Abstract

Breast cancer is a global health concern. In fact, breast cancer is the primary cause of death among women worldwide and constitutes the most expensive malignancy to treat. As health care resources are finite, decisions regarding the adoption and coverage of breast cancer treatments are increasingly being based on “value for money,” i.e., cost-effectiveness. As the evidence about the cost-effectiveness of breast cancer treatments is abundant, therefore difficult to navigate, systematic reviews of published systematic reviews offer the advantage of bringing together the results of separate systematic reviews in a single report. As a consequence, this paper presents an overview of systematic reviews of the cost-effectiveness of hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy for breast cancer to inform policy and reimbursement decision-making. A systematic review was conducted of published systematic reviews documenting cost-effectiveness analyses of breast cancer treatments from 2000 to 2014. Systematic reviews identified through a literature search of health and economic databases were independently assessed against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Systematic reviews of original evaluations were included only if they targeted breast cancer patients and specific breast cancer treatments (hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy only), documented incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, and were reported in the English language. The search strategy used a combination of these key words: “breast cancer,” “systematic review/meta-analysis,” and “cost-effectiveness/economics.” Data were extracted using predefined extraction forms and qualitatively appraised using the assessment of multiple systematic reviews (AMSTAR) tool. The literature search resulted in 511 bibliographic records, of which ten met our inclusion criteria. Five reviews were conducted in the early-stage breast cancer setting and five reviews in the metastatic setting. In early-stage breast cancer, evidence about trastuzumab value differed by age. Trastuzumab was cost-effective only in women with HER2-positive breast cancer younger than 65 years and over a life-time horizon. The cost-effectiveness of trastuzumab in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer yielded conflicting results. The same conclusions were reached in comparisons between vinorelbine and taxanes. In both early stage and advanced/metastatic breast cancer, newer aromatase inhibitors (AIs) have proved cost-effective compared to older treatments. This overview of systematic reviews shows that there is heterogeneity in the evidence concerning the cost-effectiveness of hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy for breast cancer. The cost-effectiveness of these treatments depends not only on the comparators but the context, i.e., adjuvant or metastatic setting, subtype of patient population, and perspective adopted. Decisions involving the cost-effectiveness of breast cancer treatments could be made easier and more transparent by better harmonizing the reporting of economic evaluations assessing the value of these treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Breast cancer, a type of cancer that develops from breast tissue, [1] is a global health concern. In fact, breast cancer is the primary cause of death among women worldwide [2] and constitutes one of the most expensive malignancies to treat. [3] As such, breast cancer puts a heavy burden on patients and their families, as well as healthcare systems across the world. [4].

Strategies to combat the breast cancer pandemic are geared toward prevention, early detection, and treatment. [5] Over the past decades, medical breakthroughs have shown that breast cancer is a multifaceted disease with different subtypes and stages. This medical progress has shaped the development of strategies to treat breast cancer more efficiently.

Since health care systems worldwide have finite resources, the adoption (clinical decision) and coverage of new breast cancer treatments are increasingly being made based on the concept of “value for money” (cost-effectiveness), which takes into consideration the costs associated with the selection of a particular treatment over its comparators. [6–8].

There is a plethora of published studies (individual studies and systematic reviews) of the cost-effectiveness of breast cancer treatments that decision-makers can access. However, for most decision-makers, it is difficult to navigate through and utilize this large body of evidence when making decisions routinely. Systematic reviews of published systematic reviews are designed to help solve this issue by bringing together the results of separate systematic reviews in a single report. Systematic reviews themselves vary in terms of quality and scope and may duplicate studies. [9, 10] Using evidence from reviews of systematic reviews allows quick and easy comparison of existing findings of a large volume of studies, and identification of the direction (unidirectional or conflicting evidence) and magnitude of the evidence.

The objective of this study was to systematically identify and review published systematic reviews on the cost-effectiveness of hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy for breast cancer, building on the methods proposed by Smith et al. [10] Based on the findings of the review, the authors make recommendations for future research aimed at documenting the cost-effectiveness of breast cancer treatments in order to enlighten policy and reimbursement decision-making.

Methods

Sources and search strategy

A systematic review was conducted of published systematic reviews documenting the cost-effectiveness of breast cancer treatments. As such, the unit of analysis in the current study is a systematic review of studies of the topic under evaluation, unlike traditional systematic reviews. The systematic reviews were identified through a literature search of the following databases for the period January 1, 2000–December 31, 2014: Ovid Medline and Embase, the US National Library of Medicine’s PubMed, and ISI’s Web of Knowledge, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Center for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) database (including the National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, and Health Technology Assessments), and Econlit. Keywords used to develop the search strategy comprised “breast cancer” terms coupled with “systematic review/meta-analysis” and “cost-effectiveness/economics” terms using Boolean operators as well as truncation and wildcard operators (see Appendix). In addition, a manual search of the reference lists of previously captured articles was carried out to increase the likelihood of locating relevant systematic reviews. The grey literature was also searched using “Grey Matters,” [11] a tool developed by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) to help find evidence that is not commercially published. Finally, one expert AJM in the field of breast cancer provided the authors with feedback on potential sources of evidence on the topic.

Review selection process

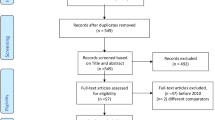

The records obtained from the literature search, containing titles and abstracts of the reviews, were exported into Refworks. Figure 1 depicts the selection process of articles included in our systematic review. First, duplicates were identified and removed from the pool of bibliographic records. Then, three independent reviewers (VD, RT, and VS) screened the abstracts of the unique records, and those considered out of scope [no systematic review conducted, review targeting interventions other than treatments and a different disease than breast cancer] were discarded. Afterward, available full-text copies of the remaining papers were retrieved, perused, and assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by VD, RT, and VS. Disagreements were resolved by consulting with two additional reviewers (HX and AJM). Systematic reviews were included only if they targeted breast cancer patients, specific breast cancer treatments (hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy), documented incremental cost-effectiveness ratios and were reported in English language. The review was not restricted to a specific subtype or stage of breast cancer. However, articles were excluded if they presented costs or benefits information only, described a methodological approach only, or were non-journal papers except reports.

Study characteristics, findings, and quality assessment of reviews

Data from the included papers were extracted and synthesized (numerically) using predefined extraction forms documenting the characteristics of the systematic reviews (Tables 1, 2). The characteristics of the studies included in the assessed systematic reviews (Tables 3, 4, 5) were interventions, objectives, main conclusions, (Table 6) and the quality assessment of systematic reviews (Table 7). As suggested by Smith et al. [10] the quality and strength of evidence of each systematic review were assessed against a validated tool named assessment of multiple systematic reviews (AMSTAR). [12] The tool covers 11 domains from the establishment of the research question to the assessment of publication bias. AMSTAR is purported to be an enhanced and refined version of previous tools. [12] Since the tool does not allow for quantifying the performance of the systematic reviews against its domain, we developed a scoring scale matching the fourth-point response choices of the AMSTAR, based on previously published approaches. [5, 13] The four-point response choices, Yes, No, Can’t answer, assign the scores 1, 0, 0. For dimensions that were not applicable, the maximum score was reduced by 1 for comparability purposes across studies. The new scoring scale was used to adapt the existing AMSTAR tool to fit our needs (Table 1). The scores were expressed in percentages to facilitate the comparison of the performances of the systematic review with regard to quality.

Results

Literature search

The literature search yielded 511 bibliographic records (including records obtained from manual and grey literature searches) (Fig. 1). From this initial pool of records, 56 duplicates were identified and excluded. Following the titles and abstracts review, 455 (including one reference retrieved by hand search) studies were rejected for being out of scope. Of the remaining records subject to the full-text review, seven were removed using the exclusion criteria. The final set of bibliographic records reviewed was composed of ten systematic reviews.

Characteristics of the reviews and their included studies

Ten systematic reviews that both assessed studies on the cost-effectiveness of breast cancer treatment strategies and met our inclusion criteria were published between 2001 and 2014. The reviews were similar in regard to their purpose, but different in the stated objectives and interventions compared. Table 2 highlights the main characteristics of each systematic review. Regarding the time horizon covered for review searches, only one study was from inception of the database to 2011. [14] For the remainder, three review searches covered 15 years of publications, [15–17] two review searches were conducted over a 10-year period, [18, 19] two review studies had a time horizon of 6 years, [20, 21] and the last two review searches covered, respectively, 9 [22] and 3 years. [23] The sample sizes of the systematic reviews ranged between four [16, 23] and 23. [20] Tables 3, 4, 5 highlight the main characteristics of studies that were included in each of the systematic reviews. All of the reviews covered a wide spectrum of geographical areas [Euro zone; North America; Asia Latin America; and Australasian eco zone (Table 3)] in which the individual economic evaluations were conducted. In terms of breast cancer stage, 54 % of economic evaluations assessed treatment strategies for advanced stage cancer, while 45 % of them evaluated treatment options for early stage. 59 % of these economic evaluations were cost-effectiveness analyses, while 41 % were cost-utility analyses. The majority (76 %) of these evaluations were model-based and the remaining evaluations were trial-based. With regard to the temporal framework of the economic evaluations included in the reviews, 18 and 82 % of these studies were conducted over a short-term (between 0 and 5 years) and long-term (beyond 5 years) periods, respectively. The most commonly adopted perspective in reviewed economic evaluations was the payer perspective (71 %). The societal perspective was adopted in 10 % of the cases, while other perspectives (different than payer or societal—e.g., US hospital) represented 19 % of the cases. Data sources were relatively well-documented in the majority of individual studies. These studies generally applied discounting, conducted sensitivity analyses, and presented incremental analyses.

Study findings and quality assessment of the reviews

The study findings can be categorized into two groups, results for early breast cancer and advanced/metastatic breast cancer. These results are summarized in Table 6.

Early breast cancer

Five reviews examined the cost-effectiveness of treatments for early breast cancer.

John-Baptiste et al. [17] reviewed economic evaluations that compared AIs (anastrozole and letrozole) versus tamoxifen. Studies included in this review suggest that choosing AIs for first-line therapy for early breast cancer represents good value for money compared to tamoxifen. However, John-Baptiste et al. [17] recommended that caution be used when drawing conclusions about the value of AIs versus tamoxifen, as these studies tend to overestimate the cost-effectiveness of AIs. Their results may, therefore, be suboptimal to inform policy decisions. This review was of relative good scientific quality (score = 70 %) as per the standards of the modified AMSTAR tool.

In the same vein, Frederix et al. [19] appraised economic evaluations comparing AIs (anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane, combinations) versus tamoxifen. Unfortunately, the included studies did not come to a consensus as to whether AIs represent better value for money compared to tamoxifen. In fact, some economic evaluations presented a very low incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) while others presented very high ICER, although they used very similar data sources. The review by Frederix et al. was judged of relatively good scientific quality (score = 70 %), according to the modified AMSTAR tool standards.

Ferrusi et al. [14] reviewed economic evaluations of adjuvant trastuzumab targeted therapy to assess the extent to which decision support recommendations were adopted by economic evaluations producers. The adjuvant use of trastuzumab was the base-case scenario in these economic evaluations, while the long-term use of trastuzumab in MBC was considered in sensitivity analyses. Trastuzumab appeared to be generally cost-effective when its use was limited to a year. The short-term use (base-case scenario) of trastuzumab was more cost-effective than longer term use (sensitivity analysis) from a health economic point of view. The cost-effectiveness of trastuzumab was heavily influenced by the choice of testing strategy (details not reported). The scientific quality of this review was judged fair (score = 60 %), according to the modified AMSTAR standards.

Chan et al. [18] assessed economic evaluations comparing trastuzumab versus standard treatment/chemotherapy without trastuzumab. The authors stated that the ICERs reported in their systematic review supported the conclusion that trastuzumab was cost-effective as adjuvant therapy in women with HER2-positive breast cancer younger than 65 years, over a life-time horizon. However, adjuvant trastuzumab was not found to be cost-effective when used in HER2-positive breast cancer patients older than 75 years, or with a time horizon of less than 10 years. Using the modified AMSTAR tool, this review was judged fair (score = 60 %) in terms of its scientific quality.

Norum 2006 [23] assessed the cost-effectiveness of adjuvant trastuzumab in early breast cancer and made recommendations for future economic evaluations. Even though the number of individual studies (4) included in the review was limited, the adjuvant trastuzumab in early breast cancer was found cost-effective, except for subgroups of stage III breast cancer and seniors (65 years and beyond). The scientific quality of this review was deemed relatively good (score = 70 %), based on the modified AMSTAR tool.

Advanced/metastatic breast cancer

In the metastatic setting, five reviews examined the cost-effectiveness of treatments for breast cancer.

Benedict et al. [21] evaluated the cost-effectiveness of aromatase inhibitors (AIs)—letrozole, exemestane, anastrozole, and fulvestrant in metastatic hormone receptor-positive breast cancer relative to either tamoxifen or megestrol as first- and second-line therapy, respectively. These analyses suggested, that AIs were highly cost-effective in the metastatic setting irrespective of country and the line of therapy. This review was judged of relative good scientific quality as suggested by the score (70 %) obtained using the modified AMSTAR tool.

Foster et al. [20] assessed the economic impact of various metastatic breast cancer (MBC) treatments including hormonal and targeted therapies. The results of the economic evaluations included in the review suggest that endocrine therapies were very cost-effective. Specifically, newer AIs (anastrozole and letrozole) were found to be cost-effective in the first-line therapy when compared to tamoxifen, in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. In addition, various studies included in the systematic review by Foster al. [20] looked at the cost-effectiveness of fulvestrant (second or third line option) in hormone receptor-positive postmenopausal women with MBC. The cost-effectiveness of adding fulvestrant to existing treatment sequences, including adding fulvestrant to a chemotherapy sequence, was either cost-saving or highly cost-effective compared to a non-fulvestrant sequence. In regard to the cost-effectiveness of targeted therapies, the ICERs were influenced by the chemotherapy that these targeted therapies were paired with. Trastuzumab was found cost-effective when administered alone as first-line therapy in HER2-positive breast cancer patients compared to standard chemotherapy. The same conclusion was reached when trastuzumab was combined with paclitaxel compared with chemotherapy alone or when trastuzumab was compared to Vinorelbine. However, the combination of trastuzumab plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone was not found cost-effective. Other targeted therapies were also assessed as part of the systematic review by Foster et al. [20]. The combination of lapatinib and capecitabine, for the treatment of HER2-positive advanced and MBC patients (not naïve to trastuzumab), was cost-saving compared with trastuzumab-containing regimens. The combination was not cost-effective compared to capecitabine alone or vinorelbine alone. The same conclusion was reached when bevacizumab was combined with chemotherapy regimens in the treatment of HER2-positive MBC patients. Using the modified AMSTAR tool, this review was judged fair (score = 60 %) in terms of its scientific quality.

Blank et al. [22] reviewed the data on the cost-effectiveness of cytotoxic chemotherapy and targeted therapy (trastuzumab and bevacizumab) for MBC. The pharmacoeconomic studies included in this review yielded varying conclusions. Evaluations on cytotoxic agents showed mainly favorable ICERs, while those on targeted therapies indicated both favorable and non-favorable ratios. Indeed, Bevacizumab used in combination with paclitaxel as first-line option was not cost-effective compared with paclitaxel alone. As for trastuzumab, its cost-effectiveness differed according to the perspective of the studies (payer, hospital, societal) and the regimen it was part of. The scientific quality of this review was considered relatively good (modified AMSTAR score = 70 %).

Parkinson et al. [15] appraised the quality of economic evaluations of trastuzumab in the metastatic setting, and identified potential determinants of conflicting results. Trastuzumab was paired with a taxane (docetaxel or paclitaxel), an AI (anastrozole), or a cytotoxic agent (capecitabine). The assessed economic evaluations were not in agreement regarding the cost-effectiveness of trastuzumab in the treatment of HER2-positive MBC. The authors suggested potential explanations for these results. The differences may be attributed to the judgments made by the authors selecting the comparators, extrapolating randomized controlled trial data, and making assumptions in modeling costs and outcomes. In terms of scientific quality, the review was judged fair with a modified AMSTAR score of 60 %.

Lewis et al. [16] aimed at evaluating the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of vinorelbine compared to taxane therapy (docetaxel or paclitaxel, both administered every 3 weeks) in the metastatic setting. The review yielded conflicting results. In fact, one economic evaluation reported that vinorelbine was a preferred strategy over taxane therapy, while another concluded that vinorelbine was less effective and less expensive than taxane therapy, and a third evaluation found vinorelbine to be inferior to taxanes. The authors concluded that additional studies were needed to shed light on the true cost-effectiveness of vinorelbine in treating metastatic breast cancer. This review had the highest score in terms of scientific quality (modified AMSTAR score = 100 %) among the systematic reviews.

Discussion

This review has focused on published systematic reviews of the cost-effectiveness of hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy for breast cancer, conducted from 2000 to 2014. A total of 511 bibliographic records were found, with 10 included and fully reviewed. The time horizon for literature review searches ranged from three [23] to 15 years [15–17]. In addition, the sample size of the systematic reviews varied between four [16, 23] and 23 studies [20]. Most economic evaluations covered a long-term temporal framework while adopting a model-based cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) design, and a payer perspective. The studies included in the review included patients from most of the world except for Africa. The study findings can be summarized as follows. First, in early stage postmenopausal hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, there was heterogeneity in the evidence regarding the cost-effectiveness of AIs versus tamoxifen, i.e., studies investigating these treatments both low and high ICERs. As such, additional studies are needed to shed light on the cost-effectiveness of AIs versus tamoxifen at this stage. [17, 19] That being said, we can reasonably anticipate that future economic studies will likely find AIs highly cost-effective compared to tamoxifen because of longer follow-up in adjuvant AI studies and lower cost of AIs since they have become all generic. In the advanced/metastatic breast cancer setting, newer AIs have proved cost-effective compared to older treatments. [20, 21] Second, the cost-effectiveness of trastuzumab was influenced by age and time horizon. Trastuzumab was cost-effective as adjuvant therapy in women with HER2 + breast cancer younger than 65 years and over a life-time horizon. However, trastuzumab was not found to be cost-effective as adjuvant therapy in HER2 + breast cancer patients older than 75 years or with a time horizon of less than 10 years. [18] The cost-effectiveness of trastuzumab was also evaluated in the metastatic setting. The systematic reviews appraising the cost-effectiveness of trastuzumab for metastatic breast cancer were inconclusive, meaning that individual evaluations yielded conflicting results. [15, 20] Similarly, Lewis et al. [16] assessed the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of vinorelbine compared to taxane therapy in the management of MBC. The review also yielded conflicting results. We did not find a connection between the discrepancies in cost-effectiveness results of studies and their geographical area of origin, although most studies were carried out in middle- to high-income countries. All the reviews were assessed for scientific quality against the modified AMSTAR tool. Their quality ranged from fair [14, 15, 18, 20] to excellent [16].

Like all systematic reviews, ours is prone to a number of limitations. In fact, our searches were limited to English articles and restricted to a time frame between 2000 and 2014. The review focused on specific treatments only, although breast control treatment strategies have a broader scope, including additionally early detection and diagnosis. The limitations inherent in this review may have resulted in some studies being missed in the literature searches. We also acknowledge the possibility that errors may have been made in the interpretation of the results of the systematic reviews that were reviewed. That being said, it is the authors’ understanding that the guidelines for overview of systematic reviews were adhered to [10].

Concluding remarks

Evidence produced by economic evaluations in general, and in the breast cancer field in particular, have the potential of informing clinical and reimbursement decision-making. The literature contains a plethora of economic evaluations dealing with different aspects of breast cancer treatments. It is therefore, important to ensure that all relevant economic evidence is appropriately synthesized to enable and facilitate reimbursement of potentially valuable treatments by decision-makers. Based on the review of the studies included in the current paper, some recommendations previously published by many authors apply and are recapped here.

The ability for decision-makers to arrive at an appropriate conclusion about the cost-effectiveness of breast cancer treatment strategies could be made easier and more transparent by better harmonizing the reporting of economic evaluations assessing the value of these treatment strategies. Even though some efforts have been made to tackle this issue (e.g., task forces on best practices in reporting the results of economic evaluations from different professional societies, such as the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research), room still exists to improve and strengthen recommendations for standardization in modeling treatment strategies in breast cancer. Doing so will facilitate comparability and consistency of economic evaluations of breast cancer treatments across healthcare jurisdictions worldwide. The stakes are high since providing coverage for a treatment that, in reality, is not cost-effective will result in huge opportunity costs and prevent other patients from accessing alternatives that are potentially valuable. In turn, a policy decision that denies coverage of a treatment that, in reality, is cost-effective will certainly prevent patients from getting access to effective treatments, which itself may result in productivity losses. Future research investigating ways to improve and ensure adherence to guidelines for the reporting of economic evaluations is therefore warranted.

References

National Cancer Institute. (2014) Cancer topics: Breast cancer. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/breast. Accessed 5 Jan 2015. 2015:1–1

Benson JR, Jatoi I (2012) The global breast cancer burden. Future Oncol 8:697–702

Sullivan R, Peppercorn J, Sikora K et al (2011) Delivering affordable cancer care in high-income countries. Lancet Oncol 12:933–980

Arash R, Barfar E, Hosseini H et al (2013) Cost effectiveness of breast cancer screening using mammography; a systematic review. Iran J Public Health 42:347–357

Zelle SG, Baltussen RM (2013) Economic analyses of breast cancer control in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Syst Rev 2:20

Mandelblatt J, Saha S, Teutsch S et al (2003) The cost-effectiveness of screening mammography beyond Age 65 years a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 139:835–842

Okonkwo QL, Draisma G, der Kinderen A et al (2008) Breast cancer screening policies in developing countries: a cost-effectiveness analysis for India. J Natl Cancer Inst 100:1290–1300

Younis T, Skedgel C (2008) Is trastuzumab a cost-effective treatment for breast cancer? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 8(5):433–442

Becker LA, Oxman AD (2008) Overviews of reviews. In: Higgins JP (ed) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley, Chichester, pp 607–631

Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM et al (2011) Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 11:15

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (2011) Grey matters: a practical search tool for evidence-based medicine. Information Services, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Ottawa

Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA et al (2009) AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 62:1013–1020

Gerard K, Seymour J, Smoker I (2000) A tool to improve quality of reporting published economic analyses. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 16:100–110

Ferrusi IL, Leighl NB, Kulin NA et al (2011) Do economic evaluations of targeted therapy provide support for decision makers? Am J Manag Care 17(Suppl 5 Developing):SP61–SP70

Parkinson B, Pearson SA, Viney R (2014) Economic evaluations of trastuzumab in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review and critique. Eur J Health Econ 15:93–112

Lewis R, Bagnall AM, King S et al (2002) The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of vinorelbine for breast cancer: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 6:1–269

John-Baptiste AA, Wu W, Rochon P et al (2013) A systematic review and methodological evaluation of published cost-effectiveness analyses of aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early stage breast cancer. PLoS One 8:e62614

Chan AL, Leung HW, Lu CL et al (2009) Cost-effectiveness of trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy for early breast cancer: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother 43:296–303

Frederix GW, Severens JL, Hovels AM et al (2012) Reviewing the cost-effectiveness of endocrine early breast cancer therapies: influence of differences in modeling methods on outcomes. Value Health 15:94–105

Foster TS, Miller JD, Boye ME et al (2011) The economic burden of metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review of literature from developed countries. Cancer Treat Rev 37:405–415

Benedict A, Brown RE (2005) Review of cost-effectiveness analyses in hormonal therapies in advanced breast cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother 6:1789–1801

Blank PR, Dedes KJ, Szucs TD (2010) Cost effectiveness of cytotoxic and targeted therapy for metastatic breast cancer: a critical and systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics 28:629–647

Norum J (2006) The cost-effectiveness issue of adjuvant trastuzumab in early breast cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother 7:1617–1625

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Julian Renaine, data research librarian at Florida State University, for his help in accessing some databases as part of our literature search. Janet P. Barber, Ph.D., helped edit the final version of the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Rima Tawk and Vassiki Sanogo have contributed equally to this work.

Appendix

Appendix

Search strategies for databases included in the review

See Tables 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Diaby, V., Tawk, R., Sanogo, V. et al. A review of systematic reviews of the cost-effectiveness of hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 151, 27–40 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3383-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3383-6