Abstract

Existing research suggests that young sexual minority Black men (YSMBM) must navigate racialized notions of desirability in the context of sex and intimacy. For YSMBM, identifying as a ‘top’ (i.e., the insertive sexual partner) may grant relative desirability, due to stereotypes that categorize Black men as tops. Thus, sexual positioning might be thought of as one facet of YSMBM’s erotic capital and may have consequences for partner-selection dynamics, such as self-reported subjective racial attraction. Using data from a cross-sectional web-survey of YSMBM (N = 1,778), a chi-square test of independence and multinomial logistic regression were performed to examine whether men’s sexual positioning role (identifying as mostly bottom, versatile, or mostly top) were associated with racial attraction (being mostly attracted to one’s same race, a different race, or having no racial preferences). Compared with men who identified as mostly bottom or versatile, men who identified as mostly top had significantly greater odds of reporting primary attraction to men of a different race/ethnicity than they were to report primary attraction to men of their same race/ethnicity, or to report having no racial preferences. The dynamics of erotic capital at the intersection of race and sexual position may lead to perceptions of (un)desirability among YSMBM, which may, in turn, influence subjective racial attraction differentially across sexual positioning roles. Future research should examine these relationships using more sophisticated study designs and explore implications for mental health and well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The landscape of romantic/sexual partnering among sexual minority (SM) men is highly racialized, with many men of color experiencing and enacting racial exclusion, rejection, and fetishization (e.g., physical objectification) (Wade & Pear, 2022b; Stacey & Forbes, 2022; Wilson et al., 2009). These practices have been amplified in an increasingly hyper-digital age, given that online partner-seeking is highly prevalent among young SM men, and internet users face minimal repercussion for discriminatory behavior perpetuated online. (Wade & Harper, 2020; Badal et al., 2018; Castro & Barrada, 2020; Lapidot-Lefler & Barak, 2012). The extent to which racialized ‘preferences’ are neutral and separable from broader structures of racial prejudice is contentious, given that the experience of racialized sexual discrimination (RSD) has been found to predict negative mental health outcomes, like depression, among young sexual minority Black men (YSMBM) (Wade et al., 2021). Within this broader context of sexual racism, there are behaviors and expressions that afford or constrict Black men’s erotic capital, or embodied sociocultural resources within a sexual field—which can be leveraged to be seen as desirable by sexual partners (Daroya, 2017; Mushtaq, 2021).

In the dating scene of queer men, Black men are stereotyped as being hypermasculine, hypersexual, and sexually aggressive; having large penises; and occupying the sexually insertive anal sex position (i.e., top) (Wilson et al., 2009). Indeed, research has documented instances of Black men being sought out by sexual partners, specifically due to their supposed roles as dominant and sexually aggressive tops (Rafalow et al., 2017; Teunis, 2007). The current literature also documents instances of Black men being explicitly asked by sexual partners to perform these stereotypes, such as being asked to wear a do-rag and Timberland boots during sex (Hammack et al., 2022) or the expectation that they will always be the top (Teunis, 2007). Conversely, Black men have also reported experiencing consistent rejection if they told partners that they preferred the sexually receptive position (i.e., bottom) (Wilson et al., 2009). Seemingly then, these stereotypes are self-perpetuating, creating a paradox where conforming to such stereotypes may increase Black men’s desirability, while simultaneously becoming the only (or predominant) way in which Black men can garner desirability. Particularly, it could be argued that Black men who occupy the sexual positioning role of top have more erotic capital than Black men who occupy the role of bottom.

Attraction and Desirability

Occupying social categories perceived as desirable, and thus, having erotic capital, likely enables individuals to be more selective in choosing romantic and sexual partners. For example, Han (2006) discusses how, because Asian men are stereotyped as being passive and feminine, many SM Asian men in the queer dating scene cannot be agentic in choosing partners, and feel as though they must wait to be chosen by White men. Because SM Black men are often similarly labeled as undesirable (Mushtaq, 2021), it is likely their agency is similarly restricted. This may, in turn, leave YSMBM unable to pursue a more racially diverse pool of partners. Such constraints might be even more present for Black men who bottom, given stereotypes of Black men as tops (Wade & Pear, 2022a; Wilson et al., 2009). Indeed, research finds that, overall, Black men are viewed as less desirable within social and intimate contexts among queer men (Raymond & McFarland, 2009). One qualitative study (N = 111) asked SM men their racial ‘preferences;’ and though the Black men in the sample expressed ‘preferences’ for a more diverse set of racial identities, Black men were the second least ‘preferred’ group (after Asian men) among White and Latino men – and only one Asian man in the sample stated a ‘preference’ for Black men (Wilson et al., 2009). Other researchers highlight instances of overt exclusion and rejection of Black men as intimate partners among queer men (Conner, 2019; Paul et al., 2010).

Additionally, past research has documented pervasive narratives among queer men about what types of men are understood as realistic prospective partners for men of color. For Asian men, research has captured the stereotype that Asian men can only date older White men, based on the idea that those are the only people attracted to Asian men, which then contributes to the stereotype that Asian men are only attracted to older White men (Han, 2008). Other research documents queer men’s use of racialized labels for men based on the racial identities of their partners, such as ‘potato queen’ for men of color dating White men and ‘dinge queen’ for White men (das Nair & Thomas, 2012; Jackson, 2014). This suggests a pervasive tendency to categorize and totalize men based on their partner selection, which may impact Black men and other men of color’s dating practices and ultimately denigrate queer men of color. It might also be the case that SM Black men’s racial ‘preferences’ are tailored to the restrictive stereotypes about who they are attracted to and who might be attracted to them.

Currently, quantitative research examining factors that limit and promote YSMBM’s erotic capital and the impact of YSMBM’s sexual positioning on partner selection dynamics remains sparse. Given the literature referenced, YSMBM’s sexual position can be examined as one facet of their erotic capital, which then impacts sexual/romantic relations and agency. It is likely the case that Black men that top have more erotic capital, relative to Black men who bottom, because they conform to the expectation that Black men only top, and subsequently have more agency in selecting romantic and sexual partners. Because identifying as a top may increase Black men’s relative desirability, sexual positioning roles may be associated with an array of intimacy-seeking outcomes, such as partner selectivity and subjective racial attraction. However, research has yet to examine the relationship between YSMBM’s sexual positioning roles and subjective racial attraction. As an underexamined area of study, it will be important to provide an initial exploration of these relationships. Cross-sectional examinations of these dynamics are a useful first step in developing more pointed research questions, and will establish the groundwork for more rigorous investigations of how race/ethnicity, sexual roles, subjective attraction, and discrimination intersect to contextualize the experiences of sexual minority men who seek partners online.

The Current Study

The current study examines differences in YSMBM’s self-reported subjective racial attraction by sexual position, among a sample of men who use dating/hook-up apps to find partners. Although YSMBM overall may be perceived as less desirable, conforming to racial stereotypes by identifying as tops may allow them to garner more desirability, and thus have more agency in selecting sexual partners. Therefore, we hypothesize that YSMBM who identify as mostly top will be more likely to express subjective racial attraction towards men of other racial identities, due to having more erotic capital.

Method

Participants

Eligibility Criteria

Participants had to meet the following eligibility criteria: (1) identify as a man; (2) be assigned male sex at birth; (3) identify primarily as Black, African American, or with any other racial/ethnic identity across the African diaspora (e.g., Afro-Caribbean, African, etc.); (4) be between the ages of 18 and 29 inclusive; (5) identify as gay, bisexual, queer, same-gender-loving, or another non-heterosexual identity, or report having had any sexual contact with a man in the last 3 months; (6) report having used a website or mobile app to find male partners for sexual activity in the last 3 months; and (7) reside in the United States.

Recruitment

A non-probability convenience sample of YSMBM were recruited using best practices for online survey sampling (Fricker, 2008; Bauermeister et al., 2012), between July 2017 and January 2018. Participants were recruited online to participate in the “ProfileD Study.” Most participants were recruited through Facebook (n = 86.7%) and the gay dating app Scruff (n = 9.5%). Prospective participants viewed advertisements for the study and clicked on a link embedded in the advertisement that directed them to the study webpage. Advertisements on Facebook were only made viewable to men in the targeted age range who lived in the United States. Facebook ads were further tailored to target individuals who (1) indicated that they were “interested in” men, or who omitted information on the gender in which they were interested; (2) indicated interest in various LGBTQ-related pages on Facebook; (3) matched Facebook’s behavior algorithms for U.S. African American Multicultural Affinity; or (4) indicated interest in various pages related to popular Black culture.

Procedure

Prospective participants were directed to a survey hosted on Qualtrics upon clicking on the study advertisement. Participants were presented with a set of screening questions to determine their eligibility. Those who met the eligibility criteria were directed to a consent page, which contained detailed study information (i.e., purpose of the research, description of participant involvement, risk/discomforts; benefits; confidentiality etc.). Those consenting to participate proceeded to the full survey which lasted 30 to 45 min. Participants were not compensated for taking the survey. While completing the survey, participants were permitted to save their answers and return to the survey at a later time if they were not able to complete it in a single sitting. Study data were kept in an encrypted and firewall-protected server, and all study procedures received IRB approval for ethics in human subjects research.

Measures

The self-reported age, relationship status, educational attainment, and sexual orientation of each participant was collected. Participants were instructed to provide their numerical age. Participants were asked to indicate their relationship status by responding to the question, “are you single?” with an answer of 1 = ‘Yes’ and 2 = ‘No.’ Participants could select one of 11 sexual orientation categories (e.g., gay, bisexual, questioning, etc.) and one of five educational attainment categories (e.g., high school graduate, college graduate, etc.). Participants were also asked to describe their sexual role with respect to anal sex. Participants could select one of six options: 0 = ‘I do not have anal sex;’ 1 = ‘Bottom;’ 2 = ‘Versatile Bottom;’ 3 = ‘Versatile;’ 4 = ‘Versatile Top;’ and 5 = ‘Top.’ Finally, participants responded to the prompt, “I am mostly attracted to men who are…” and were provided with three answer choices: 1 = ‘My same race/ethnicity;’ 2 = ‘A different race/ethnicity;’ or 3 = ‘No preference.’

Data Analytic Strategy

A total of 2,188 eligible and consenting participants were recruited for the study. Participants indicating that they did not engage in anal sex (n = 227) were excluded. Participants with missing data were also excluded, resulting in a total of 1,778 participants for analysis. For ease of interpretation, and to align with prior empirical work, participants identifying as bottoms or versatile bottoms (i.e., individuals who predominantly identify as bottom but will occasionally top) were collapsed into a single category, “Mostly Bottom,” while those identifying as tops or versatile tops (i.e., individuals who predominantly identify as top but will occasionally bottom) were collapsed into a single category, “Mostly Top.” Descriptive statistics were computed for the study sample, including mean scores, frequency counts, and percentages for demographic characteristics and study variables.

Chi Square Analyses

To explore differences between sexual positioning roles and racial attraction, a 3 × 3 Chi-Square test of independence was conducted comparing three groups (those who identified as mostly bottom, versatile, or mostly top) across three different categories of racial attraction (being mostly attracted to one’s same race, a different race, or having no racial preferences). A post-hoc test examining the adjusted residuals (Z-scores) was conducted to determine if the observed count differed significantly from the expected count in each cell. To protect against the probability of committing a Type I error, we adjusted the p-value to establish statistical significance (i.e., a Bonferroni correction) by dividing the conventional significance value of 0.05 by the number of cells being tested (Beasley & Schumaker, 1995). The resultant p-value (0.05 / 9) necessary to establish significance was thus p < .00556.

Multivariate Analyses

To examine the association between sexual positioning roles and racial attraction, we performed four multinomial logistic regressions with racial attraction as the dependent variable (DV) and sexual positioning roles entered as independent variables (IV). Two models included primary attraction to those of the same/race ethnicity as the DV referent category (with one model using ‘mostly top’ as the IV referent group and the other using ‘versatile’ as the IV referent group) and the other two models used no racial preferences as the DV referent category (with one model using ‘mostly top’ as the IV referent group and the other using ‘versatile’ as the IV referent group). We also included four covariates in each model: relationship status, age, education, and sexual orientation identity (with gay and bisexual identity entered into the model, and identifying as ‘Other’ serving as the referent group). All data was analyzed using SPSS v. 20.

Results

Chi-Square Analyses

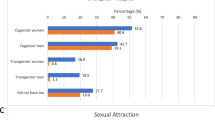

The mean age of the sample was 24.13 years (SD = 3.24). Most participants identified as gay (70.7%) or bisexual (17.0%) and most participants were single (85.9%). Approximately two-fifths of the sample had graduated from college or received a post college education (39.3%), and nearly half (47.5%) of participants had received some college education. A little more than one-third of the sample identified as mostly bottom (35.3%) or mostly top (37.6%); the remaining participants identified as versatile (27.1%). Approximately half of participants (52.9%) indicated that they had no preferences in racial attraction. Among the remaining participants, racial attraction was evenly split between being attracted to men of their same race (23.6%) or men of a different race (23.5%) (see Table 1). The Chi-Square test of independence was significant (χ2 (4) = 22.82, p < .001), indicating that racial attraction differed by sexual position among the study participants. Post-hoc tests indicated that men identifying as mostly top (Count = 196, Expected Count = 156.7) were significantly overrepresented in being attracted to men of a different race/ethnicity (Z = 4.55, adj. p < .00111) (See Table 2; Fig. 1).

Multivariate Analyses

Referent: Primary Attraction to Same-Race

In the models with primary attraction to the same race/ethnicity as the referent category, several covariates emerged as significant. Compared with men identifying as other (sexual orientation), gay men (Exp(B) = 3.12; p < .001) and bisexual men (Exp(B) = 2.55; p < .001) had significantly higher odds of reporting primary attraction to men of a different race/ethnicity than primary attraction to men of the same race/ethnicity. In addition, compared with men who identify as other, gay men (Exp(B) = 2.34; p < .001) and bisexual men (Exp(B) = 2.17; p < .001) had significantly higher odds of reporting no racial preferences than reporting primary attraction to men of the same race/ethnicity. Education also emerged as significant; every unit increase in education was associated with significantly lower odds (Exp(B) = 0.80; p < .05) of reporting no racial preferences than reporting primary attraction to men of the same race/ethnicity.

Compared with men identifying as mostly top, men identifying as mostly bottom (Exp(B) = 0.48; p < .001) and versatile (Exp(B) = 0.49; p < .001) had significantly lower odds of reporting primary attraction to men of a different race/ethnicity than reporting primary attraction to men of the same race/ethnicity. In addition, compared with men identifying as mostly top, men identifying as mostly bottom (Exp(B) = 0.73; p < .001) had significantly lower odds of reporting no racial preferences than reporting primary attraction to men of the same race/ethnicity. Finally, compared with men identifying as versatile, men identifying as mostly top (Exp(B) = 2.05; p < .001) had significantly higher odds of reporting primary attraction to men of a different race/ethnicity than primary attraction to men of the same race/ethnicity (see Table 3).

Referent: No Racial Preferences

In the models with no racial preferences as the referent category, only education emerged as a significant covariate. Every unit increase in education was associated with significantly higher odds (Exp(B) = 1.17; p < .05) of reporting primary attraction to individuals of a different race/ethnicity than reporting no racial preferences. Compared with men identifying as mostly top, men identifying as mostly bottom (Exp(B) = 0.66; p < .01) and versatile (Exp(B) = 0.59; p < .01) had significantly lower odds of reporting primary attraction to men of a different race/ethnicity than reporting no racial preferences. Finally, compared with men identifying as versatile, men identifying as mostly top (Exp(B) = 1.69; p < .001) had significantly higher odds of reporting primary attraction to men of a different race/ethnicity than reporting no racial preferences (see Table 3).

Discussion

The current study aimed to explore the association between sexual positioning and self-reported subjective racial attraction among YSMBM. Nearly an equal amount of YSMBM in the sample identified as mostly bottom (35.3%) and mostly top (37.6%). This is a potentially notable finding given the stereotype that Black men primarily identify as tops (Rafalow et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2009), but is also congruent with prior research indicating that race/ethnicity is not associated with a sexual positioning identity (Moskowitz & Roloff, 2017). Also, in the overall sample, most men reported having no racial preferences (52.9%), while the number of men reporting a same-race preference (23.6%) and a different-race preference (23.5%) were nearly identical. This is also notable, given other research finds that racial ‘preferences’ are common (Wilson et al., 2009) and that many SM men find it appropriate to state racial ‘preferences’ (Callander et al., 2015).

In line with our hypotheses, YSMBM who identified as mostly top had significantly higher odds of reporting subjective racial attraction to men of a different race/ethnicity compared with men who identified as versatile or mostly bottom. These findings align with that of a previous study of Black gay and bisexual Toronto men, which found that Black men who had sex with White and different-race men were more likely to be tops, than those who had sex with Black men (Husbands et al., 2013). This might be interpreted as Black tops having a greater ability to select a more diverse array of partners, due to having more erotic capital by virtue of conforming to the stereotype that Black men are tops. Conversely, YSMBM who identify as mostly bottom or versatile men may have less choice, due to occupying positions outside of the stereotype, and thus having lower erotic capital. YSMBM who identify as mostly bottom may report less subjective attraction to men of a different race, because they perceive the intersection of their race/ethnicity and sexual position to be less desirable to non-Black sexual minority men. Black bottoms might then internalize the notion that men of a different race do not find them attractive, and may be less likely to report subjective attraction to men of a different race as a result. Another possibility is that YSMBM identifying as mostly bottom may have experienced more disproportionate rejection from non-Black men (relative to YSMBM identifying as mostly top) and these experiences may contribute to reporting less different-race subjective attraction. We could also interpret sexual positioning differences in terms of behavior. For example, Black tops are more likely to engage in insertive rather than receptive sex. Because they engage in sexual behavior in line with the broader perceptions of queer men’s communities, this might then create more opportunities to partner with men of another race, relative to YSMBM who identify as mostly bottom or versatile. Having more options for partners, as well as potentially having more actual experiences with men of a different race, may influence Black tops’ self-reported subjective racial attraction to those of a different race.

An alternative explanation, that flips the directionality of the relationship between sexual position and subjective racial attraction, might be that non-Black SM men are more likely to hold stereotypes about Black men as being more likely to embody traits that reflect the archetype of the ‘ideal’ top (e.g., having larger penises, being sexually assertive or psychically imposing). Thus, YSMBM who top are more likely to be sought out by non-Black partners, compared to those who bottom. Being sought out by more men of a different race/ethnicity may then shape Black men’s subjective racial attraction, such that they develop a stronger attraction to men of other races/ethnicities because they perceive themselves as being more attractive, in relative terms, to non-Black men. Though yet to be applied to research with Black men specifically, this notion that people are more likely to be attracted to those who express attraction towards them has been termed reciprocal liking or the reciprocity of liking effect (Montoya & Horton, 2012; Montoya & Insko, 2007). Relatedly, it might be the case that queer men who identify as bottom are interested in seeking out tops, which increases the likelihood that they seek out Black partners, due to the idea that Black men are mostly tops by default. This would thereby increase the racial diversity of the dating pools of Black tops. In line with this, another study examined a small sample of dating profiles of sexual minority men in Boston. They found that identifying as a bottom was associated with greater odds of expressing attraction to Black and Latino men, but not attraction to White or Asian men (White et al., 2014).

Yet another explanation for our findings could be that subjective attraction to a different race and identifying as a top reflects a desire to increase one’s relative erotic capital, rather than actually being perceived as more desirable. In other words, it is possible that YSMBM identify as mostly tops and seek out non-Black partners, because identifying as a top and partnering with men of different race are both perceived as being likely to increase erotic capital. Whereas identifying as a top may be seen as more desirable because it aligns with stereotypes of Black men’s sexual positioning roles, pursuing non-Black men may be seen as such because having a non-Black partner may garner more desirability or elevated social standing relative to having a Black partner. This might be particularly so if different-race attraction is in part expressed as attraction to White men. Indeed, the literature suggests that within queer men’s sexual relations, having a White partner is sometimes treated as a status symbol (Crockett, 2020; Ridge et al., 1999). Even outside of queer men’s communities, the social value in having a White partner has been documented. In one study, researchers interviewed an Asian man, whose family advised him not to break up with a wealthy partner and remarked ‘at least he’s not Black’ (Robinson & Frost, 2018). Other scholars have argued that queer Black men who primarily seek out White partners do so due to internalizing negative stereotypes about themselves, with some stereotypes related to having lower status (e.g., being uneducated, less intelligent) (Han, 2007). Thus, rather than top identification increasing desirability and enabling more choice in partner selection, it may be that both top identification and different-race attraction are implicitly understood as garnering erotic capital, and thus, it is the desire to be seen as more attractive that drives both.

Further, YSMBM identifying as mostly bottoms and versatile did not significantly differ in their reported racial attraction. This is of potential interest given that versatile men would likely engage in insertive sex more frequently than bottoms. We might have expected there to be somewhat of a stair-stepper pattern, wherein tops would be most likely to express different-race attraction, followed by versatile men, with Black bottoms being least likely to express different-race attraction. One possible explanation is that versatile men may not be perceived as being ‘real tops,’ and thus, they’re assigned to the category of bottoms (Elstad, 2021; Kirk, 2016). Other researchers have documented the construction of the top/bottom binary among queer men, such that some men view or feel that they can only be viewed as being one or the other, and that indeed, some versatile men emphasize presenting as more masculine (even such that they appear as tops), due to concerns about being perceived as bottoms (Ravenhill & de Visser, 2018).

In addition to our primary variables of interest, several covariates in our study emerged as significant, and may be worthy of note. Participants identifying as gay or bisexual had higher odds of reporting primary attraction to men a different race or having no racial preferences than reporting primary attraction to men of the same race. These findings might be better understood by turning to an established literature base examining how some Black sexual minority individuals have come to adopt alternative sexual identity labels, such as same gender loving (SGL; Malebranche et al., 2004). SGL and other terms have emerged due to the perception that traditional labels—such as gay, bisexual, and lesbian—reflect Eurocentric conceptions of both sexual and sociopolitical identity that have, historically, not been culturally affirming of Black Americans and other racially minoritized groups (Lassiter, 2015; Tobin & Moon, 2020). Thus, by extension, it is possible that the adoption of traditional gay/bisexual identity labels may reflect greater assimilation into mainstream White LGBTQ culture/community—assimilation that may be associated with a greater propensity for developing attraction towards White or otherwise non-Black partners. This possibility calls for closer investigation of the ways in which identity, cultural, and community involvement intersect to influence subjective attraction among this population.

Educational attainment also emerged as significant in our analyses, albeit in unexpected ways. Curiously, higher education was associated with lower odds of reporting no racial preferences than predominantly same-race attraction, and higher odds of reporting predominantly different-race attraction than no racial preferences. It is not immediately clear why education would be associated with subjective racial attraction in the manner observed, though this finding may point to other factors that may be correlated with education (e.g., social network composition, class/income, workplace environment, place of residence or neighborhood characteristics, etc.) that may exert influence over subjective racial attraction and prospective dating pools. To further clarify these possibilities, it will be important for future research to account for additional variables that may play a role in subjective attraction among sexual minority men of color.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study was limited in that our findings cannot directly shed light on the direction of the association between sexual positioning and subjective racial attraction—whether YSMBM who top are more likely to be selective by expressing different-race attraction, or whether YSMBM who top are most likely to be sought out by non-Black partners. Our use of a convenience sample of predominantly Facebook users also limits the generalizability of our findings. It will be important for researchers to use representative samples and/or multiple recruitment venues in future studies. Additionally, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, we are unable to account for variations in sexual positioning roles over time, though researchers have indicated that several factors (e.g., relationship dynamics with partners, partners’ sexual positioning identities, sexual health status, community norms) may contribute to individuals changing their role in different contexts and at different points in their lives (Pachankis et al., 2013). Future research examining the relationship between sexual positioning and other outcomes of relevance to SM men should employ longitudinal designs or more nuanced assessments of positioning roles.

The potential for social desirability bias in reporting racial attraction is also a potential limitation to note, especially given that a slight majority of participants reported having no racial preference. This potential pattern of overreporting might be expressed disproportionately across sexual positioning roles—specifically, there could be higher concentrations of either same-race or (more likely) different-race attraction for all groups, after accounting for social desirability. It is also possible that no preference was selected by many participants because the other two categories of same- and different-race attraction are unable to capture the complexity of people’s attraction. For example, a man might claim to only be attracted to Black and Latino men, but not attracted to Asian men, and may thus report having no preference—though this also would not be a precise reflection of the nature of their attraction.

By extension, our category of different-race attraction does not distinguish between YSMBM who are attracted to White men and YSMBM who are attracted to men of color of another race. This distinction is important, because while a racial ‘preference’ for White men may reflect internalized racial biases, attraction to men of color of a different race might be interpreted as an appreciation for racial diversity, evidenced by seeking partners outside of one’s typical dating pool. In a similar vein, Le and Kler (2022) found that among a sample of young SM Asian American men, internalized racism was positively associated with having a White dating ‘preference,’ while it was negatively associated with having a same-race dating ‘preference.’ Research has yet to fully examine the nuances of having a White vs. non-White (but not same-race) racial ‘preference’ in the context of sexual racism. Additionally, our item for subjective racial attraction does not clearly distinguish between whether it measures attraction as an attitude or is capturing a pattern of behavior. Specifically, in response to the prompt, “I am mostly attracted to men who are…” participants may have responded based on who they perceive evoke feelings of attraction or based on who they actually have had or pursued sexual relationships with. As such, our interpretations of our results should be taken with some caution. Future analyses should better distinguish and measure these constructs of subjective attraction and patterns of actual and pursued sexual partnering.

In light of an emergent literature demonstrating a link between racialized experiences in partner-seeking contexts and adverse mental health outcomes (Wade et al., 2021; Hidalgo et al., 2020; Thai, 2019), researchers should consider how sexual positioning and subjective racial attraction factor into these associations. In a recent study with YSMBM, we reported that rejection from White partners was not significantly associated with mental health outcomes, though same-race rejection was associated with elevated depressive symptoms (Wade et al., 2021). However, we only tested main effects, and it is possible that sexual positioning and subjective racial attraction may modify these relationships. For example, YSMBM who are predominantly attracted to men of a different race may report worse mental health outcomes when rejected from non-Black men, compared with YSMBM who are predominantly attracted to other Black men. YSMBM who identify as mostly bottom may also be more significantly impacted by rejection than YSMBM who identify as mostly top, given that they have less erotic capital as a bottom. There could also be an interaction effect between sexual positioning and subjective racial attraction, such that Black tops who are predominantly attracted to men of a different-race may report greater frequency of – or stronger negative reaction to – outgroup rejection, compared to Black tops who are predominantly attracted to men of the same-race. This may, in turn, result in differential patterns of mental health outcomes. Figure 2 illustrates these possible scenarios.

Finally, future research on subjective attraction among YSMBM could be strengthened by including measures and analyses of skin tone. Skin tone is another point of within-group variation among Black men, upon which they experience differential treatment, such that those with darker skin tones may face more discrimination and more adverse socioeconomic outcomes (Monk Jr, 2014, 2015). Skin tone may have far reaching implications for Black men’s experiences in the context of intimate partner-seeking, though there is limited research in this area as it pertains to sexual minority men. Though most research on colorism has concluded that those with darker skin tones experience greater marginalization than those with lighter skin tones (Keyes et al., 2020), some scholars have suggested that those with darker skin are perceived to be more masculine (Ford, 2011; Hall, 2015; Joseph-Salisbury, 2018). This may complicate subjective appraisals of attraction, given that masculinity is a privileged characteristic and confers greater erotic capital among sexual minority men. Still, some sexual racism scholars have noted that sexual minority men with darker skin may be seen as less attractive (Jordens & Griffiths, 2022), while other scholars—investigating the associations between skin tone and social/behavioral health outcomes among sexual minority men—have reported null findings (Alon et al., 2019. Given that limited and inconclusive literature in this area, it will be important for researchers to investigate the ways in which skin tone interacts with sexual positioning dynamics and subjective racial attraction among YSMBM and other racially minoritized populations.

Conclusion

To conclude, the current study expands on the body of research examining the association between sexual positioning and subjective racial attraction among YSMBM. We found that YSMBM identifying as mostly top had significantly higher odds of reporting attraction to men of a different race/ethnicity. This study highlights the need to interpret findings on queer men of color’s partnering dynamics within existing racialized contexts of unequal desirability and undesirability. This report also offers new analytic directions for future research in this important yet vastly under-investigated area of study.

References

Alon, L., Smith, A., Liao, C., & Schneider, J. (2019). Colorism demonstrates dampened effects among Young Black men who have sex with men in Chicago. Journal of the National Medical Association, 111(4), 413–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2019.01.011.

Badal, H. J., Stryker, J. E., DeLuca, N., & Purcell, D. W. (2018). Swipe right: Dating website and app use among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 22, 1265–1272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1882-7.

Bauermeister, J. A., Pingel, E., Zimmerman, M., Couper, M., Carballo-Diéguez, A., & Strecher, V. J. (2012). Data quality in web-based HIV/AIDS research: Handling invalid and suspicious data. Field Methods, 24(3), 272–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X12443097.

Beasley, T. M., & Schumacker, R. E. (1995). Multiple regression approach to analyzing contingency tables: Post hoc and planned comparison procedures. The Journal of Experimental Education, 64(1), 79–93.

Callander, D., Newman, C. E., & Holt, M. (2015). Is sexual racism really racism? Distinguishing attitudes toward sexual racism and generic racism among gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 1991–2000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0487-3.

Castro, Á., & Barrada, J. R. (2020). Dating apps and their sociodemographic and psychosocial correlates: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186500.

Conner, C. T. (2019). The gay gayze: Expressions of inequality on Grindr. The Sociological Quarterly, 60(3), 397–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380253.2018.1533394.

Crockett, J. (2020). Damn, I’m dating a lot of White guys: Gay men’s individual narrataives of racial sexual orientation development. In J. G. Smith, & C. W. Han (Eds.), Home and community for queer men of color: The intersectional of race and sexuality (pp. 1–29). Lexington Books.

Daroya, E. (2017). Not into chopsticks or curries’: Erotic capital and the psychic life of racism on Grindr. In D. W. Riggs (Ed.), The psychic life of racism in gay men’s communities (pp. 67–80). Lexington Books.

Das Nair, R., & Thomas, S. (2012). Politics of desire: Exploring the ethnicity/sexuality intersectionality in South and East Asian men who have sex with men (MSM). Psychology of Sexualities Review, 3(1), 8–21.

Elstad, S. (2021). 9 struggles only verse gay guys will understand. HomoCulture. https://www.thehomoculture.com/9-struggles-only-verse-gay-guys-will-understand/.

Ford, K. A. (2011). Doing fake masculinity, being real men: Present and future constructions of self among Black college men. Symbolic Interaction, 34(1), 38–62.

Fricker, R. D. (2008). Sampling methods for web and e-mail surveys. In N. Fielding, R. M. Lee, & G. Blank (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of online research methods (pp. 195–216). Sage.

Hall, R. E. (2015). Dark skin, black men, and colorism in Missouri: Murder vis-à-vis psychological icons of western masculinity. Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men, 3(2), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.2979/spectrum.3.2.27.

Hammack, P. L., Grecco, B., Wilson, B. D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2022). White, tall, top, masculine, muscular: Narratives of intracommunity stigma in young sexual minority men’s experiences on mobile apps. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 2413–2428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02144-z.

Han, C. (2006). Geisha of a different kind: Gay Asian men and the gendering of sexual identity. Sexuality & Culture, 10(3), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-006-1018-0.

Han, C. (2007). They don’t want to cruise your type: Gay men of color and the racial politics of exclusion. Social Identities, 13(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630601163379.

Han, C. (2008). No fats, femmes, or asians: The utility of critical race theory in examining the role of gay stock stories in the marginalization of gay Asian men. Contemporary Justice Review, 11(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580701850355.

Hidalgo, M. A., Layland, E., Kubicek, K., & Kipke, M. (2020). Sexual racism, psychological symptoms, and mindfulness among ethnically/racially diverse young men who have sex with men: A moderation analysis. Mindfulness, 11(2), 452–461.

Husbands, W., Makoroka, L., Walcott, R., Adam, B. D., George, C., Remis, R. S., & Rourke, S. B. (2013). Black gay men as sexual subjects: Race, racialisation and the social relations of sex among black gay men in Toronto. Culture Health & Sexuality, 15(4), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.763186.

Jackson, P. A. (2014). That’s what rice queens study!’ White gay desire and representing Asian homosexualities. Journal of Australian Studies, 24(65), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050009387602.

Jordens, A., & Griffiths, S. (2022). Sexual racism and colourism among Australian men who have sex with men: A qualitative investigation. Body Image, 43, 362–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2019.01.011.

Joseph-Salisbury, R. (2018). Constituting and performing black mixed-race masculinities: Hybridising the exotic, the black monster and the ‘light-skin softie’. Black mixed-race men (pp. 53–84). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Keyes, L., Small, E., & Nikolova, S. (2020). The complex relationship between colorism and poor health outcomes with African americans: A systematic review. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 20(1), 676–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12223.

Kirk, A. (2016). 13 struggles only vers men understand. Pride. https://www.pride.com/sex/2016/11/29/13-struggles-only-vers-men-understand.

Lapidot-Lefler, N., & Barak, A. (2012). Effects of anonymity, invisibility, and lack of eye-contact on toxic online disinhibition. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(2), 434–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.10.014.

Lassiter, J. M. (2015). Reconciling sexual orientation and christianity: Black same-gender loving men’s experiences. Mental Health Religion & Culture, 18, 342–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2015.1056121.

Le, T. P., & Kler, S. (2022). Queer Asian American men’s racialized dating preferences: The role of internalized racism and resistance and empowerment against racism. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000602. Advance online publication.

Malebranche, D. J., Peterson, J. L., Fullilove, R. E., & Stackhouse, R. W. (2004). Race and sexual identity: Perceptions about medical culture and healthcare among black men who have sex with men. Journal of the National Medical Association, 96(1), 97–107.

Monk, E. P. Jr. (2014). Skin tone stratification among Black americans, 2001–2003. Social Forces, 92(4), 1313–1337. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sou007.

Monk, E. P. Jr. (2015). The cost of color: Skin color, discrimination, and health among african-americans. American Journal of Sociology, 121(2), 396–444. https://doi.org/10.1086/682162.

Montoya, R. M., & Horton, R. S. (2012). The reciprocity of liking effect. In M. Paludi (Ed.), The psychology of love (pp. 39–57). Praeger.

Montoya, R. M., & Insko, C. A. (2007). Toward a more complete understanding of the reciprocity of liking effect. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(3), 477–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.431.

Moskowitz, D. A., & Roloff, M. E. (2017). Recognition and construction of top, bottom, and versatile orientations in gay/bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0810-7.

Mushtaq, O. A. (2021). Erotic capital and queer men of color. In C. T. Conner, & D. Okamura (Eds.), The gayborhood: From sexual liberation to cosmopolitan spectacle (pp. 125–141). Lexington Books.

Pachankis, J. E., Buttenwieser, I. G., Bernstein, L. B., & Bayles, D. O. (2013). A longitudinal, mixed methods study of sexual position identity, behavior, and fantasies among young sexual minority men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(7), 1241–1253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0090-4.

Paul, J. P., Ayala, G., & Choi, K. (2010). Internet sex ads for MSM and partner selection criteria: The potency of race/ethnicity online. Journal of Sex Research, 47(6), 528–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903244575.

Rafalow, M. H., Feliciano, C., & Robnett, B. (2017). Racialized femininity and masculinity in the preferences of online same-sex daters. Social Currents, 4(4), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329496516686621.

Ravenhill, J. P., & de Visser, R. O. (2018). It takes a man to put me on the bottom: Gay men’s experiences of masculinity and anal intercourse. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(8), 1033–1047. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1403547.

Raymond, H. F., & McFarland, W. (2009). Racial mixing and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 13, 630–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9574-6.

Ridge, D., Hee, A., & Minichiello, V. (1999). Asian men on the scene: Challenges to gay communities. Journal of Homosexuality, 36(3–4), 43–68. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v36n03_03.

Robinson, R. K., & Frost, D. M. (2018). LGBT equality and sexual racism. Fordham Law Review, 86(6), 2739–2754.

Stacey, L., & Forbes, T. D. (2022). Feeling like a fetish: Racialized feelings, fetishization, and the contours of sexual racism on gay dating apps. The Journal of Sex Research, 59(3), 372–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1979455.

Teunis, N. (2007). Sexual objectification and the construction of whiteness in the gay male community. Culture Health & Sexuality, 9(30), 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050601035597.

Thai, M. (2019). Sexual racism is associated with lower self-esteem and life satisfaction in men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(6), 528–538.

Tobin, T. W., & Moon, D. (2020). How racism and respectability politics shape the experiences of Black LGBTQ and same-gender-loving Christians. In M. Panchuk & M. Rea (Eds.), Voices from the edge: Centering marginalized perspectives in analytic theology (pp. 141–165). Oxford.

Wade, R. M. & Harper, G. W. (2020). Racialized sexual discrimination (RSD) in the age of online sexual networking: Are young Black gay/bisexual men (YBGBM) at elevated risk for adverse psychological health? American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(3-4) 504–523. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12401

Wade, R. M., Bouris, A. M., Neilands, T. B., & Harper, G. W. (2021). Racialized sexual discrimination (RSD) and psychological wellbeing among young sexual minority black men (YSMBM) who seek intimate partners online. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 19, 1341–1356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00676-6.

Wade, R. M. & Pear, M. (2022a). A good app is hard to find: Examining differences in racialized sexual discrimination across online intimate partner-seeking venues. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148727

Wade, R. M. & Pear, M. M. (2022b) Online dating and mental health among young sexual minority Black men: Is ethnic identity protective in the face of sexual racism? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,19(21), 14263. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114263

White, J. M., Reisner, S. L., Dunham, E., & Mimiaga, M. J. (2014). Race-based sexual preferences in a sample of online profiles of urban men seeking sex with men. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 91(4), 768–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-013-9853-4.

Wilson, P. A., Valera, P., Ventuneac, A., Balan, I., Rowe, M., & Carballo-Diéguez, A. (2009). Race-based sexual stereotyping and sexual partnering among men who use the internet to identify other men for bareback sex. Journal of Sex Research, 46(5), 399–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490902846479.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Supervision, Resources, and Project Administration, First Author; Visualization, Writing (Original Draft Preparation), and Writing (Review and Editing), First Author and Second Author. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. RW was responsible for the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by RW. All authors contributed to the first draft of the manuscript. All authors commented and edited previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wade, R.M., Nguyễn, D.M. Does Subjective Racial Attraction Vary by Sexual Position? An Analysis of Young Sexual Minority Black Men. Sexuality & Culture 28, 1775–1791 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10205-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10205-3