Abstract

Sexual dysfunctions and difficulties are common experiences that may impact importantly on the perceived quality of life, but prevalence estimates are highly sensitive to the definitions used. We used questionnaire data for 4415 sexually active Danes aged 16–95 years who participated in a national health and morbidity survey in 2005 to estimate the prevalence of sexual dysfunctions and difficulties and to identify associated sociodemographic factors. Overall, 11% (95% CI, 10–13%) of men and 11% (10–13%) of women reported at least one sexual dysfunction (i.e., a frequent sexual difficulty that was perceived as a problem) in the last year, while another 68% (66–70%) of men and 69% (67–71%) of women reported infrequent or less severe sexual difficulties. Estimated overall frequencies of sexual dysfunctions among men were: premature ejaculation (7%), erectile dysfunction (5%), anorgasmia (2%), and dyspareunia (0.1%); among women: lubrication insufficiency (7%), anorgasmia (6%), dyspareunia (3%), and vaginismus (0.4%). Highest frequencies of sexual dysfunction were seen in men above age 60 years and women below age 30 years or above age 50 years. In logistic regression analysis, indicators of economic hardship in the family were positively associated with sexual dysfunctions, notably among women. In conclusion, while a majority of sexually active adults in Denmark experience sexual difficulties with their partner once in a while, approximately one in nine suffer from frequent sexual difficulties that constitute a threat to their well-being. Sexual dysfunctions seem to be more common among persons who experience economic hardship in the family.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sexual dysfunctions and difficulties are commonly encountered experiences that impact on the quality of life for adult populations around the world (Laumann, Paik, & Rosen, 1999; Lewis et al., 2004; Ventegodt, 1998). Recent epidemiologic data indicate that, at a given time, around 20–30% of men and 40–45% of women report at least one sexual dysfunction (Lewis et al., 2004; Nazareth, Boynton, & King, 2003). However, numerous setting- and study-specific factors may affect prevalence estimates and thereby make comparisons between studies and countries difficult.

Denmark is a small Scandinavian welfare society with 5.4 million inhabitants, a high gross domestic product per capita, and relatively liberal public attitudes toward sexual matters (Graugaard et al., 2004). Lately, studies have shown associations between low socioeconomic position and measures of poor health and increased mortality (Dalton et al., 2008; The Danish Ministry of Health, 2000), but it is not clear whether this social inequality in health also applies to sexual health. In other countries around the world, studies have found associations between sexual dysfunction and indicators of low socioeconomic status such as low education (Ahn et al., 2007; Nicolosi, Glasser, Moreira, & Villa, 2003a) and low household income (Ahn et al., 2007), while others did not confirm such associations (Chew, Stuckey, Bremner, Earle, & Jamrozik, 2008; Öberg, Fugl-Meyer, & Fugl-Meyer, 2004; Richters, Grulich, de Visser, Smith, & Rissel, 2003). Rather consistently, however, several studies have reported an association between unmarried status and increased prevalence of sexual dysfunctions (Chew et al., 2008; Laumann et al., 1999; Mercer et al., 2005; Moreira, Lisboa Lobo, Villa, Nicolosi, & Glaser, 2002).

The aim of this population-based epidemiologic study was to provide updated prevalence estimates for sexual dysfunctions and sexual difficulties in Denmark and to identify sociodemographic factors associated with clinically relevant sexual dysfunctions.

Method

Participants

The Danish Health and Morbidity Program is a comprehensive series of nationally representative interview surveys conducted in 1986–1987, 1991, 1994, 2000 and, most recently, in 2005 (Rasmussen & Kjøller, 2004). The surveys were based on samples of Danes aged 16 years or older, drawn randomly by their personal identification number in the Danish Civil Registration System (Pedersen, Gøtzsche, Møller, & Mortensen, 2006). Each identified person received a letter of invitation with information about the study. Upon consent, participants, who received no compensation for their participation in the study, underwent a structured personal interview at home conducted by a professional interviewer. Interview questionnaires covered matters related to health, morbidity, life style, and sociodemographic background, including place of residence, education, employment, income, and family status.

In 2005, a total of 10,916 individuals were invited to take part in the new round of the study. In this round, the personal interview was followed by completion of a self-administered questionnaire which covered a series of sensitive issues, including questions about sexual activity and sexual difficulties experienced with a partner in the last 12 months.

Measures

As shown in Appendix 1, men were asked questions about erectile difficulties, anorgasmia (i.e., delayed orgasm or inability to reach climax), premature ejaculation, and dyspareunia (i.e., genital pain in relation to intercourse), and women were asked about lubrication insufficiency, anorgasmia, dyspareunia, and vaginismus (i.e., vaginal cramps that precluded penetration) during sexual activity with a partner in the last year. The extent to which each sexual difficulty had been present was measured on a five-level Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “every time.” Furthermore, participants were asked to indicate whether they perceived their sexual difficulties as a problem. To capture all men with erectile difficulties we used the most troubled answer to the two original questions about erectile difficulties in all statistical analysis. For example, a man was categorized as having erectile difficulties “sometimes” if he reported that he had “not at all” experienced that his erections were not strong enough for penetration, but that his erections “sometimes” disappeared soon after penetration.

According to the DSM-IV-TR, a sexual difficulty has to be recurrent and persistent and cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty in order to be considered a clinically relevant sexual dysfunction (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Most participants who reported sexual difficulties in our study, however, did not qualify as having a genuine sexual dysfunction. To have a sexual dysfunction we required that a given sexual difficulty be both frequent (i.e., experienced “often” or “every time”) and perceived as a problem. Consequently, throughout this paper, we distinguished between persons with “sexual dysfunctions” and those with infrequent or mild “sexual difficulties” with the latter group consisting of all participants who reported having sexual difficulties “rarely” or “sometimes” regardless of whether these difficulties were considered problematic or not as well as participants who reported having sexual difficulties “often” or “every time” but who did not consider them to be problematic.

Statistical Analysis

To identify possible socioeconomic correlates of sexual dysfunctions we performed polytomous logistic regression analyses using the SAS procedure PROC LOGISTIC (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for measures of urbanicity (place of residence), education level (years of school attendance and level of post-secondary education), current employment status, household economy (household income and difficulties paying bills in the last year), and marital status.

Specifically, in each analysis we used a trisection of the relevant sexual difficulty to delineate (1) those without the sexual difficulty, (2) those with infrequent or mild sexual difficulty, and (3) those with sexual dysfunction. To minimize complexity we only presented ORs and 95% CIs for comparisons between those in categories 1 and 3. However, due to small numbers of men reporting dyspareunia and of women reporting vaginismus, in the calculation of ORs for these outcomes we compared individuals in category 1 with the combined group of participants in categories 2 and 3.

In all analyses, we adjusted for age by using cubic splines restricted to be linear in the tail (Harrell, 2001). We also examined the impact of adjusting the ORs for possible confounding by tobacco smoking, frequency of alcohol intake during the last year, and body mass index. However, only in few situations did such additional adjustment result in a change in the OR by more than 15%, so all reported ORs were adjusted only for age.

In a robustness analysis, we explored the stability of our results by repeating our analyses for sexual dysfunction overall using a different cut-point to capture participants with sexual dysfunction. As in the main analysis, to be regarded as having a sexual dysfunction, participants had to report at least one sexual difficulty as occurring “often” or “every time,” but this time we disregarded whether the difficulty was considered a problem or not.

Throughout, two-sided p-values < .05 obtained in Wald tests and 95% CIs that excluded unity were considered indicators of statistical significance. To get stable ORs, we chose as reference those categories of the sociodemographic variables that were most common in the combined group of men and women.

The study was approved by the Danish data protection agency (approval no. 2007-41-0022).

Results

Participation Rate

Of the 10,916 invited persons (5395 men and 5521 women), a total of 7275 persons underwent a personal interview, and of these, 5552 persons or 76% (2573 men, 2979 women) returned the questionnaire, yielding overall participation rates of 48% for men and 54% for women. A total of 2120 (82%) men and 2295 (77%) women who had been sexually active with a partner in the last year were included in the present study. Sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunctions and Difficulties

The overall proportion of adult Danes who had experienced at least one sexual dysfunction in the last year was 11% (95% CI: 10–13%) in both men and women (Table 2). The proportion of participants who had experienced sexual difficulties at least “rarely” in the last year but did not meet our criteria for having a sexual dysfunction was also similar in men (68%, 95% CI: 66–70%) and women (69%, 95% CI: 67–71%). When combined, the overall proportion of sexually active Danes who had experienced sexual dysfunctions or difficulties in the last year was 79% (95% CI: 78–81%) for men and 80% (95% CI: 78–82%) for women.

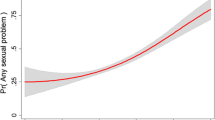

As shown in Fig. 1, the proportion of men below age 20 years who had any sexual dysfunction was low (2%). Among men aged 20–59 years the average proportion was 10%, whereas 20% of men aged 60 years or more had at least one sexual dysfunction. The prevalence of sexual difficulties was high in all age groups.

In women, the overall prevalence of sexual dysfunction was higher among women below age 30 years (21%) and those above age 50 years (10%) than in women in their 30s and 40s (7%). The prevalence of sexual difficulties was high in all age groups, being 60% in women below age 20 years, 68% in the 20–49 year olds, and 72% in women aged 50 years or older. In both sexes, age-specific patterns differed considerably among the individual sexual dysfunctions and difficulties (Fig. 1).

Specific Sexual Dysfunctions and Difficulties, Men

Overall, erectile difficulties meeting our criteria for being a sexual dysfunction were reported by 5% of men (Table 2), being rare (1%) before age 50 years, after which age it increased to 5% in 50–59 year-olds and 16% in men aged 60 years or older. Erectile difficulties exhibited a J-shaped curve, with lowest prevalence (18%) reported by men aged 30–39 years and highest prevalence (66%) in those aged 70 years or older (Fig. 1).

Anorgasmia rarely constituted a sexual dysfunction in men (2%) (Table 2). However, the age-specific prevalence of anorgasmia as a sexual difficulty was parallel to the J-shaped curve for erectile difficulties, with the lowest prevalence among men in their 20s and 30s (23%), increasing gradually to 65% in the 70+ year-olds (Fig. 1).

Premature ejaculation was the most frequently reported sexual dysfunction affecting 7% of men, and another 54% had experienced premature ejaculation as a sexual difficulty in the last year (Table 2). Unlike for erectile dysfunction and anorgasmia, the prevalence of premature ejaculation, whether as a sexual dysfunction or sexual difficulty, exhibited only minor variation by age (Fig. 1).

Dyspareunia was an exceedingly rare sexual dysfunction among men in our study (0.1%) (Table 2). Dyspareunia as a sexual difficulty was reported by 18% of the youngest men below age 20 years, but by only 3% of 70+ year-old men.

Specific Sexual Dysfunctions and Difficulties, Women

Lubrication insufficiency was a sexual dysfunction reported by 7% of women, and other 50% reported lubrication insufficiency as a sexual difficulty (Table 2). Lubrication insufficiency was most frequent among women aged 16–29 years and those older than 50 years (Fig. 1).

Anorgasmia was reported by 6% as a sexual dysfunction, and experienced by other 63% as a sexual difficulty (Table 2). Women under age 30 years had a markedly higher prevalence of anorgasmia as a sexual dysfunction (15%) than women aged 30 years or older (4%) (Fig. 1).

Dyspareunia was a sexual dysfunction reported by 3% of women and experienced as a sexual difficulty by other 25% (Table 2). Dyspareunia was most frequent among women below age 30 years (Fig. 1).

Vaginismus was reported by 0.4% of women as a sexual dysfunction, being most common among the youngest women in age groups 16–19 years (3%) and 20–29 years (1%) (Fig. 1). Other 4% of women reported vaginismus as a sexual difficulty (Table 2).

Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Sexual Dysfunctions

We identified a number of sociodemographic variables that were significantly associated with sexual dysfunctions in men (Table 3) and women (Table 4).

Men

Except for a positive association with difficulties paying bills last year (OR = 2.72; 95% CI: 1.44–5.14) the overall prevalence of sexual dysfunction in men varied little between participants with different socioeconomic backgrounds (Table 3).

Place of Residence

There was no statistically significant association between place of residence and any of the four studied sexual dysfunctions in men.

Education

Men reporting ≥12 years of school attendance reported premature ejaculation as a sexual dysfunction less frequently than those with fewer years of basic schooling (p-trend = .007). None of the other sexual dysfunctions differed significantly among men with different levels of school attendance or post-secondary education.

Employment

Current unemployment was associated with a more than threefold increased risk of erectile dysfunction (OR = 3.11; 95% CI: 1.45–6.67).

Economy

As mentioned, difficulties paying bills last year were associated with significantly increased rates of sexual dysfunction overall, a pattern that applied to premature ejaculation (OR = 3.01, 95% CI: 1.63–5.56) and, almost significantly so, to erectile dysfunction (OR = 2.88, 95% CI: 0.95–8.79) and to dyspareunia (OR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.00–2.86). Men with an annual household income below 200,000 Danish Kroner (approximately US$ 40,000) reported dyspareunia significantly more often than men with higher incomes (p-trend = .003).

Marital Status

Unmarried men were more likely to report anorgasmia (OR = 3.06; 95% CI: 1.03–9.10), but they reported premature ejaculation less frequently (OR = 0.51; 95% CI: 0.28–0.96) than married men.

Women

The overall prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women varied significantly across strata of place of residence, years of school attendance, post-secondary education, household income, and difficulties paying bills last year (Table 4).

Place of Residence

Generally, women living in the capital area (Copenhagen) or cities with ≥100,000 inhabitants were more likely to report each of the studied sexual dysfunctions than women living in areas with <10,000 inhabitants, a pattern that reached statistical significance for anorgasmia (p = .007) and for sexual dysfunction overall (p < .001).

Education

Women with ≥12 years of school attendance (p-trend = .04) and those with high further education (p = .047) more often reported sexual dysfunction overall than women with low education. These associations almost reached statistical significance for anorgasmia (p-trend = .07 for years of school attendance) and lubrication insufficiency (p = .06 for post-secondary education).

Employment

Female sexual dysfunctions did not vary significantly according to employment status.

Economy

There were statistically significant positive associations between measures of economic hardship in the family and the prevalence of sexual dysfunctions. The overall sexual dysfunction prevalence was more than twice as high in women with a household income <200,000 Danish Kroner per year compared with women with a household income of 400,000–599,999 Danish Kroner per year (22% vs. 9%, p-trend = .02), and twice as high among women with difficulties paying their bills compared with women without such difficulties (20% vs. 10%, p = .006). At least one measure of economic hardship was significantly associated with each of the four studied female sexual dysfunctions.

Marital Status

Like the situation for unmarried men, unmarried women more frequently reported anorgasmia as a sexual dysfunction than did married women (OR = 2.13; 95% CI: 1.12–4.03).

In a set of supplementary statistical models, we examined if the above statistically significant associations of female sexual dysfunctions with place of residence, education level, and family economy were mutually confounded by including household income as an extra covariate in the regression models for place of residence and each of the two education variables. All resulting ORs remained virtually unchanged and retained statistical significance. Likewise, ORs for household income remained similar and the trend remained statistically significant when including either of the two education variables in the regression model.

Robustness Analysis

While 11% of both men and women had at least one sexual dysfunction in the main analysis, participants with sexual dysfunction in the robustness analysis were those 17% of men and 23% of women who had experienced at least one of the specific sexual difficulties “often” or “every time,” regardless of whether they perceived their difficulties as a problem or not. For both men and women, associations between the examined socioeconomic variables and sexual dysfunction overall were generally similar to those observed in the main analysis. Indeed, the only noteworthy difference in men was that few years of school attendance became statistically significantly associated with increased risk of sexual dysfunction overall (p-trend = .01). In women, significant positive associations in the main analysis of sexual dysfunction overall with level of post-secondary education and with difficulties paying bills lost statistical significance in the robustness analysis (post-secondary education, p = 0.13; difficulties paying bills, p = .06).

Discussion

Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunctions and Difficulties

Overall, 11% of sexually active men and women in Denmark experience sexual difficulties that are severe enough to be regarded as clinically relevant sexual dysfunctions, while another 68–69% experience infrequent or mild sexual difficulties at least once in a while. These estimates serve to illustrate the considerable variability in calculating prevalence estimates for sexual dysfunctions and underscore the importance of taking the used definitions into account when comparing estimates between studies.

Our finding of similar prevalence estimates for sexual dysfunctions and difficulties in the two sexes are in contrast to several previous reports. Generally, studies have reported higher prevalence estimates of sexual dysfunction in women than men (Fugl-Meyer & Fugl-Meyer, 1999; Laumann et al., 1999; Mercer et al., 2003; Nazareth et al., 2003). Although being sexually active was also an inclusion criterion in some prior studies (Fugl-Meyer & Fugl-Meyer, 1999; Mercer et al., 2003), we noted that of the 5552 persons in our study who returned the questionnaire a somewhat larger proportion of women (23%) than men (18%) were excluded from the analyses because they had not had sex with a partner in the last year. If the higher proportion of excluded, sexually inactive women were sexually inactive due to problems of sexual dysfunction, this could have contributed to the similar prevalence estimates in men and women in our study. Also, in contrast to some previous studies, we did not include low sexual desire or decreased sexual interest among the sexual dysfunctions studied, as these data have been reported by others (Eplov, Giraldi, Davidsen, Garde, & Kamper-Jørgensen, 2007). However, in another study the prevalence of sexual dysfunction was higher in women than men even after lack of interest in sex was excluded from the analysis (Mercer et al., 2003).

The age-specific patterns seen for the individual sexual dysfunctions in men are generally in agreement with the literature. For instance, the marked increase in erectile dysfunction with advancing age has been reported previously (Ahn et al., 2007; Chew et al., 2008; Lyngdorf & Hemmingsen, 2004; Nicolosi et al., 2003a), just as the higher prevalence of orgasm difficulties among the youngest men and men above age 40 years (Richters et al., 2003; Ventegodt, 1998). Age-specific prevalence estimates differed much less for premature ejaculation, possibly reflecting that the perception of what is meant by premature ejaculation may differ among age groups. It has been argued that reported prevalence estimates for premature ejaculation may be particularly difficult to compare between studies (Montorsi, 2005).

All the studied female sexual dysfunctions exhibited a pattern of lower prevalence among women aged 30–49 years than women in younger and older age groups, and the highest prevalence of sexual dysfunction overall was among the youngest age groups (<30 years). This age pattern in women was in contrast to the pattern seen in men, which was dominated by the steady age-related increase in prevalence of erectile dysfunction and anorgasmia and the rather stable prevalence of premature ejaculation across the different age groups. The high prevalence of sexual dysfunctions in the youngest women may reflect that a considerable proportion of young women experience difficulties to thrive sexually in a phase of life that is often characterized by sexual experimentation and unstable partner relations. It is possible that the lower prevalence of sexual difficulties in women aged 30–49 years reflects a combination of more stable partner relations and the use of strategies to deal with sexual difficulties, such as the use of lubricants among women with lubrication insufficiency.

Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Sexual Dysfunction

Our analyses of sociodemographic factors suggest that, even in Denmark where the gap between rich and poor is small compared with the situation in many other developed countries, there may be a social gradient in health that also pertains to sexual health. Considering all the studied sexual dysfunctions together we showed that men and women who experienced difficulties paying their bills were twice as likely to report sexual dysfunctions compared with peers without such economic problems. In women, there was also a statistically significant trend of increasing sexual dysfunction prevalence with decreasing household income, and women living in Copenhagen or other large cities more frequently reported sexual dysfunction than women in rural areas. Somewhat surprisingly, however, women with long school attendance and those with high post-secondary education were more likely to report sexual dysfunction than women with lower education. In a supplementary regression model we learned that the significant associations of place of residence, years of school attendance and post-secondary education with sexual dysfunctions overall were not materially confounded by household income. Similarly, the significant association between household income and sexual dysfunctions overall was not explained by the two education variables. Our study therefore suggests that measures of economic hardship (both sexes), high level of education (women) and urban life (women) are somehow associated, and independently so, with an increased prevalence of sexual dysfunctions. It is unclear, however, whether the latter two observations reflect true differences in female sexual dysfunction prevalence according to educational level and place of residence. We cannot exclude that women with low or no education and those living in rural areas might have been less likely than well-educated women and women living in large cities to report details about sexual trouble in the underlying population survey.

Several previous studies have reported on the possible associations between sociodemographic factors and male sexual dysfunction. One study found erectile dysfunction to be more prevalent in men with low income, low education, and those without a spouse (Ahn et al., 2007), and several other studies, though not all (Chew et al., 2008), have reported a higher prevalence of erectile dysfunction among men with limited education (Nicolosi, Moreira, Shirai, Bin Mohd Tambi, & Glasser, 2003b; Lyngdorf & Hemmingsen, 2004; Nicolosi et al., 2003a; Selvin, Burnett, & Platz, 2007) and among unmarried men (Chew et al., 2008; Mak, De, Kornitzer, & De Meyer, 2002; Moreira et al., 2002; Nicolosi et al., 2003b). Our findings do not confirm these prior observations regarding erectile dysfunction in a Danish setting. The only sociodemographic factor that exhibited a statistically significant association with erectile dysfunction was current unemployment. Men who were unemployed were three times more likely to report erectile dysfunction than men who currently had a job. The discrepancy between our and previous findings may, at least in part, be due to differences in the used definitions of erectile dysfunction. For instance, after adjusting for age unmarried and divorced men in our study reported erectile difficulties that were not severe enough to be considered a sexual dysfunction significantly more often than did men who were married. Economic problems and low income have also been linked to orgasm difficulties in men (Laumann et al., 2005) and with premature ejaculation (Moreira, Kim, Glasser, & Gingell, 2006). This is in agreement with our finding that men with premature ejaculation had three times greater odds of reporting difficulties paying their bills than men without premature ejaculation.

A previous study of 40 year-old Danish women showed an association between low social status and low orgasm frequency (Garde & Lunde, 1984), findings which accord well with the associations that we observed with economic hardship in the family. However, a general pattern of higher rates of sexual dysfunctions in socially underprivileged women was not observed in neighboring Sweden (Öberg et al., 2004). With a higher prevalence of vaginismus among less educated women and first generation immigrants as the only exceptions, Öberg et al. found no significant relationship between a number of sociodemographic items and sexual dysfunction prevalence. Considering the cultural, socioeconomic, and behavioral similarities that exist between Denmark and Sweden, it is unclear why patterns of association between socioeconomic measures and sexual dysfunctions would differ so markedly between these two countries. Unlike the situation for Swedish women, our study suggests that socioeconomically underprivileged Danes of both sexes have a higher prevalence of sexual dysfunctions.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study is based on a large, population-based sample that is believed to be representative of the Danish population (Rasmussen & Kjøller, 2004). Further, we consider it a strength that we address four classical sexual dysfunctions in each sex, and we provide prevalence estimates for less severe sexual difficulties which may facilitate meaningful comparisons with prevalence estimates in other studies that used different criteria to define sexual dysfunction. However, our study shares the difficulty in achieving high participation rates (men 48%, women 54%) with other studies in the field, whose reported participation rates ranged between 19% and 78% (Chew et al., 2008; Dunn, Croft, & Hackett, 1998; Laumann et al., 2005; Lyngdorf & Hemmingsen, 2004; Moreira et al., 2006; Selvin et al., 2007). Of participants who returned the questionnaires, we included those who were sexually active in our analyses, representing 82% of men and 77% of women. These proportions of sexually active persons are comparable with a study of 1,500 men and women aged 40–80 years in Germany, among whom 86% of men and 66% of women reported having had sexual intercourse in the previous year (Moreira, Hartmann, Glasser, & Gingell, 2005). A higher proportion of sexually active women (86%) was reported in Sweden, which is likely to reflect that study’s restriction to 18- to 65-year-old women (Öberg et al., 2004). Some participants in our study who were excluded because they were not sexually active may have been sexually inactive because of one or more of the sexual dysfunctions studied, as suggested by reports of high prevalence of erectile dysfunction in sexually inactive men (Nicolosi et al., 2003b). Consequently, our prevalence estimates for the studied sexual dysfunctions may not apply to the entire population, but they are most likely valid for the sexually active majority of the Danish population. Unfortunately, the way questions were asked in our study provided us with no opportunity to examine the burden of sexual dysfunctions among those who were sexually inactive.

In conclusion, sexual difficulties were reported by 79–80% of sexually active men and women in Denmark. Approximately one in nine, 11%, experienced sexual difficulties severe enough to be considered clinically relevant sexual dysfunctions. Measures of economic hardship in the family were associated with an increased prevalence of sexual dysfunctions in both sexes, implying that social inequalities in health may also apply to sexual health. Future studies that aim to identify the underlying causes of sexual dysfunctions should address and, when relevant, adjust for the possible influence of socioeconomic confounders.

References

Ahn, T. Y., Park, J. K., Lee, S. W., Hong, J. H., Park, N. C., Kim, J. J., et al. (2007). Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in Korean men: Results of an epidemiological study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 4, 1269–1276.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

Chew, K. K., Stuckey, B., Bremner, A., Earle, C., & Jamrozik, K. (2008). Male erectile dysfunction: Its prevalence in Western Australia and associated sociodemographic factors. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5, 60–69.

Dalton, S. O., Schüz, J., Engholm, G., Johansen, C., Kjær, S. K., Steding-Jessen, M., et al. (2008). Social inequality in incidence of and survival from cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994–2003: Summary of findings. European Journal of Cancer, 44, 2074–2085.

Dunn, K. M., Croft, P. R., & Hackett, G. I. (1998). Sexual problems: A study of the prevalence and need for health care in the general population. Family Practice, 15, 519–524.

Eplov, L., Giraldi, A., Davidsen, M., Garde, K., & Kamper-Jørgensen, F. (2007). Sexual desire in a nationally representative Danish population. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 4, 47–56.

Fugl-Meyer, A. R., & Fugl-Meyer, K. S. (1999). Sexual disabilities, problems and satisfaction in 18–74 year old Swedes. Scandinavian Journal of Sexology, 2, 79–105.

Garde, K., & Lunde, I. (1984). Influence of social status on female sexual behaviour. A random sample study of 40-year-old Danish women. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 2, 5–10.

Graugaard, C., Eplov, L. F., Giraldi, A., Kristensen, E., Munck, E., & Møhl, B. (2004). Denmark. In R. T. Francoeur & R. J. Noonan (Eds.), International encyclopedia of sexuality (pp. 329–344). New York: Continuum.

Harrell, F. (2001). Regression modeling strategies: With applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Laumann, E. O., Nicolosi, A., Glasser, D. B., Paik, A., Gingell, C., Moreira, E., et al. (2005). Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 y: Prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. International Journal of Impotence Research, 17, 39–57.

Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., & Rosen, R. C. (1999). Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. Journal of the American Medical Association, 281, 537–544.

Lewis, R. W., Fugl-Meyer, K. S., Bosch, R., Fugl-Meyer, A. R., Laumann, E. O., & Lizza, E. (2004). Definitions, classification, and epidemiology of sexual dysfunction. In T. F. Lue, R. Basson, R. Rosen, F. Giuliano, S. Khoury, & F. Montorsi (Eds.), Sexual medicine: Sexual dysfunction in men and women (pp. 37–72). Paris: Health Publications.

Lyngdorf, P., & Hemmingsen, L. (2004). Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction and its risk factors: A practice-based study in Denmark. International Journal of Impotence Research, 16, 105–111.

Mak, R., De, B. G., Kornitzer, M., & De Meyer, J. M. (2002). Prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction in a population-based study in Belgium. European Urology, 41, 132–138.

Mercer, C. H., Fenton, K. A., Johnson, A. M., Copas, A. J., Macdowall, W., Erens, B., et al. (2005). Who reports sexual function problems? Empirical evidence from Britain’s 2000 national survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 81, 394–399.

Mercer, C. H., Fenton, K. A., Johnson, A. M., Wellings, K., Macdowall, W., McManus, S., et al. (2003). Sexual function problems and help seeking behaviour in Britain: National probability sample survey. British Medical Journal, 327, 426–427.

Montorsi, F. (2005). Prevalence of premature ejaculation: A global and regional perspective. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 2(Suppl 2), 96–102.

Moreira, E. D., Hartmann, U., Glasser, D. B., & Gingell, C. (2005). A population survey of sexual activity, sexual dysfunction and associated help-seeking behavior in middle-aged and older adults in Germany. European Journal of Medical Research, 10, 434–443.

Moreira, E. D., Kim, S. C., Glasser, D., & Gingell, C. (2006). Sexual activity, prevalence of sexual problems, and associated help-seeking patterns in men and women aged 40–80 years in Korea: Data from the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors (GSSAB). Journal of Sexual Medicine, 3, 201–211.

Moreira, E. D., Lisboa Lobo, C. F., Villa, M., Nicolosi, A., & Glasser, D. B. (2002). Prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction in Salvador, northeastern Brazil: A population-based study. International Journal of Impotence Research, 14(Suppl 2), S3–S9.

Nazareth, I., Boynton, P., & King, M. (2003). Problems with sexual function in people attending London general practitioners: Cross sectional study. British Medical Journal, 327, 423–426.

Nicolosi, A., Glasser, D. B., Moreira, E. D., & Villa, M. (2003a). Prevalence of erectile dysfunction and associated factors among men without concomitant diseases: A population study. International Journal of Impotence Research, 15, 253–257.

Nicolosi, A., Moreira, E. D., Shirai, M., Bin Mohd Tambi, M. I., & Glasser, D. B. (2003b). Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction in four countries: Cross-national study of the prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction. Urology, 61, 201–206.

Öberg, K., Fugl-Meyer, A. R., & Fugl-Meyer, K. S. (2004). On categorization and quantification of women’s sexual dysfunctions: An epidemiological approach. International Journal of Impotence Research, 16, 261–269.

Pedersen, C. B., Gøtzsche, H., Møller, J. O., & Mortensen, P. B. (2006). The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Danish Medical Bulletin, 53, 441–449.

Rasmussen, N. K., & Kjøller, M. (2004). The National Institute of Public Health’s program for health and morbidity surveys. Ugeskrift for Laeger, 166, 1438–1441.

Richters, J., Grulich, A. E., de Visser, R. O., Smith, A. M., & Rissel, C. E. (2003). Sex in Australia: Sexual difficulties in a representative sample of adults. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 27, 164–170.

Selvin, E., Burnett, A. L., & Platz, E. A. (2007). Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. American Journal of Medicine, 120, 151–157.

The Danish Ministry of Health. (2000). Social inequality in health. Differences in health, lifestyle, and use of the health care system. Copenhagen: Nyt Nordisk Forlag Arnold Busck A/S.

Ventegodt, S. (1998). Sex and the quality of life in Denmark. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 27, 295–307.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Danish Medical Research Council, the Lundbeck Foundation, The Health Insurance Foundation, Aase and Einar Danielsens Foundation, Carl J. Beckers Foundation, Frode V. Nyegaard and wife’s Foundation, Krista and Viggo Petersens Foundation, and Torben and Alice Frimodts Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Christensen, B.S., Grønbæk, M., Osler, M. et al. Sexual Dysfunctions and Difficulties in Denmark: Prevalence and Associated Sociodemographic Factors. Arch Sex Behav 40, 121–132 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9599-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9599-y