Abstract

Knowledge of the native range of invasive pests is vital for understanding their biology, for ecological niche modeling to infer potential invasive distribution, and for searching of natural enemies. Standard descriptions of pest ranges frequently pass from one publication to another without verification. Our goal is to test the reliability of distributional information exemplified by the native range of one of the most destructive and most studied invasive forest insect pests of Asian origin—the emerald ash borer (EAB), Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire. Since the first detections of this notorious insect pest in North America in 2002 and European Russia in 2003, it has killed hundreds of millions of ash trees. Based on the examination of museum specimens and literature sources we compiled the most comprehensive database of records (108 localities) and the most detailed map of the native range of EAB in East Asia to date. There are documented records for 87 mainland localities of EAB in the Russian Far East (Primorskiy, Khabarovskiy Kray), China (Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Beijing, Hebei, Tianjin, Shandong and Xinjiang), and South Korea, and 21 localities in Japan. Records from Nei Mongol, Sichuan, Mongolia, and Taiwan are ambiguous since no documented records are available. The example of EAB shows that standard descriptions of pest ranges could include false or ambiguous data. Compilation of the database of documented localities is the only way to obtain reliable information on the range.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Knowledge of the native ranges of invasive pests is of great importance. First, distributional information is crucial for understanding the various aspects of the biology and ecology of the pest. Second, natural enemies of the pest occur throughout its native range and these may be used for biological control. Third, the precise information about the native range, and especially the database of documented localities, form the basis for ecological models and forecasts of the potential invasive distribution of the pest (Sobek-Swant et al. 2012). Publications on certain invasive species usually include a “standard” description of its distribution in the terms of administrative units—countries and provinces in which the species is recorded. These range descriptions frequently pass from one publication to another without critical verification. Our goal is to test the reliability of distributional information based on a re-examination of the native range of one of the most destructive and the most studied forest pests in the world—Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire, 1888.

The emerald ash borer (EAB), Agrilus planipennis native to East Asia is an extremely aggressive invasive insect pest of ash (Fraxinus spp.) (Jendek and Grebennikov 2011; Chamorro et al. 2015). It was first detected in North America in 2002 (Haack et al. 2002) and in European Russia in 2003 (Izhevskii 2007; Volkovitsh 2007) and since then it has killed hundreds of millions of ash trees in both regions (Haack et al. 2015). The economic and environmental impact of the invasion is tremendous (Herms and McCullough 2014). The standard description of the native range is as follows: China: Beijing, Hebei, Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Nei Mongol, Shandong, Sichuan, Tianjin, Xinjiang; Japan: Hokkaido, Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku; North Korea; South Korea; Taiwan; Mongolia; Russia: Far East (Primorskyi Kray) (Hou Tao-qian 1986; Jendek and Grebennikov 2011; Chamorro et al. 2015; EPPO 2017). Samples of distribution maps, based on administrative units, can be found in Chamorro et al. (2015) and Haack et al. (2015).

In the invaded North American range, more than 5000 occurrence records are known (Sobek-Swant et al. 2012), and range expansion is tracked by the website Emerald Ash Borer Info (2017). The EAB invaded range in European Russia is also rather well known with more than 70 occurrence records documented (Straw et al. 2013; Orlova-Bienkowskaja 2013, 2014). However, only limited information is available on the occurrence of EAB in its native range because it is considered a rare species in natural forests (Alexeev 1979; Yurchenko et al. 2007). Distributional information is scattered in many publications, some of them are in Russian, Chinese and Japanese or published in rare, early sources not available on the internet. Distribution maps of EAB within its native range are presented in several papers, but all of them are incomplete since they are based on a relatively small number of precise localities. Liu et al. (2003) and Wei et al. (2004) compiled distribution maps of EAB in China based on 11 and 14 documented localities, respectively. Keever et al. (2013) mapped 8 localities in China and South Korea. Bray et al. (2011) mapped 18 localities in China, South Korea and Japan. Sobek-Swant et al. (2012) adopted localities from Bray et al. (2011), together with some additional information, and compiled a map based on 36 localities in mentioned countries and the Russian Far East. It is the most comprehensive map of EAB occurrence to date.

Very early information on occurrence of EAB in some regions is not reliable because many administrative borders have changed since time of publication. The problem is complicated by a number of unsolved taxonomic questions and the fact that in the southern parts of the range, A. planipennis could be confused with closely related species, particularly with A. tomentipennis Jendek and Chamorro recorded from Laos and Taiwan (Jendek and Chamorro 2012; Chamorro et al. 2015). To verify the EAB distribution in East Asia, we collected all the information available about EAB occurrence records (totaling, 108 points) and re-examined its native range, taking into account these unresolved issues.

Agrilus planipennis was described from China (Fairmaire 1888). The following names are now regarded as synonyms of A. planipennis: Agrilus marcopoli Obenberger, 1930, which type locality is unclear, Agrilus feretrius Obenberger, 1936 described from Taiwan and Agrilus marcopoli ulmi Kurosawa, 1956 described from Japan (Chamorro et al. 2015).

When analyzing the native range of EAB, it is important to consider the host plants and biotopes (native vs. anthropogenic) in which the pest is recorded in specific locations. Under natural conditions, EAB larval feeding is reported mainly on native Fraxinus mandshurica Rupr.; F. chinensis ssp. rhynchophylla (Hance) A. E. Murray (including F. japonica Blume ex K. Koch as its synonym); and occasionally on F. chinensis chinensis Roxb. Throughout its invasive range, as well as in anthropogenic landscapes within its native range, it is recorded on American ash species (F. americana L.; F. nigra Marshall; F. pennsylvanica Marshall; F. quadrangulata Michx.; F. velutina Torr.) and European ash (F. excelsior L.) (Jendek and Grebennikov 2011; Jendek and Poláková 2014; Orlova-Bienkowskaja 2014; Chamorro et al. 2015). Within the invasive range in the USA., larval feeding on another representative of Oleaceae, white fringetree, Chionanthus virginicus L. was recently reported (Cipollini 2015). In Japan A. planipennis has been also reported from Juglans mandshurica var. sieboldiana Maxim.; Pterocarya rhoifolia Siebold and Zucc. (both Juglandaceae); and Ulmus davidiana var. japonica (Rehder) Nakai (Ulmaceae) (Jendek and Grebennikov 2011; Jendek and Poláková 2014), however there is no evidence whether EAB was reared from or only collected on these plants. The only verified larval hosts of EAB are Fraxinus species (Zhao et al. 2005; Jendek and Poláková 2014) and Chionanthus virginicus (Cipollini 2015), both from the family Oleaceae. Native hosts and biotopes are most valuable to outline the native range of EAB, while the regions where the pest occur only on introduced hosts in anthropogenic landscapes, could represent a secondary range.

Methods

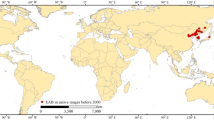

We compiled a database comprising 87 localities of Agrilus planipennis in mainland East Asia and 21 localities in Japan, totaling 108 localities (see electronic supplementary material) and made a detailed map of its native range using the software DIVA-GIS 7.5 (Fig. 1). The sources of information were mainly the specimens deposited in the collections of the Zoological Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences (ZIN; Russia, St. Petersburg), National Museum (NMPC, Prague, Czech Republic) (type specimens of A. marcopoli Obenberger, 1930 and A feretrius Obenberger, 1936); M.Yu. Kalashian (MKCY; Armenia, Yerevan) and S.N. Ivanov (SICV; Russia, Vladivostok), as well as the exact localities from 31 publications (see Table 1). Some localities are still known only from old labels, though many geographical names, administrative divisions, and borders have partly changed since the date of specimen collection. Therefore, a significant part of the work was the interpretation of old geographical labels.

Range of EAB in East Asia. 1, 2, 3—native range, type locality and other documented localities of A. planipennis in mainland Asia; 4—ambiguous type locality of A. marcopoli; 5—region in Xinjiang, where A. planipennis was discovered in 2016; 6, 7—ambiguous records of A. planipennis; 8 —the range of A. planipennis in Japan; 9—type locality of A. marcopoli ulmi (synonym of A. planipennis); 10—other documented localities of A. planipennis in Japan; Kh—Khabarovskiy Kray, P—Primorskiy Kray, Hei—Heilongjiang, J—Jilin, L—Liaoning, B—Beijing, Heb—Hebei, T—Tianjin, Sh—Shandong, Xi—Xinjiang, Si—Sichuan, NM—Nei Mongol. Sources of information are listed in Table 1

To obtain additional information on the EAB localities in the Russian Far East, we requested the curators of the largest Russian Coleoptera collections to check for the presence of specimens of EAB in their corresponding collections. There were no specimens in the collections of Zoological Museum of Moscow State University (ZMUM; A.A. Gusakov, personal communication), Moscow State Pedagogical University (MSPU; K.V. Makarov, personal communication), and Siberian Zoological Museum (Coleoptera collection of Siberian Zoological Museum 2017). Only 8 specimens of EAB collected by G.I. Yurchenko on Fraxinus pennsylvanica in Khabarovsk in 2008 were found in the collection of the Federal Scientific Centre of Biodiversity of Terrestrial Biota of East Asia, Far East Department of Russian Academy of Sciences (FSCB; Russia, Vladivostok) (S.A. Shabalin, personal communication).

Results

Documented records

Records based on exact localities of A. planipennis are listed in the Table 1; occurrence points are documented in the database (see electronic supplementary material) and mapped in Figs. 1, 2, 3.

Russian Far East

Prior to the beginning of this century, EAB was exceptionally rare in the forests of the Russian Far East, as evidenced by its rarity in most Coleoptera collections (see "Methods" section). Under natural conditions it feeds on native ash species Fraxinus mandshuric a and F. chinensis rhynchophylla, but it has never been considered a pest, since it affects only weakened trees (Yurchenko et al. 2007). No outbreaks in the natural ash stands have been reported (Yurchenko 2016). The outbreaks have been recorded in urban plantations on Fraxinus pennsylvanica only recently. Cultivation of F. pennsylvanica in the Far East started in the early 1950s. At first, plantations of this ash species existed in the arboretum of Gornotaezhnaya station of Academy of Sciences of the USSR (Primorskiy Kray) (Flora USSR 1952) and in the Far East Forestry Research Institute arboretum (Khabarovskiy Kray) (Yurchenko 2009). Then, in the 1950s–1980s, F. pennsylvanica was widely cultivated in urban plantations in Far East cities. Currently, the plantations of F. pennsylvanica in Vladivostok, Khabarovsk and other cities of Primorskiy and Khabarovskiy Krays are severely damaged by EAB (Yurchenko 2016). All these points of occurrence are shown in Fig. 2 (green and red circles in Primorskiy and Khabarovskiy Krays).

Outbreaks of Agrilus planipennis within its native range. 1—outbreak points (1964—outbreak on Fraxinus americana in Harbin; 1982 and 1998—outbreaks on F. velutina in Tianjin; ~ 2000—outbreaks on F. pennsylvanica in Vladivostok and Khabarovsk); 2, 3—range and points of occurrence of A. planipennis in mainland Asia; 4, 5—range and points of occurrence of A. planipennis (= A. marcopoli ulmi) in Japan. Sources of information are listed in Table 1

Agrilus planipennis was first collected in the Far East in 1935 (Yurchenko et al. 2007) but first recorded for the Russian fauna in 1979 (as A. marcopoli Obenberger) (Alexeev 1979). Only a few specimens were collected in the Far East before 2004 in six districts of Primorskiy Kray: Hasan, Spassk, Shkotovo, Lazo, Ternei and Chuguevka Districts (Alexeev 1979; Jendek 1994; Yurchenko et al. 2007; Jendek and Grebennikov 2011; examined specimens from ZIN, MKCY, SICV). Then, in 2004–2012, special surveys revealed EAB damaging introduced F. pennsylvanica all over Primorskiy Kray and also in the south of Khabarovskiy Kray (Yurchenko 2009; Belokobylskij et al. 2012; Duan et al. 2012; Yurchenko et al. 2007, 2010, 2013a, b).

In 2010 and 2011 the survey of plantations of ash trees in Sakhalin Island did not reveal the presence of EAB (Yurchenko 2016). It also has not been found in Kuril Islands (M.Yu. Proschalykin, personal communication).

China

In China, as in the Russian Far East, EAB does not pose a serious threat to natural ash stands or plantations attacking mainly ornamental trees in urban landscapes. Documented records are known from Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Beijing, Hebei, Tianjin, Shandong and Xinjiang (see Table 1, Fig. 1 and electronic supplementary material). Localities of severe outbreaks are indicated in the map in Fig. 2).

In Heilongjiang A. planipennis was a very rare species until the 1960s. The first outbreak was recorded in Harbin in 1964 on Fraxinus americana introduced from America (Wei et al. 2004). The damage to plantation of Northeast Forestry University Experimental Forest was so severe that the entire plantation was removed. In the course of surveys in 2003–2008, EAB was recorded in four prefectures of Heilongjiang on its native host plants Fraxinus mandshurica and F. chinensis rhynchophylla (Liu et al. 2003; Wei et al. 2004; Bray et al. 2011; Keever et al. 2013). Jendek and Grebennikov (2011) indicated that a specimen with the label “Primorsk 13.8.1935 Mai He [river]” was collected in Heilongjiang, but actually Mai He river (currently, Artiomovka river) is located in Primorskiy Kray, Russia. EAB is recorded in at least five prefectures of Jilin province on F. mandshurica, F. chinensis rhynchophylla, and F. pennsylvanica, and at least in six prefectures of Liaoning province on F. mandshurica, F. chinensis rhynchophylla, and F. chinensis chinensis (Hou Tao-qian 1986; Wei et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2003, 2007; Bray et al. 2011).

In Beijing Agrilus planipennis is known from the late 19th century, since it is a type locality of the species (Fairmaire 1888). Now it is rather common in this region and in the adjacent provinces of Hebei and Tianjin on native Fraxinus chinensis rhynchophylla, F. chinensis chinensis, and the non-native (introduced from North America) F. velutina, though before the introduction of the later it was rather rare there (Li Zhong 2002; Liu et al. 2003; Bray et al. 2011; Jendek and Grebennikov 2011; Chamorro et al. 2015). Fraxinus velutina was imported to Tianjin in 1952 and to Beijing in 1956 (Wei et al. 2004). In Tianjin city EAB was first recorded in 1982 on a plantation of F. velutina (Wei et al. 2004). The efforts to control the outbreak failed and all infested trees were cut down in 1991. In 1993 F. velutina was planted in Guangang District of Tianjin and severe damage by EAB was observed in 1998–2002. During surveys in 2003–2008, A. planipennis was found in at least six localities in Tianjin on F. velutina and F. pennsylvanica (Liu et al. 2003; Wei et al. 2004; Bray et al. 2007, 2011). The outbreaks were also recorded in Hebei (Wei et al. 2004).

In the province of Shandong, the southernmost documented EAB localities in mainland China, it occurs on F. velutina in urban plantations (Wei et al. 2004). Based on the introduced host, it may be suggested that localities in Shandong belong to the introduced range after EAB’s primary range expansion followed the outbreaks in Tianjin in 1982 and 1998 (Fig. 2) (Fuester and Schaefer 2006).

EAB is also recorded in the north-west part of China in Xinjiang Autonomous region (Wei et al. 2004). According to Zhaozhi Lu (personal communication), in 2016, EAB was found in Yili valley. The distribution map of F. mandshurica (Fig. 3) shows that this ash species can reach the westernmost limits of Xinjiang. Additionally, another ash species, F. angustifolia syriaca (Boiss) Yalt. (= F. sogdiana Bunge), occurs in western Xinjiang and adjacent regions of Kazakhstan (Flora of China 2017). The recent detection of emerald ash borer in Xinjiang should be treated as a new invasion by the pest, rather an expansion of the pest’s native range.

Ranges of the native host plants of Agrilus planipennis in East Asia. 1—Fraxinus mandshurica, 2—F. mandshurica + F. chinensis (F. chinensis chinensis and F. chinensis rhynchophylla), 3—F. chinensis, 4—points of occurrence of A. planipennis in mainland Asia, 5—points of occurrence of A. planipennis in Japan. Sources of information on ranges of Fraxinus species: Cleary et al. (2016), GBIF (2017). Sources of information for EAB points of occurrence are listed in Table 1

Korean peninsula

EAB is known from Korea at least since 1943 (Kurosawa 1956). Special surveys made in 2003–2008 have shown that EAB is widespread there but occurs at low densities and feeds mainly on Fraxinus chinensis rhynchophylla and F. mandshurica (Ko Je Ho 1969; Williams et al. 2006, 2010; Bray et al. 2007, 2011; Keever et al. 2013). All documented localities are from South Korea, but there is no doubt that the species also occurs in North Korea because this region is situated in the center of the known range of the species (EPPO 2017).

Japan

Records of EAB from Japan are based on the assumption that Agrilus marcopoli ulmi is a synonym of A. planipennis (Table 1, Figs. 1, 2). In 1956 A. marcopoli ulmi, with the host plant Ulmus propinqua (= davidiana var. japonica according to Jendek and Poláková 2014), was described from Sapporo, Japan based of specimens collected in 1930 (Kurosawa 1956). Jendek (1994) synonymized A. marcopoli ulmi with A. planipennis, but Akiyama and Ohmomo (1997) treated it as a distinct subspecies and indicated that its host plants are Ulmus divadiana var. japonica; Pterocarya rhoifolia; Juglans mandshurica var. sieboldiana (= ailanthifolia according to Jendek and Poláková 2014); Fraxinus mandshurica var. japonica. However, it is unclear if the specimens examined by these authors were reared from the mentioned plants or just collected on them. Bray et al. (2011) established that the mtDNA haplotype from a single adult specimen collected in Japan strongly differed from all the A. planipennis collected in Asia and North America. Thus, the presence of the emerald ash borer in Japan has been doubted by some authors (Herms and McCullough 2014). However, the identity of A. planipennis and A. marcopoli ulmi was currently confirmed by E. Jendek who claims that there are no reliable morphological features allowing the separation of mainland and Japanese specimens even at a subspecific level (E. Jendek, personal communication of June 2017).

Ambiguous records

Mongolia

The occurrence of EAB in Mongolia is cited in hundreds of publications (e.g. Ko Je Ho 1969; Hou Tao-qian 1986; Jendek 1994; Li Zhong 2002; Jendek 2006; Jendek and Grebennikov 2011; Duan et al. 2012; Chamorro et al. 2015). But all these records actually refer to a single locality, namely the type locality of Agrilus marcopoli Obenberger, 1930, which is the junior synonym of A. planipennis (Jendek 1994). The lectotype of A. marcopoli bears the label “Mongol. or.: Chan-heou” (lectotype: NMPC). It is difficult to determine where this geographical point is situated. According to the catalogue of Carabus collecting localities in China, “Chan-heou” is situated in Hebei (China) (40.38 N, 117.41 E) (Schütze, Kleinfeld 2007). According to E. Jendek (personal communication), the name “Chan-heou” refers to the settlement Cha-hen-hua (currently Ujimqin) on Shiliin (Xilin) Gol river (46.63 N, 119.52 E), which is situated in Nei Mongol (China) near the Mongolian border (Google maps 2017). Therefore, the exact position of the type locality of A. marcopoli is not clear, but some authors believe that it is situated in China rather than in Mongolia (e.g. Schaefer 2004). In 2003, Schaefer traveled to Mongolia looking for A. planipennis but did not find it. Mongolian entomologists with whom he has consulted, said that EAB does not occur in this country (Schaefer 2004). Additionally, neither the genus Fraxinus, nor the family Oleaceae are reported from Mongolia (Grubov 1955, 1982; Urgamal 2014). Therefore, according to the information available to date, there is no reason to believe that EAB occurs in Mongolia.

Nei Mongol (Inner Mongolia) (China)

Nei Mongol is regarded to be a part of the native range of EAB in many sources (Hou Tao-qian 1986; Yu 1992; Jendek 1994; Nonnaisab et al. 1999; Li Zhong 2002; Wei et al. 2004; Jendek and Grebennikov 2011; Chamorro et al. 2015), but no documented localities are available. Jendek and Grebennikov (2011) indicated that two specimens labelled "Chahar Yangkiaping 8–10.VII.1937” were collected in Nei Mongol. But monastery Yangkiaping is situated in the historical region Chahar, currently in Hebei (Yan et al. 2013). Additionally, it is not excluded that the type locality of Agrilus marcopoli, “Chan-heou”, is really situated in Nei Mongol (see above). However, the special survey in Nei Mongol in 2006 did not reveal this species in the region (Wang et al. 2010). The host plant Fraxinus mandshurica has very restricted distribution in Nei Mongol (Cleary et al. 2016), but occurs just in the region, which is supposed to be the type locality of A. marcopoli (Fig. 3).

Sichuan (China)

The record of EAB from Sichuan is based on a single old specimen from the National Museum in Prague (Czech Republic) labelled “Szechuan” without any additional information (Jendek 1994). The origin of this specimen is unknown, and it cannot be excluded that this geographic label is incorrect. According to Wei et al. (2004), the host plant Fraxinus chinensis, occurs in this province, but EAB was not found nether in Sichuan nor in adjacent provinces of China. This region is situated more than 1000 km south-west from the nearest documented locality of EAB.

Taiwan

There are only two old records of EAB from Taiwan. Firstly, Agrilus feretrius Obenberger, 1936 (lectotype: NMPC), which is a junior synonym of A. planipennis (Jendek 1994), was described from “Formosa” (old name of Taiwan). Secondly, Schaefer (2004) examined specimen(s) of A. feretrius (as A. teretrius) from Taoyuan Province of Taiwan in the collection of Kurosawa (National Museum, Tokyo) and concluded that the later treated A. feretrius as a subspecies of A. marcopoli (= A. planipennis) though he has never validated this status. Herms and McCullough (2014) doubted the presence of EAB in Taiwan, since the records could refer to another species and we agree with this point of view. First, Taiwan is situated far to the south of all other known localities of EAB. Second, there are at least two closely related species from the same species group reported from Taiwan: A. tomentipennis Jendek and Chamorro 2012 and A. pseudolubopetri Jendek and Chamorro 2012 (Chamorro et al. 2015). Additionally, though two species of Fraxinus are widely distributed in Taiwan (Flora of Taiwan 1998), these are not indicated as host-plants for EAB.

Laos

Agrilus planipennis was reported from Laos (Jendek and Grebennikov 2011). However, later it was established that this record referred to the closely related A. tomentipennis from the same species-group (Jendek and Chamorro 2012; Chamorro et al. 2015).

Discussion

Careful re-examination of the native range of A. planipennia has shown, that the reliable range is much more restricted than it is usually described in literature. There is no doubt that A. planipennis occurs in the Far East of Russia (Khabarovskiy Kray, Primorskiy Kray); China (Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Beijing, Hebei, Tianjin, Shandong, Xinjiang), and the Korean peninsula. Each of these records is confirmed by several independent sources of information, occurrence records are well documented and the identification of the species is reliable. From a biogeographical viewpoint, the bulk of the native range of EAB is within the Stenopean (Manchurian–Northern-Chinese–Northern-Japanese) nemoral region and areas transitional to adjacent regions of the Palaearctic part of East Asia (Emeljanov 1974; Konstantinov et al. 2009). Over a great extent, it also overlaps with the eastern part of the range of the manchurian ash (Fraxinus mandshurica Rupr.) (Fig. 3), which is one of the principal EAB host plants. Thus, EAB can be characterized as a mostly nemoral species. This is also confirmed by the location and extent of invasive ranges of EAB in North America and European Russia (see Chamorro et al. 2015). At the same time, taking into account the anthropogenic factor (the presence of urban plantations in populated areas) and the possibility of spreading ash trees along the river valleys (which can explain some remote isolated locations of the pest), the EAB range may extend far beyond the nemoral zone (e.g., location in Xinjiang) forming satellite colonies at the periphery of the main range as it is observed, for example, in its invasive area in European Russia (Orlova-Bienkowskaja 2013, 2014) and North America (Siegert et al. 2014).

In this regard, it is unknown if the entire modern range of A. planipennis in East Asia is native (primary range) or it has partly expanded as a result of transition of the pest to the cultivated American ashes (secondary range). Because humans plant trees wherever they choose, pests often take advantage of new host sources, ranging far outside their ancestral home to invade the new plantings (Fuester and Schaefer 2006). Such cases are rather common among coleopteran species. For example, Agrilus convexicollis expanded its range into European Russia because of the mass cultivation of alien Fraxinus pennsylvanica and because of drastic weakening of its plantations as a result of the invasion of EAB (Orlova-Bienkowskaja and Volkovitsh 2014). It can be assumed that the transition from resistant native to non-resistant introduced American ash species (most commonly F. pennsylvanica) triggered the pest outbreaks (Fig. 2) and led to a significant expansion of the primary range (Khabarovsk in Russia, Shandong and, possibly, Xinjiang in China). Moreover, this transition followed by outbreaks can be regarded as an initial phase of subsequent invasion of the EAB beyond East Asia.

It seems that just the outbreaks of EAB in Tianjin and Hebei were the initial point of further invasion of the pest to North America and European Russia. First, EAB has been a rare species in native forests, so the probability of invasion of the pest from regions other than regions of outbreaks is vanishingly small, since high propagule pressure is necessary to overwhelm the ecological resistance of the community (Holle and Simberloff 2005). Second, the time of the outbreaks in China coincides with the estimated time of invasion: it is assumed that EAB was unintentionally introduced to North America and European Russia in the early 1990s (Siegert et al. 2014; Straw et al. 2013). Third, genetic research by Bray et al. (2011) has revealed that North American populations are most closely related to populations from the Chinese province of Hebei and Tianjin City. Moreover, this region is an important center of Chinese export, where goods from this region are exported all over the world. Unintentional introduction with exported goods could be the vector of EAB invasion.

EAB is one of the most popular research subjects in the fields of forest entomology, invasion biology, plant protection, urban ecology, etc. over the past 15 years. According to Google Scholar, about 100 scientific publications dealing with this notorious pest are published each year. But, despite the great interest to EAB after its invasion of North America and European Russia, its native range was poorly known. The majority of the publications that mention EAB distribution include unverified information from earlier sources. False or ambiguous records of species distribution sometimes occur because of misidentifications, taxonomic problems and unclear labels result in incorrect interpretations of geographic data. The same concerns arise with some other invasive organisms (Orlova-Bienkowskaja et al. 2015). The example of EAB shows that standard descriptions of native ranges of invasive pests, repeated in hundreds of books and articles, could be unreliable. Careful examination of range based on collection of data on precise locations is the only way to compile a reliable description. are still unresolved.

References

Akiyama Y, Akiyama K (1996) The Buprestid beetles (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) from Hiroshima Prefecture, southwestern Japan. Misc Rep Hiwa Mus Nat Hist 34:181–192 (in Japanese)

Akiyama K, Ohmomo S (1997) A checklist of the Japanese Buprestidae. Gekkan-Mushi (Supplement 1), Tokyo. pp. 67

Alexeev AV (1979) New, previously unknown from the territory of the USSR, and little-known species of jewel-beetles (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) of Eastern Siberia and the Far East. In: Krivolutskaya GO (ed) Beetles of the Far East and Eastern Siberia (new data on the fauna and taxonomy). Far East Scientific Center of Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Vladivostok, pp 123–139 (in Russian)

Belokobylskij SA, Yurchenko GI, Strazanac JS, Zaldivar-Riveron A, Mastro V (2012) A new emerald ash borer (Coleoptera, Buprestidae) parasitoid species of Spathius Nees (Hymenoptera: Braconidae: Doryctinae) from the Russian Far East and South Korea. Ann Entomol Soc Am 105:165–178. https://doi.org/10.1603/AN11140

Bray AM, Bauer LS, Fuester RW, Choo HY, Lee DW, Kamata N, Smith JJ (2007) Expanded explorations for emerald ash borer in Asia and implications for genetic analysis. Emerald Ash Borer and Asian Longhorhed Beetle research and technology development meeting. Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, West Virginia, pp 6–7

Bray M, Bauer LS, Poland TM, Haack RA, Cognato AI, Smith JJ (2011) Genetic analysis of emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire) populations in Asia and North America. Biol Invasions 13:2869–2887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-011-9970-5

Chamorro ML, Jendek E, Haack RA, Petrice TR, Woodley NE, Konstantinov AS, Volkovitsh MG, Yang X-K, Grebennikov VV, Lingafelter SW (2015) Illustrated guide to the emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire and related species (Coleoptera, Buprestidae). Pensoft, Sofia-Moscow

Cipollini D (2015) White fringetree as a novel larval host for emerald ash borer. J Econ Entomol 108(1):370–375. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tou026

Cleary M, Nguyen D, Marčiulynienė D, Berlin A, Vasaitis R, Stenlid J (2016) Friend or foe? Biological and ecological traits of the European ash dieback pathogen Hymenoscyphus fraxineus in its native environment. Sci Rep 6:21895. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21895

Coleoptera collection of Siberian Zoological Museum (2017) http://szmn.eco.nsc.ru/Coleop/Coleopt.htm. Accessed 10 Apr 2017

Duan JJ, Yurchenko G, Fuester R (2012) Occurrence of emerald ash borer (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) and biotic factors affecting its immature stages in the Russian Far East. Environ Entomol 41(2):245–254. https://doi.org/10.1603/EN11318

Emeljanov AF (1974) Proposals on the classification and nomenclature of areals. Entomologicheskoe Obozrenie 53(3):497–522 (in Russian)

Emereld Ash Borer Info (2017) http://www.emeraldashborer.info. Accessed 10 Apr 2017

EPPO (2017) EPPO plant quarantine data retrieval system. Version 5.3.5. http://www.eppo.int/DATABASES/pqr/pqr.htm. Accessed 10 Apr 2017

Fairmaire L (1888) Notes sur les Coléoptères des environs de Pékin (2e Partie). Rev Entomol (Caen) 7:111–160

Flora USSR (1952) Fam. CXXIX. Oleaceae. In: BK Shishkin, EG Bobrov (eds) Flora of the USSR. Vol. 18. (Primulales: Primulaceae—Ebenales: Asclepiadaceae). Academy of Science of the USSR, Moscow—Leningrad, pp. 483–525 (in Russian)

Flora of China (2017) http://efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=2&taxon_id=210000562. Accessed 06 Apr 2017

Flora of Taiwan (1998) Second edition. Volume Four. Angiosperms—Dicoledons [Diapensiaceae—Compositae]. Taipei Taiwan: Editorial Committee of the Flora of Taiwan

Fuester RW, Schaefer PW (2006) Research on parasitoids of buprestids in progress at the ARS beneficial insect introduction research unit. In V Mastro, D Lance, R Reardon, G Parra (eds) Proceedings of the Emerald Ash Borer and Asian Longhorned Beetle Research and Technology Development Meeting, Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, West Virginia, pp. 53–55

GBIF(2017) GBIF.org (29th March 2017) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.w40ocd, GBIF.org (29th March 2017) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.ydkkwi, GBIF.org (29th March 2017) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.gec4bv GBIF.org (31st March 2017) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.fxnxbx

Google maps (2017) https://www.google.ru/maps. Accessed 06 Apr 2017

Grubov VI (1955) Conspectus of the flora of Mongolian People Republic. Proceedings of Mongolian Comission, 67, Academy of Science of the USSR. Leningrad (in Russian)

Grubov VI (1982) Key to the vascular plants of Mongolia. Nauka, Leningrad (in Russian)

Haack RA, Jendek E, Liu H, Marchant KR, Petrice TR, Poland TM, Ye H (2002) The Emerald Ash Borer: a new exotic pest in North America. Newsl Mich Entomol Soc 47(3 & 4):1–5

Haack RA, Baranchikov Y, Bauer LS, Poland TM (2015) Chapter 1: Emerald ash borer biology and invasion history. In: Van Driesche RG, Reardon RC (eds) Biology and control of emerald ash borer. United States Department of Agriculture, Morgantown, pp 1–15

Herms DA, McCullough DG (2014) Emerald ash borer invasion of North America: history, biology, ecology, impacts, and management. Annu Rev Entomol 59:13–30. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162051

Holle BV, Simberloff D (2005) Ecological resistance to biological invasion overwhelmed by propagule pressure. Ecology 86(12):3212–3218

Hou T-Q (1986) Buprestidae. In: Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, editor. Agricultural Insects of China (Part A). Agriculture Press, China, pp. 438–447 (in Chinese)

Izhevskii SS (2007) Threatening findings of the emerald ash borer Agrilus planipennis in the Moscow region. http://www.zin.ru/Animalia/Coleoptera/rus/agrplaiz.htm. Accessed 10 Apr 2017 (in Russian)

Jendek E (1994) Studies in the east palaearctic species of the genus Agrilus Dahl, 1823 (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) Part I. Entomol Probl 25(1):9–24

Jendek E (2006) Genus Agrilus. In: Lobl I, Smetana A (eds) Catalogue of palaearctic coleoptera, vol 3. Apollo Books, Stenstrup, pp 388–403

Jendek E, Chamorro ML (2012) Six new species of Agrilus Curtis, 1825 (Coleoptera, Buprestidae, Agrilinae) from the Oriental Region related to the emerald ash borer, A. planipennis Fairmaire, 1888 and synonymy of Sarawakita Obenberger, 1924. ZooKeys 239:71–94. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.239.3966

Jendek E, Grebennikov V (2011) Agrilus (Coleoptera, Buprestidae) of East Asia. Jan Farkac, Prague

Jendek E, Polákova J (2014) Host plants of world Agrilus (Coleoptera, Buprestidae). A critical review. Springer, Dordrecht

Keever CC, Nieman C, Ramsay L, Ritland CE, Bauer LS, Lyons DB, Cory JS (2013) Microsatellite population genetics of the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire): comparisons between Asian and North American populations. Biol Invasions 15(7):1537–1559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-012-0389-4

Ko Je Ho (1969) A list of forest insect pests in Korea. Forest Research Institute, Seoul

Konstantinov AS, Korotyaev BA, Volkovitsh MG (2009) Chapter 7. Insect biodiversity in the palearctic region. In: Foottit RG, Adler PH (eds) Insect biodiversity: science and society. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, pp 107–162

Kurosawa Y (1956) Buprestid-fauna of Eastern Asia (3). Bull Natl Sci Mus, Tokyo, N.S. 3(38):33–41

Li Zhong H (2002) List of Chinese insects. Vol. II. Zhongshan (Sun Yat—sen) University Press, Guangzhou

Liu HP, Bauer LS, Gao R, Zhao T, Petrice TR, Haack RA (2003) Exploratory survey for emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) and its natural enemies in China. The Great Lakes Entomol 36:191–204

Liu HP, Bauer LS, Miller DL, Zhao TH, Gao RT, Song L, Luan Q, Jin R, Gao C (2007) Seasonal abundance of Agrilus planipennis (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) and its natural enemies Oobius agrili (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) and Tetrastichus planipennisi (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) in China. Biol Control 42:61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2007.03.011

Nonnaizab NA, Qi B, Li Y (1999) Insects of inner mongolia china. People’s Publishing House in Inner Mongolia, Hu He Hao Te (in Chinese)

Orlova-Bienkowskaja MJ (2013) Dramatic expansion of the range of the invasive ash pest, buprestid beetle Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire, 1888 (Coleoptera, Buprestidae) in European Russia. Entomol Rev 93(9):1121–1128. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0013873813090042

Orlova-Bienkowskaja MJ (2014) Ashes in Europe are in danger: the invasive range of Agrilus planipennis in European Russia is expanding. Biol Invasions 16(7):1345–1349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-013-0579-8

Orlova-Bienkowskaja MJ, Volkovitsh MG (2014) Range expansion of Agrilus convexicollis in European Russia expedited by the invasion of emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis (Coleoptera: Buprestidae). Biol Invasions 17:537–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-014-0762-6

Orlova-Bienkowskaja MJ, Ukrainsky AS, Brown PMJ (2015) Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in Asia: a re-examination of the native range and invasion to southeastern Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Biol Invasions 17(7):1941–1948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-015-0848-9

Schaefer PW (2004) Agrilus planipennis (A. marcopoli) (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) in Japan and Mongolia—preliminary findings. In: Mastro V, Reardon R (eds) Emerald ash borer research and technology development meeting, 30. FHTET, Morgantown, p 13

Schütze H, Kleinfeld F (2007) Neuauflage. Die Caraben Chinas. Systematic—alle Taxa—Bibliographie—Lexicon aller literaturbekannten Fundorte. 3. völlig überarbeite Auflage. Delta-Druck + Verlag, Peks, Schwanfeld

Siegert NW, McCullough DG, Liebhold AM, Telewski FW (2014) Dendrochronological reconstruction of the epicentre and early spread of emerald ash borer in North America. Divers and Distrib 20:847–858. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12212

Sobek-Swant S, Kluza DA, Cuddington K, Lyons DB (2012) Potential distribution of emerald ash borer: what can we learn from ecological niche models using Maxent and GARP? For Ecol Manag 281:23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2012.06.017

Straw NA, Williams DT, Kulinich O, Gninenko YI (2013) Distribution, impact and rate of spread of emerald ash borer Agrilus planipennis (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) in the Moscow region of Russia. Forestry 86:515–522. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpt031

Urgamal M, Oyuntsetseg B, Nyambayar D, Dulamsuren Ch (2014) Conspectus of the vascular plants of Mongolia. Sanchir Ch. Jamsran Ts (eds) “Admon“Press, Ulaanbaatar

Volkovitsh MG (2007) Emerald ash borer Agrilus planipennis—new extremely dangerous pest of ash in the European part of Russia. http://www.zin.ru/Animalia/Coleoptera/rus/ eab_2007.htm. Accessed 10 Apr 2017 (in Russian)

Volkovitsh MG (2009) Buprestidae. In: Storozhenko SY (ed) Insects of lazovsky nature reserve. Dalnauka, Vladivostok, pp 132–137 (in Russian)

Wang XY, Yang ZQ, Gould JR, Zhang YN, Liu GJ, Liu ES (2010) The biology and ecology of the emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis. China J Insect Sci 10(128):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1673/031.010.12801

Wang XY, Cao LM, Yang ZQ, Duan JJ, Gould JR, Bauer LS (2016) Natural enemies of emerald ash borer (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) in northeast China, with notes on two species of parasitic Coleoptera. Can Entomol 148(3):329–342. https://doi.org/10.4039/tce.2015.57

Wei X, Reardon D, Yun W, Sun JH (2004) Emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire (Coleoptera: Buprestidae), in China: a review and distribution survey. Acta Entomol Sinica 47:679–685

Wei X, Wu Y, Reardon R, Sun T-H, Lu M, Sun JH (2007) Biology and damage traits of emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire) in China. Insect Sci 14:367–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7917.2007.00163.x

Williams D, Lee H-P, Jo Y-S (2006) Exploration for emerald ash borer and its natural enemies in South Korea during May–June 2005. In: V Mastro, D Lance, R Reardon, G Parra (eds) Proceedings of the Emerald Ash Borer and Asian Longhorned Beetle Research and Technology Development Meeting, Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, West Virginia, p 52

Williams D, Lee HP, Jo YS, Yurchenko GI, Mastro VC (2010) Exploration for emerald ash borer and its natural enemies in South Korea and the Russian Far East 2004–2009. In: D Lance, J Buck, D Binion, R Reardon, V Mastro (eds) Proceedings of the Emerald Ash Borer and Asian Longhorned Beetle Research and Technology Development Meeting, Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, West Virginia, pp. 94–95

Yan CJ, He JH, Chen XX (2013) The genus Brulleia Szépligeti (Hymenoptera, Braconidae, Helconinae) from China, with descriptions of four new species. ZooKeys 257:17–31. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.257.3832

Yu C (1992) Agrilus marcopoli obenberger. In: Xiao G (ed) Forest Insects of China, 2nd edn. China Forestry Publishing House, Beijing, pp 400–401 (in Chinese)

Yurchenko GI (2009) About ash-trees and emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire) in Khabarovsk and its vicinity. In: Far Eastern forests condition and actual problems of forest management. Materials of all-Russian conference with international participation, FEFRI, Khabarovsk, pp. 289–292 (in Russian)

Yurchenko GI (2010) Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire on natural and introduced ashes in southern part of Far East. News of the Saint Petersb State For Tech Acad 192:269–276 (in Russian)

Yurchenko GI (2016) Emerald ash borer in Russian Far East. In: Gninenko Yu (ed) Emerald ash borer—occurrence and protection operatiobns in the USA and Russia. Pushkino, VNIILM, pp 5–10 (in Russian)

Yurchenko GI, Turova GI, Kuzmin EA (2007) To distribution and ecology of emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire) in the Russian Far East. In: AI Kurentsov’s Annual Memorial Meetings, 18, pp. 94–98 (in Russian)

Yurchenko GI, Williams DW, Kuzmin EA (2013a) Monitoring of populations of Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire) and its parasitoids in the south part of Russian Far East. In: Far Eastern forests condition and actual problems of forest management. «Dal’NIILKh» , Khabarovsk, pp 440–444 (in Russian)

Yurchenko GI, Kuzmin EA, Burde PB (2013b) Biology of the Emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire) and its parasitoids in the south part of Prinorskii krai. AI Kurentsov’s Annual Memorial Meetings, 24, Dal’nauka, Vladivostok. pp. 174–178 (in Russian)

Zhang YZ, Huang DW, Zhao TH, Liu HP, Bauer LS (2005) Two new species of egg parasitoids (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) of wood-boring beetle pests from China. Phytoparasitica 53:253–260

Zhao TH, Gao RT, Liu HP, Bauer LS, Sun LQ (2005) Host range of emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire, its damage and the countermeasures. Acta Entomol Sinica 48(4):594–599 (in Chinese with English summary)

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by Russian Science Foundation, Project No 16-14-10031. We would like to thank E. Jendek (Bratislava, Slovakia) for the valuable information and comments on EAB distribution and providing us with missing literature; we are also grateful to V. Kubàň (Šlapanice near Brno, Czech Republic), G. I. Yurchenko (The Far East Forest Research Institute, Forest Management Agency of the Russian Federation, Khabarovsk, Russia), Zhaozhi Lu (Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences), and M. Yu. Proschalykin (FSCB) for valuable information used in this paper; to M. Yu. Kalashian (Institute of Zoology, Scientific Center of Zoology and Hydroecology, National Academy of Sciences of Armenia, Yerevan, Armenia), and S. N. Ivanov (private collector, Vladivostok, Russia) for providing the exact locations for EAB specimens in their collections for this study; to A. A. Gusakov (ZMUM), K. V. Makarov (MSPU), and S. A. Shabalin (FSCB) for checking the presence of EAB specimens in corresponding collections.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Orlova-Bienkowskaja, M.J., Volkovitsh, M.G. Are native ranges of the most destructive invasive pests well known? A case study of the native range of the emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis (Coleoptera: Buprestidae). Biol Invasions 20, 1275–1286 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-017-1626-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-017-1626-7