Abstract

Hubris among CEOs is generally considered to be undesirable: researchers in finance and in management have documented its unwelcome effects and the media ascribe many corporate failings to CEO hubris. However, the literature fails to provide a precise definition of CEO hubris and is mostly silent on how to prevent it. We use work on hubris in the fields of mythology, psychology, and ethics to develop a framework defining CEO hubris. Our framework describes a set of beliefs and behaviors, both psycho-pathological and unethical in nature, which characterize the problematic relationship of the hubris-infected CEO towards his or her own self, others and the world at large. We then demonstrate how the development of authentic leadership may contribute to preventing or attenuating hubris by addressing its psycho-pathological nature through the true self and meaningful relationships with others. In addition to its psycho-pathological dimension, CEO hubris also contains an ethical dimension. We therefore propose that the development of the virtue of reverence might contribute to the prevention or attenuation of CEO hubris, because reverence makes the individual aware of his or her place in the world order and membership of the community of humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the early spring of 2002, Jean-Marie Messier, then CEO of Vivendi Universal, made several pronouncements expressing his supreme confidence in the future of the firm. On February 2nd, following an unprecedented fall in the firm’s share price, he stated: “We must understand that even though the market is always right, it is not right every day” (La Tribune 2002a). A month later, on March 6th, he proclaimed: “Vivendi is in better than good shape” (Libération 2002b). The context of these pronouncements was Vivendi posting astronomical losses of €14 billion for the fiscal year 2001. In July 2002, the Moody’s rating agency downgraded Vivendi’s debt to junk bond status and Jean-Marie Messier was forced to resign. The firm went on to post losses of €23 billion for 2002.

This now infamous example illustrates a phenomenon which is widely held to be responsible for various corporate failings—CEO hubris. Jean-Marie Messier, at the head of Vivendi Universal, overreached himself and the capacities of the firm—like Icarus, he tried to fly too high and the result was a disastrous fall. Research in management and finance has provided ample proof of the undesirable effects of CEO hubris. The media are also well aware of the issue and routinely attribute poor firm performance and various other troubles to CEO hubris. However, when we look into the management and finance literature to find an answer to the obvious question: “What is CEO hubris and how can it be prevented?”, we find that little attention has been paid to the topic. Existing research into the hubris phenomenon in the fields of finance and management is limited by the fact that it is not based on a precise definition of the concept, by an essentially static view and by the lack of credible alternatives which could provide ways to prevent or attenuate CEO hubris.

In order to address our research question, we leave the fields of management and finance and explore views of hubris among the powerful in other fields. We make three important assumptions which provide the basis for the development of a definition of CEO hubris. First, we posit that it exists only in a context of power. Second, we focus our analysis on the individual top executive, and more precisely the CEO, who wields the most power in an organization. Third, following Ciulla (1995) and Woodruff (2005), we posit that a leader can only be moral and that an individual in a position of power who displays unethical behaviors is therefore no leader, but can be qualified as a tyrant. We build on work in mythology (which is implicitly referenced in work in finance and management), in psychology and in philosophical ethics. By drawing on characterizations of hubris in these fields, we are able to put forward a framework depicting top executive hubris. We define hubris as containing both cognitive and behavioral aspects covering three dimensions. First, the hubristic CEO has a grandiose sense of self. Second, he or she considers him or herself to be above the community of humans. Finally, he or she does not feel constrained by the normal rules and laws, considering him or herself to be above them.

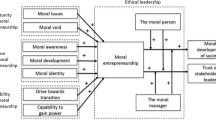

Making suggestions on how to prevent or attenuate CEO hubris is a real challenge, not least because, as our framework depicting CEO hubris shows, any suggested remedy needs to address both its psycho-pathological and ethical aspects. We put forward two theoretical contributions whose development would, taken together, address the three dimensions of CEO hubris (a grandiose self, disrespectful attitudes towards others and a misperception of one’s place in the world) in both their pathological and unethical manifestations. First, authentic leadership (Avolio and Gardner 2005; Walumbwa et al. 2008), through its reliance on the true self and insistence on meaningful and trusting relationships with followers, contributes to reducing the grandiose sense of self and reminds the CEO of his or her place in the community of humans. However, the moral aspect of authentic leadership is not entirely established and is still the subject of debate. We therefore believe that authentic leadership, while able to attenuate the pathological aspects of CEO hubris, is less qualified to deal with the moral aspects. Drawing on work in philosophical ethics, we put forward the idea of the virtue of reverence (Woodruff 2001, 2005) as a way to attenuate the vice of hubris. Reverence implies being conscious of the existence of some sort of transcendent order, which reminds the hubristic CEO of his or her own humanity. It also develops in his or her relationships with others and contributes to an awareness of his or her place in the human community. It therefore provides an ethical aspect to the prevention or attenuation of CEO hubris. Our paper makes four main contributions to our understanding of top executive hubris and its prevention at the theoretical level. First, we provide a detailed yet concrete framework defining CEO hubris for use in the fields of finance and management. Second, we establish the relevance of authentic leadership for work in the field of strategic leadership. Third, we contribute to the virtue ethics approach by emphasizing the relevance of one particular virtue for CEOs. Finally, we rely on a multidisciplinary approach which is more respectful of the reality and the complexity of CEO psychology.

Defining Top Executive Hubris

In this section, we assume that hubris is a phenomenon which affects those who hold power. We aim to provide a definition for the field of management of what hubris actually is. A review of existing research in management and finance pinpoints the limits of this literature, which provides ample evidence for the effects of CEO hubris but fails to define its real nature and is therefore insufficient as a starting point for understanding how it might be prevented or attenuated. We turn to work in other fields, namely mythology, psychology, and ethics, in order to develop a conceptual definition. We draw up a framework characterizing the key components of CEO hubris with reference to the individual’s relation to his or her own self, to others and to the world at large.

In Management: The Undesirable Outcomes of Hubris

Researchers in management and finance view hubris as a negative characteristic which can be used to explain negative outcomes for the firm. The analysis of the effects of hubris in management and finance dates back to Roll (1986), who puts forward the hypothesis that CEO hubris is a way to explain the otherwise unfathomable losses to acquiring firm shareholders which materialize on the announcement of a merger or an acquisition. The hubris hypothesis reconciles the paradox of value-destroying acquisitions—if the markets can see that a deal is undesirable, why do managers persist in making bids? Roll (1986) posits that a hubris-infected acquiring CEO is likely to overestimate the value of the combined entity. This will cause him or her to bid too high for a target and, through the operation of the well-documented “winner’s curse” effect, win the takeover contest. The markets, recognizing the price to be too high, react negatively and there is a corresponding fall in the market value of the acquiring firm and an increase in the value of the target firm—the acquiring CEO’s hubris causes a transfer of wealth from acquirer to target shareholders.

Subsequently, researchers in management and finance have both tested the predictions of the hubris hypothesis directly and linked hubristic tendencies among CEOs to other firm characteristics and outcomes. In most of these studies, however, researchers have run up against the problem of operationalizing CEO hubris, as there is no commonly accepted definition or scale of measurement. They have therefore used related concepts, such as narcissism and overconfidence, to proxy for hubris in their studies. In the mergers and acquisitions context, Hayward and Hambrick (1997) show that hubris-infected acquiring CEOs offer higher bid premiums for targets, and that the post-acquisition performance of their firms is worse than that of the firms of their non-hubristic counterparts. Malmendier and Tate (2008) proxy for hubris using the cognitive bias of overconfidence. They show that overconfident CEOs make more acquisitions than non-overconfident CEOs, and that the markets react less favorably to these acquisitions. The propensity to acquire is examined by Chatterjee and Hambrick (2007) in the context of CEO narcissism. The authors demonstrate that narcissistic CEOs are more likely to engage in acquisitions.

Some other studies document the performance effects of hubristic tendencies. Higher levels of CEO narcissism are linked to more extreme and more volatile firm performance (Chatterjee and Hambrick 2007). Others show how firm financing decisions are affected by the hubristic tendencies of the CEO. Malmendier and Tate (2005) show that investment by firms with overconfident CEOs is more sensitive to cash-flow than that of their non-overconfident counterparts. The rationale behind this result is that overconfident CEOs tend to believe that their firms are undervalued by the markets. They are therefore reluctant to go to the equity markets to fulfill their financing needs and instead rely on other sources of financing, notably cash. These findings are consistent with the fact that that firms run by overconfident CEOs prefer debt to equity (Malmendier and Tate 2011) and make lower dividend payouts (Desmukh et al. 2010). Finally, firms’ strategic decisions are affected by the hubristic tendencies of the CEO. In results on CEO hubris, narcissism and overconfidence, respectively, firms run by CEOs with these tendencies engage in more risk taking than other firms (Li and Tang 2010), show greater strategic dynamism (Chatterjee and Hambrick 2007) and invest more heavily in research and development (Hirshleifer et al. 2010).

The studies cited above provide clear evidence for the effects of CEO hubris and more specifically its undesirable outcomes. The finding that hubristic tendencies in a CEO entail negative or non-optimal outcomes for the organization is highly relevant to interested parties in the business community, such as investors, lenders, regulatory authorities and competitors. The effects captured are economically significant: for example, Hayward and Hambrick (1997) show that the most hubristic CEOs in their sample pay bid premiums which are on average 4.8% higher than those paid by the least hubristic. Likewise, Malmendier and Tate (2008) find that overconfident CEOs destroy, on average, $7.7 m more per acquisition than their non-overconfidence counterparts. The business press is also preoccupied with the issue of the hubris of corporate managers. A Factiva search for the term “hubris” in the English-speaking business press over the previous 2 years, carried out in February 2011, identified 1,118 articles in which ceo hubris was portrayed as an explanatory factor in, among others, bank failures during the recent financial crisis, poor performance, industrial accidents and various other corporate failings.

While the studies convincingly describe the undesirable effects of hubris, they fail to address some important issues. First, not only do the studies cited fail to provide a definition of hubris, they also proxy hubris by other psychological concepts such as overconfidence or narcissism, raising the question as to whether and how the concepts are related and what the distinguishing features of executive hubris might be. In addition, existing research fails to address such crucial questions as, for example, whether it is essentially cognitive or behavioral in nature. Second, existing studies provide an incomplete exploration of the effects of CEO hubris in that they only examine its negative side. While hubris, whatever its real nature, can certainly be viewed as a negative characteristic, this should not blind us to the possibility that positive effects may exist, such as those described in the context of narcissistic CEOs (Maccoby 2000; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006). Third, studies in management and finance do not discuss the causes of CEO hubris and how it develops through time. This essentially static view of hubris provides little or no scope for understanding when and how preventive or remedial action might be undertaken. Fourth, existing studies do not provide an alternative to hubris and fail to address the question of the ethics of the executive or of the organization. In this view, hubris appears to be an inescapable fate in which the hubristic executive is deprived of choice and condemned to destroy value. There is no allowance the possibility that things can improve, either through the actions of the CEO him- or herself or through the encouragement of a sympathetic entourage. Finally, research in finance and management is reductive of CEO psychology, as in many cases it is seen as essentially binary (hubristic vs. non-hubristic) and provides a simple snapshot rather than a dynamic view. The limits we have identified lead us to examine the views of hubris developed in other disciplines and which will enable us to better understand its essential nature.

In Mythology: The Tragedy of Hubris

As a starting point in our development of a definition of hubris, we first look back to the origins of hubris in Greek mythology. Much of the work on hubris carried out in management and in finance refers implicitly to Greek myth but does not examine the implications of this, although they are important to our understanding of the nature of hubris. The first references to hubris appear in the myths relating the rise and fall of various heroes in different Greek tragedies. Hubris describes a sense of overweening pride, a defiance of the gods, which was then punished through the intervention of Nemesis, who wrought various forms of death and destruction on the hubristic hero and the general population. The Ancient Greek view of hubris is not limited to beliefs, it also implies behaviors: it “is not only an attitude, it is a kind of action as well” (Woodruff 2005, p. 15). Among many examples, we can cite the case of Oedipus, who killed his own father after pronouncing that “he acknowledged no betters except the gods and his own parents” (Graves 1985, p. 128). His Nemesis came in the form of the death of his father and later, his mother’s suicide, his own blindness and a plague on Thebes. Likewise, Creon placed himself above the law when he defied the customs of the day by forbidding the burial of his dead enemies after his defeat of the Argives. This one act caused Theseus to attack Creon and to imprison him, and ultimately led to the death of Haemon and Antigone.

The myth of Icarus seems to be of particular relevance to the issue of CEO hubris. In the version of the myth told by Graves (1985), Icarus was exiled to the Island of Crete with his father Daedelus. Daedelus had the ingenious idea of making artificial wings for both himself and his son so that they could fly away from the island. Before setting out, he instructed Icarus to fly neither too low nor too high. As the pair flew away, they were taken to be gods by watching fishermen, shepherds, and ploughmen, and Icarus came to believe in his god-like status. “Rejoiced by the lift of his great sweeping wings” (p. 100), he flew too close to the sun, the wax on his wings melted, and he fell to his death in the sea. Although Icarus was not himself a leader, the myth has been used to illustrate cycles of hubris and nemesis among America’s political leaders (Beinart 2010). There are two important aspects to the myth of Icarus which make it relevant to the case of leaders in general and more specifically to CEOs. First, as the onlookers ascribed god-like qualities to the soaring figures of Daedelus and Icarus, so society has created a romantic view of business leadership (Meindl et al. 1985). We attribute control over the organization’s fate to the CEO, who thereby becomes a type of popular hero. As a result, CEOs may begin to believe in their own heroic importance and demand high levels of compensation and perks, which we grant them due to our acceptance of the myth (Conger 2005). Second, Deadelus exhorted his son to fly neither too high nor too low, but to keep in the safe middle zone where he would not be pulled down by the water or burned by the sun.Footnote 1 CEOs are “special” in the sense that they are mandated to lead and to take responsibilities. This requires that they sometimes act in ways which are different to those which would be acceptable in others—so they should not act like everyone else. However, they should also avoid falling prey to hubris, which can cause them to fly too high and damage the organization. Our aim in this paper is to understand how we can encourage CEOs to fly at the right height, which implies both taking the responsibilities which fall upon them as business leaders and avoiding the excesses which a position of power can trigger.

In Psychology: Hubris as a Personality Disorder

Work in the field of psychology has recently attempted to transform the notion of mythical hubris into a psychological concept which describes an ego-pathology. Owen and Davidson (2009) put forward the concept of hubris syndrome as a way to characterize a particular personality disorder which is specific to individuals in a position of power. Hubris syndrome is more than just an extreme case of other pathologies such as narcissism. It is an acquired condition, as it is triggered by accession to a position of power and the resulting lack of constraints on the individual’s behavior. The syndrome consists of fourteen criteria, displayed in Table 1, and a diagnosis of hubris syndrome is made if a leader exhibits at least three of the criteria, of which at least one unique feature. Hubris syndrome overlaps considerably with narcissism, as seven items out of the 14 are included in the diagnostic criteria for narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) (American Psychiatric Association 1994). Two other criteria overlap with antisocial personality disorder and histrionic personality disorder. The remaining five items are, however, unique to hubris syndrome.

The hubris syndrome items are a combination of both attitudes and behaviors. If we focus only on the items which are unique to hubris syndrome, and which therefore characterize the aspects it contains in addition to those which overlap with other personality disorders, we find some items which describe cognitions and others which describe behaviors. Items 5 and 10 describe an individual’s identification with the organization and his/her assumption that he/she is above the law, while items 6 and 12 describe behaviors that result from the various beliefs held by the hubristic individual. Item 13 characterizes both an attitude (‘broad vision’) with the consequent action (or in this case inaction, as the individual neglects practical considerations when making a decision).

The case studies presented by Owen and Davidson (2009) examine evidence of hubris syndrome among post-war UK and US prime ministers and presidents. However, the authors state explicitly that hubris syndrome also applies to business leaders, as evidenced by the behaviors and attitudes of some financial sector CEOs during the 2008 crisis. The clinical pattern of hubris syndrome put forward by Owen and Davidson (2009) contributes to our understanding of hubris among CEOs as it provides a clear description of the specific context of power, which triggers the condition, and it underlines the existence of both cognitive and behavioral dimensions.

In Ethics: Hubris, the Vice of the Tyrant

Another highly relevant approach to hubris is provided by philosophers in the field of ethics, although this stream of literature has been largely disregarded by researchers in management and in finance. In ethics, hubris is characterized as the vice of the tyrant. In this view, which is first developed in Ancient Greek texts, a leader cannot be hubristic, because in that case he or she ceases to be a leader and is qualified as a tyrant: “Leadership (as opposed to tyranny) happens only where there is virtue” (Woodruff 2005, p. 165). Commenting on Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus, both Winnington-Ingram (1971) and Scodel (1982) demonstrate that hubris-infected individuals in a position of power are tyrants. The rule of a tyrant is reliant on fear. The actions of notorious twentieth century tyrants, such as Hitler, Stalin, and Hussein, were punctuated by episodes of extreme cruelty both towards their so-called allies or supporters and towards large sections of the civilian population (Glad 2004). The tyrant displays a certain number of typical attitudes which then may lead him or her to engage in specific behaviors. Tyrants are convinced of their uniqueness and consider themselves to be above the normal rule of the law (Woodruff 2005). At the same time, they are also unsure of themselves and lack real self-confidence (Glad 2004). These attitudes cause them to reject any advice or criticism and to refuse to take responsibility for their own actions (Woodruff 2005), preferring instead to silence their critics or to blame others for reversals or misfortunes (Glad 2004). While Glad (2004) concentrates on political tyranny, the concept has also been applied in the business setting. Tyrants at the head of corporations “may behave in accordance with the goals, tasks, missions and strategies of the organization, but they typically obtain results not through, but at the cost of, subordinates” (Einarsen et al. 2007, p. 212). Ma et al. (2004) emphasize the refusal of tyrants to brook any opposition and their tendency to rule by fear.

While the snapshot of the tyrant provided above gives insights into the individual aspects or manifestations of hubris, there are also situational aspects which favor the emergence of hubris. For Winnington-Ingram (1971), it is accession to a position of power which is the starting point for hubris: “It is thus a small step to say that kingship engenders hubris, glutting it with many things – wealth, doubtless also the power which depends on wealth” (p. 126). In Scodel’s (1982) reading of Oedipus Tyrannus, hubris in the powerful is engendered by a specific type of society. In a first stage, monarchy appears if law and justice are no longer present among the population. This results in a second stage in which civil strife leads to the triumph of the most hubristic member of the population, who then becomes a tyrant. Parallels can be drawn between the current economic and business system and the causes of hubris discussed above. Mattéi (2009), in a discussion of the work of Hannah Arendt, explains that modern societies are process based, meaning that actors are locked into an endless cycle which has no moral limits and even devalues any reason which does not serve the process. This sentiment is echoed in Solomon (2003): “corporate managers and employees feel obliged and committed to act in conformity with corporate pressures and policies even when they are questionable or unethical, and they learn to rationalize accordingly” (p. 52). In an analysis of the impact of psychology on the current economic system, Akerlof and Shiller (2009) point out that the pressures of the system itself require checks and balances to limit CEO behavior: “… it is precisely because there are these CEOs, so unapologetic about making a buck for themselves and for their companies, that there is a need for a counterbalance, to ensure that all of this energy does not spill over into dishonesty” (p. 29). To sum up, we can say that political and/or economic systems contribute, over and above the characteristics of the individual, to the creation of hubristic top managers. This is not to suggest, however, that hubris and the resulting tyranny are the only possible outcomes when an individual accedes to a position of power, as to do so would imply an overly pessimistic view of the executive population and would limit the analysis of hubris among top managers to a simple discussion of how best to limit its excesses. Rather, we feel that accession to a position of power can lead to either a good or bad outcome. Either the individual develops the virtues or behaviors required to become a leader, or he/she falls into the trap of the vice of hubris and turns into a tyrant.

Top Executive Hubris: A Framework

Our analysis of CEO hubris, which draws on work in different fields, leads us to put forward a framework describing the specific nature of hubris which is relevant to the business context (see Table 2). An overarching conclusion we draw from our analysis is that CEO hubris is only present in a context of power and, further, our characterization of top executive hubris is detailed into beliefs and behaviors revolving around three different aspects: the relation with the self, with others and with the world.

First, Hubris implies a grandiose sense of self, which is translated into actions such as the use of the royal “we”, speeches peppered with superlatives and exaggeration and expressions of overarching ambition. Pronouncements made by the former CEO of Vivendi Universal, Jean-Marie Messier, provide an example of this type of behavior: “one of my colleagues makes fun of me by saying ‘he’d like to be the first boss to be canonized’ […] I must say that if the capitalist model provided for such a form of recognition, I might be tempted to apply!” (Messier 2000). Pronouncements made by Jimmy Cayne, former CEO of the now defunct Bear Stearns, also illustrate this tendency to exaggerated boasting: [to Alan Greenberg, then CEO of the bank, during a job interview, on his skills as a bridge player] “Mr Greenberg, if you study bridge the rest of your life, if you play with the best partners and achieve your potential, you will never play bridge like I play bridge” (Cohan 2009, p. 199). In addition, hubristic CEOs consider themselves to be uniquely qualified for the position they hold, which leads them to resist attempts to get them to leave the firm. For example, after his resignation in 2006, the former CEO of Vinci, Antoine Zacharias, sued the firm for forcing him to resign and claimed a huge sum in compensation. The court dismissed his request. In spite of their high opinion of their own qualifications, CEOs affected by hubris are afraid of being replaced. This causes them to put in place entrenchment strategies in the manner described in Shleifer and Vishny (1989). One such example is provided by Antoine Zacharias, who secured his power base by totally renewing the compensation committee after it refused to change the rules on his pay (The Daily Telegraph, 2010).

In their relationships with others, hubristic CEOs consider themselves to be above the community of humans. This causes them to disrespect people, to manage by fear and refuse to accept advice or criticism. In the case of Jimmy Cayne, this lead him to give himself preferential treatment (“He, alone, authorized himself to smoke inside the building”; Cohan 2009, p. 173) and, more disturbingly, to resort to physical intimidation when on the defensive (Gladwell 2009). Jean-Marie Messier was unable to accept the reality of the situation of Vivendi, of which he was CEO from 1994 to 2002. He felt confident in asserting that “Vivendi is in better than good shape”, despite the group posting €30 billion of debt (Johnson and Orange 2003).

Those in positions of power who are infected with hubris not only believe themselves to be above the community of humans, but also above the laws of the gods, or the natural or social orders, including laws and the economy. This causes them to commit fraud or to manipulate the rules or the law to attempt to bend them to their own ends. An example of this type of behavior is that of Antoine Zacharias, who dominated the governance structures of Vinci with impunity, until he was finally sentenced by a French court for “abuse of power” in the conditions under which he had prepared his retirement (Libération, 2011). Such CEOs may consider themselves and their firms to be above the law of the markets, as evidenced by pronouncements made by Jean-Marie Messier (“We must understand that even though the market is always right, it is not right every day”; La Tribune 2002a) or Jimmy Cayne (“So you have to ask yourself, What can we do better? And I just can’t decide what that might be…. Everyone says that when the markets turn around, we will suffer. But let me tell you, we are going to surprise some people this time around. Bear Stearns is a great place to be”; Gladwell 2009, pp. 4–5).

Our framework describing hubris among top executives is deliberately centered on the individual. This is not to deny that there may be social expectations or an organizational context which aggravate or attenuate hubris, but rather to explore what interests us the most, which is to identify the qualities and virtues top executives and business organizations should promote to provide good leadership.

The framework highlights three important features of executive hubris. First, it identifies difficulties in the individual’s relationship with his or her own self, with others and with the world at large. Second, it characterizes a mix of both cognitive aspects and behaviors. Third, it shows that top executive hubris contains certain aspects which go over and above those which make up other psychological concepts such as narcissism and overconfidence. Hubris is specific to a context of power, while definitions of both overconfidence and narcissism are applied to the general population and are not context-specific. In addition, hubris implies that the individual assimilates him- or herself with the power which is vested in him or her, as in the famous statement by the king of France, Louis XIV: “L’Etat, c’est moi”. This aspect is absent from narcissism and overconfidence, even if narcissists may mistake what constitutes self-interest for the interests of others. Further, overconfidence describes a cognitive bias but does not predict a specific pattern of behavior. It characterizes a tendency to overestimation but not to assimilation of the self with the position held. Finally, narcissists are essentially conformist and seek to comply with expectations, rules and laws (Haubold 2006), while hubris implies a total disregard for these.

An additional important feature of our framework defining CEO hubris is that it does not just describe a psycho-pathology, but also characterizes unethical behaviors and attitudes. While the dimension of hubris which involves the self can be considered in terms of psycho-pathology, this is insufficient to grasp the full implications of the other dimensions, which describe the individual’s problematic relationship to others and the world at large, and therefore contain an ethical dimension.

Preventing Hubris Among Top Executives

Qualities protective against disproportionate hubris, like humour and cynicism are worth mentioning. But nothing can replace the need for self-control, the preservation of modesty while in power, the ability to be laughed at, and the ability to listen to those who are in a position to advise. Another important safeguard comes from the practice of devoted concern to the needs of individuals and not simply to the greater cause.

(Owen and Davidson 2009, pp. 1404–1405).

As emphasized previously, existing literature has not only failed to define top executive hubris, but also avoided some important issues such as the antecedents of hubris or its development over the long term. These issues are, however, of paramount importance for those (scholars, practitioners, or business leaders) who would like to know how to prevent hubris among top executives and develop moral leaders at the top. Using our framework for top executive hubris as a basis, we explore potential factors and seek to answer the question: What can be done by a CEO, in this particular context of top executive power, to avoid hubris in its pathological as well as its unethical behaviors?

In the previous section, we emphasize that top executive hubris implies problems with the self and with the relationship of the individual to both others and the wider world which will all have to be taken into account by the proposed solutions. We also define hubris as a combination of pathological and unethical attitudes and behaviors. In this section, we discuss the relevance of two theoretical contributions, from psychology and from ethics, which could address the three dimensions of hubris, and therefore help us to understand how to prevent hubris at the top as well as providing top executives with guidelines on how to cultivate moral leadership. The two contributions are both highly relevant to a discussion of leadership and to that extent can be considered as part of the leadership ethics corpus. The first one is authentic leadership development (as defined by the Authentic Leadership Theory; Avolio and Gardner 2005; Walumbwa et al. 2008), which looks at power through a psychological lens: it focuses on the nature and the role played by the quest for a true self in leadership development, and also considers how an authentic leader contributes to the development of authentic followers. The second one is reverence (as defined by Woodruff 2001, 2005) which derives from a philosophical and virtue ethics approach: it focuses on the importance of the virtue of reverence in the leader’s relationships with others and the world at large. Taken together, they offer a complete view of what a CEO could place on his or her leadership agenda to avoid hubris in is pathological and unethical forms.

Developing Authentic Leadership

As described above, hubris implies the inflation of the ego and the development of a false and grandiose self. It therefore follows that for a top executive to avoid hubris and develop true leadership, he or she will have to discipline his or her self by keeping his or her ego in check and by staying connected to his or her true self. In addition, CEO hubris implies a problematic relationship with others, which is also addressed by authentic leadership (Avolio and Gardner 2005; Walumbwa et al. 2008), as the latter encourages the creation of authentic relationships.

In the following section, we suggest how the development of authentic leadership, which is based on the quest for one’s true self and the development of authentic relationships with followers, could serve as a practical model for leadership development, particularly in the top executive context in which power brings the risk of hubris.

Authentic Leadership

While authenticity, like leadership, is an ancient concept that has been considered by both Greek and existentialist (Sartre 1984) philosophers and humanist psychologists (Rogers 1963; Maslow 1968, 1971), the development of an ‘authentic leadership’ model in the field of management is a relatively recent phenomenon (Luthans and Avolio 2003; Gardner et al. 2005; Walumbwa et al. 2008). The positioning of the Authentic Leadership Theory (ALT) in relation to other leadership theories or models is both original and ambitious. Its authors present it as “the root construct of all positive, effective forms of leadership (…) that transcends other theories and helps to inform them in terms of what is and is not “genuinely” good leadership” (Gardner et al. 2005, p. xxii). ALT itself emerged in 2003 (Luthans and Avolio 2003) and has been considerably developed since 2005. Walumbwa et al. (2008) put forward a refined definition of authentic leadership as “a pattern of leader behavior that draws upon and promotes both positive psychological capacities and a positive ethical climate, to foster greater self-awareness, an internalized moral perspective, balanced processing of information, and relational transparency on the part of the leaders working with followers, fostering positive self-development” (p. 94). This definition builds on the definitions of authenticity put forward by Harter as “owning one’s personal experiences, be they thoughts, emotions, needs, preferences, or beliefs, processes which are captured by the injunction to know oneself and behaving in accordance with the true self” (Harter 2002, p. 382) and by Kernis (2003) as “the unobstructed operation of one’s true, or core, self in one’s daily enterprise” (Kernis 2003, p. 13). The notion of self and the idea of a true self are therefore fundamental to the definition of authentic leadership.

The Authentic Leader

ALT describes the authentic leader through four behavioral dimensions: self-awareness, balanced processing, moral action, and relational transparency (Walumbwa et al. 2008) and within the framework of Authentic Leadership which encompasses the authentic leader, authentic followership, and an authentic organization.

First, authentic leaders are self-aware and driven by the need to comprehend and to connect with their true self. They are individuals who seek to understand their strengths and weaknesses, as well as their values, or their roles. They have a high level of self-confidence (but they are not overconfident) and unhesitatingly question themselves in a permanent effort to understand who they really are. Second, authentic leaders display balanced processing of information. They show objectivity and balance in their perception and internal management of information. They can therefore interpret a situation while avoiding the pitfalls of self-denial, distortion, or exaggeration. Their perception is not biased by defensive ego-protecting mechanisms. They constantly take feedback into account and seek to learn from their experience. Third, authentic leaders undertake moral actions. They behave in accordance with what they know of their own capacities and of the situation in which they find themselves. Their action is not motivated by a desire for reward, to avoid punishment or to give pleasure to others, but on the contrary comes from the search for coherence—a desire to align what they do with who they are. This self-regulation process is guided by internal moral standards and positive values. Fourth, authentic leaders cultivate relational transparency, i.e., openness and a reassuring proximity in their relations with others, especially with their followers. They instill in their teams a similar dynamic process of self-knowledge and self-regulation, thereby establishing authentic relationships with those around them. Contrary to the authentic leader, the hubris-infected tyrant loses contact with his or her true self and develops a self which is both grandiose and false. In addition, this self is neither grounded nor bounded by limits. The tyrant does not seek to align his or her acts with who he or she really is, but to align the world or others with what the he or she thinks he or she is or would like to be. He or she does not strive to learn or discover something true about him or herself or others, but to maintain the illusions he or she holds about the self and power.

The relationship that links a leader to his or her followers is characterized by a high level of trust, commitment, and considerable well-being within staff teams. In their paper explicitly entitled ‘A Self-Based Model of Authentic Leader and Follower Development’, Gardner et al. (2005) emphasize that the development of authentic leadership requires the parallel development of authentic followership: “however, authentic leadership extends beyond the authenticity of the leader as a person to encompass authentic relations with followers and associates. These relationships are characterized by: a) transparency, openness and trust, b) guidance toward worthy objectives, and c) an emphasis on follower development” (Gardner et al. 2005, p. 345). Relations between authentic leaders and their authentic followers are also characterized by the nature of the former’s responsibility towards the latter. The authors stress that the main purpose of authentic leaders is to authentically develop their followers, which distinguishes them for example from transformational leaders, who obtain the adherence of their followers based on their personality and the mission they propose. Authentic followership therefore contains the same four dimensions as authentic leadership.

In contrast to the authentic leader, hubris-infected tyrants’ relationships with their teams are based on fear, irresponsibility and sometimes intimidation and violence. Others do not receive recognition as individuals but are instrumentalized so as to hold up the mirror of flattery to the tyrant. The tyrant’s dream is to be free to build a world and relationships which reflect his or her grandiose image and which advance his or her entrenchment and power.

Scholars of leadership studies also highlight that the development of authentic leadership can only occur in an organizational context that is supportive, i.e., authentic organizations that “provide open access to information, resources, support, and equal opportunity for everyone to learn and develop, will empower and enable leaders and their associates to accomplish their work more effectively” (Avolio and Gardner 2005, p. 327). This description clearly contrasts to the context of tyranny dominated by fear and dissimulation, with results obtained at the cost of employees.

Finally, it is only the combination of authentic leaders, followers and organizations that will support the various positive outcomes of authentic leadership development. Gardner et al. (2005) suggest that authentic leadership encourages trust, commitment and well-being among followers in the workplace, and thereby increases the duration and authenticity of their performance. Walumbwa et al. (2008) compare the model of authentic leadership with two other models, transformational and ethical leadership, with which it shares certain characteristics. The results show that there is a positive correlation between the three types of leadership, which suggests that authentic leadership might have the same positive effects as those previously demonstrated in the two other types, i.e., organizational citizenship, organizational commitment, and follower satisfaction. These results are confirmed and enlarged upon in a third study, which demonstrates the positive effect of authentic leadership on follower job satisfaction and individual job performance. They contrast clearly with the results of research in finance and management, in which hubris in CEOs is clearly undesirable as it causes them take poor financial and strategic decisions.

How Can Authentic Leadership Development Prevent Hubristic Tendencies?

If we compare the authentic leader and the hubris-infected tyrant, it is clear that the two are diametrically opposite. By definition, hubristic CEOs have low levels of self-awareness. Unbiased processing of information is unlikely to be possible for a hubris-infected individual due to the distorted sense of his or her place in the world. It appears impossible for a hubris-infected CEO to display authentic behavior, in the sense that he or she will tend to engage in behavior which reinforces self-image. Finally, hubristic CEOs believe themselves to be above others in the community, which appears incompatible with the development of a trusting and open relationship with followers. We therefore suggest that investment by top executives in an authentic leadership development process could help them to avoid hubris. This suggestion relies on two arguments:

First, by developing an authentic leadership, the CEO is protected from the grandiosity and the fabrication of a false self which are implied by the first dimension of the hubris framework. The link between authentic leadership and hubris hinges on the concept of self. The self in this context refers to self-knowledge, as in the social psychology tradition, but a broader definition is also possible: “A full understanding of self encompasses the physical body, the socially defined identity (including roles and relationships), the personality, and the person’s knowledge about self (i.e. the self-concept). Self is also understood as the active agent who makes decisions and initiates actions.” (Baumeister 2004, p. 497). Studies in authenticity and ALT are grounded in the idea of the self and especially the process of development, integration and self-realization as understood by Maslow (1968, 1971) and Rogers (1963). Authenticity is represented as an ongoing individual process that integrates two major spheres: self-knowledge (i.e., owning oneself) and self-regulation in accordance with the true self that we endeavor to come to know (acting in accordance with one’s true self). While ALT builds on what we will call the “discipline of the true self”, hubris implies a loss of contact with the true self and sometimes the building of a false self: a phenomenon that Kets de Vries (1994) calls the “false-self syndrome” and that he observes in some top executives. According to Winnicott (1960), the false self is the expression of a rigid ego and is a defense mechanism to protect the true self which is perceived as fragile or threatening. The problem arises from the fact that behaviors are not linked to the true self, so the individual may experience feelings of emptiness, lack of meaning and even develop a split personality. Those who have developed these “as if personalities” experience difficulties in connecting to others and forming meaningful relationships. From this standpoint, the hubristic CEO appears to be someone who (for reasons linked to the individual and/or his or her environment) is somewhat fearful of introspection and the possible exposure of his or her weaknesses. He or she will therefore avoid looking inside him or herself, and will expend effort in constructing an image which can be presented to the outside world. The image is disconnected from the true self, but is consistent with the individual’s grandiose requirements. In contrast to those CEOs who are only affected by narcissism, the hubris-infected CEO sees his or her grandiose project right through to the end, without any fear of the disapproval or retaliation of others, or of punishment through the law.

Second, the development of the true self in authentic leadership goes hand in hand with the creation of meaningful and trusting relationships with others: “authentic leadership development involves ongoing processes whereby leaders and followers gain self-awareness and establish open, transparent, trusting and genuine relationships” (Avolio and Gardner 2005, p. 322). In contrast, the hubristic CEO does not consider the interests of anyone but him or herself, believing him- or herself to be above others. This leads him or her to manage through fear, violence or intimidation and to refuse advice or criticism.

What Authentic Leadership Development Cannot Prevent

As described above, we propose that authentic leadership development, as described by Avolio and Gardner (2005), insofar as it involves the search for authenticity on the part of the leader, limits the risk of hubris by exploring and connecting with the true self.

We are, however, aware that there remains a crucial problem with authentic leadership theory: although it is able to ground the CEO through the development of the true self and considering the needs of followers, and by this attenuate the risk of hubris, there is nothing to suggest that authentic leadership can, by the same token, reduce unethical use of power. If we adhere to the previous definition of authenticity developed by Harter (2002), it is obvious that an individual can be authentic and act immorally. Supporters of authentic leadership theory reject this idea, and assert that there is something inherently moral in the very fact of being one’s true self. To support this hypothesis, they cite an empirical study which demonstrates the relationship between authentic leadership and ethical behavior (Walumbwa et al. 2008). They also provide a more theoretical discussion of the moral component of ALT (Chan et al. 2005; Hannah et al. 2005). Chan et al. (2005) point out that one of the main arguments in favor of viewing authentic leadership as a form of moral leadership is that it implies a high level of moral development. Hannah et al. (2005) provide another argument based on two concepts: the self-concept (Kihlstrom et al. 2003; Lord and Brown 2004; Markus and Wurf 1987) and moral agency (Bandura 1991, 1997). The authors state that authentic leaders are those whose self-concept is not only highly developed but also has a moral dimension that is itself particularly advanced and complex: “This moral self-concept sets the conditions for leaders to make moral decisions through the activation of and concordance between their current selves (i.e. who they are), possible selves (i.e. who they want to be) and current goals (i.e. what they want to accomplish proximally)”. And from this point of view: “morality is in part a function of one’s memories as encoded and stored from one’s moral experiences and reflections” (Hannah et al. 2005, p. 46). However, the existence of a moral self is not sufficient to guarantee that an individual will indeed provide ethical leadership, i.e., will exercise effective and moral control over his or her behavior and environment. The authors explain that this link between authentic leadership and ethical behavior implies a return to the concept of moral agency developed by Bandura, and they define moral leadership agency as “the exercise of control over a leader’s moral environment through the employment of forethought, intentionality, self-reactiveness, and self-reflectiveness to achieve positive moral effects through the leadership influence process” (Hannah et al. 2005, p. 47). The work carried out by Hannah et al. (2005) provides a conceptual framework linking authentic leadership and morality through the concept of moral agency. It clarifies the specific nature of the (moral) self among authentic leaders, compounds our understanding of the effectiveness of moral behavior by returning to the notion of moral agency, and emphasizes the key role played by the environment and ethical experiences of a leader. But the fact remains: however thorough the theoretical analysis, if there is a link between ethical behavior and authentic leadership as described by Avolio and Gardner (2005), it is mainly because positive and moral values are core aspects of their definition and their definition goes beyond the original definitions of authenticity.

In view of the discussion surrounding the moral component of authentic leadership, our position is the following: authentic leadership is a model of leadership development which is relevant if its purpose is to limit the psychological risks of hubris, especially those linked to a disconnection from the self and the fabrication of a false self. On the other hand, if we aim to apprehend the purely moral dimension which is an aspect of hubris, then authentic leadership has its limitations. One of the specificities of hubris is to combine both pathological and immoral dimensions, which is not to imply that pathological is synonymous with immoral. As discussed above, it is theoretically possible to be both authentic (i.e., to have a healthy self) and to act immorally. In the same way, it might be possible to be psychologically sick (i.e., to fabricate a false self) and act in ways which are considered moral. We should therefore not expect authentic leadership to provide all the answers to hubris prevention. It does offer an initial interpretative lens through which to understand CEO hubris and how action might be taken against it on a psychological level. An additional interpretative lens is provided by philosophical ethics, which enables us to incorporate a moral aspect into our understanding of CEO hubris and the actions which might be taken to guard against it.

Cultivating the Virtue of Reverence

Reverence

“Leadership (as opposed to tyranny) happens only where there is virtue, and reverence is the virtue on which leadership most depends” (Woodruff 2001, p. 165). According to Woodruff, leaders are moral while tyrants are immoral, and reverence is one of the cardinal virtues of leaders, while hubris is the main vice of the tyrant.

A virtue may be defined as an acquired capacity to do good (Comte-Sponville 2001). Woodruff defines it as: “the capacity to have certain feelings and emotions when this capacity has been cultivated through training and experience in such a way that it inclines those who have it to do the right thing” (Woodruff 2001, p. 62). In the following section, we draw on the tradition of virtue ethics first developed by philosophers (Aristotle 2002; Epictetus 2003; Hume 1967; Anscombe 1958; MacIntyre 1985; Comte-Sponville 2001), then in the field of business ethics (Solomon 1992; Bertland 2009), and more recently in leadership studies (Flynn 2008).

As in the case of hubris, we introduce the concept of reverence with reference to mythology, which will enable us to better understand its nature. In Homer’s Odyssey (2003), the Greek hero Ulysses, following the advice of the magician Circe, daughter of the god Helios, decides to consult a famous soothsayer (Tiresias) from the kingdom of Hades. He asks him about his voyage and the precautions he should take in order to return safe and sound to his wife Penelope and son Telemachus in Ithaca. The soothsayer warns him that the gods will want to check his heart before allowing him return home. He warns him in particular about the island of Thrinacia, where herds of sacred cattle belonging to Helios (Apollo) graze: Ulysses and his companions must in no way undermine their integrity, regardless of how hungry they may be. By the time they arrive on the island, between Scylla and Charybdis, they have already lost men and are forced to remain there because of unfavorable winds. As provisions become scarce, Ulysses asks his men to swear they will never touch the sacred cattle. He then leaves to seek the opinion of the gods, leaving his men alone. While he is gone, on the initiative of Eurylochos, they discuss matters and having weighed up the chances of being punished by the gods they decide to eat the cattle. They consider that even if the gods do decide to punish them, they would prefer to die quickly under their wrath than experience a slow and agonizing death from hunger. They also reckon that the discord between the gods will work in their favor and allow them to escape punishment. When he returns, Ulysses finds the massacred herd. The vengeance of Helios is swift and Ulysses returns to Ithaca alone, while those who thought they could outwit the gods perish. This passage from the Odyssey highlights the heroic nature of Ulysses. While the heroism of Achilles was based on his courage, that of Ulysses stems from his intelligence, an intelligence that is not only crafty and rational like that of Eurylochos (Dobbs 1987), but which is matched by a sound heart and knows its limits. It is an intelligence that is aware of the need to show reverence to the powers that surpass it, i.e., in the case of Ulysses the gods and their goodwill.

In his book Reverence: a forgotten virtue, the philosopher Paul Woodruff (2001) explores the origins and nature of the virtue of reverence. Reverence is above all a virtue of limits (knowing how to set them) and an awareness of one’s own limits as a human being (in both action and reason, as made clear in the passage from the Odyssey). Woodruff explains that: “Reverence is the virtue that keeps human beings from trying to act like gods” (Woodruff 2001, p. 4) and is therefore the opposite of hubris. Reverence prevents us from feeling godlike or from allowing ourselves to be mistaken for gods. It is the virtue that stops us from thinking we can defy or seek to outwit the gods, like the misguided travelers in the Odyssey.

Another figure of reverence is the Greek goddess Aidos, daughter of Prometheus and close companion of Nemesis. She symbolizes honor, humility, and restrained pride: “Now Aidos (Reverence), daughter of Prometheus (Forethought), gives to men virtue and valour’s joy” (Pindar, Olympian Ode 7., 1972, 44 f). The goddess also symbolizes shame, modesty and by extension chastity. According to Cassin (1996), Aidos precedes Dike; she represents modesty in all its forms, a mixture of honor, fear and respect. We are reminded that “it is a feeling of shame that for long periods in human history has allowed us to avoid, via self-control, an excess of egotism or delinquency” (Scherer 2001). Aeschylus describes an individual who displays the characteristics of reverence: “He is fully noble and reveres the throne of Aiskhyne (aidôs) and detests proud speech. He is slow to act disgracefully, and he has no cowardly nature” (Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes, 1926, 409 ff).

Building on ancient philosophy, Woodruff provides a contemporary definition of reverence as “the capacity to feel respect in the right way toward the right people and to feel awe towards an object that transcends particular human interests” (Woodruff 2001, p. 175). From Woodruff’s perspective, reverence is a state of profound awareness of one’s humanity that is felt in two ways: first, awareness of and respect for that which surpasses us, and second a moral connection with the other members of the human community. Woodruff also contrasts reverence to other virtues, in particular humility and respect. Humility includes the same acute awareness of one’s value and one’s place but the shift towards others as well as the experience of belonging to the human community are not part of its definition (Tangney 2002). And as for respect Woodruff explains: “I need one word for an ideal, “reverence”, and other words for the feelings—respect, awe, and shame—that may or may not serve that ideal. You can never follow an ideal to closely, but you can have too much—or too little—of the feelings to which it gives rise” (Woodruff 2001, p. 9).

The examples from ancient Greece should not suggest that reverence is a uniquely Western virtue. It is also to be found in ancient China, in the writings of Mencius and especially Confucius. His interviews mention reverence: “The consummate person holds in awe three things: tianming (fate), people of important position, and the words of the sages. Petty people do not know fate, they are unduly presumptuous with people in important positions and they ridicule the words of the sages” (The analects, 2008, XVI.8). The term used for reverence is Wei, which has several translations (Ren 2010): the fear that suppresses arrogance (the ideograph is phonetically close to the word for tiger), the dread that leads to avoidance, and the reverence (or awe) that causes us to hold something or someone in high esteem. It is this final meaning that is clearly used by Confucius, for whom the value of each individual and ultimately the harmony of the social order depend on reverence for three things: fate, those in power (Emperor/King) and the sages. Of the three, it is the first that Confucius values most highly: each person’s awareness of his/her place and the contribution he/she makes to the order of things. “It is possible to say that Confucius’ account of awe (reverence) is related to the re-establishment of a productive social order or Dao. It is connected with an important sensibility, one that gives rise to the social order with structured human relationships (ren (benevolence)), the presence of justice (yi (justice)), the respect for regulation (li (propriety)), the capacity for good judgment (zhi (wisdom)) and mechanisms promoting mutual trust (xin (fidelity))”(Ren 2010, p. 114). Here we find the notion that reverence has an historic role in the production of social order. It contributes to the construction of a daily ethic, one that is external. Later, under the Ming and Song dynasties, Confucianism localized the virtue of reverence within each individual and associated it with the search for self-awareness and personal sincerity, thereby defining an entire system of ethics.

Confucius provides us with a useful reminder that reverence is nurtured outside the self and on a daily basis. Inspired by Confucius, Woodruff assumes that the easiest way to positively experience and nurture reverence is via rites and ceremonies. Like all virtues, according to Aristotle (2002), it is by practicing reverence that it exists.

The Reverent Leader

There are very few studies which provide a contemporary portrait of a reverent leader. In order to characterize such a leader, we will draw on Woodruff’s (2001) chapter entitled “The reverent leader”, as well as on a study into reverent leadership in the educational environment (Rud and Garrison 2010).

First, the reverent leader is considered as the opposite of the tyrant and in terms of his or her quest for high moral ideals: Woodruff’s portrait of the reverent leader therefore depends on a moral definition of leadership, one where leaders are “good” (Ciulla 1995, 2005). But, as Woodruff makes clear, good leadership implies a moral ideal towards which the leader tends (for no individual can claim moral perfection). It is often a thin line that separates leadership from tyranny, especially since they often rely on the same means: Woodruff puts forward the example of persuasion, which can serve both leaders and tyrants equally well. It is therefore not so much the use of one means or another that makes the difference, but the ethics that are applied to these means. For Plato, justice is what distinguishes a good from a bad leader, but for Woodruff justice is not enough as it does not become rooted in feelings as reverence does: “so the weak cannot rely upon justice to restrain their powerful overlords, because justice, unlike reverence, is not a motivational restraint” (Woodruff 2001, p. 174).

Second, reverent leaders are individuals of sound judgment because they know how to take decisions even when they are clearly aware of the limitations of their own knowledge and power: they know many things but are not omniscient; they are capable of action but are not omnipotent. They are able to carry through the required decisions and avoid falling into the trap of overconfidence. They avoid becoming isolated. Finally, according to Rud and Garrison (2010), reverent leaders are not only aware of the limits of their own knowledge, but also understand that the instruments and techniques of reason are as nothing without a capacity for empathy and compassion towards others and the human community as a whole.

Third, a reverent leader will unhesitatingly adopt “ceremonious” behavior as a concrete sign of his or her respect, for he or she is aware of the importance of ceremony in the daily practice of reverence. Greeting people is one way to cultivate reverence and sow the seed of respect. It is not just a matter of maintaining a good image or reputation, but rather of making the most of situations where it is possible to experience and share a feeling of mutual reliance based on shared human values.

Finally, the reverent leader experiences relationships with reverent followers: to illustrate this particular point Woodruff cites the example of a quartet of amateur musicians who, having exchanged a look and allowed the first violin to play the first note, take a moment of silence to experience together a feeling of “awe”: “their egos as musicians are out of the picture (…) each has for a time lost the sense of being an individual with goals and values that might be at variance with the those of others” (Woodruff 2001, p. 47). The reverent leader treats his or her followers with respect and receives their respect in return. Shared reverence leads to mutual respect. The respect that a leader receives from his or her followers is not just uncritical veneration. It should not trigger the development of an inflated ego, as reverence is first and foremost respect for a transcendent object. What the followers respect is not the person of the leader, but the fact that he or she embodies the respect, shared by everyone, for justice, the common good, God or nature.

How Reverence Prevents Hubris

Hubris is not only an ego-pathology affecting the self and relationships with others. It is also a vice which includes a set of immoral attitudes and behaviors which are particularly obvious in relationships with others and the world at large. What Woodruff shows is the link between the disappearance on the one hand, of the top executive’s awareness of a superior power (God, laws, ideals) and, on the other hand, the loss of his or her bond with the community of humans. The former leads to excess and the quest for absolute power; the latter engenders contempt for others and the loss of one’s humanity.

We feel this virtue ethics approach to hubris as the vice of the tyrant, which is opposed to the virtue of reverence, offers a second and complementary lens through which to view the possible avoidance of hubris. More precisely, it emphasizes how the cultivation of reverence in the relationship with the world as well as with others could limit the risk of developing hubristic tendencies.

The first way in which reverence develops is our relationship with the world and the universe. We become aware of our humanity by experiencing a transcendent order. This order may be God, nature, man, or the universe, but it may also be the common good or an ideal. Woodruff emphasizes many times that it is wrong to associate reverence exclusively with religion: “Reverence has more to do with politics than religion” (Woodruff 2001, p. 5). It can express itself just as easily in the context of politics, economics, military affairs, or education. It is therefore not synonymous with faith (which is not a virtue but a belief) or even respect: “reverence is the capacity for respect (among other things). Respect is something you feel, reverence is the capacity to have feelings. It is not simply a feeling itself” (Woodruff 2001, p. 67). Woodruff highlights a crucial point here: reverence is a virtue of both power and the leader who possesses it, without which the leader becomes a tyrant. If we compare the reverent leader to the hubris-infected top executive, it is obvious that they are complete opposites. The disregard for law and rules, including those of the market and of states, and the arrogance towards those who are responsible for enforcing them, are as much a sign of the existence of hubris as the absence of reverence. The hubris-infected CEO recognizes no higher authority.

The second way in which reverence develops and is experienced is our relationship with others—our participation in the human community, in the polis. This is the meaning of the story told to Socrates by Protagoras (Plato 2009): in the beginning, he says, the gods asked Epimetheus and Prometheus to provide all newly created creatures with the qualities necessary for their survival. Unfortunately, Epimetheus used these qualities for the animals, leaving nothing for humankind. He then looked to Prometheus, who saw the damage that had been done (naked humans left with nothing). Prometheus decided to reveal knowledge of the arts and of fire to Hephaestus and Athena so that humankind might develop the scientific knowledge necessary for its survival. Despite this, even though humans had gained the ability to build cities, they went on to kill one another and wage war in a further threat to their survival. Zeus then asked Hermes to provide humans with two virtues—justice (Dike) and reverence (Aidos)—through which to establish rules in the cities and unite mankind by the heart. He made it clear that all should have these qualities (not just a minority), for these were civic virtues. This story by the sophist Protagoras illustrates the establishment of reverence in the cities and in the human community. Without the combination of Aidos and Dike, the cities would have wallowed in anomie and chaos, and hubris would have become widespread, leaving social relations tainted by injustice, trickery, arbitrariness, and violence (Vernant 2006). Likewise, in firms managed by hubris-infected CEOs, chaos, unbridled competition resembling a free-for-all and generalized contempt are destined to reign. A community of humans cannot exist around a tyrant. Contempt for individuals, and a lack of respect for the principles on which the community of humans rests, cause the hubristic CEO to break up collective dynamic processes and establish, in their place, relationships based on fear and violence, in which individuals are spurred to follow the CEO’s example of contempt for the laws and others. In this case a real culture of hubris can prevail, which emanates from the CEO and pervades the whole organization, even leading in extreme instances to bankruptcy as in the cases of Enron and Bear Stearns.

Moving Forward

Contributions

This article makes four main contributions on a theoretical level. First, it provides the fields of management and finance with the first attempt to define CEO hubris through the development of a framework which is both sufficiently detailed to convey its complexity and yet practical enough to render the future development of a measure feasible. Second, despite some limitations, it brings to light the relevance of authentic leadership development in the specific context of strategic leadership, in which top executives are at risk of developing hubris. Previous literature on authentic leadership has discussed its relevance to managers within the organization, but not specifically to CEOs. We highlight the fact that authentic leadership, in as far as it builds on the true self and the development of authentic relationships, has the potential to limit the psycho-pathological dimensions of hubris. Third, it makes a contribution to the virtue ethics approach by emphasizing the relevance of one particular virtue to top executives. In so doing, we heed the statement that “managers need to add virtue ethics, or more precisely an attention to virtues and vices of human character, as a fully-equal complement to moral reasoning according to deontological or consequentialist teleological formulations” (Whetstone 2001, p. 102). The fourth contribution made by this paper results from its multidisciplinary nature. We first explore work from the fields of mythology, psychology, and ethics and we then apply the results of our analysis to the field of business ethics, and more specifically leadership ethics. We extend our ideas by applying our research to one particular figure, the CEO, and show how contributions based on positive psychology and virtue ethics can complement each other. Our framework depicting CEO hubris and our proposed solutions are multi-faceted, which would not be possible if we limited our analysis to one field. We are therefore able to provide a more holistic view, which is respectful of the complexity of CEO psychology.

Future Research

Our discussion of the nature of CEO hubris and the ways in which it might potentially be prevented or its effects attenuated leads us to identify three main areas which could be addressed in future research.

Strategic Leadership Ethics

To date, and as far as we are aware, the field of strategic leadership does not address the specific issue of top executive ethics. The authoritative work on strategic leadership (Finkelstein et al. 2009) emphasizes the role of top executive values but is still far from putting forward a general approach to top executive morality. Work on leader morality in business ethics (e.g., Ciulla et al. 2005; Price 2008; Palmer 2009) deals specifically with these issues from a more philosophical standpoint. We feel that a new approach, which we term strategic leadership ethics, is needed to bridge the gap between these two approaches. Strategic leadership examines topics which link the characteristics of executives to those of the firm, either by analyzing relationships (typically, linking performance or firm strategy to the CEO’s characteristics) or by looking at more specific subjects such as the interaction between top management and the board (for a review, see Finkelstein et al. 2009). In most work of this type, the moral dimension is conspicuous by its absence. As an example, we can refer the myriad papers in strategic management or in finance which deal with executive compensation. These are mostly based on an agency theory approach, in which compensation must be designed to align managers’ interests with those of shareholders. The moral aspect of executive compensation is reduced to this need for alignment, and does not consider wider ethical issues such as fairness or justice. Work in leadership ethics deals with the moral aspects of executive compensation (e.g., Conger 2005) from a more conceptual standpoint, but the two approaches rarely—if ever—meet. We conclude that approaches dealing with business realities and top management, such as those carried out in strategic leadership, could usefully include an ethical dimension which would widen the scope of what is currently a rather narrow debate.

Authentic Leadership and Hubris

We posit that investment in authentic leadership development by organizations or executives provides a potential means to prevent or limit the hubristic tendencies of business leaders. Future research needs to address the reality of the supposed negative relationship between authentic leadership and hubris. This would require the measurement of authentic leadership and hubris in a large sample of business leaders—a project which would present some special challenges. While there exists a validated questionnaire to capture authentic leadership (Walumbwa et al. 2008), to date there exist no validated measures of hubris which would be suitable for use in large samples. Related concepts such as narcissism and overconfidence have been used in strategic management (e.g., Chatterjee and Hambrick 2007) and finance (e.g., Malmendier and Tate 2005, 2008). However, as our framework describing executive hubris demonstrates, these concepts are not actually the same as hubris. Overconfidence and narcissism are not specific to a power context in the way that hubris is. In addition, they do not characterize the assimilation of the self with power as hubris does; nor do they describe the disregard for higher authority which is present in executive hubris. A first step towards testing the hypothesized negative relationship between executive hubris and authentic leadership would be to use the hubris framework as a starting point for the development and validation of a tool enabling the measurement of executive hubris. A further difficulty would be to obtain a sufficient response rate in surveys of the executive population. This is, however, probably not an insurmountable problem. For example, Cycyota and Harrison (2006) suggest a number of ways to access top executives in a meta-analysis of research into top executives which is reliant on a questionnaire-based approach.

Reverence and Hubris

In our paper, we put forward the idea of reverence as a way to cultivate a sense of proportion among CEOs which will prevent them from developing hubris, or will reduce existing hubristic tendencies. This opens up a number of possibilities for future research. As reverence is a forgotten virtue (Woodruff 2001), studies might consider the extent to which reverence-type characteristics exist among executives. This could be done using either a qualitative approach based on interviews with executives and their followers or through a quantitative study on a representative sample of executives, and would provide an indication of the state of the virtue of reverence in the current business environment. A second avenue to explore would be the expected negative relationship between reverence and hubris. Finally, it would be interesting to seek empirical confirmation of the theoretical positive link between authentic leadership and morality. Studies of reverence in large samples of executives would certainly run into the same problems of measurement and access to sufficient data mentioned above in the context of hubris and authentic leadership. We feel, however, that with careful research design these could be overcome. For example, Peterson and Seligman (2004) provide methods for measuring positive characteristics, including virtues.

Limits

The conceptual analysis presented in this paper suffers from a number of limits which mean that its implications should be considered with a degree of caution. First, our research is focused on the individual, as we feel that understanding the real nature of executive hubris is a necessary first step towards its prevention and/or attenuation. This is not to deny, however, the existence of hubris in a wider context. The relationship of a hubristic CEO to the rest of the top management team is likely an important aspect of CEO hubris: does its existence imply collective hubris in the top management team, or might other top management team members be able to rein in a hubristic CEO? The relation to the organization could also be a key to understanding the types of context in which CEO hubris develops. We might wonder which types of governance structures are better at encouraging practices which prevent hubris or, more generally, which types of organizations discourage hubris and foster more positive and virtuous qualities in the CEO. As in the definition developed by Luthans and Avolio (2003), authentic leadership in organizations is “a process that draws from both positive psychological capacities and a highly developed organizational context …” (p. 243).