Abstract

The current study examined factors that influenced heterosexual male and female raters’ evaluations of male and female targets who were gay or heterosexual, and who displayed varying gender roles (i.e., typical vs. atypical) in multiple domains (i.e., activities, traits, and appearance). Participants were 305 undergraduate students from a private, midwestern Jesuit institution who read vignettes describing one of 24 target types and then rated the target on possession of positive and negative characteristics, psychological adjustment, and on measures reflecting the participants’ anticipated behavior toward or comfort with the target. Results showed that gender atypical appearance and activity attributes (but not traits) were viewed more negatively than their gender typical counterparts. It was also found that male participants in particular viewed gay male targets as less desirable than lesbian and heterosexual male targets. These findings suggest a nuanced approach for understanding sexual prejudice, which incorporates a complex relationship among sex, gender, sexual orientation, and domain of gendered attributes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sexual minorities are often viewed negatively in today’s society. For example, more than 20 % of gay men and lesbians have been victims of violence or property crime, and nearly half have been verbally abused (e.g., Herek, 2009; for a recent review, see Rothman, Exner, & Baughman, 2011). Further, individuals often perceive gay men and lesbians to be psychologically maladjusted (e.g., Boysen, Vogel, Madon, & Wester, 2006). It has been hypothesized that victimization and prejudice lead to higher levels of maladjustment and distress in gay and lesbian populations (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, Keyes, & Hasin, 2010; Herek & Garnets, 2007; Mays & Cochran, 2001; Meyer, 2003).

It remains unclear, however, what motives drive anti-gay prejudice. Herek (2000) outlined several possibilities. For some people, anti-gay attitudes are the result of negative initial interactions with a gay man or lesbian, which are then generalized to the group. For others, anti-gay attitudes are a means of ego-defense, which may reflect concerns related to the individual’s own sexuality. Still others may hold anti-gay attitudes due to a real or perceived discordance between their values and those held by the target group (Herek, 2000).

These three options all assume, at least implicitly, that the negative reactions to homosexuality occur in reaction to sexual orientation per se. That is, negative attitudes, whether based on past experiences, ego defensive reactions, or perceived value discordance, are thought to be provoked by the fact that the target of those attitudes is sexually attracted to same-sex individuals. However, another possible source of anti-gay attitudes is real or perceived gender-role violations on the part of gay and lesbian individuals. Past research has found that gay men and lesbians are viewed as possessing gender atypical attributes; that is, lesbians are presumed to be masculine and gay men to be feminine (e.g., Blashill & Powlishta, 2009a; Kite & Deaux, 1987; Lehavot & Lambert, 2007; Madon, 1997; Taylor, 1983). It should also be noted that there is a kernel of truth to these stereotypes, as gay men report greater feminine attributes compared to heterosexual men, whereas lesbians report greater masculine attributes compared to heterosexual women (e.g., Lippa, 2005). Additionally, there is evidence indicating that individuals negatively evaluate gender atypical targets, regardless of their sexual orientation (e.g., Blashill & Powlishta, 2009b). Thus, it is possible that anti-gay prejudice also results from negative reactions to real or perceived violations of gender roles rather than from negative reactions to homosexuality, in and of itself. The aim of the current study was to examine the relative influence of sexual orientation and various types of gender role violations on the evaluations of male and female targets.

Sex of Rater and Sex of Target Differences in Sexual Prejudice

Although anti-gay attitudes are not uncommon, the extent of such attitudes varies considerably depending on characteristics of the attitude holder and target. Heterosexual males and females appear to differ in their attitudes, with males holding more negative attitudes toward gay males and lesbians than do females (e.g., Herek, 1988, Studies 2 and 3, 2000; Herek & Capitanio, 1999; Ratcliff, Lassiter, Markman, & Snyder, 2006, Whitley, 2001). The sex of the target also impacts the degree of sexual prejudice that is typically found. Specifically, results from studies including both male and female participants have found that gay males are viewed more negatively than lesbians (e.g., Herek, 2000; Kite & Whitley, 1998; Whitley, 2001).

Although the patterns described above have routinely been found, there are some instances in which the interaction of sex of rater and sex of target provides exceptions to these findings. For example, the pattern of gay males being evaluated more negatively than lesbians is seen more strongly among heterosexual males than among heterosexual females (e.g., Herek, 1988; Kerns & Fine, 1994; Kite & Whitley, 1998). Furthermore, the typical pattern of males showing more sexual prejudice than females is not always seen when examining reactions to lesbians. Some studies (e.g., Kerns & Fine, 1994; Kite & Whitley, 1998) have found no significant sex differences in attitudes toward lesbians.

Attitudes Toward Gender Roles

In today’s culture, violations of gender roles are viewed negatively. In controlled laboratory studies, in which participants are presented with gender-typical (i.e., feminine females, masculine males) and atypical (i.e., masculine females, feminine males) targets, atypical targets were found to elicit more negative reactions (e.g., Blashill & Powlishta, 2009b; Lehavot & Lambert, 2007; Watterson & Powlishta, 2007). Even though both males and females give and receive negative evaluations regarding gender role violations, these evaluations tend to be stronger in males compared to females (e.g., Sirin, McCreary, & Mahalik, 2004). As with evaluations of gay men and lesbians, the sex of the target also impacts evaluative ratings of gender atypical individuals. Gender role violations in males tend to be viewed far more negatively than gender role violations in females (e.g., Levy, Taylor, & Gelman, 1995; McCreary, 1994).

Some have argued that femininity may be viewed less favorably than masculinity due to its standing in regard to status (e.g., David, Grace, & Ryan, 2004; Powlishta, 2004). In McCreary’s (1994) review of the literature, it was found that stereotypically masculine characteristics were viewed as more socially desirable than feminine characteristics. In fact, Blashill and Powlishta (2009b) found that feminine male targets were viewed as being less intelligent and more boring than masculine males, perhaps tapping into this sense of “devaluing” femininity.

Another possible reason why femininity in males is viewed more negatively than masculinity in females is due to presumptions regarding sexual orientation. For instance, McCreary (1994) designed a study to determine whether males were viewed more negatively than females for violating gender roles because femininity was perceived as lower status (i.e., less desirable) than masculinity or because perceivers viewed effeminate males (more than masculine females) as gay. Participants were presented vignettes describing male or female, 8- or 30-year-old targets as either masculine or feminine; participants then rated their approval of the target’s behavior and the likelihood that the target currently was or would become gay. Although masculine behavior was not seen as generally more desirable than feminine behavior, participants were more likely to perceive male than female targets who violated gender roles as being gay. McCreary concluded that feminine males were rated negatively because of assumptions about their sexual orientation; that is, feminine men and boys were assumed to be gay. Thus, because gender atypical males are viewed to be gay, and because sexual prejudice tends to be highest among heterosexual men, one explanation for the particularly negative reactions to gender role violations by and towards males is that such reactions are actually elicited by presumed homosexuality.

Domain of Gender Role Violation

Recent research has also examined the influence of the type of gender role violation on evaluations of targets. For example, Horn (2007) found that, when comparing appearance and activity gender role violations, both male and female high school students viewed appearance violations as less desirable. This trend was also found for both gay and heterosexual targets of both sexes. This pattern suggests that appearance-related gender role violations may be of utmost importance when evaluating males and females, regardless of sexual orientation.

Attitudes Toward Gender Roles and Sexual Orientation

Thus far, attitudes toward homosexuality and gender role violations have been discussed separately. However, as mentioned earlier, it is hard to separate these two constructs because information about one influences perceptions of the other. Therefore, apparent reactions to gender role violations might actually represent negative reactions to assumed homosexuality (and vice versa). Thus, to properly answer the question “Why are gay individuals viewed negatively?”, both sexual and gender role orientation need to be examined and controlled for simultaneously.

To date, there have been few studies that have examined participants’ attitudes both toward targets of varying sexual and gender role orientations. In one study (Schope & Eliason, 2004), participants read vignettes that described either a masculine or feminine gay male or lesbian and then rated their anticipated behavior toward and comfort with the depicted target. Out of 15 outcome measures, the feminine gay male target was viewed as less desirable than the masculine gay male target on only one item among male participants, with no significant differences being found for the female participants. Male participants’ attitudes were more negative toward the masculine than the feminine lesbian on 6 of the 15 measures. Female participants found the masculine lesbian to be less desirable on three of the 15 outcome variables. Because no heterosexual targets were included for comparison in this study, it is impossible to determine whether, and to what extent, participants were actually reacting negatively to the sexual orientation of targets.

Lehavot and Lambert (2007) expanded on the methodology of Schope and Eliason (2004) by including heterosexual targets in addition to gay and lesbian targets. Results revealed that gay targets were viewed more negatively than heterosexual targets. However, this occurred only for individuals who were high in anti-gay prejudice. When immorality ratings were examined as the outcome variable, a significant 4-way interaction was found. Specifically, Lehavot and Lambert found that, for high prejudiced participants, feminine gay males and masculine lesbians were viewed as more immoral than their heterosexual, gender atypical counterparts. It was also found that high prejudiced individuals rated gay male and lesbian targets as less masculine and feminine, respectively, compared to their heterosexual counterparts (controlling for gender typicality). In sum, the results suggest that individuals with generally negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbians rated specific gay targets negatively, and that when perceived immorality was examined, gender atypical gay targets were viewed more harshly than their gender atypical heterosexual counterparts by highly prejudiced individuals.

In the most recent study examining the influence of gender role and sexual orientation on target evaluations, Blashill and Powlishta (2009b) randomly assigned participants to rate one of six possible male targets: masculine gay, masculine heterosexual, masculine unspecified sexual orientation, feminine gay, feminine heterosexual, and feminine unspecified sexual orientation. Participants then rated targets on a series of evaluative questions. Results revealed that feminine and gay targets were viewed more negatively than masculine and heterosexual (or unspecified) targets. This pattern held regardless of the overall level of anti-gay prejudice in the participant. Furthermore, feminine targets were viewed more negatively than masculine targets on all five outcome variables, whereas the gay targets were evaluated negatively, but not necessarily viewed as possessing negative traits relative to heterosexual targets. These results suggest that both femininity and homosexuality had an independent negative impact on evaluations of men; however, femininity may actually be viewed more negatively and certainly more consistently so (Blashill & Powlishta, 2009b). However, despite these provocative findings, because female targets were not included, it is unclear whether negative reactions to the feminine men were because they were violating traditional gender roles or whether they reflected generally negative views about feminine characteristics. Furthermore, the feminine male targets were described as violating gender roles concerning their preferred activities, desired occupations, and personality traits (i.e., all three types of gender role violations were included in a single vignette). Therefore, it is unclear which aspects of femininity contributed to their negative evaluations. Finally, only male participants were included. To explore whether these findings would extend to masculine female and/or lesbian targets or to female participants, and to determine what domains of gender role violations are viewed most negatively, additional studies in this area are needed.

The Current Study

The current study was designed to identify factors that influence heterosexual male and female raters’ evaluations of male and female targets who are gay or heterosexual and who display varying gender roles in multiple domains. Only a few past studies have controlled for possible confounds in assessing attitudes towards homosexuality, such as gender typicality (Blashill & Powlishta, 2009b; Lehavot & Lambert, 2007) and sex of rater and target (Lehavot & Lambert, 2007), and no published study has included these factors in addition to gender role domain, a salient factor in attitudes toward gender role violations (Horn, 2007). Thus, the current study seeks to replicate findings from the few prior studies, as well as add to the literature base by including the novel factor of gender role domain. The following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1

A 2-way interaction between sex of target and target gender role was expected, with gender atypical targets being viewed more negatively (relative to typical targets) when the target is male.

Hypothesis 2

A 2-way interaction between sex of rater and target gender role was expected, with male participants viewing gender atypical targets (relative to gender typical targets) more negatively than do females.

Hypothesis 3

A 2-way interaction between target gender role and domain was expected, with gender atypical targets being viewed more negatively (relative to gender typical targets) in the appearance domain than in the other domains.

Hypothesis 4

A 3-way interaction between sex of rater, sex of target, and sexual orientation of target was also explored. Male participants may view gay male targets more negatively than gay female targets. Due to inconsistent findings in the literature, however, this was a tentative hypothesis.

Method

Participants

Participants were 305 undergraduate male (n = 116) and female (n = 189) students from a private, Midwestern Jesuit university. The average age of participants was 19.45 years (SD = 1.97) years. Further, participants largely identified as being exclusively heterosexual, with a mean sexuality rating of 1.26 (SD = 0.94) on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 indicating “heterosexual only” (see below). In fact, only 11 participants (3.6 %) identified as non-heterosexual (i.e., rating >1). Participants most often identified with being Caucasian (230; 75 %); however, other ethnicities were also endorsed: Asian (43; 14 %), Other (9; 3 %), African American/Black (8; 3 %), Hispanic/Latino(a) (8; 3 %), Multiethnic (4; 1 %), Native American (2; 1 %), and Native Hawaiian (1; < 1 %).

Procedure

We recruited participants through the university based subject pool. Participants read and responded to all study variables and questionnaires online. Initially, participants read a recruitment statement that explained the purpose of the current study. If participants agreed to continue, they were taken to the first page of the study, which presented the cover story. The cover story described that the participants would be completing self-descriptive measures and rating other participants (targets) in terms of desirability of working with them, with the possibility that the participant would return to complete a problem-solving task with another participant (target) with whom they “matched.” The participants were under the guise that the vignettes were based on aggregated data from the targets’ self-descriptive measure and that the self-descriptive measure that the participant completed would also be aggregated into vignette form for ratings to be made on them by other participants at a later date.

After reading the cover story, participants indicated via free response the name and relation of an individual with whom they spent a majority of their free time with, as well as some activities that they did with this individual. This information was needed to increase the realism of the cover story. Then, participants read a brief vignette about a given target (varying in terms of sex, sexual orientation, gender role typicality, and gender role domain attribute), followed by questions designed to assess their evaluation of the target. Next, participants completed manipulation check questions. Finally, participants completed a brief demographic form and a measure of sexual orientation. After all measures were completed, participants were debriefed about the true nature of the study.

Measures

Vignettes

For each of the conditions in the study, a vignette describing the relevant target was presented. The vignette included statements describing the targets’ gender role characteristics in one of three domains (activities, traits or appearance), the targets’ sex, sexual orientation, and gender-neutral “filler” information about the target. In order to create empirically-derived masculine and feminine vignettes, activity and trait items were selected from the OAT (Occupations, Activities, and Traits) (Liben & Bigler, 2002). The appearance items were selected from a parallel measure that is currently under development, which assesses cultural gender stereotypes of appearance and physically-related attributes (Powlishta, Watterson, Blashill, & Kinnucan, 2008). The vignettes included three masculine (goes fishing, builds with tools, and fixes cars) or three feminine (bakes cookies, baby-sits, and reads romance novels) activities, three masculine (brave, adventurous, and brags a lot) or three feminine (emotional, shy, and talkative) traits, or three masculine (deep voice, broad shoulders, and rough hands) or three feminine (hips sway when walking, plucked eyebrows, and delicate) physical/appearance-related items. Within each domain, items were selected so that masculine and feminine items would match in terms of their average degree of gender stereotypicality based on cultural stereotype ratings provided by 120 undergraduate students from Liben and Bigler’s (2002) sample (activities and traits domains) or on analogous ratings from 142 undergraduates in the Powlishta et al. (2008) study (appearance domain). Attempts were also made to match the average degree of gender stereotypicality across domains; however, this matching was difficult to accomplish. Activity and appearance items had similar average ratings of stereotypicality (M’s = 2.00 and 1.93, respectively, on a 3-point scale) whereas trait items were somewhat less stereotypical (M = 1.36). However, this pattern was not a function of the particular items selected for the current study, but instead reflected overall differences in the stereotyped views of traits, activities, and appearance characteristics. As Liben and Bigler (2002) reported, the average degree of stereotyping among their entire set of trait items was lower (M = 1.19) than for their activity (M = 1.58) items. Appearance items generally appeared to be stereotyped to a similar degree as the activity items (M = 1.63) (Powlishta et al., 2008).

In addition to matching items on degree of stereotypicality, the average positivity/negativity of the masculine and feminine items were also matched, both between and across domains. This matching was accomplished based on ratings provided by 32 psychology graduate students in a pilot study (using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = “Extremely Negative” to 5 = “Extremely Positive,” with 3 indicating evaluative neutrality). The average positivity/negativity rating of selected items (M = 3.25) did not differ significantly by gender role or domain.

To reflect the targets’ sexual orientation, a statement mentioning the targets’ boyfriend or girlfriend was included to represent the gay and heterosexual conditions. Finally, identical gender-neutral information was added for all targets to increase the realism of the task. This information included demographic characteristics (year in school, hometown) and mention of a summer job, from Liben and Bigler’s (2002) set of gender-neutral occupations. Examples of the resulting vignettes can be found in the Appendix.Footnote 1

Target Evaluation Questions

Each participant rated the target in the given vignette on a set of six questions. These questions assessed how much they thought they would like the target, to what extent would they avoid hanging-out with the target outside of the experiment, how boring they thought the target was, how intelligent they thought the target was, how much they would like to work on the proposed problem-solving task with the target, and how psychologically well-adjusted they thought the target was. Likeability, boring, and intelligence questions were chosen based on past gender-related research which utilized similar items (e.g., Blashill & Powlishta, 2009b; Powlishta, 1995). The “work with” question was necessary for the purposes of maintaining the cover story (that ratings would be used to select partners for a subsequent task). Furthermore, the negatively valenced item “avoid” was chosen, in addition to “boring,” to balance positively worded items (“like,” “intelligent,” “work with”). The last item, which reflects attitudes regarding mental health of targets, was used to assess global impressions of adjustment. In regard to all evaluation questions, we attempted to select questions that were gender-neutral in nature (specifically, boring and intelligent have been rated as gender-neutral in previous research; see Blashill & Powlishta, 2009b). Questions were presented in the order indicated above, and responses were rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 7, with 1 representing “not at all” and 7 representing “very much” (see Appendix).

Manipulation Check

In order to verify that the manipulations were noticed and/or remembered by participants, several questions about the vignettes were presented. First, participants were asked to select the activities, traits, appearance, and mentioned relationship of the given target from a list of all characteristics (presented in a fixed random order) used in all vignettes. From the items selected, six composite scores were created, one for each domain as a function of gender role (i.e., masculine/feminine traits, masculine/feminine activities, and masculine/feminine appearance items). These composite scores reflected the proportion of items in a given gender/domain category (out of 3) endorsed as having been present in the vignette. Whether or not the participant selected items mentioning the target’s specific relationship (“boyfriend’s name is Mike,” “girlfriend’s name is Michelle”) from the same list of characteristics was used to assess the effectiveness of the sexual orientation manipulation. Participants also rated targets’ gender role orientation based on an author-created measure of masculinity/femininity in which participants indicated on a 7-point scale the gender role typicality of their target. Points on the scale were labeled as follows: 1 = “Feminine Only,” 2 = Feminine Mostly,” 3 = “Feminine More,” 4 = “Feminine/Masculine Equally,” 5 = “Masculine More,” 6 = “Masculine Mostly,” 7 = “Masculine Only.” For the final manipulation check item, participants rated targets’ sexual orientation based on an adaptation of the Klein Sexual Orientation Grid (KSOG) (Klein, Sepekoff, & Wolf, 1985), in which participants indicated on a 7-point scale what they believed the orientation of the target to be. Points on the scale were labeled as follows: 1 = “Heterosexual Only,” 2 = “Heterosexual Mostly,” 3 = “Heterosexual More,” 4 = “Hetero/Homo Equally,” 5 = “Homosexual More,” 6 = “Homosexual Mostly,” 7 = “Homosexual Only.”

Demographic Items

Each participant completed a brief demographic form in which they indicated their age, year in school, sex, and race.

Sexual Orientation

Each participant completed a portion of the KSOG to assess sexual orientation. For the purpose of this study, only the variable of Present Self-Identification was used. Participants rated their present self-identification (with respect to sexual orientation) on a 7-point scale, ranging from “heterosexual only” to “homosexual only” (Klein et al., 1985). Intermediate labels on the scale were identical to those described above for the target sexual orientation manipulation check item.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Initially, the data were assessed for univariate and multivariate outliers. Although no univariate outliers were detected, several multivariate outliers were. Seven cases were eliminated based on Mahalnobis d greater than the critical value of 22.45 (p = .0001).

Preliminary analyses were conducted examining relations between demographic characteristics (age, year in school, participant sexual orientation, and ethnicity) and dependent variables. Findings revealed no significant relation between these variables; thus, demographic characteristics (other than participant sex) were not included in subsequent analyses.

Manipulation Check Items

Several manipulation check items were utilized to assess memory for masculine, feminine, and sexual orientation characteristics (by domain) presented in the vignettes. Results from these supplemental analyses revealed that, generally, participants accurately retained key information presented in the vignettes. These findings suggest that the manipulations of gender role and sexual orientation were successful.Footnote 2

Tests of Main Hypotheses

To test the main hypotheses of the study, concerning whether evaluations of targets were influenced by sex of rater, sex of target, sexual orientation of target, target gender role, and domain, a 2 (Sex of Rater) × 2 (Sex of Target) × 2 (Sexual Orientation of Target: Gay, Heterosexual) × 2 (Gender Role: Typical, Atypical) × 3 (Domain: Activities, Traits, Appearance) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed on six dependent measures (i.e., reflecting the six target evaluation ratings) (see Table 1). There were several significant interactions found, including Sex of Rater by Sex of Target, F(6, 252) = 2.25, p = .05, η² = .04 (accounting for 4 % of the variance), Target Gender Role by Domain, F(12, 504) = 1.95, p = .03, η² = .04 (accounting for 4 % of the variance), and Sex of Rater by Sex of Target by Sexual Orientation of Target, F(6, 252) = 3.16, p = .001, η² = .07 (accounting for 7 % of the variance). To follow-up these multivariate effects, ANOVAs were conducted on each of the six dependent variable, as described below.

Sex of Rater by Sex of Target

Univariate ANOVAs revealed a significant Sex of Rater by Sex of Target interaction on one dependent variable, “Like,” F(1, 257) = 4.43, p = .04, η² = .02 (accounting for 2 % of the variance). To follow-up this significant interaction, simple main effect tests were conducted examining the effect of Sex of Rater at each level of Sex of Target. This yielded a significant difference for male targets, F(1, 301) = 7.82, p = .001. Female participants rated male targets as more likable than male participants (see Table 2). There was no significant sex difference in ratings of female targets.

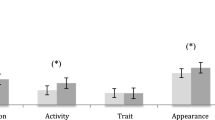

Target Gender Role by Domain

Results indicated a significant Target Gender Role by Domain interaction on two dependent variables, “Like,” F(2, 257) = 5.42, p = .01, η² = .04 (accounting for 4 % of the variance), and “How intelligent do you think the target is?” (IQ), F(2, 257) = 3.00, p = .05, η² = .02 (accounting for 2 % of the variance). Simple main effect tests examining the effect of Target Gender Role at each level of Domain indicated that, for “Like,” significant differences were found between the rating of gender typical and atypical targets for the activity, F(1, 304) = 5.05, p = .03, and appearance, F(1, 304) = 9.18, p = .003, domains. These results indicated that participants viewed targets who were gender atypical in terms of their activities or appearance as less likable than gender typical targets, thus partially confirming hypothesis 3 (see Table 3). No significant differences were found between typical and atypical targets described using trait items on rating of likeability. None of the simple main effects were significant for the “IQ” measure (see Table 4).

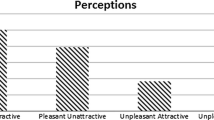

Sex of Rater by Sex of Target by Sexual Orientation of Target

Finally, the follow-up univariate ANOVA revealed a significant Sex of Rater by Sex of Target by Sexual Orientation of Target interaction for one dependent variable, “How much would you like to work on the problem-solving task with the target?” (Work With), F(1, 257) = 12.38, p = .0001, η² = .05 (accounting for 5 % of the variance). To follow-up this significant three-way interaction, the two-way interaction between Sex of Target and Sexual Orientation of Target was investigated within each level of Sex of Rater. Results indicated that this interaction was only significant for male participants, F(1, 304) = 9.42, p = .001. To further explore this interaction, the simple main effect of Sex of Target was investigated at each level of Sexual Orientation of Target for male participants. This effect was significant for gay targets only, F(1, 304) = 11.50, p = .0001, indicating that male participants wished to work with lesbian targets more so than gay male targets, thus confirming hypothesis 4. Alternatively, the simple main effect of Sexual Orientation of Target was examined separately for each Sex of Target, again for male participants. Results indicated that this interaction was only significant for male targets, F(1, 304) = 6.01, p = .02 (see Table 5). This finding indicated that male participants wished to work with heterosexual male targets more so than gay male targets.Footnote 3

Discussion

The present study examined the effect of five variables (Sex of Rater, Sex of Target, Sexual Orientation of Target, Target Gender Role, and Domain) on six measures of target evaluation. To our knowledge, this analogue study was the first to evaluate all of these variables simultaneously. The following hypotheses were proposed: (1) gender atypical targets would be viewed more negatively (relative to typical targets) when the target is male; (2) male participants would view gender atypical targets (relative to gender typical targets) more negatively than female participants; (3) gender atypical targets would be viewed more negatively (relative to gender typical targets) in the appearance domain than in other domains; and (4) male participants may view gay male targets more negatively than gay female targets. Results from multivariate analyses supported Hypothesis 4, and partially supported Hypothesis 3.

Regarding Hypothesis 4, results revealed that male participants wished to work with lesbian and heterosexual male targets more so than gay male targets. These findings were consistent with past research that has found gay male targets to be viewed more negatively than lesbians and heterosexual male targets (e.g., Herek, 1988; Kerns & Fine, 1994; Kite & Whitley, 1998) when rated by heterosexual male participants. Additionally, this finding also echoes past work, in that males hold more negative attitudes regarding homosexuality as compared to females (e.g., Herek, 1988, Studies 2 and 3, 2000; Herek & Capitanio, 1999; Ratcliff et al., 2006, Whitley, 2001). These results held even after controlling for presented and perceived gender role characteristics.

Theorists have suggested that one can account for anti-gay attitudes, particularly by and toward males, by gender belief systems (Kite & Whitley, 1998). Gender belief systems are stereotypes held regarding men and women, as well as attitudes toward gender role norms and those who violate them, with males typically adhering to this system more rigidly than females. Due to research that indicates individuals perceive gay men and lesbians to be gender atypical (Blashill & Powlishta, 2009a; Kite & Deaux, 1987), it is argued that the reason why heterosexual males view gay men particularly negatively is because it is assumed they are gender atypical. However, the results from the current study did not necessarily support the gender belief system hypothesis. Because the significant Sex of Rater by Sex of Target by Sexual Orientation of Target interaction collapsed across the targets’ gender role, it can be seen that male participants were reacting negatively to gay male targets independently from gender atypicality. Thus, although gender atypicality may serve as part of males’ negative reaction to gay targets (and in particular gay male targets), it does not account for this finding entirely, suggesting that being gay, in and of itself, is negatively viewed, especially by male participants.

Results also partially supported Hypothesis 3, revealing that participants viewed targets with gender atypical activities and appearance items as being less likable than targets with gender typical activities and appearance items. Gender typicality did not influence ratings in the trait domain, however. Given past findings in this area, perhaps this pattern was not surprising. Horn (2007) found that male and female participants rated appearance gender role violations as the least desirable. This was found collapsed across target sexual orientation and sex. It seems that visible gender role violations (i.e., appearance and activity) seem to be more negatively viewed than gender role violations that are not inherently observable (i.e., traits). This interpretation is further strengthened given that trait gender stereotypes are the least extreme in comparison to other domains of gender roles (i.e., occupations and activities) (Liben & Bigler, 2002), suggesting that it is viewed as more common for males and females to share various personality traits than it is for them to share activities or occupational interests.

One strength of the current study was that the effects of the study variables held even when various individual differences variables were controlled for (see footnote 2). This finding attests to the strong impact that target gender role and sexual orientation have on attitudes. Despite the different types of individuals in the study (e.g., those with low and high levels of anti-gay prejudice, traditional gender role attitudes, or personal masculinity and femininity), their responses to individual targets varied as a function of target characteristics (gender role, sexual orientation), regardless of these individual difference characteristics. This specific finding is in opposition to one previous study (Lehavot & Lambert, 2007) which found that negative reactions toward gay targets were only seen in participants who endorsed high levels of anti-gay attitudes. These divergent results may be related to sample compositions. For example, the Lehavot and Lambert study was conducted at a “relatively liberal university” whereas the current study was conducted at a Jesuit university—which typically would not be described as “liberal,” at least with respect to issues of gender and sexual orientation. Thus, the setting of the current study may have reflected more negative attitudes generally about homosexuality.

Limitations

Despite the additions to the literature that the current study provided, it is not without limitations. Namely, the sample consisted of undergraduate students from a private, Midwestern, Jesuit institution. Thus, generalizations to non-college educated individuals, or those who are older than the typical 18–22 year olds involved in this study, should be done with caution. Indeed, education level tends to be negatively correlated with sexual prejudice (Herek, 1994). Similarly, because the sample was largely White, and Black American college students possess more negative attitudes towards gay men and lesbians compared to their White counterparts (e.g., Whitley, Childs, & Collins, 2011), the findings may not translate to ethnic minority individuals. Further, although we sampled participants from a Catholic institution, we did not assess participants’ religion; thus, although the majority of participants are likely to be Catholic, the specific religious make-up of the sample is unknown. Prior research has demonstrated that religious affiliation impacts attitudes toward homosexuality (Finlay & Walther, 2003; Herek, 1984; Wills & Crawford, 2000); however, Catholics do not typically hold the most prejudiced (nor the least prejudiced) views toward homosexuality (Finlay & Walther, 2003). Thus, the findings from the current study may yield even larger effects with a sample that includes non-college educated individuals, as well as participants who belong to varied religions. Additionally, the assessment of raters’ sexual orientation was limited to present self-identification. Although we were not anticipating having a large enough sample of sexual minority raters to conduct analyses on, it is possible that if a multifaceted approach to measuring sexual orientation (e.g., behaviors, fantasy, emotions, identity) was employed, varying results would have been revealed.

Future Research

Regarding future research, perhaps efforts to assess not only evaluative items, such as those used in the current study, but also variables which pertain to employment discrimination, social rejection, aggression and violence would be important in understanding whether the effects demonstrated in the current study also relate to other behavioral responses. Regarding aggression, past work (Parrott & Zeichner, 2005, 2008) has found heterosexual male participants to respond to gay targets with more aggression (through an aggression paradigm) than to heterosexual targets. This research demonstrated that not only are gay men disliked more so than heterosexual men, but that they were also more likely to be responded to with aggression. A notable gap in the aggression literature is that, to date, no studies have included gender role of target as an independent variable; thus, it is unknown if male participants would respond equally aggressively to feminine men (controlling for sexual orientation) as they do toward gay men. Researchers may also be interested in including female participants and targets within this methodology. Future research may also wish to examine these effects via alternative mediums. For example, the current study, and past research (Blashill & Powlishta, 2009b) have found these effects to hold when presenting stimuli through written vignettes, but more research is needed to assess whether these findings hold true with targets presented in videos or perhaps even with actors in vivo.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the current study investigated possible sources of sexual prejudice directed at gay men and lesbians. Specifically, sex of rater, as well as target sex, sexual orientation, gender role, and domain of gender role attributes were examined as factors associated with evaluations of targets. Previous research simultaneously examining gender role and sexual orientation is scant, and the current study added the novel aspect of gender role domain—a recently noted salient variable in attitudes toward gender role violations. Results revealed that male participants, in particular, viewed gay male targets as being less desirable to work with than lesbian and heterosexual male targets. Gender atypical targets described in terms of activities or appearance were viewed more negatively than their gender typical counterparts whereas when targets were described using trait terms there were no significant differences noted between gender typical and atypical targets.

In sum, these results highlight the role gender atypicality plays in sexual prejudice. Specifically, it seems that observable gender role violations (e.g., activities and appearance) are more negatively appraised than violations that are non-observable (e.g., personality traits), and because gay individuals are assumed to be gender atypical (Blashill & Powlishta, 2009a; Kite & Deaux, 1987), part of individuals’ negative reaction to gay males and lesbians may be driven by overt violations of traditional gender roles. However, the results from this study also show that there is something beyond mere gender role violations that leads to negative evaluations of gay men and lesbians; that is, participants still responded negatively to gay targets holding constant gender role, suggesting that being gay in and of itself is considered undesirable. Conversely, it is often assumed that the driving force behind negative reactions to gender role violations is due to assumptions of homosexuality; however, the results from the current study indicated that gender role violations were still viewed negatively when controlling for sexuality. This pattern suggests that individuals are reacting to something above and beyond simple assumptions about homosexuality. In other words, being gay and violating traditional gender roles each make independent contributions to negative evaluations received from others. Thus, it is crucial that the intersectionality of sex, gender role, gender role domain, and sexual orientation are explored in regard to the study of sexual prejudice.

Notes

The full set of vignettes is available from the corresponding author.

More detailed information regarding the manipulation check analyses are available from the corresponding author.

Individual difference variables (i.e., attitudes toward gay men and lesbians, attitudes toward feminine men and masculine women, participant’s own gender-role orientation, and social desirability response biases) were also collected and examined via hierarchical multiple regression. Results indicated that none of these variables interacted with the study variables, indicating that the effects of the manipulated variables in the current study held, even when controlling for various individual difference variables. Because none of these interactions was significant, the results are not presented here in detail. However, further information is available from the corresponding author.

References

Blashill, A. J., & Powlishta, K. K. (2009a). Gay stereotypes: The use of sexual orientation as a cue for gender-related attributes. Sex Roles, 61, 783–793.

Blashill, A. J., & Powlishta, K. K. (2009b). The impact of sexual orientation and gender role on evaluations of men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 10, 160–173.

Boysen, G. A., Vogel, D. L., Madon, S., & Wester, S. R. (2006). Mental health stereotypes about gay men. Sex Roles, 54, 69–82.

David, B., Grace, D., & Ryan, M. K. (2004). The gender wars: A self-categorization perspective on the development of gender identity. In M. Bennett & F. Sani (Eds.), The development of the social self (pp. 138–158). New York: Psychology Press.

Finlay, B., & Walther, C. S. (2003). The relation of religious affiliation, service attendance, and other factors to homophobic attitudes among university students. Review of Religious Research, 44, 370–393.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., McLaughlin, K. A., Keyes, K. M., & Hasin, D. S. (2010). The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 452–459.

Herek, G. M. (1984). Beyond “homophobia”: A social psychological perspective on attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 10, 1–21.

Herek, G. M. (1988). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: Correlates and gender differences. Journal of Sex Research, 25, 451–477.

Herek, G. M. (1994). Assessing attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: A review of empirical research with the ATLG scale. In B. Greene & G. M. Herek (Eds.), Lesbian and gay psychology (pp. 206–228). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Herek, G. M. (2000). The psychology of sexual prejudice. Current Directions in Psychology Science, 9, 19–22.

Herek, G. M. (2009). Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 54–74.

Herek, G. M., & Capitanio, J. P. (1999). Sex differences in how heterosexuals think about lesbians and gay men: Evidence from survey context effects. Journal of Sex Research, 36, 348–360.

Herek, G. M., & Garnets, L. D. (2007). Sexual orientation and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 353–375.

Horn, S. S. (2007). Adolescents’ acceptance of same-sex peers based on sexual orientation and gender expression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 363–371.

Kerns, J. G., & Fine, M. A. (1994). The relation between gender and negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbians: Do gender role attitudes mediate this relation? Sex Roles, 31, 297–307.

Kite, M. E., & Deaux, K. (1987). Gender belief systems: Homosexuality and the implicit inversion theory. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11, 83–96.

Kite, M. E., & Whitley, B. E. (1998). Do heterosexual women and men differ in their attitudes toward homosexuality? A conceptual and methodological analysis. In G. M. Herek (Ed.), Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals (pp. 108–137). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Klein, F., Sepekoff, B., & Wolf, T. J. (1985). Sexual orientation: A multi-variable dynamic process. Journal of Homosexuality, 11, 35–49.

Lehavot, K., & Lambert, A. J. (2007). Toward a greater understanding of antigay prejudice: On the role of sexual orientation and gender role violation. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29, 279–292.

Levy, G. D., Taylor, M. G., & Gelman, S. A. (1995). Traditional and evaluative aspects of flexibility in gender roles, social conventions, moral rules, and physical laws. Child Development, 66, 515–531.

Liben, L. S., & Bigler, R. S. (2002). The developmental course of gender differentiation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 67(2, Serial No. 269).

Lippa, R. A. (2005). Sexual orientation and personality. Annual Review of Sex Research, 16, 119–153.

Madon, S. (1997). What do people believe about gay males? A study of stereotype content and strength. Sex Roles, 37, 663–685.

Mays, V. M., & Cochran, S. D. (2001). Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbians, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1869–1876.

McCreary, D. R. (1994). The male role and avoiding femininity. Sex Roles, 31, 517–531.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697.

Parrott, D. J., & Zeichner, A. (2005). Effects of sexual prejudice and anger on physical aggression toward gay and heterosexual men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 6, 3–17.

Parrott, D. J., & Zeichner, A. (2008). Determinants of anger and physical aggression based on sexual orientation: An experimental examination of hypermasculinity and exposure to male gender role violations. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 891–901.

Powlishta, K. K. (1995). Intergroup processes in childhood: Social categorization and sex role development. Developmental Psychology, 31, 781–788.

Powlishta, K. K. (2004). Gender as a social category: Intergroup processes and gender-role development. In M. Bennett & F. Sani (Eds.), The development of the social self (pp. 103–134). New York: Psychology Press.

Powlishta, K., Watterson, E., Blashill, A., & Kinnucan, C. (2008, April). Physical or appearance-related gender stereotypes. Poster presented at the Gender Development Research Conference, San Francisco, CA.

Ratcliff, J. J., Lassiter, G. D., Markman, K. D., & Snyder, C. J. (2006). Gender differences in attitudes toward gay men and lesbians: The role of motivation to respond without prejudice. Personality and Social Psychological Bulletin, 32, 1325–1338.

Rothman, E. F., Exner, D., & Baughman, A. L. (2011). The prevalence of sexual assault against people who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual in the United Stated: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 12, 55–66.

Schope, R. D., & Eliason, M. J. (2004). Sissies and tomboys: Gender role behaviors and homophobia. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 16, 73–97.

Sirin, S. R., McCreary, D. R., & Mahalik, J. R. (2004). Differential reactions to men and women’s gender role transgressions: Perceptions of social status, sexual orientation, and value dissimilarity. Journal of Men’s Studies, 12, 119–132.

Taylor, A. (1983). Conceptions of masculinity and femininity as a basis for stereotypes of male and female homosexuals. Journal of Homosexuality, 9, 37–53.

Watterson, E. S., & Powlishta, K. K. (2007, March). Children’s evaluative reactions to gender stereotype violations. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Boston, MA.

Whitley, B. E. (2001). Gender-role variables and attitudes toward homosexuality. Sex Roles, 45, 691–721.

Whitley, B. E., Childs, C. E., & Collins, J. B. (2011). Differences in black and white American college students’ attitudes towards lesbians and gay men. Sex Roles, 64, 299–310.

Wills, G., & Crawford, R. (2000). Attitudes toward homosexuality in Shreveport-Bossier City, Louisiana. Journal of Homosexuality, 38, 97–116.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Target Vignettes

Appendix: Target Vignettes

Heterosexual Male, Masculine Activities

“John is a sophomore at _________ University who grew-up in a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. He has been dating his girlfriend Michelle since the middle of his freshman year. To save money for school, this past summer John worked as a cook in a restaurant. John enjoys fishing, building with tools, and fixing cars in his spare time.”

Gay Male, Masculine Activities

“John is a sophomore at _________ University who grew-up in a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. He has been dating his boyfriend Mike since the middle of his freshman year. To save money for school, this past summer John worked as a cook in a restaurant. John enjoys fishing, building with tools, and fixing cars in his spare time.”

Heterosexual Female, Masculine Activities

“Stephanie is a sophomore at _________ University who grew-up in a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. She has been dating her boyfriend Mike since the middle of her freshman year. To save money for school, this past summer Stephanie worked as a cook in a restaurant. Stephanie enjoys fishing, building with tools, and fixing cars in her spare time.”

Gay Female, Masculine Activities

“Stephanie is a sophomore at _________ University who grew-up in a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. She has been dating her girlfriend Michelle since the middle of her freshman year. To save money for school, this past summer Stephanie worked as a cook in a restaurant. Stephanie enjoys fishing, building with tools, and fixing cars in her spare time.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blashill, A.J., Powlishta, K.K. Effects of Gender-Related Domain Violations and Sexual Orientation on Perceptions of Male and Female Targets: An Analogue Study. Arch Sex Behav 41, 1293–1302 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9971-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9971-1