Abstract

Epidemiologic studies of sexual function problems in men have focused on the individual male and related sociodemographic characteristics, individual risk factors and lifestyle concomitants, or medical comorbidities. Insufficient attention has been given to the role of sexual and relationship satisfaction and, more particularly, to the perspective of the couple as causes or correlates of sexual problems in men or women. Previously, we reported results of the first large, multi-national study of sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in 1,009 midlife and older couples in five countries (Brazil, Germany, Japan, Spain, U.S.). For the present study, we examined, within each problem, the association of four major sexual problems in men (loss of sexual desire, erectile problems, premature ejaculation, delayed/absent orgasm) and multiple problems, with male and female partners’ assessments of physical intimacy, sexual satisfaction, and relationship happiness, as well as associations with well-known health and psychosocial correlates of sexual problems in men. Sexual problem rates of men in our survey were generally similar to rates observed in past surveys in the general population, and similar risk factors (age, relationship duration, overall health) were associated with lack of desire, anorgasmia, or erection difficulties in our sample. As in previous surveys, there were few correlates of premature ejaculation. As predicted, men with one or more sexual problems reported decreased relationship happiness as well as decreased sexual satisfaction compared to men without sexual problems. Moreover, female partners of men with sexual problems had reduced relationship happiness and sexual satisfaction, although these latter outcomes were less affected in the women than the men. The association of men’s sexual problems with men’s and women’s satisfaction and relationship happiness were modest, as these couples in long-term, committed relationships were notable for their relatively high levels of physical affection and relationship happiness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the consequences of the upsurge in interest in erectile dysfunction (ED) and premature ejaculation, among other male sexual performance problems, is the publication of several large-scale community-based surveys of sexual problems among heterosexual men in the community (Kupelian, Araujo, Chiu, Rosen, & McKinlay, 2010; Laumann, Paik, & Rosen, 1999; Lindau et al., 2007). Findings from these community surveys have raised awareness of the role of sociodemographic factors, medical comorbidities, and lifestyle variables in male sexual problems generally and erectile dysfunction (ED) in particular (Araujo et al., 2010; Kupelian et al., 2010; Nicolosi et al., 2006; Rosen et al., 2004; Travison et al., 2011). Furthermore, studies have highlighted the role of cardiovascular disease factors and metabolic concomitants of ED in particular (Araujo et al., 2010; Chew et al., 2010; Inman et al., 2009). Much less attention has been given to the role of men’s emotional or interpersonal responses, although other studies have begun to examine the issue (Fisher et al., 2004a). Does this imply that emotional and interpersonal factors are less critical influences on men’s as compared to women’s sexual function or satisfaction, or that they are less important to study? And how much overlap and similarity is there in the response of the couple to male sexual problems: do male or female partners differ in their responses to ED or other common sexual problems in men? Moreover, few studies have attended to process factors, such as men’s adaptation to one or more sexual problems over time, and the corresponding responses of his partner.

How men and women view erectile dysfunction has been directly investigated in only one large survey study to date (Fisher, Eardley, McCabe, & Sand, 2009a, b). For this study, surveys were sent to female partners of men who had participated in the Men’s Attitudes to Life Events and Sexuality (MALES) study, a large multi-national survey of 27,000 men in 8 countries (United States, United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Mexico, Brazil) (Eardley et al., 2007; Fisher et al., 2004a; Rosen et al., 2004). In one set of analyses, Fisher et al. (2009a) observed that partners shared a high level of concordance in their perceptions of the severity and impact of the male’s ED, as well as their perceptions of the available options for treating the problem (Fisher et al., 2009a). In a second publication, it was noted that female partner’s attitudes and understanding of ED influenced the male partner’s ultimate decision to seek treatment (Fisher et al., 2009b). In related findings, it has been demonstrated that female partners of men with ED report a substantial decline in all aspects of sexual function (Fisher, Rosen, Eardley, Sand, & Goldstein, 2005) and that treatment of the male partner’s ED results in substantial improvement in female partners’ sexual function (Goldstein et al., 2005; Heiman et al., 2007). The current study extends work on elucidating men’s sexual problems in the couple context, by assessing specific male sexual problems, and male and female couple members’ sexual and relationship satisfaction, in a highly structured way, including men’s and women’s perceptions of sexual problems in either partner. We have specifically expanded our investigation to include common male problems beyond ED, including lack of sexual desire and orgasm difficulties, in addition to the presence of multiple sexual problems in one individual, along with the related sexual and relationship effects for both partners in the relationship.

This study builds on earlier findings from the International Survey of Relationships (ISR) (Fisher et al., 2014; Heiman et al., 2011), which examined patterns of relationship and sexual satisfaction in a large multi-national community sample of couples. In the present study, we investigated male and female partners’ sexual and relationship satisfaction and perception of common male sexual performance problems, including erectile difficulty (ED), premature ejaculation (PE), delayed/absent orgasm (OD) and hypoactive sexual desire (HSD), or lack of sexual interest or desire. These four well-known and widely studied sexual problems in men correspond to four of the main categories of male sexual dysfunction in DSM-IV and DSM-5, although the duration requirements and other qualifiers have been modified in DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In keeping with DSM-5 definitions of sexual dysfunction in men and women, we assessed bother or distress associated with the occurrence of a sexual problem, and required at least a moderate level of bother for case definition.

The International Survey of Relationships (ISR) (Fisher et al., 2014; Heiman et al., 2011) is the first multi-national study assessing couple relationship aspects of sexual health in diverse samples of middle-aged and older men and women in five countries (Brazil, Germany, Japan, Spain, U.S.). The study was uniquely designed to assess, in a relatively large and diverse sample of couples in committed relationships, the association between sexual and relationship satisfaction-related variables in these couples (Heiman et al., 2011). We have previously reported that sexual functioning was important for predicting sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in both men and women. In addition to the contribution of sexual functioning, sexual satisfaction for men was also predicted by good health, kissing and cuddling often, being caressed by their partner often, greater importance of their partner’s orgasm during sex, more frequent sex, and fewer lifetime sexual partners (Heiman et al., 2011). Using dyadic analyses, even after controlling for individual-level effects, partners’ reports of the following variables contributed significantly to predicting and understanding individuals’ sexual satisfaction: good health; frequent kissing, cuddling, and caressing; frequent recent sexual activity; attaching importance to one’s own and one’s partner’s orgasm; better sexual functioning; and greater relationship happiness (Fisher et al., 2014). Correlates of relationship happiness included individuals’ reports of good health; frequent kissing, cuddling, and caressing; frequent recent sexual activity; attaching importance to one’s own and one’s partner’s orgasm; better sexual functioning; and greater sexual satisfaction. Once again, even after controlling for individual-level effects, partners’ reports of each of these correlates contributed significantly to predicting and understanding individuals’ relationship happiness.

For purposes of the present analyses, we examined the association between four common distressing sexual problems in men (lack of desire or erection; delayed orgasm, premature ejaculation) and their association with sexual and relationship satisfaction among male and female partners in long-term couple relationships. Based on conceptualizations of couple level dynamics linking couple intimacy, relationship satisfaction, and sexual satisfaction, and extant empirical research in this connection (Birnbaum, Reis, Mikuliner, Gillath, & Orpaz, 2006; Butzer & Campbell, 2008; Byers, 2005; Fisher et al., 2009a, 2009b; Heiman et al., 2011; Rubin & Campbell, 2012), we hypothesized that there will be a high level of concordance of male and female partners’ perceptions of these sexual problems and of their impact on sexual and relationship satisfaction. We predicted that relationship satisfaction in men and women would be positively correlated with their own sexual satisfaction and with their own (men) and partner’s (women) sexual problems or lack of problems. We further predicted that female partners of men with sexual problems would report lower sexual and relationship satisfaction compared to female partners of men without sexual problems. Finally, given the long relationship duration of many couples in this study, we expected female partners to show some level of adaptation (evident in ratings of emotional closeness and relationship happiness) to male partners in the context of their ongoing sexual problems; however we also used these data to explore alternative patterns of partner response in our cohort.

Method

Study Design

The study employed survey methodology in a large, international sample to investigate sexual and relationship variables and their association with sexual functioning and sexual experiences in middle-aged and older couples in committed relationships of varying duration. Variables for the study were selected by the authors after extensive review of published literature and recent large-scale survey studies (Fisher et al., 2009a; Heiman et al., 2011; Nicolosi et al., 2006; Rosen et al., 2004). Survey research was conducted in Brazil, Germany, Japan, Spain, and the U.S. targeting 200 men aged 40–70 and their female partners in each country, with 1,009 couples in the final sample. Selected demographic variables were identified prior to the study, including brief and culturally validated measures of overall health, physical intimacy, sexual history, sexual functioning, and sexual and relationship satisfaction variables to permit analyses of interactions across and within couples.

For the present study, we considered responses of male participants to questions about their sexual satisfaction and whether or not they experienced sexual problems and related distress, as well as their association with overall sexual and relationship satisfaction, compared to men without sexual problems. We considered female partners’ responses to parallel questions corresponding to each of these common male problems. Our analyses examined the association between pre-specified sociodemographic and relationship variables, self-ratings of sexual and relationship problems, and their association across the sample with relationship happiness or sexual satisfaction.

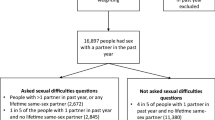

Participants

Five countries were included in the current research: Brazil, Germany, Japan, Spain, and the U.S. A benchmark of 200 couples was set for each country with the final sample including 1,009 couples (2,018 individuals): 207 couples from each of Japan and the U.S.; 198 couples from Brazil and Germany; and 199 couples from Spain. Sampling targeted men aged 40–70 and their female partners, in committed relationships, either married or living with a partner for a minimum of 1 year. Men in the sample ranged in age from 39 to 70 with a median age of 55. Female partners ranged in age from 25 to 76 with a median age of 52. Ninety percent of the couples had children. Gender-specific questionnaires were administered for each partner, with couples instructed not to discuss their answers with their partner until all questionnaires were completed and returned. Participant recruitment and data collection were directed and managed by Synovate Healthcare, an international healthcare market research company, and varied by country, using sampling strategies standard for each country. In the U.S., Germany, and Spain, participants were recruited by phone, using both random digit dialing (RDD) techniques and established market databases, and then sent questionnaires by mail for self-completion. In Brazil and Japan, recruitment was done door-to-door, within large cities for Brazil, and within randomly sampled locales for Japan, and questionnaires then left for respondent self-completion. Quota samples based on age were used in all countries. Except for Japan, quota sampling for geographic regions was also used. Initial Synovate response rates, before finding out about the sexual content of the survey, were calculated only for the U.S. Refusal rates due to sexual content varied between 2.9 % (Brazil) to 17.2 % (U.S.). Details on sampling may be found in Heiman et al. (2011).

Measures

The International Survey of Relationships (ISR) is a multi-dimensional, paper-and-pencil survey instrument assessing domains of demographics, health, mood, selected sexual history, sexual behaviors and sexual experiences over the past 4 weeks and 12 months, and respondent ratings of the importance of different life areas and sexual activities. The ISR includes 125 questions, many of which were selected from existing measures and standardized questionnaires, with a number of questions developed specifically for this study.Footnote 1 The survey was constructed by the authors to provide potentially important information for increasing our knowledge of enduring relationships and for designing future clinical programs dealing with sexual and relationship quality in older adults. The survey was described to participants as “…a study about people’s relationships and their happiness with them. A number of questions deal with aspects of your personal relationship, including sexuality and sexual experiences.” Participants were assured that their responses would be confidential, not shared with their partner, and only analyzed in the aggregate with responses never connected to a specific individual. The survey was translated and back-translated for the given language in the countries involved. The study received approval from the Indiana University Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Sexual Problems

Four well-known, common male problems were identified for our study along with associated bother. The specific questions used for assessing the prevalence of these problems were adapted from the National Health and Social Life Survey (NHSLS) (Laumann et al., 1999). A bother question was added with each sexual problem as follows:

-

(1)

Hypoactive Sexual Desire (HSD): In the last year, for a period of 1 month or longer, have you lacked interest in having sex? (Y/N) Bother/Distress: Have you been bothered by your lack of interest? (Not at all bothered/Somewhat bothered/Very bothered)

-

(2)

Erection Difficulty (ED). Question: In the last year, for a period of 1 month or more, did you have trouble achieving or maintaining an erection (Y/N): Have you been bothered by your trouble with erections? Bother/Distress: (Not at all bothered/Somewhat bothered/Very bothered).

-

(3)

Premature ejaculation (PE). Question: In the last year, for a period of 1 month or more, did you experience orgasm too quickly? (Y/N) Bother/Distress: Have you been bothered by your orgasm occurring too quickly? (Not at all bothered/Somewhat bothered/Very bothered).

-

(4)

Delayed Orgasm/Anorgasmia (OD). Question: In the last year, for a period of 1 month or more, were you were unable to experience an orgasm? (Y/N)? Bother/Distress: Have you been bothered by your inability to experience orgasm? (Not at all bothered/Somewhat bothered/Very bothered).

The “mixed sexual problem” group was defined as having more than one of the above problems, and were somewhat or very bothered in association with the problem. Finally, the “no problem” group comprised the majority (57 %) of men in our sample.

Sociodemographic and Control Variables

As in our previous reports (Fisher et al., 2014; Heiman et al., 2011), age, geographic location, relationship status and duration, education, and self-reported health were used as sociodemographic marker variables and health controls (see “Appendix” section for a description of each of the variables and their response categories). Education was measured with a five-category scale as described in Heiman et al. (2011). Relationship status (married, cohabitating) and relationship duration were defined similarly. Subjective self-rating of overall health was obtained by means of a binary indicator of self-perceived health (see “Appendix” section). Measures of relationship happiness and sexual satisfaction, which were analyzed extensively in our previous publication (Fisher et al., 2014; Heiman et al., 2011), were assessed as follows: The relationship happiness question was adapted from the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976) and included the response categories: very unhappy, fairly unhappy, a little unhappy, happy, very happy, extremely happy, and perfect. Due to small marginal distributions for some categories, our analyses of relationship happiness used a dichotomized measure comparing happy to unhappy relationships by collapsing across the original seven categories (Heiman et al., 2011). Sexual satisfaction was adapted from the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) (Rosen et al., 1997, 2000). Responses were combined into two categories: not satisfied comprised the first three responses and satisfied comprised the latter two (see “Appendix” section).

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons of differences in mean levels of control and predictor variables for men and partners of men with or without sexual problems were performed. Comparisons were made using t-tests for continuous measures (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). Chi-square tests were used to test the relationship between levels of distress and self-ratings of sexual and relationship satisfaction for each sexual problem (Table 6). The logit model for predictors of sexual problems, as shown in Table 8, was estimated using maximum likelihood with robust standard errors that adjust for clustering by country. Duration of the relationship and duration squared were included to allow for nonlinear effects of duration on the probability of having one or more problems. Multiplicity adjustments were not utilized since all analyses were deemed exploratory. For further details, see Long and Freese (2005).

Results

Sample Characteristics and Problem Predictors

Characteristics of male and female respondents in the sample are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The average age of men in the study was 55.0 years, with men having one or more type of sexual problem being 3.9 years older on average than men without any sexual problems (p < .001). Female partners had a mean age of 51.5 years, with partners of men with one or more problems being significantly older (53.7 years) compared to female partners of men without sexual problems (49.8 years) (p < .0001). The large majority of both groups were married with no significant differences between couples with or without sexual problems, as expected within a sample selected for enduring relationships. Relationship duration was 22.7 years for men without sexual problems, compared to 28.2 years for men with one or more problem, in keeping with the older age of men with sexual problems. Among variables associated with the presence or absence of sexual problems in the men, relationship duration was inversely related to positive sexual function, with longer partner relationships associated with more frequent problems in the men (p < .001).

Men with problems reported poorer subjective health, a greater number of self-reported physical and mental health problems, and more cardiovascular disease (p < .001). In contrast, no significant differences in overall subjective health were noted between female partners of men with and without sexual problems (p = .141), although female partners of men with problems reported a higher rate of cardiovascular disease and other specific health problems than partners of men without problems (Table 2). Both men with sexual problems and their partners reported reduced rates of physical affection (p < .001) and sexual satisfaction (p < .001). While relationship happiness was also reduced in men with any sexual problems (p = .014), no significant differences were observed in reported relationship satisfaction in female partners of men with and without sexual problems (Table 2). Other lifestyle factors, including BMI, days per week of alcohol use, and frequency of exercise and smoking were not significantly associated with sexual problem status in either males with sexual problems or their female partners.

Specific Male Problems

Table 4 shows predictors of sexual problem status in men. The presence of erection problems was associated with older age (p < .001), longer relationship duration (p < .001), less satisfactory overall health (p = .002), and less sexual satisfaction (p < .001). However, erectile dysfunction status was not significantly associated with relationship happiness (p = .12) in our sample of men in stable, long-term relationships. Table 4 demonstrates a similar pattern of predictors observed for sexual desire problems and male orgasmic disorder among male participants in our survey and their partners. A different pattern of predictors was evident with premature ejaculation, however, which was negatively correlated with sexual satisfaction in men, but not with relationship satisfaction or other sociodemographic or health predictors. Age and common comorbidities did not play a significant role as predictors of premature ejaculation, in contrast to the pattern observed for the three other major categories of sexual problems in men or for men who had more than one of these problems (see Tables 1, 2).

Men with multiple sexual problems reported similar rates of overall sexual dissatisfaction and relationship distress compared to men with single problems (Table 4). As reported previously, tetrachoric correlations between our binary measures of sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness by gender were .40 for men and .41 for women, indicating 16 % shared variation between the dependent variables (Heiman et al., 2011).

Self and Female Partner Ratings

Table 5 presents the corresponding comparisons for female partners of men with and without sexual problems. Similar to the findings for their male partners, women whose partners had sexual problems other than PE were significantly older, had been longer in their primary relationship, and reported less sexual satisfaction and emotional closeness satisfaction during sex. As noted, female partners of men with erection problems or lack of orgasm similarly reported less happy relationships. In contrast to the results for men with problems, our partners of men with sexual problems reported similar levels of overall health to partners of men without problems. Partner’s health did not affect sexual function or satisfaction in our sample.

Self-ratings of emotional closeness during sex and overall sexual satisfaction were significantly associated with the level of distress or bother associated with sexual problems among men in our sample. Overall, we observed an increased tendency toward less positive sexual or emotional outcomes with higher levels of sexual bother or distress among the men. Emotional closeness satisfaction during sex, for example, was reported by 73 % of men with no bother about ED, compared to 58 % of men with some distress about the problem, and 49 % of men with severe distress about their erection problem. Similarly, sexual satisfaction was reported by 70 % of men with no distress about ED, compared to 50 % of men with some level of bother and 32 % of men with severe bother concerning their erection. A similar pattern of association was observed for the other male sexual problems (see Table 6).

We selected variables to examine possible differences in ratings between partners (Table 7). Partners’ ratings of happiness in the relationship, emotional closeness during sexual activity, sexual satisfaction, worry about the current sexual relationship, and frequency of kissing and cuddling were examined as a function of the presence or absence of each of the male sexual problems assessed. Ratings of these variables were generally similar across male and female partners, with the largest difference in ratings of sexual satisfaction in couples with a male partner having sexual problems. Notably, in these couples, men consistently rated their level of sexual satisfaction as lower than their female partners. For the ratings of emotional closeness during sex, partners of men with PE reported less emotional closeness satisfaction during sex (p = .014), as did partners of men with hypoactive desire (p < .04), but this pattern was not observed for the other male sexual problems. Ratings of relationship happiness and frequently kissing and cuddling were generally consistent across men and women.

Modeling Results

Table 8 shows the odds ratios from a binary logit model of sexual problems for the men. The odds ratio indicates the factor change in the odds of a man having one or more problems for a unit increase in a given variable, holding other variables constant. Age at the start of the relationship was statistically significant, with a 5-year increase in age increasing the odds of a sexual problem by a factor of 1.12 (= 1.025). The duration of the relationship had a strong and significant effect on the presence or absence of sexual problems, LR χ 2(2) = 68.19, p < .001, even when controlling for male partner age and other variables. As shown in Fig. 1, the probability of a man reporting sexual problems increased from .25 at the outset of the relationship to .60 in year 40 and nearly .80 in the 50th year of the relationship, even after holding age and other variables constant. Being in good health decreased the odds of having a sexual problem by a factor of .71, while being sexually satisfied decreased the odds by half. The effects of being happy in the relationship and frequency of being touched/caressed by one’s partner were not significant (this variable was selected from the Heiman et al., 2011 report because it demonstrated strong predictive value for sexual satisfaction). Country-level patterns indicated that Spanish and German men had lower odds of self-reported problems relative to US men.

Discussion

The current study offers a complementary, couple-focused perspective on common male sexual problems in a large, multi-national sample of more than 1,000 couples in five countries (Fisher et al., 2014; Heiman et al., 2011). Whereas prior studies have focused largely on the role of sociodemographic factors and medical comorbidities as predictors of sexual problems in men (Kupelian et al., 2010; Lindau et al., 2007; Nicolosi et al., 2006; Rosen et al., 2004; Travison et al., 2011), our study places at the forefront the perspective of couples who have the opportunity to evaluate their sexual problem and their response to it in the course of a long-term, committed relationship.

This perspective is novel and complements findings from our own (Fisher et al., 2014; Heiman et al., 2011) and others (Fisher et al., 2005, 2009a) on the need for a more couples-oriented perspective on male sexual dysfunction. In a recent study (Fisher et al., 2014), we have shown that the prediction and understanding of men’s and women’s sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness is conditional on conceptual and statistical recognition of the partner’s characteristics and perceptions and how these contribute to these couple outcomes. In short, the individual’s partner and his/her perspective always matters to the prediction and understanding of the individual’s sexual and relationship satisfaction, and the current study extends this perspective to understanding the correlates of common male sexual problems.

In the current study, to assess the relative impact of sexual problems in men, we compared the presence or absence of four common male sexual problems (lack of desire or erection, delayed orgasm, premature ejaculation), and combinations of sexual problems for their association with self- and partner happiness and satisfaction. We aimed for a conservative definition of sexual problem via the requirement for personal distress as a necessary component, but should acknowledge that men may have used different criteria for assessing subjective distress. This has not been independently investigated and is recognized as a limitation in our definition.

We incorporated sociodemographic and typical health status predictors (e.g., age, partner status, chronic illnesses and comorbidities, prescription medication) and analyzed outcomes of interpersonal and partner-related distress associated with common sexual problems. These analyses were performed on men of varying ages between 39 and 70, from different geographic and cultural backgrounds. Similar data on male sexual problems are not available for any comparable, highly diverse sample of men in long-term partner relationships and provide a novel and unique contribution to the literature on male sexual dysfunction.

Overall, the men in our sample were in their mid-50 s on average, married, and in long-term, committed relationships of 22–28 years. Roughly 80 % reported they were happy in their relationship with their partner, while 74 % of the men with no sexual problems reported being moderately or highly sexually satisfied. An interesting finding in the current study is the strong association of relationship duration with the presence of sexual problems and associated bother or distress. There are some important methodological limitations and weaknesses to be acknowledged in our current study. Importantly, we noted previously that differences in the sampling recruitment methods (telephone vs internet-based) may have confounded geographic differences (Fisher et al., 2014; Heiman et al., 2011) and thus we do not focus on country differences. Another significant limitation is the availability of only cross-sectional data from a single time point, which restricts our ability to interpret causal relationships in the data or to make longitudinal predictions.

Among demographic variables in our study, age and perceived health were significant correlates of three of the four common sexual problems in men, including erection difficulties, loss of desire and orgasmic disorder, as well as in the mixed problem group. Relationship duration was similarly an important predictor, independent of age, physical health, or other factors. Premature ejaculation was an outlier among sexual problems in failing to show the typical associations between age, physical health, and the usual comorbidity factors. On the other hand, men with multiple sexual problems showed a very similar pattern of correlates and comorbidities to the men with ED alone, anorgasmia, or low desire. These findings are consistent with previous research showing similar associations between other male problems and aging or age-related health difficulties in men. (Laumann et al., 2006; Rosen et al., 2004; Travison et al., 2011). Not previously noted, increasing severity of sexually related distress was significantly associated with diminished relationship happiness for men with low desire and orgasmic disorder, but not for men with ED or PE. In contrast, sexual satisfaction, emotional closeness during sex, and overall sexual function were all significantly reduced in men with all four problems in our findings.

A unique aspect of this study is the comparison of partner ratings of sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness for couples with and without male sexual problems. Both sexual and relationship satisfaction were adversely impacted in men with sexual problems compared to men without, although relationship satisfaction continued to be relatively high overall. In contrast, partners of men with sexual problems had lower ratings of sexual satisfaction, but relationship satisfaction was relatively unaffected in these women. Moreover, men with loss of desire and premature ejaculation reported less emotional intimacy satisfaction during sex than their female partners. Not surprisingly, men with one or more sexual problem were more likely than their female partners to report being concerned about the effect of their problem on the sexual or couple’s relationship. Of note, both partners reported similar frequencies of kissing and cuddling (i.e., physical intimacy) regardless of the sexual problem status of the male partner, although the level of physical intimacy reported was generally lower for both men with problems and their partners. Taken together, these findings suggest that despite the negative impact on sexual function and sexual satisfaction in men with common sexual problems, this large, multi-national sample of couples in long-term, committed relationships continued to enjoy at least modest levels of emotional and physical intimacy, and to experience relatively high degrees of relationship happiness (cf. Liu, 2003).

What are the theoretical or clinical implications of these findings? To understand the observed pattern of similarities and differences among the common male sexual problems under study, some key observations should be made. First, for lack of desire or erection and delayed orgasm, or combinations of these problems, older age, relationship duration, and self-reported health were consistent predictors across countries and age groups. For erection problems and to a lesser degree also for delayed orgasm or loss of desire, age and health status are probable indicators or underlying cardiovascular morbidities that serve as an organic foundation for these common problems (Chew et al., 2010; Inman et al., 2009; Kupelian et al., 2010). It is also possible that age and cardiovascular morbidity contribute directly to erection problems (Kupelian et al., 2010), and that loss of erection contributes to the development over time of delayed orgasm and desire loss (Nicolosi et al., 2006). It may also be the case that men’s age and relationship duration co-vary with their partner’s age and relationship duration and that these time-related changes contribute to psychological habituation or adaptation to the sexual relationship and its changes (Fisher et al., 2009a; Shifren, Monz, Russo, Segreti, & Johannes, 2008). Such time-related changes also co-vary with possible decline in cardiovascular health, all of which may act synergistically to contribute organic, individual psychological, and relationship influences on loss of desire or erection, or delayed orgasm. Premature ejaculation, in contrast to other common sexual problems in men, shows few associations with age and health status and appears less linked to aging or medical comorbidities in men, as has been shown previously (Nicolosi et al., 2006; Porst et al., 2007). At the same time, the problem is associated with decreased sexual and relationship satisfaction, associations that are plausibly bidirectional in nature, with premature ejaculation leading to decreased sexual and relationship satisfaction, and low levels of sexual and relationship satisfaction contributing to and perhaps maintaining PE (Porst et al., 2007; Rosen & Althof, 2008).

With respect to cross-country differences, definitive conclusions cannot be drawn since there were marked differences in the sampling methodology from one country to another (Heiman et al., 2011). The prevalence results by country are descriptive of possible patterns than may be explored in future studies using a cross-cultural representative sample design. For example, a “standout” prevalence of erection problems was observed in the U.S. sample, and one could conjecture that American respondents, perhaps influenced by pervasive advertisements of PDE5 inhibitors that have saturated the U.S. media, may assume that erection problems are common, normative, and acceptable to acknowledge, and may report erection problems at relatively high levels. The major problem in our Japanese sample was low desire, and one may speculate that cultural norms of restraint and assumptions about age and sexuality may have influenced either the actual prevalence of low desire in Japanese men or the likelihood of reporting it. Focused research would be useful to determine how culturally specific expectations and norms might explain some of the variance suggested by the country-level reports of sexual problem prevalence in our sample.

From a clinical perspective, our study highlights the value of a more systemic approach to a clinical assessment and interpersonal framework for treatment. Partners in a long-term, committed relationship showed a wide range of subjective responses when their male partner has a sexual problem, although relationship satisfaction was found to be relatively high and resilient in the majority of couples in our survey. While both partners in couples with male sexual problems reported lower levels of sexual satisfaction than their counterparts without problems, this did not impact significantly on their relationship satisfaction for most couples. This study provides the first in-depth, assessment of these factors in long-term couples in stable partner relationships, taking into account perspectives of both male and female partners in the relationship.

Notes

The corresponding author may be contacted for further details about the questionnaire or to request a copy of the questionnaire.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Araujo, A. B., Hall, S. A., Ganz, P., Chiu, G. R., Rosen, R. C., Kupelian, V., & McKinlay, J. B. (2010). Does erectile dysfunction contribute to cardiovascular disease risk prediction beyond the Framingham risk score? Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 26, 350–356.

Birnbaum, G. E., Reis, H. T., Mikuliner, M., Gillath, O., & Orpaz, A. (2006). When sex is more than just sex: Attachment orientation, sexual experience, and relationship quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 929–943.

Butzer, B., & Campbell, L. (2008). Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15, 141–154.

Byers, E. S. (2005). Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long term relationship. Journal of Sex Research, 42, 113–118.

Chew, K. K., Finn, J., Stuckey, B., Gibson, N., Sanfilippo, F., Bremner, A., & Jamrozik, K. (2010). Erectile dysfunction as a predictor for subsequent atherosclerotic cardiovascular events: Findings from a linked-data study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7, 192–202.

Eardley, I., Fischer, W., Rosen, R. C., Niederberger, C., Nadel, A., & Sand, M. (2007). The multinational men’s attitudes to life events and sexuality study: The influence of diabetes on self-reported erectile function, attitudes and treatment-seeking patterns in men with erectile dysfunction. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 61, 1446–1453.

Fisher, W. A., Donahue, K., Long, J. S., Heiman, J. R., Rosen, R. C., & Sand, M. S. (2014). Individual and partner correlates of sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife couples: Dyadic analysis of the International Survey of Relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior,. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0426-8.

Fisher, W. A., Eardley, I., McCabe, M., & Sand, M. (2009a). Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a shared sexual concern of couples: Association of female partner characteristics with male partner ED treatment seeking and phosphodiestrerase type 5 inhibitor utilization. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6, 3111–3124.

Fisher, W. A., Eardley, I., McCabe, M., & Sand, M. (2009b). Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a shared concern of couples: I. Couple conceptions of ED. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6, 2746–2760.

Fisher, W., Rosen, R., Eardley, I., Niederberger, C., Nadel, A., Kaufman, J., & Sand, M. (2004a). The Multinational Men’s Attitudes to Life Events and Sexuality (MALES) Study II: Understanding PDE5 inhibitor treatment seeking patterns among men with erectile dysfunction. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 1, 146–156.

Fisher, W., Rosen, R., Eardley, I., Niederberger, C., Nadel, A., Kaufman, J., & Sand, M. (2004b). The Multinational Men’s Attitudes to Life Events and Sexuality (MALES) Study II: Understanding PDE5 inhibitor treatment seeking patterns among men with erectile dysfunction. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 1, 150–160.

Fisher, W. A., Rosen, R. C., Eardley, I., Sand, M., & Goldstein, I. (2005). Sexual experience of female partners of men with erectile dysfunction: The Female Experience of Men’s Attitudes to Life Events and Sexuality (FEMALES) study. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 2, 675–684.

Goldstein, I., Fisher, W. A., Sand, M., Rosen, R. C., Mollen, M., Brock, G., & Derogatis, L. R. (2005). Women’s sexual function improves when partners are administered Vardenafil for erectile dysfunction: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 2, 819–832.

Heiman, J. R., Long, S., Smith, S. J., Fisher, W. A., Sand, M., & Rosen, R. C. (2011). Satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife and older couples in five countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 741–753.

Heiman, J. R., Talley, D. R., Bailen, J. L., Rosenberg, S. J., Pace, C. R., & Bavendam, T. (2007). Sexual function and satisfaction in heterosexual couples when men are administered sildenafil citrate (Viagra) for erectile dysfunction: A multicentre, randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled trial. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 114, 437–447.

Inman, B. A., St. Sauver, J. L., Jacobson, D. J., McGree, M. E., Nehra, A., Lieber, M. M., … Jacobsen, S. J. (2009). A population-based longitudinal study of erectile dysfunction and future coronary artery disease. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 84, 108–113

Kupelian, V., Araujo, A. B., Chiu, G. R., Rosen, R. C., & McKinlay, J. B. (2010). Relative contributions of modifiable risk factors to erectile dysfunction: Results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Preventive Medicine, 50, 19–25.

Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., Glasser, D. B., Kang, J. H., Wang, T., Levinson, B., & Gingell, C. (2006). A cross-national study of subjective sexual well-being among older women and men: Findings from the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35, 145–161.

Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., & Rosen, R. C. (1999). Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. Journal of the American Medical Association, 281, 537–544.

Lindau, S. T., Schumm, L. P., Laumann, E. O., Levinson, W., O’Muircheartaigh, C. A., & Waite, L. J. (2007). A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 762–767.

Liu, C. (2003). Does quality of marital sex decline with duration? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 55–60.

Long, J. S., & Freese, J. (2005). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using strata. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Nicolosi, A., Laumann, E. O., Glasser, D. B., Brock, G., King, R., & Gingell, C. (2006). Sexual activity, sexual disorders and associated help-seeking behavior among mature adults in five anglophone countries from the Global Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors (GSSAB). Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 32, 331–342.

Porst, H., Montorsi, F., Rosen, R. C., Gaynor, L., Grupe, S., & Alexander, J. L. (2007). The premature ejaculation prevalence and attitudes (PEPA) survey: Prevalence, comorbidities, and professional help-seeking. European Urology, 51, 816–823.

Rosen, R. C., & Althof, S. (2008). Impact of premature ejaculation: The psychological, quality of life, and sexual relationship consequences. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5, 1296–1307.

Rosen, R., Brown, C., Heiman, J., Leiblum, S., Meston, C., Shabsigh, R., & D’Agostino, (2000). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 26, 191–208.

Rosen, R. C., Fisher, W., Eardley, I., Niederberger, C., Nadel, A., & Sand, M. (2004). The Multinational Men’s Attitudes to Life Events and Sexuality (MALES) Study: I. Prevalence of erectile dysfunction and related health concerns in the general population. Current Medical Research Opinion, 20, 607–617.

Rosen, R. C., Riley, A., Wagner, G., Osterloh, I. H., Kirkpatrick, J., & Mishra, A. (1997). The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology, 49, 822–830.

Rubin, H., & Campbell, L. (2012). Day-to-day changes in intimacy predict heightened relationship passion, sexual occurrence, and sexual satisfaction: A dyadic diary analysis. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3, 224–231.

Shifren, J. L., Monz, B. U., Russo, P. A., Segreti, A., & Johannes, C. B. (2008). Sexual problems and distress in United States women: Prevalence and correlates. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 112, 970–978.

Spanier, G. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family, 38, 15–28.

Travison, T. G., Sand, M. S., Rosen, R. C., Shabsigh, R., Eardley, I., & McKinlay, J. B. (2011). The natural progression and regression of erectile dysfunction: Follow-up results from the MMAS and MALES studies. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8, 1917–1924.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an independent investigator-initiated Grant from Bayer-Schering Inc. Sampling and data collection fieldwork were performed by Synovate Healthcare, Inc., The design, conceptualization, analysis, and interpretation of the results are the sole product of discussions among the co-authors, represent the consensus of the co-authors, and have not been subject to editorial revision by Bayer-Schering, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rosen, R.C., Heiman, J.R., Long, J.S. et al. Men with Sexual Problems and Their Partners: Findings from the International Survey of Relationships. Arch Sex Behav 45, 159–173 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0568-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0568-3