Abstract

Non-adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET) for breast cancer (BC) is common. Our goal was to determine the associations between psychosocial factors and ET non-persistence. We recruited women with BC receiving care in an integrated healthcare system between 2006 and 2010. Using a subset of patients treated with ET, we investigated factors related to ET non-persistence (discontinuation) based on pharmacy records (≥90 days gap). Serial interviews were conducted at baseline and every 6 months. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT), Medical Outcomes Survey, Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (TSQM), Impact of Events Scale (IES), Interpersonal Processes of Care measure, and Decision-making beliefs and concerns were measured. Multivariate models assessed factors associated with non-persistence. Of the 523 women in our final cohort who initiated ET and had a subsequent evaluation, 94 (18 %) were non-persistent over a 2-year follow-up. The cohort was primarily white (74.4 %), stage 1 (60.6 %), and on an aromatase inhibitor (68.1 %). Women in the highest income category had a lower odds of being non-persistent (OR 0.43, 95 % CI 0.23–0.81). Quality of life and attitudes toward ET at baseline were associated with non-persistence. At follow-up, the FACT, TSQM, and IES were associated with non-persistence (p < 0.001). Most women continued ET. Women who reported a better attitude toward ET, better quality of life, and more treatment satisfaction, were less likely to be non-persistent and those who reported intrusive/avoidant thoughts were more likely to be non-persistent. Interventions to enhance the psychosocial well-being of patients should be evaluated to increase adherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET) is the standard of care for all women with hormone receptor positive breast cancer [1]. Endocrine therapy reduces the rates of mortality, local recurrence, and new primary breast cancers [2–8]. Studies suggest that patients may benefit from 10 years as opposed to 5 years of therapy [9, 10]. Despite these benefits, substantial variations occur in women’s use of these therapies [11–13]. Some patients fail to initiate recommended therapy [12], delay initiation [14], or discontinue therapy early [11, 15, 16]. Any deviation from recommended adjuvant therapy may reduce its survival benefit [17]. Understanding the factors associated with treatment, non-persistence and discontinuation may help us to develop interventions to improve adherence to endocrine therapy [18].

Our group and others have studied the demographic, clinical, and financial factors associated with discontinuation of ET [11, 16, 19, 20]. However, many of these studies relied on large administrative databases that are often required to measure adherence. In addition, most of the prior studies on this topic did not include patient-reported outcome measures, or information about psychosocial factors and patient preferences.

The Breast Cancer Quality of Care Study (BQUAL) is a prospective cohort study of factors associated with suboptimal use of adjuvant chemotherapy and ET in women with early-stage breast cancer. We have previously shown that the perception of poor physician–patient communication, negative beliefs regarding efficacy of the medication, and fear of toxicities are associated with failure to initiate hormone therapy [12]. We now present data on the associations of demographic and clinical factors, psychosocial factors, quality of life, and patient treatment satisfaction with the risk of ET non-persistence among women who had initiated it.

Methods

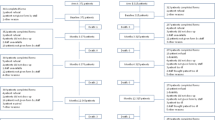

Details of the BQUAL study have been described elsewhere [21]. Briefly, between 2006 and 2010, women >20 years of age with newly diagnosed, histologically confirmed, primary breast cancer, stages I–III, were recruited from three sites [Columbia University Medical Center and Mount Sinai School of Medicine (CUMC/MSSM) in New York City, Kaiser-Permanente of Northern California (KPNC), and Henry Ford Health System (HFHS)]. Complete pharmacy records were only available from KPNC, and therefore the current study is limited to patients enrolled at that site. All interviews were conducted over the telephone. Women who were non-English speaking, had less than 100 days of follow-up, had a prior history of cancer, or had no access to a telephone were excluded.

All participants were enrolled within 12 weeks of diagnosis. Baseline interviews were completed at or shortly after diagnosis. For women on hormone therapy, follow-up interviews were conducted every 6 months for the first 2 years, and annually thereafter until conclusion of the study.

For this analysis, we included patients who were confirmed to have hormone receptor positive disease on pathology report, who had at least two prescriptions for ET in the electronic pharmacy database, and who completed a baseline interview (n = 605). We excluded women with Stage IV breast cancer (n = 2), women who recurred/disenrolled/died within 2 years (n = 23), those who took their first and last ET prior to the baseline interview (n = 23), and subjects who had no interview after initiation of ET (n = 18). To ensure uniformity with timing, the patient-reported measures were analyzed from the first questionnaire administered after ET initiation.

The primary outcome measure was ET non-persistence based on electronic pharmacy records obtained through the first 24 months after initiation. Non-persistence was defined as a ≥90-day gap following the date of anticipated completion of any ET prescription (date of prescription + days of pills prescribed + 90 days). We also evaluated the number of women who re-started hormonal therapy after a gap. Follow-up time was stopped at the time of recurrence, however only four patients recurred, and only one was classified as non-persistent prior to recurrence.

Experienced research assistants conducted the interviews. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each site and the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC) Office of Research Protections (ORP) and Human Research Protection Office (HRPO). Written informed consent and HIPAA authorization were obtained from patients prior to study initiation.

Study variables

Demographic, tumor, and treatment measures

From the baseline survey, self-reported information included sociodemographic characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, education, annual household income, employment, marital status). Tumor characteristics abstracted from the medical record included AJCC disease stage (I, II, III, or unknown), grade, nodal status, and tumor size. The Charlson Comorbidity Index [22] score was calculated from 12 months before to 3 months after diagnosis.

Quality of life was assessed at baseline and follow-up with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy: General (FACT-G), which is composed of subscales assessing Physical Well-Being, Social/Family Well-Being, Emotional Well-Being, and Functional Well-Being, along with the breast cancer subscale (FACT-B) [23]. The item response range is 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much).

Decision-making difficulty, preferences, and considerations were assessed at baseline. The perceived level of difficulty in making the treatment decision was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = extremely difficult to 5 = very easy. [24] A measure of patient–physician communication quality was composed of 5 items and evaluated the extent to which the participant agreed (1 = very strongly disagree through 6 = very strongly agree) with statements regarding the sufficiency of information provided by the physician upon which to base a treatment decision; whether the benefits and risks of HT were explained adequately; if the doctor solicited the patient’s opinion regarding treatment; and whether the physician believed the participant’s comorbidities precluded adjuvant therapy. Decision-making considerations included physical considerations, the negative decisional balance, positive decisional balance, and concrete considerations [25].

The Medical Outcomes Social Support Survey (MOS) [26] was assessed at baseline to evaluate various aspects of social support (emotional, tangible, affectionate, and positive social interactions). The item response range is 1–5 (from “none of the time” to “all of the time”).

Treatment satisfaction was measured with the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM) and assessed at follow-up [27]. The TSQM is a 14-item validated instrument (with items scored 0–100) to assess patients’ satisfaction with medication, providing scores for 4 scales (side effects, effectiveness, convenience, and global satisfaction).

Patient breast cancer-specific distress was measured using the 15-item version of the Impact of Events Scale (IES) and assessed at follow-up, which queries intrusive and avoidant thoughts about a distressing event (breast cancer) over the past 7 days. Each item has a scoring range of 0–5 [28, 29]. We also evaluated this outcome based on a total score of >24 or not based on prior studies evaluating post-traumatic stress disorder with this cut-off [30].

Patient’s preferred treatment decision-making roles were assessed at follow-up using a modified version of the Interpersonal Processes of Care measures (IPC) short form [31]. The survey assesses several subdomains of communication, patient-centered decision making, and interpersonal style. The item score range is 1–5.

Endocrine symptoms (hot flashes and vaginal itching, bleeding, dryness, and discharge) were assessed with a modified version of the Memorial symptoms questionnaire [32].

Data analysis

We compared the characteristics of patients who were non-persistence to ET with those who were not using Chi-square tests. We conducted multivariate logistic regression analyses of the relationships between demographic and clinical characteristics and ET non-persistence to determine covariates for the final model. Based on these results, we developed a series of multivariate logistic regression models of the associations between each of the psychosocial assessments and non-persistence, controlling for age and income. A stepwise logistic regression including all of the covariates was performed. An exploratory analysis looking at each question was performed to determine what factors were driving the observed associations. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

We identified 601 patients with HR-positive breast cancer who met our initial inclusion criteria. Of these, 523 initiated therapy and had a baseline and subsequent interview. The cohort was primarily white (74.4 %), stage 1 (60.6 %), and on an aromatase inhibitor (68.1 %) (Table 1). Of those patients, 94 (18 %) were non-persistent. If the 18 patients were included that discontinued prior to the first interview, the total non-persistence rate was 20.7 %. The median time from diagnosis to the first assessment was 204 days; this did not differ between the groups. The median follow-up time of the cohort following ET initiation was 730 days, with a mean of 658 days (range 60–730). Of the patients who were non-persistent, the median was 320 days with a mean of 329 days (range 60–638). If non-persistence was categorized as a 45-day gap, 169 (32.3 %) patients were non-persistent and 124 (73.4 %) re-started ET.

Of the 94 patients who were non-persistent with ET, 48 (41 %) re-started it at some point. The median time to re-starting ET was 152 days. Baseline characteristics were the same in those who re-started therapy compared to those who did not (data not shown). Compared to women in the lowest household income group (<$50,000), women who had a household income of >$90,000 were half as likely to interrupt their ET (OR 0.47, 95 % CI 0.26–0.85). No association with ET non-persistence was observed for other baseline characteristics, type of hormone therapy (aromatase inhibitor vs. tamoxifen), or receipt of chemotherapy. In a multivariate analysis of clinical and demographic factors, only household income remained associated with ET non-persistence (OR 0.43, 95 % CI 0.23–0.81) (Table 1). Covariates for the multivariate psychosocial variable models included age and variables that were significant at p < 0.05 in the univariate analysis. Of the 94 patients who were non-persistent, 38 (40 %) reported a reason, and of these, 33 % reported that the non-persistence was due to side effects. ET symptoms, were not associated with non-persistence (Table 2).

At baseline, low scores on global and the BC subscale of the FACT were associated with non-persistence. In a multivariate analysis controlling for income and age, non-persistence was associated with overall quality of life (OR 0.98, 95 % CI 0.89–0.98). In addition, patients with more positive attitudes about ET were less likely to be non-persistent (OR 0.51, 95 % CI 0.32–0.81). Physical and concrete decision-making concerns were associated with non-persistence, but decision-making preferences and decision-making difficulty were not. Social support total and subscale scores were not associated with subsequent ET non-persistence (Table 2; Fig. 1).

At follow-up (first assessment after ET initiation), in a multivariate analysis controlling for income and age, non-persistence was associated with overall quality of life (OR 0.97, 95 % CI 0.95–0.99), as well as with each of the general subscales (physical, social, emotional, and functional) and the breast cancer concerns subscale (Table 3; Fig. 2). In addition, lower scores on global treatment satisfaction were also associated with subsequent non-persistence (OR 0.99, 95 % CI 0.99–1.00). Interpersonal processes of care (i.e., patient–physician communication) were not associated with non-persistence.

Higher scores on the impact of events questionnaire were also associated with ET non-persistence (Table 3; Fig. 2). In the multivariate analysis, intrusive thoughts (OR 1.04, 95 % CI 1.01–1.07), avoidance (OR 1.03, 95 % CI 1.01–1.06), and the summary score (OR 1.02, 95 % CI 1.01–1.04) were each associated with ET non-persistence. We also found that patients with a score >24 had a higher odds of non-persistence (OR 1.92, 95 % CI 1.14–3.23) compared to those with scores ≤24.

In a stepwise multivariate analysis that included the global scores of each of the measures, income and age, only income and the Impact of Events Scale (OR 0.98, 95 % CI 0.97–0.99) remained statistically significantly associated with non-persistence.

Discussion

Despite the survival benefits of adjuvant hormonal therapy, we found that 18 % of breast cancer patients in our study who initiated adjuvant ET were non-persistent during the first 2 years of therapy. Women who reported better quality of life, a better attitude toward ET, and greater treatment satisfaction were less likely to interrupt their ET use. Women who reported increased distress, as measured by both increased intrusive and increased avoidant thoughts about breast cancer, were more likely to have non-persistence in ET. Global scores on social support measures, decision-making difficulty, and perceived quality of communication were not independently associated with risk of ET non-persistence.

We were not surprised to see the association between lower quality of life scores at baseline and follow-up and ET non-persistence. For women with breast cancer, quality of life is known to be associated with age, stage at diagnosis, and social support [33]. In a prior retrospective study, many women attributed their early discontinuation of ET to adverse effects and decreased quality of life [34]. We did not see an association between some common ET symptoms and non-persistence; however, the subset of patients who reported reasons for discontinuation commonly reported that it was due to side effects. Symptoms prior to initiation of therapy and during therapy may contribute to poor quality of life. An association between the number of symptoms experienced prior to, or after, treatment initiation and subsequent non-adherence has been previously reported [16, 35]. These results suggest that efforts to improve quality of life may be a productive avenue for improving adherence to hormone therapy.

In our study, high levels of breast cancer-specific emotional distress were associated with subsequent non-persistence in ET. We have previously shown that nearly 25 % of patients report levels of breast cancer-specific distress high enough to be consistent with PTSD shortly after diagnosis, and that the risk for PTSD symptoms was higher among black and Asian women than among white women [30]. In a retrospective analysis using electronic billing claims, non-adherence to hormone therapy was lower among patients with a history of claims for psychotherapy consultations or therapeutic support consultations than among women without such a history [36]. Although ET interruption was not associated with overall baseline social support, it was associated with specific questions on the scale dealing with understanding and sharing worries and problems. Early identification of emotional distress and therapeutic interventions to improve psychological well-being should be evaluated to improve the quality of breast cancer care.

Unlike prior studies that showed that improved patient–physician communication may enhance medication adherence [37, 38], our study did not find an association between ET non-persistence and any of the domains of interpersonal processes of care. A study by Liu et al. [39] reported that low-income breast cancer survivors with higher scores on “patient-centered” communication and greater self-efficacy scores on patient–physician communication at 18 months were more likely to continue to be on hormonal therapy at 36 months than patients with poorer scores.

Cancer treatment decisions confront both providers and patients with complex issues and challenges. These challenges are particularly pointed for women confronting the long-term adherence required for optimal curative treatment of breast cancer with ET. It has been suggested that patients mentally conduct a cost–benefit analysis; those who perceive a higher necessity for their medication have higher adherence, while those with more concerns are less adherent [40, 41]. Women in our study who had a positive attitude toward ET were significantly less likely to be non-persistent. Consistent with that view, adherence to ET has been reported to be associated with belief in the efficacy of the medication [42, 43] and with belief in the benefits of taking prescribed medications more generally [40, 44–46]. We found that higher satisfaction with treatment was associated with decreased risk of subsequent ET non-persistence. Specifically, we found that increased confidence about efficacy and belief that the good things outweighed the bad, were associated with decreased risk of non-persistence.

As we found in a prior analysis [19], women in the highest income bracket were significantly more likely to be adherent than women in the lowest income group. Low-income groups have traditionally been found to be vulnerable with regard to quality of health care, but we were surprised that income had such a strong association with non-persistence among patients who were part of an integrated healthcare system that minimized financial barriers to oral therapy. Income may be an inadequate proxy for overall financial resources, especially among the elderly, for whom net worth appears to be a more accurate predictor of the use of healthcare services [47]. In a previous study, we found that low net worth was associated with hormone therapy discontinuation, and partially explained the association between black race and non-compliance [20].

A study strength was that subjects were recruited prospectively at the time of breast cancer diagnosis or shortly thereafter; thus, the data were collected prior to the interruption of ET. In addition, our estimates of ET interruption were determined from electronic pharmacy records, which may have been more valid and less biased than self-report, which was utilized in most other studies. In the present study, we did not find associations between non-initiation of ET and several sociodemographic factors that previously were reported to influence compliance [15, 43, 48]. It is possible that there was insufficient statistical power due to modest sample sizes for some analyses. That concern notwithstanding, our study is one of the larger prospective studies to examine the association between patients’ perceptions and ET non-persistence.

This study had some important limitations. Because the patients were enrolled in an integrated healthcare plan, we could not explore issues related to access, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. We were also not able to assess the reasons for discontinuation among the 2 % of patients who discontinued prior to their first evaluation. It is possible that some patients may have filled their ET prescriptions outside of KPNC, but such behavior is known to be infrequent [48]. We only included patients who were English speaking and had access to a telephone and the majority of the patients were white, which may have implications for the generalizability of our results. Reassuringly, half of the patients who had ET non-persistence re-started treatment at some subsequent point during follow-up, however we do not know the reasons why they re-started. Finally, we performed multiple analyses; therefore, it is possible that some of the significant results, especially the exploratory analyses, were due to chance.

In conclusion, in this prospective cohort study of women with early-stage breast cancer, we found that the majority of women continued their hormone therapy, however patients under greater emotional duress, those who do not have positive attitudes about ET and those with lower quality of life appeared to be at the highest risk of discontinuing. A better understanding of modifiable psychological factors that can result in early discontinuation may inform targeted educational interventions to improve adherence.

References

Burstein HJ, Prestrud AA, Seidenfeld J, Anderson H, Buchholz TA, Davidson NE, Gelmon KE, Giordano SH, Hudis CA, Malin J, Mamounas EP, Rowden D, Solky AJ, Sowers MR, Stearns V, Winer EP, Somerfield MR, Griggs JJ (2010) American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline: update on adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 28(23):3784–3796. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3756

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) (2005) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 365(9472):1687–1717. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0

Baum M, Budzar AU, Cuzick J, Forbes J, Houghton JH, Klijn JG, Sahmoud T (2002) Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet 359(9324):2131–2139

Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, Paridaens R, Jassem J, Delozier T, Jones SE, Alvarez I, Bertelli G, Ortmann O, Coates AS, Bajetta E, Dodwell D, Coleman RE, Fallowfield LJ, Mickiewicz E, Andersen J, Lonning PE, Cocconi G, Stewart A, Stuart N, Snowdon CF, Carpentieri M, Massimini G, Bliss JM, van de Velde C (2004) A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med 350(11):1081–1092. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040331

Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, Robert NJ, Muss HB, Piccart MJ, Castiglione M, Tu D, Shepherd LE, Pritchard KI, Livingston RB, Davidson NE, Norton L, Perez EA, Abrams JS, Cameron DA, Palmer MJ, Pater JL (2005) Randomized trial of letrozole following tamoxifen as extended adjuvant therapy in receptor-positive breast cancer: updated findings from NCIC CTG MA.17. J Natl Cancer Inst 97(17):1262–1271. doi:10.1093/jnci/dji250

Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, Robert NJ, Muss HB, Piccart MJ, Castiglione M, Tu D, Shepherd LE, Pritchard KI, Livingston RB, Davidson NE, Norton L, Perez EA, Abrams JS, Therasse P, Palmer MJ, Pater JL (2003) A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med 349(19):1793–1802

Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, Buzdar A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF, Hoctin-Boes G, Houghton J, Locker GY, Tobias JS (2005) Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years’ adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet 365(9453):60–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17666-6

Thurlimann B, Keshaviah A, Coates AS, Mouridsen H, Mauriac L, Forbes JF, Paridaens R, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Gelber RD, Rabaglio M, Smith I, Wardley A, Price KN, Goldhirsch A (2005) A comparison of letrozole and tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 353(26):2747–2757. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052258

Davies C, Pan H, Godwin J, Gray R, Arriagada R, Raina V, Abraham M, Medeiros Alencar VH, Badran A, Bonfill X, Bradbury J, Clarke M, Collins R, Davis SR, Delmestri A, Forbes JF, Haddad P, Hou MF, Inbar M, Khaled H, Kielanowska J, Kwan WH, Mathew BS, Mittra I, Muller B, Nicolucci A, Peralta O, Pernas F, Petruzelka L, Pienkowski T, Radhika R, Rajan B, Rubach MT, Tort S, Urrutia G, Valentini M, Wang Y, Peto R (2013) Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: ATLAS, a randomised trial. Lancet 381(9869):805–816. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61963-1

Burstein HJ, Temin S, Anderson H, Buchholz TA, Davidson NE, Gelmon KE, Giordano SH, Hudis CA, Rowden D, Solky AJ, Stearns V, Winer EP, Griggs JJ (2014) Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol 32(21):2255–2269. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.54.2258

Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, Buono D, Kershenbaum A, Tsai WY, Fehrenbacher L, Lin Gomez S, Miles S, Neugut AI (2010) Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 28(27):4120–4128. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655

Neugut AI, Hillyer GC, Kushi LH, Lamerato L, Leoce N, Nathanson SD, Ambrosone CB, Bovbjerg DH, Mandelblatt JS, Magai C, Tsai WY, Jacobson JS, Hershman DL (2012) Non-initiation of adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: the Breast Cancer Quality of Care Study (BQUAL). Breast Cancer Res Treat 134(1):419–428. doi:10.1007/s10549-012-2066-9

Partridge AH, LaFountain A, Mayer E, Taylor BS, Winer E, Asnis-Alibozek A (2008) Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 26(4):556–562

Bickell NA, LePar F, Wang JJ, Leventhal H (2007) Lost opportunities: physicians’ reasons and disparities in breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol 25(18):2516–2521

Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J (2003) Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 21(4):602–606

Henry NL, Azzouz F, Desta Z, Li L, Nguyen AT, Lemler S, Hayden J, Tarpinian K, Yakim E, Flockhart DA, Stearns V, Hayes DF, Storniolo AM (2012) Predictors of aromatase inhibitor discontinuation as a result of treatment-emergent symptoms in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 30(9):936–942. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0261

Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, Buono D, Tsai WY, Fehrenbacher L, Kwan M, Gomez SL, Neugut AI (2011) Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 126(2):529–537. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-1132-4

Gould E, Mitty E (2010) Medication adherence is a partnership, medication compliance is not. Geriatr Nurs 31(4):290–298. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.05.004

Hershman DL, Tsui J, Meyer J, Glied S, Hillyer GC, Wright JD, Neugut AI (2014) The change from brand-name to generic aromatase inhibitors and hormone therapy adherence for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. doi:10.1093/jnci/dju319

Hershman DL, Tsui J, Wright JD, Coromilas EJ, Tsai WY, Neugut AI (2015) Household net worth, racial disparities, and hormonal therapy adherence among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 33(9):1053–1059. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3062

Neugut AI, Hillyer GC, Kushi LH, Lamerato L, Nathanson SD, Ambrosone CB, Bovbjerg DH, Mandelblatt JS, Magai C, Tsai WY, Jacobson JS, Hershman DL (2012) The Breast Cancer Quality of Care Study (BQUAL): a multi-center study to determine causes for noncompliance with breast cancer adjuvant therapy. Breast J 18(3):203–213. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4741.2012.01240.x

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J et al (1993) The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11(3):570–579

Llewellyn-Thomas HA, McGreal MJ, Thiel EC, Fine S, Erlichman C (1991) Patients’ willingness to enter clinical trials: measuring the association with perceived benefit and preference for decision participation. Soc Sci Med 32(1):35–42

Mandelblatt JS, Sheppard VB, Hurria A, Kimmick G, Isaacs C, Taylor KL, Kornblith AB, Noone AM, Luta G, Tallarico M, Barry WT, Hunegs L, Zon R, Naughton M, Winer E, Hudis C, Edge SB, Cohen HJ, Muss H (2010) Breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy decisions in older women: the role of patient preference and interactions with physicians. J Clin Oncol 28(19):3146–3153. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.24.3295

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL (1991) The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 32(6):705–714

Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, Colman SS, Kumar RN, Brod M, Rowland CR (2004) Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2(12):26

Weiss DS, Marmar CR (1997) The Impact of Event Scale—revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM (eds) Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. Guilford Press, New York, pp 399–411

Baider L, Andritsch E, Uziely B, Goldzweig G, Ever-Hadani P, Hofman G, Krenn G, Samonigg H (2003) Effects of age on coping and psychological distress in women diagnosed with breast cancer: review of literature and analysis of two different geographical settings. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 46(1):5–16

Vin-Raviv N, Hillyer GC, Hershman DL, Galea S, Leoce N, Bovbjerg DH, Kushi LH, Kroenke C, Lamerato L, Ambrosone CB, Valdimorsdottir H, Jandorf L, Mandelblatt JS, Tsai WY, Neugut AI (2013) Racial disparities in posttraumatic stress after diagnosis of localized breast cancer: the BQUAL study. J Natl Cancer Inst 105(8):563–572. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt024

Stewart AL, Napoles-Springer AM, Gregorich SE, Santoyo-Olsson J (2007) Interpersonal processes of care survey: patient-reported measures for diverse groups. Health Serv Res 42(3 Pt 1):1235–1256. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00637.x

Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M, Kasimis BS, Thaler HT (2000) The memorial symptom assessment scale short form (MSAS-SF). Cancer 89(5):1162–1171

Kwan ML, Ergas IJ, Somkin CP, Quesenberry CP Jr, Neugut AI, Hershman DL, Mandelblatt J, Pelayo MP, Timperi AW, Miles SQ, Kushi LH (2010) Quality of life among women recently diagnosed with invasive breast cancer: the pathways study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 123(2):507–524. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-0764-8

Bowles EJA, Boudreau DM, Chubak J, Yu O, Fujii M, Chestnut J, Buist DS (2012) Patient-reported discontinuation of endocrine therapy and related adverse effects among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Oncol Pract 8(6):e149–e157. doi:10.1200/JOP.2012.000543

Kidwell KM, Harte SE, Hayes DF, Storniolo AM, Carpenter J, Flockhart DA, Stearns V, Clauw DJ, Williams DA, Henry NL (2014) Patient-reported symptoms and discontinuation of adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy. Cancer 120(16):2403–2411. doi:10.1002/cncr.28756

Brito C, Portela MC, de Vasconcellos MT (2014) Adherence to hormone therapy among women with breast cancer. BMC Cancer 14:397. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-14-397

Piette JD, Heisler M, Krein S, Kerr EA (2005) The role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressures. Arch Intern Med 165(15):1749–1755. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.15.1749

Pellegrini I, Sarradon-Eck A, Soussan PB, Lacour AC, Largillier R, Tallet A, Tarpin C, Julian-Reynier C (2010) Women’s perceptions and experience of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy account for their adherence: breast cancer patients’ point of view. Psychooncology 19(5):472–479. doi:10.1002/pon.1593

Liu Y, Malin JL, Diamant AL, Thind A, Maly RC (2013) Adherence to adjuvant hormone therapy in low-income women with breast cancer: the role of provider-patient communication. Breast Cancer Res Treat 137(3):829–836. doi:10.1007/s10549-012-2387-8

Horne R, Weinman J (1999) Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res 47(6):555–567

Van Liew JR, Christensen AJ, de Moor JS (2014) Psychosocial factors in adjuvant hormone therapy for breast cancer: an emerging context for adherence research. J Cancer Surviv Res Pract 8(3):521–531. doi:10.1007/s11764-014-0374-2

Fink AK, Gurwitz J, Rakowski W, Guadagnoli E, Silliman RA (2004) Patient beliefs and tamoxifen discontinuance in older women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 22(16):3309–3315. doi:10.1200/jco.2004.11.064

Kimmick G, Anderson R, Camacho F, Bhosle M, Hwang W, Balkrishnan R (2009) Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 27(21):3445–3451

Iihara N, Tsukamoto T, Morita S, Miyoshi C, Takabatake K, Kurosaki Y (2004) Beliefs of chronically ill Japanese patients that lead to intentional non-adherence to medication. J Clin Pharm Ther 29(5):417–424. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2004.00580.x

Heisey R, Pimlott N, Clemons M, Cummings S, Drummond N (2006) Women’s views on chemoprevention of breast cancer: qualitative study. Can Fam Phys 52:624–625

Bickell NA, Weidmann J, Fei K, Lin JJ, Leventhal H (2009) Underuse of breast cancer adjuvant treatment: patient knowledge, beliefs, and medical mistrust. J Clin Oncol 27(31):5160–5167. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9773

Allin S, Masseria C, Mossialos E (2009) Measuring socioeconomic differences in use of health care services by wealth versus by income. Am J Public Health 99(10):1849–1855. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.141499

Livaudais JC, Hershman DL, Habel L, Kushi L, Gomez SL, Li CI, Neugut AI, Fehrenbacher L, Thompson B, Coronado GD (2012) Racial/ethnic differences in initiation of adjuvant hormonal therapy among women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 131(2):607–617. doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1762-1

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Center of Excellence Award (BC043120) to Drs. Neugut/Hershman; the NCI R01 (CA105274) to Dr. Kushi; the Department of Defense (DAMD-17-01-1-0334) to Dr. Bovbjerg; and the NCI R01 (CA124924 and 127617) and U10 (CA 84131) to Dr. Mandelblatt. Drs. Hershman is the recipient of funding from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest. All of the authors are responsible for the data analysis and interpretation. No additional individuals were involved in the analysis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hershman, D.L., Kushi, L.H., Hillyer, G.C. et al. Psychosocial factors related to non-persistence with adjuvant endocrine therapy among women with breast cancer: the Breast Cancer Quality of Care Study (BQUAL). Breast Cancer Res Treat 157, 133–143 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3788-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3788-x