Abstract

Implementing environmental regulations in Pakistan remains an ideological thought with little or no enforcement. In this context, an organization’s sincerity towards corporate social responsibility initiatives is proven when it operates responsibly without regulatory pressures. Aimed at advancing the discourse on social identity and self-determination theories, this paper examines the influencing mechanism of multilevel responsible leadership on employees’ voluntary green behavior from a vertical perspective through leader identification and autonomous motivation for the environment. The sample included 357 employees working in 97 teams from pharmaceutical, cement manufacturing, and textile sector companies. Multi-source data were collected in two phases and analyzed with multilevel structural equation modeling through MPlus 8.3 software. The results support the hypothesized direct and mediating mechanisms of responsible leadership in shaping employees’ voluntary green behavior. Theoretical and managerial implications, limitations, and future research suggestions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Organizations contribute significantly to environmental degradation requiring investing substantial resources and special consideration to attain ecological sustainability (Andersson et al., 2013; Robertson & Barling, 2017). Responsible organizations actively pursue ecological initiatives through employees, being an essential resource for reaping sustainable advantages (Singh et al., 2020). However, employees’ indifference towards environmental initiatives has been a serious concern for organizations, which led to exploring a wide range of research avenues to understand better the facilitators of employees’ voluntary green behavior (VGB). Voluntary green behavior (VGB) comprises employee initiatives that exceed organizational expectations, including prioritizing environmental interests, initiating ecological programs and policies, lobbying and activism, and encouraging others to participate in similar actions (Norton et al., 2015), and aimed at realizing the organization’s environmental responsibility initiatives.

Research has acknowledged the vitality of organizational leadership as the key to opening employees’ minds toward responsible environmental concerns and shaping opinions about what to value the most (Faraz et al., 2021; Liao et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019). Scholarship has identified the influence of various leadership styles (Wang et al., 2018; Tuan, 2019) in shaping employees’ environmentally friendly behaviors under variable names such as voluntary green behavior, pro-environmental behavior, organizational citizenship behavior toward the environment, or extra-role behaviors toward the environment in developed countries. However, VGB, in the context of developing countries where the environmental legal framework is lacking, has garnered the least attention from scholars. More importantly, there is a paucity of research about responsible leadership in countries inherently lacking a rigorous environmental legal framework that could govern commercial activities for ecological impact (Kanwal, 2018). Environmental greening primarily depends on managers’ and employees’ self-initiative, where responsible leadership becomes crucial in promoting such green behavior (Lu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2021).

Responsible leadership represents “a social-relational and ethical phenomenon, which occurs in social interaction processes to achieve societal and environmental targets and objectives of sustainable value creation and positive value change” (Maak & Pless, 2006, p. 99). Compared to other value-based leadership styles, responsible leadership focuses on environmental and social objectives of sustainable value creation and positive change (Pless & Maak, 2011). Considering ecological sustainability is of primary consideration among responsible leaders (Ismail & Hilal, 2022), it is contended that responsible leadership in developing countries would proactively transform the subordinates into environmental citizens. However, exploring the influence of responsible leadership in predicting employees’ VGB has remained a neglected area of research in the context of developing countries such as Pakistan (Afsar et al., 2020; Miska & Mendenhall, 2018). Besides, it necessitates further need to explore the underlying factors linking responsible leadership and employees’ VGB.

Aimed at advancing the discourse on responsible leadership and employees’ VGB, this paper posits that in the absence of an appropriate system and environmental legal framework in developing countries, leader identification and autonomous motivation for the environment could be the critical underlying influencing mechanisms to cultivate employees’ VGB. This argument is in line with prior research contending that a particular leadership style may yield different employee outcomes in diverse contextual, cultural, and organizational settings (Afsar et al., 2020), and scholars have accentuated to explore further the underlying influencing processes of specific leadership styles on employee outcomes (Zhang et al., 2021).

Leader identification portrays that employees’ identity at the individual level overlaps to a certain extent with that of their leader (Walumbwa & Hartnell, 2011). Along the lines of social identity theory, employees experience a strong identification with leaders’ values, goals, and beliefs incorporated into the followers’ self-concept with high effectiveness. Such followers tend to internalize their manager’s concepts and seek an understanding of the leader’s expectations to find meaning in their work roles to identify themselves and their green behaviors. Moreover, such employees are inclined to adopt sustainable practices and own green principles following their leaders’ example (Zhao & Zhou, 2019). Therefore, we anticipate responsible leadership will influence employees’ VGB by inspiring and strengthening their leader identification.

Considering the complexity of employees’ engagement in voluntary behaviors, organization behavior scholars recommend employing a multi-theory perspective to unravel nuanced findings (Priyankara et al., 2018). In advancing this line of thinking, this paper additionally uses the self-determination theory (Gagné & Deci, 2005) to argue that autonomous motivation is considered one of the vital determinants of employees’ behavior in the workplace. In contrast to controlled motivation, autonomously motivated employees perform pleasing, agreeable, engaging, and inherently satisfying tasks. Employees’ VGB is an extra-role behavior, neither explicitly required from the employees nor compensated by the organizations, and needs to be internalized for permanence (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Therefore, considering the vitality of autonomous motivation for the environment in nurturing and sustaining employees’ VGB, it is argued that responsible leadership nurtures employees’ autonomous motivation for the environment (AME) to realize VGB.

This research offers several contributions to the literature on responsible leadership and employees’ VGB. First, this study provides a nuanced context of a developing country, i.e., Pakistan, which lacks a stringent environmental legal framework that could govern commercial activities for reduced environmental impact (Kanwal, 2018). In such countries, environmental greening initiatives are often left to employees’ free will, where leadership becomes crucial (Abubakar, 2020). Thus, in the context of a developing economy, exploring the influence of responsible leadership on employees’ VGB is highly valuable from academic and policy perspectives. Secondly, this study adds robustness from a methodological point of view on the relationship between responsible leadership and green behavior. Despite the call for research to employ the multilevel influence of leadership on employees’ VGB (Norton et al., 2017; Ying et al., 2020), empirical studies on responsible leadership and environmental behavior primarily rely on single-level analysis. This research is one of the rare attempts in this regard because it collected data from multiple respondents, nested in teams and at the firm level, and aggregated to the appropriate level for nuanced conclusions. However, during the literature review, only two studies were found to have used multilevel analysis, neither of which had VGB as an outcome variable (see Appendix Table 7). Thirdly, responsible leadership is a contextual factor, and the two mediators are individual factors that interact at higher and lower levels simultaneously, as against prior studies wherein only the individual or company level factors have been addressed, none of which is together between responsible leadership and VGB. Fourthly, the leadership scholarship suggests employing a multi-theory perspective to explore the underlying mechanisms of a specific leadership style in predicting employee outcomes (Ye et al., 2022; Ying et al., 2020). One theory does not necessarily explain a complete mechanism because theories do not apply in isolation in the real world. Therefore, this study employs social identity theory at a higher level and self-determination theory at a lower level construct.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Responsible leadership and employees’ voluntary green behavior

Responsible leadership focuses on responsibility issues, whether sustainable development, building trust, making morally correct decisions, or green action choices (Pless & Maak, 2011). In their earlier works, Maak and Pless (2006) opined that responsible leadership has been considered a leadership style wherein leaders serve as a thread weaving together the relationship between stakeholders while addressing the unaddressed theoretical gaps and taking up challenges in practical leadership. Accordingly, they defined responsible leadership as “a relational and ethical phenomenon that occurs in social processes of interaction with those who affect or are affected by leadership and have a stake in the purpose and vision of the leadership relationship” (p. 103). Voegtlin et al. (2019) further advanced this contention and maintained that “the consideration of stakeholders, both within and outside organizations, makes [responsible leadership] distinct from other approaches which frequently tend to focus on followers residing solely inside the organization.”(p.418). Considering this view, responsible leadership deems to have a broader scope with equally substantial applications toward the interests of external and internal stakeholders. Groves (2011) posits that this leadership style influences and propagates ideas among employees concerning corporate social responsibility and organizational citizenship.

Over the past decades, responsible leadership has been an increasingly studied leadership style and has proven its effectiveness on various employee-related outcomes (Miska & Mendenhall, 2018), including employees’ behaviors toward the environment. This study adds to the empirical evidence on the influence of responsible leadership on employees’ VGB in the context of developing countries lacking a stringent environmental legal framework that could govern commercial activities, which has not received much attention in the literature. Without an environmental legal framework, responsible leadership in the organization would be critical for setting employees’ focus toward a common goal of promoting sustainable green practices and achieving corporate social responsibility targets.

Employees’ VGB refers to the employees’ discretionary actions that contribute to the environment’s sustainability, and such behaviors are often not rewarded or required by the organization’s formal reward system (Yuriev et al., 2018). Such employee behaviors supplement the efforts to enhance the pro-environmental lifestyle of citizens and support the green strategic initiatives of an enterprise (Daily et al., 2009). These behaviors are visible in daily routines, for example, using less paper, helping coworkers adopt green behavior, recommending new ideas towards a pro-environmental workplace climate, and reducing energy consumption. Norton et al. (2015) clarified that the concept of VGB aligns closely with the notions of pro-environmental behaviors or organizational citizenship behavior for the environment.

Responsible leadership is central to internal and external and external stakeholder relationship-building and networking activities for the stakeholders (Maak & Pless, 2006). It aims to build sustainable positive relationships while catering to the four aspects, i.e., protecting interests, acquiring resources, connecting stakeholders, and understanding needs (Andersson et al., 2013; Pless, 2007; Wang et al., 2018). Responsible leadership creates a platform that facilitates mutual dialogue among all the stakeholders and ensures balance among everyone’s interests (Liao & Zhang, 2020). It lays a wholesome focus on the environment and society to add sustainable value (Pless & Maak, 2011). A responsible leader considers multiple parties’ interests in the business; they can interact timely for accurate information exchange and share their opinion with employees. Responsible leadership inspires by developing a code of conduct at the formal level and measures to manage initiatives related to environmental protection. Such codes of conduct clarify the differences between acceptable and unacceptable behaviors (Stahl & Luque, 2014). Employees’ VGB indicates an individual’s ethical beliefs and efforts to minimize the human footprint on the environment. It attempts to balance society and nature and contribute to sustainability, consistent with underlying principles of responsible leadership. In light of this discussion, the following is hypothesized:

H-1

Responsible leadership positively relates to employees’ voluntary green behavior.

Mediating role of leader identification

Social identity theory (Ashforth & Mael, 1989) postulates that identification means processes by which individuals form a psychological connection to an object referred to as a target. This target can include an organization, a coworker, a leader, or an occupation (Gumusluoglu et al., 2017). Leader identification entails how a subordinate emulates and learns from his/her leader, depending on the high level of such identification with the leader (Guo et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2015). Social behaviors are highly evocative when studied through social identity theory. Kim et al. (2014) argue that individual differences and social dynamics influence VGB and that there are implications linked with the relationships that guide behavior. Responsible leadership style and leader identification are such factors that guide employee behavior.

Wang et al. (2021) argue in favor of this logic that when managers focus on initiatives related to the sustainability contributions of a firm, it becomes exemplary behavior for followers. The environmentally responsible behavior of managers reinforces the organization’s focus on green behaviors, leaving an imprint on employee perceptions. They copy such practices while identifying themselves with their leaders and start following sustainable principles in the short run, which form part of the long-run plans. Due to an employee’s enhanced sensitivity toward leadership practices and expectations, leader identification increases the leader’s influence. Responsible leaders transform the traditional leadership models from a generic dyadic leader-follower model into a leader-stakeholder relationship (Pless, 2007). As a critical stakeholder, responsible leadership takes employees seriously and influences employee self-concepts such as personal identification.

Responsible leadership is characterized by long-term perspectives, CSR consciousness, and a global view (Zhao & Zhou, 2019), and for this reason, this leadership style bears a unique charm for subordinates. Employees try to emulate a supervisor when displaying characteristics that deem them responsible leaders. Previous studies have theoretically and empirically shown similar findings (Zhang et al., 2021; Zhao & Zhou, 2019). This study also uses ‘leader identification’ as an indication of what extent an individual identifies with his/her leader to emulate pious behavior like VGB. A responsible leader becomes a source of encouragement for employees such that they own and share their beliefs, norms, and goals, eventually incorporating their leader as an indispensable part of their self-identity (van Knippenberg et al., 2004).

Under the premise of social identity theory (Ashforth & Mael, 1989), subordinates are likely to act on behalf of the leader when experiencing higher leader identification because of a shared similarity in their interests which leads subordinates to shape their beliefs and perspectives according to their leader. Subordinates are inspired to copy and emulate their leader’s values and vision while defining their personal and job roles. An example of this line argument is that there is a higher likelihood that subordinates shall volunteer an extra-role behavior above and beyond the call of duty, such as VGB.

Responsible leaders show commitment in articulating a promising vision and pay greater attention to their subordinates’ needs. For example, responsible leaders are willing to make humanized decisions, care about employee benefits and seek mutually beneficial solutions (Pless, 2007). These measures express leaders’ concerns and attract employee sympathy while increasing their sense of higher purpose. Employees identify more with leaders when their needs are satisfied (van Knippenberg et al., 2004). Under these circumstances, responsible leadership can increase employee-leader identification.

In the presence of these characteristics, this emulation process and mimicking the responsible leaders helps subordinates establish a psychological connection with them. The leaders would then inspire associates to share their values, goals, and norms, and employees will incorporate these ideals of the leader into their own beliefs and values as an essential part of self-identity. The greater the intensity of this leader identification, the greater the subordinates’ willingness to follow a leader’s preferred lifestyle. This shared interest with the leader motivates the employee to embrace the leader’s perspectives as their own and work to mold their job roles towards the leader’s vision. Leader identification stimulates and amplifies employees’ commitment to fulfilling the expectations of responsible leaders. Empirical evidence has also found positive results where leader identification was explored as a mediator between responsible leadership and OCBE (Zhao & Zhou, 2019). In the same vein, we hypothesize the following:

H-2

Leader Identification positively mediates the influence of responsible leadership on employees’ VGB.

Mediating mechanism of autonomous motivation for environment

The basic premise of self-determination theory (SDT) asserts that different people have different kinds of motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Such motivation also varies between individuals. Considering its vitality in shaping and sustaining employees’ positive behavior, this study focuses on autonomous motivation, a mental process that stems from self-determination (Priyankara et al., 2018) driven by an inner consciousness. Although environmental behaviors are not inherently intrinsic, responsible leaders may induce an internalization process that transforms these motivations into the employees’ lifestyle choices (Osbaldiston & Sheldon, 2003). Extrinsically driven behaviors take time to convert into self-determined actions after undergoing an internalization process wherein values, attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs are initially acted upon for purely extrinsic reasons and become an integral part of an individual’s self (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Empirical findings also support the contemplation that autonomous motivation for the environment has been investigated as a predictor of OCBE and a mediator in the relationship between responsible leadership and OCBE (Norton et al., 2015; Priyankara et al., 2018). Autonomous motivation accentuates that an individual pursues those actions that are concordant and consistent with the underlying self (Kaplan & Madjar, 2015). SDT highlights that an individual’s autonomous motivation consists of identified, integrated, and intrinsic motivation. Under identified motivation, an individual performs actions consistent with his/her goals and values. Within integrated motivation, “people have a full sense that the behavior is an integral part of who they are, that it emanates from their sense of self and is thus self-determined” (Gagné & Deci, 2005). The last component of autonomous motivation is intrinsic motivation, wherein people perform those actions that are inherently exciting or pleasing.

Responsible leadership’s support for environmental and green behaviors enlarges employees’ sense of autonomy in acting more friendly towards the environment and nourishing autonomous motivation for the environment, which is one of the underlying mechanisms responsible leadership positively influences employees’ VGB. The primary concern of employees engaging in green behaviors is to seek self-satisfaction, which is how they reward, promote, and encourage pro-environmental behavior. Whether or not there are extrinsic rewards, an individual would still volunteer to participate in green initiatives because of autonomous motivation (Osbaldiston & Sheldon, 2003). Like internalizing the values synonymous with responsible leadership, employees align themselves with the leader’s values, thus enhancing autonomous motivation for the environment and promoting the employee to undertake VGB. It can be argued that people with autonomous motivation experience self-endorsement through voluntary acts for the self and inner desire. It triggers environmental improvement activities because they are consistent with individuals’ values and beliefs, or, as Deci and Ryan (2000) refer, a volition of their actions. Therefore, the following is hypothesized:

H-3

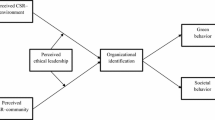

Autonomous motivation for the environment positively mediates the influence of responsible leadership on employees’ VGB. The research model of this study is presented in Figure 1.

Methodology

Sample and procedure

The sample comprised respondents working in organizations from the pharmaceutical, cement manufacturing, and textile sector of Pakistan. Such companies were selected for data collection whose operations leave a footprint on the environment and where green practices have been introduced in some form through official channels. The information was obtained through company brochures, websites, social networks, and news media. Such practices included utilizing renewable energy for some or all of the energy demands through solar panels on the rooftop, or offsetting the organization’s carbon emissions, initiatives of recycling excess and waste materials, recycling metal furniture and objects for other purposes, and using recycled yarn and threads from plastic objects cleaned up from the coastal areas.

This study employed convenience sampling for selecting 124 companies listed on Karachi Stock Exchange, and Islamabad Stock Exchange was contacted to obtain consent for participation between June 2021 and July 2021. Communication was made with the HR department of the shortlisted organizations through emails and telephone calls briefing about the academic purpose of the research and voluntary and anonymous participation of the respondents. By the end of July 2021, 104 companies replied to our request, and 76 indicated agreement to participate. However, 42 companies participated after approval from relevant authorities. The authors shared inclusion criteria with the HR department of the respective companies that agreed to allow their employees’ participation in the research. Inclusion criteria delineate that the respondents should have at least two years of experience within the company with a minimum of one year of experience under their current supervisor, showing that respondents were familiar with the company operations and employee-supervisor dyads were familiar with each other for a reasonable time for behavioral influences. The HR department was further requested to randomly select every 3rd team in the organization and share the names and email addresses of the team leader (supervisor) and members (employees). The exercise resulted in a master list of 116 teams with 462 employees from 42 companies. The number of employees (team members) ranged from 4 to 7 in each team.

Two distinctive forms, separate for employees and supervisors, were designed with the help of Google Docs for online data collection from the respondents. The nature of the study may make the respondents prone to social desirability bias (Davis et al., 2010), which was tackled through a cover letter assuring that the respondents’ participation shall be kept confidential and voluntary, and purely for academic purposes. The questionnaires were administered in English, Pakistan’s official and widely understood communication language. The respondents, the team leader (supervisor), and members (employees) were invited through an invitation email containing a link to online designed forms for participation in the survey. Questionnaires were executed in two phases; during the first phase (T1), held in August 2021, the questionnaire was administered to employees who rated their supervisor’s responsible leadership behavior, leader identification, and autonomous motivation for the environment. In the second phase (T2), carried out in September 2021, supervisors were asked to report the VGB of employees within their supervision. This procedure addressed resolving potential single-rater bias issues (Podsakoff et al., 2003) and minimized the potential impact of the social desirability bias. Further, following the recent publication (Islam et al., 2020), the questionnaire of employees contained shuffled questions of different constructs as a remedial measure for reducing common method bias. During each data collection phase, two reminders one week apart were emailed to non-respondents.

The final matched responses of 357 employees in 97 teams from 36 firms were obtained at both time points (supervisor responses for the second phase were not received from 6 companies out of the initial 42), with a response rate of 83.62% for managers and 77.27% for employees. A 73.11% of the respondents were male, 57.98% were aged 35 and above, 55.74% had a Master’s degree, 33.33% held a Bachelor’s degree, 48.74% had at least five years tenure, and 51.26% had less than five years tenure. Early and late responders (first and last 25%) were compared, and no discernible differences were observed. A minimum sample size of 55 was determined with G-Power 3.1.9 software with a minimum effect size of .15, .80 power, and .05 Alpha for three predictors. This study’s sample size reasonably exceeds the minimum required size.

Measures

All constructs were evaluated through established and validated measures on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘1’ strongly disagree to ‘7’ strongly agree. Employees’ VGB was gauged by the rating from their supervisors’ on a ten-item scale developed by Robertson and Barling (2017). On the other hand, employees assessed their immediate supervisors’ responsible leadership on a five-item scale developed by Voegtlin (2011). Employees’ responded to their level of autonomous motivation for the environment through the twelve-item measure for motivation towards the environment developed by Pelletier et al. (1998). Lastly, leader identification was tapped through employees’ responses on a five-item adapted measure of Mael and Ashforth (1992). Appendix Table 8 presents all items of constructs under consideration in this research.

Following similar studies (Abbas et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2022), respondents’ gender, age, tenure, and group size were taken as control variables. The reason for evaluating these controls was that some prior research indicates age, gender, and education have a weak association with green behavior(Ying et al., 2020), and another showed a weak relationship with tenure and group size (Kim et al., 2017). However, all these proved non-significant in this study and were removed from the structural model.

Results and analysis

Hypothesis testing methods

The variables in this study involved both team and individual levels, so multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM) was used to test the research hypotheses of this study (Preacher et al., 2010). SPSS 21.0 software was used for calculating the variables’ means and standard deviations, and Mplus 8.3 was used for robust maximum likelihood estimation to test hypotheses.

Data aggregation

Using the Mplus 8.3 software application, responsible leadership and leader identification were checked for possible aggregation at the firm and team levels. The firm-level aggregation was statistically not significant. However, team-level aggregation results were statistically significant. Intra-class correlation values for ICC (1) (RL = .21, LI = .17) and mean group score ICC(2) (RL = .72, LI = .74) were above the suggested benchmark values of .12 and .47, respectively. Moreover, the group-level agreement was checked through mean score values of within-group consistency (Rwg) (RL = .79 and LI = .73), also above the recommended cutoff value of .70 (Fleiss, 1999). significant between-group variance and Rwg values were large enough, establishing that the two variables could be aggregated from individual to team levels. Therefore, a multilevel analysis was carried out.

First, the reliability of the measures was established through composite reliability (CR) because it generates precise estimates of reliability based on factor loadings (Geldhof et al., 2014). The values were above the recommended .80 benchmarks for all the constructs (see Table 1). Second, Mplus 8.3 was used for confirmatory factor analysis, and factor loadings were above the recommended threshold of .600 (p < .001), which indicates high reliability. Third, convergent and discriminant validity were established based on recommendations by Fornell and Larcker (1981). The average variance extracted (AVE) was checked and was found to be higher than the threshold value of .500 (items forming the construct accounted for at least 50% of its variance, indicating convergent validity. The square root values of the AVE were used to compare correlations and ascertain discriminant validity. Multicollinearity was assessed through variance inflation factor (VIF) at the factor level with a benchmark value of 3 (Lin, 2008); all values were below the recommended threshold of 3 for all relevant constructs (RL ->VGB = 1.64, RL -> LI = 1.58, RL -> AME = 2.14, LI->VGB = 1.98, AME->VGB = 1.86).

Model fit

Mplus 8.3 was used to compare the fit indices of alternate models with the baseline four-factor model (see Table 2). The baseline model fit the data well [Chi Square/df ratio (χ2/df) = 2.45, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .037, comparative fit index (CFI) = .94, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = .95, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .04, p < .001] and significantly better than three-factor, two-factor, and single-factor models. This indicated satisfactory discriminant validity among this study’s variables and that the common method bias was not a serious concern.

Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, coefficients) are displayed in Table 3, correlating data at two levels. First, the correlation was not high, and the main study variables showed a positive correlation, signifying that underlying hypotheses were tentatively verified.

Hypothesis testing

Multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM) was used to perform multilevel confirmatory factor analysis, as Geldhof et al. (2014) recommended. The results indicated goodness of fit. Next, a structural model was constructed to confirm that responsible leadership positively affects employee voluntary green behavior through LI and AME. Nested models were tested and compared; the results are shown in Table 4. The fit indexes of the baseline model [χ2/df = 2.05, RMSEA = .036, CFI = .94, TLI = .93, SRMR within/between group = .042/.058] were better when compared with alternative models, indicating it as the optimal path model for hypothesis testing (Vexler et al., 2010).

The structural model’s normalized coefficients for each path are shown in Table 5 as the baseline model. The analysis supports hypothesis 1 with a significant positive relationship between responsible leadership and VGB (β = .398, p < .001). Hypothesis 2 and 3 were also confirmed for mediating effects of leader identification and autonomous motivation for the environment with verified “2-2-1” and “2-1-1” models recommended by Preacher et al. (2010). Table 6 shows that the estimates were statistically significant, and 95% confidence intervals did not include a zero value for both mediation paths. The results of the structural model are presented in Figure 2.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the effect of responsible leadership on employees’ VGB through the mediating mechanism of autonomous motivation for the environment and leader identification. The results showed that responsible leadership, autonomous motivation for the environment, and leader identification explained 52% of the variance in employees’ VGB. The direct effect of responsible leadership on employees’ VGB is significant. Besides, the Mediation results demonstrated that autonomous motivation for the environment and leader identification mediates the relationship between responsible leadership and employees’ VGB. However, the mediation through autonomous motivation for the environment yielded higher values of β and t-statistics than leader identification. Overall the results are consistent with theoretical underpinnings and empirical evidence.

Theoretical implications

Although some studies have investigated the impact of responsible leadership on OCBE or socially responsible behaviors, this is the pioneering research investigating the influence of responsible leadership on employees’ VGB. Secondly, this study advances debate and discourse on applying self-determination and social identity theories to investigate the influencing mechanism of responsible leadership toward employees’ VGB. The theories of social identity and self-determination differ in each one of their locus of control (external and internal, respectively). The combined theoretical underpinning refers to applying the leader-specific (responsible leader and leader-identification) and individual-specific (self-reported) perspectives within one framework instead of discussing them in separate models with a singular theoretical perspective from either external or internal locus of control-related variables, leader-subordinate interaction or impact-related variables; instead, we discuss them under the umbrella of two theories because in real life phenomenon theories do not operate mutually exclusively. Lastly, this study contributes to the existing body of knowledge on responsible leadership from a socio-psychological perspective and identifies a mechanism that environmentally responsible leaders use to promote green behaviors among their employees. Finally, the mediation results give more profound insights into where autonomous motivation for the environment is more closely associated with responsible leadership and employees’ VGB relationship than leader identification. Results also align with a recent study on CEOs’ environmentally responsible leadership toward environmental innovation (Li et al., 2020).

This study gives credence to the notion that autonomous motivation for the environment strongly nurtures individual behaviors, and an individual makes choices primarily based on internalized conceptions and ideas about the environment (Kaplan & Madjar, 2015). An employee needs to feel engaged in VGB because such engagement in environmental protection brings satisfaction and self-fulfillment from contributing to society. Thus, such behaviors are encouraged, rewarded, or supported intrinsically, at the least, if not extrinsically. A more recent study found that the autonomous motivation of employees mediates the relationship between responsible leadership and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment ((Han et al., 2019a). This result of the mediation of AME between responsible leadership and green behaviors is similar to a previous study by Graves et al. (2013) that indicated autonomous motivations and external motivations as antecedents of employees’ environmentally responsible lifestyles. Along these lines, employees’ VGB prompted by autonomous motivation, inherently agrees with employees’ interests, values, and goals at the individual level (Gagné & Deci, 2005). This is why even in the absence of extrinsic rewards, an employee still chooses to engage in VGB. The same logic has been indicated by the findings of a study (Osbaldiston & Sheldon, 2003)that examined students’ pro-environmental behaviors of recycling, energy-saving, and using environment-friendly products. The results indicate that the autonomous motivation of students to protect the environment has a positive relationship with actual pro-environmental behavior.

Additionally, this study indicates that responsible leadership behaviors tend to permeate the hierarchy throughout the firm with leader identification while encouraging employees to undertake green behaviors at the workplace. These results resonate with findings of studies on positive leadership style and employee behaviors (Maier & Branzei, 2014; Wang et al., 2020), which observed that employees follow the example of their leader to perform VGB as their contribution to the environmental initiatives, e.g., resources conservation, reduced energy consumption, generating ideas on how to minimize waste and recycle. The results also align with previous findings by Chen and Chang (2013) on middle managers’ initiatives inspired by the CEO’s responsible behavior toward green product development. Therefore, this study’s findings provide insights into potential driving forces of leader identification and autonomous motivation with environmental issues for employees and managers alike to inculcate more engagement with voluntary green behaviors. Responsible leadership emphasizes constructive and sustainable relationship-building among internal and external stakeholders (Maak & Pless, 2006). This study is different in that it uses an internalized focus on internal stakeholders’ behavior instead of most of the past decade’s research focusing on the external stakeholder perspective and how it pressurizes an organization from outside to appear socially responsible and engage in pro-environmental behaviors. This study adds to the recently growing literature on identifying mechanisms through which responsible leadership is mobilizing internal stakeholders towards green behavior and environmental protection, i.e., top management engaging mid-level management in environmentally responsible behavior and spreading the effect to the individual employee level.

Another contribution of this study is that it introduces social identity theory to green behaviors as part of socially responsible behaviors. Notably, it examines the collective impact of how an internalized process of autonomous motivation and leader identification among employees is inspired by responsible leadership, which further translates into voluntary green behaviors. Responsible leadership stimulates employees who identify their personal beliefs with their leader, inspiring them to engage in green behaviors voluntarily. The extant literature has seen extensive use of social identity theory to explain the processes leaders use to cultivate various organizational behaviors among employees through developing self-concept within an organization (van Knippenberg et al., 2005). However, most of the research has focused on an individual-level identification process while overlooking what or whom the individual employee is identifying with. This study moves beyond a generalized association of social identity with follower behavior at an organizational level (Zhang & Chen, 2013) and further examines why and how responsible leaders concerned with environmental issues can become instrumental in enhancing voluntary green behaviors which move beyond the restriction of the organizational boundaries into the social interactions as well.

Practical implications

A company’s corporate outlook and reputation are among the primary outcomes for which firms take up environmentally friendly initiatives. This is also seen in business media, where rankings and proclamations are carried out for more green and not-so-green companies for their environmental performance, such as Green Rankings Global 500. This notion also extends to the financial institutions for green investments, with new green indices such as FTSE4Good as moral guidance for investment decisions. Consumers are signaling their desire for more environmentally friendly products. Understanding individual predispositions associated with VGB may provide helpful guidance for recruiting, identifying, and selecting employees likely to perform well in such positions. Our research suggests that conscientiousness and moral reflectiveness (along with other predictors) may contribute to the successful performance of new, greener jobs because both individual factors are considered human capital for green volunteers. For organizations that address environmental concerns by relying exclusively on voluntary behavioral changes, recruiting and selecting new hires, and promoting leaders for all jobs using information about conscientiousness and moral reflective behavior may be a way to improve the organization’s environmental performance. However, we offer these ideas cautiously as more direct interventions are needed to improve environmental performance significantly. Finally, when such significant interventions are implemented, our results suggest that having a solid cadre of conscientious and morally reflective leaders and non-leaders is likely to improve the efficacy of such interventions.

Top and middle management need a company-wide impetus to trickle down the effects of environmentally responsible and green initiatives amongst employees. Leadership has the most decisive influence because their environmentally responsible style indicates a company’s seriousness in its initiatives. A recent study on CEOs’ environmentally responsible leadership toward environmental innovation (Li et al., 2020) found that when top management displays responsible behavior towards their environment, they tend to ensure the allocation of sufficient resources and support to align operations with the pro-environmental vision. In developing economies, organizations can enhance employees’ VGB through responsible leadership because it resonates with employees’ independent motivation for the environment through their leader identification. Thus, there is a dire need to emphasize the role of responsible leadership in the sustainable development of organizations. While inspiring the autonomous motivation for the environment of employees to engage in environmental activities, responsible leaders can shift the continuum from identified motivation to intrinsic motivation. This effect culminates from an individual action into a collective team level and forms organizational initiatives towards environmentally responsible behaviors. Employees, as individuals, reflect upon their status quo when they see their leaders behave responsibly towards the environment, and this culminates into voluntary behavior change, which Hofmann et al. (2009) refer to as reflective precursors of behavior change.

Managers are expected to affect behavioral change while implementing policies and procedures at the organizational and team levels. As Maak and Pless (2006) argue, the critical role of a responsible leader is to be a facilitator, mainly because the primary addressee of any leadership is an employee. Therefore, it is vital to maintain the sanctity of the leader-follower relationship, which is an essential part of responsible leadership behaviors. The process of implementing an organization’s environmental policy and initiatives is dependent on leaders who facilitate behaviors at the workplace. Employees’ AME is boosted when they see their leaders are also motivated towards environmental initiatives.

Leader identification can be an effective method for promoting VGB. Organizations should incentivize leaders to pay attention to those attributes that enhance their identification with employees. For example, a leader may offer individual-level support while considering employee needs, be open to subordinates for new ideas, and encourage their personal growth. This leads to a trusting, supportive work environment where employees feel valued and engaged in VGB because they identify with the responsible leader’s behavior.

Organizations should make it a matter of policy to train leaders on how they can communicate and make visible their responsible behaviors to their subordinates. Employees feel strongly inclined to generate a constructive social exchange relationship with their leader, whom they identify as responsible. They care more and display an understanding of the leader’s demands, and are keen on selflessly satisfying his expectations.

Research limitations and future directions

Like other research in social sciences, our study also contains a few limitations. First, causal inferences cannot be made based on our study because it was cross-sectional. Further, this research investigated the role of only two mediators where future research should include additional mediators and moderators to enrich the understanding of the responsible leadership and employees’ VGB relationship. This research was conducted in a male-dominated society where gender differences have not been explored extensively. The sample also included a minority of females. The results may be generalized to other countries with caution, and future research may explore this aspect in detail for its antecedents or outcomes depending upon gender mix or differences.

This study did not account for the corporate environmental policy of the firms as an antecedent, which is also a possible variable of interest in determining environmentally responsible leadership behaviors. Another possible avenue for future research is to study the multilevel trickle-down effect of responsible leadership from CEOs onto managers and operations-level employees. The Corporate environmental strategy of a firm and how it shapes employee behaviors should also be studied. Moreover, this study’s context and geographical location also posit another limiting aspect. The population in Pakistan consists of more than 95% Muslims. The role of religious beliefs in developing morals that are closely related to or appear in the form of responsible behaviors towards the environment may need to be further explored. Thus, assessing religious and cultural beliefs as a moderating variable of responsible leadership could interest researchers in future studies. Similarly, further factors may be studied in different cultural and religious settings (e.g., China, where most of the population follows Atheism but is still characterized by collectivism, high power distance, and uncertainty avoidance, as in Pakistan). This study in Pakistan differed from prior studies in developed countries’ contexts and some developing countries’ contexts because of the existence of visible enforcement of environmental laws. Another limitation of our study is that a comparison between Pakistan and other contexts could not be made to observe possible differences in the strength of hypothesized relationships with another developed or developing country with stringent environmental laws and government enforcement. Future studies could conduct a comparative study with data from two countries for comparison.

Data availability

Authors do not have permission to share data due to restrictions by the university.

References

Abbas, A., Chengang, Y., Zhuo, S., Manzoor, S., Ullah, I., & Mughal, Y. H. (2021). Role of responsible leadership for organizational citizenship behavior for the environment in light of psychological ownership and employee environmental commitment: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(1), 01–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.756570

Abubakar, S. (2020). Pakistan 5th most vulnerable country to climate change, reveals Germanwatch report. DAWN. Retrieved April 23, 2022 from https://www.dawn.com/news/1520402

Afsar, B., Maqsoom, A., Shahjehan, A., Afridi, S. A., Nawaz, A., & Fazliani, H. (2020). Responsible leadership and employee’s proenvironmental behavior: The role of organizational commitment, green shared vision, and internal environmental locus of control. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(1), 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1806

Andersson, L., Jackson, S. E., & Russell, S. V. (2013). Greening organizational behavior: An introduction to the special issue. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2), 151–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1854

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4278999

Chen, Y. S., & Chang, C. H. (2013). The determinants of green product development performance: Green dynamic capabilities, green transformational leadership, and green creativity. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(1), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1452-x

Daily, B. F., Bishop, J. W., & Govindarajulu, N. (2009). A conceptual model for organizational citizenship behavior directed toward the environment. Business & Society, 48(2), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650308315439

Davis, C. G., Thake, J., & Vilhena, N. (2010). Social desirability biases in self-reported alcohol consumption and harms. Addictive Behaviors, 35(4), 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.001

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Faraz, N. A., Ahmed, F., Ying, M., & Mehmood, S. A. (2021). The interplay of green servant leadership, self-efficacy, and intrinsic motivation in predicting employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(4), 1171–1184. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2115

Fleiss, J. (1999). Reliability of Measurement. In The design and analysis of clinical experiments (pp. 1–32). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118032923.ch1

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

Gagné, M., & Deci, E. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322

Geldhof, G. J., Preacher, K. J., & Zyphur, M. J. (2014). Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychological Methods, 19(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032138

Graves, L. M., Sarkis, J., & Zhu, Q. (2013). How transformational leadership and employee motivation combine to predict employee proenvironmental behaviors in China. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 35, 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.05.002

Groves, K. S. (2011). Integrating leadership development and succession planning best practices. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 39(3), 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMR.2011.6019093

Gumusluoglu, L., Karakitapoğlu-Aygün, Z., & Scandura, T. A. (2017). A multilevel examination of benevolent leadership and innovative behavior in r&d contexts: A social identity approach. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 24(4), 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051817705810

Guo, Y. G., Zhu, Y. T., & Zhang, L. H. (2020). Inclusive leadership, leader identification and employee voice behavior: The moderating role of power distance. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00647-x

Han, Z., Wang, Q., & Yan, X. (2019a). How responsible leadership motivates employees to engage in organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: A double-mediation model. Sustainability, 11(3), 605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030605

Han, Z., Wang, Q., & Yan, X. (2019b). How responsible leadership predicts organizational citizenship behavior for the environment in China. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1108/lodj-07-2018-0256

He, J., Morrison, A. M., & Zhang, H. (2021). Being sustainable: The three-way interactive effects of CSR, green human resource management, and responsible leadership on employee green behavior and task performance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(3), 1043–1054. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2104

Hofmann, W., Friese, M., & Strack, F. (2009). Impulse and self-control from a dual-systems perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(2), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01116.x

Islam, T., Khan, M. M., Ahmed, I., & Mahmood, K. (2020). Promoting in-role and extra-role green behavior through ethical leadership: Mediating role of green HRM and moderating role of individual green values. International Journal of Manpower, 42(6), 1102–1123. https://doi.org/10.1108/Ijm-01-2020-0036

Ismail, S. S. M., & Hilal, O. A. (2022). Behaving green who takes the lead? The role of responsible leadership, psychological ownership, and green moral identity in motivating employees green behaviors. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, early access. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22177

Kanwal, S. (2018). The environmental issues in Pakistan. The Frontier Post. Retrieved March 22 from https://thefrontierpost.com/the-environmental-issues-in-pakistan/

Kaplan, H., & Madjar, N. (2015). Autonomous motivation and pro-environmental behaviours among bedouin students in Israel: A self-determination theory perspective. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 31(2), 223–247. https://doi.org/10.1017/aee.2015.33

Kim, K. S., Sin, S. C. J., & Tsai, T. I. (2014). Individual differences in social media use for information seeking. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40, 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.03.001

Kim, A., Kim, Y., Han, K., Jackson, S. E., & Ployhart, R. E. (2017). Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. Journal of Management, 43(5), 1335–1358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314547386

Li, Z., Xue, J., Li, R., Chen, H., & Wang, T. (2020). Environmentally specific transformational leadership and employee’s pro-environmental behavior: The mediating roles of environmental passion and autonomous motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(1408). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01408

Liao, Z., & Zhang, M. (2020). The influence of responsible leadership on environmental innovation and environmental performance: The moderating role of managerial discretion. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(5), 2016–2027. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1942

Liao, Y., Liu, X. Y., Kwan, H. K., & Li, J. (2015). Work–family effects of ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 535–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2119-6

Lin, F. J. (2008). Solving multicollinearity in the process of fitting regression model using the nested estimate procedure. Quality & Quantity, 42(3), 417–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-006-9055-1

Lu, H., Xu, W., Cai, S., Yang, F., & Chen, Q. (2022). Does top management team responsible leadership help employees go green? The role of green human resource management and environmental felt-responsibility. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(4), 843–859. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2239

Maak, T., & Pless, N. M. (2006). Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society – a relational perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 66(1), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9047-z

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 103–123. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130202

Maier, E. R., & Branzei, O. (2014). On time and on budget”: Harnessing creativity in large scale projects. International Journal of Project Management, 32(7), 1123–1133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.02.009

Miska, C., & Mendenhall, M. E. (2018). Responsible leadership: A mapping of extant research and future directions. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2999-0

Norton, T. A., Parker, S. L., Zacher, H., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2015). Employee green behavior:A theoretical framework, multilevel review, and future research agenda. Organization & Environment, 28(1), 103–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026615575773

Norton, T. A., Zacher, H., Parker, S. L., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2017). Bridging the gap between green behavioral intentions and employee green behavior: The role of green psychological climate. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(7), 996–1015.

Osbaldiston, R., & Sheldon, K. M. (2003). Promoting internalized motivation for environmentally responsible behavior: A prospective study of environmental goals. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23(4), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(03)00035-5

Pelletier, L. G., Tuson, K. M., Green-Demers, I., Noels, K., & Beaton, A. M. (1998). Why are you doing things for the environment? The motivation toward the environment scale (MTES). Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(5), 437–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01714.x

Pless, N. M. (2007). Understanding responsible leadership: Role identity and motivational drivers. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(4), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9518-x

Pless, N. M., & Maak, T. (2011). Responsible leadership: Pathways to the future. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1114-4

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020141

Priyankara, H. P. R., Luo, F., Saeed, A., Nubuor, S. A., & Jayasuriya, M. P. F. (2018). How does leader’s support for environment promote organizational citizenship behaviour for environment? a multi-theory perspective. Sustainability, 10(1), 271. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/1/271. Accessed 15 Mar 2023

Robertson, J. L., & Barling, J. (2017). Toward a new measure of organizational environmental citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Research, 75, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.02.007

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68

Singh, S. K., Del Giudice, M., Chierici, R., & Graziano, D. (2020). Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 150(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119762

Stahl, G. K., & Luque, M. S. (2014). Antecedents of responsible leader behavior: A research synthesis, conceptual framework, and agenda for future research. Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(3), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2013.0126

Tian, H., & Suo, D. (2021). The trickle-down effect of responsible leadership on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors: Evidence from the hotel industry in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111677

Tuan, L. T. (2019). Effects of environmentally-specific servant leadership on green performance via green climate and green crafting. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 38(3), 925–953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-019-09687-9

Ullah, I., Wisetsri, W., Wu, H., Shah, S. M. A., Abbas, A., & Manzoor, S. (2021). Leadership styles and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The mediating role of self-efficacy and psychological ownership. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 683101. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.683101

van Knippenberg, D., van Knippenberg, B., De Cremer, D., & Hogg, M. (2004). Leadership, self, and identity: A review and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(6), 825–856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.002

van Knippenberg, B., van Knippenberg, D., De Cremer, D., & Hogg, M. A. (2005). Research in leadership, self, and identity: A sample of the present and a glimpse of the future. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(4), 495–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.06.006

Vexler, A., Wu, C., & Yu, K. F. (2010). Optimal hypothesis testing: From semi to fully bayes factors. Metrika, 71(2), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00184-008-0205-4

Voegtlin, C. (2011). Development of a scale measuring discursive responsible leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(1), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1020-9

Voegtlin, C., Frisch, C., Walther, A., & Schwab, P. (2019). Theoretical development and empirical examination of a three-roles model of responsible leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 167(1), 411–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04155-2

Walumbwa, F. O., & Hartnell, C. A. (2011). Understanding transformational leadership–employee performance links: The role of relational identification and self-efficacy. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317910X485818

Wang, X., Zhou, K., & Liu, W. (2018). Value congruence: a study of green transformational leadership and employee green behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(1946). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01946

Wang, Y., Font, X., & Liu, J. (2020). Antecedents, mediation effects and outcomes of hotel eco-innovation practice. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 85, 102345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102345

Wang, Y., Shen, T., Chen, Y., & Carmeli, A. (2021). CEO environmentally responsible leadership and firm environmental innovation: A socio-psychological perspective. Journal of Business Research, 126, 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.01.004

Xiao, X., Zhou, Z., Yang, F., & Qi, H. (2021). Embracing responsible leadership and enhancing organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: A social identity perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 632629. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.632629

Ye, J., Zhang, X., Zhou, L., Wang, D., & Tian, F. (2022). Psychological mechanism linking green human resource management to green behavior. International Journal of Manpower, (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-11-2020-0508

Ying, M., Faraz, N. A., Ahmed, F., & Raza, A. (2020). How does servant leadership foster employees’ voluntary green behavior? a sequential mediation model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), Article 1792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051792

Yuriev, A., Boiral, O., Francoeur, V., & Paillé, P. (2018). Overcoming the barriers to pro-environmental behaviors in the workplace: A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.041

Zhang, Y., & Chen, C. C. (2013). Developmental leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: Mediating effects of self-determination, supervisor identification, and organizational identification. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(4), 534–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.03.007

Zhang, Y., Zheng, Y., Zhang, L., Xu, S., Liu, X., & Chen, W. (2019). A meta-analytic review of the consequences of servant leadership: The moderating roles of cultural factors. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 38(1), 371–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9639-z

Zhang, J., Ul-Durar, S., Akhtar, M. N., Zhang, Y., & Lu, L. (2021). How does responsible leadership affect employees’ voluntary workplace green behaviors? A multilevel dual process model of voluntary workplace green behaviors. Journal of Environmental Management, 296, 113205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113205

Zhao, H., & Zhou, Q. (2019). Exploring the impact of responsible leadership on organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: A leadership identity perspective. Sustainability, 11(4), 944, Article 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11040944

Zhu, W., He, H., Trevino, L. K., Chao, M. M., & Wang, W. (2015). Ethical leadership and follower voice and performance: The role of follower identifications and entity morality beliefs. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(5), 702–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.01.004

Funding

This study is supported by the Key Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China (21AJY016) and the major Project of the Social Science Achievement Appraisal Committee of Hunan Province (XSP21ZDA010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics and informed consent

The researchers clarified the academic nature of the study and obtained approval from relevant authorities in organizations to proceed with data collection. The questionnaire included a clear statement assuring participants of complete anonymity, confidentiality, explained they had the right to withdraw anytime during the study, and that proceeding to fill in the questionnaire shall deem their informed consent. The study was non-invasive, did not involve any intervention or manipulation of the human subjects, and participants were not vulnerable to any physical or psychological harm. Responses were accessible by researchers only.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, F., Faraz, N.A., Xiong, Z. et al. The multilevel interplay of responsible leadership with leader identification and autonomous motivation to cultivate voluntary green behavior. Asia Pac J Manag (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09893-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09893-6