385–415.

Levy, L. (1996). Evidence evaluation and aggressive reporting in ambiguous tax situations. Ph.D Dissertation, University of Colorado.

Libby, R. (1981). Accounting and human information processing: Theory and applications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lindblom, C., & Ruland, R. G. (1997). Functionalist and conflict views of AICPA code of conduct: Public interest vs. self interest. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(5), 573–582.

Maletta, M., & Zhang, Y. (2012). Investor reactions to the contrasts between the earnings preannouncements of peer firms. Contemporary Accounting Research, 29(2), 361–381.

Marshall, R. L., Armstrong, R. W., & Smith, M. (1998). The ethical environment of tax practitioners: Western Australian evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(12), 1265–1279.

Mason, J., & Levy, L. (2001). The use of latent constructs method in behavioral accounting research: The measurement of client advocacy. Advances in Taxation, 13, 123–139.

Metzger, L. (2011). The keys to integrity and a sense of well-being for accounting professionals. CPA Journal, 81(3), 10–12.

Mulligan, E., & Oats, L. (2016). Tax professionals at work in Silicon Valley. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 52(1), 63–76.

New York, NY: Birkhauser Boston.

Payne, D., & Raiborn, C. (2018). Aggressive tax avoidance: A conundrum for stakeholders, governments, and morality. Journal of Business Ethics, 147(3), 469–487.

Pinsker, R., Pennington, R., & Schafer, J. (2009). The influence of roles, advocacy, and adaptation to the accounting decision environment. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 21(2), 91–111.

Richardson, A. (2018). The accounting profession. In R. Roslender (Ed.), The Routledge companion to critical accounting (pp. 127–142). New York: Routledge.

Roberts, M. (1998). Tax accountants’ judgment and decision-making research: A review and synthesis. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 20(1), 78–121.

Sikka, P. (2009). Financial crisis and the silence of the auditors. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34(6–7), 868–873.

Spalding, A. D., & Lawrie, G. R. (2017). A critical examination of the AICPA’s new “conceptual framework” ethics protocol. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3528-0.

Spilker, B., Stewart, B., Wilde, J., & Wood, D. (2016). A comparison of U.S. and offshore Indian tax professionals’ client advocacy attitudes and client recommendations. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 38(2), 51–66.

Stephenson, T. (2007). Do clients share preparers’ self-assessment of the extent to which they advocate for their clients? Accounting Horizons, 21(4), 411–422.

Suddaby, R., Gendron, Y., & Lam, H. (2009). The organizational context of professionalism in accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34(3–4), 409–427.

West, A. (2018). After virtue and accounting ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(1), 21–36.

Wyatt, A. (2004). Accounting professionalism—they just don’t get it. Accounting Horizons, 18(1), 45–53.

Zeff, S. (2003a). How the U.S. accounting profession got where it is today: Part 1. Accounting Horizons, 17(3), 189–205.

Zeff, S. (2003b). How the U.S. accounting profession got where it is today: Part 2. Accounting Horizons, 17(4), 267–286.

Acknowledgements

This paper has benefitted from the detailed and helpful comments of the associate editor (Muel Kaptein) and three anonymous reviewers. We thank our participants and gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA).

Funding

This study was funded by the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (grant number 14ND27).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author Fatemi declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author Hasseldine declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author Hite declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Background Questions

Appendix 2: Real Estate Tax Case*

Assume a client, Jim Hunt, asks you whether he must classify some land sales as ordinary or capital. He believes it is an ambiguous tax issue and has asked for your opinion on how it should be reported. Once you have read the scenario, please respond to the follow-up questions regarding your beliefs.

Jim Hunt is the CEO of Delta Electronics, Inc., an important corporate client for whom we have done audit and tax work for many years. You are in the process of preparing Jim’s current income tax return and need to determine whether a $500,000 gain he realized on sales of real estate should be treated as ordinary or capital. I.R.C. Section 1221 defines a “capital asset” by exception. The relevant exception in this case is provided in Section 1221(1), which provides that “property held by the taxpayer primarily for sale to customers in the ordinary course of his trade or business” is NOT a capital asset.

If Jim’s real estate is considered a Section 1221(1) asset (i.e., Jim is viewed as a “dealer”), then the gain will be treated as ordinary. In contrast, if the property is not considered a Section 1221(1) asset (i.e., Jim is viewed as an “investor”), then the gain will be treated as a long-term capital gain. Obviously, Jim would prefer to be treated as an investor with respect to this property so that his gain will be taxed at the lower, alternative rate for long-term capital gains. Jim’s marginal tax rate on ordinary income is in the highest bracket, approximately 40%.

Summary of Factors

Factors considered by the courts as indicative of dealer vs. investor status are summarized below. Courts have stressed that no one factor is determinative and that each case must be considered on its own facts. Moreover, these factors have not always been applied on a consistent basis.

Remember that whether an asset is considered a Section 1221(1) asset affects the character of the taxpayer’s income or loss as follows:

Section 1221(1) asset: → Dealer → Ordinary Income or Loss

NOT Section 1221 (1) asset: → Investor → Capital Gain or Loss

Number and frequency of sales Generally, the greater the number of sales, the more frequent the sales, and the more continuity in sales activities, the greater the likelihood that the taxpayer will be considered a dealer.

Development activities Generally, the greater the development activities, the more likely the taxpayer will be considered a dealer.

Sales activities Generally, the more the taxpayer advertises, solicits customers, lists the property and otherwise promotes the sale of the property, the more likely the taxpayer will be considered a dealer.

Purpose of acquisition Generally, the purpose for which the property was originally acquired AND the purpose for which the property was held at the time of its disposition are important in deciding whether the taxpayer is a dealer or investor.

Please turn the page now to continue reading …...

Client Facts

On June 1, 2009, Jim Hunt purchased 40 acres of undeveloped land for $1.3 million. At the time, Jim was confident that the land would appreciate in value due to the planned construction of a regional shopping mall nearby. The land was already zoned for “retail/commercial” use and he hoped to sell the land in a single transaction after construction on the shopping mall began. Unfortunately, plans for the shopping mall fell through in early 2010, and Jim was unable to find a buyer for his property. He began placing advertisements in the local paper once a month, and he put on the property a “for sale” sign that was visible from the highway. Despite Jim’s sales efforts, he was unable to locate a buyer.

In June 2012, Jim decided that the property would be much more marketable if he subdivided the land into individual lots for residential development. Jim solicited the help of a friend (a real estate developer), part time, to assist him in the process of developing and selling the land, to be referred to as “Mountain View Estates.” Jim hired an engineer to plat the property into 110 individual lots and to determine the location of streets, etc. Jim submitted the engineer’s drawings to the City Planning Board along with his application to have the property’s zoning changed to “single family residential.” The zoning change was approved in September 2012. Jim incurred engineering and legal costs of $30,000 in this process.

In October 2012, Jim hired a contractor to build the necessary streets, curbs and drainage systems, and to connect the property to the city’s utility systems (e.g., water, sewer, and electricity). This development was completed by June 2013 at a total cost of $780,000.

Between August and October 2013, Jim sold six developed lots from the Mountain View Estates development for a total of $150,000. In October, a residential builder offered $2.5 million for the remaining 104 lots. Jim accepted the offer and ceased other sales activities. The sale was completed on November 1, 2013. After accounting for the property improvements and selling expenses, Jim had an overall gain of $500,000 computed as follows:

In January 2013, having become knowledgeable about residential land development, Jim decided to purchase and subdivide an additional 60 acres adjacent to Mountain View Estates. An engineer was hired to plat the land into 200 residential lots, known as “Mountain View Estates, Phase II” and the plans were approved by the City Planning Board in April 2013. In July 2013, Jim hired the same contractor who did the development work on Mountain View Estates to do similar work on Mountain View Estates, Phase II. The contractor constructed the streets, curbs and drainage systems for the Phase II development. The contractor also connected the Phase II lots to the city’s utility system. Although development of the Phase II lots was nearly complete by December 2013, none of the Phase II lots had been sold as of the end of 2013. Jim plans to begin selling the Phase II lots to individual buyers during 2014.

*This case was adopted from Cloyd and Spilker (1999).

Questions Related to the Case

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fatemi, D., Hasseldine, J. & Hite, P. The Influence of Ethical Codes of Conduct on Professionalism in Tax Practice. J Bus Ethics 164, 133–149 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4081-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4081-1