Abstract

The Cerrado Biome is the second largest in Brazil covering roughly 2 million km2, with varying features throughout its area. The Biome is endangered but it is also source of animal species for rural, green urban and degraded rainforest areas. Ticks are among Cerrado species that establish at anthropogenic sites and although information about them is steadily increasing, several features are unknown. We herein report tick species, abundance and some ecological relationships within natural areas of the Cerrado at higher altitudes (800–1500 m) within and around Serra da Canastra National Park, in Minas Gerais State Brazil. In total of 1196 ticks were collected in the environment along 10 campaigns held in 3 years (2007–2009). Amblyomma sculptum was the most numerous species followed by Amblyomma dubitatum and Amblyomma brasiliense. Distribution of these species was very uneven and an established population of A. brasiliense in the Cerrado is reported for the first time. Other tick species (Amblyomma ovale, Amblyomma nodosum, Amblyomma parvum, Ixodes schulzei and Haemaphysalis leporispalustris) were found in lesser numbers. Domestic animals displayed tick infestations of both rural and urban origin as well as from natural areas (Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato, Rhipicephalus microplus, Dermacentor nitens, A. sculptum, A. ovale, Amblyomma tigrinum, Argas miniatus). Amblyomma sculptum had the widest domestic host spectrum among all tick species. DNA of only one Rickettsia species, R. bellii, was found in an A. dubitatum tick. Several biological and ecological features of ticks of the studied areas are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Cerrado Biome is roughly located in southeast and central Brazil and covers about 2 million km2, representing ca. 22% of the territory of Brazil with small areas extending into Bolivia and Paraguay (Oliveira-Filho and Ratter 2002). The Biome exhibits a mosaic of physiognomies, from grasslands to forests. Between these two extremes lies a continuum of savanna formations spanning the entire range of woody plant density, referred to collectively as the cerrados (Oliveira-Filho and Marquis 2002). At several sites the Cerrado is intermingled with neighboring Biomes such as Atlantic rainforest, Amazon, and Caatinga (dry lands with unevenly distributed rainfalls). The Cerrado is very adequate for agro-industrial activities and the whole Biome is endangered by human activities. At the same time, reinstatement of rainforests and riparian forests and establishment, within urban settings, of green leisure and sport areas create an environment similar in several aspects to the Cerrado. These new areas are prone to colonization by several species that live in the Cerrado. An extreme example of a Cerrado animal flourishing within urban and peri-urban settings is the tick Amblyomma sculptum, a member of the Amblyomma cajennense species complex (Nava et al. 2014). This tick species is commonly found in relatively small green areas at anthropogenic sites (Queirogas et al. 2012) and in a few locations is the vector of Rickettsia rickettsii, the highly lethal Brazilian spotted-fever agent (Labruna 2009; Szabó et al. 2013a).

Recognition of species and their abundance, natural ecological relationships and patterns in original settings may be of great value to understand unbalanced situations within anthropized areas. Despite the several studies of tick populations within the Cerrado Biome during the last two decades (Bechara et al. 2002; Campos Pereira et al. 2000; Knight 1992; Martins et al. 2011, 2015; Szabó et al. 2007a; Veronez et al. 2010), information is still scarce, and many features of the Biome were not addressed. The huge extension of the Cerrado and the variable influence of the neighboring Biomes certainly allows for a certain amount of variations within the Biome. Considering the importance of ticks as hazards for both public and animal health and lack of knowledge on several aspects of species distribution and ecological relationships we herein report tick species and features of this parasite's abundance, ecological relationships and seasonality within natural areas of the Serra da Canastra National Park as well as neighboring private owned natural areas. This park has as characteristic features sloping plateaus, ranging from 800 to 1500 m of elevation, rocky open grasslands, occasional forest patches and a rich biodiversity. Previous reports from the Park are restricted to ticks collected from Xenarthra and Carnivora (Arrais 2013; Botelho et al. 1989; Martins et al. 2015) none of which addressed ticks free living in the environment, ecological or seasonal aspects.

Materials and methods

Study site

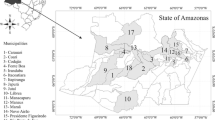

This study was conducted from April 2007 to November 2009 in the Serra da Canastra National Park and in natural areas from neighboring properties. Serra da Canastra National Park is within the Cerrado domain, in the southwestern part of the Minas Gerais State in Brazil (20°20′S–46°40′W). It has an area of 198,000 ha, and is characterized by sloping plateaus, from 800 to 1500 m high. According to Köppen’s system the climate of the region is Cwb, with a dry and cool season from April to September, with (mean temperature of 17 °C), and a wet and hot season from October to March (mean temperature of 22 °C). Annual precipitation ranges from 1300 to 1700 mm. Tick sampling occurred at eight locations of diverse phytophysiognomies, four within the park and at higher altitude (above 1300 m) and four in natural areas in neighboring private properties (Table 1) with altitudes ranging from 823 to 912 m.

Tick sampling in the environment

Ten tick collection campaigns were led in locations 1–7 from April 2007 to November 2009 (Table 1). Location eight refers to a farm where only animal sampling was conducted. To evaluate tick seasonal activity, campaigns occurred at each of eight consecutive seasons from March 2008 onwards. Cloth dragging, CO2 traps and visual search on vegetation were used for tick sampling as described before (Terassini et al. 2010; Veronez et al. 2010). Briefly, ticks were collected in each location and sampling campaign using 20 CO2 traps and dragging for 60 min with white 2-m-long and 1-m-wide flannels. Visual search was performed at distances of approximately 400 m just before dragging and only in forestall phytophysiognomies exhibiting evident trails (sites 5 and 6). Adult and nymphal ticks were counted individually whereas each larval cluster was considered a unit.

Domestic animal sampling

Domestic animals from four private properties (farms/ranches) bordering the park (sites 5–8) and occasionally stray dogs were examined for ticks by convenience at each campaign. A few animals, mainly dogs, were examined repeatedly along the several campaigns but never twice in the same campaign. Each animal was examined by two researchers for 3–5 min. Whenever infestations were too high (usually bovines and horses), only a sample of ticks was collected.

Tick identification

Collected ticks were stored in alcohol but engorged larvae and nymphs were kept alive in laboratory at 27 °C and 85% UR until molting to the next stage and identified based on reference bibliography (Martins et al. 2010; Nava et al. 2014; Onofrio et al. 2006) and comparison with reference laboratory specimens. Lack of keys for Neotropical Amblyomma larvae as well as damaged samples precluded identification of some tick samples which were retained as Amblyomma sp. Seven larval batches were identified to species level by molecular methods. For this purpose, a sample from the larval batch was processed by DNA extraction, PCR, and partial DNA sequencing of the tick mitochondrial 16S rDNA gene, as previously described (Ogrzewalska et al. 2009a). Voucher tick specimens collected in the present study have been deposited at the CC-FAMEV/UFU Tick Collection, Federal University of Uberlândia (accession numbers: 259–263; 411–412; 440–443; 449–450; 471–476).

Rickettsia in ticks

DNA was extracted from a sample of 48 ticks (1 female Amblyomma dubitatum; 1 male Amblyomma brasiliense; 23 female and 15 male A. sculptum; 5 female Rhipicephalus microplus; 2 female and 2 male Rhipicephalus sanguineus mostly from dogs, equines but also from bovines and environment) using the guanidine isothiocyanate phenol technique (Sangioni et al. 2005). DNA was then tested for Rickettsia by three consecutive PCR protocols. Firstly, all samples were tested with primers CS-78 and CS-323, targeting a 401-bp fragment of the citrate synthase gene (gltA) that occurs in all Rickettsia species (Labruna et al. 2004). A sample yielding a visible amplicon of the expected size was then tested by a second PCR protocol with primers Rr190.70F and Rr190.701R, targeting a 632-bp fragment of the 190-kDa outer membrane protein gene (ompA) (Roux et al. 1996) that is present in the spotted fever group Rickettsia species. Those samples that yielded no product on the second PCR for Rickettsia were further submitted to a third protocol using primers specific for a 338-bp fragment of the R. bellii gltA gene (Szabó et al. 2013b). All samples lacking visible product in any PCR targeting Rickettsia genes were tested for tick mitochondrial 16S rDNA gene to control for DNA extraction failure. The only PCR Rickettsia product was sequenced and submitted to BLAST analysis, to determine its similarities to the relevant sequences from identified Rickettsia species (Altschul et al. 1990).

Data analysis

Quantitative descriptors of tick populations were used according to Bush et al. (1997).

Ethics and permits

All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use/CEUA of the Federal University of Uberlândia (Protocol No 007/08) and Brazilian Environment Institute—IBAMA (Permit No 11398-1).

Results

Tick numbers and species

Ticks from the environment: A total of 1196 ticks belonging to three genera and eight species were collected along 10 campaigns held in 3 years (2007–2009). Amblyomma sculptum was the most numerous species (576 adults, 272 nymphs and 2 larval batches, 71.6% of the total) followed by A. dubitatum (140 adults and 33 nymphs, 14.5% of the total) and A. brasiliense (131 adults, 30 nymphs and 2 larval batches, 13.6% of the total). Other tick species were much less numerous; Amblyomma ovale (4 adults, 0.3%); Amblyomma nodosum (2 adults and 1 nymph, 0.3%); Amblyomma parvum (1 nymph, 0.1%); Ixodes schulzei (1 larval batch, 0.1%), and Haemaphysalis leporispalustris (1 larval batch, 0.1%). Additionally, 64 nymphs and 20 larval batches were retained as Amblyomma spp.

The I. schulzei larval batch was identified by morphological comparison with laboratory-reared larvae derived from an engorged female collected in the state of São Paulo, as reported elsewhere (Labruna et al. 2003). The remaining larval pools were identified to species through molecular analysis. In these cases, 2 larval pools generated 16S rDNA identical fragments that were 99.7% (371/372-bp) identical to the GenBank sequence of A. sculptum (KY172626); 3 larval pools generated 16S rDNA identical fragments that were 99.8% (417/418-bp) identical to the GenBank sequence of A. brasiliense (KM519941); and 1 larval pool generated a 16S rDNA fragment that was 100% (382/382-bp) identical to the GenBank sequence of H. leporispalustris (KU096986). These 16S rDNA sequences generated in the present study have been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers MH114024 (A. sculptum), MH114023 (A. brasiliense) and MH114025 (H. leporispalustris).

Domestic animals

Out of 96 dog examinations, 51 yielded ticks (prevalence of 53.1%, mean infestation intensity of 3.3 ticks). Overall 169 ticks of five species were found; A. sculptum (6 adults, 73 nymphs and 1 larva, 47.3% of the total), R. sanguineus sensu lato (72 adults and 1 nymph, 43.2%), A. ovale (8 adults, 4.7%); R. microplus (6 adults and 1 nymph, 4.1%) and Amblyomma tigrinum (1 adult, 0.6%). Additionally, 55 nymphs and 21 larvae were retained as Amblyomma spp. On 17 bovine examinations, all animals were infested (prevalence of 100%) and two tick species found; R. microplus (185 adults and 15 nymphs) and A. sculptum (11 adults and 3 nymphs) as well as two Amblyomma sp. nymphs. Every examined horse (n = 16) was infested (prevalence of 100%) and three tick species were found; A. sculptum (136 adults, 11 nymphs and 8 larvae), Dermacentor nitens (29 adults and 9 nymphs) and R. microplus (48 adults and 3 nymphs) as well as four nymphs and eleven larvae retained as Amblyomma sp. On three pigs kept unrestrained in one of the properties 26 adult A. sculptum were found. Solely one cat was examined and one A. sculptum and four Amblyomma sp. larvae were found. Two chicken pens were also examined and in one of them 23 adults, 25 nymphs and 14 larvae of Argas miniatus were found.

Humans

During the field work accidental tick-bites of researchers were recorded as follows: four female, five male and two nymphs of A. sculptum as well as four Amblyomma spp. nymphs.

Seasonality

Analysis of seasonal occurrence of ticks in the environment is restricted to A. sculptum, A. brasiliense and A. dubitatum (Fig. 1), species found in numbers high enough for this purpose. A. sculptum adults peaked in both summers but with the peak in the second summer more prominent. Two A. sculptum nymphal peaks were observed, both in winter, the first being much more prominent. It is noteworthy that the biggest nymphal peak was followed by biggest adult peak. All four larval batches identified as A. sculptum were found in autumn; three in 2008 and one in 2009. No clear-cut seasonal activity could be depicted for both A. brasiliense and A. dubitatum nymphs and adults. A. brasiliense adults had a small peak in 2008 autumn and a bigger one in winter 2009 meanwhile nymphs peaked in winter 2008. A. dubitatum adults peaked in the winter of 2009 whereas nymphs remained in constantly low numbers along all studied period. Tick sampling of domestic animals set by convenience was improper for seasonal analysis; it is noteworthy, however, that all A. sculptum nymphs on dogs were found in winter (eight in 2007, 23 in 2008 and 42 in 2009) whereas R. sanguineus adults were collected from dogs in all 10 campaigns without a peak in infestations (data not shown).

Ecological relationships

A quite uneven distribution among the several locations was observed in tick numbers and species (Table 2). Among the three most numerous species in the environment A. sculptum was found in all locations; however, 51.5% were from location 6 and only 0.5% and 0.1% from locations 2 and 3. Overall A. sculptum represented 80.4% of all ticks collected outside the park at lower altitudes and 45.2% inside the park, at altitudes 404–583 m higher. Distribution of the other two more prevalent species, A. brasiliense and A. dubitatum were utterly uneven. The former was found mainly in location 5 (85.9% of all ticks from this species) and location 7 (11%) whereas the latter species was found overwhelmingly in location 4 with 93.1% of the ticks from this species. Locations 2 and 3 yielded the lowest number of ticks, with six and four ticks, respectively, found along the 3 years of research. One A. ovale and many of the A. brasiliense and A. sculptum adults but not a single A. dubitatum were found by visual search at the tip of leaves facing trails and always within forestall formations.

Rickettsia

One DNA sample from an A. dubitatum adult female collected as nymph in location 4 yielded visible amplicon in PCR targeting gltA, no product in the PCR for ompA, and visible product in the third protocol using primers specific of the R. bellii gltA gene. PCR product from the first gltA PCR was DNA sequenced, generating a 190-bp sequence that was 100% identical to a fragment of the gltA gene of R. bellii from GenBank (CP000087).

Discussion

Amblyomma sculptum was by far the most prevalent and widespread species in the environment as already observed at lower altitudes elsewhere in the Cerrado (Szabó et al. 2007a, b; Veronez et al. 2010). This taxon was recently reinstated as a valid species and separated from five others that all together compose the A. cajennense species complex (Nava et al. 2014). In fact, each species from the complex, even though very similar morphologically, seem to have distinct ecological preferences (Beati et al. 2013; Labruna 2018). Amblyomma sculptum but not the other species from the complex, has a strong association with the Brazilian Cerrado (Martins et al. 2016; Nava et al. 2014). Thus, unless otherwise stated, A. cajennense ticks collected in this Biome before the recognition of A. cajennense complex (Knight 1992; Szabó et al. 2007a; Veronez et al. 2010) should be regarded as A. sculptum.

Amblyomma sculptum was found in all sampled locations but its distribution was uneven with most individuals collected within gallery and montane forests at lower altitudes and under stronger anthropogenic pressure whereas it was almost absent from prairies and savannah on bare rockaries. This observation has no straightforward explanation because altitude and lower temperatures, phytophysiognomy, host species and abundance and anthropogenic factors may all have an influence on its distribution. In fact, up to our knowledge this is the first systematic study of this tick species at higher altitudes of the Cerrado and information should be compared to forthcoming information. Nevertheless, association of A. sculptum with forestall phytophysiognomies was observed before in both natural and anthropogenic sites (Ramos et al. 2014a; Souza et al. 2006; Veronez et al. 2010) and shows the importance of shadowed area within the Cerrado for this tick species. By being attracted to CO2 traps and questing on leaves along trails within forests A. sculptum exhibited both hunting and ambush host locating strategies as already noted (Ramos et al. 2017). This dual behavior certainly contributes to greater host finding success.

Two other tick species, A. dubitatum and A. brasiliense were found routinely along the study period. Amblyomma dubitatum was collected only in locations beside water fonts and among these, overwhelmingly at the source of the São Francisco River. Truly, this tick species was already associated with environment prone to flooding (Queirogas et al. 2012; Szabó et al. 2007b). Not coincidently, A. dubitatum has capybaras (Hydrochoerys hydrochaeris), a rodent with semi-aquatic habits as main hosts for all stages, although small mammals may also feed immatures (Coelho et al. 2016; Nava et al. 2010). Capybara scats and visual observation of one animal at the gallery forest patch by the São Francisco River source indicates that this host was maintaining the local tick population. At this location, several A. sculptum ticks were found as well, albeit in lesser numbers. Actually, association of these tick species and capybara populations close to water sources is common at anthropogenic sites (Brites-Neto et al. 2013; Queirogas et al. 2012; Souza et al. 2006). Nonetheless, proportion of each species may vary with A. dubitatum prevailing in flood-prone areas besides the water sources and A. sculptum a little further away, at drier areas (Queirogas et al. 2012; Szabó et al. 2007b). Under experimental settings both tick species may transmit R. rickettsii (Sakai et al. 2014; Soares et al. 2012) but A. dubitatum seems to be less aggressive to humans (Pajuaba Neto et al. 2018) and thus Brazilian spotted-fever is usually linked to A. sculptum bites.

Amblyomma brasiliense is a Neotropical tick associated with tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests (Guglielmone et al. 2014) found in Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay (Nava et al. 2007). It is rather associated with Atlantic rainforests in Brazil (Pinheiro et al. 2014; Sabatini et al. 2010; Silveira and Fonseca 2013; Szabó et al. 2009, 2013b). Records outside this Biome such as Amazon (Aragão 1936) and South Brazil (Corrêa 1954) are rare, usually restricted to one individual and thus must be viewed with caution. At the same time, several systematic tick studies in the Cerrado and Pantanal Biomes (Campos Pereira et al. 2000; Knight 1992; Martins et al. 2011, 2015; Ramos et al. 2014a, b; Saraiva et al. 2012; Sponchiado et al. 2015; Szabó et al. 2007a, b; Veronez et al. 2010) failed to find A. brasiliense. Therefore, our work is the first to record an established population in this Biome. It is noteworthy, however that A. brasiliense in our environmental sampling was found overwhelmingly in the more humid phytophysignomies within the Cerrado and those that closest resemble humid rainforests. This tick species has several hosts among Perissodactyla and Artiodactyla and is frequently associated to Tayassuidae (Aragão 1936). In fact, peccary group was reported in the location of higher incidence of the tick. Importantly, A. brasiliense is among the most aggressive tick species towards humans (Aragão 1936; Guglielmone et al. 2006a; Szabó et al. 2006) although pathogen transmission has not been recorded. It was a tick species that was commonly found at the tip of leaves along trails within forests and thus exhibited ambush strategy to access hosts.

Only four A. ovale adults were found in environment, all at lower altitudes and within gallery and montane forests. This tick is also a common species within lower altitude Atlantic rainforests among southeast Brazil. In such areas, it may be the most prevalent adult tick species questing for hosts on leaves and on dogs with access to the forest (Sabatini et al. 2010; Szabó et al. 2009, 2013b). Observations of Barbieri et al. (2015) showed that in Atlantic Rainforests of southeast Brazil A. ovale tends to be more numerous at altitudes below 700 m. Thus, forest fragments with altitudes around 900 m of the Cerrado in southeast Brazil seems to provide a borderline environment for this tick species and explains, at least partially, decreased tick numbers. Nonetheless public health importance of this tick in the Cerrado should be deeply investigated. In the Atlantic rainforest, A. ovale was shown to harbor and transmit Rickettsia parkeri strain Atlantic rainforest, a recognized human pathogen (Barbieri et al. 2014; Nieri-Bastos et al. 2016, 2018; Sabatini et al. 2010; Spolidorio et al. 2010; Szabó et al. 2013b).

Although only three A. nodosum adults were found in the environment, it is a common parasite species in the Cerrado. Adults parasitizes anteaters (Bechara et al. 2002; Campos Pereira et al. 2000; Martins et al. 2004, 2011) and nymphs are frequently the most prevalent species on passerine birds within this Biome (Luz et al. 2012; Pascoal et al. 2013; Ramos et al. 2015; Torga et al. 2013). Very likely this species exhibits a nidicolous or other host questing behavior for which our sampling methodology was inadequate. Immature stages of this species collected on wild birds have been found infected with R. parkeri strain NOD, yet of unknown pathogenicity for people (Nieri-Bastos et al. 2018; Ogrzewalska et al. 2009b).

Remaining tick species were represented by only one individual or single larval cluster, hampering ecological associations. In this regard finding a single specimen of A. parvum was surprising. Apart from its potential wide host array (Olegário et al. 2011), a broad analysis of its geographic distribution showed that this tick has a strong association with dry areas belonging to Chaco in Argentina and Paraguay, and Cerrado and Caatinga in Brazil (Nava et al. 2016). Since our sampling methodology was proven adequate for the species (Ramos et al. 2014a), higher numbers were expected. Thus, factors such as higher altitude and other undetermined ones may have interfered with the establishment of more numerous A. parvum populations in the study site.

Finding ticks from Ixodes genus solely once along several years of study was predictable. The richness and abundance of species of the Ixodes genus are higher in the Atlantic Forest and Amazon while in Cerrado, Chaco and Caatinga Biomes species of this genus are rarely recorded (Sponchiado et al. 2015). On the other hand, finding I. schulzei in the woodland location indicates the tropism of this tick to habitats with more dense vegetation cover, where it is likely to be associated with its main host species, the water rat Nectomys squamipes (Labruna et al. 2003; Saraiva et al. 2012). Collection of a larval cluster of H. leporispalustris in the environment also seems an incidental finding and it is usually collected on its habitual host, the wild rabbit Sylvilagus brasiliensis in Brazil (Labruna et al. 2000; Saraiva et al. 2012) but not during environmental samplings. It is a species of public health interest; it was shown to harbor under natural conditions and transmit under experimental settings, the bacterium R. rickettsii (Freitas et al. 2009; Fuentes et al. 1985; Parker et al. 1951).

Description of seasonal activity, attempted only for the three most abundant tick species, did not display a clear pattern for either A. brasiliense or A. dubitatum. This lack of pattern can be attributed to the overall low numbers and patchy distribution of ticks that is prone to stochastic variations. Amblyomma sculptum tick numbers varied intensely from 1 year to the other, nonetheless, grossly within a seasonal frame already described for the species (Labruna et al. 2002; Veronez et al. 2010) with adults prevailing around summer, nymphs in winter and larvae in autumn.

Domestic animal tick infestation did not present surprising features. Many animals harbored ticks from both wild and anthropized environment reflecting a dual exposure pattern. In this context, R. microplus, R. sanguineus lato sensu, D. nitens and A. miniatus are species strongly associated with, respectively, cattle, dogs, horses and chicken and their environment. Infestation of other animals with these species occurs when using environment infested by the aforementioned hosts (review by Guglielmone et al. 2006b).

Amblyomma sculptum was the species with broader distribution being found on all domestic animal species except in chickens. In a few instances, such infestations were reflecting merely exposure to a species highly prevalent in the environment, in others the domestic host may have contributed to A. sculptum tick populations. Observations under experimental and/or natural settings indicate that among domestic animals, horses and pigs are primary hosts for this tick species as well by feeding adults that will display adequate reproductive performance (Castagnolli et al. 2003; Labruna et al. 2001; Osava et al. 2016; Ramos et al. 2014b). Nymphs of A. sculptum seem to have an even larger array of adequate domestic hosts which includes horses, pigs, dogs and bovines (Castagnolli et al. 2003; Labruna et al. 2001; Osava et al. 2016; Ramos et al. 2014b, 2016; Szabó et al. 2001, 2007b). In fact, many engorged nymphs collected from all domestic animals in our survey successfully molted to adults in the laboratory. Clearly this tick species in the Cerrado is the one that poses the widest wild-domestic interface.

Other two tick species found, both on dogs, albeit in very low numbers display features of interest. Amblyomma ovale is a tick from wild carnivores (Labruna et al. 2005) and, as mentioned above, host seeks in humid forestall areas. Thus, dogs will be infested during access to wild areas/forests, a behavior that represents an important aspect for the Atlantic rainforest rickettsiosis (Szabó et al. 2013b) yet unknown in the Cerrado. Amblyomma tigrinum found once on a dog, is also a tick species that parasitizes carnivores during the adult stages (Labruna et al. 2005) whereas immature stages are found on small rodents and ground feeding birds (Nava et al. 2006). In fact, A. tigrinum was found on several carnivores captured in the same reserve of our survey (Arrais 2013; Martins et al. 2015) and was found in high prevalence and as the main tick species on manned wolves (Arrais 2013). In this regard, it is surprising that not a single tick from these species was collected during our environmental sampling along ten seasons, many times at locations known to be used by manned wolves.

Survey for Rickettsia yielded only one species but should be viewed as preliminary since analyzed tick sample was small. Rickettsia bellii, the only species found, is of unknown pathogenicity and should probably be viewed rather as a tick endosimbiont due to its high prevalence within tick populations and the wide array of species it colonizes without a perceptible damaging effect upon ticks (Labruna et al. 2007; Pacheco et al. 2009; Sakai et al. 2014). In this sense finding in A. dubitatum only expands its geographic range because it has been described from this tick species multiple times (Pacheco et al. 2009; Sakai et al. 2014).

In conclusion tick samplings, herein reported show that tick species distribution in the Cerrado is uneven, patchy, reflecting ecological preferences, host availability and other unknown factors. In this context, A. brasiliense, a tick rather related to Atlantic rainforest, is capable to establish in the Cerrado under peculiar conditions, probably with necessity for sites with enhanced humidity. A. sculptum on the other hand is a tick species that seems to be well adapted to an array of the Cerrado environments/phytophysignomies and thus it is more widespread within the Biome. Such favorable conditions seem to be replicated within green anthropized areas, allowing for the establishment of A. sculptum populations. Furthermore, its wide host array provides nourishment throughout several phytophysiognomies. Thus, it is not surprising that it is the main tick species to bite humans within this Biome both in natural but also in anthropized areas. Nonetheless, environment at higher altitudes, above 1300 m, seem to impact negatively upon this tick species and further observations should pinpoint factors that are responsible for such observation.

References

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410

Aragão HB (1936) Ixodidas brasileiros e de alguns paizes limítrofes. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 31:759–841

Arrais RC (2013) Ocorrência de patógenos transmitidos por carrapatos (Anaplasma spp. Babesia spp. Ehrlichia spp. Hepatozoon spp. e Rickettsia spp.) em lobos guará (Chrysocyon brachyurus) e cães domésticos na região do Parque Nacional da Serra da Canastra, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Dissertation, Universidade de São Paulo

Barbieri ARM, Moraes-Filho J, Nieri-Bastos FA, Souza JC Jr, Szabó MPJ, Labruna MB (2014) Epidemiology of Rickettsia sp. strain Atlantic rainforest in a spotted fever-endemic area of southern Brazil. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 5:848–853

Barbieri JM, da Rocha CMBM, Bruhn FRP, Cardoso DLC, Pinter A, Labruna MB (2015) Altitudinal Assessment of Amblyomma aureolatum and Amblyomma ovale (Acari: Ixodidae) vectors of spotted fever group rickettsiosis in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. J Med Entomol. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjv073

Beati L, Nava S, Burkman EJ, Barros-Battesti DM, Labruna MBL, Guglielmone AA, Cáceres AG, Guzmán-Cornejo CM, León R, Durden LA, Faccini JLH (2013) Amblyomma cajennense (Fabricius 1787) (Acari: Ixodidae) the Cayenne tick: phylogeography and evidence for allopatric speciation. BMC Evol Biol 13:267. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-13-267

Bechara GH, Szabó MPJ, Almeida Filho WV, Bechara JN, Pereira RJG, Garcia JE, Pereira MC (2002) Ticks associated with armadillo (Euphractus sexcinctus) and anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) of Emas National Park, State of Goias, Brazil. Ann N Y Acad Sci 969:290–293

Botelho JR, Linardi PM, Encarnação CD (1989) Interrelações entre Acari Ixodidae e hospedeiros Edentata da Serra da Canastra, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 84:61–64

Brites-Neto J, Nieri-Bastos FA, Brasil J, Duarte KM, Martins TF, Veríssimo CJ, Barbieri AR, Labruna MB (2013) Environmental infestation and rickettsial infection in ticks in an area endemic for Brazilian spotted fever. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 22:367–372

Bush AO, Lafferty KD, Lotz JM, Shostak AW (1997) Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms margolis et al revisited. J Parasitol 83:575–583

Campos Pereira M, Szabó MPJ, Bechara GH, Matushima ER, Duarte JMB, Rechav Y, Fielden L, Keirans JE (2000) Ticks on wild animals from the Pantanal region of Brazil. J Med Entomol 37:979–983

Castagnolli KC, Figueiredo LB, Santana DA, Castro MB, Romano MA, Szabó MPJ (2003) Acquired resistance of horses to Amblyomma cajennense (Fabricius 1787) ticks. Vet Parasitol 117:271–283

Coelho MG, Ramos VN, Limongi JE, Lemos ERS, Guterres A, Costa Neto SF, Rozental T, Bonvicino CR, D’Andrea PS, Moraes-Filho J, Labruna MB, Szabó MP (2016) Serologic evidence of the exposure of small mammals to spotted-fever Rickettsia and Rickettsia bellii in Minas Gerais, Brazil. J Infect Dev Ctries 10:275–282. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc7084

Corrêa O (1954) Carrapatos determinados no RG do Sul Biologia patologia e controle. Arq Inst Pesq Vet Desidério Finamor 1:35–40

Freitas HT, Faccini JLH, Labruna MB (2009) Experimental infection of the rabbit tick Haemaphysalis Leporispalustris with the Bacterium Rickettsia Rickettsii and comparative biology of infected and uninfected tick lineages. Exp Appl Acarol 47:321–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-008-9220-4

Fuentes L, Caldernón A, Hun L (1985) Isolation and identification of Rickettsia rickettsii from the rabbit tick (Haemaphysalis leporispalustris) in the Atlantic zone of Costa Rica. Am J Trop Med Hyg 34:564–567

Guglielmone AA, Beati L, Barros-Battesti DM, Labruna MB, Nava S, Venzal JM, Mangold AJ, Szabó MPJ, Martins JR, González-Acuña D, Estrada-Peña A (2006a) Ticks (Ixodidae) on humans in South America. Exp Appl Acarol 40:83–100

Guglielmone AA, Szabó MPJ, Martins JRS, Estrada-Peña A (2006b) Diversidade e importância de carrapatos na sanidade animal. In: Barros-Battesti DM, Arzua M, Bechara GH (eds) Carrapatos de Importância Médico-Veterinária da Região Neotropical: Um guia ilustrado para identificação de espécies. Vox/ICTTD-3/Butantan, São Paulo, pp 115–138

Guglielmone AA, Robbins RG, Apanaskevich DA, Petney TN, Estrada-Peña A, Horak IG (2014) The hard ticks of the world. Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7497-1

Knight JC (1992) Observations on potential tick vectors of human disease in the Cerrado region of central Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 25:145–146

Labruna MB (2009) Ecology of Rickettsia in South America. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1166:156–166

Labruna MB (2018) Comparative survival of the engorged stages of Amblyomma cajennense sensu stricto and Amblyomma sculptum under different laboratory conditions. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/jttbdis201803019

Labruna MB, Leite RC, Faccini JLH, Ferreira F (2000) Life cycle of the tick Haemaphysalis leporis-palustris (Acari: Ixodidae) under laboratory conditions. Exp Appl Acarol 24:683–694

Labruna MB, Kerber CE, Ferreira F, Faccini JLH, De Waal DT, Gennari SM (2001) Risk factors to tick infestations and their occurrence on horses in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 97:1–14

Labruna MB, Kasai N, Ferreira F, Faccini JLH, Gennari SM (2002) Seasonal dynamics of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) on horses in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 105:65–77

Labruna MB, Silva MJN, Oliveira MF, Barros-Battesti DM, Keirans JE (2003) New records and laboratory-rearing data for Ixodes schulzei (Acari: Ixodidae) in Brazil. J Med Entomol 40:116–118

Labruna MB, Whitworth T, Bouyer DH, McBride J, Camargo LM, Camargo E, Popov V, Walker DH (2004) Rickettsia bellii and Rickettsia amblyommii in Amblyomma ticks from the state of Rondonia Western Amazon, Brazil. J Med Entomol 41:1073–1081

Labruna MB, Jorge RSP, Sana DA, Jácomo ATA, Kashivakura CK, Furtado MM, Ferro C, Perez AS, Silveira L, Santos TS Jr, Marques SR, Morato RG, Nava A, Adania CH, Teixeira RHF, Gomes AAB, Conforti VA, Azevedo FCC, Prada CS, Silva JC, Batista AF, Marvulo MFV, Morato RLG, Alho CJR, Pinter A, Ferreira PM, Ferreira F, Barros-Battesti DM (2005) Ticks (Acari:Ixodidae) on wild carnivores in Brazil. Exp Appl Acarol 36:149–163

Labruna MB, Pacheco RC, Richtzenhain LJ, Szabó MPJ (2007) Isolation of Rickettsia rhipicephali and Rickettsia bellii from Haemaphysalis juxtakochi ticks in the State of São Paulo, Brazil. Appl Env Microbiol 73:869–873

Luz HR, Faccini JLH, Landulfo GA, Berto BP, Ferreira I (2012) Bird ticks in an area of the Cerrado of Minas Gerais State, southeast Brazil. Exp Appl Acarol 58:89–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-012-9572-7

Martins JR, Medri IM, Oliveira CM, Guglielmone AA (2004) Ocorrência de carrapatos em tamanduá-bandeira (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) e tamanduá-mirim (Tamanduá tetradactyla) na região do Pantanal Sul Mato-Grossense, Brasil. Cienc Rural 34:293–295

Martins TF, Onofrio VC, Barros-Battesti DM, Labruna MB (2010) Nymphs of the genus Amblyomma (Acari: Ixodidae) of Brazil: descriptions redescriptions and identification key. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 1:75–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/jttbdis2010030022

Martins TF, Furtado MM, Jácomo AT, Silveira L, Sollmann R, Tôrres NM, Labruna MB (2011) Ticks on free-living wild mammals in Emas National Park Goiás State, central Brazil. Syst Appl Acarol 16:201–206

Martins TF, Arrais RC, Rocha FL, Santos JP, May Júnior JA, Azevedo FC, de Paula RC, Morato RG, Rodrigues FHG, Labruna MB (2015) Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) on wild mammals in the Serra da Canastra National Park and surrounding areas Minas Gerais, Brazil. Cienc Rural 45:288–291. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-8478cr20140734

Martins TF, Barbieri AR, Costa FB, Terassini FA, Camargo LM, Peterka CR, Pacheco RC, Dias RA, Nunes PH, Marcili A, Scofield A, Campos AK, Horta MC, Guilloux AG, Benatti HR, Ramirez DG, Barros-Battesti DM, Labruna MB (2016) Geographical distribution of Amblyomma cajennense (sensu lato) ticks (Parasitiformes: Ixodidae) in Brazil with description of the nymph of A. cajennense (sensu stricto). Parasit Vectors 9:186. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1460-2

Nava S, Mangold AJ, Guglielmone AA (2006) The natural hosts of larvae and nymphs of Amblyomma tigrinum. Vet Parasitol 140:124–132

Nava S, Lareschi M, Rebollo C, Benítez Usher C, Beati L, Robbins RG, Durden LA, Mangold AJ, Guglielmone AA (2007) The ticks (Acari: Ixodida: Argasidae Ixodidae) of Paraguay. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 101:255–270

Nava S, Venzal JM, Labruna MB, Mastropaolo M, Gonzáles EM, Mangold AJ, Guglielmone AA (2010) Hosts distribution and genetic diveregence (16S rDNA) of Amblyomma dubitatum (Acari: Ixodidae). Exp Appl Acarol 51:335–351

Nava S, Beati L, Labruna MB, Cáceres AG, Mangold AJ, Guglielmone AA (2014) Reassessment of the taxonomic status of Amblyomma cajennense (Fabricius 1787) with the description of three new species Amblyomma tonelliae n sp. Amblyomma interandinum n sp. and Amblyomma patinoi n sp. and reinstatement of Amblyomma mixtum Koch 1844 and Amblyomma sculptum Berlese 1888 (Ixodida: Ixodidae). Ticks Tick Borne Dis 5:252–276

Nava S, Gerardi M, Szabó MPJ, Mastropaolo M, Martins TF, Labruna MB, Beati L, Estrada-Peña A, Guglielmone AA (2016) Different lines of evidence used to delimit species in ticks: a study of the South American populations of Amblyomma parvum (Acari: Ixodidae). Ticks Tick Borne Dis 7:1168–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/jttbdis201608001

Nieri-Bastos FA, Horta MC, Barros-Battesti DM, Moraes-Filho J, Ramirez DG, Martins TF, Labruna MB (2016) Isolation of the pathogen Rickettsia sp. strain Atlantic rainforest from its presumed tick vector Amblyomma ovale (Acari: Ixodidae) from two areas of Brazil. J Med Entomol 53:977–981. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjw062

Nieri-Bastos FA, Marcili A, De Sousa R, Paddock CD, Labruna MB (2018) Phylogenetic evidence for the existence of multiple strains of Rickettsia parkeri in the New World. Appl Environ Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM02872-17

Ogrzewalska M, Pacheco RC, Uezu A, Richtzenhain LJ, Ferreira F, Labruna MB (2009a) Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting birds in an Atlantic rain forest region of Brazil. J Med Entomol 46:1225–1229. https://doi.org/10.1603/0330460534

Ogrzewalska M, Pacheco RC, Uezu A, Richtzenhain LJ, Ferreira F, Labruna MB (2009b) Rickettsial infection in Amblyomma nodosum ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) from Brazil. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 103:413–425

Olegário MMM, Gerardi A, Tsuruta SA, Szabó MPJ (2011) Life cycle of the tick Amblyomma parvum Aragão 1908 (Acari: Ixodidae) and suitability of domestic hosts under laboratory conditions. Vet Parasitol 179:203–208

Oliveira-Filho AT, Marquis RJ (2002) Introduction: development of research in the cerrados. In: Oliveira PS, Marquis RJ (eds) The cerrados of Brazil: ecology and natural history of a neotropical savanna. Columbia University Press, New York, pp 1–10

Oliveira-Filho AT, Ratter JA (2002) Vegetation physiognomies and woody flora of the cerrado biome. In: Oliveira PS, Marquis RJ (eds) The cerrados of Brazil: ecology and natural history of a neotropical savanna. Columbia University Press, New York, pp 91–120

Onofrio VC, Labruna MB, Pinter A, Giacomin FG, Barros-Battesti DM (2006) Comentários e chaves para as espécies do gênero Amblyomma. In: Barros-Battesti DM, Arzua M, Bechara GH (eds) Carrapatos de importância médico-veterinária da Região Neotropical: um guia ilustrado para a identificação de espécies. Vox/ICTTD-3/Butantan, São Paulo, pp 53–113

Osava CF, Ramos VN, Rodrigues AC, Reis Neto HV, Martins MM (2016) Amblyomma sculptum (Amblyomma cajennense complex) tick population maintained solely by domestic pigs. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep 6:9–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/jvprsr201611002

Pacheco RC, Horta MC, Pinter A, Moraes-Filho J, Martins TF, Nardi MS, Souza SSAL, Souza CE, Szabó MPJ, Richtzenhain LJ, Labruna MB (2009) Pesquisa de Rickettsia spp. em carrapatos Amblyomma cajennense e Amblyomma dubitatum no Estado de São Paulo. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 42:351–353

Pajuaba Neto AA, Ramos VN, Martins MM, Osava CF, Pascoal JO, Suzin A, Yokosawa J, Szabó MPJ (2018) Influence of microhabitat use and behavior of Amblyomma sculptum and Amblyomma dubitatum nymphs (Acari: Ixodidae) on human risk for tick exposure with notes on rickettsia infection. Tick Tick Borne Dis 9:67–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/jttbdis201710007

Parker RR, Pickens EG, Lackman DB, Bell EJ, Thraikill FB (1951) Isolation and characterization of Rocky mountain spotted fever rickettsiae from the rabbit tick Haemaphysalis leporis-palustris Packard. Public Health Rep 66:455–463

Pascoal JO, Amorim MP, Martins MM, Melo C, Silva Júnior EL, Ogrzewalska M, Labruna MB, Szabó MPJ (2013) Carrapatos em aves de uma reserva do Cerrado na periferia de Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 22:46–52

Pinheiro MC, Lourenço EC, Patricio PMP, Sá-Húngaro IJB, Famadas KM (2014) Free-living ixodid ticks in an urban Atlantic Forest fragment state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Braz J Vet Parasitol 23:264–268. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014020

Queirogas VL, Del Claro K, Nascimento ART, Szabó MPJ (2012) Capybaras and ticks in the urban areas of Uberlândia Minas Gerais Brazil: ecological aspects for the epidemiology of tick-borne diseases. Exp Appl Acarol 57:75–82

Ramos VN, Osava CF, Piovezan U, Szabo MPJ (2014a) Complementary data on four methods for sampling free-living ticks in the Brazilian Pantanal. Braz J Vet Parasitol 23:516–521. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014091

Ramos VN, Piovezan U, Franco AHA, Osava CF, Herrera MH, Szabo MPJ (2014b) Feral pigs as hosts for Amblyomma sculptum (Acari: Ixodidae) populations in the Pantanal Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Exp Appl Acarol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-014-9832-9

Ramos DGS, Melo ALT, Martins TF, Alves AS, Pacheco TA, Pinto LB, Pinho JB, Labruna MB, Dutra V, Aguiar DM, Pacheco RC (2015) Rickettsial infection in ticks from wild birds from Cerrado and the Pantanal region of Mato Grosso midwestern Brazil. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 6:836–842. https://doi.org/10.1016/jttbdis201507013

Ramos VN, Piovezan U, Franco AHA, Rodrigues VS, Nava S, Szabó MPJ (2016) Nellore cattle (Bos indicus) and ticks within the Brazilian Pantanal: ecological relationships. Exp Appl Acarol 68:227–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-015-9991-3

Ramos VN, Osava CF, Piovezan U, Szabó MPJ (2017) Ambush behavior of the tick Amblyomma sculptum (Amblyomma cajennense complex) (Acari: Ixodidae) in the Brazilian Pantanal. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/jttbdis201702011

Roux V, Fournier PE, Raoult D (1996) Differentiation of spotted fever group rickettsiae by sequencing and analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphism of PCR-amplifed DNA of the gene encoding the protein rOmpA. J Clin Microbiol 34:2058–2065

Sabatini GS, Pinter A, Nieri-Bastos FA, Marcili A, Labruna MB (2010) Survey of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) and their Rickettsia in an Atlantic rain forest reserve in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. J Med Entomol 47:913–916. https://doi.org/10.1603/ME10073

Sakai RK, Costa FB, Ueno T, Ramirez DG, Soares JF, Fonseca AH, Labruna MB, Barros-Battesti DM (2014) Experimental infection with Rickettsia rickettsii in an Amblyomma dubitatum tick colony naturally infected by Rickettsia bellii. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 5:917–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/jttbdis201407003

Sangioni LA, Horta MC, Vianna MCB, Gennari SM, Soares RM, Galvão MAM, Schumaker TTS, Ferreira F, Vidotto O, Labruna MB (2005) Rickettsial infection in animals and Brazilian spotted fever endemicity. Emerg Infect Dis 11:255–270

Saraiva DG, Fournier GFSR, Martins TF, Leal KPG, Vieira FN, Câmara EMVC, Costa CG, Onofrio VC, Barros-Battesti DM, Guglielmone AA, Labruna MB (2012) Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) associated with small terrestrial mammals in the state of Minas Gerais southeastern, Brazil. Exp Appl Acarol 58:159–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-012-9570-9

Silveira AK, Fonseca AH (2013) Distribution diversity and seasonality of ticks in institutional environments with different human intervention degrees in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev Bras Med Vet 35:1–12

Soares JF, Soares HS, Barbieri AM, Labruna MB (2012) Experimental infection of the tick Amblyomma cajennense Cayenne tick with Rickettsia rickettsii the agent of Rocky Mountain spotted-fever. Med Vet Entomol 26:139–151

Souza SSAL, Souza CE, Neto EJR, Prado AP (2006) Dinâmica sazonal de carrapatos (Acari: Ixodidae) na mata ciliar de uma região endêmica para febre maculosa na região de Campinas, São Paulo, Brasil. Cienc Rural 36:887–891

Spolidorio MG, Labruna MB, Mantovani E, Brandão P, Richtzenhain LJ, Yoshinari NH (2010) Novel spotted fever group rickettsioses Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 16:521–523

Sponchiado J, Melo GR, Martins TF, Krawczak FS, Labruna MB, Cáceres NC (2015) Association patterns of ticks (Acari: Ixodida: Ixodidae Argasidae) of small mammals in Cerrado fragments western Brazil. Exp Appl Acarol 65:389–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-014-9877-9

Szabó MPJ, Cunha TM, Pinter A, Vicentini F (2001) Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) associated with domestic dogs in Franca region São Paulo, Brazil. Exp Appl Acarol 25:909–916

Szabó MPJ, Labruna MB, Castagnolli KC, Garcia MV, Pinter A, Veronez VA, Magalhães GM, Castro MB, Vogliotti A (2006) Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) parasitizing humans in an Atlantic rainforest reserve of Southeastern Brazil with notes on host suitability. Exp Appl Acarol 39:339–346

Szabó MPJ, Olegário MMM, Santos ALQ (2007a) Tick fauna from two locations in the Brazilian savannah. Exp Appl Acarol 43:73–84

Szabó MPJ, Castro MB, Ramos HGC, Garcia MV, Castagnolli KC, Pinter A, Veronez VA, Magalhães GM, Duarte JMB, Labruna MB (2007b) Species diversity and seasonality of free-living ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in the natural habitat of wild Marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus) in southeastern Brazil. Vet Parasitol 143:147–154

Szabó MPJ, Labruna MB, Garcia MV, Pinter A, Castagnolli KC, Pacheco RC, Castro MB, Veronez VA, Magalhães GM, Vogliotti A, Duarte JMB (2009) Ecological aspects of free-living ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) on animal trails in an Atlantic rainforest of southeastern Brazil. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 3:57–72

Szabó MPJ, Pinter A, Labruna MB (2013a) Ecology biology and distribution of spotted-fever tick vectors in Brazil. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3:27. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb201300027

Szabó MPJ, Nieri-Bastos FA, Spolidorio MG, Martins TF, Barbieri AM, Labruna MB (2013b) In vitro isolation from Amblyomma ovale (Acari: Ixodidae) and ecological aspects of the Atlantic rainforest Rickettsia the causative agent of a novel spotted fever rickettsiosis in Brazil. Parasitol. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182012002065

Terassini FA, Barbieri FS, Albuquerque S, Szabó MPJ, Camargo LMA, Labruna MB (2010) Comparison of two methods for collecting free-living ticks in the Amazonian forest. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 1:194–196

Torga K, Tolesano-Pascoli GV, Vasquez JB, Silva Júnior EL, Labruna MB, Martins TF, Ogrzewalska M, Szabó MPJ (2013) Ticks on birds from cerrado forest patches along the Uberabinha river in the Triângulo Mineiro region of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Cienc Rural 43:1852–1857

Veronez VA, Freitas BZ, Olegário MMM, Carvalho WM, Pascoli GVT, Thorga K, Garcia MV, Szabó MPJ (2010) Ticks (acari: ixodidae) within various phytophysiognomies of a cerrado reserve in Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Exp Appl Acarol 50:169–179

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge Jonas Moraes-Filho, Iara Silveira, Fernanda A. Nieri-Bastos, Diego Garcia Ramirez, Maria Ogrzewalska, William Mendes Carvalho, Guilherme Fazan Rossi, Marcus do Prado Amorim, Thaisa Reis dos Santos, Jamile de Oliveira Pascoal, Ana Claudia Lemos Gomes and Vera Lúcia de Queirogas for their help during tick collections in the field. Authors are also indebted to Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—CNPq (Academic Career Research Fellowship to M.P.J. Szabó and Labruna, M.B. and financial support/Grant Number 471737/2007-0).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Szabó, M.P.J., Martins, M.M., de Castro, M.B. et al. Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in the Serra da Canastra National Park in Minas Gerais, Brazil: species, abundance, ecological and seasonal aspects with notes on rickettsial infection. Exp Appl Acarol 76, 381–397 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-018-0300-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-018-0300-9