Abstract

Drawing upon social identity theory, we investigate how subordinates’ perceived insider status within an organization may relate to abusive supervision and their proactive behavior. In addition, based on social role theory, we examine the moderating role of subordinate gender in this framework. Using a sample of 350 supervisor–subordinate dyads from an IT group corporation, we found that abusive supervision was negatively related to subordinates’ proactive behavior, and that subordinates’ perceived insider status mediated this relationship. Results also show that subordinate gender moderated the negative relationship between abusive supervision and perceived insider status, such that it was stronger for female than for male subordinates. This study highlights the pivotal roles of subordinates’ gender and identification in the consequences of abusive supervision at work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Seventy-five percent of all bullying in the workplace is estimated to take the form of downward hostility (Tepper, 2007). In a survey of shop-floor workers at the General Motors and BMW/Rover car plants in the UK, 14 % of respondents stated that they felt they had been bullied by a team leader and 29 % reported that they had been abused by a manager (Stewart et al., 2009). It appears that abusive supervision, or rather subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors excluding physical contact (Tepper, 2000), has become a common form of bullying in organizations. Research has consistently shown the dysfunctional consequences of abusive supervision on subordinates’ work- and family-related outcomes, including unfavorable work attitudes (Tepper, 2000), supervisor-directed deviance (Liu, Kwong Kwan, Wu, & Wu, 2010), work-family conflict (Carlson, Ferguson, Perrewe, & Whitten, 2011), and lower in-role job performance and organizational citizenship behavior (Harris, Kacmar, & Zivnuska, 2007; Zellars, Tepper, & Duffy, 2002). Therefore, understanding the negative impacts of abusive supervision, as well as the underlying mechanisms, is of interest and importance to both scholars and practitioners.

The existing literature has drawn on justice, stress, social exchange, and social learning perspectives to examine the theoretical foundation of how abusive supervision leads to undesirable outcomes (Ng, Chen, & Aryee, 2012). For example, studies have shown that subordinates’ justice perceptions explained their reactions (e.g., lower job satisfaction and affective commitment) to abusive supervision (Tepper, 2000; Zellars et al., 2002). The study of Aryee, Sun, Chen, and Debrah (2008) regarded abusive supervision as a form of workplace stressor and found that it enhanced emotional exhaustion, which in turn undermined subordinates’ contextual performance. Other studies have utilized the social exchange perspective, such as leader-member exchange and trust in supervisor, to determine why abusive supervision leads to increased workplace deviance and decreased organizational citizenship behavior (Tepper, Henle, Lambert, Giacalone, & Duffy, 2008; Xu, Huang, Lam, & Miao, 2012). Lian, Ferris, and Brown (2012) relied on a social learning perspective (i.e., the likelihood of rewards for abusive behaviors) to examine the relationship between abusive supervision and subordinate interpersonal deviance.

Unfortunately, utilizing the four perspectives discussed above has told us little about how subordinates identify or locate themselves within the organization when experiencing abusive supervision. Studies have demonstrated that supervisors’ positive behaviors enhance subordinates’ feeling of belongingness and identification with the organization (Epitropaki & Martin, 2005; Shamir, House, & Arthur, 1993). Since “bad” behaviors often have a stronger and more enduring impact on individuals than “good” ones (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001), we believe that the failure to investigate the consequences of abusive supervision based on a social identity perspective (Tajfel & Turner, 1985) is a significant omission. After being abused by their supervisors, do subordinates go through a psychological identification process to pinpoint their status in the organization, which in turn affects work outcomes? This is one of the main questions of the current study. Further, the existing three studies examining the relationship between abusive supervision and proactive behavior considered voice behavior to be representative of proactivity, which may limit our understanding of how supervisors’ abusive behaviors affect other forms of employee proactive behavior (Frazier & Bowler, 2012; Li, Ling, & Liu, 2010; Rafferty & Restubog, 2011).

While abusive supervision is a common organizational phenomenon as noted above, proactive behavior in the workplace is becoming increasingly desirable because of the complex and fast-changing nature of today’s working environments (Belschak, Den Hartog, & Fay, 2010). Employees’ identification with the organization may provide a new angle to understand the psychological mechanism of how abusive supervision associates with proactive behavior, which would extend our knowledge of the impacts of abusive supervision on subordinates. Thus, it is important to investigate the relationship between abusive supervision and proactive behavior based on a social identity perspective.

To address these important issues in the literature, we draw upon social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1985) to argue that abusive supervision weakens subordinates’ perceived insider status within the organization and causes them to perform proactive behaviors less frequently. We include three types of proactive behavior (i.e., problem prevention, taking charge, and voice) to validate the findings. We also examine whether subordinate gender moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and proactive behavior. According to social role theory (Eagly, 1987; Eagly & Wood, 1999), men and women develop different behavioral patterns as a consequence of social structural impacts, and thus appear to confront deviant or destructive behaviors in different ways (Maki, Moore, Grunberg, & Greenberg, 2005; Mottazl, 1986). We hence propose that the relationship between abusive supervision and proactive behavior varies according to subordinate gender.

This study contributes to our understanding of the relationship between abusive supervision and proactive behavior by capturing subordinates’ identification with the organization (i.e., perceived insider status), which enriches the psychological processes through which abusive supervision operates in the organizational context. It also contributes to the literature by considering how subordinate gender interacts with abusive supervision to influence proactive behavior, thus advancing our knowledge of how male and female subordinates react differently to this type of supervisor mistreatment. Practically, managers are aware of the important role of employees’ sense of belonging to the organization at work and how male and female subordinates react differently to supervisors’ abusive behaviors, thereby performing better on how to attenuate the influence of abusive supervision, improve employees’ perceived insider status, and encourage their proactive behavior.

Theory and hypotheses

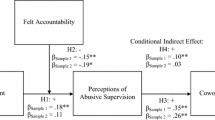

Abusive supervision, a dark side of leadership, has become a widespread phenomenon in organizations. Subordinates are aware of this type of negative leadership behavior and they react accordingly; they experience higher strain, decreased job performance, and increased intention to quit (Huo, Lam, & Chen, 2012; Tepper, 2000). But exactly how this type of leadership affects subordinates’ proactivity, which is particularly desirable in today’s challenging work environment (Belschak et al., 2010), is still unknown and deserves further investigation. Building on a new perspective, namely social identity theory, we propose that a leader’s abusive supervision may directly affect a subordinate’s perceived insider status within the organization and in turn reduce the frequency of proactive behavior. In addition, we examine the role of subordinate gender in this relationship. Figure 1 depicts the theoretical framework of this study.

Abusive supervision and perceived insider status

Perceived insider status refers to the extent to which subordinates feel like organizational insiders rather than outsiders, and represents the close relationship between the subordinate and the organization (Stamper & Masterson, 2002). The perception that some subordinates are of higher value to the organization (insiders) while others are somewhat interchangeable (outsiders) emerges because of the distinct ways in which different workers are treated (Armstrong-Stassen & Schlosser, 2011). Even when performing the same job, subordinates can perceive themselves as having in- or out-group status within the organization through their personal experiences. Employees with high perceived insider status classify themselves as organizational insider members, identify with the organization, feel a sense of belonging to it, and share in its successes and failures (Masterson & Stamper, 2003).

The literature looking at the influences of leadership on how subordinates define and classify themselves mainly focuses on transformational and charismatic leadership, and demonstrates significant positive relationships between these two approaches and subordinates’ identification with the organization (e.g., Epitropaki & Martin, 2005; Shamir et al., 1993; Van Knippenberg, Van Knippenberg, De Cremer, & Hogg, 2004). These studies claim that transformational and charismatic leadership encourages subordinates to associate their self-concept with the organizational mission, which enhances their feelings of involvement and belongingness. This indicates that subordinates perceive immediate supervisors as reliable and qualified agents of the organization (Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski, & Rhoades, 2002). Furthermore, supervisors’ proximity to, and regular interaction with, subordinates means that they have more opportunities to influence the latter’s behavior (Becker, Billings, Eveleth, & Gilbert, 1996). It has also been suggested that subordinates retrieve information from the people close to them (such as their supervisors) to form their attitudes towards the organization (Eisenberger, Karagonlar, Stinglhamber, Neves, Becker, Gonzalez-Morales, and Steiger-Mueller 2010). The relationship with their supervisor is fundamental to subordinates’ definition of themselves at work, and it has been shown that this relationship spills over and affects subordinates’ identification with the organization (Sluss, Ployhart, Cobb, & Ashforth, 2012). We argue, therefore, that the behaviors of immediate supervisors directly affect subordinates’ perceived insider status.

According to social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1985), when supervisors interact with subordinates in a supportive and respectful way and engage in various inclusive behaviors, subordinates are likely to identify with their work role, feel proud to work for the organization, and regard themselves as psychologically involved with the fate of the organization, thereby enhancing their perception of insider status (e.g., Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Kark, Shamir, & Chen, 2003). In contrast, when subordinates are treated in a rude, hostile, or disrespectful way by their supervisors, their need for esteem as individuals cannot be fulfilled, which makes them less willing to dedicate themselves to their work and reduces their sense of belonging to the organization (e.g., Amabile, Schatzel, Moneta, & Kramer, 2004; Schyns & Schilling, 2013). That is to say, such subordinates tend to experience low perceived insider status and view themselves as outsiders within the organization, since they perceive themselves to be excluded by their supervisors and the organization.

However, little research so far has examined the role of abusive supervision on employees’ perceived insider status. The term abusive supervision represents the image of a tyrannical leader who ridicules and undermines his/her subordinates publicly and shows them no respect (Ashforth, 1994). It is a form of downward mistreatment by an immediate supervisor and includes both verbal and nonverbal abuse. It may take the form of criticizing subordinates in front of other colleagues to hurt their feelings, intimidating them through the use of threats such as job loss, and speaking rudely to them in order to elicit the desired task performance (Tepper, 2000). Based on the arguments discussed above, these behaviors indicate to the subordinates on the receiving end that they are not respected or valued by their supervisors. This goes against the notion that work should at least enable one to establish a sense of self-worth and self-respect. As supervisors act as the agents of their organization, these perceptions of disrespect and contempt could be generalized to the organizational level (Sluss & Ashforth, 2007). In other words, even though such abusive behaviors may represent nothing more than supervisors’ personal conduct, subordinates may consider them to reflect an organizational orientation. Accordingly, subordinates regard abusive supervision as an indication that they are being badly treated by the organization and that their work makes little contribution, which in turn weakens their self-perception as an organizational insider. Therefore, abusive supervision tends to reduce subordinates’ perceived insider status within the organization.

Hypothesis 1

Abusive supervision is negatively related to subordinates’ perceived insider status.

The moderating role of subordinate gender

According to Ng et al.’s (2012) review paper on abusive supervision, researchers have investigated various boundary conditions of abusive supervision and related consequences, including individual difference moderators (such as job mobility, reasons for working, and cultural orientations) and contextual factors (such as work unit structure, team member support, and uncertain management style). None of these studies has investigated the potential moderating effect of gender on the relationship between abusive supervision and related consequences, regarding it instead as a control variable only. Drawing upon social role theory (e.g., Eagly, 1987, 1997), we propose that subordinate gender may be a significant moderator of how abusive supervision affects subordinates’ perceived insider status. We focus on subordinate gender in the present study, since research has shown that there is a small gender difference in the typical managerial behaviors of men and women who occupy leadership roles and that supervisors’ gender does not significantly affect how they treat subordinates (Collins, Burrus, & Meyer, 2014; Eagly, Johannesen-Schmidt, & Van Engen, 2003; Hesselbart, 1977).

Social role theory holds that the origin of gender differences in human behavior mainly lies in social structure, suggesting that because men and women tend to occupy different social roles, they are psychologically different in ways that enable them to adjust to these roles (Eagly, 1987; Eagly & Wood, 1999). Different role assignments foster dissimilar expectations for men and women, which are socially modeled, learned, and reinforced through society’s power and status structures. These expectations therefore come to be regarded as normative behavioral guidelines for men and women. For example, the societal expectation of women is that they should be other-oriented and compassionate (Kacmar, Bachrach, Harris, & Zivnuska, 2011; Wood & Eagly, 2002). In addition, gender difference is also a consequence of the acquisition by men and women of different skills and beliefs. For example, men are more likely to adopt aggressive behavior and to hold beliefs that are supportive of such a style (Eagly, 1997). Through these processes, the female gender role promotes a communal and the male an agentic behavior pattern (Eagly, 1987).

In communal patterns, women define themselves through interdependency and good relations with others, whereas men tend to define themselves through independent and personal accomplishments through agentic patterns (Cook, 1993; Nelson & Brown, 2012). When applied to work, this means that male employees are more inclined to place a higher value on extrinsic rewards in the workplace, such as pay and promotion, while social rewards, such as acceptance and good relations with supervisors and coworkers, are considered more salient for female employees (Helgesen, 2003; Mottazl, 1986). In summary, women are more empathic and relationship-oriented and emphasize interaction and social support. In contrast, men are more competitive and task-oriented and focus on autonomy and personal success.

Men and women may also respond differently when experiencing stress and difficult behaviors. It is suggested that the two genders display two distinct stress orientations. Females view relationship stress as a negative event and take responsibility for others, whereas males are capable of detaching themselves from relational issues and focusing on themselves (Iwasaki, MacKay, & Ristock, 2004; Maki et al., 2005). Also, women resist becoming involved in conversations that may prove to be aggressive (Koonce, 1997). Nelson and Brown (2012) elucidated the relationship between gender difference and conflict styles. To put it simply, men are more combative and challenging; women tend to be more cooperative and agreeable, to avoid confrontation, and take care of others. Therefore, when experiencing negative behaviors related to interpersonal relationships, women appear to be more sensitive to, and influenced by, these events than men.

Based on the above, subordinate gender could be an important moderator of the relationship between abusive supervision and subordinates’ perceived insider status. A friendly and supportive relationship with supervisors has been shown to be more important for female subordinates than it is for male subordinates (Mottazl, 1986). When treated abusively by a supervisor, female subordinates seem to respond more strongly and to be more likely to perceive themselves as outsiders in the group or organization. We therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

Subordinate gender moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and subordinates’ perceived insider status, such that the negative relationship is stronger for female subordinates than for male subordinates.

Perceived insider status and proactive behavior

Proactive behavior relies on individual initiative and self-starting, which indicates that it requires a high level of motivation (Parker, Bindl, & Strauss, 2010). We propose that perceived insider status may act as a crucial impetus for proactivity in the workplace. Perceived insider status involves an individual’s feelings of emotional attachment or connection to the organization. Subordinates’ experience of perceived insider status has been demonstrated to be positively related to organizational citizenship behavior, and negatively associated with turnover and deviant behavior (Masterson & Stamper, 2003; Stamper & Masterson, 2002). Subordinates with high perceived insider status define themselves as members of the organization, agree with its values and goals, and act in the ways it expects of them; their intention to remain in the organization is high. On the contrary, if perceived insider status is low (that is, individuals perceive themselves as being outsiders in the organization), they possess feelings of detachment and rejection rather than pride and high involvement (Armstrong-Stassen & Schlosser, 2011; Stamper & Masterson, 2002).

We argue that high perceived insider status may motivate subordinates to perform proactive behavior, through two mechanisms. On the one hand, it may trigger subordinates’ positive affect and then encourage them to use their initiative to challenge the status quo and make changes. This mechanism corresponds to Parker et al.’s (2010) concept “energized to motivation,” which asserts that affect-related motivational states can influence proactive behavior. According to the literature, positive affect promotes a more responsible long-term perspective and innovative behaviors, stimulates individuals to set challenging goals, and encourages engagement in proactive behaviors (Ilies & Judge, 2005; Isen & Reeve, 2005; Parker et al., 2010). On the other hand, perceived insider status also represents a sense of psychological attachment to the organization, which indicates that the individual cares about the interests of the organization, has a willingness to get involved, and strives to achieve its goals (Johnson & Yang, 2010). This mechanism is consistent with Parker et al.’s (2010) “reason to motivation” concept, which suggests that individuals act proactively in order to fulfill important goals and feel a sense of personal accomplishment. Therefore, subordinates with high perceived insider status are more likely to be stimulated to behave proactively to explore how to contribute to the organization.

In the current study, we focus on three specific proactive behaviors: problem prevention, taking charge, and voice behavior. Problem prevention refers to self-directed and anticipatory action to prevent the reoccurrence of work difficulties (Frese & Fay, 2001); taking charge involves exercising initiative to improve work structures, practices, and routines (Morrison & Phelps, 1999); and voice behavior refers to making innovative suggestions for change and recommending modifications to standard procedures (Van Dyne & Lepine, 1998). The reason we selected these three types of proactive behavior is that all three belong to a category of proactive work behavior which emphasizes taking control of, and bringing about change within, the internal organizational environment (Parker & Collins, 2010), and are thus aligned with the focus on perceived insider status (that is, the organization itself) in this study. We further hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

Subordinates’ perceived insider status is positively related to their proactive behavior, such as (a) problem prevention, (b) taking charge, and (c) voice behavior.

The mediating role of perceived insider status

Social identity theory highlights how individuals define and position themselves within the organizational context (e.g., Ashforth & Mael, 1996; Hogg & Terry, 2001). It suggests that leader behaviors could provide subtle clues and critical information to subordinates, which affect their self-concept based on organizational identity; meanwhile, the perception of being an organizational insider or outsider determines the extent to which individuals engage with their work and make efforts to achieve organizational goals (Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Shamir, Zakay, Brainin, & Popper, 2000). A social identity perspective is thus an appropriate approach to investigate how leader behaviors associate with employees’ work outcomes. Prior research has utilized this perspective to examine the impacts of leaders’ positive behaviors (e.g., emphasis on shared values and inclusive behaviors) on subordinates, such as self-efficacy and organization-based self-esteem (Kark et al., 2003; Shamir et al., 2000). Based on the above discussion, we speculate that perception of organizational insider status is shaped between the experience of abusive supervision and subordinates’ behavioral reactions. Given that we have hypothesized the effect of abusive supervision on perceived insider status (Hypothesis 1) and the relationship between perceived insider status and proactive behavior (Hypothesis 3), we expect that perceived insider status carries the effect of abusive supervision to subordinate proactive behavior. We therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4

Subordinates’ perceived insider status mediates the relationship between abusive supervision and proactive behavior, such as (a) problem prevention, (b) taking charge, and (c) voice behavior.

Methods

Sample and procedure

The data were collected from four telecommunication equipment manufacturing companies within an IT group corporation located in Shanghai, China. As abusive supervision is a relatively sensitive issue, with the support of the human resource departments of these companies we arranged a joint 2-day recreational trip for staff of all four units in order to collect high-quality and -quantity data. In conducting the survey during activities external to the workplace, a better response rate was achieved.

During the trip, we approached all of the subordinates and their supervisors in person and gave them a briefing about the objectives of the study and how to complete the questionnaire. Each respondent also received a cover letter about the study’s purpose, an informed consent form to sign and thus confirm his/her voluntary participation, a questionnaire, and a return envelope. In order to encourage greater honesty from the participants, they were allowed to respond anonymously. In addition, to preserve the confidentiality of the data, respondents were asked to seal the finished questionnaires in the prepared envelope and return them directly to the researchers. The questionnaires were coded before distribution and the human resource departments assisted us in recording identity numbers and the respondents’ names to match supervisor–subordinate dyads. On average, each supervisor rated four subordinates.

Five hundred and six supervisor–subordinate dyads were invited to participate in the survey. The questionnaires of 350 dyads were usable, yielding a response rate of 69.2 %. Table 1 presents detailed statistical information about the sample.

Measures

The survey instrument was administered in Chinese. Since the original scales used were developed in English, all of the items underwent a back-translation process (Brislin, 1986). The items were first translated into Chinese by one bilingual scholar and then translated back into English by another, thus ensuring a high degree of clarity and accuracy.

The constructs of abusive supervision and perceived insider status were rated by the subordinates, and the frequency of proactive behavior (problem prevention, taking charge, and voice behavior) by their immediate supervisors. All measures were rated on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree), except for the measure of abusive supervision, which was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = never; 5 = very often).

Abusive supervision

We used the 15-item abusive supervision scale developed by Tepper (2000). Respondents rated the frequency with which their supervisors engaged in the behavior described in each of the 15 items, sample items being “Puts me down in front of others” and “Tells me I am incompetent.” The Cronbach α for this scale was .97.

Perceived insider status

We employed the 6-item perceived insider status scale developed by Stamper and Masterson (2002). Sample items include “I feel very much a part of my work organization” and “My work organization makes me frequently feel ‘left-out’” (reverse-coded item). The Cronbach α for this scale was .81.

Proactive behavior

To assess the three types of proactive behavior, we used three 3-item scales developed by Parker and Collins (2010). A sample item for problem prevention is “This subordinate tries to find the root cause of things that go wrong”; the Cronbach α for this scale was .86. A sample item for taking charge is “This subordinate tries to institute new work methods that are more effective”; the Cronbach α for this scale was .94. A sample item for voice is “This subordinate speaks up and encourages others in the workplace to get involved with issues that affect us”; the Cronbach α for this scale was .87.

Subordinate gender

A dummy variable (female = 1, male = 0) was created to represent subordinate gender.

Control variables

We controlled for subordinate age, education, and organizational tenure in our data analyses since previous research has found such demographic variables to influence individual proactive behavior (for a review see Bindl & Parker, 2010). In addition, we controlled for supervisor gender to rule out any possible influence of supervisor gender or the gender composition of the supervisor–subordinate dyad on how subordinates react to their supervisors’ abusive behaviors (Douglas, 2012).

Analytical strategy

As we aimed to test the mediating role of perceived insider status in the relationship between abusive supervision and three forms of proactive behavior and the moderating effect of subordinate gender on abusive supervision-perceived insider status linkage, we needed to choose an appropriate analytical tool capable not only of considering both mediation and moderation but also estimating multiple dependent variables in a model simultaneously. In recent years, Mplus has been regarded as such a tool, enabling researchers to examine SEM models that contain both moderation and mediation. Therefore, our data analysis consisted of two parts: (1) conducting confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine the discriminant validity of the constructs; (2) using Mplus to test the research hypotheses.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Discriminant validity

Before testing the hypotheses, we conducted a series of CFAs to obtain statistical support for the discriminant validity using AMOS 19.0. First, we tested both two- and single-factor models to evaluate the discrimination between abusive supervision and perceived insider status as rated by subordinates. The results suggested that the two-factor model (CFI = .96, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .06) yielded a better fit than the single-factor model (CFI = .87, TLI = .84, RMSEA = .12), with a change in chi-square of 512.79 (∆df = 1, p < .001). Second, we conducted another CFA to examine whether the three types of proactive behavior rated by supervisors were distinguishable. The results revealed that the three-factor model (CFI = .97, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .09) yielded a better fit than the single-factor model (CFI = .74, TLI = .61, RMSEA = .28), with a change in chi-square of 607.62 (∆df = 3, p < .001).

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and zero-order Pearson correlations of all the key and control variables, providing a basis for testing the hypotheses.

Hypotheses testing

As we collected data from four companies within a group corporation and each supervisor had rated more than one subordinate in our sample, we were concerned about clustering issues. Before conducting SEM, we therefore calculated the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) to examine the differences among the four companies and the group variances of the supervisor-rating variables, and we also computed design effects using the formula suggested by Hox and Maas (2002). Design effect indicates how much the standard errors are underestimated in a complex sample compared to a simple random sample (Kish, 1965). Scholars suggest that if the design effect in cluster samples is smaller than 2, single level analysis would not lead to misleading results (Satorra & Muthen, 1995). The results are shown in Table 3. All of the ICCs were in the range of .05–.09, and the design effects were below 2, indicating that there was no significant difference among the four companies and the group variances were small. Therefore, it was reasonable to analyze the data at the individual level (Hox, 2002; Hox & Maas, 2002). We then used Mplus 6.0 to conduct the SEM and tested the entire model, including all direct and indirect path coefficients (standardized βs). The results of the analyses are presented in Fig. 2. The model fit was reasonably good (χ 2 = 1768.52, df = 586; CFI = .91, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .07). We also examined the model without the mediator of perceived insider status (χ 2 = 1482.90, df = 401; CFI = .87, TLI = .86, RMSEA = .09), which indicates that the proposed model yields a better fit.

As shown in Fig. 2, abusive supervision was negatively associated with subordinates’ perceived insider status (β = −.29, p < .001), thus supporting Hypothesis 1. The abusive supervision–subordinate gender interaction was negatively related to subordinates’ perceived insider status (β = −.39, p < .001). To facilitate the interpretation of the moderating effect, we plotted simple slopes for the relationship between abusive supervision and perceived insider status for male and female subordinates. Figure 3 illustrates the pattern of how abusive supervision and subordinate gender jointly influence subordinates’ perceived insider status. As expected, simple slope tests revealed that abusive supervision had a stronger negative effect on subordinates’ perceived insider status when subordinates were female (b = −.41, p < .001) than they were male (b = −.02, n.s.). Hypothesis 2 is supported.

Figure 2 also show that subordinates’ perceived insider status was positively related to their proactive behavior in the workplace, that is, problem prevention (β = .19, p < .01), taking charge (β = .10, p < .10), and voice behavior (β = .15, p < .05), supporting Hypothesis 3. Hypothesis 4 predicts the mediating effect of perceived insider status on the abusive supervision-proactive behavior relationship. Combined with the hypothesis of the moderating effect of subordinate gender (H2), we need to test whether the indirect effect of abusive supervision on proactive behavior via perceived insider status varied between male and female subordinates. We obtained these indirect effects by using bootstrap approximation in Mplus (see Table 4). We found that the direct effects of abusive supervision on problem prevention (β = −.23, p < .01), taking charge (β = −.16, p < .05), and voice (β = −.21, p < .01) were all negative and significant. Similarly, for female subordinates, the indirect effects of abusive supervision through perceived insider status on problem prevention (β = −.13, p < .01), taking charge (β = −.07, p < .10), and voice (β = −.10, p < .05) were all negative and significant; they were all insignificant for male subordinates (β = −.06, −.03, and −.05, n.s.). These results suggest that perceived insider status partially mediated the interaction of abusive supervision and subordinate gender on subordinate proactive behavior, which partially supports Hypothesis 4.

Discussion

In the existing research on abusive supervision, researchers have explored and examined several categories of relevant outcomes (such as subordinate well-being and work behavior) mainly on the basis of four perspectives (justice, stress, social exchange, and social learning) (Lian et al., 2012; Ng et al., 2012). This study set out to extend this strand of research by employing social identity theory to investigate how abusive supervision affects subordinates’ proactive behavior in the workplace. Another major aim is to explore the different reactions of female and male subordinates to abusive supervision or, in other words, to explore the moderating effect of gender on the abusive supervision-proactive behavior relationship. By building social role theory into the social identity framework, our research provides general support for the proposition that subordinates’ perceived insider status partially mediates the negative relationship between abusive supervision and proactive behavior (Hypotheses 1, 3, and 4), and that the subordinate’s gender moderates the abusive supervision-perceived insider status relationship (Hypothesis 2). Specifically, the relationship is significantly negative for female subordinates; in contrast, it is nonsignificant for male subordinates. Below, we discuss the theoretical and practical contributions of our study as well as its limitations.

Theoretical contributions

This study makes three main theoretical contributions. First, we introduce social identity theory as a means to interpret the linkage between abusive supervision and subordinates’ proactive behavior, and test that framework empirically. Social identity theory is frequently invoked in organizational research (e.g., Mcdonald & Westphal, 2011; Sluss et al., 2012), and our research extends this theory to the field of abusive supervision. As noted earlier, the theoretical foundation of abusive supervision and its consequences is usually based on the justice, stress, social exchange, or social learning perspective (Lian et al., 2012; Ng et al., 2012). However, we predicted that abusive supervision could directly affect subordinates’ perception of their insider status within the organization and hence have an impact upon their proactive behavior. The results support our prediction, indicating that in subordinates’ view, supervisors’ abusive behaviors are considered to represent not only themselves as individuals but also the organization, and will prompt feelings of being disrespected and treated with contempt among subordinates. Consequently, subordinates’ identification with the organization is reduced, which results in reduced levels of proactive behavior. Specifically, we reconfirm previous findings that supervisors act as agents of the organization and their interactions with subordinates provide the latter with crucial information (Becker et al., 1996; Eisenberger et al., 2002). Our results further suggest that subordinates’ perception of insider status partially mediates the relationship between abusive supervision and their proactive behavior in the workplace. This implies that abusive supervision is seen to represent the way an organization treats its employees, who correspondingly adjust their identities within the organization (that is, their perceived insider status is reduced). Accordingly, employees’ initiative and proactivity are frustrated. Therefore, social identity theory is validated as an explanation of the underlying psychological mechanism governing the abusive supervision-proactive behavior relationship.

Second, our research contributes to the literature on abusive supervision and proactive behavior. A few recent studies have examined this relationship in terms of voice (a type of proactive behavior) (Frazier & Bowler, 2012; Li et al., 2010; Rafferty & Restubog, 2011). In embarking on this research, we wondered whether these findings could be generalized to other forms of proactive behavior. We thus selected three types (problem prevention, taking charge, and voice behavior) in order to examine the extent to which it is possible to generalize about how proactive behaviors are affected by abusive supervision. In addition, the research on how leadership influences proactivity always focuses on the “bright side” of supervisors’ behavior (Parker et al., 2010; Strauss, Griffin, & Rafferty, 2009). We have explored the dark side, which may be equally crucial in obtaining an integrated understanding of effective leadership in organizations. Our findings reveal the destructive effect of abusive supervision on subordinates’ proactive behavior. To be more specific, we have found that abusive supervision is negatively associated with the frequency of all three types of proactive behavior through subordinates’ perceived insider status. That is to say, perceived insider status acts as a mediator between abusive supervision and proactive behavior.

Third, this study has integrated social role theory into a social identity theory framework, and as a result has identified implications for how subordinate gender differentiates the relationship between abusive supervision and perceived insider status. As noted earlier, researchers have previously examined various boundary conditions (such as job mobility, cultural orientation, and team member support) of abusive supervision and relevant outcomes (Ng et al., 2012). However, little previous study has explored the moderating effect of gender, though many researchers have incorporated it as a control variable. Based on social role theory, we predicted that gender could be an important boundary condition for this relationship because females and males tend to have different behavior patterns and to respond dissimilarly when encountering stress and negative behaviors (Eagly, 1997; Maki et al., 2005). Our findings indicate that the effect of abusive supervision on subordinates’ perceived insider status is not uniform, which supports our argument; rather, supervisors’ abusive behaviors interact with subordinate’s gender to guide the latter’s evaluations of supervisory behavior, which in turn has an impact on their identification with the organization. Specifically, the negative abusive supervision-perceived insider status relationship is much stronger for female than male subordinates. This conclusion is noteworthy given that the specific role of gender has not previously been explored in research on abusive supervision, and it provides us with valuable insight into how to alleviate its negative effects and boost subordinates’ proactive behavior.

Practical implications

From a practical perspective, there are two key implications for supervisors and organizations. First, our findings suggest that abusive supervision could negatively affect subordinates’ perception of organizational insider status, thus reducing their motivation to take the initiative and behave proactively. Previous research has revealed that employees’ identification with their organization has significant impacts on the maintenance of high individual job performance and organizational effectiveness (e.g., Dutton, Dukerich, & Harquail, 1994; Zhang & Chen, 2013). Our study further highlights the importance of employees’ insider feelings within the organization. Since perceived insider status underlies the linkage between abusive supervision and employee proactive behavior, improving employees’ perception of themselves as insiders of the organization could be a reasonable approach to offset the detrimental effect of abusive supervision and strengthen individual proactivity. Therefore, organizations should utilize various inducements, such as delegation, promotion, and training, to develop high-quality employee-organization relationships and send signals to employees that they are regarded as organizational insiders.

Second, our findings indicate that female and male subordinates respond differently to abusive supervision. A female subordinate is more sensitive to her supervisor’s abusive behaviors, and her perceived insider status decreases significantly. The same effect takes place for male subordinates but the effect is not significant. This implies that organizations could tailor their interventions to alleviate the negative impacts of abusive supervision according to the gender of subordinates. Counseling services and support or assistance programs aimed specifically at female subordinates might be helpful to mitigate the destructive effect of abusive supervision and help them to maintain their perceived insider status, thereby minimizing the decline of proactive behavior.

Limitations and future research

Despite these contributions, several limitations should be noted. The first of these is that the cross-sectional design of our study hinders the formulation of firm conclusions on the causal direction for the paths tested in our model. Individuals may attribute their decreased level of proactive behavior to supervisors’ abusive behaviors. Therefore, a longitudinal research design is required to provide stable evidence of causality (Fedor, Rensvold, & Adam, 1992).

Second, we cannot be sure that our findings are representative of other types of organizations or cultural settings, since the data for the current study were collected from a single IT corporation in one city of mainland China (namely Shanghai). In other words, the nature of our sample may evoke questions about generalizability. However, Shanghai is becoming an international metropolis and is seen as the economic and cultural center of East Asia (Schlevogt, 2001). Thus, the model developed here in the context of Shanghai may be generalizable to other international cultures. Even so, we recommend that further research examine our proposed relationships across various organizations and cultural contexts to test their generalizability and to explain any differences that may emerge.

Another limitation is the operationalization of abusive supervision. As in previous studies, we adopted a self-report approach to measure the construct. However, subordinates’ perceptions may be underreported or exaggerated, which makes it difficult to confirm the actual level of abusive supervision taking place (Ng et al., 2012; Tepper, Duffy, Henle, & Lambert, 2006). As described in the Method section, we arranged a 2-day recreational trip for subordinates and assured respondents’ anonymity and the confidentiality of all data. These procedures were applied to minimize the potential risk of an inaccurate measure of abusive supervision. Future research could collect data from different sources (such as supervisor self-reports, coworker reports, and archives) as a check on objectivity and accuracy.

A final limitation is that we only examined one moderator (that is, subordinate gender) of the abusive supervision-proactive behavior relationship. The results indicate that female subordinates react more strongly to abusive supervision than males, present a lower level of identification with their organizations, and hence engage in less proactive behavior. Our study has therefore uncovered a significant boundary condition for the relationship between abusive supervision and proactive behavior. However, Ng et al. (2012) showed that subordinates’ personal characteristics (such as conscientiousness and agreeableness) and situational factors (such as coworker support and work unit structure) moderate the relationship between abusive supervision and work outcomes. The authors propose introducing cultural orientation as a possible moderator. Therefore, a potential avenue for future research would be to explore other boundary conditions of the model proposed here.

Conclusion

Our research provides the first test of the use of social identity theory to interpret the abusive supervision-proactive behavior relationship and also integrates social role theory to examine the moderating effect of subordinate gender. Our findings indicate that subordinates’ perceived insider status partially mediates the relationship between abusive supervision and proactive behavior, and that gender moderates the link between abusive supervision and perceived insider status. Female subordinates react more strongly to abusive supervision, which significantly decreases their perceived insider status and results in less proactive behavior. We also provide insights for managers into how to alleviate the harmful effects of abusive supervision. In conclusion, our research sheds light on the timely issue of abusive supervision and proactive behavior in the workplace.

References

Amabile, T. M., Schatzel, E. A., Moneta, G. B., & Kramer, S. J. 2004. Leader behaviors and the work environment for creativity: Perceived leader support. Leadership Quarterly, 15(1): 5–32.

Armstrong-Stassen, M., & Schlosser, F. 2011. Perceived organizational membership and the retention of older workers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(2): 319–344.

Aryee, S., Sun, L.-Y., Chen, Z. X. G., & Debrah, Y. A. 2008. Abusive supervision and contextual performance: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion and the moderating role of work unit structure. Management and Organization Review, 4(3): 393–411.

Ashforth, B. 1994. Petty tyranny in organizations. Human Relations, 47(7): 755–778.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. 1989. Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1): 20–39.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. A. 1996. Organizational identity and strategy as a context for the individual. Advances in Strategic Management, 13: 19–64.

Avolio, B. J., & Gardner, W. L. 2005. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 16(3): 315–338.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. 2001. Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4): 323–370.

Becker, T. E., Billings, R. S., Eveleth, D. M., & Gilbert, N. L. 1996. Foci and bases of employee commitment: Implications for job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39(2): 464–482.

Belschak, F. D., Den Hartog, D. N., & Fay, D. 2010. Exploring positive, negative and context-dependent aspects of proactive behaviours at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(2): 267–273.

Bindl, U. K., & Parker, S. K. 2010. Proactive work behavior: Forward-thinking and change-oriented action in organizations. In S. Zedeck (Ed.). APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, 2nd ed.: 567–598. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Brislin, R. W. 1986. The wording and translation of research instrument. In J. W. B. W. J. Lonner (Ed.). Field methods in cross-cultural research: 137–164. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Carlson, D. S., Ferguson, M., Perrewe, P. L., & Whitten, D. 2011. The fallout from abusive supervision: An examination of subordinates and their partners. Personnel Psychology, 64: 937–961.

Collins, B. J., Burrus, C. J., & Meyer, R. D. 2014. Gender differences in the impact of leadership styles on subordinate embeddedness and job satisfaction. Leadership Quarterly. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.02.003.

Cook, E. P. 1993. The gendered context of life: Implications for women’s and men’s career-life plans. Career Development Quarterly, 41(3): 227–237.

Douglas, C. 2012. The moderating role of leader and follower sex in dyads on the leadership behavior–leader effectiveness relationships. Leadership Quarterly, 23(1): 163–175.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. 1994. Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2): 239–263.

Eagly, A. H. 1987. Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Eagly, A. H. 1997. Sex differences in social behavior: Comparing social role theory and evolutionary psychology. American Psychologist: 1380–1383.

Eagly, A. H., Johannesen-Schmidt, M. C., & Van Engen, M. L. 2003. Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: A meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychological Bulletin, 129(4): 569–591.

Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. 1999. The origins of sex differences in human behavior: Evolved dispositions versus social roles. American Psychologist, 54(6): 408–423.

Eisenberger, R., Karagonlar, G., Stinglhamber, F., Neves, P., Becker, T. E., Gonzalez-Morales, M. G., & Steiger-Mueller, M. 2010. Leader-member exchange and affective organizational commitment: The contribution of supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(6): 1085–1103.

Eisenberger, R., Stinglhamber, F., Vandenberghe, C., Sucharski, I. L., & Rhoades, L. 2002. Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3): 565–573.

Epitropaki, O. & Martin, R. 2005. The moderating role of individual differences in the relation between transformational/transactional leadership perceptions and organizational identification. Leadership Quarterly (16): 569–589.

Fedor, D. B., Rensvold, R. B., & Adam, S. M. 1992. An investigation of factors expected to affect feedback seeking: A longitudinal field study. Personnel Psychology, 45(4): 779–802.

Frazier, M. L. & Bowler, W. M. 2012. Voice climate, supervisor undermining, and work outcomes: A group-level examination. Journal of Management. doi:10.1177/0149206311434533.

Frese, M., & Fay, D. 2001. Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Research in Organizational Behavior, 23: 133–187.

Harris, K. J., Kacmar, K. M., & Zivnuska, S. 2007. An investigation of abusive supervision as a predictor of performance and the meaning of work as a moderator of the relationship. Leadership Quarterly, 18(3): 252–263.

Helgesen, S. 2003. The female advantage. In R. J. Ely, M. A. Scully, & E. G. Foldy (Eds.). Reader in gender, work and organization: 26–33. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hesselbart, S. 1977. Sex role and occupational stereotypes: Three studies of impression formation. Sex Roles, 3(5): 409–422.

Hogg, M. A., & Terry, D. J. 2001. Social identity processes in organizational contexts. Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

Hox, J. J. 2002. Multilevel analysis: Technique and application. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hox, J. J. & Maas, C. J. M. 2002. Sample sizes for multilevel modeling. In J. Blasius, J. Hox, E. de Leeuw, & P. Schmidt (Eds.). Social science methodology in the new millennium: Proceedings of the fifth international conference on logic and methodology (CD-ROM; 2nd ed., expanded) http://www.fss.uu.nl/ms/jh/publist/simnorm1.pdf.

Huo, Y., Lam, W., & Chen, Z. 2012. Am I the only one this supervisor is laughing at? Effects of aggressive humor on employee strain and addictive behaviors. Personnel Psychology, 65(4): 859–885.

Ilies, R., & Judge, T. A. 2005. Goal regulation across time: The effects of feedback and affect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90: 453–467.

Isen, A. M., & Reeve, J. 2005. The influence of positive affect on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: Facilitating enjoyment of play, responsible work behavior, and self-control. Motivation and Emotion, 29: 295–323.

Iwasaki, Y., MacKay, K. J., & Ristock, J. 2004. Gender-based analyses of stress among professional managers: An exploratory qualitative study. International Journal of Stress Management, 11(1): 56–79.

Johnson, R. E., & Yang, L.-Q. 2010. Commitment and motivation at work: The relevance of employee identity and regulatory focus. Academy of Management Review, 35(2): 226–245.

Kacmar, K. M., Bachrach, D. G., Harris, K. J., & Zivnuska, S. 2011. Fostering good citizenship through ethical leadership: Exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3): 633–642.

Kark, R., Shamir, B., & Chen, G. 2003. The two faces of transformational leadership: Empowerment and dependency. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2): 246.

Kish, L. 1965. Survey sampling. New York: Wiley.

Koonce, R. 1997. Language, sex, and power: Women and men in the workplace. Training and Development, 51(9): 34–40.

Li, R., Ling, W.-Q., & Liu, S.-S. 2010. The mechanisms of how abusive supervision impacts on subordinates’ voice behavior. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 41(12): 1189–1202.

Lian, H., Ferris, D. L., & Brown, D. J. 2012. Does power distance exacerbate or mitigate the effects of abusive supervision? It depends on the outcome. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1): 107–123.

Liu, J., Kwong Kwan, H., Wu, L.-Z., & Wu, W. 2010. Abusive supervision and subordinate supervisor-directed deviance: The moderating role of traditional values and the mediating role of revenge cognitions. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4): 835–856.

Maki, N., Moore, S., Grunberg, L., & Greenberg, E. 2005. The responses of male and female managers to workplace stress and downsizing. North American Journal of Psychology, 7(2): 295–312.

Masterson, S. S., & Stamper, C. L. 2003. Perceived organizational membership: An aggregate framework representing the employee-organization relationship. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(5): 473–490.

Mcdonald, M. L., & Westphal, J. D. 2011. My brother’s keeper? CEO identification with the corporate elite, social support among CEOS, and leader effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 54(4): 661–693.

Morrison, E. W., & Phelps, C. C. 1999. Taking charge at work: Extrarole efforts to initiate workplace change. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4): 403–419.

Mottazl, C. 1986. Gender differences in work satisfaction, work-related rewards and values, and the determinants of work satisfaction. Human Relations, 39(4): 359–377.

Nelson, A., & Brown, C. D. 2012. The gender communication handbook: Conquering conversational collisions between men and women. San Francisco: Pfeiffer; Wiley.

Ng, S. B. C., Chen, Z. X., & Aryee, S. 2012. Abusive supervision in Chinese work settings. In X. Huang & M. H. Bond (Eds.). Handbook of Chinese organizational behavior: Integrating theory, research and practice: 164–183. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. 2010. Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4): 827–856.

Parker, S. K., & Collins, C. G. 2010. Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. Journal of Management, 36(3): 633–662.

Rafferty, A. E., & Restubog, S. L. D. 2011. The influence of abusive supervisors on followers’ organizational citizenship behaviours: The hidden costs of abusive supervision. British Journal of Management, 22(2): 270–285.

Satorra, A., & Muthen, B. 1995. Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociological Methodology, 25: 267–316.

Schlevogt, K. A. 2001. Institutional and organizational factors affecting effectiveness: Geoeconomic comparison between Shanghai and Beijing. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 18(4): 519–551.

Schyns, B., & Schilling, J. 2013. How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. Leadership Quarterly, 24(1): 138–158.

Shamir, B., House, R. J., & Arthur, M. B. 1993. The motivational effects of charismatic leadership. Organization Science (4): 577–594.

Shamir, B., Zakay, E., Brainin, E., & Popper, M. 2000. Leadership and social identification in military units: Direct and indirect relationships. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(3): 612–640.

Sluss, D. M., & Ashforth, B. E. 2007. Relational identity and identification: Defining ourselves through work relationships. Academy of Management Review, 32(1): 9–32.

Sluss, D. M., Ployhart, R. E., Cobb, M. G., & Ashforth, B. E. 2012. Generalizing newcomers’ relational and organizational identifications: Processes and prototypicality. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4): 949–975.

Stamper, C. L., & Masterson, S. S. 2002. Insider or outsider? How employee perceptions of insider status affect their work behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(8): 875–894.

Stewart, P., Murphy, K., Danford, A., Richardson, T., Richardson, M., & Wass, V. 2009. We sell our time no more: Workers’ struggles against lean production in the British car industry. London: Pluto Press.

Strauss, K., Griffin, M. A., & Rafferty, A. E. 2009. Proactivity directed toward the team and organization: The role of leadership, commitment and role-breadth self-efficacy. British Journal of Management, 20(3): 279–291.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. 1985. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.). Psychology of intergroup relations, 2nd ed.: 7–24. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Tepper, B. J. 2000. Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2): 178–190.

Tepper, B. J. 2007. Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33(3): 261–289.

Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M., Henle, C., & Lambert, L. S. 2006. Procedural injustice, victim precipitation, and abusive supervision. Personnel Psychology, 59: 101–123.

Tepper, B. J., Henle, C. A., Lambert, L. S., Giacalone, R. A., & Duffy, M. K. 2008. Abusive supervision and subordinates’ organization deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4): 721–732.

Van Dyne, L., & Lepine, J. A. 1998. Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1): 108–119.

Van Knippenberg, D., Van Knippenberg, B., De Cremer, D., & Hogg, M. A. 2004. Leadership, self and identity: A review and research agenda. Leadership Quarterly (15): 825–856.

Wood, W., & Eagly, A. H. 2002. A cross-cultural analysis of the behavior of women and men: Implications for the origins of sex differences. Psychological Bulletin, 128(5): 699–727.

Xu, E., Huang, X., Lam, C. K., & Miao, Q. 2012. Abusive supervision and work behaviors: The mediating role of LMX. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(4): 531–543.

Zellars, K. L., Tepper, B. J., & Duffy, M. K. 2002. Abusive supervision and subordinates’ organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(6): 1068.

Zhang, Y., & Chen, C. C. 2013. Developmental leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: Mediating effects of self-determination, supervisor identification, and organizational identification. Leadership Quarterly, 24(4): 534–543.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Professor Alfred Wong and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive and detailed comments during the revision process. We also appreciate the insightful feedback on previous drafts from Professor Ziguang Chen. This research was supported by grants from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (GRF no. PolyU 5445/12H).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ouyang, K., Lam, W. & Wang, W. Roles of gender and identification on abusive supervision and proactive behavior. Asia Pac J Manag 32, 671–691 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9410-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9410-7