Abstract

The paper advances the conceptual understanding of responsible leadership and develops an empirical scale of discursive responsible leadership. The concept of responsible leadership presented here draws on deliberative practices and discursive conflict resolution, combining the macro-view of the business firm as a political actor with the micro-view of leadership. Ideal responsible leadership conduct thereby goes beyond the dyadic leader–follower interaction to include all stakeholders. The paper offers a definition and operationalization of responsible leadership. The studies that have been conducted to develop the discursive responsible leadership scale validated the scale, discriminated it from other leadership scales, and demonstrated its utility in affecting unethical behavior and job satisfaction in organizations. Responsible leadership is shown to be first, dependent on the hierarchical level in an organization; second, capable of reducing unethical treatment of employees; and finally, a means of enhancing the job satisfaction of employees. The paper concludes with study limitations, future research directions and practical implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The need for a new understanding of leadership that can address the future challenges of globalization (Maak 2007; Maak and Pless 2006b; Scherer and Palazzo 2007, 2008a) and transcend the instrumental view of leadership in neo-institutional theory (Waldman and Galvin 2008) has inspired a great deal of research under the umbrella term of responsible leadership (see e.g., Doh and Stumpf 2005a; Maak and Pless 2006a; Pless 2007; Waldman and Galvin 2008; Waldman and Siegel 2008). The field of responsible leadership has made promising progress in closing the gap between the extended research on corporate social responsibility (CSR) on the organizational level and the growing urge to address the responsibility of business leaders (Maak 2007; Maak and Pless 2006b; Pless 2007).

Yet, there is still a need for future scholarly attention. In the field of responsible leadership, I distinguish three areas of interest that call for a changing understanding of leadership and an extended responsibility of leaders in organizations. These areas have not been addressed sufficiently in academic literature and warrant future research. First, from a normative point of view, authors convincingly call for an extended (political) responsibility of organizations due to the globalization process and the new challenges for business firms that go along with it (Matten and Crane 2005; Palazzo and Scherer 2006; Scherer and Palazzo 2007, 2008b). This, in turn, implies a call for greater responsibility on the part of the central actors in organizations—the leaders—especially in relation to CSR or an extended stakeholder management (Bies et al. 2007; Doh and Stumpf 2005b; Palazzo and Scherer 2008; Waldman and Siegel 2008, p. 117; Waldman et al. 2006). Second, from an instrumental point of view, organizations face growing demands from external constituencies (stakeholders). Those constituencies, if neglected, can withdraw the organizations’ “license to operate,” and thus threaten their survival, and/or add to the creation of organizational wealth (e.g., through engagement in mutual beneficial relationships influenced by organizational leaders) (Agle et al. 2008; Freeman 1984; Laplume et al. 2008; Post et al. 2002). Leaders should be able to guarantee their organization’s license to operate. This, however, implies an understanding of leadership that goes beyond the dyadic leader–follower model and extends to a broader engagement between leaders and stakeholders (Maak 2007; Maak and Pless 2006b; Voegtlin et al. 2011). Finally, the descriptive reality shows that business leaders in recent crises or scandals have not always lived up to their responsibility. This deviance in the leaders’ sense of responsibility had severe effects on their firms’ license to operate and subsequently on organizational performance. In some cases even the whole existence of firms was put at risk. Yet, apart from a few exceptions (see e.g., De Hoogh and Den Hartog 2008; Pless 2007), insufficient descriptive and predictive empirical research on responsible leadership has been conducted. This could be due to the lack of an appropriate instrument.

Therefore, this article extends an understanding of responsible leadership that first, from a normative perspective should enable leaders to act ethically by guiding them in establishing generally accepted norms and values through dialogue with all affected constituencies; second, from an instrumental perspective can grant the organization a license to operate; and third, offers an empirical scale of discursive responsible leadership that offers descriptive and predictive access to the phenomenon of responsible leadership. I thereby draw on the conception of responsible leadership as forwarded by Maak and Pless (Maak 2007; Maak and Pless 2006b; Pless 2007), and Patzer and colleagues (Patzer 2009; Patzer and Scherer 2010; Voegtlin et al. 2011).

The main focus of the paper is the development of an empirical scale of discursive responsible leadership. By operationalizing responsible leadership, the paper advances theory and research. It lays the conceptual and empirical groundwork to extend the (empirical) knowledge on responsible leadership. This groundwork comprises a definition of responsible leadership as discursive conflict resolution and deliberative practices, and is advanced by the discursive responsible leadership scale. The instrument is tested for its psychometric properties and its utility in predicting outcomes.

The Responsible Leadership Concept

Globalization has changed the conditions for business organizations and leadership (Scherer and Palazzo 2008a; Scherer et al. 2009). The liberalization of markets coinciding with new technological developments, a culturally heterogeneous and mobile workforce, and a growing critical (world) society organized in the form of global NGOs, are just a few examples of the challenges of globalization. These challenges have been accompanied by a decline of the regulatory power of the nation-state (Beck 2000; Habermas 2001b). Evolving gaps in governance on the global level due to the liberalization of markets have restricted nation-states’ power to regulate those markets and to guarantee stable conditions for economic actors (Habermas 2001b; Scherer and Palazzo 2007; Scherer et al. 2006). These developments have prompted theorizing about the extension of corporate responsibility (see e.g., Crane et al. 2008; Scherer and Palazzo 2008b). Authors call for a role of firms as corporate citizens or as political actors (Matten and Crane 2005; Scherer and Palazzo 2007) that engage in a proactive stakeholder management to secure both their legitimacy and their license to operate in a global society (Palazzo and Scherer 2006).

This relates to and directly affects the actions of organizational leaders. While leaders have to secure the legitimacy of their organization, they are under growing pressure to optimize its performance. Business leaders are confronted with the demands of many different and culturally heterogeneous stakeholder groups from inside and outside the organization. They face ever more complex decision situations (including difficult moral dilemmas), to which they must find solutions that are acceptable to all affected parties. As Maak (2007, p. 330) states: “in an interconnected and multicultural global stakeholder society, moral dilemmas are almost inevitable. How can one adhere to fundamental moral principles while still respecting cultural differences and taking into consideration different developmental standards?”

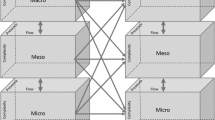

A global stakeholder society with such a great variety of demands calls for an understanding of leadership that first, transcends the dyadic leader–follower model to an understanding of leadership as leader–stakeholder interaction (Maak and Pless 2006b); second, can provide normative orientation for dealing with heterogeneous cultural backgrounds or complex moral dilemmas; and third, enables leaders to produce (moral or ethical) decisions, thereby bringing different interests to satisfying and, if possible, mutually beneficial solutions. Scholars have recognized the need for such an understanding of leadership (Doh and Stumpf 2005a; Maak and Pless 2006a; Waldman and Galvin 2008; Waldman and Siegel 2008). Maak and Pless (Maak 2007; Maak and Pless 2006b; Pless 2007) deduce a concept of responsible leadership as a “value-based and through ethical principles driven relationship between leaders and stakeholders” (Pless 2007, p. 438). They have formulated a roles model of responsible leadership in which “the responsible leader acts as a weaver of stakeholder relationships” (Maak 2007, p. 340), thereby leveraging social capital for the organization. Patzer and colleagues (Patzer 2009; Patzer and Scherer 2010; Voegtlin et al. 2011) connect to this understanding and extend it in that they place this concept against the theoretical background of discourse ethics and deliberative politics. This conceptualization of responsible leadership is connected to the discussion of the firm as a political actor (Palazzo and Scherer 2006; Scherer and Palazzo 2007; Scherer et al. 2006, 2009), drawing on Habermas’s ideas on discursive conflict resolution and deliberative practices (e.g., Habermas 1993, 1998, 2001a).

Responsible leadership is thereby a procedural conception, based on an ideal of political autonomy and practical reasoning by citizens. It becomes manifest in the inclusion and mobilization of stakeholders in a communicative process, where conflicting interests are evaluated according to their legitimate arguments and settled through rational discourse (Patzer 2009; Voegtlin et al. 2011). Responsible leadership can thus be understood as the awareness and consideration of the consequences of one’s actions for all stakeholders, as well as the exertion of influence by enabling the involvement of the affected stakeholders and by engaging in an active stakeholder dialogue. Therein responsible leaders strive to weigh and balance the interests of the forwarded claims.

The definition is based on the steps of discursive conflict resolution. The conditions for an ideal discourse require that all affected persons have equal chances to participate in the discourse, allowing them to advocate their position and critique other positions in a condition of symmetrical power relations (Habermas 1993; Stansbury 2009, p. 41). Responsible leadership in this context means that leaders have to recognize (moral) problems by considering the consequences of their decisions or actions for all possibly affected constituencies. They should then use their influence to incorporate stakeholder-groups into the decision-making process by providing arenas for discussion and dialogue. The arguments are evaluated from the perspectives of all affected stakeholders. The responsible leader thereby advocates arguments that emphasize the point of view of the organization. Further, he or she tries to achieve a consensus among the participants by weighing and balancing the different interests.

This understanding of responsible leadership is conceptualized as an ideal based on high moral standards. Such an ideal encounters restrictions in the day-to-day business of an organization (see e.g., Stansbury 2009). We therefore assume that the conceptualization of responsible leadership represents a continuum, ranging through non-responsible leadership, which can be characterized as self-interested, egoistic leadership behavior acting solely on an instrumental rationale, to the responsible leader acting according to the ideal presented above.

Responsible Leadership in Relation to Transformational and Ethical Leadership

In this section I highlight the main similarities and differences of responsible leadership in relation to the leadership concepts of ethical leadership (Brown and Trevino 2006; Brown et al. 2005) and transformational leadership (Bass 1985; Bass and Avolio 1994; Podsakoff et al. 1990). Both concepts will be used to draw the empirical distinction among the concepts pertaining to responsible leadership.

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership has stimulated a great deal of research in organizational behavior (see e.g., Avolio 1999; Bass 1985; Bass and Avolio 2004; Podsakoff et al. 1996; Podsakoff et al. 1990; Rubin and Munz 2005). The concept originated with Burns’s examination of political leaders (Burns 1978). He describes the transformation process as “leaders and followers [raising] one another to higher levels of morality and motivation” (Burns 1978, p. 20). Transformational leaders recognize their followers’ needs, inspire them and transcend their self-interest to work together towards a common organizational vision (Podsakoff et al. 1990, pp. 108f).

Despite conceptualizing transformational leadership as inherently moral, the ethical component of some of the dimensions has remained controversial. Bass and Steidlmeier (1999) argued that the ethical influence depends on the leader’s motivation. They distinguished pseudo-transformational from authentic transformational leaders.

Responsible leadership is insofar related to transformational leadership in that they share the component of providing individualized support. Such leaders recognize the interests of others, care for their point of view and consider the consequences of actions or decisions with regard to those who could be affected. Additionally, both types of leaders provide an appropriate role model (Bandura 1977, 1986) for followers (and stakeholders). Responsible leaders may occupy such a role by recognizing others and including them in the decision process, as well as in terms of solving (ethical) dilemmas and in producing legitimate solutions.

Yet, there are differences. Transformational leaders lead by advocating a powerful vision of the future, by setting challenging tasks or by proposing intellectually stimulating ideas. In contrast, responsible leaders create arenas where all stakeholders can engage in mutually beneficial dialogues. Responsible leaders thereby address the growing need to balance the interests of different stakeholders, besides the dyadic leader–follower relationship, and set goals through dialogues with the affected constituencies.

In short, on the one hand I expect to find a significant correlation between transformational leadership and responsible leadership conduct. On the other hand, there are important theoretical differences that should lead to empirically distinct constructs.

Hypotheses 1

Transformational leadership is related to yet empirically distinct from responsible leadership.

Ethical Leadership

Brown, Trevino and colleagues have developed a concept of ethical leadership (Brown 2007; Brown and Trevino 2006; Brown et al. 2005; Trevino et al. 2003; Trevino et al. 2000). Trevino et al. (2000, 2003) conducted qualitative interviews in organizations, asking what constitutes ethical leadership. On the one hand, the results revealed personal characteristics related to ethical leadership, which they labeled the moral person dimension. On the other hand, they found aspects of ethical leadership that could be summed up under the term moral manager (Trevino et al. 2000). While the leader as a moral person is characterized as honest and trustworthy, as a fair decision-maker and as someone who cares about people, the leader as a moral manager is a role model who proactively influences followers’ ethical behavior (Brown and Trevino 2006, p. 597).

Responsible leadership overlaps with the moral person dimension of ethical leadership in that responsible leaders care for their employees, think about the consequences of their conduct and discuss the proposed solutions to ethical problems with the affected parties. Responsible leaders, like moral managers, will be viewed as role models by their employees. They set an example of how to do things the right way in terms of producing legitimate decisions and listening to other points of views, weighing and balancing different arguments.

The differences lie in the conceptualization of responsible leadership as a process model based on discursive conflict resolution and deliberative practices, and in the inclusion of internal and external stakeholders into the decision making process. Responsible leaders use their influence to bring all affected parties (not only their employees) together to try to arrive at consensual solutions by weighing and balancing the different interests. In contrast to ethical leadership, they do not reward or punish unethical behavior directly (Brown et al. 2005; Trevino et al. 2000). The discursive process of responsible leadership conduct does not connect leadership to ethical characteristics like trustworthiness or honesty (Trevino et al. 2000, p. 131), but rather treats them as antecedents, as the normative outcome is determined by the rules of the discourse and not by focusing on special virtues.

Thus, it can be hypothesized that ethical leadership and responsible leadership are correlated but not congruent.

Hypotheses 2

Ethical leadership is related to yet empirically distinct from responsible leadership.

Responsible Leadership in Relation to the Hierarchical Position of the Leader, Unethical Behavior and Job Satisfaction

The hypotheses deduced in the following part identify antecedents and outcomes of responsible leadership. They are presented here as they will be examined in the empirical part to test the predictive validity of responsible leadership.

Hierarchical Position

The hierarchical position of the leader should make a difference in terms of the scope and possibilities of responsible leadership conduct. Other research in leadership studies acknowledges the need for a closer examination of the effect of the hierarchical position on leadership and its interrelating variables (Brown and Trevino 2006, pp. 611f), or focuses on specific levels of the hierarchy, for example top-management teams and CEOs in connection with (responsible) leadership (De Hoogh and Den Hartog 2008; Waldman et al. 2006).

The hierarchical position of leaders has an impact on the scope of the leaders’ authority and their access to resources, the frequency of their interactions with stakeholders, the kind of stakeholder engagement, or the scope of their decisions. Leaders further down the hierarchical line will also be restricted in terms of their autonomy in setting up arenas for discursive conflict resolution and in their ability to account for consensual decisions with stakeholders that may to some extent be against the interest of the organization (at least in the short term).

Hypothesis 3

The hierarchical position affects responsible leadership conduct.

Unethical Behavior

Kaptein relates unethical behavior to misconduct where fundamental interests are at stake (Kaptein 2008, p. 980). Unethical behavior can be understood as behavior that is morally unacceptable to the larger community (Jones 1991; as cited in Kaptein 2008, p. 980). From this starting point, Kaptein developed a measure of unethical behavior that drew on business codes as sources for generating the items. The measure examines unethical behavior towards different stakeholder groups (i.e., financiers, customers, employees, suppliers, and society).

Responsible leaders should be able to discourage the unethical behavior of their employees towards all of those stakeholder groups. Responsible leaders can serve as role models in terms of ethical behavior and the inclusion of other points of view or interests. They set an example in that they include the affected stakeholder groups in the decision-making process and try to arrive at mutually beneficial solutions. Such a behavior that tries to solve problems by consensus, without deceiving others or the organization for personal advantage, produces ethically sound solutions that will be an inspiration for employees. As responsible leaders also focus on their employees and include them in difficult decision situations, unethical behavior may come to the forefront more often and be discussed with all parties in order to find alternative solutions.

Hypothesis 4

Responsible leadership will have a negative effect on followers’ unethical behavior.

Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction is a positive emotional attitude that results from a favorable evaluation of one’s work (Brief 1998, p. 10). Employees with high job satisfaction feel comfortable with their work and in their work environment, which results in desirable outcomes for the organization (Brief 1998; Spector 1997).

Responsible leaders foster job satisfaction among the employees by creating an inclusive environment, where the interests of the employees are heard, considered, and discussed. This may cause employees to feel valued, to believe that they have a certain influence on their work environment in that they are heard in decision situations and in that they can bring in their opinions or arguments. Altogether, this should lead to a positive evaluation of their work and to enhanced job satisfaction. Additionally, employees may be more attached to and satisfied with a work environment in which their supervisor acts as a role model for ethical behavior.

Hypothesis 5

Responsible leadership will have a positive effect on followers’ job satisfaction.

In addition, unethical behavior may influence the relationship between responsible leadership and job satisfaction. If employees act unethically, this has a negative effect on the work climate and, subsequently, on the job satisfaction of the work group. Such behavior destroys trust and undermines cooperation and teamwork. If responsible leaders can restrain unethical behavior this will, in turn, increase job satisfaction. Therefore, I assume that there is, apart from the direct effect of responsible leadership on job satisfaction, an indirect effect through the reduction of unethical behavior.

Hypothesis 6

Unethical behavior partially mediates the relationship between responsible leadership and job satisfaction.

Steps in Developing a Scale Measuring Discursive Responsible Leadership

The understanding of responsible leadership as reflected in the definition above offers the possibility to derive an empirical questionnaire scale of discursive responsible leadership. In the following, I will present the development of the discursive responsible leadership scale by describing the operationalization process. The questionnaire scale will then be validated through a series of studies.

Rigorous measurement development is important for social scientific research in order to gain valid and reliable data. I will therefore draw on the steps in validating a scale of responsible leadership according to scientific standards in the field of leadership research (Brown et al. 2005; Liden et al. 2008; Walumbwa et al. 2008). I follow the process proposed by often-cited works in measurement development (Bagozzi 1994a; Hinkin 1995, 1998; Schriesheim et al. 1993; Venkatraman and Grant 1986). The steps for a survey scale development include (1) a rigorous item generation, added if possible by an assessment of the items by experts in the field; (2) verification of content validity (i.e., the extent to which the items really reflect the understanding of responsible leadership as presented in the definition); (3) the internal consistency assessment of the construct; (4) a test of convergent validity; (5) a test of discriminant validity (i.e., the extent to which the concept differs from other concepts, especially from other leadership conceptualizations); and (6) the prediction of nomological (predictive) validity, which can be assessed by empirically confirming theoretical hypotheses. Those steps are reflected in the studies conducted for this paper (see Table 1).

Responsible Leadership in Prior Empirical Research

To guide the item generation, I conducted a review of the literature on empirical measures of either “responsibility” in organizational studies or on leadership concepts pertaining to our understanding of responsible leadership in that they have an ethical or moral component. The definition of responsible leadership, together with this review, was the starting point for the item generation. I report parts of the literature review to present a general overview of the existing instruments and to show how they inspired the generation of items.

First, the instruments measuring responsibility in business organizations will be examined (see exemplary, Pearce and Gregersen 1991; Schlenker et al. 1994; Winter 1991, 1992; Winter and Barenbaum 1985). Thereby, I point out two prominent measurement methods that appear in the literature. On the one hand, questionnaire items measuring responsibility reach back as far as to the Job Diagnostic Survey of Hackman and Oldham (1974, 1975), one of the most frequently used measurements in social science research. The questionnaire contains two items aimed at discovering the responsibility of individuals working in an organization. They very broadly ask respondents if they feel responsible for their job. As they aim directly at assessing the perceived responsibility, I have included them in the original item pool.

On the other hand, some measures of responsibility rely on vignettes. In recent research, De Hoogh and Den Hartog (2008), for example, used a measure of social responsible leadership, drawing on a responsibility measure developed by Winter and Barenbaum (Winter 1991, 1992; Winter and Barenbaum 1985). They identified five categories of responsibility: (1) moral–legal standard of conduct, (2) internal obligation, (3) concern for others, (4) concern about consequences of own action, and (5) self-judgment (Winter 1992). Those categories are used to score running text or other verbal material (e.g., individual thematic apperceptions stories). The categories of moral–legal standard of conduct, concern for others, and concern about consequences are also very strong components of our understanding of responsible leadership. As responsible leadership is based on the moral standards of discourse ethics and deliberative democracy, those leaders show a strong concern for others (i.e., the stakeholders) and think about the consequences of their conduct. Yet, instead of measuring responsible leadership through vignettes, we decided to develop questionnaire items that could be handled more easily and would allow us to refer directly to all stakeholders instead of singling out one stakeholder group for a special scenario.

In the leadership literature, recent efforts have brought forward measures of leadership dealing with issues of ethics and morality. Those instruments and the underlying leadership constructs relate to parts of our understanding of responsible leadership. The concepts include research on transformational leadership theories (Bass 1985; Bass and Avolio 1994), authentic leadership (Avolio and Gardner 2005; Walumbwa et al. 2008), ethical leadership (Brown and Trevino 2006; Brown et al. 2005), as well as servant leadership (Greenleaf 1977; Liden et al. 2008). The theoretical similarities and differences between the different leadership approaches and responsible leadership have been presented in the work on responsible leadership by Patzer and colleagues (Patzer and Scherer 2010; Voegtlin et al. 2011), as well as partly in the presented literature review. I analyzed the items of these leadership scales, and adapted and reformulated those parts of the items that related to the theoretical similarities between those leadership concepts and the responsible leadership concept. Those were added to the preliminary item pool.

Item Generation and Content Validation

Starting from the definition of responsible leadership and from the review of the literature dealing either with leadership and ethics or with responsibility measures, an initial pool of 46 items was retrieved (first development step; see Table 1). In an iterative process with members of the institute and colleagues dealing with the topic of responsible leadership, the initial pool of items was reduced and partly reformulated. We focused on the extent to which the items could address parts of the definition of responsible leadership. Those items that did not fit well were deleted. The result was a preliminary scale of 18 items. The items were formulated in such a way that employees would have to rate their direct supervisor. I decided to measure responsible leadership via other-reports, since this topic touches the sphere of ethics, where self-reports can lead to social desirability biases (Brown et al. 2005, p. 121; Kaptein 2008, p. 986).

Study 1

The preliminary item pool was presented to a student sample. Fourteen students attending a public university in Switzerland participated in the study to estimate the content validity. The participants received a questionnaire with 18 items referring to responsible leadership and the items of the ethical and transformational leadership scales. The items were randomly ordered. They also received the definitions of each leadership construct with an absolute number of items per construct. They were then instructed to assign each item to one of the leadership constructs. This step helps to ensure a preliminary analysis of the content adequacy and the distinctiveness to related leadership constructs.

Hinkin points out that a student sample is appropriate for this task, because it poses a cognitive challenge which can be solved without referring to prior work experience (Hinkin 1995, p. 971). He proposes that those items that were assigned to the proper construct by 80% of the respondents can be regarded as possessing content validity (Hinkin 1995, p. 970). As this first step can be regarded here as a preliminary study with relatively few participants, responsible leadership items with a consent rate of 70% were considered acceptable and were thus included in the following studies. Those items that did not meet the criteria were reformulated or deleted.

Study 2

The retrieved items of the prior study, added by revised and reformulated items (a total of 21 items), were then presented to experts in the field of leadership and/or CSR. The expert rating is a further step in establishing content validity (Schriesheim et al. 1993). These experts included internationally renowned researchers in the fields of leadership, CSR and stakeholder management, or organization studies, a practitioner working in leadership training and development, as well as doctoral students working in those fields. Altogether 13 experts evaluated the items (see Table 1). They were presented with the items and the definition of responsible leadership. In an iterative process, I discussed the items with them. The items were assessed according to their content adequacy (i.e., how well they reflect parts of the definition of responsibility) and how well all items together cover the full domain of responsible leadership conduct. In addition, we ensured that the items were formulated according to common suggestions of constructing questionnaires (e.g., being brief, relevant, unambiguous, specific, and objective) (see e.g., Peterson 2000; Schnell et al. 1999). At the end of this evaluation, a pool of 19 items remained.

One of the experts suggested introducing the scale with a definition of the term “stakeholder” as well as with questions regarding the frequency of interaction with different stakeholder groups (see final scale in Appendix). This would familiarize participants with the term “stakeholder” and give the researcher using the scale insight into the stakeholder groups with which the leader interacts. The questions regarding the frequency of stakeholder interaction could be useful in the assessment of the frequency or pattern of stakeholder engagement, as well as for comprehending the effects of leader–stakeholder interactions on other variables (see limitations for possible restrictions of such an approach). It was decided to measure the scale by a 5-point rating-scale response format, ranging from (1) not at all to (5) frequently, if not always.

The procedure presented in study 2 was an iterative process, as it took place parallel to studies 1 and 3. After each point in the development or validation of items, all of the results were cross-validated with some of the experts, leading to new or reformulated items. The main exchange with most of the experts, however, took place after study 1.

Exploratory Factor Analysis and Internal Consistency

The empirical validation started with an exploratory approach. In this step the initial items were reduced and validated to a final scale of discursive responsible leadership. Therefore, I conducted an exploratory factor analysis (Fabrigar et al. 1999). The exploratory factor analysis aims at discovering an empirical connection among variables. In this case, it was looked at which items of the initial item pool best represented the underlying construct of responsible leadership. This helps to decide which variables are truly relevant for explaining responsible leadership and to reduce the item pool to the main variables. Additionally, the internal consistency of the extracted items was estimated by calculating Cronbach’s alpha (Bagozzi 1994a).

Study 3

The 19 items extracted from study 2 were administered to a sample of 139 students of a public university in Switzerland. Fifty-seven percent of the sample consisted of women. The average age of the participants was 24.4 years; they had already been studying for 7.3 semesters on average and had a mean of 4.3 years of working experience (see Table 1). In Switzerland we had the advantage that most of the students also work or hold internship, either to earn money for their academic studies or to advance their career opportunities. For the empirical analysis, only those participants were selected that had more than 1 year of work experience. This resulted in a final sample of 128 students.

I conducted the exploratory factor analysis using principle axis factoring. The factors were allowed to correlate by letting them rotate using direct oblimin rotation (Fabrigar et al. 1999). The results showed four factors with eigenvalues greater than one. The scree-plot indicated a steep drop after the first factor, pointing to a one-factor solution (Kaptein 2008, p. 987). The eigenvalue of the first factor was 8.71, explaining 46% of the variance. The measure of sampling adequacy (MAS) value for the exploratory analysis was 0.91 (values ≥0.80 are desirable; Backhaus et al. 2006).

By analyzing the factor loadings, those items that did not load strongly on the primary factor (factor loading above 0.50), or cross-loaded on one of three minor factors (loading on secondary factor above 0.20) were excluded. This reduced the initial 19 items to 14. All of the remaining items showed factor loadings higher than 0.60 for the primary factor. In discussions with experts, those items that were confusing or redundantly worded were sorted out (cf., Brown et al. 2005, p. 124). As we aimed for a single factor solution, the extracted scale of responsible leadership resulted in four items. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for the four items. The scale proved to be internally consistent (α = 0.81). The results for the final items retrieved from the exploratory factor analysis are reported in Table 2.

As this step was conducted in conjunction with further discussions with experts and members of the institute working on the same topic, we had a long discussion after the accomplishment of the exploratory factor analysis that resulted in the consensus that one more item should be added to reflect the full content domain of responsible leadership conduct. This item was “my direct supervisor tries to achieve a consensus among the affected stakeholders.” This final step in discursive conflict resolution, an essential part of responsible leadership, was until now only partially reflected through the other items. After adding the item I arrived at a final discursive responsible leadership scale consisting of five items.

Convergent, Discriminant, and Predictive Validity

A central aspect of construct validation includes testing convergent and discriminant validity (Bagozzi 1994a; Hinkin 1995; Venkatraman and Grant 1986). “Convergent validity is the degree to which multiple attempts to measure the same concept are in agreement. […] Discriminant validity is the degree to which measures of different concepts are distinct” (Bagozzi 1994a, p. 20). I could not measure convergent validity directly by validating the responsible leadership construct with other existing instruments, as this is a theoretically new construct. It could, however, be tested for the dimensionality of the construct by using confirmatory factor analysis. Discriminant validity can be determined by showing that the construct of interest is empirically distinct from other constructs (for similar approaches to construct validity, see e.g., Brown et al. 2005; Kaptein 2008; Walumbwa et al. 2008). Finally, the predictive (nomological) validity was tested. The predictive validity aims at how well the focal construct can predict or is predicted by other measures from which a relationship can be theoretically deduced (Bagozzi 1994a).

In order to establish construct and predictive validity, I conducted two further studies (studies 4 and 5). In these studies I used structural equation modeling (Bagozzi 1994b). For thresholds in estimating the goodness of fit of a structural equation model, I draw on often cited and recommended standards (see e.g., Byrne 2001; Hu and Bentler 1999). The thresholds are reported in brackets after each fit index. As test statistics, I decided to report the Chi-Square test statistic (χ2), additionally divided by degrees of freedom (χ2/df ≤ 2.5), the Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI ≥ 0.95), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI ≥ 0.95), the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR ≤ 0.08), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA ≤ 0.06).

Before studies 4 and 5 were conducted, the discursive responsible leadership questionnaire was translated into German (see Appendix for the final English and German discursive responsible leadership scale). I used a double blind back-translation strategy. The questionnaire was first translated from English to German, and then translated German to English by different people. In cases where the meaning of the translations differed, both translators had to agree on a solution which they thought could best capture the original English sense of the item.

Study 4

As I added an additional item to the final scale of discursive responsible leadership that was not part of the exploratory factor analysis, another study with students from the same University was initiated to validate the new item before testing the scale in a final sample of the working population (see summary in Table 1).

The questionnaire, including the final five items of the responsible leadership scale, was distributed to 75 students during two lectures. Among these students, 57% were male. They were on average 21.7 years old. We asked the participants to specify the number of years that they had worked with their supervisor. This resulted in a mean of 1.4 years. After deleting the missing values, the final sample contained 69 responses.

I used confirmatory factor analysis to analyze the convergent validity of the five items of the responsible leadership scale. The scale was modeled with structural equations, using one factor to explain the variance in all five of the items. The estimation was done by maximum likelihood. The results showed very good fit statistics, with χ2/df = 1.300; NNFI = 0.977; CFI = 0.989; SRMR = 0.036, except for the RMSEA. The RMSEA value of 0.066 was slightly higher than the threshold of 0.06 mentioned by Hu and Bentler (1999); yet it still points to a reasonable model fit (values <0.08 or between 0.08 and 0.10 were suggested as reasonable model fit; see Byrne 2001, p. 85). All factor loadings were significant and reported strong relations to the underlying construct of responsible leadership (see Table 2). The discursive responsible leadership scale demonstrated high reliability (α = 0.84). These results confirmed the theoretical considerations for the 5-item scale derived from the exploratory factor analysis.

Study 5

For the final study, the discursive responsible leadership survey was distributed among a diverse sample of the working population in Germany. Collecting data by using a panel survey has the advantage of circumventing the reluctance of organizations granting access for research on delicate (ethical) topics. In addition, it may enhance the perceived anonymity of the respondents in the sense that it reduces the threat that someone could trace their answers back to their supervisors or organization, and thus possibly deter them from answering in a socially desirable manner (see e.g., Kaptein 2008, pp. 986f; for general aspects of social desirability in ethics research, see Fernandes and Randall 1992). Limits of a panel survey may be that the participants represent a respondent group that is more willing to answer questions (as they voluntarily participate and stay in a panel) and therefore may not be representative of the general population.

The participants were recruited online and had to answer a Web-based questionnaire. The sampling was carried out by a German company (www.webfrager.de), which conducts professional panel surveys. The company recruits its panel members by drawing on the standards of the German ADM Design. The ADM Design is used in professional survey research in Germany, where random sampling is achieved by a three-stage process: first, randomly selected electoral districts; second, households, accessed by random walk; and finally, a person within the household chosen randomly from among the residents (Schnell et al. 1999, pp. 264ff). The company provided the participants with the link to the Web-based questionnaire.

The survey was online for 2 weeks in December 2009. Altogether, 187 people were invited to complete it. The company organizing the panel offered the respondents an incentive to participate in the survey. Of those participants, 150 completed the questionnaire, which resulted in a response rate of 80%.Footnote 1 After deleting the responses of people who were not currently working, as well as the cases with missing values in answering the responsible leadership scale, the final sample contained 128 answers.

More than half of the participants (53%) of the final sample were male. The average age was 44 years. Company tenure ranged from less than 1 year (6%) to over 35 years (5%) with the majority of respondents working between 1 and 5 years (29%) for their organization. Fifty-five percent had worked less than 5 years under their current supervisor, 29% had worked for 5 to 10 years, and 17% for 11 to 30 years with their supervisor. Half of the respondents (50%) were employed by multinational corporations, while the other half worked for small and medium enterprises. Fifty-eight percent were employees without direct reports at the operating level, 21% were lower management, 16% middle management, and 5% were from top management.

The confirmatory factor analysis showed a very good model fit for the one-factor solution of the discursive responsible leadership scale (χ2/df = 1.197; NNFI = 0.996; CFI = 0.998; SRMR = 0.015; and RMSEA = 0.039) with significant factor loadings for all five items (see Table 2). The results for the final scale of discursive responsible leadership again reported a high internal consistency (α = 0.94). The factor loadings of the CFA in study 5 are slightly higher than in the previous two studies. This may be due to the more experienced sample of the working population, compared to the student samples. Even though only those students with work experience were considered for studies 3 and 4, their interaction with the supervisor may be quite irregular (i.e., they may work only once a week; or only during semester breaks; or were not working at the time of the survey and had to draw on past experiences). Therefore, they may have more difficulty in observing and evaluating the respective leadership behavior as clearly as the sample drawn from the working population did.

Following the confirmatory factor analysis, I tested for the discriminant validity by comparing responsible leadership to the related leadership constructs of ethical and transformational leadership. Before starting the analysis, those cases with missing values for transformational and ethical leadership were deleted.

Ethical leadership was measured using the 10-item ethical leadership scale developed by Brown and colleagues (Brown et al. 2005) (α = 0.95). Transformational leadership was adapted from Podsakoff et al. (1996; Rubin and Munz 2005) (α = 0.92). Starting from the theoretical considerations, I expected ethical and transformational leadership to be significantly related to responsible leadership, yet empirically distinct from it (Hypotheses 1 and 2). The correlations reported in Table 3 showed such a significant relation between responsible leadership and the other two constructs.

To establish discriminant validity and to demonstrate the distinction among ethical, transformational, and responsible leadership, I tested in a first step if the average variance extracted estimate of the factor in question (responsible leadership) is greater than the squared estimated correlation between the latent factor and the latent factors that should be discriminant from it (Fornell and Larcker 1981, pp. 45f; Netemeyer et al. 1990; Walumbwa et al. 2008). The average variance extracted estimate of the responsible leadership factor was 0.72 (0.62 for ethical leadership and 0.73 for transformational leadership), whereas the squared estimated correlation between responsible and ethical leadership was 0.30, and between responsible and transformational leadership it was 0.41; this was indicative of distinct leadership constructs.

In a second step, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted, modeling responsible and ethical leadership as two distinct factors. A first model where both factors were allowed to correlate freely (unconstrained model) was tested against a model where the correlation between the factors was set to 1 (constrained model). A significantly lower χ2 for the unconstrained model can be regarded as evidence of discriminant validity (Venkatraman 1989; Walumbwa et al. 2008, pp. 108ff). The results showed a better model fit for the unconstrained model (for the fit statistics, see Table 3) with a significantly lower χ2 value (∆χ2 = 23.362; ∆df = 1; p < 0.001), thus supporting discriminant validity. The same was done to test the relation between responsible and transformational leadership. Again, the χ2 value (∆χ2 = 29.040; ∆df = 1; p < 0.001) was significantly lower for the unconstrained model, confirming the distinction between transformational and responsible leadership. Yet, the fit statistics for the unconstrained model were slightly above or below the required thresholds (see Table 3). To cross-validate these findings, I conducted an exploratory factor analysis including all leadership items. The second factor extracted was defined by the five items of the responsible leadership scale (eigenvalue 2.637; factor loadings of the DRL items: 0.388; 0.425; 0.463; 0.454; 0.471).

Taken together, the results showed that the responsible leadership construct is discriminant from both ethical and transformational leadership. Table 3 summarizes these results.

Finally, I addressed the predictive validity of discursive responsible leadership. The effect of the hierarchical position on responsible leadership behavior was examined (Hypothesis 3). Further, I tested the extent to which responsible leadership conduct can reduce followers’ unethical behavior (Hypothesis 4), and increase their job satisfaction (Hypothesis 5). In addition, unethical behavior was hypothesized to partially mediate the relationship between responsible leadership and job satisfaction (Hypothesis 6). All hypotheses were tested within one structural equation model.

To measure the hierarchical position, the participants were directly asked to indicate if they belonged to the operating level, the lower management, middle management, or top management. This also defined the position of their direct supervisor. Unethical behavior was measured with the scale developed by Kaptein (2008). I examined the part on unethical behavior towards employees (α = 0.90). The job satisfaction scale was a three-item scale taken from Brayfield and Rothe (1951) (α = 0.84).

The results showed very good fit statistics of the overall model (χ2/df = 1.305; NNFI = 0.970; CFI = 0.976; SRMR = 0.058; and RMSEA = 0.053). The hypothesized relationships were all significant. I found a positive relationship between the hierarchical level and responsible leadership (r = 0.25; p < 0.01). Leaders in higher hierarchical positions were perceived more often as responsible leaders, thus confirming Hypothesis 3. Responsible leadership in turn had a significant effect on job satisfaction (r = 0.28; p < 0.01), and on reducing the unethical behavior towards employees (r = −0.14; p < 0.1). That means that responsible leaders are able to diminish unethical behavior towards fellow co-workers in their organization and to enhance the job satisfaction of employees (confirming Hypotheses 4 and 5). Additionally, the effect on job satisfaction was partially mediated by the observed unethical behavior (r = −0.37; p < 0.01) as predicted in Hypothesis 6.

Apart from that, I moderated also for the frequency of interaction with employees among responsible leadership, unethical behavior, and job satisfaction. The moderation (Aiken and West 1996; Baron and Kenny 1986) was tested by entering the product terms “responsible leadership” and “interaction with employees” in the second step of a regression analysis, after examining the direct effect of responsible leadership on unethical behavior in the first step. Before building the product and before conducting the analysis all variables were mean centered (Aiken and West 1996). The same was done for the job satisfaction. The results showed an effect of the product term on unethical behavior, as well as on job satisfaction over and above that of responsible leadership conduct alone (unethical behavior: ∆R 2 = 0.04; β = −0.38; p < 0.05; job satisfaction: ∆R 2 = 0.04; β = 0.39; p < 0.05), thus pointing to a moderation due to the frequency of interaction.

Altogether, the theoretical hypotheses could be empirically validated, pointing towards the predictive validity of the discursive responsible leadership scale (for a summary of the validation steps, see Table 1).

Conclusion

Responsible leadership transcends the dyadic leader–follower model to a leader–stakeholder interaction (Maak 2007; Maak and Pless 2006b). The understanding of leadership as presented here refers to leadership conduct in the form of discursive conflict resolution and deliberative practices (Patzer 2009; Patzer and Scherer 2010). Responsible leadership is still based on an influence process (“influence” is part of most standard definitions of leadership, see e.g., Rost 1991; Yukl 2006), with the difference that responsible leaders first think about consequences of their decisions for the (possibly) affected parties, and then subsequently use their influence to include those affected stakeholders in the decision making process and try to solve (morally) complex situations in a consensus among all affected parties. Responsible leadership is thereby based on the ideal of discourse ethics and can be understood as a continuum from the leader acting solely on a strategic-instrumental rational to the ideal responsible leader (for the two different positions, see exemplary, Waldman and Galvin 2008). The authors forwarding this concept propose that such an understanding of responsible leadership can address the challenges of globalization better than existing leadership concepts (see also, Voegtlin et al. 2011). A deeper examination of this proposal would require an empirical instrument.

In this article I developed such a scale of discursive responsible leadership to capture the phenomenon empirically. The scale was validated through different studies. The results showed a scale of discursive responsible leadership that had good psychometric properties, correlated with theoretically related constructs (ethical and transformational leadership), yet were empirically distinct from those, and could predict theoretical hypotheses. Thus, the studies revealed a scale of discursive responsible leadership that showed a one-dimensional construct with high internal consistency, as well as discriminant, and predictive validity.

Several other conclusions can be drawn from the results of Hypotheses 3 to 6. The positive relationship in Hypothesis 3 indicated that responsible leadership is dependent on the hierarchical level. This is mostly due to the limited possibilities of lower level supervisors to interact with different stakeholder groups that could be affected by their decisions. One practical implication that follows from this is that the organization should facilitate the possibility of stakeholder interaction for leaders and employees further down the hierarchical line to strengthen responsible leadership conduct.

The results of testing Hypothesis 4 showed that responsible leadership can reduce unethical behavior among the primary stakeholders: the employees. Responsible leaders as positive role models talk with their employees, include them in decision-making and discuss difficult (ethical or moral) problems with them to come to satisfying (ideally consensual) solutions, thus reducing the possibility of unethical behavior and providing an example to follow in terms of ethical conduct.

Hypothesis 5 showed that the job satisfaction of the employees is positively related to their direct supervisor’s responsible leadership conduct. Job satisfaction is an important dimension, one that has many positive effects upon an organization (Brief 1998; Spector 1997). The effect of responsible leadership on job satisfaction was partly mediated by the observed unethical behavior (Hypothesis 6). Thus, responsible leaders have an additional, indirect effect on job satisfaction by helping to create a more ethical work environment.

The strength between unethical behavior and responsible leadership, and between job satisfaction and responsible leadership, respectively, is further moderated by the frequency of interaction between a supervisor and employees. The results revealed by the moderation may not be very surprising. Yet, we can draw further inferences if we relate this result to the satisfaction of other stakeholders groups with focal persons in an organization. I propose that responsible leadership is also able to foster satisfactory (and mutually beneficial) relationships with stakeholder groups inside and outside the organization, depending on the extent of responsible leadership conduct and on the frequency of interaction with those stakeholder groups.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

It was decided to introduce the discursive responsible leadership scale with a definition of the term stakeholder and with a list of stakeholders where respondents can rate how often their supervisor interacts with them. The definition and the list contain possible limitations, in that first, the participants may be biased to think only of those stakeholders mentioned, and second, that adding 11 questions to a scale of five items makes the scale considerably longer (Molenaar 1982; Peterson 2000). The first limitations can to a certain extent be alleviated as we tried to present a fairly comprehensive list of stakeholders that leaders in organizations will have to deal with and as we encourage the participants to think of further stakeholders themselves by presenting the option of filling in “other” stakeholders. Additionally, we cannot assume that every employee is familiar with the term stakeholder. Thus, the definition may help respondents with an ambiguous term. As for the second limitation, the additional questions regarding the stakeholders may be regarded as optional for future researchers, who might balance the length of the questionnaire against possible insights that may be gained by the additional questions.

Throughout the studies there was only one sample of the working population to test the scale, even though the student samples consisted of participants with actual or prior work experience. Additionally, the studies were focused on Switzerland and Germany. To further validate the scale, samples of leaders working in diverse organizations throughout different countries should be examined.

The studies for the item generation and the questionnaire construction were conducted to avoid systematic measurement errors in social scientific research according to common recommendations (see e.g., Bagozzi 1994a; Podsakoff et al. 2003). Yet, a further limitation could be a common method bias due to measuring the independent and the dependent variables in study 5 with the same instrument (Podsakoff et al. 2003). This should not affect the results of the validation of the scale, apart from a potential method bias for the predictive validity. Further tests should try to replicate these findings.

Finally, I aimed here for a one-dimensional solution of the discursive responsible leadership scale to focus on the discourse ethical process. This allows setting the scale clearly apart from other constructs, and the five-item solution can be used very easily and efficiently. Yet, as this was a first attempt to measure responsible leadership, additional research could expand the scale to include further dimensions of responsible leadership conduct.

Further, the item development was based partly on existing items, amended by items developed directly from the definition of responsible leadership. Even though most of the items taken from existing scales were dropped during the validation process, we did not cross-validate the remaining items through cognitive interviews. Additionally, there are limitations to the ideal of responsible leadership conduct in terms of time and resource constraints in daily business. Future research to expand the construct could thus include cognitive interviews in order to understand what question people think they are answering and what the limitations of the ideal of responsible leadership may be.

Subsequently, future research can use the discursive responsible leadership scale to advance the knowledge in the field. By testing the antecedents and outcomes of responsible leadership, our understanding of the phenomenon of responsible leadership could be extended. One goal should be to prove the nomological validity of discursive responsible leadership, especially in predicting and positively addressing the challenges of globalization. In relation to this, it could, for example, be looked at as to how responsible leadership conduct can build and secure the (moral) legitimacy of an organization, create (social) innovation or trustful relationships with stakeholders.

Notes

This is not the original response rate that relates all those recruited for the panel to the 150 persons answering the questionnaire; this would be 0.80 times the response rate of the initial panel recruitment.

References

Agle, B. R., Donaldson, T., Freeman, R. E., Jensen, M. C., Mitchell, R. K., & Wood, D. J. (2008). Dialogue: Toward superior stakeholder theory. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18(2), 153–190.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1996). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Avolio, B. J. (1999). Full leadership development: Building the vital forces in organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Avolio, B. J., & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315–338.

Backhaus, K., Erichson, B., Plinke, W., & Weiber, R. (2006). Multivariate data analysis: An application oriented introduction [Multivariate Datenanalyse: Eine anwendungsorientierte Einführung] (11th ed.). Berlin: Springer.

Bagozzi, R. P. (1994a). Measurement in marketing research: Basic principles of questionnaire design. In R. P. Bagozzi (Ed.), Principles of marketing research (pp. 1–49). Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Bagozzi, R. P. (1994b). Structural equation models in marketing research: Basic principles. In R. P. Bagozzi (Ed.), Principles of marketing research (pp. 317–385). Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Engelwood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Engelwood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2004). Multifactor leadership questionnaire: Manual leader form, rater, and scoring key for MLQ (Form 5x-Short). Redwood City: Mind Garden.

Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 181–217.

Beck, U. (2000). What is globalization?. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bies, R. J., Bartunek, J. M., Fort, T. L., & Zald, M. N. (2007). Corporations as social change agents: Individual, interpersonal, institutional, and environmental dynamics. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 788–793.

Brayfield, R. H., & Rothe, H. F. (1951). An index of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 35, 307–311.

Brief, A. P. (1998). Attitudes in and around organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Brown, M. E. (2007). Misconceptions of ethical leadership: How to avoid potential pitfalls. Organizational Dynamics, 36(2), 140–155.

Brown, M. E., & Trevino, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Brown, M. E., Trevino, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

Crane, A., McWilliams, A., Matten, D., Moon, J., & Siegel, D. S. (2008). The Oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

De Hoogh, A. H. B., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2008). Ethical and despotic leadership, relationships with leader’s social responsibility, top management team effectiveness and subordinates’ optimism: A multi-method study. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(3), 297–311.

Doh, J. P., & Stumpf, S. A. (2005a). Handbook on responsible leadership and governance in global business. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Doh, J. P., & Stumpf, S. A. (2005b). Towards a framework of responsible leadership and governance. In J. P. Doh & S. A. Stumpf (Eds.), Handbook on responsible leadership and governance in global business (pp. 3–18). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272–299.

Fernandes, M. F., & Randall, D. M. (1992). The nature of social desirability response effects in ethics research. Business Ethics Quarterly, 2(2), 183–205.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 18(1), 39–50.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman.

Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant leadership. New York: Paulist Press.

Habermas, J. (1993). Remarks on discourse ethics. In J. Habermas (Ed.), Justification and application (pp. 19–111). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (1998). Between facts and norms: Contributions to a discourse theory of law and democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Habermas, J. (2001a). The inclusion of the other: Studies in political theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (2001b). The postnational constellation: Political essays. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1974). The job diagnostic survey: An instrument for the diagnosis of jobs and the evaluation of job redesign projects (Technical Report No. 4). New Haven: Yale University, Department of Administrative Science.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 159–170.

Hinkin, T. R. (1995). A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. Journal of Management, 21(5), 967–988.

Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1, 104–121.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure modeling: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55.

Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395.

Kaptein, M. (2008). Developing a measure of unethical behavior in the workplace: A stakeholder perspective. Journal of Management, 34(5), 978–1008.

Laplume, A. O., Sonpar, K., & Litz, R. A. (2008). Stakeholder theory: Reviewing a theory that moves us. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1152–1189.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H., & Henderson, D. (2008). Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadership Quarterly, 19(2), 161–177.

Maak, T. (2007). Responsible leadership, stakeholder engagement, and the emergence of social capital. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(4), 329–343.

Maak, T., & Pless, N. (2006a). Responsible leadership. New York: Routledge.

Maak, T., & Pless, N. (2006b). Responsible leadership: A relational approach. In T. Maak & N. Pless (Eds.), Responsible leadership (pp. 33–53). New York: Routledge.

Matten, D., & Crane, A. (2005). Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 166–179.

Molenaar, N. J. (1982). Response-effects of “formal” characteristics of questions. In W. Dijkstra & J. Van der Zouwen (Eds.), Response behaviour in the survey-interview (pp. 49–89). London: Academic Press.

Netemeyer, R. G., Johnston, M. W., & Burton, S. (1990). Analysis of role conflict and role ambiguity in a structural equations framework. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(2), 148–157.

Palazzo, G., & Scherer, A. G. (2006). Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 66(1), 71–88.

Palazzo, G., & Scherer, A. G. (2008). The future of global corporate citizenship: Toward a new theory of the firm as a political actor. In A. G. Scherer & G. Palazzo (Eds.), Handbook of research on global corporate citizenship (pp. 577–590). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Patzer, M. (2009). Leadership and its responsibility under the condition of globalization [Führung und ihre Verantwortung unter den Bedingungen der Globalisierung. Ein Beitrag zu einer Neufassung vor dem Hintergrund einer Republikanischen Theorie der Multinationalen Unternehmung] (Patzer Verlag, Berlin/Hannover).

Patzer, M., & Scherer, A. G. (2010). Global responsible leadership: Towards a political conception. In 26th EGOS Colloquium, Lisbon.

Pearce, J. L., & Gregersen, H. B. (1991). Task interdependence and extrarole behavior: A test of the mediating effects of felt responsibility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(6), 838–844.

Peterson, R. A. (2000). Constructing effective questionnaires. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Pless, N. (2007). Understanding responsible leadership: Role identity and motivational drivers. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(4), 437–456.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Bommer, W. H. (1996). Transformational leader behaviors and substitutes for leadership as determinants of employee satisfaction, commitment, trust, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Management, 22(2), 259–298.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Jeong-Yeon, L., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Moorman, R. H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 1(2), 107–142.

Post, J. E., Preston, L. E., & Sachs, S. (2002). Redefining the corporation: Stakeholder management and organizational wealth. Stanford: Stanford Business Books.

Rost, J. (1991). Leadership for the twenty-first century. New York: Praeger.

Rubin, R. S., & Munz, D. C. (2005). Leading from within: The effects of emotion recognition and personality on transformational leadership behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 845–858.

Scherer, A. G., & Palazzo, G. (2007). Toward a political conception of corporate social responsibility: Business and society seen from a Habermasian perspective. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1096–1120.

Scherer, A. G., & Palazzo, G. (2008a). Globalization and corporate social responsibility. In A. Crane, A. McWilliams, D. Matten, J. Moon, & D. S. Siegel (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility (pp. 413–431). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scherer, A. G., & Palazzo, G. (2008b). Handbook of research on global corporate citizenship. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Scherer, A. G., Palazzo, G., & Baumann, D. (2006). Global rules and private actors: Toward a new role of the transnational corporation in global governance. Business Ethics Quarterly, 16(4), 505–532.

Scherer, A. G., Palazzo, G., & Matten, D. (2009). Globalization as a challenge for business responsibilities. Business Ethics Quarterly, 19(3), 327–347.

Schlenker, B. R., Britt, T. W., Pennington, J., Murphy, R., & Doherty, K. (1994). The triangle model of responsibility. Psychological Review, 101(4), 632–652.

Schnell, R., Hill, P. B., & Esser, E. (1999). Methods in empirical social research [Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung]. Munich: Oldenbourg Verlag.

Schriesheim, C. A., Powers, K. J., Scandura, T. A., Gardiner, C. C., & Lankau, M. J. (1993). Improving construct measurement in management research: Comments and a quantitative approach for assessing the theoretical content adequacy of paper-and-pencil survey-type instruments. Journal of Management, 19(2), 385–417.

Spector, P. E. (1997). Job satisfaction: Application, assessment, causes, and consequences. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Stansbury, J. (2009). Reasoned moral agreement: Applying discourse ethics within organizations. Business Ethics Quarterly, 19(1), 33–56.

Trevino, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. (2003). A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human Relations, 56(1), 5–37.

Trevino, L. K., Hartman, L. P., & Brown, M. (2000). Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. California Management Review, 42(4), 128–142.

Venkatraman, N. (1989). Strategic orientation of business enterprises: The construct, dimensionality, and measurement. Management Science, 35(8), 942–962.

Venkatraman, N., & Grant, J. H. (1986). Construct measurement in organizational strategy research: A critique and proposal. Academy of Management Review, 11(1), 71–87.

Voegtlin, C., Patzer, M., & Scherer, A. G. (2011). Responsible leadership in global business: A new approach to leadership and its multi-level outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-0952-4.

Waldman, D. A., & Galvin, B. M. (2008). Alternative perspectives of responsible leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 37(4), 327–341.

Waldman, D. A., & Siegel, D. (2008). Defining the socially responsible leader. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(1), 117–131.

Waldman, D. A., Siegel, D. S., & Javidan, M. (2006). Components of CEO transformational leadership and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Management Studies, 43(8), 1703–1725.

Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34(1), 89–126.

Winter, D. G. (1991). A motivational model of leadership: predicting long-term management success from TAT measures of power motivation and responsibility. The Leadership Quarterly, 2(2), 67–80.

Winter, D. G. (1992). Responsibility. In C. P. Smith (Ed.), Motivation and personality: Handbook of thematic content analysis (pp. 500–511). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Winter, D. G., & Barenbaum, N. B. (1985). Responsibility and the power motive in women and men. Journal of Personality, 53(2), 335–355.

Yukl, G. (2006). Leadership in organizations (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Discursive Responsible Leadership—Final Scale English

The following section often refers to the term “stakeholders”. Stakeholders are defined as the individuals and constituencies that can affect or are affected by your organization. Examples of stakeholders are, e.g., shareholders or investors, employees, customers and suppliers, the local community, the society or the government.

If the questionnaire items ask for the relevant stakeholders in relation to your superior’s actions or decisions, think about the stakeholders your supervisor interacts with (most frequently).

Please indicate how often your supervisor interacts with which stakeholder groups:

Not at all | Once in a while | Sometimes | Fairly often | Frequently, if not always | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

Customers | |||||

Employees | |||||

Employees or management of joint venture partners and alliances | |||||

Labor unions | |||||

Local community representatives (e.g. societies, associations, the church) | |||||

Non-governmental organizations (e.g., social or environmental activist groups) | |||||

Shareholders or investors | |||||

State institutions or regulatory authorities (this can reach from interactions with the government officials to interactions with the local city administration) | |||||

Suppliers | |||||

Top management | |||||

Other (including space to fill in): |

My direct supervisor…

Not at all | Once in a while | Sometimes | Fairly often | Frequently, if not always | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

…demonstrates awareness of the relevant stakeholder claims | |||||

…considers the consequences of decisions for the affected stakeholders | |||||

…involves the affected stakeholders in the decision making process | |||||

…weighs different stakeholder claims before making a decision | |||||

…tries to achieve a consensus among the affected stakeholders |

Diskursiv Verantwortungsvolle Führung—Final Scale German

Der folgende Abschnitt bezieht sich oft auf den Begriff “Stakeholder”. Stakeholder sind definiert als die Individuen oder Gruppen, die durch ihre Handlungen die Organisation betreffen oder die von den Handlungen der Organisation betroffen sind.

Beispiele für Stakeholder sind die Shareholder oder Investoren, die Mitarbeiter, die Kunden und Zulieferer, die lokale Gemeinde, die Gesellschaft oder die Regierung.

Wird in den Fragebogen-Items nach den relevanten Stakeholdern in Verbindung mit dem Handeln oder den Entscheidungen Ihres Vorgesetzten gefragt, denken Sie an die Stakeholder mit denen Ihr Vorgesetzter (am häufigsten) interagiert.

Bitte geben Sie an, wie häufig ihr Vorgesetzter mit welcher Stakeholder-Gruppe interagiert:

Niemals | Selten | Manchmal | Häufig | Extrem häufig, wenn nicht immer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

Kunden | |||||

Mitarbeiter | |||||

Mitarbeiter oder Manager von Joint Venture Partnern oder Allianzen | |||||

Gewerkschaften | |||||

Repräsentanten der lokalen Gemeinde (z.B. Vereine, Verbände, die Kirche) | |||||

Nicht-Regierungs-Organisationen (z.B. Sozial- oder Umweltgruppen) | |||||

Shareholder oder Investoren | |||||

Staatliche Institutionen oder Regulierungsbehörden (dies kann von der Interaktion mit offiziellen Regierungsvertretern bis zur Interaktion mit der lokalen Stadtadministration reichen) | |||||

Zulieferer | |||||

Top Management | |||||

Andere: |

Mein direkter Vorgesetzter…

Niemals | Selten | Manchma | Häufig | Extrem häufig, wenn nicht immer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

… zeigt, dass er/sie sich der Ansprüche relevanter Stakeholder bewusst ist | |||||

…berücksichtigt die Konsequenzen von Entscheidungen für die betroffenen Stakeholder | |||||

…bezieht die betroffenen Stakeholder in den Entscheidungsprozess mit ein | |||||

…wägt die verschiedenen Stakeholderansprüche ab, bevor er/sie eine Entscheidung fällt | |||||

…versucht unter den betroffenen Stakeholdern einen Konsens zu erzielen |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article