Abstract

Iguana iguana is native to Central and South America, and was introduced into Puerto Rico in the 1970s as a result of pet trade. The invasive biology of this reptile has not been studied in Puerto Rico, where its negative effects may threaten local biodiversity. The purposes of this study were to: (1) estimate population densities of I. iguana; (2) describe some aspects of its reproductive biology; and (3) assess its potential impacts. Visual-encounter surveys were performed at Parque Lineal in San Juan and Canal Blasina in Carolina, while nesting activity data were collected at Las Cabezas de San Juan in Fajardo. Densities of I. iguana in Puerto Rico reached a maximum of 223 individuals ha−1, higher than in any known locality in its native range, and showed fluctuations related to seasonality. Our 2008–2009 observations at the nesting sites document that this population of I. iguana is a reproductively successful species, producing more than 100 egg clutches and 2,558 eggs with a 91.4% egg viability. The ability to proliferate in a low predation environment and the absence of good competitors are the major drivers of the population densities observed in Puerto Rico. We found evidence that I. iguana is threatening native biodiversity and impacting infrastructure, agriculture and human safety. Thus, a management program to control the species must soon be developed to prevent this invasive reptile from becoming more widespread and dominant in other localities around the island.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While the effects of invasive mammals are widely documented, invasive reptiles have just begun to receive attention (Bomford et al. 2009; Rodda et al. 2009). Human mediated introductions of reptiles have caused the extinction of native fauna (Savidge 1987), hybridization with native species (Day and Thorpe 1996), and increased the incidence of salmonellosis in humans (Mermin et al. 1997).

The green iguana (I. iguana) is native to Central and South America, and was introduced to Puerto Rico in the 1970s by the pet trade (Rivero 1998). Since its introduction, this species has become established and widespread around the main island, smaller islands and keys (Thomas and Joglar 1996). In several localities of eastern and northeastern Puerto Rico, this species has become abundant (Joglar 2005), possibly due to increased habitat availability and the absence of natural predators. Iguana iguana adults are mostly herbivorous, but occasional predation on bird eggs, chicks, invertebrates, small mammals and carrion have been reported (Loftin and Tyson 1965; Schwartz and Henderson 1991; Rivero 1998; Savage 2002; Townsend et al. 2003, 2005; Krysko et al. 2007). Life history and demographic studies of I. iguana have not been conducted in Puerto Rico. Considering the negative characteristics of an invader, I. iguana has the potential to cause negative effects on native flora, fauna and agriculture. Thus, studies are critical to determine the ecological impacts of I. iguana, and to provide scientifically based management recommendations.

In this paper, we show the results of continuous monitoring of I. iguana populations at three localities in mangrove swamps in Puerto Rico in an effort to: (1) estimate population densities at different sites; (2) describe some aspects of its reproductive biology; and (3) evaluate potential impacts (ecosystems, biodiversity, etc.). These data are critical to determine if a management program to control I. iguana populations is needed and, if so, to suggest an effective management strategy.

Materials and methods

Study sites

Iguana iguana populations were monitored at two localities in Puerto Rico (Fig. 1a): Parque Lineal Enrique Martí Coll, San Juan (18°26′N, 66°04′W), and Canal Blasina, Carolina (18°25′N, 65°58′W). Both study sites are part of the San Juan Bay Estuary, a complex estuarine environment consisting of a series of interconnected channels dominated by mangroves in the subtropical moist forest ecological life zone (Ewel and Whitmore 1973). Parque Lineal is characterized by the abundance of Rhizophora mangle and Laguncularia racemosa, while Canal Blasina is characterized by the abundance of Avicennia germinans and R. mangle. Nesting activity was monitored at Las Cabezas de San Juan Nature Reserve (Fig. 1b), Fajardo (18°22°N, 65°37°W). This site is located in a mixed secondary forest within the subtropical dry forest ecological life zone (Ewel and Whitmore 1973).

Climatic variability at Parque Lineal and Canal Blasina

Climate in Puerto Rico is characterized by two seasons: the cool-dry season, with lower temperatures and precipitation (Range: 29.3–20.8°C, 170.4–77.2 mm); and the warm-wet season, with higher temperatures and precipitation (Range: 31.2–23.1°C, 178.1–93.2 mm) (Colón 1983; SERCC 2010). Since the beginning and end of these seasons may vary from year to year, we analyzed the climate data by averaging mean monthly temperature and mean monthly precipitation during our study (October 2004–September 2006) for Parque Lineal and Canal Blasina sites. We obtained climate data from the Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport, which is located between the two study sites (~1 km, Fig. 1a).

Estimating population densities

Monthly population censuses (N = 24) were performed (October 2004–September 2006) in 1-ha (1 × 0.010 km) transects in Parque Lineal by walking a trail along the edge of the channel, and in Canal Blasina using a canoe. Total number of individual I. iguana observed along the mangrove edge in each transect was recorded. We categorized each observed individual by age class (adult, subadult, juvenile), sex (male or female) and behavior (males in display-bright coloration, basking, mating, foraging and head-nodding). Age class and sex were determined by identifying key physical traits (body, head and femoral pore size, dorsal crest spine length and coloration) as described in Dugan (1982). For standardization purposes a total of nine man-hours were spent in each transect per monthly visit, and only one member of the team assigned age and sex.

Reproductive biology

Male mating behavior serves as a useful tool to determine I. iguana reproductive phenology in a recently invaded location. This species has adapted to synchronize its reproduction with climatic variables, such as temperature and precipitation, conferring an advantage to adults and newborn juveniles (Rand and Greene 1982). During the dry season, male colors intensify and territorial displays are more frequent due to cooler temperatures indicating the beginning of the breeding season (Distel and Veazey 1982; Dugan 1982; Savage 2002). During the wet season, eggs are ready to hatch, the soil around nests has loosened, and new foliage is abundant making it available as a food source and camouflage for neonates (Rand and Greene 1982).

We monitored nesting activity and collected clutch size data from two egg-laying seasons from March to May in 2008 and 2009 at Las Cabezas de San Juan Nature Reserve. At the beginning of the season (March), we identified potential nesting sites and marked them with flags. In 2008, we created artificial mounds near past nesting sites to lure female iguanas, as suggested by Krysko et al. (2007). Towards the end of the egg-laying season (late April and early May), we removed egg clutches from nesting sites and artificial mounds, and recorded depth of the nest and number of eggs per clutch. Egg dimensions (length and width) were obtained by measuring three to five randomly chosen eggs from each clutch with a digital caliper rounded to the nearest hundredth (Digimatic Plastic Caliper; Mitutoyo Corporation). We determined the egg viability per clutch as the percent of eggs in healthy condition (not shriveled or cracked). In addition, we measured the snout to vent length (SVL) of gravid females captured or found dead, with a metric tape measure; and for hatchlings’ SVL we used digital calipers.

Data analysis

Multiple regression analysis was performed to determine the effect of climatic variables on the number of observed individuals of I. iguana (all ages considered), and males in display at Parque Lineal and Canal Blasina. The variables included in the regression model were those identified by Harris (1982) as predictors of I. iguana activity: mean monthly temperature (°C), precipitation (mm) and wind speed (km/h). To meet the assumptions of the regression analysis, the data obtained in Canal Blasina was transformed to log (X + 1). All statistical tests were performed using Minitab Release 15 and α = 0.05.

Since a higher abundance of male I. iguana in reproductive display was found to be a good predictor of a breeding season (Harris 1982; Dugan 1982), we compared the proportion of displaying males in the population (total number of males in display/total individuals observed) between the warm-wet and cool-dry seasons of each sampling period using a 2-Proportion Test at both localities. To answer whether reproductive activity changed over time, we compared the yearly proportions of displaying males (total number of males in display/total individuals observed) in the same season also using a 2-Proportion Test. In addition, we compared the number of I. iguana (total individuals and males in display) using a Mann–Whitney Test to determine differences in population densities between localities (Parque Lineal vs. Canal Blasina) and between sampling periods (I: October 2004–September 2005 and II: October 2005–September 2006).

Results

Population densities of I. iguana at Parque Lineal and Canal Blasina

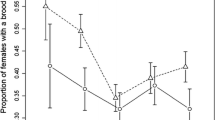

Iguana iguana population densities over time at both study sites reflect fluctuations related to seasonality (Fig. 2a, b). Despite a few anomalies in the mean monthly precipitation, climate data confirmed that there was a consistent pattern of cool temperatures and low precipitation (cool-dry season), and a period of warmer temperatures and higher precipitation (warm-wet season) as shown in Fig. 2c and d, for the years 2004–2006 of this study. Results from the multiple regression analysis (Table 1) revealed that mean monthly temperature was the only predictor that consistently explained both the total number of individuals and the number of males in display observed at Parque Lineal and Canal Blasina. The number of observed individuals increased significantly during the cooler and drier months of the year (Fig. 2; Table 1). Mean monthly precipitation alone was not a good predictor of active males in display at either site, but it is important at predicting total iguana abundance (Table 1). Mean monthly wind velocity explained part of the variation in abundance only at Canal Blasina (Table 1).

Seasonal variation in population densities of Iguana iguana in Puerto Rico. Total number of individuals (a) and total number of males in display (b) are given for Parque Lineal (closed circles) and Canal Blasina (open circles). Dashed lines delimit sampling periods I and II. Climatic variables correspond to mean monthly temperature (c) and mean monthly precipitation (d). The shaded area denotes the cool-dry season, and the white area corresponds to the warm-wet season

Seasonal differences in the proportion of males in reproductive display were significantly higher during the cool-dry season for the two populations of I. iguana studied (Table 2). There was a significant increase in the proportion of males in display from sampling periods I and II within the same season, except in the cool-dry season at Canal Blasina where the rates of display were similar (0.45 vs. 0.46, Table 2). This similarity of reproductive activity between seasons may have influenced our estimation of population increase when considering males in display as an indicator of population size.

The total number of iguana individuals differed significantly (W = 421.5, N = 24, P < 0.0006) between the two study sites (Fig. 2a). A mean monthly count of 64 ± 26 (Range: 20–119) individuals ha−1 were observed in Parque Lineal, while a higher mean of 116 ± 57 (Range: 46–223) individuals ha−1 was observed at Canal Blasina. Figure 2b shows that this trend was also significant (W = 472.0, N = 24, P < 0.0172) for the total number of males in display at each site. The total number of individuals did not differ between sampling periods at either site (Parque Lineal: T = −1.36, N = 12, P = 0.187; Canal Blasina: W = 167.5, N = 12, P = 0.3260), indicating that although the mean number of individuals has increased over the last 30 year (Rivero 1998, Joglar 2005), it was not statistically significant at this time.

Reproductive biology of I. iguana at Las Cabezas de San Juan Nature Reserve (CSJNR)

A total of 102 clutches and 2,558 eggs were found and removed at this site from April–May in 2008 (43 clutches; 1,018 eggs) and 2009 (59 egg clutches; 1,540 eggs). The total average number of eggs per clutch was 24.5, and were found at a mean depth of 35.26 cm (Table 3). Dimensions of eggs had a mean length of 4.04 cm and a width of 2.93 cm (Table 3). The mean egg viability varied from 81.9% in 2008 to 91.4% in 2009, which suggests a high hatching success rate. Mean SVL of gravid females was 34.5 cm, and 6.71 cm for hatchlings (Table 3).

At CSJNR nesting activity lasted from February 13 to April 21 in 2008 and from February 24 to the end of April in 2009. The first hatchlings were observed on May 17 2008 and May 14 2009.

Discussion

Population densities of I. iguana in Puerto Rico

Our transect-based population monitoring of I. iguana in Puerto Rico suggests that this species is extremely abundant at both localities surveyed. At the peak of the breeding season, a maximum of 119 iguanas ha−1 were observed in Parque Lineal, while 223 iguanas ha−1 were observed at Canal Blasina (Fig. 2). Although both localities were similar in forest structure (i.e., channels in mangrove swamps), differences in I. iguana abundance may be due to the proximity to the Piñones State Forest (Fig. 1) and/or different levels of anthropogenic disturbance. Parque Lineal is an isolated area surrounded by urban sprawl, while Canal Blasina is next to the Piñones State Forest, which is a vast protected area with more potential nesting sites. Densities of this invasive reptile were much higher at both of our study sites in Puerto Rico than in localities in its native range where the species was overexploited as a food source (Colombia: 13.7 individuals ha−1; Muñoz et al. 2003), and within the range where it was protected (Panamá: 36–50 adults ha−1, Dugan 1982). Non-native habitats provide a low predation environment and lack of competitors which may influence this species to become abundant in our study sites. A significant increase in the proportion of males in display during the breeding season was observed between sampling periods (Table 2). This may be attributed to an increase in levels of reproductive activity boosted by a higher number of males, or to increased resources, specifically perching sites. The availability of perch sites was not measured in this study, but we infer from our observations that I. iguana foraging cleared mangrove areas that consequently provided more displaying sites. These population trends are of concern, because an increase in reproductive activity suggests future population growth.

Reproductive phenology in Puerto Rico

The reproductive behavior of I. iguana in Puerto Rico was similar to that observed by Dugan (1982) and Harris (1982) in its native range. Fluctuations in the reproductive activity reflected a response of I. iguana to seasonal patterns (Fig. 2), where environmental variables such as temperature, precipitation and wind affected the observed abundance at both study sites (Table 1). During the cooler and drier months of the year (December–February), we observed the highest numbers of individuals and an increase in the displaying activity of males (Fig. 2). This activity attracts females, consequently having an impact on the abundance observed in areas where iguanas congregate for courtship (Dugan 1982; Rodda 1992). The ability to spend more time basking in open areas during cooler and windy periods caused an increase of displaying activity by males (Dugan 1982; Rand and Greene 1982). However, the effect of wind was only significant for the population at Canal Blasina (Table 1), where the channel structure was narrower than in Parque Lineal. In contrast, during the warm-wet season, the observed rates of displaying males significantly decreased (Table 2), possibly because of reduced detectability since they lack the bright coloration typical of the breeding season, and/or the movement to other areas within their range (Rodda 1992). The fact that the total number of individuals at Parque Lineal was similar between reproductive seasons supports the first hypothesis.

Nesting activity started at the end of the cool-dry season (February–April) when iguanas searched for potential sites to lay their eggs. Mean clutch size of I. iguana in Puerto Rico was higher than in other islands in the Caribbean, but lower than in localities in Central and South America (Table 3). As comprehensive reviews of other studies suggest, aspects of the reproductive biology of this species (e.g. number of eggs per clutch, egg dimensions, and mean body size of females and hatchlings) are highly variable throughout its native range (Table 3).

Our 2008–2009 nesting observations at CSJNR suggest that I. iguana is a reproductively successful species, producing more than 100 clutches and 2,558 eggs with a maximum of 91.4% per clutch egg viability at our study site. This reproductive success in combination with the absence of predators is probably a major driver of the population densities we are observing in Puerto Rico (Table 3).

Impacts of an invasive species in Florida and Puerto Rico

Iguana iguana is an invasive species that may threat native biodiversity, infrastructure and human health. Potential impacts of I. iguana (i.e. predation, competition, interbreeding and pathogen introduction) have been reported for localities such as Florida and the Lesser Antilles (Day and Thorpe 1996; Mermin et al. 2004; Meshaka et al. 2007; Krysko et al. 2007; Townsend et al. 2005).

Iguana iguana was first reported in Florida as non-breeding in 1966, becoming a “cute neighbor” between the 1970s and 1980s. After its populations exploded in 1990s, the iguanas soon became a nuisance species (Krysko et al. 2007). Land managers and property owners consider I. iguana a pest because they have caused extensive damage to residential and commercial landscape vegetation, and dig burrows (for nesting and refugia) causing erosion that undermines sidewalks, foundations, canal banks, seawalls, and other infrastructure (Kern 2004; Krysko et al. 2007). In addition, many homeowners despise iguanas because of their unsightly and unhygienic defecations on moored boats, docks, porches, decks, swimming pools and surroundings (Kern 2004; Krysko et al. 2007). As a preventive measure some homeowners have installed wire mesh and/or electric fences in order to protect herbs, flowering shrubs and trees from iguanas. At least two institutions in Florida have reported serious damage and losses to iguanas, the Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden in Miami and Key Deer National Wildlife Refuge on Big Pine Key (Krysko et al. 2007). Although some people enjoy watching I. iguana as long as they do not damage valued plants or property, others are intimidated by these large lizards. This difference in attitude towards iguanas has caused disputes among neighbors since some protect and feed iguanas while others understand the importance of removing this non-indigenous species (Krysko et al. 2007).

Iguana iguana impacts in Puerto Rico are similar to the ones reported in Florida, with some additional problems. Collisions between airplanes and wildlife are a serious safety concern and have economic impacts. A 2-month study conducted to assess the potential of iguanas as an airstrike hazard at the Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport (SJU) showed that a total of six iguana incursions (three times in October and three times on November) caused operations to be halted in portions of the SJU airfield (Engeman et al. 2005). According to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) airstrike database all of the five records of collision with iguanas have occurred at the SJU (Engeman et al. 2005). Thus, it is probable that more strikes with iguanas have occurred at the SJU than have been reported (Engeman et al. 2005). Body weight comparisons between adult iguanas and other known aircraft collision hazards indicated that I. iguana represents a serious airstrike hazard; they rank in the same damaging category as ducks, pelicans and eagles (Engeman et al. 2005). Because of safety and economic implications, Engeman et al. (2005) recommended several management actions such as habitat modification, exclusions and population reduction. In the last few years the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER) launched a population reduction program at the SJU, but numbers and results are not yet known. At the Muñiz Air National Guard Base, a smaller airport in the same area with similar habitat as the SJU, a total of 1,798 iguanas were removed by USDA personnel in 2008 (Pedro F. Quiñones, pers. comm.). This number is higher than in Florida where 824 iguanas were removed by a combination of trapping and incidental roadkills (Smith et al. 2007).

Las Cabezas de San Juan Nature Reserve (CSJNR) in northeastern Puerto Rico has been severely impacted by I. iguana. Every year the digging of burrows as part of the species nesting activity undermines the main road at the reserve. Road repair cost fluctuated between $4000 and $5000 annually in the last 6 years (Elizabeth Padilla, per. comm.). The plant nursery at CSJNR loses over a 1,000 young trees (with an approximate cost of $5000 annually due to iguana herbivory (Elizabeth Padilla, pers. comm.). In addition, iguanas’ burrowing behavior has impacted the landscape around the lighthouse at CSJNR (the second oldest in Puerto Rico).

The potential impact of I. iguana on ecosystems and biodiversity has been suggested at some Puerto Rican sites. The foraging habits of I. iguana have been identified as a source of mortality to black mangrove (Laguncularia racemosa) at the San Juan Bay Estuary (Carlo and García-Quijano 2008). In addition, I. iguana may be attracting non-native predators (dogs, cats, and mongooses) to wildlife refuges and other protected areas. At CSJNR we have observed dogs predating upon female iguanas during the egg-laying season. In the Northeastern Ecological Corridor (NEC) in northeastern Puerto Rico, there is an overlap in reproductive season and nesting sites between I. iguana and Dermochelys coriacea (leatherback turtles). This situation is of concern because: (1) iguanas digging habits could destroy leatherback eggs, and (2) iguanas are attracting predators such as dogs and mongooses, which can feed indiscriminately on both iguana and turtle eggs. At the NEC, dogs have been observed attacking female leatherback turtles (Héctor Horta, pers. comm.). Iguana iguana have been reported to feed on bird eggs and chicks (Schwartz and Henderson 1991; Rivero 1998), and we have been informed of adults feeding on common moorhen (Gallinula chloropus) eggs at Parque Lineal (René Fuentes, pers. comm.).

Local agriculture has also been affected by iguanas damaging and destroying crops. Yams (Dioscorea spp.) and yautias (Xanthosoma spp), two main crops in the southeastern town of Maunabo, Puerto Rico where agriculture is an important component of the local economy have been affected; and in the south pumpkin (Cucurbita spp.) and melons (Cucumis sp.) (Héctor De Jesús García, pers. comm.). Golf courses, an important component of the tourism industry in Puerto Rico, have also been negatively affected by iguanas, and land managers and property owners considered them a nuisance because of considerable damage to landscape vegetation (R. Joglar, pers. obs.).

Management recommendations

Thorough knowledge of the life history of an invasive species should be used to develop an effective management plan (Sakai et al. 2001; Smith et al. 2007). In Puerto Rico, we suggest using what we have learned of I. iguana reproductive phenology as a strategy to control and manage its non-indigenous populations (Fig. 3). Adults are easier to remove during the courtship period, when males are in reproductive displays and more females are found near them. Females can also be captured during this period, and radio-tracked to find potential nesting sites. Searching for nests and creating artificial nesting sites was an efficient approach for obtaining information related to the reproductive biology of this species in our study. Artificial mounds can be effective for collecting and destroying eggs thus, controlling iguana populations (Krysko et al. 2007). However, nesting areas must be carefully searched because destroying nests indiscriminately may risk native species that are also attracted to these sites.

Because of its potential negative impacts on entire ecosystems, to both local biodiversity and to humans, I. iguana populations in Puerto Rico should be managed, especially in localities in which threats have been identified as more imminent. Special areas of concern are airports, agricultural lands, habitats of endangered and/or threatened species, and nature reserves. Accordingly, we recommend that a management plan for the species should be developed taking into consideration the findings of this study.

References

Bomford M, Kraus F, Barry SC, Lawrence E (2009) Predicting establishment success for alien reptiles and amphibians: a role for climate matching. Biol Invasions 11:713–724

Carlo TA, García-Quijano CG (2008) Assessing ecosystem and cultural impacts of the green iguana (Iguana iguana) invasion in the San Juan Bay Estuary (SJBE) in Puerto Rico. Unpublished final report for SJBE. 30 Sep 2008

Casas-Andreu G, Valenzuela-López G (1984) Observaciones sobre los ciclos reproductivos de Ctenosaura pectinata e Iguana iguana (Reptilia: Iguanidae) en Chamela, Jalisco. An Inst Biol (UNAM) Serie Zool 55:253–261

Colón JA (1983) Algunos aspectos de la climatología de Puerto Rico. Acta Cient 1:55–63

Day ML, Thorpe RS (1996) Population differentiation of Iguana delicatissima and Iguana iguana in the Lesser Antilles. In: Powell R, Henderson RW (eds) Contributions to West Indian herpetology: a tribute to A. Schwartz. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, New York, pp 136–137

Distel H, Veazey J (1982) The behavioral inventory of green iguana Iguana iguana. In: Burghardt GM, Rand AS (eds) Iguanas of the world. Noyes Publications, New Jersey, pp 252–270

Dugan B (1982) The mating behavior of the green iguana Iguana iguana. In: Burghardt GM, Rand AS (eds) Iguanas of the world. Noyes Publications, New Jersey, pp 320–339

Engeman RM, Smith HT, Constantin B (2005) Invasive iguanas as an airstrike hazard at Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport, San Juan Puerto Rico. J Aviat Aerosp Educ Res 14:45–50

Ewel JJ, Whitmore JL (1973) The ecological life zones of Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. Research paper ITF-18. USDA, Puerto Rico

Harris DM (1982) The phenology, growth, and survival of the green iguana, Iguana iguana, in northern Colombia. In: Burghardt GM, Rand AS (eds) Iguanas of the world. Noyes Publications, New Jersey, pp 150–161

Hirth HF (1963) Some aspects of the natural history of Iguana iguana on a tropical strand. Ecol 44:613–615

Joglar RL (ed) (2005) Biodiversidad de Puerto Rico. Vertebrados Terrestres y Ecosistemas: Serie de Historia Natural. Editorial Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, Puerto Rico

Kern WH (2004) Dealing with Iguanas in the South Florida Landscape. Fact Sheet ENY-714, entomology and nematology, Florida cooperative extension service, institute of food and agriculture science. University of Florida, Gainesville

Krysko KL, Enge KM, Donlan EM, Seitz JC, Golden EA (2007) Distribution, natural history, and impacts of the introduced green iguana (Iguana iguana) in Florida. Iguana 3:2–17

Loftin H, Tyson EL (1965) Iguanas as carrion eaters. Copeia 1965:515

Mermin J, Hoar B, Angulo FJ (1997) Iguanas and Salmonella marina infection in children: a reflection of the increasing incidence of reptile-associated salmonellosis in the United States. Pediatrics 99:399–402

Mermin J, Hutwagner L, Vugia D, Shallow S, Daily P, Bender J, Koehler J, Marcus R, Angulo FJ (2004) Reptiles, amphibians, and human Salmonella infection: a population-based, case-control study. Clin Infect Dis 383:253–261

Meshaka WE, Smith HT, Golden E, Moore JA, Fitchett S, Cowan EM, Engeman RM, Sekscienski CressHL (2007) Green Iguanas (Iguana iguana): the unintended consequence of sound wildlife management practices in a south Florida park. Herp Conserv Biol 2(2):149–156

Müller HV (1972) Ökologische und ethologische studien an Iguana iguana (Reptilia-Iguanidae) in Kolombien. Zool Bertr 18:109–131

Muñoz EM, Ortega AM, Bock BC, Páez VP (2003) Demografía y ecología de anidación de la iguana verde, Iguana iguana (Squamata: Iguanidae), en dos poblaciones explotadas en la Depresión Momposina, Colombia. Rev Biol Trop 51:229–240

Rand AS, Dugan BA (1980) Iguana egg mortality within the nest. Copeia 3:531–534

Rand AS, Dugan BA (1983) Structure of complex iguana nests. Copeia 3:705–711

Rand AS, Greene HW (1982) Latitude and climate in the phenology of reproduction in the green iguana (Iguana iguana). In: Burghardt GM, Rand AS (eds) Iguanas of the world. Noyes Publications, New Jersey, pp 142–149

Rivero JA (1998) The amphibians and reptiles of Puerto Rico, 2nd edn. Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico

Rodda GH (1992) The mating behavior of Iguana iguana. Sm C Zool 534:1–38

Rodda GH, Jarnevich CS, Reed RN (2009) What parts of the US mainland are climatically suitable for invasive alien pythons spreading from everglades national park? Biol Invasions 11:241–252

Sakai AK, Allendorf FW, Holt JS, Lodge DM, Molofsky J, With KA, Baughman S, Cabin RJ, Cohen JE, Ellstrand NC, McCauley DE, O’Neil P, Parker IM, Thompson JN, Weller SG (2001) The population biology of invasive species. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 32:305–332

Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica: a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Savidge JA (1987) Extinction of an island forest avifauna by an introduced snake. Ecol 68:660–668

Schwartz A, Henderson RW (1991) Amphibians and reptiles of the West Indies-descriptions, distributions, and natural history. University of Florida Press, Florida

Smith HT, Golden E, Meshaka WE (2007) Population density estimates for a green iguana (Iguana iguana) colony in a Florida State Park. J Kans Herpetol 21:19–20

Southeast Regional Climate Center (2010) 1971–2000 monthly climate summary for San Juan, PR. http://www.sercc.com/cgi-bin/sercc/cliMAIN.pl?pr8808. Accessed 01 June 2010

Thomas R, Joglar RL (1996) The herpetology of Puerto Rico: past, present and future. In: Figueroa J (ed) The scientific survey of puerto rico and the virgin islands: an eighty-year reassessment of the island’s natural history. The New York Academy of Sciences, New York, pp 181–200

Townsend JH, Krysko KL, Enge KM (2003) Introduced iguanas in southern Florida: a history of more than 35 years. Iguana 10:111–118

Townsend JH, Slapcinsky J, Krysko KL, Donlan EM, Golden EA (2005) Predation of a tree snail Drymaeus multilineatus (Gastropoda: Bulimulidae) by Iguana iguana (Reptilia: Iguanidae) on Key Biscayne, Florida. Southeast Nat 4:361–364

van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Albers KB (1993) Reproductive adaptations of the green iguana on a semiarid island. Copeia 3:790–798

Wiewandt AT (1982) Evolution of nesting patterns in iguanine lizards. In: Burghardt GM, Rand AS (eds) Iguanas of the world. Noyes Publications, New Jersey, pp 119–139

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Velez, L. Santiago and many Joglar/Burrowes Lab students for assistance in the field. Compañía de Parques Nacionales de Puerto Rico, the Conservation Trust of Puerto Rico and its staff at Las Cabezas de San Juan Nature Reserve allowed us to use their facilities as our study sites. Valuable information was kindly provided by H. Horta, L. J. Rivera Herrera, R. Fuentes, E. Padilla, H. De Jesús García and P. F. Quiñones (USDA-WS). P. Burrowes, K. Levedahl, E. Torres and two anonymous reviewers contributed comments that improved earlier versions of this manuscript. Funding was provided by NSF-Funded PRLSAMP (Grant no. HRD-0114586), Proyecto Coquí, and the Conservation Trust of Puerto Rico. Specimens were collected under Puerto Rican Department of Natural Resources permit DRNA: 2009-IC-013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

López-Torres, A.L., Claudio-Hernández, H.J., Rodríguez-Gómez, C.A. et al. Green Iguanas (Iguana iguana) in Puerto Rico: is it time for management?. Biol Invasions 14, 35–45 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-011-0057-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-011-0057-0