Abstract

Men of color who have sex with men (MCSM) commonly experience sexual racism within the community of men who have sex with men (MSM) and are often rejected as potential sexual and romantic partners as a result. The present study quantitatively investigated whether MCSM experience more race-based sexual discrimination relative to White MSM and whether there is an association between experiences of race-based sexual discrimination and two indicators of psychological well-being, namely self-esteem and life satisfaction. Participants were 1039 Australian MSM (774 White MSM, 265 MCSM) recruited from Grindr, a popular mobile geosocial networking app for MSM, who reported their experiences of race-based sexual discrimination, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. Results showed that MCSM experienced significantly more race-based sexual discrimination relative to White MSM, and that race-based sexual discrimination was significantly associated with lower self-esteem and, in turn, lower life satisfaction. These results further corroborate past qualitative work that has long suggested a link between sexual racism and psychological well-being for MCSM. Implications and future directions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Discrimination in the domain of dating and attraction on the basis of racial identity has been termed sexual racism (Stember, 1978). Sexual racism commonly manifests as sexual and romantic rejection of members of certain racial groups as potential partners (Han, 2007). This type of discrimination is prevalent, especially within the community of men who have sex with men (MSM; Callander, Newman, & Holt, 2015; Han, 2007; Paul, Ayala, & Choi, 2010). The past research suggests that sexual racism may have a detrimental impact on the psychological well-being of men of color who have sex with men (MCSM), who are disproportionately affected by it. To date, however, little research has explored this link quantitatively. The present study therefore contributes to this literature by investigating whether MCSM experience more race-based sexual discrimination relative to White MSM and whether there is an association between experiences of race-based sexual discrimination and psychological well-being, specifically self-esteem and life satisfaction.

Sexual Racism

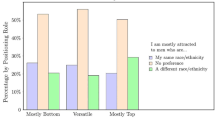

The race-based exclusion of potential sexual and romantic partners is prolific in the MSM community. There is evidence that men seeking men are more likely to focus on race when assessing the characteristics of potential partners than men seeking women (Phua & Kaufman, 2003). MSM themselves perceive that the incidence of sexual racism is higher within the MSM community compared to the heterosexual community (Plummer, 2007). The targets of sexual racism are predominantly men of color (Callander, Holt, & Newman, 2016; Han, 2007; Paul et al., 2010). White men, conversely, are systematically favored and largely desired (Han & Choi, 2018). There is evidence that a racial hierarchy of desire exists within the gay community in Western societies such as the U.S. and Australia, where White men are considered the most desirable and men of color are considered less so, with Black and Asian men relegated to the bottom of the hierarchy (Callander et al., 2016; Han 2008a, 2008b; Han & Choi, 2018; Paul et al., 2010; Plummer, 2007; Wilson et al., 2009). Even MCSM are themselves likely to idealize White men and reject members of their own race as well as other racial minority groups (Han & Choi, 2018; Rafalow, Feliciano, & Robnett, 2017). Thus, sexual racism is not merely random “personal” preference; patterns of sexual racism align with broader systemic racial politics that privilege racial majorities and disadvantage racial minorities.

Sexual racism emerges in a variety of social contexts for MCSM. Although it is sometimes experienced in person (e.g., gay clubs, bars, and saunas), many report that it is more visible and evident in online spaces (Paul et al., 2010; Plummer, 2007). Through dating sites and geosocial networking applications (e.g., Grindr), many MSM routinely engage in discriminatory behavior in their sexual practices that reflect underlying racial bias (Callander et al., 2015, 2016; Paul et al., 2010; Rafalow et al., 2017; Robinson, 2015; Thai, Stainer, & Barlow, 2019). For example, racial preferences are often revealed conversationally or disclosed within profiles found on such dating platforms, framed either as partiality toward members of certain racial groups or exclusion of members of certain racial groups (Callander, Holt, & Newman, 2012). Again, such preferences align with the racial hierarchy of desire, disproportionately communicating an exclusive desire for White men (e.g., “White guys only”) and the disqualification men of color (e.g., “No Asians or Blacks”; Callander et al., 2012; Rafalow et al., 2017).

Thus, the literature strongly suggests that MCSM are sexually and romantically penalized in a community that prioritizes and idealizes White men. There is evidence that MCSM are acutely aware of their predicament in the domain of dating and attraction. Qualitative research consistently shows that gay men of color consistently report greater experiences of sexual and romantic rejection based on their race, and greater difficulty attracting potential partners, than their White counterparts (Han, 2007; Han & Choi, 2018; Plummer, 2007). In fact, sexual racism of this form is largely indistinguishable from general experiences of racial discrimination (Callander et al., 2016). As such, it is likely that experiences of sexual racism would take a toll on the psychological well-being of MCSM. Although sparse, there is some emerging evidence that sexual racism does produce negative psychological consequences for those who experience it.

Sexual Racism and Psychological Well-Being

The broader literature on racism clearly demonstrates that experiences of racial discrimination can exert a negative influence on psychological well-being, heightening depression, anxiety, and distress, and lowering self-esteem and life satisfaction (Schmitt, Branscombe, Postmes, & Garcia, 2014). The negative effects of perceived discrimination on depression and anxiety have also been established within MSM communities, specifically (Choi, Paul, Ayala, Boylan, & Gregorich, 2013). Despite this overwhelming evidence for the association between general forms of racial discrimination and psychological well-being, there is a dearth of work that has examined the link between sexual racism, in particular, and psychological well-being.

Given that researchers have argued the experience of sexual racism is analogous to general experiences of racial discrimination (Callander et al., 2016), it would be logical to propose that exposure to sexual racism would be similarly linked to psychological well-being. Accordingly, qualitative research consistently suggests that the marginalization MCSM feel as a result of their experiences of sexual racism has a detrimental psychological impact (Han, 2007; Han & Choi, 2018; Paul et al., 2010; Ro, Ayala, Paul, & Choi, 2013). In the only study to the author’s knowledge that has quantitatively and directly examined the link between sexual racism and psychological well-being, Bhambhani, Flynn, Kellum, and Wilson (2018) found in a sample of 439 MCSM that experiences of sexual racism predicted greater psychological distress, specifically depression, anxiety, and stress. Further work is required to extend this work and build upon the evidence linking sexual racism and psychological well-being.

Whereas previous research has examined whether sexual racism promotes negative indicators of psychological well-being like depression and anxiety, no extant quantitative work has investigated whether sexual racism is associated with a decrease in positive indicators of psychological well-being, such as self-esteem and life satisfaction. Self-esteem has been defined as one’s global sense of self-worth (Rosenberg, 1965). Qualitative work has indicated that experiences of sexual racism may lead men to question their own worth and desirability, thereby negatively impacting on their self-esteem (Han, 2007; Ro et al., 2013). To the extent that sexual racism predicts lower self-esteem, it should also, in turn, predict lower life satisfaction, given the reliable link between self-esteem and life satisfaction in the psychological literature (Campbell, 1981; Diener & Diener, 1995). The link between sexual racism and life satisfaction, however, has not yet been empirically examined.

The Present Research

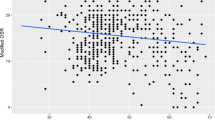

The present study aimed to investigate the link between experiences of race-based sexual discrimination and two indices of psychological well-being that have yet to be examined quantitatively in this context—self-esteem and life satisfaction. The following research questions were explored: Do MCSM report greater experiences of race-based sexual discrimination than White MSM? Is the experience of race-based sexual discrimination linked to lower self-esteem and lower life satisfaction? It was hypothesized that participants of color would report greater experiences of race-based sexual discrimination than White participants. It was also predicted that experiences of race-based sexual discrimination would be negatively associated with self-esteem and life satisfaction. The proposed model linking minority status, experienced race-based sexual discrimination, self-esteem, and life satisfaction is displayed in Fig. 1.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The study was a cross-sectional, internet-based survey conducted in Australia. Australian participants were recruited via an advertisement broadcasted nationally on Grindr, a popular mobile geosocial networking app for MSM. Grindr has been recommended as a high quality participant recruitment platform for MSM (Koc, 2016). Participants were offered the chance to go into a draw to win one of multiple $50 AUD gift cards as an incentive for participation. Participants who responded to the advertisement on Grindr were directed to the online survey. After providing informed consent, they were asked to fill in measures of demographics, experienced race-based sexual discrimination, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. At the end of the survey, participants were given the opportunity to submit their personal details in a separate survey to go into the prize draw. The online survey platform was configured to prevent the same IP address from accessing the survey multiple times. The study was approved by the institution at which it was conducted.

A total of 1210 individuals clicked on the Grindr advertisement, and 1141 entered the survey. Incomplete responses from 98 participants were removed, leaving 1043 participants. Given that the present study focused on MSM, data from four participants identifying as transwomen were also excluded for a final sample of 1039 participants (Mage = 35.94, SD = 12.36). Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are displayed in Table 1. The majority of participants were White, cismen, gay, and single.

Measures

Demographic variables Participants were asked to indicate their race (White, Asian, South Asian, Latino, Middle-Eastern, Black, Indigenous/Maori/Islander, mixed, other), gender (cisman, ciswoman, transman, transwoman, other), age, sexual orientation (gay, bisexual, straight, other), relationship status (single, partnered, married, other), and education (no schooling completed, primary school, high school, trade/technical/vocational training, diploma or equivalent, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, doctorate degree).

Race-based sexual discrimination Three items were developed to measure participants’ experiences of race-based sexual discrimination (i.e., “How often are you rejected in the domain of sex and dating due to your race?”, “How often are you discriminated against in the domain of sex and dating due to your race?”, “How often do you feel disadvantaged in the domain of sex and dating due to your race?”; 1 = never, 5 = always). These items were constructed based on the past research in the area of sexual racism (Callander et al., 2016; Han, 2007; Paul et al., 2010) with wording adapted from Flores et al.’s (2008) measure of perceived discrimination. Responses were averaged such that higher scores reflected greater experience of race-based sexual discrimination. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was .92.

Self-esteem Ten items adapted from the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1965) were used to measure participants’ global self-esteem (e.g., “I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others.”; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Responses were averaged, such that higher scores indicated greater self-esteem. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was .90.

Life satisfaction Five items adapted from the Satisfaction with Life scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) were used to measure participants’ global judgments of satisfaction with their life (e.g., “In most ways my life is close to my ideal.”; 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Responses were averaged, such that higher scores indicated greater life satisfaction. The Cronbach’s α for this scale was .88.

Analysis Plan

SPSS was used to analyze the data. First, a series of analyses of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine differences between participants of color and White participants on experienced race-based sexual discrimination, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. A supplementary series of ANOVAs was run comparing the same variables between each racial minority subsample separately. Given that our focal hypotheses concerned the difference between participants of color and White participants more broadly, and that there were not enough participants within each racial minority subgroup for a reliable comparison, the results for these supplementary ANOVAs are reported in supplementary materials only.

Zero-order correlations were also run to examine the relationships between experienced race-based sexual discrimination, self-esteem, and life satisfaction separately for participants of color and White participants. To test the proposed model linking minority status to life satisfaction via experienced race-based sexual discrimination and self-esteem (see Fig. 1), a serial mediation analysis was conducted using Model 6 of Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and 5000 bootstrapped samples. Bootstrapping in mediation analysis involves randomly sampling from the one dataset with replacement to produce confidence intervals for direct and indirect mediation effects (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

Responses from all participants of color were collapsed into a dummy-coded minority status variable (0 = White participant, 1 = participant of color). All other variables were continuous. The model tested (1) minority status as a predictor of race-based sexual discrimination, (2) minority status and race-based sexual discrimination as predictors of self-esteem, and (3) minority status, race-based sexual discrimination, and self-esteem as predictors of life satisfaction. Direct, indirect, and total effects were examined. Mediation is proposed to occur when the bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals of the indirect effect do not include zero.

Results

Mean Differences and Zero-Order Correlations

A series of ANOVA was conducted to examine differences between participants of color and White participants on experienced race-based sexual discrimination, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. Means and standard deviations split by minority status are presented in Table 2. As expected, participants of color reported significantly greater experiences of race-based sexual discrimination than White participants F(1, 1037) = 651.64, p < .001, η 2p = .39. There was, however, no difference in either self-esteem, F(1, 1037) = 1.30, p = .254, η 2p < .01, or life satisfaction, F(1, 1037) = 1.87, p = .172, η 2p < .01, as a function of minority status.

Zero-order correlations between experienced race-based sexual discrimination, self-esteem, and life satisfaction are displayed separately for participants of color and White participants in Table 3. Experiencing race-based sexual discrimination was significantly and negatively correlated with both self-esteem and life satisfaction. Self-esteem and life satisfaction were also significantly and positively correlated. These associations emerged for both participants of color and White participants.

Serial Mediation Analysis

The pattern of mean differences and bivariate correlations satisfied the requisite links for a full test of the proposed serial mediation model linking minority status, experienced race-based sexual discrimination, self-esteem, and life satisfaction (see Fig. 1). Participants of color reported significantly greater experiences of race-based sexual discrimination than White participants. Experiences of race-based sexual discrimination were significantly associated with self-esteem, which was significantly associated with life satisfaction. Thus, a serial mediation analysis was conducted using Model 6 of Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro to test the proposed model. Figure 2 displays the results of the serial mediation analysis.

Minority status significantly and positively predicted experiences of race-based sexual discrimination, B = 1.38, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [1.27, 1.49], p < .001. Race-based sexual discrimination, in turn, significantly and negatively predicted self-esteem, B = − 0.15, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [− 0.25, − 0.05], p = .002. Finally, self-esteem significantly and positively predicted life satisfaction, B = 0.79, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.74, 0.84], p < .001. As expected, a significant indirect effect of minority status on life satisfaction via experienced race-based sexual discrimination and self-esteem emerged, IE = − 0.16, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.28, − 0.06]. Neither the direct effect, DE = 0.15, SE = 0.09, 95% CI [− 0.03, 0.32], nor total effect was significant, IE = − 0.01, SE = 0.09, 95% CI [− 0.18, 0.17]. Thus, the link between minority status and life satisfaction was completely mediated by experienced race-based sexual discrimination and self-esteem.

Discussion

There is emerging evidence to show that experiences of sexual racism can have implications for the psychological well-being of MCSM (Bhambhani et al., 2018; Han, 2007; Han & Choi, 2018; Paul et al., 2010; Ro et al., 2013). The present study aimed to contribute to this literature by determining whether MCSM experience more race-based sexual discrimination than White MSM and whether this increased exposure to race-based sexual discrimination is associated with two indicators of psychological well-being, namely self-esteem and life satisfaction. Findings demonstrated that MCSM did experience greater race-based sexual discrimination than White MSM and that experienced race-based sexual discrimination was associated with lower self-esteem and, in turn, lower life satisfaction.

The present study is the first to quantitatively demonstrate that MCSM are exposed to more race-based sexual discrimination than White MSM and that this difference is large and statistically significant. This extends upon the previous research which has to date only qualitatively indicated that MCSM may experience greater race-based sexual discrimination than do White MSM (Callander et al., 2016; Han, 2007; Paul et al., 2010). It also provides further support for the notion of a racial hierarchy of desire within the MSM community, wherein White men are considered more sexually and romantically desirable than men of color (Han & Choi, 2018; Paul et al., 2010; Plummer, 2007; Rafalow et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2009). This discrepancy in experienced race-based sexual discrimination between MCSM and White MSM warrants further work to examine the consequences that heightened exposure to sexual racism may have for MCSM.

The previous work has shown that experiences of sexual racism predicts greater psychological distress, specifically depression, anxiety, and stress (Bhambhani et al., 2018). The present study contributes to this work by being the first to quantitatively demonstrate that experiences of race-based sexual discrimination also predict lower self-esteem and life satisfaction. These findings provide quantitative evidence to corroborate a link between sexual racism and self-esteem that has to date only been established qualitatively (Han, 2007; Ro et al., 2013). These findings are also the first to establish a link between sexual racism and life satisfaction. This supports the idea that MCSM, who tend to experience greater sexual racism, may, as a result, question their own desirability and worth, thus undermining their self-esteem and resultant life satisfaction.

There is contention regarding whether discriminating between potential sexual and romantic partners based on race constitutes racism, with some considering it a form of racial bias and others maintaining that it merely reflects benign personal preference (Callander et al., 2015; Thai et al., 2019). The present findings provide further support for the notion that sexual racism is comparable to general racial discrimination. For example, like general forms of racial discrimination, the present findings show that race-based sexual discrimination is experienced disproportionately by MCSM compared to White MSM. This reveals that even in the domain of dating and attraction, there exists a hierarchy that privileges White men. Second, irrespective of whether or not it is defined as racist, sexual racism has the same associations with psychological well-being as general racial discrimination (Choi et al., 2013; Schmitt et al., 2014). Like general forms of racial discrimination, exposure to sexual racism predicts greater depression, anxiety, and stress (Bhambhani et al., 2018), as well as lower self-esteem and life satisfaction.

Thus, the present findings demonstrate that sexual racism is another form of race-based discrimination that needs to be factored in when considering the stressors that racial minority group members face. It is an especially important stressor to consider in the context of intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991). Research shows that having multiple intersecting minority identities puts individuals at greater risk of minority stress (Meyer, Schwartz, & Frost, 2008). MCSM not only face homonegativity as a result of their status as MSM (Meyer, 2013), but also face racial discrimination as a result of their status as people of color (Choi et al., 2013; Schmitt et al., 2014). In addition to this, the present study adds to mounting evidence that MCSM are particularly susceptible to sexual racism, which is heightened in the MSM community (Phua & Kaufman, 2003; Plummer, 2007).

Given that sexual racism is a common occurrence for MCSM and has implications for their psychological well-being, it is imperative that this research is translated into practice to benefit and protect the MCSM in the community. Interventions could be developed to actively discourage practices associated with sexual racism in the MSM community. For example, online dating sites and mobile geosocial networking apps like Grindr are platforms on which dating and other forms of sexual and romantic interactions between MSM most commonly play out. They are also platforms on which sexual racism most frequently emerges (Callander et al., 2015; Paul et al., 2010; Rafalow et al., 2017; Robinson, 2015). Thus, anti-sexual racism messages could be disseminated on such platforms to reduce the occurrence of sexual racism. In 2018, Grindr debuted the “Kindr” initiative, which coincided with an update of the app’s official community guidelines and encouraged users to refrain from engaging in discriminatory behavior on the app (Grindr, 2018). Although there are no data that speak to the effectiveness of the campaign, it is an exemplar of the types of interventions that can be used to mitigate the salience of sexual racism in the lives of MCSM.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present research is not without its limitations, which must be considered when interpreting the above findings. For example, the study design was cross-sectional and correlational in nature. Thus, it is difficult to ascertain the temporal and causal relationships between the measured variables. It should be noted, however, that the proposed directional model linking minority status, experienced race-based sexual discrimination, self-esteem, and life satisfaction is theoretically sound and constructed from a diverse foundation of both qualitative and quantitative research, not only in the literature on sexual racism, but on racial discrimination at large. Nevertheless, it would be important for future research to examine the link between sexual racism and the different indices of psychological well-being longitudinally to determine the temporal nature of the relationships that emerged in this study.

Given that the recruitment advertisement did not specifically call for MCSM, who are, by virtue of their double-minority status, numerically few, the proportion of MCSM participants in the present study was noticeably smaller than the proportion of White MSM participants. As a result, there were not enough MCSM participants belonging to each racial minority subgroup for finer comparisons to be conducted between the different subgroups. Thus, the comparisons between racial minority subgroups reported in the supplementary analyses should be interpreted with caution, even though the findings were largely consistent with the wider literature. Furthermore, it is possible that MCSM differentially experience sexual racism as a function of the particular racial minority subgroup they belong to. For example, the links between sexual racism and the different indices of psychological well-being may be stronger for Asian men than for Latino men, given that Asian men are particularly susceptible to sexual racism due to their lower position in the hierarchy of desire among MSM. Although difficult, future research would benefit from recruiting larger numbers of participants belonging to each racial minority subgroup. Doing so would allow for more nuanced interminority comparisons and race-stratified analyses to help elucidate the differential experiences of sexual racism for MCSM.

Finally, the present study used a measure of race-based sexual discrimination that has not yet been psychometrically validated. Although the measure was constructed based on past work (Callander et al., 2016; Flores et al., 2008; Han, 2007) and yielded results that were in line with the literature at large, it would be beneficial for future work to develop and validate a sexual racism scale. Such a scale would not only be able capture the nuances of sexual racism but would also be a useful tool for researchers who wish to further quantitatively study the causes and consequences of sexual racism. Given that sexual racism is emerging as an important form of racial discrimination to take into account for MCSM and even heterosexual people of color, it is imperative that scholars continue to attempt to understand and tackle it.

References

Bhambhani, Y., Flynn, M. K., Kellum, K. K., & Wilson, K. G. (2018). The role of psychological flexibility as a mediator between experienced sexual racism and psychological distress among men of color who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1269-5.

Callander, D., Holt, M., & Newman, C. E. (2012). Just a preference: Racialised language in the sex-seeking profiles of gay and bisexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality,14(9), 1049–1063. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.714799.

Callander, D., Holt, M., & Newman, C. E. (2016). ‘Not everyone’s gonna like me’: Accounting for race and racism in sex and dating web services for gay and bisexual men. Ethnicities,16(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796815581428.

Callander, D., Newman, C. E., & Holt, M. (2015). Is sexual racism really racism? Distinguishing attitudes toward sexual racism and generic racism among gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior,44(7), 1991–2000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0487-3.

Campbell, A. (1981). The sense of well-being in America: Recent patterns and trends. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Choi, K. H., Paul, J., Ayala, G., Boylan, R., & Gregorich, S. E. (2013). Experiences of discrimination and their impact on the mental health among African American, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Latino men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health,103(5), 868–874. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301052.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Identity politics, intersectionality, and violence against women. Stanford Law Review,43(6), 1241–1299.

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.653.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment,49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Flores, E., Tschann, J. M., Dimas, J. M., Bachen, E. A., Pasch, L. A., & de Groat, C. L. (2008). Perceived discrimination, perceived stress, and mental and physical health among Mexican-origin adults. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences,30(4), 401–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986308323056.

Grindr. (2018). Kindr Grindr. Retrieved January 10, 2019, from https://www.kindr.grindr.com/.

Han, C. S. (2007). They don’t want to cruise your type: Gay men of color and the racial politics of exclusion. Social Identities,13(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630601163379.

Han, C. S. (2008a). A qualitative exploration of the relationship between racism and unsafe sex among Asian Pacific Islander gay men. Archives of Sexual Behavior,37(5), 827–837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9308-7.

Han, C. S. (2008b). No fats, femmes, or Asians: The utility of critical race theory in examining the role of gay stock stories in the marginalization of gay Asian men. Contemporary Justice Review,11(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580701850355.

Han, C. S., & Choi, K. H. (2018). Very few people say “No Whites”: Gay men of color and the racial politics of desire. Sociological Spectrum,38(3), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2018.1469444.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Koc, Y. (2016). Grindr as a participant recruitment tool for research with men who have sex with men. International Psychology Bulletin,20(4), 27–30.

Meyer, I. H. (2013). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity,1(S), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/2329-0382.1.s.3.

Meyer, I. H., Schwartz, S., & Frost, D. M. (2008). Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science and Medicine,67(3), 368–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012.

Paul, J. P., Ayala, G., & Choi, K. H. (2010). Internet sex ads for MSM and partner selection criteria: The potency of race/ethnicity online. Journal of Sex Research,47(6), 528–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903244575.

Phua, V. C., & Kaufman, G. (2003). The crossroads of race and sexuality: Date selection among men in internet “personal” ads. Journal of Family Issues,24(8), 981–994. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X03256607.

Plummer, M. D. (2007). Sexual racism in gay communities: Negotiating the ethnosexual marketplace (Doctoral dissertation, University of Washington). Retrieved from https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/handle/1773/9181.

Rafalow, M. H., Feliciano, C., & Robnett, B. (2017). Racialized femininity and masculinity in the preferences of online same-sex daters. Social Currents,4(4), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329496516686621.

Ro, A., Ayala, G., Paul, J., & Choi, K. H. (2013). Dimensions of racism and their impact on partner selection among men of colour who have sex with men: understanding pathways to sexual risk. Culture, Health & Sexuality,15(7), 836–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2013.785025.

Robinson, B. A. (2015). “Personal preference” as the new racism: Gay desire and racial cleansing in cyberspace. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity,1(2), 317–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649214546870.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Postmes, T., & Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin,140(4), 921–948. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035754.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422.

Stember, C. (1978). Sexual racism: The emotional barrier to an integrated society. New York: Harper & Row.

Thai, M., Stainer, M. J., & Barlow, F. K. (2019). The “preference” paradox: Disclosing racial preferences in attraction is considered racist even by people who overtly claim it is not. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 83, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.03.004.

Wilson, P. A., Valera, P., Ventuneac, A., Balan, I., Rowe, M., & Carballo-Diéguez, A. (2009). Race-based sexual stereotyping and sexual partnering among men who use the internet to identify other men for bareback sex. Journal of Sex Research,46(5), 399–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490902846479.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge Lachlan Macqueen, who assisted with the literature review for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution at which the study was conducted.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thai, M. Sexual Racism Is Associated with Lower Self-Esteem and Life Satisfaction in Men Who Have Sex with Men. Arch Sex Behav 49, 347–353 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-1456-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-1456-z