Abstract

Despite growing evidence of the benefits to a firm of improving corporate social performance (CSP), many firms vary significantly in terms of their CSP activities. This research investigates how the characteristics of the stakeholder landscape influence a firm’s CSP breadth. Using stakeholder theory, we specifically propose that several factors increase the salience and impact of stakeholders’ demands on the firm and that, in response to these factors, a firm’s CSP will have greater breadth. A firm’s CSP breadth is operationalized as the number of different sub-domains of CSR for which a firm has taken positive actions and is captured using a unique dataset from Kinder, Lydenburg, and Domini (KLD). This data set includes positive and negative firm actions across more than 35 different dimensions of socially responsible behavior. Findings based on a longitudinal, multi-industry sample of 447 US firms during the period from 2000 to 2007 demonstrate that firms which: (1) have greater sensitivity to stakeholder needs as a result of the firm’s strategic emphasis on marketing and/or value creation, (2) face greater diversity of stakeholder demands, and (3) encounter a greater degree of scrutiny or risk from stakeholder action have a greater breadth of CSP in response to the stakeholder landscape that they face.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Academic researchers have recognized and demonstrated the importance of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate social performance (CSP) to the market-related outcomes of a firm.Footnote 1 Previous research demonstrates that CSP has a strong influence on several intangible marketing assets of a firm. Specifically, a firm’s CSP leads to higher levels of customer identification with a company (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001); improved company evaluations which lead to improved product attitudes and evaluations (Brown and Dacin 1997; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001; Berens et al. 2005); increased differentiation from competition (Meyer 1999); the development of a reservoir of “goodwill” (Dawar and Pillutla 2000) or “moral capital” (Godfrey 2005) which generates an “insurance-like” protection against negative information (Godfrey et al. 2009); increased purchase likelihood, loyalty, and advocacy behavior (Du et al. 2007); and increased customer satisfaction, which, in turn, leads to a firm’s improved financial performance (Luo and Bhattacharya 2006).

Studies show that the benefits associated with CSP have not gone unnoticed by the top executives in firms. Nearly 75 % of executives believe their firms need to integrate CSP into their strategic decisions (The Economist 2008), and most executives recognize that their response to the challenge of CSP will have a significant impact on the future success of their organization (Lubin and Esty 2010). Given the high level of agreement among executives and the overwhelming evidence of the positive outcomes associated with CSP, we would expect to see a majority of firms focusing on developing strategies related to CSP. This, however, does not seem to be the case, as studies find that a majority of firms lack an overall plan for approaching CSP and delivering results (Berns et al. 2009), and, in fact, “most are flailing around launching a hodgepodge of business initiatives without any overarching vision or plan” (Lubin and Esty 2010, p. 44). This lack of direction is also reflected in the academic literature, as researchers have “failed to understand the underlying mechanisms or triggers that shape firms’ CSP” (Crittenden et al. 2011, p. 72). Fundamentally, then, a key question in the CSP literature is trying to understand the “‘why’ behind socially responsible practices” (Crittenden et al. 2011).

A possible answer to this question lies in stakeholder theory. Waddock and Graves (1997) explain “a company’s interactions with a range of stakeholders arguably comprise its overall CSP record” (p. 303). Furthermore, researchers argue that firm’s CSP activities are one of the few strategic levers that can be used to build and strengthen relationships with multiple stakeholders (Hoeffler et al. 2010), suggesting an important link between a firm’s CSP decision-making and the needs and demands of its various stakeholders. Therefore, we believe that, to develop an understanding of the “underlying mechanisms or triggers” behind firm CSP decisions (Basu and Palazzo 2008), it is critical to understand how a firm’s stakeholder landscape influences its CSP decisions.

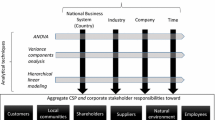

In the present research, we combine stakeholder theory and Ackerman’s three characteristic behaviors of responsive firms (1975) to address the following research question: What features of the stakeholder landscape are related to the breadth of a firm’s CSP? Specifically, based on Ackerman’s (1975) characteristics of stakeholder responsive firms, we propose that the following will predict the breadth of a firm’s CSP: (1) a firm’s sensitivity to stakeholder demands, (2) the diversity of stakeholder demands, and (3) exposure to stakeholder scrutiny or risk of stakeholder action. The conceptual model depicted in Fig. 1, and explained in the next section, illustrates the central hypotheses related to the key research question.

For several reasons, this study is important to further our understanding of the processes behind the decision to include CSP in an organization’s strategy. To the best of our knowledge, this study is among the very few that empirically examines the factors that are associated with firms’ CSP decision-making, and certainly one of the first to do so from the broader stakeholder theory approach (also see Jamali 2008). As such, we simultaneously answer a cross-disciplinary call to focus on the strategies employed in addressing a broad range of stakeholder interests (Parmar et al. 2010) and a call for research that attempts to explain the “‘why’ behind socially responsible practices” (Crittenden et al. 2011).

To summarize the findings of our research, we find that firms which (1) have greater sensitivity to stakeholder needs as a result of a strategic emphasis on marketing and/or value creation, (2) face greater diversity of stakeholder demands, and (3) encounter a greater degree of stakeholder scrutiny or risk from stakeholder action have a greater breadth of CSP in response to the stakeholder landscape that they face. In the following section, we explain the conceptual model for this study (illustrated in Fig. 1) and present hypotheses regarding the factors associated with positive CSP breadth. To develop these hypotheses, we draw on prior literature in several different business disciplines as well as previous empirical and theoretical CSP literature. We then test our hypotheses using secondary data. The third section presents the methodology of this study and includes descriptions of the sample and the measures and sources of data for all the variables. The fourth section of the paper focuses on the analysis of the data and the results. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of the results and their implications for theory and practice, the limitations of our study and future research directions.

Theory and Hypotheses

Stakeholder theory has its roots in the mid-1960s management literature, although the theory’s formalization is often credited to Freeman (Laplume et al. 2008), whose widely used definition of stakeholder theory states that managers, “must pay attention to any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the organization’s purpose, because that group may prevent [the firm’s] accomplishments” (Freeman 1984, p. 52). More generally, researchers have argued that stakeholders set norms for, experience the effects of, and evaluate corporate behavior (Ruf et al. 2001). Managers have the responsibility to safeguard the welfare of the corporation and balance the conflicting claims of multiple stakeholders (Evan and Freeman 1993), and it is, therefore, critical for managers to develop an understanding of the stakeholder landscape and identify those actors that can have a major impact on a company’s ability to serve the marketplace (Bhattacharya and Korschun 2008).

The critical literature on stakeholder theory generally agrees that developing mutually beneficial relationships with stakeholders is the key to an organization’s capacity to generate future wealth (Post et al. 2002; Choi and Wang 2009), and that failure to recognize the importance of a broader set of stakeholders will result in “big trouble” and “disastrous results,” sooner or later, for a firm’s future viability (Freeman 1984; Post et al. 2002; Smith et al. 2010). Researchers have drawn parallels between stakeholder theory and the resource-based view of the firm (Barney 1991) to explain the impact of a focus on stakeholders and argued that by responding to stakeholders’ demands, firms may gain a competitive advantage by developing skills and relationships with their stakeholders which, in turn, serve as valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources for the firm (Russo and Fouts 1997; Ruf et al. 2001; Ferrell et al. 2010).

One valuable approach to managing relationships with multiple stakeholders is for a firm to invest strategically in CSP. Previous research has argued that CSP initiatives are one of the key ways that firms can market themselves to multiple stakeholders, thus building and strengthening these relationships (Hoeffler et al. 2010). Others argue that the assessment of a firm’s CSP record is based on the extent to which a firm has met the needs of multiple stakeholders (Ruf et al. 2001), and the visible aspects of a firm’s CSP will be the basis on which the firm’s “motives will be judged, its use of responsive processes assessed, and its overall performance determined by stakeholders” (Wood 1991). Indeed, research shows that firms engaging consistently in CSP are able to signal information about the firm to external stakeholders in a manner that is difficult and costly to imitate, and that, over time, such firms may be able to build common ground and identity alignment with stakeholders who share similar values and interests (Meyer and Rowan 1977; Brickson 2007; Janney and Gove 2011). It is clear then that a firm’s ability to respond to multiple stakeholders is critical to its success, and there is evidence suggesting that CSP is one way that firms can manage stakeholder demands and develop a sustainable competitive advantage. However, it remains unclear which factors drive firms to identify and respond to stakeholder demands, specifically with respect to CSP.

Stakeholder theory suggests that the nature and values of an organization’s stakeholders, their influence on a firm’s decisions, and the nature of the situation are important factors when predicting organizational behavior (Brenner and Cochran 1991). Therefore, to address our key research questions, we develop a framework to link stakeholder theory and the factors that predict the breadth of a firm’s CSP in response to the demands of stakeholders.

Building on the characteristics of responsive firms, we argue that there are several factors related to the way firms (1) monitor the environment and stakeholder landscape and (2) attend to stakeholder demands that, in turn, drive a firm to (3) respond by increasing the breadth of its CSP in response to the characteristics of the stakeholder environment. As demonstrated in Fig. 1, we argue that there are sets of factors related to a firm’s ability and need to monitor, assess, or attend to stakeholders’ needs, and that these factors, in turn, determine the breadth of a firm’s CSP. Specifically, we examine factors that increase (1) a firm’s sensitivity to stakeholder demands, (2) the diversity of stakeholder demands placed on a firm, and (3) a firm’s exposure to stakeholder scrutiny or risks from stakeholder action. The following section explains our hypotheses with respect to each of these factors.

Sensitivity to Stakeholder Demands

The first category of factors contains the factors that are expected to increase a firm’s sensitivity to the demands of its stakeholders. We argue that marketing is the primary function within a firm that has the capability to recognize and respond to stakeholder demands; therefore, the importance placed on marketing in an organization will have an impact on the organization’s sensitivity to stakeholder demands. We use three factors to capture the importance placed on marketing within a firm and, thus, a firm’s sensitivity to stakeholder demands: (1) the presence of a chief marketing officer (CMO) in the top management team (TMT) of the firm, (2) a strategic emphasis on marketing, and (3) a strategic emphasis on value creation.

Corporate social performance is becoming increasingly important to firms’ customers and other external stakeholders (Bemporad and Baranowski 2007), and, as such, firms that are sensitive to the needs of these external stakeholders should be more focused on CSP. Marketing has been recognized as a boundary-spanning, outwardly focused function that can potentially monitor and incorporate stakeholders beyond the customer in creating value for the firm and society (Moorman and Rust 1999; Smith et al. 2010; Parmar et al. 2010). Furthermore, empirical evidence in marketing literature suggests that the key benefits of CSP to firms, as discussed previously, include the growth of the intangible assets that a firm’s marketing function is responsible for. Given their responsibility for managing marketing assets and their goal of maximizing stakeholder welfare (Iyer and Bhattacharya 2011), marketers should play a critical role in identifying opportunities related to stakeholder demands and CSP, and including CSP in a firm’s overall strategy to respond to these demands.

First, we argue that the importance of marketing within a firm will have a significant impact on the firm’s overall ability to scan and respond to the demands of external stakeholders. Research shows that management characteristics are critical to stakeholder responsiveness (Mitchell et al. 1997); however, managers vary greatly in their environmental scanning processes (Daft et al. 1988). Previous research suggests that marketing departments are responsible for considering the interests of all salient stakeholders, and that balancing these interests is more likely when the organization is marketing led (Smith et al. 2010). Several authors argue that the presence of a CMO in the TMT of a firm is strong evidence of the firm’s structural commitment to marketing, an indicator of both the corporate status of marketing and corporate adoption of the marketing concept, and a sign of a firm’s recognition (at the TMT level) of the importance of the customers’ and other external stakeholders’ voices (Webster Jr. et al. 2003; McGovern et al. 2004; Nath and Mahajan 2008). Fundamentally, there are three key roles of the CMO: (1) identifying new market opportunities and threats to guard against (informational), (2) deciding the level of investment to be made in activities associated with the marketing function (decisional), and (3) developing and managing relationships with external stakeholders (relational) (Boyd et al. 2010). These roles suggest that the CMO is the organization’s key figure for maintaining relationships with external stakeholders; therefore, firms with a greater structural commitment to marketing (in the form of a CMO in the TMT) will be more sensitive to the needs of external stakeholders, and such firms will be likely to have a greater breadth of CSP in response to the various demands placed on the firm by its stakeholders. Therefore, we hypothesize that firms with a CMO in the TMT will have greater breadth of CSP.

H1

Firms with a CMO in the TMT have a greater breadth of positive CSP.

Second, consistent with existing literature, we argue that a strategic emphasis on marketing is evidence of a firm’s commitment to marketing (Mizik and Jacobson 2003). Specifically, previous literature argues that a strategic emphasis on marketing is evident in the proportion of a firm’s spending dedicated to marketing, and that such investments will result in greater marketing capabilities, including improved understanding of the factors that influence choice behavior, enhanced abilities to monitor the environment, and an increased ability to build strong relationships with a firm’s external stakeholders (Dutta et al. 1999). Fundamentally, the previous literature argues that a strategic emphasis on marketing provides evidence of a firm’s commitment to the marketing concept, with its primary goal of creating value for the firm and society, and building relationships with a firm’s external stakeholders. Therefore, we argue that firms with a strategic emphasis on marketing will have greater CSP breadth.

Two methods of conceptualizing a firm’s strategic emphasis on marketing have been proposed in the literature: marketing intensity (Dutta et al. 1999; Mizik and Jacobson 2007) and advertising intensity (Mizik and Jacobson 2003; Luo and Bhattacharya 2009). Fundamentally, the two methods capture different characteristics of a firm’s strategic emphasis on marketing. Marketing intensity describes all elements of a firm’s promotional mix (Vinod and Rao 2000) and captures investment in a firm’s overall stock of marketing capabilities (Dutta et al. 1999), while advertising intensity describes the portion of the promotional mix dedicated to advertising only, given that advertising is typically the key communicator of corporate identity information to stakeholders, and the primary way for firms to develop brand-based differentiation and appropriate the value of their offerings (Mizik and Jacobson 2003; Luo and Bhattacharya 2009). Given the strong conceptual and empirical support for each method, we hypothesize that there will be differential impacts of each method on a firm’s overall CSP breadth.Footnote 2

H2a

Firms with greater marketing intensity will have a greater breadth of positive CSP.

H2b

Firms with greater advertising intensity will have a greater breadth of positive CSP.

Finally, the previous literature argues that firms with a strategic emphasis on value creation may develop stronger capabilities to create new products and offerings that satisfy the emerging needs of external stakeholders (Luo and Bhattacharya 2009). There is evidence that stakeholders respond to firms with enhanced innovative ability and greater CSP with greater positive perceptions and identification with the company (Brown and Dacin 1997), and that more innovative firms actually experience greater returns on their CSP (as a result of stakeholder confidence in both a firm’s ability to produce good products and attributions of good corporate management) (Luo and Bhattacharya 2006). Fundamentally, researchers find that value creation is a cornerstone of marketing, and that firms that engage in value-creation activities generate societal value as a result of the firm’s primary focus on creating offerings that meet the needs and demands of customers and other external stakeholders (Mizik and Jacobson 2003). We argue that a strategic focus on innovation, value creation, and external stakeholders will result in a firm that is more sensitive to stakeholder demands, and we hypothesize that this increased sensitivity to stakeholder demands will result in greater CSP breadth.

H3

Firms with a greater strategic emphasis on innovation will have a greater breadth of positive CSP.

Diversity of Stakeholder Demands

The second category of factors includes those that increase the diversity of stakeholder demands and, subsequently, impact the breadth of a firm’s CSP in response to these diverse demands. Specifically, we examine two sub-factors: serving consumer [vs. business-to-business (B2B)] markets and the firm’s degree of globalization.

There is a growing consensus among academics that a firm’s stakeholders are embedded directly and indirectly in interconnected networks of relationships through which the “actions of a firm reverberate with both direct and indirect consequences” (Rowley 1997; Bhattacharya and Korschun 2008). A vast majority of the work on CSP in the marketing and public policy literature focuses specifically on its impact on the consumer. However, recent work has bemoaned the fact that managers often fail to recognize the consumer as a multifaceted stakeholder; as “a citizen, a parent, an employee, a community member or a member of a global village with a long-term stake in the future of the planet” (Jocz and Quelch 2008; Smith et al. 2010). From this perspective, the consumer is likely to place a range of demands on firms as a result of the many different perspectives and responsibilities that consumers must balance. Indeed, a recent study of consumer concerns finds that more than 80 % of consumers reported all of the following as major concerns: access to healthcare, education and drinking water, fighting domestic abuse and violence, disaster relief, alleviating hunger and homelessness, human and civil rights, diversity, and fighting global pandemics. Furthermore, the same study finds that 87 % of global customers believe businesses should place equal weight on business and society and should be dealing with these key concerns in a balanced manner (Edelman 2012). Clearly, these results support the contention that consumers are, indeed, multifaceted stakeholders in their demands and concerns, and they expect firms to take these concerns into account. When a firm is faced with a diverse range of demands, past research shows that markets reward innovation and differentiation, a finding which increases the need to identify marketing opportunities quickly and correctly (Hambrick 1981; Hitt and Ireland 1985).

On the other hand, past research indicates that B2B customers make decisions as part of a committee, which decreases the impact of individual beliefs and perceptions (Lilien 1987). Furthermore, B2B customers have an increased focus on objective criteria (such as production schedules and costs) in their decision-making in an effort to satisfy a total organizational need, rather than individual wants (Lilien 1987). There is some evidence that B2B firms are beginning to demand greater CSP from their suppliers in particular domains (Lubin and Esty 2010). However, these customers largely demand cost cutting, quality improvement, and legal risk reduction measures (Joshi 2012), demands which may include socially responsible elements, but are unlikely to match the broad range of CSP demands from consumers. The evidence suggests that consumers are likely to place a more diverse set of CSP demands on firms and are more likely to respond to CSP than are B2B customers. Therefore, we hypothesize that firms that serve consumer (vs. B2B) markets will have a greater breadth of CSP in response to the diverse demands of these consumer markets.

H4

Firms that serve a consumer (vs. B2B) markets will have a greater breadth of positive CSP.

The second sub-factor in this category is the degree to which firms are globalized (i.e., depend on markets outside of the United States to generate sales). Firms that operate across multiple national boundaries face a variety of political, legal, economic and sociocultural systems, and CSP objectives and strategies must necessarily vary in order to conform to these systems (Windsor and Preston 1988). That is, a firm’s globalization is likely to create a diverse set of needs that a firm must meet in order to be successful in these international markets. Furthermore, for U.S. firms operating overseas, there is a strong expectation among foreign stakeholders of the firms’ social responsibility, rather than the inconsistent demand for social responsibility that firms typically experience in the United States market (Holt et al. 2004). Additional evidence suggests that stakeholder concerns are a critical force in driving the CSP of firms operating outside the United States (Berns et al. 2009; Cappelli et al. 2010). These findings suggest that serving markets outside of the United States is likely to increase the diversity of stakeholder demands with respect to CSP; therefore, we hypothesize that a higher degree of globalization will lead to a greater breadth of CSP.

H5

Firms that have a higher degree of globalization have a greater breadth of positive CSP.

Exposure to Stakeholder Scrutiny or Risk from Stakeholder Action

We focus next on factors that increase a firm’s exposure to stakeholder scrutiny or the risks and rewards of stakeholder action. Specifically, we focus on one factor that leads to greater scrutiny, firm size, and one factor that increases the risk from stakeholder action, corporate (vs. house-of-brands) branding strategy.

We propose that a firm’s exposure to stakeholder scrutiny is largely determined by the size of the firm. In a conceptual study, Udayasankar (2007) develops the argument that larger firms tend to have a larger social impact, given their scale of activities; therefore, stakeholders may place greater demands for socially responsible behavior on these firms and such firms may be at risk of suffering greater damage to their reputation due to inadequate levels of CSP (Udayasankar 2007). Indeed, previous research finds that as firms mature and grow they are subject to greater levels of scrutiny and “implicit regulation” from external stakeholders. As a result, they need to respond more openly to these demands and engage in more (and better) social performance initiatives (Chen and Metcalf 1980; Burke et al. 1986; Stanwick and Stanwick 1998). Evidence in the management literature suggests that a firm’s visibility confers greater pressure on a firm to respond to social and political pressure because stakeholders are likely to take a greater interest in organizations that directly affect them or of which they are aware (Meznar and Nigh 1995). This phenomenon is only enhanced by media attention influencing stakeholder preferences, which, in turn, shapes the public agenda and stakeholder pressure on firms (Erfle and McMillan 1995). Fundamentally, many argue that larger organizations, with their greater visibility, may be more sensitive to their stakeholders, have greater access to resources, and have more evolved administrative processes to perceive and deal with the external environment, each of which result in greater responsiveness to social issues (Brammer and Millington 2006). Therefore, we hypothesize that larger firms will have a greater breadth of CSP in response to the greater levels of stakeholder scrutiny that they experience.

H6

Larger firms will have a greater breadth of positive CSP.

In the marketing literature, branding strategies are often regarded as a continuum, ranging from corporate branding, which uses the corporate brand name for all of the firm’s products and services, to house-of-brands, where the corporate name is not used on any of the firm’s products and, instead, there are multiple brand names used to market individual products or groups of products (Rao et al. 2004). Some researchers argue that corporate branding has similar objectives to product-level branding in creating differentiation and preference (Knox and Bickerton 2003). However, rather than focusing exclusively on the end customer, the corporate brand faces the unique challenge of responding to the requirements of multiple stakeholders (Roper and Davies 2007). Furthermore, the use of corporate brands can increase a company’s visibility, recognition, and reputation in ways that are not possible through product-level branding, but this increased visibility also exposes a corporation to far greater scrutiny (Hatch and Schultz 2003) and generates a broader demand for a firm’s social responsibility (Knox and Bickerton 2003).

One of the benefits of corporate branding is that the positive outcomes associated with a firm’s strategic marketing actions, including CSP, are likely to carry over to all of the company’s products (Biehal and Sheinin 2007) and benefit the corporate brand as a whole (Rao et al. 2004). This transference of benefits increases the returns that the firm experiences as a result of its CSP, but also suggests that negative stakeholder responses to a firm’s actions may similarly carry over to all of the firm’s products. Some researchers argue that management must be sensitive to the increased risks associated with a corporate-branding strategy; therefore, that having a strong citizenship brand can be very helpful in mitigating risk (Aaker 2004). The risk management perspective offers a great deal of evidence to support this conjecture. Previous work suggests that, when negative events occur, stakeholders will respond with sanctions, ranging from boycotts or badmouthing to a complete revocation of the firm’s legitimacy, or right to do business, based on the stakeholders’ attributions about the firm’s motivation (Ellen et al. 2006; Godfrey et al. 2009). A firm’s engagement in positive CSP has the ability to signal a partially altruistic orientation (at minimum) and should reduce the overall severity of these sanctions by “encouraging stakeholders to give the firm the benefit of the doubt regarding intentionality, knowledge, negligence, or recklessness” (Godfrey 2005). On the other hand, firms that are not actively engaged in positive CSP will not have established this “goodwill” and, as a result, be at risk of encountering repercussions as a result of negative CSP. When combined with the above-described positive impacts of CSP, this reduction in risk creates a situation in which firms with a corporate brand can expect to benefit from expanding CSP. For this reason, we expect that firms using a corporate-branding strategy will have a greater breadth of CSP.

H7

Firms with a corporate branding strategy will have a greater breadth of positive CSP.

In addition to the direct effect of corporate branding on a firm’s CSP breadth, we argue that the presence of a corporate brand may interact with some of our other predictors to produce an even greater CSP breadth. That is, Lawrence and Lorsch (1967) argue that certain strategic initiatives by firms, including CSP, may be more advantageous under particular environmental conditions. We believe the factors that (1) increase the diversity of stakeholder demands (i.e., serving consumer markets and degree of globalization) and (2) increase stakeholder scrutiny (i.e., firm size) may increase the risks faced by a firm with a corporate brand. Therefore, using the logic above, we argue that firms with a corporate brand and that also face these additional factors will have a greater breadth of CSP.

As firms face a greater diversity of stakeholder demands, they face increasing challenges associated with satisfying the requirements of their stakeholders (Hatch and Schultz 2003). Fundamentally, as stakeholder diversity increases, firms face an increased risk of, at minimum, failing to address stakeholder needs and, at worst, violating the expectations of important stakeholder groups. Thus, as the diversity of stakeholders increases, firms with a corporate brand face an increased risk of such failures, and, thus, should be more likely to have a greater breadth of CSP in an attempt to meet diverse stakeholder demands. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H8

For firms with a corporate brand, those that serve a consumer market will have greater a breadth of positive CSP.

H9

For firms with a corporate brand, those with a higher degree of globalization will have a greater breadth of positive CSP.

Finally, using similar logic, firms with a corporate brand that face higher levels of stakeholder scrutiny over their actions are likely to take additional steps to ensure that they minimize the risks associated with negative information. Consequently, these firms should be more likely to increase their CSP breadth in an effort to capture the previously discussed “insurance-like” benefits associated with CSP (Godfrey 2005). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H10

For firms with a corporate brand, those that face greater scrutiny (larger firms) will have a greater breadth of positive CSP.

Methodology

Sample

To address our key research question, we use the Kinder, Lydenburg, and Domini (KLD) Stats database, which measures the social and environmental performance of 4,000 firms along the dimensions noted in Appendix. According to the KLD website, some 400 money managers and institutional investors (including 31 of the top 50 institutional money managers worldwide) use either the KLD Stats database or the Domini 400 Social Investment Index (derived from KLD Stats) in their investment decision-making process. This database has been validated, used rather extensively in the management literature (Graves and Waddock 1994; Sharfman 1996; Waddock and Graves 1997; McWilliams and Siegel 2000; Hillman and Keim 2001) and described as “the standard for quantitative measurement of corporate social action” (Mattingly and Berman 2006).

As mentioned previously, the use of this data set provides several benefits over other measures that have been employed in the CSP literature. First, a number of studies use measures of social responsibility that focus on single domains of CSP (for example, compliance with particular environmental laws, operating decisions in South Africa, and philanthropic contributions, among many others) (Margolis and Walsh 2003). The dependent variable, in our case, captures seven dimensions of social performance, each of which is broken into several sub-domains. Sub-dividing the dependent variable allows us to capture more accurately a firm’s CSP across a broad range of domains, which is critical (both theoretically and practically) in improving our understanding of CSP breadth. Second, a number of other studies use broad company-level measures of CSR reputation, which capture perceptions of a firm’s behavior, rather than the actual behavior of a firm. These measures of perceived behavior may suffer from several well-documented perceptual biases, including a “halo effect” of a firm’s performance which can influence perceptions of a firm’s social responsibility (Waddock and Graves 1997). The KLD Stats database is based on the actual and reported behavior of firms; therefore it is not subject to the same biases as perceptual measures. Finally, the measures typically used in CSP studies come from a single data source, which could result in either a view of CSP that is too narrow, or a view of CSP that reflects the biases of the original data-collecting agent. Use of the KLD measures serves to reduce these potentially negative effects by aggregating data from a broad range of independent sources. The data sources are collected through direct communication with company officers, communication with a global network of CSR research firms, and through monitoring more than 14,000 global news sources, corporate proxy statements, quarterly and annual reports, and government and NGO information.

The KLD Stats database includes firm social performance information on seven dimensions: community relations, employee relations, product issues, corporate governance, diversity, human rights issues, and environmental performance. Each of these dimensions consists of a series of different sub-domains (for a breakdown of the categories, see Appendix). These sub-domains are further broken down into positive and negative actions by firms that are represented by binary scores of either zero (for actions the firm has not taken) or one (for actions the firm has taken) for each year in the database. Importantly, negative ratings do not preclude receiving positive ratings in a particular sub-domain, as the positive and negative dimensions are scored separately. This scoring method is consistent with previous research which demonstrates that the KLD measures of positive and negative actions are empirically and conceptually distinct (Mattingly and Berman 2006).

For the purpose of the present research, we focus on public firms in the United States and draw the original sample from all S&P 500 firms in the KLD Stats database, as these companies have been tracked consistently over the lifespan of the database. The KLD Stats database was augmented with data from S&P’s COMPUSTAT database, which includes firm financial data gathered from quarterly and annual reports, and which was used to capture several of the measures of interest for this study, including firm globalization, advertising intensity, R&D intensity, marketing intensity, and several of our control variables.

The final data sources used for this study include firm websites, annual reports, and proxy statements, from which we capture data for several of our hypotheses through a content analysis. Specifically, information on the presence of a CMO in the TMT of a firm, branding strategy, and types of markets served were captured through a content analysis of these data sources. The actual process of collecting each of these variables will be discussed in the next section.

The sample used in our analysis includes 447 firms, which were observed over the 8-year period from 2000 to 2007, inclusive (yielding 3,198 firm-year observations). For these 447 firms, we were able to obtain data on the independent variables of interest, either through S&P’s COMPUSTAT or through our own secondary data collection efforts. Our sample represents a cross-section of industries across 54 two-digit SIC codes.

Data Sources and Measures

Table 1 gives a brief summary of the data sources and measures used in the present study, described in greater detail below.

Dependent Variable: CSP Breadth

As indicated above, the dependent variable for this research is the breadth of a firm’s positive CSP and is based on the categories used in the KLD Stats database. The KLD Stats database identifies positive actions as those that exceed minimum legal or social requirements, and negative actions as those in which a firm fails to meet minimum legal or social requirements in a particular dimension. Consistent with our definition of CSP, we have chosen to use the number of sub-domains in which a firm has taken a positive action in a given year as a measure of the firm’s positive CSP breadth. Practically speaking, our work focuses on what drives firms to go above and beyond the baseline legal or social requirements across a broad range of CSP dimensions. Given the structure of the data (as a series of binary variables indicating the presence or absence of an action in a particular sub-domain), our dependent variable is the sum of these binary variables. In each year of our focus period, between 77 and 89 % of firms in our sample had positive ratings in at least one positive CSP dimension. Tables 2 and 3 present descriptive statistics and correlations for all measures. Our dependent variable is operationalized as the number of sub-domains of positive CSP for each firm.

Predictor 1: Sensitivity to Stakeholder Demands

Our first measure representing sensitivity to stakeholder demands is the presence or absence of a CMO in the company’s TMT. Our study follows the work of Nath and Mahajan (2008) in conceptualizing this factor as a binary variable for each year (the variable equals one if a firm has a CMO in the TMT in that year and zero otherwise). Specifically, an executive in the TMT with marketing in his/her title constitutes CMO presence; a TMT without such an executive represents CMO absence. For the purposes of this study, CMO equivalent titles include Vice President (VP) of Marketing, Senior VP Marketing or Executive VP Marketing (Nath and Mahajan 2008). CMO presence coded from the proxy statements was cross checked against the list of officers from annual reports, whenever possible. The summary statistics in Table 2 show that there was a CMO present in 17 % of our firm-year observations across all periods. Additional analysis showed that nearly 35 % of the firms in our sample had a CMO for at least 1 year of the sample, which is relatively consistent with the 42 % reported in previous literature (Nath and Mahajan 2008).

The second factor that we examine with respect to firm sensitivity to stakeholder demands is a firm’s strategic emphasis on marketing. As mentioned previously, there are, traditionally, two approaches to measuring strategic emphasis marketing: marketing intensity and advertising intensity, both of which are used extensively in recent literature. Marketing intensity is calculated as the ratio of SG&A spending less R&D spending to total revenue (Mizik and Jacobson 2007; Luo 2008; Krishnan et al. 2009; Morgan and Rego 2009). Advertising intensity is calculated as the ratio of advertising spending to total revenue (Mizik and Jacobson 2003; McAlister et al. 2007; Luo and Bhattacharya 2009). Marketing intensity has two primary advantages over advertising intensity: (1) SG&A spending is reported much more frequently than advertising and R&D spending (this issue is addressed in our discussion below on missing data) and (2) reported advertising data does not include other promotion or commercialization efforts—such as direct sales, trade promotions, market research, and related activities—which can be an issue in industries where commercialization is primarily achieved through methods other than advertising. We employ separate models for each of these variables, including marketing intensity in model A and advertising intensity in model B. Overall, Table 2 shows that the average firm in our sample spends 4 % of its revenue on advertising, while the average firm spends about 20 % of its revenue on general marketing expenses.

The last factor that we examine with respect to firm sensitivity to stakeholder demands is a firm’s strategic emphasis on value creation, operationalized as the R&D intensity of the firm. R&D intensity has been used in several studies (Mizik and Jacobson 2003, 2007; Krishnan et al. 2009; Luo and Bhattacharya 2009) and is operationalized as the ratio of R&D spending to the total revenue of the firm. The summary statistics in Table 2 show that, in our sample, the average firm spends about 8 % of its revenue on R&D.

The data used to generate marketing intensity levels, advertising intensity levels, and R&D intensity variables came from COMPUSTAT. One empirical concern with these variables is that COMPUSTAT tends to have a large amount of missing data on advertising, R&D, and SG&A, as firms are not required to report immaterial spending amounts in their annual reports. In our data, we see that, in any given, year 54–64 % of advertising, 35–38 % of R&D, and 12–15 % of SG&A data are missing. Consistent with previous literature using this data (Villalonga 2004; Luo and Bhattacharya 2009), we proceed by inserting zeroes for missing values and include dummy variables that equal one if the values of advertising, R&D, or SG&A are missing in order to control for unobservable factors that may be correlated with non-reporting of data.

Predictor 2: Diversity of Stakeholder Demands

The type of market served (consumer vs. B2B) variable was coded from firm websites and annual reports. Firms’ customer profiles were coded as being either pure B2B, pure B2C, or mixed. We coded each profile as a binary variable that equals one if the firm serves consumer markets (either B2C or mixed) and zero if the firm serves a pure B2B market. The customer profile of a firm tends to be stable over time; however, we checked across years to confirm that customer profiles remained constant for all firms. We find that 52 % of the firms in our sample serve consumer markets and 48 % serve pure B2B markets (see Table 2).

A firm’s degree of globalization is operationalized as the percentage of total sales designated as international sales (Sullivan 1994). Overall, our sample shows that, on average, 28 % of firm sales come from outside the United States, with a range from 0 to 93 % across our sample of firms (see Table 2).

Predictor 3: Exposure to Stakeholder Scrutiny or Risk of Stakeholder Action

For our measure of firm size, we tested both the natural log of sales and the natural log of the total number of employees and find that the choice of either control for firm size does not have a significant impact on parameter estimates. Therefore, we choose to report models using only the log of total employees as our control for firm size.

Finally, the corporate vs. house-of-brands branding strategy variable was based on the definitions presented by Rao et al. (2004). We operationalize branding strategy as a binary variable that equals one if a firm uses a corporate-branding strategy and zero otherwise. The branding strategy of a firm tends to be stable over time; however, as with customer profiles, we checked across the years in the sample to confirm that branding strategies remain consistent for each firm. As reported in Table 2, 50 % of our sample employed a corporate-branding strategy, while 50 % employed either a mixed or house-of-brands strategy.

Controls

The first control variable we include in our model is a firm’s breadth of negative CSP. In an unpublished manuscript, Kotchen and Moon (2007) argue that firms that have more negative CSP are likely to attempt offsetting this negative CSP by increasing positive CSP. In line with our arguments about the risks faced by firms with a corporate-branding strategy, we believe that firms with greater negative CSP breadth will indeed focus on increasing their breadth of positive CSP in an effort to mitigate some of the risks associated with potential sanctions from stakeholders as a result of their negative CSP. Using the KLD Stats database to capture a firm’s breadth of negative CSP, we record the total number negative CSP sub-domains for a firm in a given year.

In our model, the next two control variables of firm CSP breadth capture past financial performance. There is evidence in the literature indicating that a firm’s slack resources may be a strong predictor of CSP, given that firms with more free resources will be more able to spend money on increasing their CSP (Surroca et al. 2010). Thus, we control for past levels of return on assets (ROA) (measured as profits as a proportion of total assets) as a measure of slack resources. We also examined measures such as return on sales (ROS) and log of profits, yet found no significant difference between these measures in terms of their effects on our estimates. Consequently, we use ROA in our final model. As an additional control for the past performance of a firm, we include the value of Tobin’s q in the previous year. Tobin’s q is based on a firm’s stock market capitalization of a firm that, given the efficient markets hypothesis, ostensibly captures all available information about the firm’s future cash flow prospects (Fama 1970). Including this variable allows us to control for all known information pertaining to the years prior to the current period, including factors that are unobservable in our data and which may have an impact on the firm’s overall financial performance (and, in turn, on its breadth of positive CSP). Consistent with previous literature, we use the approximation proposed by Chung and Pruitt (1995) for Tobin’s q (Nath and Mahajan 2008), the formula for which is included in Table 1.

Our fourth control variable is whether or not a firm is a market leader in its particular industry during a given year. Typically, market leaders are larger firms and may receive a higher level of scrutiny from stakeholders, which, in turn, may push the firm to behave in a more socially responsible manner (Stanwick and Stanwick 1998). We operationalize market leadership as a binary variable which equals one if a firm has the highest level of sales in its industry (at the 2-digit SIC level) in a given year and zero otherwise.

Our fifth control variable is market turbulence. Market turbulence is identified in many studies as an important determinant and moderator of the effectiveness of firms’ different marketing strategies (Slater and Narver 1994; Moorman 1995). Our measures of market turbulence include both the coefficient of variation in sales growth and the coefficient of variation in ROA growth for a firm’s industry (Haleblian and Finkelstein 1993) and we find little difference between the two measures in terms of explanatory power. Given other variables in our model, we use the coefficient of variation in a firm’s industry sales growth as our measure of market turbulence.

It is both theoretically and empirically important to control for the unobservable effects of a firm’s industry, as it is likely that there are different levels of competitive and normative pressures that result from the industry in which a firm operates and that may drive a firm’s CSP. Such a control also allows us to correct for potentially spurious relationships between our independent variables (e.g., the type of customer market served) and the breadth of a firm’s CSP, both of which may be related to the industry in which a firm operates. As reported in Table 4, there is a great deal of variation across industries in terms of the breadth of CSP, and it is critical to try to control for unobservable causes of variation across industries. Therefore, we add a series of fixed-effect dummy variables for the industry in which a firm operates (by 2-digit SIC) as a set of controls. Consequently, all of our variables of interest enter our analysis as scores relative to the industry mean on each variable.

Similar to the potential for bias posed by the unobservable effects of a firm’s industry, failure to control for the year of an observation may result in a failure to capture firms’ generally increasing trends toward CSP, as well as other time-dependent, unobservable characteristics of the environment, thus potentially introducing bias into our estimates. As Fig. 2 clearly demonstrates, there is an increase over time in the average breadth of CSP across the years of the sample, particularly after 2005. We examined possible explanations for this slight jump after 2005 and find that 62 % of firms showed an increasing breadth of CSP across the sample. This statistic suggests that there was generally increasing CSP breadth over time that was not driven by the actions of a few outlier firms.Footnote 3 Given this generally increasing trend, we include a series of year fixed-effect dummy variables to control for unobservable environmental factors over time that may influence our observed CSP breadth. This refinement further adjusts our variables of interest, such that they are treated in the final regression as scores relative to a firm’s industry for each year in our sample.

Analysis and Results

As Table 4 shows, only one correlation between variables exceeds 0.4,Footnote 4 so we have little evidence of significant multicollinearity issues among our explanatory variables. We also examined the variance inflation factors (VIFs) associated with our independent variables, none of which exceed 2.0, which provide further evidence of a minimal impact of multicollinearity (Kennedy 2008).

Based on the structure of our conceptual model and the variables that we have chosen to include, we estimate our model using the following equation:

where CSP, breadth of positive CSP (no. of sub-domains of positive CSP); CMO, the presence of a CMO; MktgIntensity, marketing intensity/strategic emphasis on marketing; RDIntensity, R&D intensity/strategic emphasis on value creation; Consumer, consumer markets served; Global, degree of globalization; Size, firm size; CorpBrnd, the presence of a corporate branding strategy; NegCSP, breadth of negative CSP; ROA it − 1, return on assets in the previous year for firm i; Q it – 1, Tobin’s q in the previous year for firm i; MktLead, market leadership for 2-digit SIC; MktTurb, coefficient of variation in sales growth for 2-digit SIC; μ j and ξ t , industry and year fixed effects, respectively; ε it , firm-year specific error term.

In addition to including industry and year fixed effects, we expect that there will be within-firm dependence in our yearly observations due to the panel structure of our data. Ideally, including firm fixed effects would be the strongest correction for this within-firm dependence; however, the inclusion of firm fixed effects does not allow for the estimation of the effects of time-invariant, firm-specific (or relatively time-invariant) explanatory variables in our model of CSP breadth. Therefore, we introduce a robust or Huber–White estimator clustered at the firm level to correct for the downward bias in the standard errors that would result from the failure to correct for the within-firm dependence of our observations (Wooldridge 2002).

Results

Overall, the results of Eq. 1 estimation provide statistical support for all but two of our hypotheses. The results of our model of CSP breadth are included in Table 5. Model A includes marketing intensity while model B includes advertising intensity as the measures of a firm’s strategic emphasis on marketing. Finally, model C includes the interactions of a firm’s corporate-branding strategy with factors that (1) increase the diversity of stakeholder demands (i.e., serving consumer markets and increased degree of globalization) and (2) increase stakeholder scrutiny (i.e., firm size). In model C, we keep marketing intensity as our key measure of strategic emphasis on marketing given the results of models A and B. The results indicate good fit for both models A and B, with model A describing slightly more variance than model B (model A: R 2 = 0.380, model B: R 2 = 0.376). The results of all three models demonstrate strong support for H2a, that firms with greater marketing intensity have greater breadth of positive CSP (p < 0.01), while in model B, we find no support for H2b, which states that firms with greater advertising intensity have a greater breadth of CSP. Our discussion below will be based on the results of model C (except where noted), which includes marketing intensity and the three interaction terms and explains an additional 1.1–1.5 % of variance in firm CSP breadth over models A and B, respectively (model C: R 2 = 0.391).

Table 5 shows that we find directional (but not statistically significant) effects of CMO presence on a firm’s CSP breadth (p < 0.20). We find strong support for H2a, that firms with greater marketing intensity have greater breadth of positive CSP (p < 0.01). With respect to H3, we find strong statistical support that firms with higher R&D intensity also have a greater breadth of CSP (p < 0.01); similarly, we find strong statistical support for H4, that firms serving consumer markets have a greater breadth of CSP (p < 0.01). We also find statistical support for H5, which predicts that firms with a greater degree of globalization will have a greater breadth of CSP (p < 0.05). Moreover, our results also support H6; we find strong statistical evidence that larger firms have a greater breadth of positive CSP (p < 0.01). With respect to the hypothesized effects of corporate branding on CSP breadth, we find strong support in models A and B for H7 (p < 0.01), which predicts that firms with a corporate branding strategy have greater CSP breadth. When we include the interactions of corporate brand with degree of globalization and firm size in model C, we find only directional support for H7 (p < 0.20), a main effect that firms with corporate brands have greater CSP breadth. However, when we include the above interaction effects in model C, we find evidence of more nuanced effects for the impact of a corporate branding strategy on a firm’s CSP breadth. Specifically, we find statistical support for H9 (p < 0.05), which predicts that more globalized firms with a corporate brand have a greater breadth of CSP. We also find statistical support for H10 (p < 0.05), which hypothesizes that larger firms with a corporate brand have a greater breadth of CSP. Finally, with respect to our control variables, we find that firms with greater negative CSP breadth, and firms with higher financial performance in the past (both ROA and Tobin’s q) have a greater breadth of positive CSP.

Overall, the results of this model support two of our four hypotheses regarding the impact of sensitivity to stakeholder needs and demands on a firm’s CSP breadth (H2a and H3). We also find support for both of our hypotheses regarding the impact of increased diversity of stakeholder demands on a firm’s CSP breadth (H4 and H5), and both of our hypotheses with respect to firm exposure to stakeholder scrutiny or risk from stakeholder action on firm’s CSP breadth (H6 and H7). Furthermore, we find evidence of an interaction between (1) the diversity of stakeholder demands (H9) and (2) exposure to stakeholder scrutiny (H10) and a firm’s corporate brand strategy, offering a more nuanced understanding of how factors that increase the risks from stakeholder action against the firm, in turn, drive greater CSP breadth. Overall, these findings support our contention that the characteristics of the stakeholder landscape are important drivers of a firm’s CSP breadth.

Discussion and Implications

The purpose of this research was to address the following research question: What features of the stakeholder landscape are related to the breadth of a firm’s CSP? Our conceptual model proposes that factors increasing: (1) a firm’s sensitivity to stakeholder demands; (2) the diversity of stakeholder demands placed on the firm; and (3) a firm’s exposure to stakeholder scrutiny or risk of stakeholder action are positively related to the breadth of a firm’s CSP. Overall, we find support for a majority of our hypotheses, demonstrating that firms which: (1) have greater sensitivity to stakeholder needs as a result of a strategic emphasis on marketing and/or value creation; (2) encounter greater diversity in their stakeholder demands; and (3) face a greater degree of stakeholder scrutiny or risk from stakeholder action have a greater breadth of CSP.

Fundamentally, when firms focus on CSP as part of their strategic business model, they have the option of “going vertical” (i.e., focusing many CSP initiatives on one particular domain) or “going lateral” (i.e., spreading their CSP initiatives across many different domains).Footnote 5 In essence, our findings suggest that firms that are sensitive to stakeholder needs, faced with diverse stakeholder demands, and exposed to greater scrutiny and the potential risk of stakeholder responsiveness, in turn, respond by increasing the breadth of their CSP (i.e., “going lateral”). Therefore, our results demonstrate that, among firms with the broadest CSP, sensitivity and responsiveness to the diversity of stakeholder demands are important influences on their CSP decision-making. More specifically, we demonstrate that firms with a stronger strategic emphasis on marketing and value creation, and that face a greater diversity of stakeholder demands (either from consumer or globalized customer bases), respond with greater CSP breadth. We also demonstrate that firms that are exposed to greater scrutiny (i.e., larger firms) and firms that are exposed to greater risk from stakeholder actions (i.e., corporate branding strategy) also respond with greater CSP breadth. Furthermore, we show that firms that have a corporate branding strategy and that face greater diversity of stakeholder demands (or greater scrutiny) respond with an even greater breadth of CSP.

Implications for Theory

First, using firm CSP as a context, we provide empirical evidence that firms are behaving in ways consistent with the predictions of stakeholder theory. More specifically, we find evidence that firms that are sensitive to diverse stakeholder demands and that are exposed to greater scrutiny or risk of actions from their stakeholders, are responding with a greater breadth of CSP. Much of the discussion surrounding stakeholder theory has been focused on normative reasons explaining why firms should focus on their stakeholders, yet these discussions often neglect to offer an empirical investigation of whether or not firms are actually behaving in ways consistent with theoretical predictions (Berman et al. 1999). In fact, our review of the literature uncovered only one study that examines firm behavior for evidence of a broader stakeholder perspective: a working paper that investigated the websites of a random sample of one hundred Fortune 500 firms and finds that 66 of them mentioned either “maximizing the well-being of all stakeholders” or “solving social problems while making a fair profit” (Agle and Agle 1997). Our work is one of the first empirical studies on the behavior of firms from the perspective of stakeholder theory, answering a call in the previous research to focus on strategies for addressing a broad range of stakeholder interests (Parmar et al. 2010) and to advance the descriptive and empirical realm of theory by developing an understanding of how managers actually respond to stakeholders (Berman et al. 1999).

Second, we contribute to the CSP literature by being one of the first empirical studies to examine factors associated with firm CSP decision-making. In doing so, we answer a cross-disciplinary call for research that captures the “why behind socially responsible practices” and that develops a base of descriptive, empirical knowledge with respect firms’ inclusion of CSP in their strategic decisions (Donaldson and Preston 1995; Margolis and Walsh 2003; Crittenden et al. 2011).

Implications for Practice

From discussions in the academic literature and in the popular press, it seems that the demand for a broader stakeholder perspective is growing in the world of corporate management. Our results support this observation by providing evidence that characteristics of the stakeholder landscape are influencing firms’ strategic behavior (from the perspective of CSP). We find strong evidence that firms with an emphasis on marketing (either a strategic emphasis on marketing or value creation), and a focus on the diverse needs of external stakeholders, are leveraging the strengths and capabilities developed over the previous several decades to become major participants in, or perhaps leaders of, two important movements in the corporate world: the evolution toward a broader stakeholder perspective and the movement toward greater CSP by firms. Since as far back as Freeman (1984), stakeholder theory scholars have argued that marketing is “an outwardly focused discipline, and thus it is in a strong position to work on problems associated with external stakeholders” (Parmar et al. 2010, p. 426) and that marketing tools, such as segmentation techniques, should be used to categorize the multiple stakeholders of the firm and, thus, better understand their interests and predict their behaviors (Laplume et al. 2008). Our results provide evidence that, for firms with the greatest breadth of CSP, marketing is indeed proactively involved in the management of relationships with multiple stakeholders. The empirical results of our research suggest that firms that have a strategic emphasis on marketing and on value creation have greater CSP breadth. Interestingly, we also do not find any evidence that a structural commitment to marketing at the highest levels (as evidenced by the presence of a CMO in the TMT) results in a greater CSP response to the demands of a firm’s many stakeholders. When combined, these results suggest that firms that have a broader and more strategic organizational commitment to marketing appear to be doing more to improve their CSP than firms that have a CMO, a finding which is consistent with previous arguments, that for firms to see the positive effects of CSP, they must implement a broad strategic commitment across their entire organization (Porter and Kramer 2006; Lubin and Esty 2010).

Fundamentally, based on these arguments and our empirical findings, the argument can be made that firms which recognize the wants and needs of stakeholders can potentially improve future opportunities, and that marketing is ideally positioned to aid in the pursuit of satisfying the demands of multiple stakeholders. On the other hand, a firm’s failure to recognize the impact that various stakeholders can have on its outcomes may significantly handicap its future opportunities. Specifically, a firm’s simultaneous movements toward a broader stakeholder perspective and greater CSP can create a sustainable competitive advantage for a firm (Russo and Fouts 1997) as well as generate improved financial performance over a longer period of time, reduce costs, increase access to new markets, increase a firm’s ability to innovate, and avoid the risk associated with negative events (Bhattacharya and Korschun 2008; Choi and Wang 2009; Godfrey et al. 2009).

Limitations and Further Research

First, this study takes initial steps toward understanding the factors that lead a firm to have a greater breadth of CSP. One desirable extension of this work, both academically and practically, is to expand the group of factors examined in order to develop a deeper understanding of which additional characteristics of the firm, its stakeholders, and its competitive environment drive firms’ CSP breadth and depth. For example, it may be that past positive and negative action of a firm, the presence of institutional activist investors on the board, lawsuits over firm actions, media pressure, the personal interests of the CEO, the market orientation of a firm, and other considerations are related to the observed breadth and depth of CSP. While our results provide strong evidence indicating the importance of responsiveness to stakeholders in firms’ decisions regarding CSP, there are almost certainly additional variables that are likely to affect these decisions.

Second, an important question which the previous literature neglects to answer is, “When and where does CSP pay off?” It is possible that CSP pays off differently for firms in different industries and for firms that have different stakeholder characteristics. Once the factors explaining why firms pursue CSP within their organizations are established, it is very useful to understand whether or not CSP disproportionately benefits firms that have a combination of these particular factors. The focus of the present work was on trying to understand the first part of this question and to capture why firms engage in socially responsible practices; however, there is certainly a great deal of value in understanding when and where CSP pays off.

Finally, this study measures CSP across multiple domains to understand the factors that influence a firm’s breadth of CSP. Given the multidimensional nature of CSP, it is entirely possible that a firm’s performance in individual dimensions of CSP may be differently affected by a firm’s characteristics and the stakeholder demands it faces. It is also possible that stakeholders and decision makers have very different expectations of the outcomes associated with individual dimensions of CSP. Therefore, it would be useful to take the present research a step further by attempting to understand how the various dimensions of CSP are differently influenced, the different demands of various stakeholder groups (and how firms respond to them), and the extent to which CSP in each of these domains does, in fact, translate into the manager’s or stakeholders’ expected outcomes.

Notes

For the purpose of the present study, we define CSR as defined in Hopkins (2007): “CSR consists of voluntary initiatives taken by companies over and above their legal or social obligations that integrate societal and environmental concerns into their business operations and interactions with their stakeholders.” Previous research has argued that it is the visible aspects and outcomes of a CSR program on which a company’s motives will be judged, its use of responsive processes assessed, and its overall performance determined by stakeholders (Wood 1991). CSP is an outcome measure of the visible aspects of the implementation of policies and programs intended to reach the overarching goal of CSR. Therefore, we examine the actual behavior of firms, and the remainder of the paper will focus on and refer to a firm’s CSP.

Despite the significant conceptual overlap between the two measures, our “Methodology” section will show that formal tests for multicollinearity indicate that these measures are significantly non-overlapping, and each measure is tested separately in our estimated models.

Further analysis shows that removing outliers does not significantly change the averages demonstrated in Fig. 2.

The only correlation that exceeds 0.4 is between SG&A and Advertising spending, which is acceptable and expected given that SG&A includes Advertising spending in addition to several other types of marketing spending including marketing research, sales effort, trade promotions and related activities (Dutta et al. 1999).

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this comment.

References

Aaker, D. A. (2004). Leveraging the corporate brand. California Management Review, 46(3), 6–18.

Ackerman, R. W. (1975). The social challenge to business. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Agle, B., & Agle, L. (1997). The stated objectives of the Fortune 500: Examining the philosophical approaches that drive America’s largest firms. Working paper, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Basu, K., & Palazzo, G. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: A process model of sensemaking. Academy of Management Review, 33(1), 122–136.

Bemporad, R., & Baranowski, M. (2007). Conscious consumers are changing the rules of marketing. Are you ready? Retrieved May 14, 2010, from http://www.bbmg.com/pdfs/BBMG_Conscious_Consumer_White_Paper.pdf.

Berens, G., van Riel, C. B. M., & van Bruggen, G. H. (2005). Corporate associations and consumer product responses: The moderating role of corporate brand dominance. Journal of Marketing, 69(3), 35–48.

Berman, S. L., Wicks, A. C., Kotha, S., & Jones, T. M. (1999). Does stakeholder orientation matter? The relationship between stakeholder management models and firm financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 42(5), 488–506.

Berns, M., Townsend, A., Khayat, Z., Balagopal, B., Reeves, M., Hopkins, M., & Kruschwitz, N. (2009). The business of sustainability: findings and insights from the first annual business of sustainability survey and the global thought leaders’ research project. MIT Sloan Management Review Special Report. Retrieved May 14, 2010, from http://www.mitsmr-ezine.com./busofsustainability/2009#pg1.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Korschun, D. (2008). Stakeholder marketing: Beyond the four P’s and the customer. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 27(1), 113–116.

Biehal, G. J., & Sheinin, D. A. (2007). The influence of corporate messages on the product portfolio. Journal of Marketing, 71(2), 12–25.

Boyd, D. E., Chandy, R. K., & Cunha, M. (2010). When do chief marketing officers affect firm value? A customer power explanation. Journal of Marketing, 47(4), 1162–1176.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2006). Firm size, organizational visibility and corporate philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Business Ethics: A European Review, 15(1), 6–18.

Brenner, S. N., & Cochran, P. L. (1991). The stakeholder theory of the firm: Implications for business and society theory and research. In J. F. Mahon (Ed.), Proceedings of the international association for business and society (pp. 449–467). Utah: Sundance.

Brickson, S. L. (2007). Organizational identity orientation: The genesis of the role of the firm and distinct forms of social value. Academy of Management Review, 32, 864–888.

Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68–84.

Burke, L., Logsdon, J. M., Mitchell, W., Reiner, M., & Vogel, D. (1986). Corporate community involvement in the San Francisco Bay area. California Management Review, 28(3), 122–141.

Cappelli, P., Singh, H., Singh, J. V., & Useem, M. (2010). Leadership lessons from India. Harvard Business Review, 88(3), 90–97.

Chen, K. H., & Metcalf, R. W. (1980). The relationship between pollution control record and financial indicators revisited. Accounting Review, 55(1), 167–177.

Choi, J., & Wang, H. (2009). Stakeholder relations and the persistence of corporate financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 30(8), 895–907.

Chung, K. H., & Pruitt, S. W. (1995). A simple approximation of Tobin’s q. Financial Management, 23(3), 70–79.

Crittenden, V. L., Crittenden, W. F., Ferrell, L. K., Ferrell, O. C., & Pinney, C. C. (2011). Market-oriented sustainability: A conceptual framework and propositions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 71–85.

Daft, R. L., Sormunen, J., & Parks, D. (1988). Chief executive scanning, environmental characteristics, and company performance: An empirical study. Strategic Management Journal, 9(2), 123–139.

Dawar, N., & Pillutla, M. M. (2000). Impact of product-harm crises on brand equity: The moderating role of consumer expectations. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(2), 215–226.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65–91.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2007). Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 24(3), 221–241.

Dutta, S., Narasimhan, O., & Rajiv, S. (1999). Success in high-technology markets: Is marketing capability critical? Marketing Science, 18(4), 547–568.

Edelman Goodpurpose. (2012). Edelman goodpurpose 2012 Global Consumer Survey. Accessed May 1, 2012, from http://purpose.edelman.com/.

Ellen, P. S., Webb, D. J., & Mohr, L. A. (2006). Building corporate associations: Consumer attributions for corporate socially responsible programs. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 147–158.

Erfle, S., & McMillan, H. (1995). Media, political pressure, and the firm: The case of petroleum pricing in the late 1970’s. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 105(1), 115–134.

Evan, W., & Freeman, R. E. (1993). A stakeholder theory of the modern corporation: Kantian capitalism. In T. Beauchamp & N. Bowie (Eds.), Ethical theory and business (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Fama, E. (1970). Efficient capital markets: A review of theory and empirical work. Journal of Finance, 25(2), 383–417.

Ferrell, O. C., Gonzalez-Padron, T. L., Hult, G. T. M., & Maignan, I. (2010). From market orientation to stakeholder orientation. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 29(1), 93–96.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder theory approach. Boston, MA: Pitman.

Godfrey, P. C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 777–798.

Godfrey, P. C., Merrill, C. B., & Hansen, J. M. (2009). The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal, 30(4), 425–445.

Graves, S. B., & Waddock, S. A. (1994). Institutional owners and corporate social performance. Academy of Management Journal, 37(4), 1034–1046.

Haleblian, J., & Finkelstein, S. (1993). Top management team size, ceo dominance and firm performance: The moderating roles of environmental turbulence and discretion. Academy of Management Journal, 36(4), 844–863.

Hambrick, D. C. (1981). Environment, strategy, and power within top management teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26(2), 253–276.

Hatch, M. J., & Schultz, M. (2003). Bringing the corporation into corporate branding. European Journal of Marketing, 37(7/8), 1041–1064.

Hillman, A. J., & Keim, G. D. (2001). Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s the bottom line? Strategic Management Journal, 22(2), 125–139.

Hitt, M. A., & Ireland, R. D. (1985). Corporate distinctive competencies, strategy, industry and performance. Strategic Management Journal, 6(3), 273–293.

Hoeffler, S., Bloom, P. N., & Keller, K. L. (2010). Understanding stakeholder response to corporate citizenship initiatives: Managerial guidelines and research directions. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 29(1), 78–88.

Holt, D. B., Quelch, J. A., & Taylor, E. L. (2004). How global brands compete. Harvard Business Review, 82(9), 68–75.

Hopkins, M. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and international development: Is business the solution?. London: Earthscan.

Iyer, E. S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2011). Marketing and society: Preface to special section on volunteerism, price assurances and direct-to-consumer advertising. Journal of Business Research, 64(1), 59–60.

Jamali, D. (2008). A stakeholder approach to corporate social responsibility: A fresh perspective into theory and practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(1), 213–231.

Janney, J. J., & Gove, S. (2011). Reputation and corporate social responsibility aberrations, trends and hypocrisy: Reactions to firm choices in the stock option backdating scandal. Journal of Management Studies, 48(7), 1562–1585.

Jocz, K. E., & Quelch, J. A. (2008). An exploration of marketing’s impacts on society: A perspective linked to democracy. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 27(2), 202–206.

Joshi, R. (2012). Sustainability and B2B brands: Driving green for growth. Interbrand Online Library. Accessed May 1, 2012, from http://www.interbrand.com/Libraries/Articles/9_Sustainability_and_B2B_pdf.sflb.ashx.

Kennedy, P. (2008). Econometrics (6th ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Knox, S., & Bickerton, D. (2003). The six conventions of corporate branding. European Journal of Marketing, 37(7/8), 998–1016.

Kotchen, M. J., & Moon, J. J. (2007). Corporate social responsibility for irresponsibility. Unpublished Manuscript, University of California at Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA.

Krishnan, H. A., Tadepalli, R., & Park, D. (2009). R&D intensity, marketing intensity, and organizational performance. Journal of Management Issues, 21(2), 232–244.

Laplume, A. O., Sonar, K., & Litz, R. A. (2008). Stakeholder theory: Reviewing a theory that moves us. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1152–1189.

Lawrence, P. R., & Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Organizations and environment. Boston, MA: Harvard University.