Abstract

Emerald ash borer (EAB), Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire (Coleoptera: Buprestidae), is an invasive pest of North American ash (Fraxinus spp.) trees first discovered outside of its native range of northeastern Asia in 2002. EAB spread from its initial zone of discovery in the Detroit, Michigan and Windsor, Ontario metropolitan areas, in large part, from inadvertent human-assisted movement of infested ash materials. EAB infestations are now known in 15 US states and two Canadian provinces. The primary goal of this study was to use molecular markers to characterize the population genetic structure of EAB in its native and introduced range. This information may provide valuable insights on the geographic origin, potential host range, invasion potential, and additional biological control agents for ongoing management efforts of this destructive wood-boring beetle. EAB were collected from 17 localities in its native Asian range and from 7 localities in North America, and population structure analyzed using mtDNA gene sequences, AFLP fingerprints, and alleles at 2 microsatellite loci. Analysis of mtDNA cytochrome oxidase subunit I gene (COI; 439 bp) sequences revealed all North American individuals carry a common mtDNA haplotype also found in China and South Korea. Additional mtDNA haplotypes observed in China and South Korea differed from the common haplotype by 1–2 nucleotide substitutions and a single individual from Japan differed by 21 nucleotide changes (4.8%). Analysis using AFLP fingerprints (108 loci) indicated Asian populations were more highly variable, yet had less overall population structure, than the North American populations. North American populations appear most closely related to populations in our sample from the Chinese provinces of Hebei and Tianjin City. Further, population assignment tests assigned 88% of the individual beetles from North America to either Hebei or Tianjin City.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The United States and Canada are currently battling infestations of emerald ash borer (EAB), Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire (Coleoptera: Buprestidae), a destructive Asian pest of ash (Fraxinus spp.) trees. EAB is native to areas of northeastern Asia and was first detected in North America in 2002, initially being found in southeastern Michigan (Detroit area), and adjacent southeastern Ontario (Windsor area) (Haack et al. 2002). It is suspected that EAB was introduced to North America in the early to mid-1990s (Siegert et al. 2010). As of August 2010, the North American range of EAB includes 15 US states and the provinces of Ontario and Quebec, Canada (USDA-APHIS 2010).

EAB is native to northeastern Asia including portions of China, Japan, Korea, Mongolia, Taiwan, and the Russian Far East (Chinese Academy of Science, Institute of Zoology 1986; Haack et al. 2002; Xu 2003; Yu 1992; Baranchikov et al. 2008). In China, EAB has been reported from Heilongjiang, Jilin, Lianoning, Shandong, and Hebei provinces and Inner Mongolia (Yu 1992; Hou 1993). Liu et al. (2003) conducted exploratory surveys of EAB and its natural enemies in China in Heilongjiang, Jilin, Lianoning, Hebei, and Shandong Provinces and the provincial-level city of Tianjin. They found limited and patchy occurrences of EAB attacking ash trees in all but Shandong Province; in subsequent years, EAB was collected at a site in Beijing (Bauer, unpublished data). Similarly, Wei et al. (2004) conducted field surveys for EAB in China and found limited distribution mainly in areas of Harbin, Mudanjiang, Hejiang, and Yichun in Heilongjiang Province; Changchun, Jilin, Jiaohe, and Dunhua in Jilin Province; Shenyang, Dandong and Benxi in Liaoning Province; Qinhuangdao and Tangshan in Hebei Province; and Tianjin. In South Korea and the Russian Far East, limited EAB damage has been recorded since the 1970s (Wei et al. 2004; Baranchikov et al. 2008).

In North America, EAB has killed tens of millions of ash trees in at least 15 states and in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. Infestations are widespread throughout much of Michigan, Ohio, and Indiana. More recent infestations are known in Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Missouri, Iowa, Kentucky, West Virginia, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, and Tennessee (Cooperative Emerald Ash Borer Project 2010). Larvae of EAB infest all species of North American ash so far encountered, including black ash (F. nigra), blue ash (F. quadrangulata), green ash (F. pennsylvanica), white ash (F. americana), and pumpkin ash (F. profunda) (Bauer, unpublished results). Thus far, EAB’s North American hosts appear limited to trees in the genus Fraxinus (McCullough et al. 2008). EAB larvae damage ash trees by feeding beneath the outer bark, on phloem and outer sapwood (Anulewicz et al. 2008). EAB individuals develop from egg to adult in 1 or 2 years depending on the age of the infestation and ash tree health (Cappaert et al. 2005). Adult emergence usually begins in May or June, with adults creating characteristic D-shaped exit holes in the bark upon emergence. Larval galleries can effectively girdle the trees, resulting in the cessation of water and nutrient flow, causing large ash trees to die within 3–4 years of the initial EAB infestation and saplings to die within a year (Poland and McCullough 2006).

EAB is one of several invasive insect species introduced into North America, including the Argentine ant (Linepithema humile Mayr) (see Tsutsui et al. 2001), the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren, (Ross et al. 2007; Shoemaker et al. 2006), and the gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar (L.), (Reineke et al. 1999; Elkinton and Liebhold 1990). Molecular markers are widely used to study invasive species, with applications ranging from assessing genetic variation (Roderick 1996; Sakai et al. 2001), to reconstructing invasion history (Elderkin et al. 2004), identifying population origin (population assignment tests) and the number of introductions (Grapputo et al. 2005), and developing control strategies (Szalanski and Owens 2003; Conord et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2006; Fu et al. 2010). Understanding the geographic origin, population biology and genetic variation of an invasive species can provide important information on suitable habitat, potential location(s) of effective biological control agents, or predict the effectiveness of a control agent (Allendorf and Lundquist 2003; Sakai et al. 2001; Kambhampati and Rai 1991; Lee 2002; Scheffer and Grissell 2003). Additionally, characterization of population genetic structure within an invasive species provides benchmark data for comparison with similar data from other invasive species. Population assignment tests allow the estimation of the probability that a particular individual originated from each of a number of possible source populations, and have been applied broadly to estimate the origin of invasive species (Bonizzoni et al. 2001; Genton et al. 2005; Tsutsui et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2006), confirm the population structure of native and/or invasive populations (Elderkin et al. 2004; Paupy et al. 2004), and to assess population structure to design eradication strategies (Abdelkrim et al. 2005).

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequencing and DNA fingerprinting using amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLPs) are used both alone and in tandem to characterize the population genetic structure of invasive species and to carry out population assignment tests. For example, Cognato et al. (2005) employed DNA sequences of the widely used mtDNA cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) gene to determine the geographic origin of the red turpentine beetle, Dendroctonus valens LeConte, that was introduced from North America into China. AFLPs provide data from a high number of polymorphic loci throughout the whole genome of an individual without prior genetic knowledge of the organism (Vos et al. 1995). This allows for rapid detection of polymorphisms in a population that is not possible with gene or DNA fragment sequencing (Mueller and Wolfenbarger 1999). AFLPs have been used successfully to determine the genetic structure of invasive zebra mussels, Dreissena polymorpha (Pallas), in their introduced range (Elderkin et al. 2004), and to identify the geographic origins of gypsy moth (Reineke et al. 1999) and the coffee berry borer, Hypothenemus hampei (Ferrari) (Benavides et al. 2005).

Salvato et al. (2002) used AFLP and mtDNA to assess population genetic variation and structure in two sibling species of the winter pine processionary moth (Thaumetopoea pityocampa and Th. wilkinsoni). Strong genetic differentiation between the two species as well as geographic structuring within Th. pityocampa was detected with both markers. AFLP and mtDNA markers were also successfully used to assess phylogeographical patterns of the wooly adelgid, Adelges cooleyi, in western North America (Ahern et al. 2009). Grapputo et al. (2005) used both AFLP and mtDNA markers to determine the geographic origin and population structure of the Colorado potato beetle (CPB), Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say), in its native North American range and introduced range in Europe. CPB populations in Europe had only a portion of the AFLP variability observed in North America, and the authors observed a single mtDNA haplotype in CBP in Europe, suggesting that the introduced European CPB populations went through a genetic bottleneck.

In the present study, we utilized mtDNA and AFLP markers in tandem to characterize genetic variation and population genetic structure of EAB in both its native Asian range and introduced North American range. We also obtained population genetic data for EAB populations using two polymorphic microsatellite loci. The AFLP data were used in population assignment tests to estimate the geographic location of the source EAB population(s) that gave rise to North America’s EAB infestation. We expected to find a reduction of genetic diversity in the introduced North American EAB populations, assuming that the North American EAB were the result of a single introduction. We also tested for isolation by geographic distance in the introduced EAB populations to determine if the introduced insects dispersed via natural movement over time (Taylor et al. 2010, Siegert et al. 2010), or if human-assisted movement of EAB resulted in genetically similar populations existing in widely separated geographic locales.

Methods

Insect collection and population samples

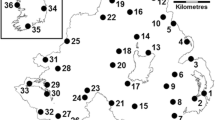

The EAB used in this study were collected in 2003–2008 as larvae and adults from naturally infested ash trees. During that time period, EAB was distributed primarily in a core infestation area in the states of Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, with outlier infestations in other surrounding states. Specimens were collected from introduced populations in Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan, USA, and Ontario, Canada, as well as from native populations in China, Japan, and South Korea (Table 1; Fig. 1). Sampling locations in Asia were selected based on sample availability and on the distribution of known and newly discovered populations (Liu et al. 2003; Wei et al. 2004). A network of collaborators from government agencies and academic institutions was established to assist in insect collections. EAB were field collected as larvae or adults preserved in 70% EtOH, shipped to the Bauer laboratory’s quarantine facility at Michigan State University, where they were transferred to 90% ethanol, and stored at −20°C until analyzed. Some Michigan EAB samples were reared to adulthood from infested ash logs (Bray 2009).

Geographic locations from which emerald ash borer specimens were collected for this study. a Asia. Province or provincial level cities (with collection locations in parentheses) are as follows: CHINA: Tianjin City (1-Dagang, 2- Hangu); Liaoning (3, 4- Shenyang, 5- Benxi); Jilin (6-Changchun City, 7- Jiutai, 8- Jilin City); Hebei (9-Tangshan); Beijing (10-Chaoyang); Heilongjiang (11–Harbin); JAPAN: Miyagi (12- Shirioshi City); SOUTH KOREA: Chungchongnam-do (13- Daejeon); Gyeonggi-do (14- Suwon); Gyeongsangbuk-do (15- Sangju); Gangwon-do (16- Inge, 17- Samcheok); b North America. State or Province (with collection locations in parentheses) are as follows: CANADA: Ontario (1-Windsor); USA: Illinois (2-Peru); Indiana (3-Shipshewana); Michigan (4-Lansing, 5- Moran, 6-Livonia, 7-Plymouth)

EAB were obtained from 17 localities throughout the insect’s native Asian range [China (12), South Korea (4), and Japan (1)], and from 7 localities in North America [Michigan (4 localities: Lansing, Livonia, Moran, and Plymouth), Illinois (1: Peru), Indiana (1: Shipshewana), and Ontario, Canada (1: Windsor)] (Table 1; Fig. 1). For the 17 localities in Asia, 8 distinct geographic populations were defined based on geographic proximity (country or province). These eight populations that were used for the analyses are: (1) South Korea, (2) Japan, (3) Beijing, (4) Tianjin City, (5) Hebei, (6) Liaoning, (7) Jilin, and (8) Heilongjiang. This set of eight populations is referred to as “Asia8”. A subset of these populations (Tianjin City, Hebei, Liaoning, and Jilin) was defined as “Asia4” and was used for some analyses, excluding the remaining four Asian localities due to the small sample sizes (Beijing: n = 2 individuals, Heilongjiang: n = 5, South Korea: n = 7, and Japan: n = 2).

DNA isolation

EAB total genomic DNA was extracted from larval tissue (after removal of the digestive tract to avoid potential contamination from gut contents) or from adult femur muscle tissue using a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN cat. no. 51304) as described by the manufacturer with the following modifications. For larval tissue, two abdominal segments were homogenized in 20 μL protease K and 180 μL QIAGEN ATL buffer. If an adult hind-leg was used, the femur was removed from the thorax and cut in half perpendicularly with a sterile razor blade to expose tissue and then combined with protease K and QIAGEN ATL buffer. Tissue homogenates were incubated overnight at 56°C on a rocking platform. DNA was then eluted, and purified DNA samples were stored at −20°C. Quantification of DNA was carried out using a Nanodrop system (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE).

Mitochondrial DNA gene sequences

A partial sequence (approx. 450 bp) of the COI gene was amplified from EAB individuals using the primers C1-J-1751 (5′-GGA TCA CCT GAT ATA GCA TTC CC- 3′) and C1-N-2191 (5′-CCC GGT AAA ATT AAA ATA TAA ACT TC- 3′) described by Simon et al. (1994). PCR was carried out in a total reaction volume of 25 μL, which contained 9.3 μL ddH20, 2 μL 10X Taq polymerase buffer (Invitrogen), 1.6 μL 50 mM MgCl2 (Invitrogen), 0.4 μL Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen 5 units/μL), 2 μL of 10 mM each deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dATP, dTTP, dCTP, and dGTP), 1.5 μL of 10 μM oligonucleotide forward and reverse primer, and 2.7 μL sample DNA. Reactions were carried out on a PE9700 Thermal Cycler with the following cycling protocol: 5 min at 95°C, 35 cycles of 120 s at 94°C, 90 s at 52°C, and 120 s at 72°C, followed by a final extension for 7 min at 72°C. PCR products were purified using QIAGEN MinElute PCR Purification Kits (cat no. 28004) to remove unincorporated primers and nucleotides. Purified PCR product (5 μL) was combined with 4 μL ddH20 and 3 μL of 10 μM primer for forward and reverse sequencing at the Michigan State University (MSU) Genomics Technology Support Facility. Alignment of obtained sequences was performed using SeqEd Ver 1.0.3 (Applied Biosystems).

Mitochondrial COI haplotype relationships were analyzed by statistical parsimony using the program TCS (vers. 1.21; http://darwin.uvigo.es/software/tcs.html; Clement et al. 2000). This analysis allows for the possibility that the ancestral population is observed in the sample set. Haplotype relationships from TCS were displayed as a network. Haplotype diversity (h) was also determined using the TCS program.

Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP)

The AFLP plant mapping protocol (Applied Biosystems Part #402083) was used to generate fragments for fingerprinting EAB individuals. Pre-selective amplifications were carried out using an MseI complementary primer (MseI adaptor with the recognition site and 3′C) and an EcoRI complementary primer (EcoRI adaptor with recognition site and 3′A). Four primer pair combinations used for selective amplification were run on each EAB sample (Primer Pair I: EcoRI-AGG/MseI-CTT, Primer Pair II: EcoRI-ACT/MseI-CAG, Primer Pair III: EcoRI-ACT/MseI-CTT, Primer Pair IV: EcoRI-AGG/MseI-CAG. Selective amplifications were carried out in a PE9700 thermal cycler with the following program: one cycle of 94°C for 2 min; 10 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 66°C for 30 s, 72°C for 2 min decreasing by one degree at the second step of each cycle; 20 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min; with a final extension step of 60°C for 30 min. Electrophoretic separation of DNA fragments generated by selective amplification was carried out on an Applied Biosystems ABI PRISM® 3100 Genetic Analyzer at the MSU Genomics Technology Support Facility.

Electropherograms were examined using GeneScan 3.1 software (Applied Biosystems) for scoring fragments. Fragments were scored only in the size range for each primer pair in which amplification was consistent across all samples scored. Size range bins were established by manual examination of all electropherograms and fragments (peaks) coded manually as present (1) or absent (0) for each individual locus. Loci were scored as present if peak height was greater than 50 reflectance units.

AFLP allele frequencies, percent polymorphic loci, expected heterozygosities, Nei’s population genetic distance (D), and Fst were estimated using AFLP-SURV (Vekemans et al. 2002). For allele frequency determinations, the Bayesian method of analysis was used with a non-uniform prior distribution of allele frequencies (assuming Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium). The equations of Lynch and Milligan (1994) were used to estimate the proportion of polymorphic loci (PLP) and expected heterozygosities (Hj) for each population. Lower overall values of polymorphism and expected heterozygosities are expected in North American EAB if they are the result of a single or several small introductions from the same geographic source. Fst, was calculated with 500 permutations to determine differentiation among populations at the 1% level (Lynch and Milligan 1994). A high value of overall Fst (Wright 1951; Conner and Hartl 2004) is generally considered to indicate strong differentiation among populations. Neighbor-joining dendrograms showing relationships of EAB pairwise population genetic distances were constructed in Phylip (Felsenstein 2005) using Nei’s D.

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) for AFLP data was carried out using GenAlEx 6.1 (http://www.anu.edu.au/BoZo/GenAlEx/; Peakall and Smouse 2006). This analysis allowed the partitioning of molecular genetic variation among and within populations. GenAlEx also provided an additional estimate of pairwise population genetic differentiation (Φpt) for all Asian and North American EAB populations. Significance of pairwise Φpt values was determined via 999 permutations of each data set. Mantel tests were carried out in GenAlEx to test for isolation-by-distance in both the Asian and North American EAB populations. Geographic distances for pooled samples were taken from the geographic center of the pooled localities.

Population assignment tests were carried out using AFLPOP version 1.1 (http://www2.bio.ulaval.ca/louisbernatchez/downloads.htm; Duchesne and Bernatchez 2002) to estimate from which of several putative EAB source populations in Asia each North American EAB individual was derived. Analyses were carried out using both the four Asia4 populations and the eight Asia8 populations as possible source populations using 100 log likelihood difference to allocate genotypes and 500 artificial genotypes generated to estimate P values for individual log likelihoods. Only individuals with data available from all four AFLP primer pairs were used in the AFLPOP analyses (AFLPOP does not accommodate missing data).

Microsatellite data

Allelic variation was assessed for EAB at two microsatellite loci (C–C5 and C–C8) developed for EAB by Dr. Jennifer Cory and laboratory personnel at Simon Fraser University (unpublished). The primer sequences used for PCR amplification of alleles at locus C-C5 (trinucleotide repeat (ACC)9) were 5′-TCGATGCAACAAAGACCTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGCTTTTAGGTTTTGCTGTG-3′ (reverse), while at locus C–C8 (mixed repeat (ACC)6(AAT)2) the primers were 5′-CGTCGATTAACTTTTAGTTCAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCAGAAGATGCTGTAGTTGAAG-3′ (reverse). PCR conditions were essentially as described for mtDNA amplifications.

Microsatellite allele data were analyzed using the program MSA (Microsatellite Analyzer, vers. 4.05; http://i122server.vu-wien.ac.at/; Dieringer and Schlotterer 2003) to determine allele frequencies and observed and expected heterozygosities. Population structure of EAB within North America and within Asia was estimated from microsatellite data by AMOVA using ARLEQUIN 3.0 (Excoffier et al. 2005). The significance level of Φst in pairwise population comparisons was α = 0.05.

Results

Analysis of mtDNA COI variation

DNA sequencing of a 439 bp fragment of the COI gene was carried out for 94 EAB individuals from the 8 Asian populations and 119 EAB individuals from the 7 North American populations in this study (Table 1). A single common mitochondrial haplotype (H1) was found in all 119 North American EAB individuals, as well as in 84 of the 94 Asian EAB individuals (GenBank Accession #AY864194) (Table 2). Eight other haplotypes (H2–H9) were observed in other Asian EAB populations, with six of these haplotypes (H2–H7) differing from the common haplotype by a single nucleotide base pair change, one haplotype by two base pairs (H8), and the final haplotype (H9), obtained from the EAB individual from Shirioshi City, Japan, differing from the common haplotype by 21 base pair changes (Table 2). A total of 29 nucleotide changes occurred at 25 nucleotide sites along the 439 bp sequence. Substitutions at third codon positions accounted for all of the differences between the haplotypes except for a single first codon position change at nucleotide position 305 (in GenBank Accession #AY864194). All nucleotide changes were synonymous and thus had no impact on the inferred amino acid sequence of the COI protein.

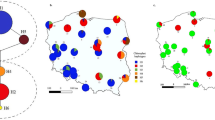

Statistical parsimony analysis of the EAB mtDNA sequence data yielded two groups in the resulting network (Fig. 2). The haplotype (H9) from the single individual from Shirioshi City, Japan differed from the common haplotype by 4.8% and separated into its own group in the analysis. The remaining haplotypes formed the second group. All EAB specimens from North America and the majority from China had the common haplotype, H1. Three other haplotypes were observed in China; two haplotypes from single individuals in Benxi (Liaoning), H2 and H3, and a third haplotype from two individuals in Shenyang (Liaoning), H4. The common haplotype, H1, was observed in South Korea along with five other haplotypes, H4-H8. Haplotypes H4, H5, and H8 were each observed in single individuals from Daejeon, while H6 and H7 were each observed in single individuals from Inge.

Haplotype network for EAB individuals collected in Asia and North America based on partial sequences (439 bp) of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I gene (COI). Circles are drawn roughly proportional to the frequency of occurrence of each of the nine COI mtDNA haplotypes from EAB, and are color coded by geographic origin of EAB individuals carrying that haplotype (Red—China; Blue—South Korea; Orange—Japan; White—North America). The common haplotype (H1) was observed in 84 of the 94 Asian EAB in the sample, with each of the other haplotypes observed once, except for H4, which was observed three times. All North American EAB in the sample (n = 119) had the common haplotype. Numbers on the lines between haplotypes represent positions of nucleotide substitutions between a given haplotype and the common haplotype (H1; GenBank AY864194). The Japanese haplotype, H9, differed from H1 by 21 nucleotide substitutions

Analysis of AFLP variation

AFLP profiles were obtained from 90 EAB individuals from 8 defined populations in Asia, and 126 individuals from 7 defined populations in North America (Table 1). Using 4 selective primer pair combinations, data were obtained from 108 polymorphic AFLP loci. Overall, AFLP polymorphism was higher in Asia than in North America; Asian EAB had 86.1% polymorphic loci (PLP) while North American EAB had 63.9% PLP (Table 3). Within Asia, PLP ranged from 65.7% in Beijing (n = 2) and South Korea (n = 6), to a high of 88.9% in Tianjin City (n = 17). Within North America, PLP ranged from 71.3% in Indiana to 90.7% in Illinois. A similar trend was observed in expected heterozygosity (Hj) (Table 3). Within Asia, Hj ranged from a low of 0.229 in South Korea to a high of 0.369 in Japan, with an overall Hj in Asia of 0.268. On the other hand, in North America, Hj ranged from 0.174 in Livonia, MI to 0.281 in Ontario, with an overall Hj of 0.228.

Conversely, population genetic differentiation, as judged by FST and ΦPT, appeared to be higher in North America than in Asia (Table 4). While FST for the Asia8 populations was 0.150, this dropped to 0.018 when only the Asia4 populations were included in the analysis. On the other hand, in North America, the seven defined populations had an overall FST of 0.094. Estimation of ΦPT yielded similar results (Table 4), with overall ΦPT = 0.071 for Asia8, which dropped to 0.031 in the Asia4 sample. In North America, however, overall ΦPT was 0.119.

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was used to partition AFLP variation within and among EAB populations from both the native (Asia) and introduced (North America) ranges (Table 5). In Asia (considering all eight populations; Asia8), 7% of the total variation was among populations, while 93% of the total variation was within populations. When only the Asia4 populations were considered, among population variation fell to 3%, while within population variation rose to 97%. On the other hand, in North America (7 populations), 12% of the total variation was among populations, while 88% of the total variation was within populations.

Analysis of pairwise population differentiation was carried out using AFLP data by estimation of ΦPT values between all pairs of populations in Asia and North America (Table 6). Consistent with the overall ΦPT values obtained, all pairwise comparisons between North American EAB populations (overall ΦPT = 0.119) were significant. On the other hand, several pairwise comparisons between Asian populations (overall ΦPT = 0.071 for Asia8) were not significant, and two ΦPT values (Tianjin-Liaoning; Jilin-Liaoning) were not significant amongst the Asia4 populations (overall ΦPT = 0.031) that were included in the analysis.

Analysis of pairwise population differentiation was also carried out by neighbor-joining (NJ) analysis of pairwise genetic distances (Nei’s D) between all Asian and North American populations (Fig. 3). The North American EAB populations formed a cohesive derived cluster within the NJ tree [with the exception of the inclusion of Beijing (n = 2)], with the Illinois and Canada populations appearing as basal taxa in the North American group. Among the Asian populations, the Hebei population appeared as the most derived taxon and thus appeared as sister to the North American EAB populations.

Population assignment tests were performed to determine the most likely geographic origin of North American individuals using both the Asia8 and the Asia4 populations as putative sources. Overall, 88% of the North American EAB individuals (91/103) were assigned to either Hebei province (55 individuals) or Tianjin City province (36 individuals) (Table 7). None of the North American individuals were assigned to Beijing or Heilongjiang province, South Korea or Japan. Identical results were obtained in the population assignment tests regardless of whether the analysis was done using the Asia8 populations or only the Asia4 populations as putative source populations.

Analysis of microsatellite variation

Allele frequency data were obtained at two polymorphic microsatellite loci for individuals from four Chinese EAB populations (Asia4) and the seven North American EAB populations (Table 8). Four alleles were observed at locus C5 (141, 144, 150, 153) in the Asia4 sample, while only three of these alleles were present in the North American EAB (allele 141 was absent). Similarly, at locus C8, three alleles were present in the Chinese populations (225, 231, 234) while only alleles 225 and 231 were observed in North American EAB individuals. When two individuals from South Korea were genotyped, a fifth allele at locus C5 (147) and a fourth allele at locus C4 (228) were observed (data not shown). Although not statistically significant (α = 0.05 level), observed heterozygosities were less than expected at loci C5 and C8 in both the Asia4 and the North American EAB samples (Table 8).

Differentiation between all pairs of populations was tested based on estimates of FST. No significant differences were observed in all pairwise population comparisons based on the microsatellite data. However, when the seven North American populations were pooled and considered as a single metapopulation, significant FST values were observed between North American EAB and Hebei (FST = 0.0412), Liaoning (FST = 0.0639) and Jilin (FST = 0.2390), while the Tianjin City population was not significantly differentiated (FST = 0.0084) from the North American EAB metapopulation.

Discussion

The North American EAB populations examined in this study were most likely the result of a single introduction of EAB from China, probably the region of Hebei province and Tianjin City. If there were multiple introductions, the EAB likely came from the same or highly similar source populations. All three genetic marker types showed a decrease in genetic diversity in the North American EAB metapopulation, as would be expected given a population derived from a portion of a larger source population. In addition, our data indicate the North American EAB populations are more highly structured genetically than the Asian source EAB populations. This may reflect the fact that our dataset captured the early stages of the North American EAB infestation and its subsequent human-assisted spread over relatively long distances in North America.

Genetic structure of EAB populations in Asia and North America

Low genetic diversity in North American EAB

All three genetic marker types employed in this study (mtDNA sequences, AFLP fingerprints, and microsatellites), showed decreased genetic diversity in the North American EAB populations compared to the Asian EAB populations. For example, none of the mitochondrial DNA diversity observed in Asia was detected in the introduced North American EAB populations. All North American EAB individuals surveyed from the seven North American populations (n = 119) carried the same mtDNA haplotype (H1), while eight haplotypes, in addition to H1, were found in Asian EAB populations (Fig. 2). Further, a survey of an additional 111 EAB individuals from North American populations in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Maryland indicated that they also all carried haplotype H1 (Bray 2009).

A reduction in genetic diversity in the North American EAB populations compared to the Asian EAB populations was also indicated by the AFLP data. Based on the AFLP data, the North American EAB populations had significantly lower expected heterozygosity (Hj) than the Asia8 populations (Table 3; t-test: t = 2.51, 13 df, P = 0.026). A similar result was obtained when the North American EAB populations were compared with the Asia4 populations, although the difference was significant only at the α = 0.1 level (t-test: t = 2.1, 9 df, P = 0.065). We also observed a lower percentage of polymorphic AFLP loci (63.9 vs. 85.2%; Table 3) in the North American EAB populations compared with the Asia4 populations, but this difference was not statistically significant (t-test: t = 1, 9 df, P = 0.34).

Finally, analysis of genetic variation in Asian and North American EAB populations revealed reduced genetic diversity in the North American EAB populations. We detected unique alleles in Asian EAB populations at both loci examined (C5 and C8). Allele 141 was present in all of the Asia4 populations at frequencies ranging from 0.050 (Tianjin City) to 0.231 (Liaoning), while this allele was not observed in any of the North American EAB individuals assayed (n = 131). In addition, one of the two individuals examined from South Korea carried allele 147, which was not observed in any other individuals in the sample (Asia or North America). A similar situation was observed at locus C8. Allele 234 was found in two Asian populations (Jilin, 0.031; Liaoning, 0.091), yet this allele was not observed in North America. Also, a unique allele (allele 228) was observed in one of the two individuals examined from South Korea.

High population differentiation in North American EAB

On the other hand, population differentiation, as estimated by ΦPT and Fst, and AMOVA, appears to be more pronounced in the North American EAB populations than in the Asian EAB populations (except on the basis of the mtDNA data, where no structure whatsoever is observed in the North American EAB populations). On the basis of ΦPT analysis of AFLP data (Table 4), the seven North American populations (overall ΦPT = 0.119) are more highly structured than either the Asia4 (overall ΦPT = 0.031) or Asia8 populations (overall ΦPT = 0.071). On the other hand, analyses based on Fst show that, while the North American populations (overall Fst = 0.0940) are more highly structured than Asia4 (overall Fst = 0.0176), the Asia8 populations (overall Fst = 0.1502) are more structured than those in North America. The reason for the discrepancy between the ΦPT and Fst analyses is not clear, although the F-based statistics for the North American populations must be interpreted with caution, as these recently arrived populations violate the assumption of mutation/drift equilibrium.

AMOVA based on AFLP data also supports the hypothesis that there is more population differentiation in North American than Asian EAB populations. In the North American EAB populations, 12% of the molecular variation occurs among populations, with 88% of the molecular variation occurring within populations. This contrasts with 7% of the molecular variation occurring among the Asia8 populations (93% within), and only 3% among the Asia4 populations (97% within).

This higher degree of population differentiation in the North American compared to the Asian EAB populations could be the result of the mode of spread of the genetically less diverse introduced EAB population within North America. If new peripheral populations result from sampling the original invading population, and if different subsets of the standing genetic variation are used as the sources of these new peripheral isolates, we would expect to see a pattern with less genetic diversity that becomes more highly structured. If the primary mode of spread in North America has been human-mediated transport of infested host material over long distances, the new founding populations would have no opportunities for contact (and hence gene flow) between themselves and the original source population or the other peripheral isolate populations.

One possible weakness of our analysis is that the lack of availability of Asian specimens led us in some cases to pool individuals across sites (Table 1). Thus, the Asia4 “populations” used in the analyses actually represent groupings of “collection sites”, which may themselves represent independent populations. This potentially could have led to high within-population variation, and therefore lower between-population variation, in Asia, potentially resulting in a misleadingly low estimate of population differentiation.

While this is a valid concern, some of our data indicate that this may not be a problem in our present analyses. The observed variances in the expected heterozygosity values are of similar magnitude in the Asia4 populations (after pooling) compared to the North American populations (Table 3). In addition, the proportion of that variance that is attributable to sampling individuals (as opposed to loci) is similar across the populations (Table 3). This suggests that pooling individuals across sites has not led to increases in within population variation, and thus an artificially low estimate of overall population differentiation in Asia. Nonetheless, our results should be interpreted with caution.

Where did the North American EAB come from?

Did North American EAB come from China?

One of our major objectives in carrying out this study was to estimate the geographic origin(s) of the North American EAB populations. Our best estimate, given the complete set of analyses of the mtDNA, AFLP and microsatellite data, is that the North American EAB infestation originated in the Tianjin City/Hebei region of China. Several lines of reasoning support this conclusion.

First, none of the mtDNA diversity observed in China and South Korea (haplotypes H2-H8) is represented in North American EAB. In Liaoning province, 27% of the individuals (4/15) carried uncommon mtDNA haplotypes, while in South Korea, 45% of the individuals (5/11) carried uncommon haplotypes. The fact that we did not observe these uncommon haplotypes in the North American EAB does not necessarily mean that the North American EAB were not derived from Liaoning or South Korea. However, it appears more likely that North American EAB originated from areas where these rarer mtDNA haplotypes were not detected.

Second, in pairwise population comparisons based on AFLP data, populations of EAB from Beijing, Hebei, and Tianjin City were less differentiated genetically from the North American EAB (treated as a single population of 126 individuals) than were the populations in Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang and South Korea (data not shown). The microsatellite allele frequency data corroborate the AFLP data; the unique alleles found in the South Korean populations (C5, allele 147; C8, allele 228) were not found in any of the North American EAB examined, nor was the rare allele (C8; allele 234) found in the Jilin and Liaoning populations (Table 8).

Third, population-derivation estimates support the hypothesis that North American EAB originated in the Tianjin City/Hebei region of China. The vast majority of the North American individuals (88%) were assigned to either the Tianjin City or Hebei population, with only 12% of the individuals hypothesized as being derived from Liaoning or Jilin, and none from Beijing, Heilongjiang, South Korea or Japan.

Despite these three lines of reasoning, our data do not allow us to draw definitive conclusions about the origins of the North American EAB populations. While China, notably the region of Hebei province and Tianjian City, is the presumed source of the North American EAB infestation, it is possible that the beetles originated elsewhere in China or in some other Asian country within its native range. Due to small sample sizes from some field sites, some of our results do not have strong statistical support. As mentioned above, one of the major impediments encountered in carrying out this study was difficulty obtaining EAB specimens from Asian localities, which prevented us from establishing a well-sampled, representative set of putative source populations.

Were there multiple introductions?

Another objective of our study was to determine whether the current EAB infestation in North America is the result of a single introduction, or more than one introduction. EAB was first detected in North America in 2002, and was initially found in southeastern Michigan and adjacent Canada near Windsor, Ontario (Haack et al. 2002). Based on dendrochronological reconstruction, Siegert et al. (2007) postulated that EAB was introduced in the early to mid-1990s into Wayne County (Detroit), MI. Since its initial collection in 2002, EAB has been discovered over a wide area including 15 US states (Illinois, Iowa, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin) and 2 Canadian provinces (Ontario and Quebec) as of July 2010 (Cooperative Emerald Ash Borer Project 2010).

Some of our preliminary analyses (Bray et al. 2008) indicated that EAB found in Windsor, Ontario might represent an introduction that was separate from the original EAB introduction in neighboring Michigan. However, based on more detailed analyses of our results, none of the genetic markers used distinguished the Ontario EAB population as genetically distinct from the US EAB populations. The COI sequences of 25 individual EAB from Ontario each carried the common haplotype (H1; Fig. 2), as did all of the other North American EAB individuals examined. Population derivation estimates (Table 7) and analyses of pairwise population genetic distances based on the AFLP fingerprints (Table 6; Fig. 3) did not distinguish the Ontario population from the other North American EAB populations. Likewise, the microsatellite allele frequencies of the Ontario EAB population (Table 8) were not different from those obtained from the other North American EAB populations. Based on these findings, we invoke the most parsimonious explanation of a single EAB introduction from Asia into North America.

Conclusions and future research

Asian EAB

The main conclusions drawn from this study are based on the analysis of a set of Asian EAB populations from northeastern China, South Korea and Japan. Unfortunately, sufficient numbers of EAB individuals were not available from Beijing, Heilongjiang, South Korea and Japan to allow for more robust estimation of population genetic parameters for these populations. In addition, EAB is known to be present in the Russian Far East, the Korean Peninsula, Mongolia, and China’s Inner Mongolia and Shandong provinces (Hou 1993; Chinese Academy of Science, Institute of Zoology 1986). It would be useful to incorporate samples from these other areas of Asia and provinces of China into future studies.

Jendek (1994) synonymized several Agrilus “species/subspecies” under the single name A. planipennis based on consideration of morphological characters. The results of our present study suggest that Jendek should not have synonymized the Japanese A. marcopoli ulmi with EAB. The mtDNA haplotype from the single adult EAB collected in Japan, caught from ash foliage by a local collector (P. Schaefer, personal communication), differed from all the other EAB by 4.8%. Confirmation of host tree is necessary when collecting Agrilus spp. in Asia (Akiyama and Ohmomo 1997). It will be of interest to use molecular markers in combination with morphology to characterize additional EAB individuals from Japan.

Biocontrol

When EAB was discovered in Michigan in 2002, virtually no literature was available on its distribution, host range, and population dynamics in Asia. This study was initiated, in part, to obtain information on the range of EAB in Asia for the purpose of developing a biological control program in the US for management of EAB (Bauer et al. 2004, 2005). Surveys for EAB natural enemies by researchers involved in foreign exploration in northeastern Asia provided many of the specimens used in this study, confirming EAB as the host of several EAB parasitoids. During the course of this work, three EAB parasitoid species native to China were found (Bauer et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2005; Liu et al. 2003, 2007), and release of these Chinese parasitoid species as EAB biocontrol agents started in Michigan in 2007 (Federal Register 2007), and expanded to Ohio and Indiana in 2008, and Maryland and Illinois in 2009 (Bauer et al. in press). As EAB continues to expand its introduced North American range, foreign exploration continues in order to provide additional information on the native range of EAB to identify potential sources of different species and populations of EAB natural enemies.

This study genetically characterizes the invasion of the non-native insect pest, EAB, into North America. The human-assisted spread of EAB appears to have resulted in fragmented populations with high genetic structure since its introduction about 20 years ago. Given this population genetics framework, it should be possible to characterize the stages of the invasion as EAB continues its spread unaided by humans and its likely eventual population crash with the decline of North American ash populations.

References

Abdelkrim J, Pascal M, Calmet C, Samadi S (2005) Importance of assessing population genetic structure before eradication of invasive species: examples from insular Norway rat populations. Conserv Biol 19:1509–1518

Ahern RG, Hawthorne DJ, Raupp MJ (2009) Phylogeography of a specialist insect, Adelges cooleyi: historical and contemporary processes shape the distribution of population genetic variation. Molec Ecol 18:343–356

Akiyama K, Ohmomo S (1997) A checklist of the Japanese Buprestidae. Gekkan-Mushi (1) pp 1–67

Allendorf FW, Lundquist LL (2003) Introduction: population biology, evolution, and control of Invasive species. Conserv Biol 17:24–30

Anulewicz AC, McCullough DG, Cappaert DL, Poland TM (2008) Host range of the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire) (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) in North America: results of multiple-choice field experiments. Environ Entomol 37:230–241

Baranchikov Y, Mozolevskaya E, Yurchenko G, Kenis M (2008) Occurrence of the emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis in Russia and its potential impact on European forestry. EPPO Bull 38:233–238

Bauer LS, Liu H, Haack RA, Petrice TR, Miller DL (2004) Natural enemies of emerald ash borer in southeastern Michingan. In: Proceedings of the 2003 Emerald Ash Borer Research and Technology Development Meeting, September 30—October 01, 2003, Port Huron, Michigan. USDA Forest Service, FHTET Publ, 2004–2002. p 33

Bauer LS, Liu H-P, Haack RA, Gao R, Zhao T, Miller DL, Petrice TR (2005) Emerald ash borer natural enemy surveys in Michigan and China. In: Mastro V, Reardon R (Compilers), Proceedings of Emerald Ash Borer Research and Technology Development Meeting, Romulus, MI USDA FS FHTET-2004-15, pp 71–72 http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/9610

Bauer LS, Liu H-P, Miller DL, Gould JR (2008) Developing a classical biological control program for Agrilus planipennis (Coleoptera: Buprestidae), an invasive ash pest in North America. Newsletter Mich Entomol Soc 53:38–39 http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/1439

Bauer LS, Gould J, Duan J (In press) Emerald ash borer biological control. In: Proceedings, 20th US Department of Agriculture interagency research forum on gypsy moth and other invasive species. USDA FS NRS, Gen Tech Rep

Benavides P, Vega FE, Romero-Severson J, Bustillo AE, Stuart JJ (2005) Biodiversity and biogeography of an important inbred pest of coffee, coffee berry borer (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). Ann Entomol Soc Am 98:359–366

Bonizzoni M, Zheng L, Guglielmino CR, Haymer DS, Gasperi G, Gomulski LM, Malacrida AR (2001) Microsatellite analysis of medfly bioinfestations in California. Molec Ecol 10:2515–2524

Bray AM (2009) AFLP, mtDNA, and microsatellite analysis of emerald ash borer population structure from Asia and North America. Dissertation, Michigan State University

Bray AM, Bauer LS, Haack RA, Poland T, Smith JJ (2008) Emerald ash borer genetics: an update. In: Proceedings of the 2007 Emerald Ash Borer Research and Technology Development Meeting, October 23–24, 2007, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. USDA Forest Service, FHTET Publ. 2008–2007: p 11

Cappaert D, McCullough DG, Poland TM, Siegert NW (2005) Emerald ash borer in North America: a research and regulatory challenge. Am Entomol 51:152–165

Chinese Academy of Science, Institute of Zoology (1986) Agrilus marcopoli Obenberger. In: Editorial committee (eds.) Agriculture Insects of China (part I). China Agriculture Press, Beijing, China, p 445

Clement M, Posada D, Crandall K (2000) TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Molec Ecol 9:1657–1660

Cognato AI, Sun J-H, Anducho-Reyes MA, Owen DR (2005) Genetic variation and origin of red turpentine beetle (Dendroctonus valens LeConte) introduced to the People’s Republic of China. Agric For Entomol 7:87–94

Conner JK, Hartl DL (2004) A primer of ecological genetics. Sinauer Associates, Inc. Sutherland, Massachusetts

Conord C, Lemperiere G, Taberlet P, Despres L (2006) Genetic structure of the forest pest Hylobius abietis on conifer plantations at different spatial scales in Europe. Heredity 97:46–55

Cooperative Emerald Ash Borer Project (2010) http://www.emeraldashborer.info/; Accessed June 2010

Dieringer D, Schlotterer C (2003) Microsatellite Analyser (MSA): a platform independent analysis tool for large microsatellite data sets. Molec Ecol Notes 3:167–169

Duchesne P, Bernatchez L (2002) AFLPOP: a computer program for simulated and real population allocation based on AFLP data. Molec Ecol Notes 2:380–383

Elderkin CL, Perkins EJ, Leberg PL, Klerks PL, Lance RF (2004) Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis of the genetic structure of the zebra mussel, Dreissena polymorpha, in the Mississippi River. Freshw Biol 49:1487–1494

Elkinton JS, Liebhold AM (1990) Population dynamics of Gypsy moth in North America. Ann Rev Entomol 35:571–596

Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S (2005) Arlequin, Version 3.0: An integrated software package for population genetic data analysis. Evol Bioinforma Online 1:47–50

Federal Register (2007) The proposed release of three parasitoids for the biological control of the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) in the continental United States: environmental assessment. Federal Register 72:28947–28948, Docket No. APHIS-2007-0060 http://www.regulations.gov/fdmspublic/component/main?main=DocketDetail&d=APHIS-2007-0060

Felsenstein J (2005) PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package) version 3.6. Distributed by the author. Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle

Fu D-Y, Hu S-J, Ye H, Haack RA, Zhou P-Y (2010) Pine wilt disease in Yunnan, China: evidence of non-local pine sawyer Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) populations revealed by mitochondrial DNA. Insect Science 17:439–447

Genton BJ, Shykoff JA, Giraud T (2005) High genetic diversity in French invasive populations of common ragweed, Ambrosia artemisiifolia, as a result of multiple sources of introduction. Molec Ecol 14:4275–4285

Grapputo A, Boman S, Lindstrom L, Lyytinen A, Mappes J (2005) The voyage of an invasive species across continents: genetic diversity of North American and European Colorado potato beetle populations. Molec Ecol 14:4207–4219

Haack RA, Jendek E, Liu H, Marchant K, Petrice T, Poland T, Ye H (2002) The emerald ash borer: a new exotic pest in North America. Newsletter Mich Entomol Soc 47(3–4):1–5

Hou T-Q (1993) Agrilus marcopoli Obenberger. In: Editorial committee (eds.) Fauna of Shandong Forest Insect. China Forestry publishing House. Beijing, China. p 237, (in Chinese)

Jendek E (1994) Studies in the East Palaearctic species of the genus Agrilus Dahl, 1823 (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) Part I. Entomol Problems 25:9–25

Kambhampati S, Rai KS (1991) Mitochondrial DNA variation within and among populations of the mosquito Aedes albopictus. Genome 34:288–292

Kim KS, Cano-Rios P, Sappington TW (2006) Using genetic markers and population assignment techniques to infer origin of boll weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) unexpectedly captured near an eradication zone in Mexico. Environ Entomol 35:813–826

Lee CE (2002) Evolutionary genetics of invasive species. Trends Ecol Evol 17:386–391

Liu H, Bauer LS, Gap R, Zhao T, Petrice TR, Haack RA (2003) Exploratory survey for the emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) and its natural enemies in China. Grt Lakes Entomol 36:191–204

Liu H-P, Bauer LS, Miller DL, Zhao TH, Gao R-T, Song L, Luan Q, Jin R, Gao C (2007) Seasonal abundance of Agrilus planipennis (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) and its natural enemies Oobius agrili (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) and Tetrastichus planipennisi (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) in China. Biol Control 42:61–71

Lynch M, Milligan BG (1994) Analysis of population genetic structure with RAPD markers. Molec Ecol 3:91–99

McCullough DG, Schneeberger NF, Katovich SA (2008) Pest alert: emerald ash borer. USDA Foret Service, Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry, NA-PR-02-04. http://www.na.fs.fed.us/spfo/pubs/pest_al/eab/eab.pdf. Accessed Feb 2010

Mueller UG, Wolfenbarger LL (1999) AFLP genotyping and fingerprinting. Trends Ecol Evol 14:389–394

Paupy C, Orsoni A, Mousson L, Huber K (2004) Comparisons of amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), microsatellite, and isoenzyme markers: population genetics of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) from Phnom Penh (Cambodia). J Med Entomol 41:664–671

Peakall R, Smouse PE (2006) GenAlEx 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Molec Ecol Notes 6:288–295

Poland TM, McCullough DG (2006) Emerald ash borer: invasion of the urban forest and the threat to North America’s ash resource. J Forestry April-May:118–124

Reineke A, Karlovsky P, Zebitz CPW (1999) Amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis of different grographic populations of the gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae). Bull Entomol Research 89:79–88

Roderick GK (1996) Geographic structure of insect populations: gene flow, phylogeography, and their uses. Ann Rev Entomol 41:325–352

Ross KG, Krieger JB, Keller L, Shoemaker DD (2007) Genetic variation and structure in native populations of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta: evolutionary and demographic implications. Biol J Linn Soc 92:541–560

Sakai AK, Allendorf FW, Holt JS, Lodge DM, Molofsky J, With KA, Baughman S, Cabin RJ, Cohen JE, Ellstrand NC, McCauley DE, O’Neil P, Parker IM, Thompson JN, Weller SG (2001) The population biology of invasive species. Ann Rev Ecol Syst 32:305–322

Salvato P, Battisti A, Concato S, Masutti L, Patarnello T, Zane L (2002) Genetic differentiation in the winter pine processionary moth (Thaumetopoea pityocampa - wilkinsoni complex), inferred by AFLP and mitochondrial DNA markers. Molec Ecol 11:2435–2444

Scheffer SJ, Grissell EE (2003) Tracing the geographical origin of Megastigmus transvaalensis (Hymenoptera: Torymidae): an African wasp feeding on a South American plant in North America. Molec Ecol 12:415–421

Shoemaker DD, Ahrens ME, Ross KG (2006) Molecular phylogeny of fire ants of the Solenopsis saevissima species-group based on mtDNA sequences. Molec Phylogenetics Evol 38:200–215

Siegert NW, McCullough DG, Liebhold AM, Telewski FW (2007) Dendochronological reconstruction of the establishment and spread of emerald ash borer. In: Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team: Emerald ash borer research and technology development meeting

Siegert NW, McCullough DG, Williams DW, Fraser I, Poland TM, Pierce SJ (2010) Dispersal of Agrilus planipennis (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) from discrete epicenters in two outlier sites. Environ Entomol 39:253–265

Simon C, Frati F, Beckenbach A, Crespi B, Liu H, Flook P (1994) Evolution, weighting, and phylogenetic utility of mitochondrial gene sequences and a compilation of conserved polymerase chain reaction primers. Ann Entomol Soc Am 87:651–701

Szalanski AL, Owens CB (2003) Genetic variation of the southern corn rootworm, (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Fla Entomol 86:329–333

Taylor RAJ, Bauer LS, Poland TM, Windell K (2010) Flight performance of Agrilus planipennis (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) on a flight mill and in free flight. J Insect Behavior 23:128–148

Tsutsui ND, Suarez AV, Holway DA, Case TJ (2001) Relationships among native and introduced populations of the Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) and the source of introduced populations. Molec Ecol 10:2151–2161

USDA-APHIS (2010) Emerald ash borer quarantine map. http://www.aphis.usda.gov/plant_health/plant_pest_info/emerald_ash_b/downloads/multistateeab.pdf. Accessed Feb 2010

Vekemans X, Beauwens T, Lemaire M, Roldan-Ruiz I (2002) Data from amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers show indication of size homoplasy and of a relationship between degree of homoplasy and fragment size. Molec Ecol 11:139–151

Vos P, Bleeker M, Reijans M, VanDelee T, Hornes M, Frijters A, Pot J, Peleman J, Kuiper M, Zabeau M (1995) AFLP-A new technique for DNA-Fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res 23:4407–4414

Wei X, Reardon D, Wu Y, Sun JH (2004) Emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire (Coleoptera; Buprestidae), in China: a review and distribution survey. Acta Entomol Sinica 47:679–685

Wright S (1951) The genetic structure of populations. Ann Eugen 15:323–354

Xu G-T (2003) Agrilus marcopoli Obenberger. Atlas of ornamental pests and Diseases. China Agriculture Press, Beijing, pp 321–322

Yu C (1992) Agrilus marcopoli Obenberger. Pages 400–401 in G. Xiao [ed.], Forest Insects of China, 2nd edn. China Forestry Publishing House, Beijing, China

Zhang Y, Huang D, Zhao T, Liu H, Bauer LS (2005) Two new species of egg parasitoids (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) of wood-boring beetle pests from China. Phytoparasitica 33:253–260

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the network of collaborators who helped us obtain the insects used in this study, including countless members in North America from USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station, Michigan State University, Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan Departments of Agriculture, and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. We would like to specifically thank collaborators in Asia and the US who made sampling possible, in China: Dr. Houping Liu (Michigan State University, Dr. Tonghai Zhao and Dr. Ruitong Gao (Chinese Academy of Forestry), and Mr. Roger Fuester (USDA ARS BIIR); in South Korea: Dr. David Williams (USDA APHIS CPHST), Dr. Choo Ho Yul (Gyeongsang National University) and Dr. Lee DongWoon (Kyungpook National University); in Japan—Dr. Paul Schaefer (USDA-ARS-BIIR), Dr. Naoto Kamata (University of Tokyo), Mr. Minemitsu Kaneko (Japan Wildlife Research Center), and Mr. Takaharu Hattori. We also thank Deborah Miller (USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station, E. Lansing, MI) for organizing and managing the long-term storage of EAB collections from China and North America; Dr. Jennifer Cory (Simon Fraser University) for designing and developing the microsatellite primers used in the study, Dr. Deb McCullough (Michigan State University) for supporting the early microsatellite development work, Dr. Rob Ahern for his help with AFLP data analysis and interpretation, Mike Grillo for his work during the earliest phases of the EAB project, Dr. Rodrigo Mercador and Dr. Yigen Chen for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript, and Marlene Cameron for assistance with the preparation of Figure 1. Research funding for the project was provided by the USDA Forest Service (03-JV-11231300096), Michigan State University (MSU) Project GREEEN (Generating Research and Extension to meet Economic and Environmental Needs), the MSU Office for International Studies and Programs, the MSU Department of Entomology, and the MSU Graduate School.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bray, A.M., Bauer, L.S., Poland, T.M. et al. Genetic analysis of emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire) populations in Asia and North America. Biol Invasions 13, 2869–2887 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-011-9970-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-011-9970-5