Abstract

Academic literature recognizes that firms in different countries deal with corporate social responsibility (CSR) in different ways. Because of this, analysts presume that variations in national-institutional arrangements affect CSR practices. Literature, however, lacks specificity in determining, first, what parts of national political-economic configurations actually affect CSR practices; second, the precise aspects of CSR affected by national-institutional variables; third, how causal mechanisms between national-institutional framework variables and aspects of CSR practices work. Because of this the literature is not able to address to what extent CSR practices are affected by either global or national policies, discourses and economic pressures; and to what extent CSR evolves as either an alternative to or an extension of national-institutional arrangements. This article proposes an alternative approach that focuses on an exploration of links between disaggregated variables, which can then be the basis for imagining new national-institutional configurations affecting aspects of CSR. It illustrates this approach with an exploration of the importance of development aid policy for CSR practices in global supply chains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is the term that describes a firm’s voluntary actions to mitigate and remedy social and environmental consequences of its operation.Footnote 1 It plays an increasingly significant role in public discourse on the governance of globalization, in particular as the transnational organization of production and, consequently, the disembedding of economic action from enforced public regulation has accelerated over the last decades (MacDonald and Marshall 2010).

In the effort to explain why firms engage with CSR, and why they choose for particular types of CSR practices, the institutional environment of business plays a significant role (Campbell 2006; Crouch 2006; Matten and Moon 2008). Many authors hold that as part of this environment, national-institutional pressures are a significant drivers to variations in corporate strategies towards CSR, and varying types of self-regulation and private regulation (Christopherson and Lillie 2005; Kollman and Prakash 2002; Matten and Moon 2008; Lee 2011). In recent years, this notion has spurred analyses of the relationship between varieties in national political-economic configurations and varieties in CSR practices.

This article identifies important gaps in our understanding of the relationship between national political-economic configurations and CSR practices so far and develops proposals to help close these gaps. It will argue that the literature so far lacks specificity in three important respects, as a cumulative result of the conceptual and methodological characteristics of studies. First, because of its predominant focus on aggregate measures of national configurations, the literature is not yet able to identify what particular aspects of national economic systems affect CSR practices. Second, because aggregations are also used for CSR as a dependent variable, the literature cannot yet clearly distinguish what aspects of CSR are precisely affected in what way by variation in national-institutional environments. Third, the literature so far has difficulties in providing convincing demonstration of the causal mechanisms at work between national institutions and corporate strategies towards CSR.

Because of this, the literature so far is not able to successfully address what are arguably two key questions pertaining the relationship between CSR and the national-institutional environment: First, to what extent CSR embodies a global diffusion of business norms and practices? Second, to what extent CSR embodies a change in the institutional framework for policies regulating and coordinating the social and environmental consequences of economic activities?

More clarity with regard to these questions is also significant for professionals engaging with CSR in business and non-profit organizations, and policymakers concerned with social and environmental issues. Understanding to what extent CSR is nationally embedded, and what role different national institutions play in shaping business practices can help these professionals think more clearly about the scope of CSR in different countries, the appropriateness of specific governmental policies and about the trade-offs of different strategies to embed economic practice in norms of appropriate behaviour.

The article then suggests revisions in how to treat these questions. As a first step, it proposes to comparatively and qualitatively focus on the relationship between particular aspects that are disaggregated from the big concepts ‘CSR’ and ‘national political-economic configurations’. By doing so it seeks to establish causal links from bottom-up, instead of from top-down. Working from the bottom-up means that inductively institutional ensembles can be identified that do not have to be restricted to common comparative political economy variables, but may include aspects of the organization of civil society and specific elements of government regulatory and distributive policy. In addition, such an approach may then more easily engage with academic debates that are organized around particular dimensions of CSR practice as a dependent variable, and which do not use an elaborate understanding of national political-economic configurations, such as studies of business engagement with certification, private labour regulation, sustainability reporting and environmental management systems. This means that a more integrated understanding of the national embeddedness of different kinds of responsible business behaviour, self-regulation and private regulation can emerge. The article illustrates the approach with an exploration of the importance of European development aid policy for the variation in CSR practices in global supply chains adopted by businesses from different European countries.

This article does not intend to dismiss the work done so far on the national embeddedness of CSR practices. It aims to treat discussed studies as valuable social science contributions. Not all the works discussed suffer from all vulnerabilities mentioned here. In most of these studies, the authors also recognize that there are limits to their analytical and empirical research strategies. The point of this article, nonetheless, is that the cumulative effect of these separate takes is a set of significant gaps in our understanding. Future research should address these gaps seriously.

The article is organized as follows. First the contributions of the literature on national varieties of CSR will be discussed. Then this literature will be scrutinized for its understanding of national political-economic configurations, CSR and the connections between the two. The section that follows draws out an alternative approach to the study of the national embeddedness of responsible business behaviour and illustrates this with an empirical example. A final section reviews the implications for academic research and for policy-making.

The Debate on the National Embedding of CSR Policies So Far: Substitution Versus Extension and the Global Versus the Local

Most introductory texts to CSR acknowledge that across countries, firms are embedded in different institutional settings. Firms in different countries face different regulatory frameworks, governments, societal stakeholders, have different relationships towards owners and engage in different types of industrial association and labour–capital bargaining. Such differences may affect how firms approach the debate on CSR (for instance, Crane and Matten 2005, pp. 26–30; Van Tulder and Van der Zwart 2006, pp. 221–230). CSR as a term is of American origin, but has since the 1990s proliferated across the globe. The national differences in applying this American invention then have become a focus of empirical research.

Contemporary literature identifies a national political-economic context to CSR strategy by investigating the effect of national variation on selections of firms that occupy positions in corporate best practice rankings of CSR activities, issue sustainability reports or participate in CSR-focused business associations (Aguilera et al. 2006; Gjolberg 2009b; Jackson and Apostolakou 2010; Kang and Moon 2011; Kinderman 2009, 2011; Maignan and Ralston 2002; Middtun et al. 2006; Steen Knudsen and Brown 2011). These national varieties accordingly signify different versions of capitalism that vary with regard to such characteristics as industrial relations, corporate governance, inter-firm relations and state intervention in the economy.

On such basis, the literature offers two rival claims concerning the relationship between national institutions and aspects of CSR. The first is that firms from countries that approximate the coordinated market economy (CME) or Rhenish and Nordic models of capitalism (Soskice and Hall 2001; compare Amable 2003) will develop more extensive CSR practices in comparison to firms from other countries. Nordic, Rhenish and CME-approximating countries are characterized amongst others by institutionalized dialogue between social partners and more stringent rules in policy areas relevant to CSR, such as labour standards and environmental protection. Such institutions make it easier for firms in these countries to comply with international CSR programs and rating schemes, since what is legally required already makes them frontrunners in comparison to firms from other countries (Gjolberg 2009b; Middtun et al. 2006). In addition, these institutions also make companies more susceptible for new types of voluntary engagement in which to continue engagement with stakeholder groups and their concerns (Campbell 2007).

The rival claim is that countries approximating the liberal market economy (LME) or Anglophone model have more extensive CSR practices. These countries are characterized amongst others by a less interventionist state, individualized and adversarial capital–labour relations and liberal markets for corporate control. Demands for solidarity and regulatory activities are taken up through private instead of public routes. CSR activities then compensate for the absence of institutional solidarity and stringent public regulation (Jackson and Apostolakou 2010). In line with literature that identifies institutional changes in the political-economic configuration of Continental Europe as a move towards a LME and Anglophone model (Nölke 2008), Daniel Kinderman (2009, 2011), furthermore, proposes that CSR may be on the rise in Continental Europe precisely because conventional forms of capital–labour interaction and state intervention are in retreat there. CSR then functions as legitimation of liberal markets in the United States and the United Kingdom and as legitimation of a process of marketization elsewhere.

These rival claims find support mainly in large-N empirical analysis using inferential statistics or qualitative comparative analysis (QCA). The data used for exploration of qualities of CSR are corporate policy documents and public rankings based on such documents. Hypotheses used for the large-N analyses are mostly based on deductive reasoning or smaller case studies comparing corporate policy documents (see, for instance, Campbell 2007; Maignan and Ralston 2002; Steen Knudsen and Brown 2011).

Most of these studies in addition consider other factors that may drive variation in CSR practices. These include amongst others differences between industrial sectors (Jackson and Apostolakou 2010) and political culture (Gjolberg 2009b). Alternatively, studies emphasize how degrees of internationalization and the presence of multinational corporations may affect CSR practices in a country (Gjolberg 2009b; Steen Knudsen and Brown 2011). By doing so, they open up a second analytical debate, as to the source of variation in CSR practices across countries: Do we have variation in national versions of CSR because of global forces and the position of countries in the global economy, or because of the effect of local institutional environments? Gjolberg (2009b) in this regard finds that both local institutions and global connectedness may drive more or less extensive CSR practices, although possibly in different ways (compare Steen Knudsen and Brown 2011).

Overall, at the heart of the argument, is the interaction between national political-economic configurations, on the one hand, and measures of CSR that express degrees of extensiveness, comprehensiveness, progressiveness and advancement, on the other. And with regard to both the prevalent mechanism and the direction of causality, we are at present left with puzzles: Do more coordinative or more liberal types of national political-economic configurations advance extensive CSR practices? Or do both configurations promote CSR at specific times (Kang and Moon 2011)? And is CSR developed due to global pressures, local pressures or both?

In the next sections, these contributions will be scrutinized.

What We Do Not Yet Know About the National Embeddedness of CSR

The present literature has three limits. Based on what we have learned so far we remain predominantly uncertain about what aspects of national-institutional frameworks of business actually affect CSR practices, self-regulation and private regulation; about what aspects of CSR practices are affected; and how the causal mechanisms between the two phenomena work. These limits constrain efforts at convincingly solving the puzzles in the literature identified in previous section. In the sections below, these three different elements will be discussed in turn.

What Parts of the National-Institutional Environment Affect CSR Practices?

Most studies of the national embeddedness of CSR practices base their hypotheses on comparative political economy literature that establishes variation in national business systems, or, versions of capitalism with regard to corporate finance and governance, inter-firm relations, capital–labour relations, education and training (Soskice and Hall 2001), and state institutions and policy, financial systems and trust relations (compare Amable 2003; Becker 2008; Whitley 1999). This is a sensible starting point, since this literature provides ample inspiration for theorizing on the embedding of economic practice in national configurations. However, connecting ‘comparative capitalism’ (Jackson and Deeg 2008) to the study of CSR practices is not without its problems. This section, in particular, discusses the usage of imprecise empirical results for specified theoretical arguments; the sustaining of analytical problems of the varieties of capitalism (VoC)-approach to comparing national configurations; and the relative disregard of elements of political-economic configurations not treated in the comparative capitalism-literature.

The studies on national embeddedness of CSR so far provide arguments focusing on the replacement versus extension of certain features of the national environment by CSR practices, self-regulation or private regulation. These features include social or environmental government policy, corporate governance and capital–labour relations. In line with the notion of the complementarity of institutions, some of these arguments state that CSR practices have a particular position with regard to the combined functioning of these institutions. However, many studies use aggregate measures of varieties across national versions of capitalisms, rather than focusing on specific elements, or the combination of elements that may affect CSR practices. Measures used include countries as units of analysis reflecting typical versions of capitalism, or tax rates and investment laws which are proxies for the elaborateness or the regulatory character of the (welfare) state (Kinderman 2009; Jackson and Apostolakou 2010). The likely relationship between national political-economic configurations and CSR practices are thus relatively specifically theorized. But national institutions are not always sufficiently operationalized to show the proposed relationship empirically at work (for an exception see Gjolberg 2009b). We should, therefore, be careful about not creating a mismatch between the specificity of data and the level of generality of the theory used.

The most cited study that compares national versions of capitalism is the VoC volume by Soskice and Hall (2001). It is, therefore, the most likely source of emulation by scholars investigating national variety in CSR (see, for instance, Jackson and Apostolakou 2010; Kang and Moon 2011; Middtun et al. 2006). Studies may use Soskice and Hall’s distinction between LMEs and CMEs in selecting and analyzing cases of national-institutional variety. Alternatively, they may include an extra ideal type of state-led market economies (SLMEs), a category that emphasizes the importance of state institutions (relative to corporatist arrangements or market forces) in socio-economic governance. Because of this, studies of CSR practices are also in danger of inheriting and sustaining some of the shortcomings of the VoC-approach that have been outlined in recent years (Becker 2008; Crouch 2005; Jackson and Deeg 2008).

The main criticism concerns its static depiction of political-economic institutions in temporal and geographic terms. Because of its insistence that national-institutional variation will prevail in times of globalization, the VoC-approach is a difficult starting ground to theorize national-institutional change. And because CSR practices may embody or advance such change, the fit with regard to the debate on the national embeddedness of CSR is in particular problematic (see also Kinderman 2009). Much of this stasis is related to the fact that VoC-analysts conflate country cases with national capitalist ideal types, instead of constructing ideal types of capitalist diversity and describing national cases as more or less approximating such ideal types, based on empirical research (Becker 2008). This does not only mean that institutional change becomes difficult to describe but also creates the problem of identifying country cases that are empirically in between the LME and the CME, or in between LME and CME and the newly proposed SLME models in terms of their institutional characteristics (Kang and Moon 2011). The study of national embeddedness of CSR then is in danger of falling prey to the crude dichotomy of two or three models, in both case selection and causal inference. Or, alternatively, treating changes in a country as changes in a model, rather than deviation from it. Finally, critics lament that the selection of key factors that make up the categories of VoC are not sufficient to describe the appropriate variation; most of all, approaches adopting VoC are in danger of missing out on variation in state policy (Becker 2008; Crouch 2005; cf. Amable 2003). This may be an important variable affecting CSR policy.

In establishing variations amongst countries, comparative capitalist research assumes the importance of the inter-play of different kinds of national institutions. These ensembles have so far predominantly been used in the literature to explain national indicators of economic performance. Jackson and Deeg (2008, p. 683), for instance, summarize the literature’s interest in the effects of national complementarity of national institutions on innovation, production strategies and distributional outcomes.

As said, the ensembles of institutions identified in this literature are also used to explain variation in CSR policies. The explanatory value of these particular ensembles as representative of variation within national economic systems for CSR issues is, however, not self-evident. To be sure, the relationship between the processes that drive national varieties in innovation, production and distribution, on the one hand, and CSR, on the other, is worth exploring. There is a connection between these indicators of economic performance and the kind of things that firms do with regard to their ethical agenda. CSR is after all about managing negative externalities of mostly production and for many industries CSR concerns may be solved by way of innovation, in particular, with regard to energy and waste.

But it is questionable whether we should prioritize specifically these ensembles in an investigation of CSR. CSR, after all, so far is not integral to economic innovation, production and different types of economic distribution, at least not organizationally speaking. Studies show that CSR strategies too often lead a marginalized existence in the corporate organization (Mamic 2004; Crane 2000). We should, therefore, take into account that different political-economic national institutions may affect CSR. The literature on the emergence and adoption of specific CSR practices, for instance, points us to the role that consumers, NGOs and discourses on sustainability play (Micheletti 2003; Sasser et al. 2006). The power and significance of these factors are of course also affected by the character and quality of other national political-economic institutions. In other words, concentrating on VoC and broader comparative capitalism-literature may result in neglect of those variables not inherent in the comparative capitalisms-models, which may, however, play a significant role in explaining national variation with regard to CSR issues. And institutions that establish certain results in one sphere of business activity should, therefore, not be too hastily considered to also have the most significant effect in other spheres.Footnote 2

What Part of CSR is Affected by National-Institutional Environments?

This section will argue that because recent studies of the national embeddedness of CSR use aggregate conceptions of CSR as a dependent variable, much remains unclear about what aspects of CSR practices are actually affected by national political-economic configurations. This is because of the conflation of different aspects of policy-making, unclear division of geographic scope, and lack of preciseness with regard to corporate engagement with different CSR issue areas.

Most studies so far gauge CSR practices based on (a combination of) the following data: first, corporate policy document analysis; second, data sets from existing CSR ranking tools which are based on corporate policy document analysis; third, corporate participation in business associations geared towards CSR goals; fourth, corporate participation in certification programs and private regulatory organizations.

Jackson and Apostolakou (2010), for instance, analyse companies participating in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. Gjolberg (2009a, b) uses a mixed weighing of membership in business associations, environmental process management certification with sustainability indexes and business toplists. The obvious disadvantage of such indicators is that the population of companies analysed is likely to be leaning towards larger, stock-listed organizations. But we could argue that as a first step into the analysis of national institutions and their effects on CSR practices we are interested in the ‘big fish’, because of their prominent place in debates about fair globalization and their possible impact on social and environmental issues.

Most of the studies take the pragmatic approach to defining what is meant by CSR: the authors leave it to the indicators developed by businesses, analysts and stakeholders to determine what falls inside and outside of the scope of the concept, in terms of both policy tools and issues. We might, however, also be interested to disaggregate some of the aspects of CSR practices because of the different political and managerial implications they have. The classic distinction in analysing voluntary responsible business behaviour in the business ethics literature is, for instance, between CSR (signifying a corporation’s stated obligations and accountability to society), responsiveness (the activities that follow from this) and performance (the results of these activities, for discussion see Crane and Matten, 2005, pp. 41–49). The measure of ‘CSR practices’ used in the literature on the national embedding of CSR tends to conflate the first two. This means that based on current research we do not know to what extent national variation in political-economic configuration affects the scope of obligations taken on by firms, and to what extent it affects the precise activities that are developed to put these obligations into practice.

If we use more specific distinctions, inspired by policy-making literature (see, for instance, Parsons 1995) we can identify seven relevant dimensions of corporate engagement with CSR in a country: quality of standards adopted (for instance, specificity and elaborateness of standards with regard to working conditions, environmental damage); policies adopted to implement and monitor these standards (in terms of elaborateness, stringency, etc.); scope of policies (governing the corporate organization, the whole or parts of the supply chain, with a national, regional or global reach); issues addressed (environmental, social, human rights-related, etc.); quality of reporting on performance (in terms of elaborateness and transparency); degree of outside verification of results (indicated by membership in associations, voluntary programs, certification schemes) and scope of uptake of policies (by only a few or by a majority of industry in a given country).

All dimensions have something significant to say about the quality of a country’s corporate efforts towards CSR. Yet these dimensions may in different ways be related to national-institutional environments. The present literature either uses yardsticks of CSR that mix these different elements together or uses one of the aspects identified above as a proxy for quality of CSR as a whole. The former may result in imprecise measurement of relationships between national environments and CSR practices. The latter may result in unspecific statements about the variation identified. Gjolberg’s work (2009a, b) is an example of a mixed measurement of CSR practices. On the basis of her work, we see that firms from Nordic countries may be more amenable to apply high standards and/or report transparently on performance and/or have their performance reviewed by third parties and/or apply CSR across the supply chain, and so on. Meanwhile, the degree of a firm’s engagement with transparent reporting, stringent standards of behaviour and responsibility with supplier companies all may interact in different ways with different aspects of Nordic political-economic institutions. What is, for instance, common practice regarding non-CSR business reporting requirements in a country might have some impact on CSR reporting practices of businesses, as one specific element of CSR practices. It may, however, affect other elements to a lesser degree, such as the degree to which Nordic companies join programs that verify their commitment to CSR standards in supply chains.

Kinderman’s work (2009) is an example of a study using a singular proxy for CSR practices. It argues for a ‘substitute’ effect of CSR and national regulation, while in effect it measures national variation in business propensity to organize in CSR-focused business associations. But, rather than an integral aspect of CSR, this willingness of firms to organize on CSR may be hypothesized to be an effect of national variation in patterns of industrial association, or, put simply, national variation in firms’ willingness to act collectively in the first place, as Kinderman himself recognizes. The relationship with the argument on substitution of conventional forms of social and environmental bargaining and regulation is, therefore, not yet clear. As was established in the previous section, we do not know whether this element was the most important driver to variation, since aggregate variables of national institutions were used to study variety across countries. The proxy, furthermore, does not tell us about national variation in what business associations demand from their members in terms of commitment to standards, performance, reporting and so on. This variation in itself may be relevant for identifying national variation in CSR practices. If the French national association is more lenient in terms of required participant commitment in comparison to the Belgian one, we may actually be measuring a difference in preference due to variation in stringency of CSR standards, rather than differences that can be explained through national-institutional variety (Prakash and Potoski 2007).

Furthermore, the measurements of CSR used do not distinguish between business practices addressing CSR issues at home or abroad (see also Steen Knudsen and Brown 2011). This is a significant distinction since we may easily expect a close interaction between nationally focused business policies and existing elements of a national political-economic configuration identified in these studies, tailored to issues belonging to the CSR agenda. This interaction may then lead us to hypothesize about the ‘mirroring’ or ‘substituting’ relationship between national-institutional frameworks and CSR practices. Policies with regard to anti-discrimination or waste management at home may, for instance, be attuned to national discussions, routines and regulations with regard to these issues. For issues that relate to business activities abroad, through export, import or Foreign Direct Investment channels, the relationship between the national political-economic configuration as identified so far by these studies and CSR practices is probably less clear-cut.

Similarly, the measurements of CSR used in the literature so far do not disentangle the extent of business commitment to social or environmental or broader human rights standards. This while their theories propose interactions between CSR practices and national institutions that may be more suited for some of these categories of standards than for others. For instance, the theses on mirroring or substituting of national-institutional environments work really well with regard to the issue of social standards. There, conventional corporatist arrangements structuring interactions between representatives of labour and capital may spill over into or be traded-off for CSR stakeholder dialogue arrangements. With regard to environmental and human rights standards, different regulatory constellations interact with CSR. The link with corporatism is much less clear-cut here, since these issues do not conventionally form part of corporatist institutional interaction. Using aggregate measures of CSR, it remains uncertain how these different constellations may affect business engagement with these issues. And theories deduced from corporatism studies seem to make less sense in approaching the non-labour aspects of the CSR agenda.

How Do the National-Institutional Environment and CSR Affect Each Other?

As we have seen, the study of national determinants of CSR strategies has led to a controversy regarding the impact of national institutions on corporate activities. It is undecided whether certain institutional features such as strength of corporatist tradition foster or hamper corporate engagement with CSR. It could very well be that this controversy stems from usage of different indicators of CSR practices, as discussed above. This would mean that the substitution thesis could hold for a specific element of CSR practices, while the extension argument holds for a different one. Alternatively, it may be that different populations of organizations have been sampled in the studies discussed. In this case, the common advice in methodological literature is to increase the amount of observations to more clearly establish empirical patterns and derive appropriate conclusions (King et al. 1994).

Previous sections have shown that there may be ground to base these new observations on alternative operationalizations of the key variables, an issue that we return to below. Meanwhile, we may also wonder whether the data and methods used so far allow us to illuminate the causal mechanisms we are looking for. In terms of the data, the analysis relies mostly on corporate self-presentation and rankings of self-presentation by third parties. This means that the analysis is based on comparison of static snapshots. Using these data sources has obvious advantages in terms of the availability and reliability of data. Most of the reports on which analyses are based can be freely reviewed by researchers. The drawback in terms of our understanding of the national embeddedness of CSR is that studies hardly provide data on the process of strategizing within firms and the observable interactions between components of the national-institutional framework and business activities.Footnote 3

A second drawback is that most data used do not allow us to distinguish between, on the one hand, CSR practices, self-regulation or private regulatory participation that follows from legal requirements and, on the other, practices that may be driven by other kinds of national-institutional pressures. This is obviously an interesting distinction to pull apart if we consider that, first, most definitions of CSR stress the voluntary nature of business engagement with social and environmental standards. Is CSR through legal requirements then still CSR? Second, our interest in the relationship between national political-economic configurations and CSR require us to specify the character of the relationship between the two as best as possible. We should, therefore, be clear about what we are measuring to grasp the mechanism at work. Ideally, we, therefore, need to work with data that separate different types of interactions between CSR practices and national institutions.

In terms of method, most studies apply QCA or inferential statistics to large case selections of firms or industries in countries (for an exception using a few exemplary case studies, see Kinderman 2009; Steen Knudsen and Brown 2011). While some would hold that such large-N methods are sufficient to demonstrate the functioning of a causal mechanism, social science methodologists stress two requirements for successful identification of a mechanism: first, the existence of a general model explaining a wide variety of outcomes; and second, observation of a process running from a cause to an effect we are interested in (Gerring 2001; Marini and Singer 1988). Through its rooting in comparative political economy, the literature can amply provide the former but it currently scarcely provides the latter.Footnote 4

While one may have issues with the methodological position as generally advanced here, it is clear that with regard to the theoretical debate on CSR and national institutions, analyses so far lead to ambiguous conclusions. We are uncertain about both the direction of causality and whether the assumed independent variable stands in a positive or negative relationship to the assumed dependent variable. We may at least conclude from this that adding alternative methods to those presently applied will be useful. Not only extended application but also diversification of both methods and data may help to overcome the puzzle that the present literature leaves us.

An Alternative Approach: Disaggregation, Causal Links and New Ensembles

We have so far established that to learn about the interaction between national political-economic configurations and CSR practices, we run into limits if we rely on aggregate measures of both, and on large-N methods with static snapshot data to establish their interaction. Below, an alternative direction for research will be outlined, focusing on the disaggregation of concepts, process-tracing, induction and openness towards other literatures. This route may complement the research done so far and increase our understanding of the national embeddedness of CSR. By advocating such direction, this article basically chimes in with those comparative political economy approaches that promote an inductive, empirically informed construction of concepts and typologies across country cases, and sensitivity to complexity to study national diversity and institutional change in modern-day capitalism (Amable 2003; Becker 2008; Crouch 2005).

The first way to advance the study of the national embeddedness of CSR is to use smaller and more specific measures of both national political-economic configurations and CSR practices. The empirical focus of the study can then be specified depending on an interest in particular aspects of a national-institutional environment as an independent variable, or particular CSR practices as a dependent variable.

Starting with the former, theories so far assume a relationship between, for instance, stricter environmental regulation, generous welfare policies and well-established corporatist arrangements, on the one hand, and CSR practices, on the other. Studies can then use measures of these variables and probe their effects (see, for instance, Gjolberg 2009b). Moreover, particular CSR practices can be identified that may to a greater or smaller degree be affected by such variables. We may select several, including particular issue fields, the participation of firms in organizations monitoring actions in supply chains, quality of reporting, and so on. We can then see more clearly whether there is a relationship with particular aspects of a national political-economic configuration of interest to us and establish how the two may affect each other.

If we are principally interested in particularly CSR practices and want to learn how national embeddedness affects them, we can conversely select for those aspects. Theoretically, we may, for instance, expect that there is a national embedded character to CSR reporting by firms or the emergence of business–NGO collaborations with regard to certifying social and environmental requirements of production. We may then study which parts of the national-institutional environment affect such practices. Important here is that the factors of possible influence may extend the categories identified by the comparative capitalism-literature. This means that care should be taken to identify appropriate categories of variations.

Methodologically, it is, therefore, crucial that the research design is sensitive to inductive reasoning. This would mean, first, that smaller qualitative case study set-ups would be most appropriate in the first phase of investigation. Second, in line with the notion that for the establishment of causal mechanisms we need both a general theoretical framework and an idea of how the relationship between cause and effect empirically functions, it is important to apply process-tracing (for discussion see George and Bennett 2004). This means that empirical information needs to be gathered that establishes as precisely as possible the interactions between variables, ideally across time and space.

In terms of data, this implies a focus on interview data with representatives of firms and those organizations surrounding them, in combination with policy document analysis, potentially participant observation during professional gatherings, and socio-economic statistics concerning firms, sectors and countries.

Such advice may cause some researchers to lament the implicit preference contained in using qualitative case study designs and closer-to-date source-research methods. Indeed, there are strong advantages to using these in the first phases. But, importantly, there is no objection to using the results of such studies for larger QCA and inferential-statistical purposes.

The advantage of such a set-up is that it, first, becomes possible to confirm or refute assumptions about the effect that different national-institutional environments have on particular aspects of CSR strategies and policies. Second, it may, based on results, be possible to propose different ensembles of national institutions that affect CSR policies than the ones currently identified. Accordingly, different kinds of institutional complementarity of CSR practices can be described. These can then be tested for a larger population of cases using inferential statistics or QCA.

Finding possible new variables that may be included in such ensembles does not have to be a chance-encounter affair. Using disaggregated measures of CSR practices and national political-economic configurations has as an advantage that we can more easily relate to the literature that describes specific aspects of these concepts but has so far remained outside or at the margin of discussions in the studies of the national embeddedness of CSR.

With regard to national political-economic configurations we can build on the literature that comparatively describes institutional features plausibly relevant to CSR practices. The literature on government policies focusing on CSR provides a lot of clues on what kinds of pressures may be exercised on industries in different countries (Albareda et al, 2007; Knopf et al. 2011; Steuer 2010). We can also think of comparative studies probing government external economic policy, such as trade agreements or aid policies, which may intertwine with the international scope of CSR practices. Similarly, comparative studies of consumer attitudes may go some way in providing information on differences across countries (Lee et al. 2011; Clarke 2008). And strength of organization of civil society groups can also be gauged for different countries (Kriesi et al. 1992).

With regard to different CSR practices, we can build on studies that aim to shed light on specific aspects of CSR, and which then in the process develop causal inferences regarding national-institutional variables. Work on environmental management systems, for instance, shows the positive influence that practical government and business association assistance has on adoption of environmental requirements by companies (Kollman and Prakash 2002). In a similar vein, studies show the significance of government procurement in advancing certain models of sustainability certification (Auld et al. 2008). And others propose that national variation in discourses and practices of consumer sovereignty and experiences with accounting standards may explain differences in business preferences for organizing multi-stakeholder initiatives and reporting on CSR performance (Hughes et al. 2007).

Such a set-up may thus facilitate theoretical openness, because it eases integration of other perspectives on corporate behaviour outside of the realm of the academic sub-discipline of comparative political economy. Using the proposed set-up, it will become easier to build links with approaches favoring other independent institutional variables for corporate action, that stem from other academic traditions, such as policy studies, organization theory, social movement research and economic geography. Similarly, it facilitates integration with dependent-variable-focused studies of CSR strategies that already take into account national determinants of corporate action.

As a first step, we can design hypotheses, to probe the relevance of the presented approach.

This article will illustrate how such hypothesizing may work and what insights can be drawn from it, in terms of the added value to our understanding of the embeddedness of responsible business practice. The example focuses on development policy and its possible impact on different aspects of the private regulation of social standards in global supply chains of Western European firms.

CSR, Development Policy and State Strategies in the Global Economy

The case in this section shows that we can hypothesize about new ensembles of national institutions affecting CSR and thereby create more insight into the debate on the global or local dimension of CSR and its substituting or extending quality vis-à-vis national institutions.

What is striking about the literature on national institutions and their interaction with CSR practices, is that it so far focuses mostly on national institutions that affect domestic economic conditions. This while, as noted above, CSR practices to a significant extent deal with cross-border issues (see also Steen Knudsen and Brown 2011). Moreover, academic literature notes cross-national variation in the ways that national institutions govern cross-border economic issues (Palan and Abbott 1996). An empirically fruitful starting point for investigation of this variation of external economic policies is development aid, and in particular its relationship to private regulation of global supply chains. Focus is on variation between Western European countries. The analysis is based on a combination of semi-structured interviews (N = 20) with representatives of businesses, civil society organizations and development ministries and agencies in the Netherlands, Germany, the UK and Belgium, together with policy document analysis and secondary literature review, performed between 2006 and 2011.

Within the field of private regulation of social standards in global supply chains, we find interesting variation across these countries that may or may not relate to development aid interventions. We find, for instance, that in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom many different private regulatory organizations have come into existence that focus on sustainability issues in global supply chains, such as Fair Wear Foundation, Ethical Trading Initiative, Max Havelaar (precursor of Fair Trade), Responsible Jewellery Council and Better Sugar Cane Initiative. Comparatively, Germany and France, while significant economies and importers, have seen less private regulatory development activities. Moreover, numerically, the participation of, for instance, French businesses has been lower in private regulatory organizations than the participation of businesses from Denmark or Austria. This while France has a much larger economy than these countries. And while in Germany the uptake of private regulation of social standards has been higher than in France, fewer German businesses participate in multi-stakeholder initiatives, compared to Dutch and British businesses.Footnote 5

Governmental development agencies and development ministries are in many ways involved with the development of CSR practices in several countries. Especially in Western Europe, agencies and ministries have been involved in bringing together businesses, unions and NGOs to facilitate voluntary business activities with a human rights, social and environmental dimension. We can distinguish different interventions by developmental ministries and agencies in the advance of CSR practices in global supply chains.

First, most directly, development agencies have initiated and financed roundtables that were precursors to private regulatory organizations focusing on social and sustainable development issues of European multinationals. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the Labour administration helped create the Ethical Trading Initiative, an organization governed by NGOs, unions and businesses aiming to regulate labour conditions in the clothing and food supply chains of mass retailers. In Norway, similarly, the ministry assisted in the creation of Norwegian Ethical Trading Initiative. The Dutch development ministry contributed to negotiations that led to the Fair Wear Foundation, focused on working conditions in the clothing industry.

Second, development agencies have concerned themselves with programs that were aimed at making the policies of private regulatory organizations smarter and better aimed at the interests of local stakeholders in developing countries. The German development agency Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ), for instance, engaged in a program with the Business Social Compliance Initiative, an organization aiming to regulate social and environmental conditions of production in the supply chains of continental European retailers. GTZ offered assistance in creating local stakeholder roundtables that gave input into the efforts of business members of this initiative. It thereby stimulated insight into the opportunities and constraints of contemporary private regulation for various parties, including local government, trade unions and supplier companies.

Third, development agencies also invest in capacity building for local producers in developing countries, helping them to be more effective at complying with private regulations required by their buyers. In this sense, development agencies assist European businesses towards compliance with private regulatory requirements in their supply chains, through support of their suppliers. An example of this is GTZ’s successor Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), which has performed capacity building in its Common Code for the Coffee Community program, a private regulatory organization supported by large coffee roasters.

Fourth, development agencies create policies to harmonize and scale up existing private regulatory approaches and CSR practices. This intervention is based on the recognition that in many supply chains, businesses pursue different CSR practices, and engage with different private regulations. Confusion, regulatory overlap and contradictory implementation can ensue, harming the effectiveness of these interventions (Fransen 2012). The Dutch development ministry has, for instance, financed the Dutch Sustainable Trade Initiative (IDH, Initiatief Duurzame Handel). IDH focuses on social and environmental conditions in supply chains in various sectors. It finances cooperation between businesses, to establish two things: first, increased harmonization of CSR approaches in sectors, towards a best practice; second, increased engagement with CSR practices and private regulatory efforts in sectors. Businesses engaging with these efforts applaud the role of development ministries and agencies:

It is good that government acts to bring business parties together. The range of cooperating parties is bigger and there is more willingness to cooperate. It is also important to learn from the expertise offered, next to the knowledge we can bring to the table ourselves (Interview Dutch Coffee Roaster Representative)

Fifth, development agencies indirectly contribute to pressure on businesses to adopt CSR practices. In many European countries, development ministries finance civil society organizations that campaign for social and environmental justice in the supply chains of businesses. Labour activist campaigns like the Clean Clothes Campaign, developmental NGOs like Oxfam, and also solidarity centres of trade unions depend substantially on government funding for their activities. For many of these organizations, campaigns focused on supply chains of, for instance, the electronics industry, cocoa and wood products are a part of the project funding requests submitted to development ministries. In this sense, countries like Belgium, the UK and the Netherlands contribute to the power of civil society actors to raise criticism of business practices beyond borders. This is not always to the liking of businesses themselves:

I often wonder why government would support such radicals, with their half-truths about my supply chain. And I have asked my contacts within government about ways to cut their subsidies, since I think they create more problems than solutions (Interview Dutch Retail Firm Representative)

Empirically, we thus see that development ministries and government agencies intervene in CSR practices with the aim of creating private regulations, influencing the character of private regulations, increasing the uptake of private regulatory organizations and CSR practices in the supply chain, harmonizing various CSR approaches and raising societal pressure on businesses to act responsibly in their supply chains. We may, therefore, hypothesize that the existence of such interventions matters for CSR practices.

Next, we should then question whether the degree to which development agencies and ministries intervene in CSR practices may lead to some of the variation in CSR practices across countries just mentioned. Here, we can look at different sources of variation in development policies across countries, drawing on insights from development studies. First, variation may stem from the relative size of the development aid budget. Governments spending more on development aid may then affect international CSR practices more than those that spend less. Or governments spending less on development aid may have more international CSR practices as an alternative to governmental development policies. It is noteworthy here that some of the relative big spenders in development budget (UK, the Netherlands) are prominent interveners in CSR practices. This would point to an extending relationship of the national institution of development assistance to the CSR practice of private regulation of social standards in global supply chains—not to a substituting relationship.

Second, variation may occur because of variations in substantial focus of the policies. For instance, more or less predominant political ideologies may affect views on what constitutes appropriate development aid. Especially, the predominance of liberalism in shaping governmental policy may be a higher or lower degree encourage market-driven perspectives on sustainable development, which may put the contribution of companies in donor and recipient countries centre stage in governmental development policy (for a discussion of marketized development aid, see Koch et al. 2007). One respondent, for instance, notes that

With the liberals in government, we know that our plans have to conform with a perspective focused on the benefits of market transactions and entrepreneurship. Projects focused on sustainability in supply chains that assist businesses in Europe are a perfect fit for that matter (German Development Agency Representative)

It is here, for instance, that we may hypothesize about the lower degree of French development aid engagement with CSR practices and private regulation. Could this be because of a more ‘statist’ perspective on development aid?

Next to asking whether more or less engagement of development ministries and agencies with CSR practices across countries may affect varieties in these CSR practices, we should also ask whether these interventions may be more or less effective across countries. This may be due to enabling or constraining conditions in these countries that affect the success of development policies. This brings us to a broader configurational understanding of development policy.

Analytically, this makes sense, because the shape of governmental development policy towards CSR probably co-evolves and interacts with other national-institutional factors that are focused on the global economy. Development policy often reflects a country’s prevailing trade partners in the Global South. Moreover, these trade relations often go back to colonial ties (Slater and Bell 2002). Or, alternatively, they may be catered to what countries consider their national industries’ particular strengths (Berthelemy 2006). Development policy can then increase trade, and strengthen the position of businesses in donor countries, by raising demand for products in recipient countries, or the opportunities for investment in such countries. These trade relations also affect trade policy and economic policies, as government programs may promote businesses to invest or trade with these countries. And they are mirrored in foreign policy towards these countries, on issues such as human rights, peacekeeping, position-taking within international organizations and so on. Here, the benefits of development assistance and investment programs can be made conditional on or used as leverage points for aligning with foreign policy goals.

Using these insights, we can identify an ensemble of the following institutional factors affecting CSR practices. Development assistance mirrors longer term emphases in a government’s foreign policy (for the example of Sweden, see Gjolberg 2010); the presence or the absence of multinational corporations with activities in developing countries, or sustained trade relations between European lead firms and developing country suppliers, may or may not stimulate public–private debate on sustainable development in a country; governmental development budget may also be invested in projects of civil society organizations, which may use their resources to develop awareness campaigns on human rights, labour standards and the environment that target national industries.

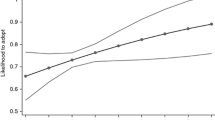

From this, we can inductively build an ensemble of national institutions that in combination address global issues, see Fig. 1. CSR practices with an international scope probably belong to such an ensemble, but are for analytical purposes depicted as separate yet inter-related.

Such ensemble will inevitably vary across countries. Once again focusing on the issue of private regulation in the supply chains of European businesses, we, for instance, note that France and Germany have less strong civil society organizations pressuring businesses than the UK and the Netherlands (Fransen 2012). French and German campaigning groups have less personnel and smaller budget than their counterparts in these countries. In the case of France, this may be a further explanation for the lower uptake of private regulation of sustainability standards in supply chains, given how local stakeholders cannot provide much societal pressure on companies to adopt CSR practices. In the case of Germany, this leads us to hypothesize, first, about why few German private regulatory organizations exist, given how civil society organizations are often instrumental in developing these organizations. Second, we can hypothesize why the German participation in business-controlled private regulation is much higher than in multi-stakeholder-governed private regulatory organizations that include civil society organizations in governance. This could be because local pressure for multi-stakeholder-governed regulation is not forceful.

This ensemble of development policy, foreign policy, transnational economic flows and civil society organization speaks directly to the discussion of whether CSR practices are shaped by global or national variables. National-institutional ensembles do not only affect domestic conditions. Nor is their only position in the causal relationship with global forces that of a dependent variable. In particular, governmental institutions directly shape economic globalization in terms of trade, the organization of production, financial flows and transnational ties of solidarity. The CSR practices that deal with the externalities of global economic activity similarly may co-variate. In other words, a country’s position in the world economy and the way its domestic institutions manage globalization may affect CSR practices of businesses in that country. Differences in such positions and the management of globalization may stimulate differences in CSR practices. Such a hypothesis transcends the global–local distinction identified in the literature on the national embeddedness of CSR.

What is more, the ensemble may also give a twist to the other debate regarding the embeddedness of responsible business practices, focused on the extending or substituting quality of CSR practices to national institutions. For within the development assistance professional community it is currently an open question whether CSR practices might not be an alternative to conventional government-to-government-assistance programmes, and be an aspect of a trend towards marketized aid (Koch et al. 2007). Within this discourse, question is also whether ‘trade is better than aid’, in other words, whether developing countries are benefiting more from how European governments shape their trade relations than from their development programmes. Also with regard to outward-focused national institutions of socio-economic governance, CSR practices then figure in discussion of what should be the role of government, and what should be the role of markets in providing desirable outcomes. If development agencies trade in funding for direct aid in favour of international CSR-focused programs, the relationship between CSR and development policy may be one of substitutions. And if we follow Kinderman’s reasoning (2009), we can also hypothesize that a focus on CSR practices can serve as a legitimation for governments of lessening development assistance budgets in favour of programs encouraging business investments in developing countries. If, however, governments with stable and sizable development assistance funds stimulate a lot of CSR practices, the relationship may be one of extensions.

This section has merely explored possible causal connections, based on empirical inferences, and further systematic study should more clearly establish the significance of these connections. Arguably this ensemble of outward-looking national institutions, furthermore, does not give an exhaustive range of possible explanations about variation in national positions with regard to the private regulation of social standards in global supply chains. There are significant possible relationships to variables identified in the comparative political economy literature. With regard to France, for instance, lower emphasis of development aid policies on CSR practices, and less civil society campaigns, match a more state-focused socio-economic model, approximate to the SLME ideal type of VoC (Kang and Moon 2011). And in Germany, less civil society organization campaigning strength on global solidarity issues may be the flipside of a stronger corporatist tradition of bargaining about socio-economic issues pertinent to the domestic economy. Further research may give more insight into the inter-play between these domestic-focused and outward-focused institutional characteristics.

The point of this empirical exercise has, therefore, not been to show that comparative political-economic explanations of variation in CSR practices across countries are wrong, and that focus should shift to other variables altogether. Rather, the aim has been to show that opening up the analysis to possible alternative explanations can lead to significant insights that we lose if we restrict ourselves merely to the categories of variables set by comparative political economy. Second, this section has illustrated how disaggregating specific aspect of CSR practices, and investigating its specific relationship to particular national institutions, enriches our understanding of the embeddedness of responsible business practices. This may free us from too rigid understandings of national-institutional ensembles having a complementary effect on CSR.

Conclusion

This article has argued that the literature on the national embeddedness of CSR is so far not able to show how national-institutional environments affect CSR practices. It demonstrates that a lack of specificity in measuring both CSR practices and national political-economic configurations, and larger-N leaning analyses based on documentation offering static policy information can only do so much to enlighten us regarding the relationship between CSR practices and national institutions. Table 1 summarizes key gaps in our understanding and the proposals to help fill these gaps.

Academically, this article, therefore, promotes empirical analyses of the national embeddedness of CSR practices that disaggregate both measures of national institutions and CSR practices. Such studies would use inductive reasoning and process-tracing with multiple data sources and closer-to-data methods in the first phase of the research design. Through such efforts, new ensembles of institutions affecting CSR practices can be proposed and tested, and integration of academic perspectives on CSR practices can be facilitated. The article has used an exploration of the relationship between development aid policies across Western European countries and CSR practices focusing on global supply chains to illuminate the potential of building new ensembles from disaggregated variables. This example in particular shows how re-focusing analysis on variables beyond the comparative political economy-category may shed a new light on debates about CSR’s national and international aspects.

Countless other studies of this kind may be envisioned. Such efforts may more specifically hypothesize on mechanisms between aspects of national political-economic configurations and elements of CSR practices. Moreover, studies may develop ideas about the scope conditions of such mechanisms, establishing for which national institutions and which aspect of CSR practices mechanisms may be more or less likely to work in the expected manner.

Once again, it is important to stress that this research strategy is expected to aid further research in the sense of enriching the cumulative level of research output by the community of scholars interested in the national embeddedness of CSR. This is not an argument against specific scholars that concentrate exclusively on large-N analyses, or on static snapshot data. Rather, the idea is that these scholars in their research would use the propositions from process-focused analyses as a starting ground, encouraging optimal cross-fertilization between research efforts and their individual results.

Using proposed research strategy is likely to lead to more convincing answers to the questions of how global and national forces coincide in the shaping of CSR practices; and whether CSR practices stand in an extending or substituting relation to existing arrangements regarding social and environmental policy, and institutionalized labour–capital bargaining

From a policy-making perspective, more clarity regarding these questions also aids the work of business, union, NGO and governmental representatives. In particular, four potential insights may inform understandings of how national institutions and business practices relate. First, studies may show to what extent policies on the national level work as opportunities or constraints to CSR, and inform discussion within and across for-profit and non-profit organizations on how favourable specific governmental policies are, given their effect on business practice. Second, studies can illuminate how CSR in combination with other national arrangements may lead to more or less beneficial interactions between public and private institutions in the shaping of social and environmental outcomes. Third, research results can gauge the possible limits of a spread of particular CSR practices in geographic terms, and help managers to evaluate to what extent their commitment to CSR is likely to be matched by others across borders. Fourth, academic insights in these matters may inform political thinking about the trade-offs of different strategies to embed economic practice in norms of appropriate behaviour. Professionals concerned with social and environmental policy can then consider to what extent their efforts towards stimulating one institutional form of regulating economic practices does or does not affect other institutional forms.

What is more, the inductive approach proposed as a first step to remedying the gaps in the literature may actually facilitate cross-fertilization with practitioners. As this phase would shy away from generalized notions of national embeddedness and CSR, it is likely to result in grounded insights about particular issues and patterns in particular countries. Professionals engaging with these issues in these countries may, therefore, more easily benefit from these studies.

Notes

This description paraphrases the European Commission’s definition of CSR, which is: ‘a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis.’ See http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sustainable-business/corporate-social-responsibility/index_en.htm, accessed 15 April 2011.

Gjolberg (2009b) remedies this by also looking at general proxies for amongst others political culture.

Witt and Redding (2011) perform interviews with business representatives to gauge CSR across countries, but their questions focus on respondent’s values and preferences, not on strategic processes.

We share this point with Kang and Moon (2011) who offer an interesting analysis of developments with regard to variation across countries of corporate governance models and CSR. However, their analysis is based on discussion of developments in both, using secondary analysis, rather than empirically revealing the connections between both.

Own research, April 2012, based on measurement of business participation in private regulatory organizations using policy documentation of the websites of the Better Sugar Cane Initiative, Business Social Compliance Initiative, Common Code for the Coffee Community, Electronics Industry Citizenship Coalition, the Ethical Trading Initiative(s) in the UK and Scandinavia, Fair Labor Association, Fair Wear Foundation, Initiative Clause Sociale, Made-By, Responsible Jewellery Council, Social Accountability International’s Corporate Involvement Program.

Abbreviations

- CME:

-

Coordinated market economy

- CSR:

-

Corporate social responsibility

- GIZ:

-

Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit

- GTZ:

-

Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit

- IDH:

-

Initiatief Duurzame Handel

- LME:

-

Liberal market economy

- SLME:

-

State-led market economy

- QCA:

-

Qualitative comparative analysis

- VoC:

-

Varieties of capitalism

References

Aguilera, R. V., Williams, C. A., Conley, J. M., & Rupp, E. D. (2006). Corporate governance and social responsibility: A comparative analysis of the UK and the US. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 14(3), 147–158.

Albareda, L., Lozano, J. M., & Ysa, T. (2007). Public policies on corporate social responsibility: The role of governments in Europe. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(4), 391–407.

Amable, B. (2003). The diversity of modern capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Auld, G., Gulbrandsen, L., & McDermott, C. (2008). Certification schemes and the impact on forests and forestry. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 33, 187–211.

Becker, U. (2008). Open varieties of capitalism: Continuity, change and performances. London: Palgrave.

Berthelemy, J. C. (2006). Bilateral donors’ interest vs recepients’ development motives in aid allocation: Do all donors behave the same? Review of Development Economics, 10(2), 179–194.

Campbell, J. L. (2006). Institutional analysis and the paradox of corporate social responsibility. American Behavorial Scientist, 49, 925–938.

Campbell, J. L. (2007). Why would corporations behave in responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 946–967.

Christopherson, S., & Lillie, N. (2005). Neither global nor standard: Corporate strategies in the new era of labor standards. Environment and Planning, 37(11), 1919–1938.

Clarke, N. (2008). From ethical consumerism to political consumption. Geography Compass, 2(6), 1870–1884.

Crane, A. (2000). Corporate greening as amoralization. Organization Studies, 21, 673–686.

Crane, A., & Matten, D. (2005). Business ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crouch, C. (2005). Models of capitalism. New Political Economy, 10(4), 439–456.

Crouch, C. (2006). Modelling the firm in its market and organizational environment: Methodologies for studying corporate social responsibility. Organization Studies, 27(10), 1533–1551.

Fransen, L. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and global labor standards: Firms and activists in the making of private regulation. New York: Routledge.

George, A. L., & Bennett, A. (2004). Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gerring, J. (2001). Social science methodology: A criterial framework. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gjolberg, M. (2009a). Measuring the immeasurable? Constructing an index of CSR practices and CSR performance in 20 countries. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 25(1), 10–22.

Gjolberg, M. (2009b). The origin of corporate social responsibility: Global forces or national legacies? Socio-Economic Review, 7, 605–637.

Gjolberg, M. (2010). Varieties of corporate social responsibility (CSR): CSR meets the Nordic model. Regulation and Governance, 4, 203–229.

Hall, P. D., & Soskice, D. W. (Eds.). (2001). Varieties of capitalism: The institutional dimensions to comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hughes, A., Buttle, M., & Wrigley, N. (2007). Organisational geographies of corporate responsibility: A UK–US comparison of retailers ethical trading initiatives. Journal of Economic Geography, 7, 491–513.

Jackson, G., & Apostolakou, A. (2010). Corporate social responsibility in Western Europe: CSR as an institutional mirror or a substitute? Journal of Business Ethics, 94(3), 371–394.

Jackson, G., & Deeg, R. (2008). From comparing capitalisms to the politics of institutional change. Review of International Political Economy, 15(4), 680–709.

Kang, N. & Moon, J. (2011). Institutional complementarity between corporate governance and corporate social responsibility: A comparative institutional analysis of three capitalisms. Socio-Economic Review. doi:10.1093/ser/mwr025.

Kinderman, D. (2009). Why Do Some Countries Get CSR Sooner, and in Greater Quantity, than Others? The Political Economy of Corporate Responsibility and the Rise of Market Liberalism Across The OECD: 1977-2007. WZB Discussion Paper.

Kinderman, D. (2011). Free us up so we can be responsible! The co-evolution of corporate social responsibility and neo-liberalism in the UK, 1977–2010. Socio-Economic Review. doi:10.1093/ser/mwr028.

King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Knopf, J., Kahlenborn, W., Hajduk, T., et al. (2011). Corporate social responsibility: National public policies in the European Union. Brussels: European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion.

Koch, D. J., Westeneng, J., & Ruben, R. (2007). Does marketisation of aid reduce the country-level poverty targeting of private aid agencies? The European Journal of Development Research, 19(4), 636–657.

Kollman, K., & Prakash, A. (2002). EMS-based environmental regimes as club goods: Examining variations in firm-level adoption of ISO 14001 and EMAS in UK, US, and Germany. Policy Sciences, 35, 43–67.

Kriesi, H., Koopmans, R., Duyvendak, J. W., & Giugni, M. G. (1992). New social movements and political opportunities in Western Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 22(2), 219–244.

Lee, E. M., Park, S.-Y., Rapert, M. I., & Newman, C. L. (2011). Does perceived consumer fit matter in corporate social responsibility issues? Journal of Business Research, 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.02.040.

Lee, M.-D. P. (2011). Configuration of external influences: The combined effects of institutions and stakeholders on corporate social responsibility strategies. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(2), 281–298.

MacDonald, K., & Marshall, S. (2010). Fair trade, corporate accountability and beyond: Experiments in globalizing justice. Farnham: Ashgate.

Maignan, I., & Ralston, D. (2002). Corporate social responsibility in Europe and the US: Insights from businesses “Self-presentation”. Journal of International Business Studies, 33, 498–514.

Mamic, I. (2004). Implementing codes of conduct. Sheffield: ILO & Greenleaf.

Marini, M., & Singer, B. (1988). Causality in the social sciences. Sociological Methodology, 18, 347–409.

Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008). Implicit and explicit CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 404–424.

Micheletti, M. (2003). Political virtue and shopping: Individuals, consumerism and collective action. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Middtun, A., Gautesen, K., & Gjolberg, M. (2006). The political economy of CSR in Western Europe. Corporate Governance, 6(4), 369–385.

Nölke, A. (2008). Private governance in international affairs and the erosion of coordinated market economies in the European Union, Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies Working Paper.

Palan, R., & Abbott, J. (1996). State strategies in the global political economy. New York: Pinter.

Parsons, W. (1995). Public policy: An introduction to the theory and practice of policy analysis. Brookfield and Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

Prakash, A., & Potoski, M. (2007). Collective action through voluntary environmental programs: A club theory perspective. Policy Studies Journal, 35(4), 773–792.

Sasser, E., Prakash, A., Cashore, B., & Auld, G. (2006). Direct targeting as an NGO political strategy: Examining private authority regimes in the forestry sector. Business and Politics, 8, 1–32.

Slater, D., & Bell, M. (2002). Aid and the geopolitics of the post-colonial: Critical reflections on new labour’s overseas development strategy. Development and Change, 33(2), 335–360.

Steen Knudsen, J., & Brown, D. (2011). CSR Initiatives and National Institutions: Do corporate activities reflect the welfare goals of the state? Presented at the Society for the Advancement of Socio-Economics (SASE) Annual Conference, June 23–25, Madrid.

Steuer, R. (2010). The role of governments in corporate social responsibility: Characterising public policies on CSR in Europe. Policy Sciences, 43, 49–72.

Van Tulder, R., & Van der Zwart, A. (2006). International business-society management: Linking corporate responsibility and globalization. London: Routledge.

Whitley, R. (1999). Divergent capitalisms. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Witt, M. A., & Redding, G. (2011). The spirits of corporate social responsibility: Senior executive perceptions of the role of the firm in society in Germany, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and the USA. Socio-Economic Review. doi:10.1093/ser/mwr026.

Acknowledgments