Abstract

The Cerrado is Brazil’s tropical savannah, which is arguably under greater threat than the Amazon rainforest. The Cerrado Biome of tropical South America covers about 2 million km2 and is considered a biodiversity hot spot which means that it is especially rich in endemic species and particularly threatened by human activities. The Cerrado is increasingly exposed to agricultural activities which enhance the likelihood of mixing parasites from rural, urban and wildlife areas. Information about ticks from the Cerrado biome is scarce. In this report tick species free-living, on domestic animals and on a few wild animals in two farms in the Cerrado biome (Nova Crixás and Araguapaz municipalities, Goiás State, Brazil) are described. Amblyomma cajennense was the first and Amblyomma parvum the second host-seeking tick species found. Only two other tick species were found free-living: one Amblyomma nodosum and three Amblyomma naponense nymphs. Cattle were infested with Boophilus microplus and A. cajennense. Buffalos were infested with B. microplus and A. parvum. Dogs were infested with A. cajennense, Amblyomma ovale, A. parvum and Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks. Anocentor nitens, B. microplus, A. cajennense, and A. parvum were found on horses. Amblyomma auricularium were found attached to nine-banded armadillos and Amblyomma rotundatum to red-footed tortoise, cururu toads and a rattlesnake. The latter was also infested with an adult A. cajennense. No tick was found on a goat, a tropical rat snake and a yellow armadillo. Among the observations the infestation of several domestic animals with A. parvum seems be the main feature. It suggests that this species might become a pest. However, the life cycle of A. parvum in nature, as well as its disease vectoring capacity, are largely unknown. It would be important to determine if it is a species expanding its geographic range by adaptation to new hosts or if it has been maintained in high numbers at definite locations by specific and still undetermined conditions. A higher prevalence of A. cajennense in most Brazilian biomes, with the exception of rainforests, was already shown before. Thus this species is favored by deforestation and is an important research target as it is the most common vector associated with the Brazilian spotted fever.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Cerrado is Brazil’s tropical savannah, which is arguably under greater threat than the Amazon rainforest (Marris 2005). Such biome is considered a biodiversity hot spot which means that it is especially rich in endemic species and particularly threatened by human activities (Cincotta 2000). The Cerrado Biome of tropical South America covers about 2 million km2, an area approximately the same as that of Western Europe, representing ca. 22% of the land surface of Brazil, plus small areas in eastern Bolivia and northwestern Paraguay (Oliveira-Filho and Ratter 2002). The Cerrado is increasingly exposed to agricultural activities which enhance the likelihood of mixing parasites from rural, urban and wildlife areas. At the same time, although knowledge of human tick-borne diseases in South America is still limited, several tick-borne pathogenic agents such as Rickettsia parkeri (Venzal et al. 2004; Silveira et al. 2005) and Ehrlichia chafeensis (Machado et al. 2006) were recently described in the continent. It is thus possible to suppose that human tick-borne diseases in this part of the world are not properly diagnosed, are emerging or both. Thus describing vector life cycle, host preferences and tick species distribution of South American ticks becomes an important issue. Information of ticks from the Cerrado biome is scarce if one considers its vastness; apart from a few reports (Knight et al. 1992; Campos Pereira et al. 2000; Bechara et al. 2002) no systematic study was undertaken. In this report tick species free-living in two locations of the Cerrado biome and on a few wild animals are described. Ticks affecting domestic animals in this biome are also reported so as to evaluate the possible exposure and adaptation of wildlife ticks to these hosts.

Material and methods

Study sites

Six tick collections were performed in two farms located, approximately 200 km apart in the Cerrado in Goiás State, central west Brazil. The initial three collections occurred in the Moenda do Lago farm (13° 42′ 55″ S; 50° 46′ 52″ W; 236 m of altitude at the seat of the farm) in Nova Crixás Municipality, São José dos Bandeirantes district. This farm has 875 hectares in which, approximately 60% of the natural vegetation is preserved. It roughly corresponds to ecological unit 5 according to a recent classification of the environmental and ecological diversity of the Cerrado region of Brazil (Silva et al. 2006) (Fig. 1). In this unit poorly-drained flatlands dominate the landscape (70–250 m altitude), with flooding savannas as the dominant vegetation, although in some areas they form mosaics with open forests and small plots of better-drained savanna. Water seasonality is very strong, with large areas being flooded during the rainy season and then becoming very dry during the dry season. The main economic activity of the farm was the commercial breeding of the giant South American turtle (Podocnemis expansa). But it also had 400 bovines, 25 water buffalos, 15 horses, 2 goats and eight mongrel dogs. The farm was sold and most of the animals were not at available during the last tick collection.

Spatial heterogeneity, land use and conservation in the Cerrado region of Brazil according to Silva et al. (2006)

Additional three tick collections were performed at the Moenda da Serra farm (15° 04′ 18″ S; 50° 25′ 03″ W; 336 m of altitude at the seat of the farm), in the Araguapaz Municipality. This farm has 960 hectares and also has 60% of its area preserved. It roughly corresponds to ecological unit 2A according to the aforementioned classification of the Cerrado region of Brazil (Fig. 1). This unit is a mosaic of rolling terrains, plains and hills in the west. The dominant native vegetation is a dense savanna, sometimes forming mosaics with open savanna and native grasslands. The main economic activity of the farm is the commercial breeding of giant South American turtle as well. But it also had 250 cattle, 9 water buffalos, 8 horses, and a non-determined number of mongrel dogs during the study period.

Climate in both farms is characteristic of the Cerrado Biome region with a rainy summer and a very strong dry winter. According to the farm personnel wild fauna of the farms included, apart from several birds, reptiles, amphibians and small rodents, the following animals (nomenclature by Reis et al 2006): tapir (Tapirus terrestris), marsh deer (Blastocerus diochotomus; only in the Moenda do Lago farm), capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), common rhea (Rhea americana), collared peccary (Pecari tajacu), white lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari), capuchin monkey (Cebus apella), cougar (Puma concolor), jaguar (Panthera onca), giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous) and armadillos, among others.

Tick sampling

Tick collections in the Moenda do Lago farm were performed from 9 to12 of October 2004 (spring), from 23 to 27 of March 2005 (autumn) and from 3 to7 of August 2005 (winter) and in the Moenda da Serra farm from 1 to 6 of November 2005 (spring), from 9 to12 of February 2006 (summer) and from 23 to 27 of May 2006 (autumn). Sampling included capture of free-living ticks, collection of ticks from domestic animals and from a few wild animals. Free-living ticks were captured using CO2 traps and cloth dragging. This was done in natural areas displaying wild animal activity signs and reached by vehicle, on foot, on horseback or by boat. CO2 traps were used as previously described (Oliveira et al. 2000). Dragging was performed as described by Rechav (1982) but slightly modified. Briefly, the drag was pulled for 30 minutes by each of two persons simultaneously in a random fashion at each sampling site. During this period the cloth was examined for ticks approximately every 50 meters of dragging.

Whenever possible, sampling of free-living ticks on each farm at each expedition occurred repeatedly at the same locations and with a similar number of CO2 traps (3 to 17) and dragging time. Free living tick sampling was not possible to perform in flooded areas during the rainy season. Details on tick sampling locations are presented on Table 1.

At each sampling expedition, a variable number of domestic animals were examined for tick infestations. Ticks were also collected from several wild animals available by chance (hunted by dogs, overrun by automobiles in the road within or leading to the farm, wandering by and easy to catch and handle).

Tick identification

Currently, it is impossible to perform a proper morphological taxonomic identification of the immature stages of the Amblyomma species from Brazil. Thus, the collected larvae and nymphs were brought alive to the laboratory at the Federal University of Uberlândia, where attempts to rear them until the adult stage were performed by feeding them on tick-bite naïve rabbits, as previously described (Labruna et al. 2002a). Adults obtained from the engorged nymphs were used for species identification of the former immature ticks. The voucher tick specimens collected in the present study have been deposited in the CNC-FMVZ/USP National Tick Collection, University of São Paulo, SP, Brazil (accession number: 939) and the CC-FAMEV/UFU Tick Collection, Federal University of Uberlândia (accession numbers: 1–53, 216–218, 231–236).

Results

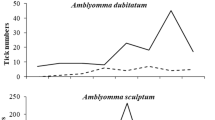

Identification and numbers of free living ticks collected in the Moenda do Lago farm, Nova Crixás and in Moenda da Serra farm, Araguapaz, are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Amblyomma cajennense was the main host-seeking tick species in both farms in all expeditions and in every phytophysiognomy. Adults of this species were found all over the year but were most numerous in the Moenda da Serra farm, particularly in the spring. Nymphs of A. cajennense were also found in every expedition with the exception of summer of 2006. Larvae of A. cajennense were found only in the winter (August, 2005) and autumn (May, 2006).

The second most numerous host-seeking species was Amblyomma parvum. Adults of this species were found in the Cerrado sensu stricto in the autumn of 2005 in Nova Crixás, whereas in Araguapaz it was found in higher numbers, particularly in the summer of 2006, in every searched phytophysiognomy and in all expeditions. Nymphs of this species were found only in Nova Crixás in August 2005 in an alluvial forest and in the Cerrado sensu stricto.

Only two other species were found host-seeking; nymphs of Amblyomma naponense in an alluvial forest and in the Cerrado sensu stricto (autumn, 2005) and one nymph of Amblyomma nodosum in the Cerrado sensu stricto (winter 2005), both in Nova Crixás. Several nymphs and two larva clusters could not be raised until the adult stage and were retained as Amblyomma sp.

Information on ticks found on domestic animals in Nova Crixás and Araguapaz, is presented in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. Cattle at both farms were highly infested and only tick samples could be collected. Boophilus microplus and A. cajennense were found on this host, the latter tick species only in Araguapaz. Buffalos were infested with B. microplus and in Araguapaz several A. parvum adults were found on this host as well. Dogs were infested with A. cajennense, Amblyomma ovale, A. parvum and Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks. R. sanguineus ticks were associated with higher infestations levels. They were found only in Araguapaz and on dogs that remained close to human dwellings. A. cajennense and A. parvum were found on dogs from both farms and A. ovale solely in Nova Crixás. All Amblyomma species on dogs were associated with hosts that were used to hunt and/or wander in the landscape. No tick was found on the only goat examined. Anocentor nitens, B. microplus, A. cajennense and A. parvum were the tick species found on horses. A. nitens was the main horse tick as it was found in every sampling and was responsible for high infestations levels particularly in the ear of the animals. All tick species were found on horses in both farms although A. cajennense and A. parvum were found in higher numbers in Araguapaz.

On wild animals two additional tick species were found (Table 6). Amblyomma auricularium adults were found attached to nine-banded armadillos and Amblyomma rotundatum was found on red-footed tortoise, on cururu toads and a rattlesnake. Two Amblyomma sp. nymphs were found on the cururu toads as well. The rattlesnake was also infested with an A. cajennense adult and two adults and one Amblyomma sp. nymph. These Amblyomma adults from this snake could not be properly identified because they were severely damaged. No tick was found on a tropical rat snake and a yellow armadillo.

Discussion

The predominance of A. cajennense at the study locations suggests an overall good adaptation for A. cajennense to the Cerrado biome. It is also a meaningful finding if one considers that this parasite is very aggressive to humans and the most common vector associated with the Brazilian spotted fever, caused by the bacterium Rickettsia rickettsii (Guedes et al. 2005; Sangioni et al. 2005; Guglielmone et al. 2006). In fact, the prevalence of A. cajennense over other tick species elsewhere in Brazil, with the exception of the rainforests, has been reported before (Campos Pereira et al. 2000; Labruna et al. 2002a; Estrada Peña et al. 2004; Labruna et al. 2005a; Szabó et al. 2007).

The establishment of A. cajennense seems to rely on the presence of at least one of its primary host species for the adult stage, considered to be tapirs, capybaras, or horses in Brazil (Labruna et al. 2001) and probably peccaries (Labruna et al. 2005a). However A. cajennense has a very broad host range being found on several mammals and also on birds (Aragão 1936, Rojas et al. 1999; Campos Pereira et al. 2000; Labruna et al. 2002a; Guglielmone et al. 2003a). Thus infestation of domestic animals in Nova Crixás and Araguapaz must be regarded as a common feature. On the other hand infestation of a rattlesnake with an adult A. cajennense has not been reported before and adds to its host species range. Actually, there are only two reports of A. cajennense on snakes in the Neotropics, one of nymphs and larvae on an undetermined snake species in Alto Apure, Apure, Venezuela (Fiasson 1949) and the other one of an undetermined A. cajennense stage on a captive Bothrops leucurus from Ilhéus, Bahia, Brazil (Encarnação et al. 2004).

Even though it was not the aim of this research and sampling did not cover all seasons, observations of the numbers of each Amblyomma instar at the various sampling periods indicate a roughly similar seasonal activity to the one-year generation pattern described for A. cajennense ticks in southeastern Brazil (Labruna et al. 2003). Such pattern, characterized by the highest activity of larvae during the autumn, of nymphs during the winter and of adults during the spring-summer months (Oliveira et al. 2000, Labruna et al. 2002b), shows that seasonality of A. cajennense ticks in central west Brazil may share similarities with the southeastern part of the country. This issue, however, must be further investigated.

Amblyomma parvum, the second most prevalent tick species found, is known to be very abundant in the Brazilian Pantanal region (Cançado et al. 2006) and common in northwest Argentina (Guglielmone et al. 1990). In fact, A. parvum has both a broad host and geographic range within the Neotropical region (Guglielmone et al. 2003a). Although the primary hosts for this tick species are unknown, the adults are frequently associated with carnivores (Labruna et al. 2005b) and those in immature stages with Caviidae rodents (Nava et al. 2006a). At the same time this tick species is also found on hosts as diverse as cattle (Guglielmone et al. 1990), long nosed-armadillo (Mullins et al. 2004), brown brocket deer (Campos Pereira et al. 2000), anteaters (Martins et al. 2004) and was shown to parasite humans as well (Guglielmone et al. 1991, 2006; Nava et al. 2006b). In this research such a broad host range was confirmed by the recovery of A. parvum from dogs, horses and buffalos but not from cattle. The infestation of bovines, however, cannot be ruled out because tick samples could only be taken from animals that were sometimes covered with several hundred or even thousands of B. microplus ticks.

The infestation of dogs and horses with A. parvum was significant since these hosts were found repeatedly infested during the survey. On one occasion in particular (March, 2005), a dog was found harboring many A. parvum ticks, including several engorging females. This animal had the habit of chasing small rodents in a nearby Cerrado (location 10), the probable source of the infestation. On the whole these observations indicate that dogs might be a suitable host for A. parvum adults.

Host-seeking A. parvum were found in several phytophysiognomies of the Cerrado but predominated in the drier areas since 73% of the free-living ticks of this species were found mostly in the Cerrado sensu stricto. These observations suggest that it is a very resistant tick species to desiccation and to high temperatures and might be favored by deforestation as is the case of A. cajennense (Estrada-Peña et al. 2004).

Considering the wide geographic distribution and the broad host range which includes domestic animals and man, A. parvum seems to have the potential to become a pest. The evaluation of such a parasitism is nevertheless complicated by the fact that A. parvum shares, on a gross inspection, common morphological features with unfed R. sanguineus; it is very tiny, brown and has a scutum that lacks ornamentation. Thus it is plausible to suppose that in Brazil dog infestations with A. parvum might be attributed to R. sanguineus. Moreover the life cycle and requirements of A. parvum in nature as well as its disease vectoring capacity are still poorly understood and thus this tick species deserves further research. It is chiefly important to determine if it is a species expanding its overall geographic range by adaptation to new hosts or if it is maintained in high numbers at definite locations by specific and still undetermined host and environmental conditions.

The other two free-living tick species, A. naponense and A. nodosum were found in very low numbers. A. naponense have been recorded chiefly on peccaries (P. tajacu and T. pecari), which are incriminated as the primary hosts (Labruna et al. 2005a). Peccaries are widespread in Brazil and it is possible to suppose that these were the local hosts for A. naponense. A. nodosum has been reported almost exclusively in anteaters (Guimarães et al. 2001) a host species that is also widely distributed in Brazil, particularly in the Cerrado region.

Several other tick species were found on animals. Those found on domestic animals were mostly the usual ones in Brazil. B. microplus is the cattle tick in the Neotropical region (Guglielmone et al. 2004) although other domestic and wild animals can be parasitized if sharing highly infested pastures (Labruna et al. 2002a, 2002b; Szabó et al. 2003). A. nitens and A. cajennense are the most frequent species infesting horses on farms of the state of São Paulo (Labruna et al. 2001, 2002b). Rhipicephalus sanguineus is the most common dog tick particularly in an urban environment and in rural areas it is responsible for high infestations if the animals are kept in kennels or restricted to human dwellings (Szabó et al. 2001; Labruna et al. 2005a). It must be emphasized, however, that the recent description of dissimilar populations of R. sanguineus ticks within South America (Szabó et al. 2005) has raised doubts regarding the biosystematic status of Neotropical R. sanguineus ticks and a reliable characterization of this species in the Neotropics is dependent on a more comprehensive study with samples from several locations of the region. Amblyomma ovale found on one dog is a very common tick of wild carnivores in Brazil (Labruna et al. 2005b) but it frequently parasitizes dogs from rural regions (Szabó et al. 2001; Labruna et al. 2005a) and has also been recorded on humans (Guglielmone et al. 2006; Szabó et al. 2006). Amblyomma ovale is not known to be a vector of any disease (Guglielmone et al. 2006).

Amblyomma auricularium and A. rotundatum collected on wild animals confirmed earlier observations. Amblyomma auricularium found on armadillos, its usual host (Guglielmone et al. 2003b), is a tick described in several South and Central American countries (Guglielmone et al. 2003a) but also in the United States (Lord and Day 2000). Amblyomma rotundatum found on tortoise and a snake is known to parasitize Amphibia and Reptilia and is widely distributed throughout the Neotropics as well (Guglielmone et al. 2003a).

An important feature of the results herein described is the partial dissociation observed between ticks species found on animals and those host-seeking in natural areas. Only A. cajennense and A. parvum were found on both animals and in the environment, whereas A. auricularium and A. rotundatum were found solely on wild animals. These hosts, however, were known to live in the areas sampled for free-living ticks. Such an observation indicates that the methods used for sampling free-living ticks had a bias and that several other tick species may be present in the studied area. Ticks might not have been attracted to the CO2 traps or were not host-seeking on the vegetation during dragging. Some of the species might also be nidicolous and should be found at particular sites such as burrows, and nests. Considering the difficulties to sample every possible ecological niche, the capture of wild animals is still the best option for a proper tick fauna sampling. However this is a laborious and difficult task due to the rich host fauna of the Cerrado and the necessity of many different capture methods.

Overall results from this work reassured existing information but also displayed worrying information on ticks from the Cerrado. The permissibility of this biome to ticks with such a broad host range as A. cajennense and A. parvum and coexistence at the same locations of wild and domestic hosts is above all a matter of concern. Considering the vastness of the Cerrado and the changes imposed by civilization, ticks as vectors should be closely monitored.

References

Aragão HB (1936) Ixodidas brasileiros e de alguns paizes limitrophes. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 31:759–841

Bechara GH, Szabó MPJ, Almeida Filho WV et al (2002) Ticks associated with Armadillo (Euphractus sexcinctus) and Anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) of Emas National Park, State of Goias, Brazil. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 969:290–293

Burgdorfer W 1970 Hemolymph test atechnique for detection of Rickettsiae in ticks. Am J Trop Med Hyg 19:1010–1014

Campos Pereira M, Szabó MPJ, Bechara GH et al (2000) Ticks on wild animals from the Pantanal region of Brazil. J Med Entomol 37:979–983

Cançado, PHD, Piranda, EM, Faccini, JLH (2006) Armadilha para capturar carrapatos utilizando uma fonte alternativa de CO2 para gelo seco In: Abstracts and program of the XIV Congresso Brasileiro de Parasitologia Veterinária & II Simpósio Latino-Americano de Rickettsioses, Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brazil, 3–6 September 2006

Cincotta RP, Wisnewski J, Engelman R (2000) Human populations in the biodiversity hotspots. Nature 404:990–992

Encarnação AMV, Santos WF, Montenegro IG et al (2004) Ocorrência de Babesia bigemina (Piroplasmida, Babesiidae) em Bothrops leucurus (Serpentes, Viperidae) em cativeiro. In: Abstracts and Program of the 25° Congresso Brasileiro de Zoologia, Brasilia, Brazil, 8–13 February 2004

Estrada-Peña A, Guglielmone AA, Mangold AJ (2004) The distribution preferences of the tick Amblyomma cajennense (Acari: Ixodidae), na ectoparasite of humans and other mammals in the Americas. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 98:283–292

Fiasson R (1949) Contribución al estudio de los ácaros de Venezuela. Rev Grancolombina Zoot Hig Med Vet 3:567–588

Gimenez DF (1964) Staining Ricckettsiae in yolk-sac cultures. Stain Technol 39:135–140

Guedes ERC, Leite MCA, Prata RC et al (2005) Detection of Rickettsia rickettsii in the tick Amblyomma cajennense in a new Brazilian spotted fever-endemic area in the state of Minas Gerais. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 100:841–845

Guglielmone AA, Mangold AJ, Aguirre DH et al (1990) Ecological aspects of four species of ticks found on cattle in Salta, Northwest Argentina. Vet Parasitol 35:93–101

Guglielmone AA, Mangold AJ, Vinabal AE (1991) Ticks (Ixodidae) parasitizing humans in four provinces of North-western Argentina. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 85:539–542

Guglielmone AA, Estrada-Peña A, Keirans JE, Robbins RG (2003a) Ticks (Acari: Ixodida) of the zoogeographic region. International Consortium on Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases (ICTTD-2), Atalanta, Houten, The Netherlands

Guglielmone AA, Estrada-Peña A, Luciani CA, et al (2003b) Hosts and distribution of Amblyomma auricularium (Conil, 1878) and Amblyomma pseudoconcolor Aragão, 1908 (Acari: Ixodidae). Exp Appl Acarol 29:131–139

Guglielmone AA, Bechara GH, Szabó MPJ, et al (2004) Ticks of importance for domestic animals in Latin America and Caribbean countries. Printed on CD by the International Consortium on Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases-2 of the European Comission INCO-DEV programme

Guglielmone AA, Beati L, Barros-Battesti DM et al (2006) Ticks (Ixodidae) on humans in South America. Exp Appl Acarol 40:83–100

Guimarães JH, Tucci CE, Barros-Battesti DM (2001) Ectoparasitos de Importância Veterinária. Editoras Plêiade/FAPESP, São Paulo

Knight JC (1992) Observations on potential tick vectors of human disease in the Cerrado region of central Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 25:145–146

Labruna MB, Kerber CE, Ferreira F et al (2001) Risk factors to tick infestations and their occurrence on horses in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 97:1–14

Labruna MB, de Paula CD, Lima TF et al (2002a) Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) on wild animals from the Porto-Primavera Hydroelectric Power Station Area, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 97: 1133–1136

Labruna MB, Kasai N, Ferreira F et al (2002b) Seasonal dynamics of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) on horses in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 105:65–77

Labruna MB, Amaku M, Metzner JA et al (2003) Larval behavioral diapause regulates life cycle of Amblymma cajennense (Acari: Ixodidae) in Southeast Brazil. J Med Entomol 40:170–178

Labruna MB, Camargo LM, Terrassini FA (2005a) Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) from the state of Rondônia, Western Amazon, Brazil. Syst Appl Acarol 10:17–32

Labruna MB, Jorge RSP, Sana DA et al (2005b) Ticks (Acari:Ixodidae) on wild carnivores in Brazil. Exp Appl Acarol 36:149–163

Lord C C, Day JF (2000) First record of Amblyomma auricularium (Acari: Ixodidae) in the United States. J Med Entomol 37:977–978

Machado RZ, Duarte JMB, Dagnone AS et al 2006 Detection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis in Brazilian Marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus). Vet Parasitol 139:262–266

Marris É (2005) The forgotten ecosystem. Nature 437:944–945

Martins JR, Medri IM, Oliveira CM et al (2004) Ocorrência de carrapatos em tamanduá-bandeira (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) e tamanduá-mirim (Tamanduá tetradactyla) na região do Pantanal Sul Mato-Grossense, Brasil. Cienc. Rural, Santa Maria 34:293–295

Mullins MC, Lazzarini SM, Picanço MCL et al (2004) Amblyomma parvum a parasite of Dasypus kappleri in the State of Amazonas, Brasil. Rev ciênc agrár 42:287–291

Nava S, Mangold AJ, Guglielmone AA (2006a) The natural hosts for larvae and nymphs of Amblyomma neumanni and Amblyomma parvum (Acari: Ixodidae). Exp Appl Acarol 40:123–131

Nava S, Caparros JA, Mangold AJ et al (2006b) Ticks (Acari: Ixodida: Argasidae, Ixodidae) infesting humans in Northwestern Cordoba Province, Argentina. Medicina 66:225–228

Oliveira-Filho AT, Ratter JA (2002) Vegetation physiognomies and woody flora of the Cerrado Biome. In: Oliveira PS, Marquis RJ (eds) The Cerrados of Brazil: ecology and natural history of a Neotropical savanna. Columbia University Press, New York, pp 91–120

Oliveira PR, Borges LMF, Lopes CML et al (2000) Population dynamics of the free-living stages of Amblyomma cajennense (Fabricius, 1787) (Acari: Ixodidae) on pastures of Pedro Leopoldo, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 92:295–301

Rechav Y (1982) Dynamics of tick populations in the Eastern Cape province of South-Africa. J Med Entomol 19:679–700

Reis NR, Peracchi AL, Pedro WA Lima IP (2006) Mamíferos do Brasil. Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina

Rojas R, Marini MA, Coutinho MTZ (1999) Wild birds as hosts of Amblyomma cajennense (Fabricius, 1787) (Acari: Ixodidae). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 94:315–322

Sangioni LA, Horta MC, Vianna MCB et al (2005) Rickettsial infection in animals and brazilian spotted fever endemicity. Emerg Infect Dis 11:255–270

Silva JF, Fariñas MR, Felfili JM et al (2006) Spatial heterogeneity, land use and conservation in the Cerrado region of Brazil. J Biogeogr 33:536–548

Silveira I, Pacheco RC, Szabó MPJ et al (2005) Isolamento de Rickettsia parkeri em cultura de células Vero a partir do carrapato Amblyomma triste In: Abstracts and Program of the XIX Congresso Brasileiro de Parasitologia, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 31 of October, 4 of November, 2005

Szabó MPJ, Cunha TM, Pinter A et al (2001) Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) associated with domestic dogs in Franca region, São Paulo, Brazil. Exp Appl Acarol 25:909–916

Szabó MPJ, Labruna MB, Pereira Campos M et al (2003) Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) on wild marsh-deer (Blastocerus dichotomus) from Southeast of Brazil: infestations prior and after habitat loss. J Med Entomol 40:268–274

Szabó MPJ, Mangold AJ, Carolina JF et al (2005) Biological and DNA evidence of two dissimilar populations of the Rhipicephalus sanguineus tick group (Acari: Ixodidae) in South America. Vet Parasitol 130:131–140

Szabó MPJ, Labruna MB, Castagnolli KC et al (2006) Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) parasitizing humans in an Atlantic rainforest reserve of Southeastern Brazil with notes on host suitability. Exp Appl Acarol 39:339–346

Szabó MPJ, Castro MB, Ramos HGC, et al (2007) Species diversity and seasonality of free-living ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) in the natural habitat of wild Marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus) in Southeastern Brazil. Vet Parasitol 143:147–154

Venzal JM, Portillo A, Estrada Peña A, Castro O et al (2004) Rickettsia parkeri in Amblyomma triste from Uruguay. Emerg Infect Dis 10:1493–1495

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank to José Roberto Ferreira Alves for the permission to collect tick on his farms and also for his assistance during the field work. We are also grateful to Marcos Valério Garcia and Viviane Aparecida Veronez for their collaboration during field work. This research was supported by the Federal University of Uberlândia and CNPq (Academic Career Research Fellowship to M.P.J.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Szabó, M.P.J., Olegário, M.M.M. & Santos, A.L.Q. Tick fauna from two locations in the Brazilian savannah. Exp Appl Acarol 43, 73–84 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-007-9096-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-007-9096-8