Abstract

The extant literature on comparative Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) often assumes functioning and enabling institutional arrangements, such as strong government, market and civil society, as a necessary condition for responsible business practices. Setting aside this dominant assumption and drawing insights from a case study of Fidelity Bank, Nigeria, we explore why and how firms still pursue and enact responsible business practices in what could be described as challenging and non-enabling institutional contexts for CSR. Our findings suggest that responsible business practices in such contexts are often anchored on some CSR adaptive mechanisms. These mechanisms uniquely complement themselves and inform CSR strategies. The CSR adaptive mechanisms and strategies, in combination and in complementarity, then act as an institutional buffer (i.e. ‘institutional immunity’), which enables firms to successfully engage in responsible practices irrespective of their weak institutional settings. We leverage this understanding to contribute to CSR in developing economies, often characterised by challenging and non-enabling institutional contexts. The research, policy and practice implications are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has become a global phenomenon, which has continued to permeate and influence discourses, policies and practices (Scherer and Palazzo 2011). As a global phenomenon, it comes with significant implications for firms in both developed and developing economies (Jamali 2010). However, the extant literature argues that CSR requires certain conditions and institutional arrangements to function—i.e. strong government, market and civil society (Matten and Moon 2008; Aguilera and Jackson 2003; Gjolberg 2009; Husted and Allen 2006; Langlois and Schlegelmilch 1990; Maignan and Ralston 2002; Muller 2006). In that regard, most comparative CSR analytical frameworks, in their accounts, often implicitly assume strong institutional contexts, which put “…pressures on companies to engage in such CSR initiatives” (Aguilera et al. 2007, pp. 847–848), especially in developed market contexts. As such, it is argued that CSR is not likely to occur if these conditions and institutional arrangements are weak or absent (Campbell 2007; Deakin and Whittaker 2007; McWilliams and Siegel 2001).

Another assumption, which is similar in many ways to the ‘strong institution’ assumption, is the view that firms have a significant agency (Giddens 1984) to overcome their institutional constraints. In other words, Corporate Social Irresponsibility (CSIR) (Lawton et al. 2014) can only be a matter of a corporate strategic choice (Child 1972), and firms cannot be victims of some institutional incentives for irresponsibility. This latter assumption of corporate agency as a lens to explain CSR practices particularly finds expressions in studies on CSR in developing economies (Hamann et al. 2005; Jamali et al. 2009; Azmat and Samaratunge 2009), often marred by the significant absence of ‘western capitalist institutions’.Footnote 1

The logic of these oftentimes institutional theory-based views is that CSR in developing (and developed economies) requires strong and effective market institutions; and the implied conclusion seems to be that CSR would either not exist or would not be effective in developing economies, beyond mere philanthropy (Campbell 2007). As a result, studies in this space have mostly documented conditions that will make responsible entrepreneurship and CSR difficult and somewhat impossible in weak institutional settings. For example, in their paper on Medium and Small size Enterprises (MSEs), Azmat and Samaratunge (2009) highlight some propositions, which explain the underdevelopment of CSR in challenging and non-enabling institutional contexts.Footnote 2

If we accept these views, how do we then explain the manifestations of (non-philanthropic) CSR in challenging and non-enabling institutional contexts (see WEF 2011, for some examples of sustainability champions from emerging markets), where the consequences of irresponsibility are often limited? The answer to this puzzle is still unknown, as there have been limited efforts aimed at investigating how local firms (not multinationals) pursue and achieve responsible business practices in developing economies, with a specific focus on the presence and implications of institutional voids Footnote 3 for CSR in these contexts. As such, it has become important to address this paucity of research given the increasing occurrence and impact of CSR activities pursued by local firms in such contexts; especially in Africa—a continent characterised by weak institutional arrangements and segmented business systems (Wood and Frynas 2006), if assessed on the indices of the western varieties of capitalism. Some of these firms—e.g. Equity Bank, Kenya—have been internationally recognised as sustainability champions (WEF 2011). Nonetheless, for every visible ‘Equity Bank’, there could be dozens of hidden sustainability champions in Africa.

In this paper, we focus on these often neglected firms in the literature, which could be role models for CSR in Africa, and seek to identify the drivers of CSR and the strategies employed. This quest is unique given that there could be more incentives for irresponsibility than responsible business behaviours in such contexts. In the light of the research gap, our main research question was developed: why and how might local firms pursue CSR practices in weak institutional contexts? Drawing from the unique case of Fidelity Bank,Footnote 4 Nigeria, our objective is to contribute to the understanding of corporate social activities in challenging and non-enabling institutional contexts, through a theory elaboration process (Lee 1999) aimed at identifying and connecting institutionalism-based explanations of CSR activities in weak institutional settings.

The choice of Nigeria and Fidelity Bank is not arbitrary. On the one hand, the business governance and responsibility context in Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, which has been characterised as poor in regulatory quality, high in corruption and low in government effectiveness (Kaufmann et al. 2008), provides a useful case study to examine CSR in non-enabling institutional contexts. It is also a rich empirical site to explore ‘CSR in institutional voids’ because it requires balancing different local and international demands, thus raising important issues about what can be considered universal and what needs adaptation to local circumstances (Bondy and Starkey 2014). On the other hand, Fidelity Bank has been recognised for its CSR values, innovations and practices. For example, the bank was recently honoured for its efforts in CSR at the Nigeria CSR Awards in 2013 and in 2014, where the bank received the highest nominations. Furthermore, the bank received the award for “Best company, youth focused CSR” in recognition of its impactful programmes, services and projects that directly impact the youth in the various communities in which they do business.Footnote 5 Fidelity Bank also provides a useful case study because it is a completely local (Nigerian) bank, with no international operations, thus enabling an examination of how CSR can be pursued by indigenous firms despite the challenges of their institutional contexts.

Through a set of qualitative in-depth interviews, focus group discussions and documentary analysis, our research question enabled us to make two concrete contributions by theorising and extending the literature on CSR in developing countries (Jamali 2007; Jamali et al. 2009; Blowfield and Frynas 2005). Firstly, we add to the CSR literature using institutional theory to explain the motivations/rationale behind the pursuit of responsible business practices in weak institutional contexts, despite the complex and negative institutional voids confronting our case organisation (Fidelity Bank), and how these combine to constitute unique CSR adaptive mechanisms within firms. In this regard, we show how firms can, by themselves (through CSR adaptive mechanisms), remain socially responsible in weak institutional settings. Secondly, we make a contribution by explaining ‘how’ firms use CSR practices to fill institutional voids. These contributions help to capture and understand the possible governance and political role of CSR in most developing countries constrained by weak institutions; and it is anticipated that insights from this study can be utilised by other firms operating in similar settings.

The following parts are structured into four sections. First, we explore CSR across contexts, paying attention to its drivers, motivations and variations. Secondly, we present our research methodology and approach. Thirdly, we present the analysis of our data and results to show why and how CSR can occur in challenging and non-enabling institutional contexts. Lastly, we present further discussions, contributions and implications for research, practice and policy.

CSR in Context: Drivers, Motivations and Variations

CSR comes with different perspectives and meanings in different cultural settings (Habisch et al. 2005). As a result, there are as many definitions of CSR, as there are writers thus leaving the construct ambiguous (van Marrewijk 2003; Gobbels 2002; Henderson 2001) and open to conflicting interpretations (Windsor 2001). Despite the varying definitions, Caroll (1991, p. 42)’s suggestion that “the CSR firm should strive to make a profit, obey the law, be ethical, and be a good corporate citizen” is very dominant. At the heart of this suggestion is McWilliams and Siegel’s (2001, p. 117) description of CSR as “actions that appear to further some social good, beyond the interests of the firm and that which is required by law”. Arguably, these views are succinctly harmonised in a recent articulation of CSR by the European Commission (2011, p. 6), as “…the responsibility of enterprises for their impacts on society”. Notwithstanding, most articulations of CSR, however, often seem to reflect the characteristics of advanced free market societies with strong governance institutions and less institutional voids.

Beyond defining CSR, which is a very problematic task fraught with contestations (Amaeshi and Adi 2007; Okoye 2009), it is recognised in the extant literature that CSR is driven by many factors including managerial values (Hemingway and Maclagan 2004; Visser 2007), organisational characteristics (Aguinis and Glavas 2012), and institutional pressures and configurations (Matten and Moon 2008). At the managerial level, powerful personalities within organisations are constructed as moral change agents who leverage their legitimacy and personal values to sway organisation level agenda and actions (Visser 2007). CEOs and business leaders are often considered to be such personalities (Witt and Redding 2012), although Hemingway (2005) has argued that this form of ‘corporate social entrepreneurship’ could “…operate at a variety of levels within the organisation: from manual workers or clerical staff to junior management through to directors” (p. 236, emphasis in original). This exhibition of managerial or employee heroism is well documented in the corporate greening (e.g. Fineman and Clarke 1996; Crane 2001) and ethical leadership literatures (e.g. Dukerich et al. 1990; Stahl and Sully de Luque 2014) (see Amaeshi 2009). Furthermore, a key theme central to these is the emphasis they place on the centrality of the ‘manager’ in shaping firm behaviour.

At the organisational level, CSR has been found to be driven by a myriad of factors including organisational innovation (Asongu 2007; Hull and Rothenberg 2008; Porter and Kramer 2002), culture (Bansal 2003; Maon et al. 2010; Aguinis and Glavas 2012), size and ownership (Gallo and Christensen 2011), financial strength (Orlitzky et al. 2003; Campbell 2007) industry type and structure (McWilliams and Siegel 2001; Campbell 2007), et cetera. And from an institutional perspective, it is argued that “CSR is located in wider responsibility systems in which business, governmental, legal, and social actors operate according to some measure of mutual responsiveness, interdependency, choice, and capacity” (Matten and Moon 2008, p. 407—emphasis ours), hence the variation of CSR across countries and institutional contexts (Chapple and Moon 2005; Campbell 2007; Kim et al. 2013; Amaeshi and Amao 2009; Jamali and Neville 2011).Footnote 6

In this paper, we focus on the interface between the organisational and institutional dimensions of CSR. Building on DiMaggio (1988), we define institutions as formal and informal enduring constraints that structure the economic, political and social relationships between a business and its environment (such as CSR). We refer to institutions as abstract constraints such as widely held norms that constrain behaviour, legal regimes and the way they are enforced, and real justice in the rule of law. We also refer to institutions in the concrete sense, such as patterns of cooperation and competition among firms, the role of technical societies and governments, capital markets, regulation, NGOs and employee programmes (Eggertsson 2005; Nelson 2008). The literature argues that where some of these are significantly absent, there is a higher tendency for institutional voids to exist, and therefore constitute challenges and non-enabling contexts for CSR.

CSR and Institutional Voids

The theory around institutional voids is not new in the management literature (Khanna and Palepu 2010). With origins in institutional theory, according to Mair and Marti (2009, p. 422), for instance, institutional voids represent situations “where institutional arrangements that support markets are absent, weak, or fail to accomplish the role expected of them”. They note that the absence of institutions does not imply the existence of an institutional vacuum but that institutional voids are as a result of the “absence of institutions that support markets in contexts that are already rich in other institutional arrangements” (Mair and Marti 2009, p. 422). Other scholars highlight that the success or failure of market economies depend on how much they reflect the essential characteristics of the advanced capitalist political economies (Wood and Frynas 2006), which are the foundations of CSR in these economies. In that regard, if the advanced capitalist model is the minimum requirement for the proper functioning of CSR, as an organisational practice (Vogel 2005; Matten and Moon 2008), and if one accepts the view that “CSR is located in wider responsibility systems in which business, governmental, legal, and social actors operate according to some measure of mutual responsiveness, interdependency, choice, and capacity” (Matten and Moon 2008, p. 407—emphasis ours), it may be inevitable to doubt the utility function, feasibility, efficacy, efficiency and effectiveness of CSR in institutional contexts marred by inefficient markets, poor governance and weak civil societies.

Nonetheless, the weak institutional contexts in which firms in developing economies operate are often taken for granted or at best theorised away simply as ‘different institutional contexts’, which per se do not require further unpacking. This relativist approach to the understanding and function of CSR in society has come to dominate the nascent comparative CSR studies, especially those on developing economies. In most cases, this is presented as a critique of the dominant Anglo-Saxon characterisation of CSR and the unwholesome export of CSR practices from the North to the South (see Amaeshi et al. 2006). In these countries, firms try to create legitimacy and morality by signalling positive externalities and showcasing their social activities to different stakeholder groups.

While we appreciate the need to be critical of the Anglo-Saxonisation of CSR practices in different institutional contexts, the literature on CSR in the so-called South seems to pay limited attention to the fact that CSR, as a form of corporate self-regulation, is more than corporate philanthropy. It is also an essential governance mechanism of the market in advanced capitalist economies (Brammer et al. 2012; Amaeshi 2009, 2010; Crouch 2006), which is often weak in most developing markets. In other words, this literature appears to assume the relevance and suitability of CSR across institutional contexts and take for granted its supporting “…basic institutional prerequisites” (Matten and Moon 2008, p. 406)—i.e. functioning, independent and free markets, governments, vibrant civil societies and efficient legislative institutions. These basic institutional prerequisites are vital to understanding and explaining the complementary economic governance role of CSR practices in advanced political economies (Matten and Moon 2008; Aguilera and Jackson 2003).

From the foregoing, therefore, the capitalist political economy could be described as a collective apparatus of institutional accountability between the state, market and civil society. They work in tandem and re-enforce one another (Matten and Moon 2008). For example, the markets provide or deny finance to the state and the state in turn regulates the markets. Essential societal services that could not be provided through the market, due to market failure, are complemented by the state and or by the civil society. And the civil society in turn is free to hold the state and the market to account whenever necessary (Lawton et al. 2014). All these interactions among and between the different elements are founded on and bounded by the rule of law, which is embodied in free and fair legal institutions. The combinatory strength of each of these elements constitutes the distinguishing hallmark of the advanced capitalist economies necessary for CSR. We capture the key aspects of the institutional conditions for CSR as stipulated in the literature in Fig. 1.

Conversely, it is argued that the “[O]pportunities for CSIR increase in the absence of these conditions, as is evident in much of sub-Saharan Africa and the former USSR, with, for example, monopolistic companies exploiting capitalist economies or governments substituting regulation and administration of markets with rent seeking” (Matten and Moon 2008, pp. 406–407). In our attempt to explore these concerns further, we note that the literature on comparative CSR and particularly the budding literature on CSR in developing economies cannot ignore the view that most weak capitalist economies are marred by institutional voids—e.g. lack of vibrant capital markets, as well as weak states, legal environments and civil societies, which may undermine the complementary governance role of CSR in these economies.

In this regard, insights from Lepoutre and Valente (2012) are helpful in moving away from existing studies, which mainly examine how the governance function of CSR is undermined in weak contexts, to exploring how firms pursue and achieve responsible business practices in developing economies marred by institutional voids. As such we attempt to answer the question: why and how might local firms pursue CSR practices in weak institutional contexts? Our enquiry is guided by the extant literature on the institutional theorising of CSR in varieties of capitalism and the literature on responsible business practices in developing economies (Idemudia and Ite 2006; Eweje 2006; Azmat and Samaratunge 2009; Amaeshi et al. 2006; Adegbite et al. 2012, 2013; Adegbite 2014; Blowfield and Frynas 2005; Campbell 2007; Deakin and Whittaker 2007; McWilliams and Siegel 2001; Aguilera et al. 2006, 2007; Doh and Guay 2006; Matten and Moon 2008; Aguilera and Jackson 2003).

Research Context, Design and Methodology

Research Context

Nigeria is one of the fastest growing economies in the world, even though 70 % of its population still live below the poverty line (CIA 2012). It is Africa’s largest economy, amounting largely from its huge earnings from oil exports. Notwithstanding, Nigeria’s economy is struggling to leverage the country’s oil wealth in addressing poverty, weak infrastructure, poor electricity supply, insecurity and unemployment among other problems that affect majority of its population. Effective CSR can make significant positive contributions to the lives of Nigerians, majority of whom have lost confidence in the government, with regards to the provision of the basic necessities of life, but look up to businesses, especially multinationals, as beacons of hope (Adegbite and Nakajima 2011a). However, corporate corruption in large businesses, including incessant incidents of accounts manipulation, auditors’ compromise, non-transparent disclosure and other fraudulent behaviours continue to thrive in Nigeria due to the lack of the much needed cultural strength to internally address them by firms themselves, the regulatory authorities and the professional bodies (Adegbite and Nakajima 2011b).

In sum, the political economy of Nigeria is complex. It is a developing economy with a very unique and challenging institutional environment characterised by weak infrastructure provision, poor governance, weak public sector, inadequate private and property security, corruption, tax evasion, bribery, weak enforcement of contracts, and high cost of finance and of doing business (Amaeshi and Amao 2009; Okike 2007). It is from this context that we explore ‘why’ and ‘how’ CSR is possible using a single case study of Fidelity Bank.

Design and Methodology

Given the nature of the research questions, a qualitative research design was an appropriate methodological approach, which enabled us to focus on a micro-level firm analysis to create an understanding of the drivers, motivations and strategies of CSR in a weak institutional context. We followed a single case study approach in line with Eisenhardt (1989) and Bondy (2008) to contextualise the rich descriptions of how CSR initiatives were enacted in a weak capitalist economy. We decided to pick an in-depth single case study design, as our aim was to explore the processes of “why” and “how” CSR worked in Nigerian banks (Yin 2014; Bondy 2008).

The selection of Fidelity Bank was based on theoretical sampling. The bank was chosen because of its outstanding responsible business practices (at the Nigeria CSR Awards, 2013 and 2014) in an environment with very limited incentives to be socially responsible. As such, it serves as an outlier—a deviation from the norm—and thus fits very well as an appropriate ‘black swan’ (Flyvbjerg 2006; Yin 2014) and the ‘logic of a situation’ (Gibbert 2006, p. 146) for our study.Footnote 7 Moreover, the bank is a completely local (Nigerian) bank, with no international operations, thus enabling an examination of how CSR can be pursued by indigenous firms despite the challenges of their institutional contexts.

The case study methodology allowed for an in-depth study of Fidelity Bank Plc by offering a very specific and intensive investigation into the dynamics that shape their CSR within the Nigerian setting (Eisenhardt 1989). We thus focused on a bounded and specific organisational setting and scrutinized the activities and experiences of Fidelity Bank in CSR, as well as the context in which these activities and experiences occur (Stake 2000). As Cooper and Morgan (2008, p. 160) argue, the case study research approach proved useful to investigate our research question, given that it was related to “…complex and dynamic phenomena where many variables, including variables that are not quantifiable, are involved…actual practices, including the details of significant activities that may be ordinary, unusual, or infrequent [and] phenomena in which the context is crucial because the context affects the phenomena being studied, and where the phenomena may also interact with and influence its context”.

Data Sources

Data collection spanned ten months (Sept 2013–June 2014) and was driven by a purposive sampling technique (Eisenhardt 1989). The process began with the researchers drawing insights from in-depth interviews using semi-structured questions with the Head of CSR and Community Relations (and also the Coordinator, Fidelity Helping Hand Programme) as well as the Head of Marketing Communications at Fidelity Bank in the last quarter of 2013.Footnote 8 The respondents were sent an interview guide to facilitate their preparation and to gain cooperation (Lynn et al. 1998) in line with previous studies (see for example, Filatotchev et al. 2007; Hendry et al. 2007). Interviews lasted around 70 min and generated well over 6,000 words of texts. We triangulated the interviews with documentary evidence and archival data, which were helpful to appropriately contextualise our research in the Nigerian banking industry setting prior to conducting interviews. This also ensured we enhanced validity and reliability by sharing our findings with the senior executives interviewed from Fidelity to see if our analysis tracked their reality.

The data collection process also included a focus group session with principal CSR officers including senior management staff in June 2014. The latter data collection efforts helped to compare, as well as gather further evidence on the themes that emerged from the prior interview data. The focus group session had 9 members. This small number helped to increase the efficiency of the focus group session and enabled members to freely discuss CSR in Nigeria (see Ewings et al. 2008). Participants were drawn from different backgrounds and functions, in order to ensure representativeness and diversity of perspectives. More importantly, discussions were tape-recorded and took around 109 min.Footnote 9

Data Analysis

As with most inductive studies that are in-depth single cases, the first phase of the data analysis was a pilot, which constituted some familiarisation and sense making of the data on CSR in Nigeria. This suggested some patterns around the drivers of CSR in Nigeria as it related to the weak institutional environment. This enabled the development of a coding scheme around these emergent themes. Raw extracts from the interviews and focus group data had been employed in discussing the themes that emerged from the data (Saunders et al. 2009). The interpretation of the data suggested some patterns around the nature of CSR in Fidelity Bank, its foundations, motivations, orientations, activities, strategies, institutional constraints and influences.

Despite triangulation, this methodology can be predisposed to respondents’ position bias, which may influence them to over report past events and strategies, or present themselves and Fidelity Bank in a socially desirable image (Miller et al. 1997), especially at the expense of others. Thus, in order to minimise these effects, we ensured that the interviews satisfied the purposive sampling requirement of competence and experience (Hughes and Preski 1997) and that the managers interviewed could describe the CSR environment more competently than other members of the organisation (Payne and Mansfield 1973). The texts generated from the interviews, focus group discussions and documents were qualitatively analysed with Nvivo 8 and the inter-coder reliability was well over 85 %. We conducted a timeline to understand the “why” and “how” questions by coding interview and focus group data as well as documents, including a 10-year documentation of Fidelity Bank’s CSR activities. With the large amounts of primary data, documents from news’ reports, company reports and press releases, we developed codes to support the development of theoretical logics from our data. Thereafter, we used quotes and observations to create an interpretive model to answer our research question. The next part will look at the findings.

Findings

This section is broadly organised to capture the “why” and “how” aspects of our research question, as detailed below. It explores a range of identified adaptive mechanisms which inform Fidelity bank’s CSR strategies despite its weak institutional context. The complementary and reinforcing relationship between these CSR adaptive mechanisms and strategies is further engaged with in the discussion section.

CSR Drivers in Weak Institutional Contexts

Our data reveal that the major reasons behind CSR in weak institutional contexts include (1) the private morality and sense of stakeholder fairness of the firm and (2) the firm’s quest for social legitimacy informed by complementary local and international norms to its private morality and sense of fairness. These reasons, which are intertwined, influence how the firm navigates responsibly through the challenges of its weak institutional context, and are sustained and reinforced by the commercial benefits they bring to the firm, as explained below.

Private morality is used here as the opposite of institutional power, which is the embodiments and expressions of public morality. Private morality is rather the expression of personal values and beliefs, which are voluntarily expressed and not necessarily compelled by public institutions—e.g. the law. Fidelity Bank’s CSR practices are found to be mainly informed and influenced by the bank’s sense of morality:

We do CSR from the perspective of morality and the sense of doing good, doing what is right … because it is the right thing to do. … We need to leave the world a better place for all of us and the generation unborn; we want to leave the world a better environment than we met it both locally and globally (focus group)

The view of CSR as a form of moral obligation, which is based on a compassionate predisposition to present and future stakeholders is strongly reflected in the interviews, as well as the focus group discussions. A principal CSR officer in the bank observes that:

The basic reason why we do CSR is because we care. It is a personal thing; we are citizens of this nation; there is a role for us, both as a private entity and as individuals; we are responsible persons who make up this responsible organisation. We do it because we care; because we have benefited from the society. We will continue to impact our society.

This moral sense of duty and fairness is not only restricted to external stakeholders but also finds expression in how the bank relates to its internal stakeholders—i.e. its employees:

We also pay attention to our employees, their pay, and their work-life balance. For example, even though there is a policy (an informal widespread practice in the industry) that you don’t get paid if you get pregnant when you just join a company, we relax such rules here to promote family life balance. We have won the ‘best place to work’ award and the most ‘family friendly company’ for the past 4 years.

It is important to note that these practices are luxuries in most Nigerian firms and especially in banks, where women are usually dismissed when they get pregnant in their first 5 years of employment. This suggests an internally driven normative need towards a higher order value of doing the right thing through a stewardship approach to staff well-being, which is anchored on and strongly supported by the leadership of the bank:

If the CEO does not think that it matters, it won’t matter in the organisation. In the 25 year history of the company, we have had just 2 CEOs, the previous one was also compassionate; we have, by the grace of God, had very compassionate CEOs, so that is why you see the kind of things that we do. (Head of Marketing)

The commitment to private morality and stakeholder fairness allows Fidelity Bank to make financial services easy and accessible; and connects it with the goals of sustainable economic development, poverty reduction, environmental responsibility and social relevance. This way, Fidelity Bank contributes “to ensuring that the costs of economic development do not fall disproportionately on those who are poor or vulnerable, that the environment is not degraded in the process, and that renewable natural resources are managed sustainably” (Fidelity Bank 2014).

In addition to private morality, it is cultural in most African countries for individuals to express themselves and their identities through their communities (Menkiti 1984). This local norm of communal existence, which is often idealised as the Ubuntu philosophy—also finds expression in the corporate world. It is a quest for belongingness—a connection to one’s root and collective identity. This came out strongly and frequently in our data. The interviewees, for example, expressed the need to gain societal legitimacy through CSR activities, which are considered beneficial to their immediate business environment. As one of the focus group participants put it: “the way to be loved by the citizens of a community is to be seen to do good.” This quest for social legitimacy, which is seen as a “drive to give our business a human face” (focus group participant), finds expression in the articulation of CSR as:

“…a way of giving back from what your customers have given to you as a corporate entity. It is a way of giving back to the community, and society, for appreciating me, for coming to me to buy, then for me to say thank you. CSR becomes a tool for saying thank you …In other places, saying thank you may not mean a lot; but in our context here in Nigeria, people still believe that matters and expect it. If you don’t say thank you by doing CSR, nobody is going to kill you, and no one is going to say they won’t buy from you. However, when you reach out, you get this feel good feeling that you have done good. You need to be fair to your stakeholders.” (Focus group respondent—the emphasis in italics is ours and shows that firms are not necessarily under pressure to be socially responsible in this context)

Beyond the quest for social legitimacy informed by local norms, Fidelity Bank also follows and adopts practices shaped by complementary international norms. For instance, the bank subscribes to the Nigerian Sustainable Banking Principles (NSBP) as well as the Equator Principles in managing environmental and social risks in its own undertakings as well as that of the clients it finances (Fidelity Bank 2014).Footnote 10 One can argue that the global sustainability movement is a quest for harmony, connectivity, security, inclusion and equity (Gladwin et al. 1995; Lepoutre and Valente 2012)—a quest which is very much in consonance with the local norm of communal existence, as well as with the bank’s private morality and sense of fairness. As expressed by the Group Head of Marketing Communications:

By adopting the Equator Principles, we show once again that sustainable and responsible actions even in strategic business choices will always remain our watch word (Fidelity Bank website, June 2014).

Ultimately, these drivers of CSR in the bank also lead to some commercial (instrumental) benefits, which sustain and reinforce them:

Every day you hear banks being attacked by armed robbers in Nigeria, but Fidelity Bank is never attacked, it is because of the goodwill we receive from our CSR (Focused group respondent)

In summary and in line with Aguilera et al. (2007), the foregoing suggests that Fidelity Bank’s CSR practices are broadly influenced by normative (private morality) and relational (social legitimacy) motives, which translate to some and instrumental (commercial benefits) outcomes. Although they have been presented as isolated factors, in reality, they tend to interact and co-exist (Aguilera et al. 2007) in different configurations, as highlighted below:

Our CSR practices are driven by our strong values and beliefs (private morality). We see CSR as an opportunity to demonstrate our commitment to society, as a good corporate citizen (social legitimacy) (focus group extract, June 2014; insertion of constructs, ours)

Our commitment to responsible banking begins with taking clear and ethical actions (private morality) that guide the processes and ways in which business is done in our bank. By adopting the Equator Principles (social legitimacy; international norm), we show once again that sustainable and responsible actions even in strategic business choices will always remain our watch word. …. As a responsible institution, Fidelity Bank will continue to endorse and support any robust initiative that makes [sic] for wholesome living for Communities where we do business (social legitimacy; local norm) (Group Head, Marketing Communication, Fidelity Bank, website accessed June 2014; insertion of constructs, ours)

In Table 1, we have provided some descriptions as well as evidence from the Fidelity case study to summarise the rationales for CSR in a weak institutional context.

CSR Strategies in Weak Institutional Contexts

The norms of private morality and social legitimacy described above in turn inform the CSR strategies of the Bank. Here, we identify how Fidelity Bank developed two main strategies in their pursuit of responsible business practices: (1) democratisation and empowerment for localisation and (2) collaboration for impact and institutional entrepreneurship. Each of these strategies is further explored next.

Democratisation and Empowerment for Localisation

Democratisation and empowerment both reflect the sense of internal stakeholder fairness and the quest for social legitimacy—particularly in line with the international norms of liberal democracy (Olssen 2004; Agger and Löfgren 2008; Sasse 2008). Fidelity Bank spends around USD1 million each year on CSR through diverse projects across Nigeria. Recent examples include the renovation of schools, provision of water to prisons, facilities for widows, computers for the blind, as well as incubators and other equipment for hospitals. Due to the diverse set of staff across the country coming up with these ideas, Fidelity Bank operates a bottom–up approach where the business units (i.e. the bank branches serving different communities) drive the CSR activities of the bank, given their proximity to local communities. According to the head of CSR,

We try to avoid the popular norm in Nigeria which is the centre approach where the head office directs what is going on regarding CSR initiatives across the organisation. I am not in Lokoja, or Adamawa, or Yola, but the staff there will know the needs of those communities… the person in Abeokuta who takes ownership of a programme will want it to succeed, as he sees the needs that the programme will meet in his immediate community and he will have a sense of joy for seeing it happen. Above all, when CSR is entirely a head office function, you see that when people at the head office lose interests, everybody in the company all over loses interest. So we have democratised the process and people are working on it in branches; so even if people at the head office are not doing extremely well, people will ask questions and their own enthusiasm will make you wake up from your slumber. That is why it has worked well for us and we have achieved a lot in the past 10 years. (Head of CSR)

This way, CSR in Fidelity Bank is democratised and the bank is able to meet diverse human needs especially in critical areas (“Members vote on the CSR projects, including senior and junior staff. It is a democratic process”. —focus group respondent). It is organised through the “helping hands ambassadors” in each of the over 200 branches of the bank nationwide. Some branches have more than one ambassador in them, including very senior management staff, such as vice presidents, who help to create and raise CSR awareness in their branches. The ambassadors manage the CSR activities within the guidelines provided, for example on the timeframe for the execution of projects. The Head of CSR does overall management and supervision of the CSR projects.

We try not to micro-manage since we have approved the programme. We want that sense of ownership; we take weekly reports. After we have commissioned, the ambassadors are encouraged to keep visiting the projects. When we did good pasturing in Kano orphanage; we took the names of the 33 kids and their birthdays. The staffs [sic] still go back there to celebrate with them on their birthdays with cakes etc. The social connection is there. (Head of Marketing)

CSR is thus driven in the bank under certain platforms such as the Fidelity Helping Hands Programme, which is a staff-driven initiative, where employees raise money among themselves to meet the needs of the communities and intervene in their communities. Thereafter, the money raised is matched by the bank, to demonstrate corporate commitment. The Fidelity Helping Hands Programme oversees the philanthropic and social welfare impact initiatives aimed at creating a revolution of good works where every stakeholder in every community is challenged to do some good within that community and uplift the lives of the people. This strategy came as a result of the realisation that many CSR programmes are often considered ‘head office projects’ where employees involved do not have any kind of affinity towards the project or programme or a sense of ownership. As a result, CSR programmes in Fidelity Bank have been successful due to the significant bank-wide support that this strategy provides. This makes their CSR effective, with or without top management direct involvement. This localisation of CSR decisions also allows for the application of local knowledge, which is necessary for securing social legitimacy and address pertinent real-life challenges (Idemudia and Ite 2006; Eweje 2006; Azmat and Samaratunge 2009).

Collaboration for Impact, Institutional Entrepreneurship and Filling Institutional Voids

Another strategy employed by Fidelity Bank, which featured prominently in our data, is partnership. Arguably, this reflects the communal norm of Ubuntu and self-governance (i.e. private morality). It is often applied to many different initiatives. For example, on their CSR activities on environmental preservation and beautification, they work with public institutions including State and Local Governments, as well as advocacy groups such as the Nigerian Conservation Foundation, and other corporate partners such as Chevron and Mobil—both oil and gas companies.

We collaborate with other organisations, not necessarily banks, but NGOs, governments (Focus Group Respondent)

The respondents further highlighted some institutional constraints and challenges, which affect the cost of CSR. Some of these challenges relate to the lack of institutional support, particularly from the government. The head of CSR notes as follows:

Some governments understand what you want to do and are excited about it; some don’t, but think you have a lot of money as a corporate organisation and bill you a lot of money before allowing you to help the society. Indeed you are trying to help the society that they should have helped but neglected. And when you try to take the burden off them, they say you are also doing marketing… So at times, we look at the cost of doing CSR which can be discouraging; but we don’t stop since someone doing the wrong thing is not a good enough reason for us to stop doing the right thing. If you stop, you are validating their actions

In order to overcome these challenges, there is therefore the need for more stakeholder partnership in minimising the institutional constraints facing CSR. This suggests the commitment of Fidelity Bank to a collaboration strategy with other institutional agents.

Apart from the government and NGOs, the media is very important as they are the people that tell the world what we have done, why we have done it and the plight of the people that we have met, including what problems have been solved and those that remain and what others can do to help (Head of Marketing)

For example, when the focus of the country/government was to stop rice importation, the bank partnered with a rice farm in Abakaliki to get it to run smoothly through loans which are not excruciating in order to help their production capacity. Our efforts help government initiatives and focus. (Focus Group Respondent)

These could be interpreted as instances of “institutional entrepreneurship” (DiMaggio 1988; Fligstein 2001) in terms of promoting CSR in developing countries. Although theories of entrepreneurship and institutions might have grown up in isolation, they are complementary (Yang 2004). The case of Fidelity Bank indicates that institutional voids in developing economies may present an opportunity for entrepreneurs (firms) to pursue CSR by acquiring institutional support for CSR activities without allowing weak institutions to destroy or corrupt those activities. This helps to create sustainable and fair businesses, where externalities are minimised. This can manifest as filling institutional voids and or building/strengthening institutions, as succinctly expressed by a focus group participant:

CSR is a channel by which we get those things government are not giving to the people to them. (Focus Group Respondent)

In the absence of strong capital and loan markets, for example, the need to provide access to finance to the excluded and the hard to reach has led to the increasing focus on financial inclusion, as a solution, by the financial services sector. This problem arises due to institutional voids in the provision and spread of finance in the economy. Fidelity Bank proactively strives to fill this gap in an equitable manner, as expressed below:

Fidelity Bank’s mission is to make financial services easy and accessible. Execution of this mission connects us with the goals of sustainable economic development and poverty reduction… This way we contribute to ensuring that the costs of economic development do not fall disproportionately on those who are poor or vulnerable, that the environment is not degraded in the process, and that renewable natural resources are managed sustainably. (Fidelity Bank website, June 2014)

As could be imagined, one of the challenges of most weak institutional contexts is the enforcement of laws and regulations (Graham and Woods 2006; Brown and Woods 2007)—a situation which often leads to governance void and failure. Firms can display great informal power to impose activities as a result of the weak institutional system. In its attempts to contribute to filling institutional voids, the Bank also engages in activities, which address institutional environmental governance voids, as illustrated through its voluntary adoption of Environmental and Social (E&S) risks management system:

Fidelity may be exposed to the E&S risks associated with the underlying business activities of its clients. These risks often present as credit and/or reputational risk. Our fit-for-purpose E&S systems and processes have therefore been developed to respond to the nature and scale of client operations, sector, nature of E&S risks and potential impacts. Our decision-making processes incorporate an approach that systematically identifies, assesses and manages E&S risks and their potential impacts. Where avoidance of E&S risk is not possible, the Bank engages with the client to minimise and/or offset identified risks and impacts, as appropriate. The bank believes that its regular engagement with clients and third-party suppliers about matters that directly affect them plays an important role in avoiding or minimising risks and impacts to people and the environment. Fidelity also recognises the importance of supporting sector-wide market transformation initiatives that are consistent with sustainable development objectives. Our Bank screens all Project Finance loan applications for E&S risks and maintains a database of E&S risks inherent in transactions processed. (Fidelity Bank, June 2014)

Further on environmental preservation, the bank has also pioneered the use of recycled biodegradable paper as cash bags, given that Nigeria is largely a cash-based economy. This allows Fidelity Bank to extend beyond philanthropic CSR activities to CSR as a private governance of externalities, such as the environmental impact of banking activities. Activities such as these do not only make economic sense in terms of cost reduction, but they also contribute to reducing the negative impacts of the Bank on the environment.

When people come for large withdrawals, the norm is to use polythene bags; but this impact negatively on the environment due to carbon foot-printing (Head of CSR)

In terms of institution building, Fidelity Bank is also very instrumental in promoting the Nigerian Sustainable Banking Principles, in collaboration with other actors, thus distinguishing the bank as an institutional entrepreneur.

Given the high level of illiteracy in Nigeria, as well as the increasingly poor level of education, corporations such as Fidelity contribute to education by encouraging the development of talents, such as in writing for example. As government funding on education has only increased in recent years, firms like Fidelity bank help to address this institutional gap in education, talent development and entrepreneurship, as many of their mentored writers can now earn a living from their works. A focus group respondent illustrates this with the following quote:

Let it be said that Fidelity in its existence made sure that children who didn’t have access to education are provided such access based on our projects; let it be said that the girl child who is marginalised has got her right standing in the society through our efforts on educational financing. For example, we go to schools where there are dilapidated facilities, where people don’t have the right access to education and we refurbish them; give them facilities such as computers. We are change agents. We are addressing the neglect of government. (Focus Group Respondent)

Fidelity Bank has pioneered the creative writing workshop to support many talented (upcoming) writers with training and mentoring by internationally acclaimed writers. 50 writers are selected each year through competitions and are exposed to the experiences of these experts. The head of CSR notes as follows in relation.

We have been doing this for the past 6 years; others have started doing the same. We are pace setters… We took the creative writing workshop online (as it was limited to only 50 people every year), so we have our consultants provide topics and feedback to our young writers on a weekly basis, so we can reach more people. This is an on-going thing, through the year. Some of the people who have come through our training have gone on to win international competitions.

In sum, these activities could largely be characterised as expressions of extended corporate citizenship (Matten and Crane 2005) and informal institutional work because, although firms do not have the power of enforcement of the State, they have an analogous power of the State (Crane et al. 2008) in their value chain—especially with their direct suppliers or their deep pockets (Amaeshi et al. 2008). In that sense, firms exert coercive pressure and shape social obligation to raise finance in a direct form. Thus, firms could be sources of financial support in providing a complementary governance structure (Jacobsson 2007). It becomes therefore feasible for firms to exert a kind of coercive governance mechanism to help local people or aid capital markets in order to adopt a responsible governing practice.

Discussions

Our findings show how firms in developing countries can manage various aspects of their institutional environment. Through a theory elaboration process (Lee 1999; Lawton et al. 2013), there is an opportunity to enhance a theoretical connection, not previously addressed between the literature on CSR and institutional theory. In particular, we contribute to the institutional theorisation of CSR by using the ‘weak institutional’ concept to show how private morality and the quest for social legitimacy are important motivating factors in the pursuit of responsible business practices in weak institutional contexts. These factors are not necessarily isolated, but are integrated and interactive. The case study highlighted key coping strategies adopted by Fidelity Bank to navigate through institutional voids in its pursuit of responsible business practices: democratisation for localisation, collaboration for impacts and institutional entrepreneurship.

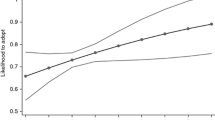

Although these findings may not be unique in isolation, they offer some novel insights in combination—especially in line with the focal research anchor of this study: how and why do firms in challenging and non-enabling institutional contexts pursue responsible business practices even where there are no incentives to do so? Based on insights from our case study, it could be argued that the underlying rationales for CSR, which are complementary, cumulatively constitute some form of CSR adaptive mechanisms necessary for coping with the challenges of weak institutional contexts. These complementary CSR adaptive mechanisms in turn inform the CSR strategies developed within these contexts. The successful outcomes of the strategies reinforce the adaptive mechanisms, such that the mechanisms and the strategies are locked in a continuous learning loop, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

As shown through our data (e.g. “We try to avoid the popular norm in Nigeria…”—CSR Manager), these CSR adaptive mechanisms shield the organisations from the influences of the challenging and non-enabling institutional context. In other words, the CSR adaptive mechanisms and the associated strategies jointly constitute a form of ‘institutional immunity’—i.e. “low sensitivity to a particular set of institutional influences that enables an organisation to deviate from institutional logics” (Lepoutre and Valente 2012, p. 287), which accounts for a firm’s non-conformity to the dominant norms and practices of its institutional context (e.g. “We don’t stop since someone doing the wrong thing is not a good enough reason for us to stop doing the right thing…”—focus group participant). The adaptive mechanisms constitute a layer of defence and filter between the organisation and its institutional context as illustrated in Fig. 3. Through this process, the firm creates a virtuous learning cycle—i.e. a form of double loop learning (Argyris 1982, 1985)—between its CSR strategies and rationales (e.g. lessons from the localisation of CSR decisions).

Comparing our findings to developed countries, we notice that the institutional complexity of our case places higher demands for self-governance, collaboration, institutional building and empowerment. Contrary to the postulations of Campbell (2007), we found that Fidelity Bank acts responsibly despite operating in a weak institutional context. We know from Martin (2003) that peer pressure also can push firms to behave more socially, but the peer pressure in this case was low (e.g. “If you don’t say thank you by doing CSR, nobody is going to kill you, and no one is going to say they won’t buy from you”—focus group respondent). We believe that self-regulation and values were substitutes here to replace the voids. Similar to Belal and Owen (2007), we did find CSR to be different relative to developed countries, as weak institutional conditions dictated the corporate behaviours for empowerment and collaboration.

In this regard, we contribute to the literature on CSR by fostering a better understanding of the corporate social activities in varying institutional contexts. We used theory elaboration process (Lee 1999) to identify, re-direct and re-connect institutional theory to explore CSR activities using two research questions—“why” and “how” firms can use CSR in countries with weak institutional conditions in two ways. We did this by presenting the implications to the broad literature on CSR and specifically to the budding literature on the institutional accounts of CSR (Matten and Moon 2008, p. 407) by conceptualising how CSR in developing economies is done given the often weak institutional contexts of these economies. Thus, the core of this paper is not only that CSR is possible in well-functioning market economies, but also that a better understanding of CSR in developing countries can be gained by discussing the boundary conditions of current CSR understandings and defining the preconditions of an ‘economic governance role of externalities’ that CSR should fill in, as well as creating the environment to encourage more institutional entrepreneurial efforts in promoting CSR.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we note that CSR practices in weak institutional contexts, where there are low incentives to internalise negative corporate externalities due to non-complementary institutional governance mechanisms, are more likely to be driven by normative values than instrumental motives. This runs contrary to the views of Aguilera et al. (2007, p. 848) who argued that “…for insider organizational actors…to be strongly motivated to engage in effective, strategically managed CSR initiatives, they will first need to see the instrumental value of these initiatives and, thus, will be acting from instrumental motives, followed by relational and then moral motives”. The main thesis of this paper is, however, that although CSR requires strong complementary institutions, which are not often present in most emerging/developing economies, firms such as Fidelity Bank, Nigeria are increasingly demonstrating entrepreneurial efforts in anchoring their CSR activities as a private governance of externalities, which are not captured due to the institutional void. This understanding is absent in the extant literature on CSR, which assumes that CSR cannot occur in this non-philanthropic manner in weak institutional contexts. Following this line of thinking and drawing inspiration from the European Commission (2011), we articulate CSR in developing countries (with weak institutional environments) as the voluntary reduction of negative corporate externalities and the commitment to enhance positive externalities by addressing social problems and filling institutional voids sustainably.

In terms of practice relevance, we anticipate that this study will help local firms in developing economies to adopt CSR strategies that fit with local and international institutional pressures on the one hand while on the other hand, global firms operating in developing economies can better appreciate the need to fill institutional voids using CSR as a governance tool. Some possible strategies have been highlighted. In particular, the discussions in this paper have important implications not only for CSR by local firms but also for the CSR practices of MNCs who inhabit both worlds of developed and developing economies. We acknowledge that MNCs are treated as if they are a homogenous group in the literature. Despite some shared organisational structures, values and practices, research data suggest that MNCs adhere to the norms of different varieties of capitalism (Hall and Soskice 2001) and are, therefore, shaped by different institutional configurations underpinned by different socio-economic ideologies (Amaeshi and Amao 2009). In the same way, also, their host countries exhibit different institutional arrangements, while some are welcoming, strong and vibrant, others are hostile, weak and fragile.

Building on Amaeshi et al. (2006), Adegbite et al. (2012), Azmat and Samaratunge (2009) and Blowfield and Frynas (2005), our study does consider that some local firms do compete nationally for customers (like Fidelity Bank), however, we also find that there was no competition for CSR initiatives in our context, as seen in other developed countries like the UK or USA. Moreover, some scholars may argue that firms in developed countries compete both on the ‘product/service market’ and the ‘CSR market’ (as shown on national rankings and CSR awards) across different sectors (McWilliams and Siegel 2001; Campbell 2007). However, we find that although CSR provides both an opportunity as shown in our emerging market organisation, it could have higher costs as moving towards developing CSR policies and initiatives comes with a price. More importantly, we appreciate institutional variances, however, CSR remained a national matter embedded in a national context with its own characteristics, and thus it was legitimate to examine the occurrence of the concept in this emerging market.

Directions for Future Research

We anticipate that our discussions would present a useful foundation upon which further research can be conducted in unpacking the institutional determinants of CSR in different capitalist systems. Future research should aim to advance ideas on what constitutes effective CSR programmes and initiatives specifically in developing countries, including the conditions that would make them effective.

As seen in many qualitative studies, a single case study method can have its limitations, especially by having a thin sample in terms of respondents, as it can make our model not generalizable for all international contexts. However, there is neither better/worse or even perfect way of doing CSR, nor is there a ‘CSR market’ in emerging markets. But from our case study, we do find evidence of how CSR unfolds in the Nigerian banking sector, and how it can influence the overall development of a CSR institution in the country and may even provide a blueprint through which other firms (similar) in emerging economies can benefit. Future research on CSR in other developing countries can test the applicability of these insights.

In addition, while CSR in Nigeria may be rooted in social legitimacy and relational motivations, due to the country’s largely collectivist culture (The Hofstede Centre 2013), this may not be true in all developing countries with weak institutional settings, especially where the culture is more individualistic. However, as the Hofstede’s dimensions illustrate, most developing countries are collectivist and CSR as explained by social legitimacy motivations is an applicable explanatory framework for CSR in many developing countries such as in sub-Saharan African and East Asia. This needs to be further investigated.

Given the multilevel and complex nature of CSR motives (Aguilera et al. 2007) and the enduring nature of CSR practices in most developing countries with weak institutions, future scholars may want to explore the “why” and “how” questions further. Although this study acknowledges that the rationales and strategies for CSR in weak institutional contexts could be linked in a re-enforcing manner—i.e. a form of double loop learning (Argyris 1982, 1985)—as schematically illustrated in Fig. 2 we have not explored in micro details how the drivers of CSR practices in weak institutional contexts translate to specific strategic choices revealed by our data. We suspect that these would involve intricate and complex processes, routines and mechanisms, and would require further attention in future empirical works. Understanding the interactions between the drivers of CSR and the strategic options will be a further contribution to the limited literature on CSR in weak institutional contexts.

Furthermore, future research can examine MNCs and their internal environment, including their organisational culture and leadership and how these shape CSR in challenging and non-enabling environments. MNCs have unique organisational capabilities, which are often taken for granted in the political economy of MNCs but could constitute a significant differentiating factor in the behaviour of an MNC in a host country (Alpay et al. 2005). Given these factorial differences and the inadequacies of existing international legal arrangements to properly regulate the global firms in transnational social spaces (Mattli and Woods 2009; Ruggie 2007), future studies should further aim to bring together the highlighted complex sources of influence on MNCs.

Notes

‘Western capitalist institutions’ is cautiously used here to signal the dominant views of capitalism—either liberal or coordinated market economies—which tend to reflect western views of capitalism and markets (see Varieties of Capitalism literature for instance—Hall and Soskice 2001). This view of western capitalist institutions, which has also informed some recent major works on CSR—e.g. Matten and Moon (2008), Campbell (2007), tends to be the yardstick for assessing the institutional conduciveness of CSR in non-western developing economies (e.g. Jamali and Neville 2011).

It is worthwhile to differentiate what we mean here by “challenging and non-enabling institutional contexts” from “controversial industry sectors”. The latter was a theme of a recent special issue of this Journal (Lindgreen et al. 2012). Although our “challenging and non-enabling institutional contexts” may share some common characteristics with “controversial industry sectors”—given that both would pose some challenges to the normal practice of CSR—in our case, the “national business system” (i.e. the business environment) (Whitley 1999; Matten and Moon 2008) is the source of the challenge and not necessarily the nature of the business of the firm or the sector, as in the special issue.

Institutional voids here represent situations where important institutional arrangements needed to support markets (often ‘western capitalist institutions’) are either absent or too weak to perform in the same manner as seen in developed western economies. However, institutional voids may further create an opportunity for substitution by other institutional arrangements or a deviation by outliers from the institutional normative constraint (Mair and Marti 2009; Lepoutre and Valente 2012).

Fidelity Bank Plc began operations in 1988 as a merchant bank and converted to commercial banking in 1999 before becoming a universal bank in February 2001; Fidelity Bank, today, is a result of the merger with the former FSB International Bank Plc and Manny Bank Plc in December 2005 (Fidelity Bank 2014). The bank maintains presence in the major cities and commercial centres of Nigeria and is reputed for integrity, professionalism, quality, stability of its management and staff training (Fidelity Bank 2014).

Some of the CSR activities of Fidelity Bank include the Creative Writing Workshop, the Fidelity Helping Hands Programme, as well as their several educational projects. Fidelity Bank has consistently won awards, both nationally and internationally, with these successful CSR programmes.

For more details see Aguinis and Glavas (2012).

It is important to note that the ‘black swan’ analogy (i.e. using the existence of one black swan to falsify the statement “All swans are white”) and the ‘logic of a situation’ are credited to Popper (1959, 1963) as justification for the use of single case studies in science. In addition, single case studies are recognised in the extant management literature as credible sources of insights (for more details see: Gibbert 2006; Gibbert et al. 2008; Gibbert and Ruigrok 2010).

Both interview respondents lead the CSR activities of the company and are responsible for its strategy formulation, in direct working relationship with the CEO.

The questioning guide followed during the interview and focus group discussions is provided in Appendix 1.

These include managing environmental and social risks in clients’ businesses; contributing to greenhouse emissions reduction; being guided by the International Bill on Human Rights; empowering and creating opportunities for women; timely reporting and transparent disclosures; collaborating with partners on CSR; leading by example in environmental and social footprints management; as well as doing good and doing well (Fidelity Bank 2014).

References

Adegbite, E. (2014). Good corporate governance in Nigeria: Antecedents, propositions and peculiarities. International Business Review,. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.08.004.

Adegbite, E., Amaeshi, K., & Amao, O. (2012). The politics of shareholder activism in Nigeria. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(3), 389–402.

Adegbite, E., Amaeshi, K., & Nakajima, C. (2013). Multiple influences on corporate governance practice in Nigeria: Agents, strategies and implications. International Business Review, 22, 524–538.

Adegbite, E., & Nakajima, C. (2011a). Corporate governance and responsibility in Nigeria. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 8(3), 252–271.

Adegbite, E., & Nakajima, C. (2011b). Institutional determinants of good corporate governance: The case of Nigeria. In E. Hutson, R. Sinkovics, & J. Berrill (Eds.), Firm-level internationalisation, regionalism and globalisation (pp. 379–396). Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Agger, A., & Löfgren, K. (2008). Democratic assessment of collaborative planning processes. Planning Theory, 7(2), 145–164.

Aguilera, R. V., & Jackson, G. (2003). The cross-national diversity of corporate governance: Dimensions and determinants. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 447–465.

Aguilera, R., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility—A multi-level theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 836–863.

Aguilera, R. V., Williams, C. A., Conley, J. M., & Rupp, D. E. (2006). Corporate governance and social responsibility: A comparative analysis of the UK and the US. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 14, 147–158.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38, 932–968.

Alpay, G., Bodur, M., Ener, H., & Talug, C. (2005). Comparing board-level governance at MNEs and local firms: Lessons from Turkey. Journal of International Management, 11, 67–86.

Amaeshi, K. (2009). Stakeholder management: A multi-level theorisation and implications for practice. In E. Chinyio & P. Olomolaiye (Eds.), Construction stakeholder management. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Amaeshi, K. (2010). Different markets for different folks: Exploring the challenges of mainstreaming responsible investment practices. Journal of Business Ethics, 1(92), 41–56.

Amaeshi, K., & Adi, A. B. C. (2007). Reconstructing the corporate social responsibility construct in Utlish. Business Ethics: A European Review, 16(1), 3–18.

Amaeshi, K., Adi, A. B. C., Ogbechie, C., & Amao, O. O. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in Nigeria: Western mimicry or indigenous influences? Journal of Corporate Citizenship (Winter Edition), 24, 83–99.

Amaeshi, K., & Amao, O. (2009). Corporate social responsibility in transnational spaces: Exploring the influences of varieties of capitalism on expressions of corporate codes of conduct in Nigeria. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(2), 225–239.

Amaeshi, K., Nnodim, P., & Osuji, O. (2008). Corporate social responsibility in supply chains of global brands: A boundaryless responsibility? Clarifications, Exceptions and Implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 1(81), 223–234.

Argyris, C. (1982). Reasoning, learning, and action: Individual and organizational. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Argyris, C. (1985). Strategy, change and defensive routines. New York: Harper Business.

Asongu, J. J. (2007). The history of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business and Public Policy, 1(2), 1–18.

Azmat, F., & Samaratunge, R. (2009). Responsible entrepreneurship in developing countries: Understanding the realities and complexities. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 437–452.

Bansal, P. (2003). From issues to actions: The importance of individual concerns and organizational values in responding to natural environmental issues. Organization Science, 14, 510–527.

Belal, A. R., & Owen, D. (2007). The views of corporate managers on the current state of, & future prospects for, social reporting in Bangladesh: An engagement based study. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 20(3), 472–494.

Blowfield, M., & Frynas, J. G. (2005). Setting new agendas: Critical perspectives on corporate social responsibility in the developing world. International Affairs, 81, 499–513.

Bondy, K. (2008). The paradox of power in CSR: A Case study on implementation. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(2), 307–323.

Bondy, K., & Starkey, K. (2014). The dilemmas of Internationalization: Corporate social responsibility in the multinational corporation. British Journal of Management, 25(1), 4–22.

Brammer, S., Jackson, G., & Matten, D. (2012). Corporate Social Responsibility and institutional theory: New perspectives on private governance. Socioeconomic Review, 10(1), 3–28.

Brown, D. L., & Woods, N. (2007). Making global self-regulation effective in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, J. L. (2007). Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 946–967.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39–48.

Child, J. (1972). Organizational structure, environment and performance: The role of strategic choice. Sociology, 6, 1–22.

CIA World Fact Book. (2012). CIA world fact book. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ni.html. Accessed 30 Aug 2012.

Chapple, W., & Moon, J. (2005). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Asia: A seven country study of CSR website reporting. Business and Society, 44(4), 415–441.

Cooper, D. J., & Morgan, W. (2008). Case study research in accounting. Accounting Horizons, 22(2), 159–178.

Crane, A. (2001). Corporate greening as amoralization. Organization Studies, 21(4), 673–696.

Crane, A., Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008). Corporations and citizenship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crouch, C. (2006). Modelling the firm in its market and organizational environment: Methodologies for studying corporate social responsibility. Organization Studies, 27(10), 1533–1551.

Deakin, S., & Whittaker, D. H. (2007). Re-embedding the corporation? Comparative perspectives on corporate governance, employment relations and corporate social responsibility. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(1), 1–4.

DiMaggio, P. J. (1988). Interest and agency in institutional theory. In L. G. Zucker (Ed.), Institutional patterns and organisations: Culture and environment (pp. 3–20). Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

Doh, J. P., & Guay, T. R. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 43, 47–73.

Dukerich, J. M., Nichols, M. L., Elm, D. R., & Vollarath, D. A. (1990). Moral reasoning in groups: Leaders make a difference. Human Relations, 43(5), 473–493.

Eggertsson, T. (2005). Imperfect institutions: Possibilities and limits of reform. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 4, 532–550.

European Commission. (2011). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A renewed EU strategy 2011–14 for Corporate Social Responsibility. Accessed September 19, 2014, from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0681:FIN:EN:PDF.

Eweje, G. (2006). The roles of MNEs in community development initiatives in developing countries. Business and Society, 45(2), 93–129.

Ewings, P., Powell, R., Barton, A., & Pritchard, C. (2008). Qualitative research methods. In E. Adegbite, K. Amaeshi, & O. Amao (Eds.), The politics of shareholder activism in Nigeria. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(3), 389–402.

Fidelity Bank. (2014). Corporate social responsibility. Fidelity Bank. Accessed March 3, 2014, from http://www.fidelitybankplc.com/csr.

Filatotchev, I., Jackson, G., Gospel, H., & Allcock, D. (2007). Key drivers of ‘good’ corporate governance and the appropriateness of UK policy responses. London: The Department of Trade and Industry.

Fineman, S., & Clarke, K. (1996). Green stakeholders: Industry interpretations and response. Cited in Amaeshi, K. (2009). Stakeholder Management: A multi-level theorisation and implications for practice. In E. Chinyio & P. Olomolaiye (Eds.), Construction stakeholder management. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Fligstein, N. (2001). Social skills and the theory of fields. Sociological Theory, 19, 105–125.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245.

Gallo, P. J., & Christensen, L. J. (2011). Firm size matters: An empirical investigation of organizational size and ownership on sustainability-related behaviors. Business and Society, 50, 315–349.

Gibbert, M. (2006). Muenchausen, black swans, and the RBV. Journal of Management Inquiry, 15(2), 145–151.

Gibbert, M., & Ruigrok, W. (2010). The “what” and “how” of case study rigor: Three strategies based on published work. Organizational Research Methods, 13, 710–737.

Gibbert, M., Ruigrok, W., & Wicki, B. (2008). What passes as a rigorous case study? Strategic Management Journal, 29, 1465–1474.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Gjolberg, M. (2009). The origin of corporate social responsibility: Global forces or national legacies? Socio-Economic Review, 7, 605–637.

Gladwin, T. N., Kennelly, J. J., & Krause, T.-S. (1995). Shifting paradigms for sustainable development: implications for management theory and research. Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 874–907.

Gobbels, M. (2002). Reframing corporate social responsibility: The contemporary conception of a fuzzy notion. In M. Van Marrewijk. (2003). Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: Between agency and communion. Journal of Business Ethics, 44, 95–105.

Graham, D., & Woods, N. (2006). Making corporate self-regulation effective in developing countries. World Development, 34(5), 868–883.

Habisch, A., Jonker, J., Wegner, M., & Schmidpeter, R. (2005). Corporate social responsibility across Europe. Berlin: Springer.

Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (Eds.). (2001). Varieties of capitalism—The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hamann, R., Agbazue, T., Kapelus, P., & Hein, A. (2005). Universalizing corporate social responsibility? South African challenges to the International Organization for Standardization’s new social responsibility standard. Business and Society Review, 110, 1–19.