Abstract

This study examines how the host country experience of Japanese multinational corporations (MNCs) affects their staffing policies for executive manager positions at foreign affiliates. Hypotheses on executive staffing policies for foreign affiliates are tested using survey data collected from 103 Japanese affiliates in Korea. Findings show that the level of global integration and the degree of centralization of decision-making positively affect an assignment of parent country nationals as executive managers of foreign affiliates. We further find that foreign affiliates’ experience in a host country moderates the effects of both global integration and centralization on staffing decisions for the affiliates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Staffing policies for foreign affiliates have been identified as one of the significant factors affecting an overall performance of multinational corporations (MNCs) (e.g., Delios & Björkman, 2000; Harvey & Richey, 2001; Peterson, Sargent, Napier, & Shim, 1996; Richards, 2001; Robson, Paparoidamis, & Ginoglu, 2003; Wang, Wee, & Koh, 1998). The dual perspectives of expatriate managers’ assignments, as coordinators and as executors, have escalated the sophistication of expatriate policies to the level that previous research may not provide practical guidance for some MNCs. Thus, in spite of a large number of studies on the topic, the question of whether a specific foreign affiliate of MNCs should be managed by an expatriate from the home country (or parent country nationals, PCNs) or host country nationals (HCNs) may still remain as a critical issue in both academia and business fields.

While most research on staffing policies for foreign affiliates has examined US MNCs (e.g., Downes & Thomas, 2000), a body of research has investigated expatriation decisions of Japanese MNCs (e.g., Baliga & Jaeger, 1984; Beechler & Yang, 1994; Belderbos, 1997; Delios & Björkman, 2000; Jaeger, 1983; Paik & Sohn, 2004; Rodgers & Wong, 1996; Tung, 1984). Compared to the practices of US MNCs, one of the recognizable distinctions for Japanese MNCs is that they often prefer PCNs for executive positions at foreign affiliates to HCNs. For example, Jaeger (1983) suggested that Japanese MNCs make extensive use of PCNs for their overseas affiliates. A recent study among foreign affiliates in Asia reconfirmed that Japanese MNCs’ reliance on PCNs is still continuing and is substantially greater than American and German MNCs (MITI (Ministry of International Trade and Industry), 2000). Early studies on Japanese MNCs attributed such reliance on PCNs to their management practices including lifetime employment systems, extensive job transfer systems, seniority-based compensation and cultural control (Baliga & Jaeger, 1984; Beechler & Yang, 1994; Jaeger, 1983; Tung, 1984). Other studies explained Japanese MNCs’ staffing practice for foreign affiliates by highlighting the need to transfer tacit knowledge and best practices, such as high-tech patents, total quality control system and JIT processes (Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005; Delios & Björkman, 2000; Rodgers & Wong, 1996).

Assuming that the reliance on PCNs is the general trend, however, most of the previous studies on Japanese MNCs’ staffing decisions for foreign affiliates have investigated the question, ‘why do Japanese MNCs rely heavily on PCNs?’ (Bartlett & Yoshihara, 1988; Beamish & Inkpen, 1998; Jaeger & Baliga, 1985; Tung, 1984) They examined various linear relationships between organizational characteristics, corporate culture, compensation, knowledge transfer and learning and the reliance on PCNs. Considering the effort of previous studies, it now seems necessary to investigate a more complex question, ‘under what conditions is it more or less likely that Japanese MNCs rely on PCNs for their staffing at foreign affiliates?’ Possible research on the question may examine interaction effects of various factors on staffing decisions for foreign affiliates rather than the linear relationships as in most previous research.

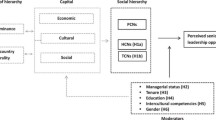

This paper empirically examines how the host country experience of Japanese MNCs moderates the linear relationship between firm characteristics and executive staffing decisions for foreign affiliates. A survey of 482 Japanese affiliates located in Korea was conducted in 2002. Our results show that while the level of global integration and the degree of centralization of decision-making have their main effects on the appointment of PCNs as executive directors at foreign affiliates, the host country experience of the affiliates significantly moderates the relationships. In particular, we find that the positive effects of the level of global integration and the degree of centralization of decision-making become weaker as foreign affiliates accumulate more experience in a host country. We believe that these moderating effects will provide more detailed explanations on the expatriation decisions of Japanese MNCs. In the following sections, we review the existing literature on MNCs’ staffing policies for foreign affiliates and develop research hypotheses. We then discuss data, research method and empirical findings. Finally, we summarize implications for researchers and practitioners and suggest some guidelines for future research.

Literature review

As MNCs continuously expand their business scope into global markets, a variety and complexity of international operations make it practically impossible for them to rely on traditional human resource management practice. To maximize the efficiency of global operations, staffing decisions for foreign affiliates have been among the most critical managerial tasks for MNCs since the 1970s. Reflecting the business world, early studies on staffing decisions for foreign affiliates highlighted the differences between PCNs and HCNs and their impact on corporate performance (e.g., Tung, 1982, 1984). Tan and Mahoney (2004) recognized PCNs and HCNs as two types of human resources for MNCs and provided theoretical explanations about the differences. Compared to HCNs, headquarters may expect PCNs to better perform critical functions, such as control over foreign affiliates or coordination of global operations, since they may better understand, assimilate and internalize common values, beliefs, assumptions and goals of their parent firms (e.g., Bonache, Brewster, & Suutari, 2001; Delios & Björkman, 2000). The literature suggests that the use of PCNs helps better align the economic incentives between headquarters and foreign affiliates (Cray, 1984; Kobrin, 1988; Ouchi, 1979; Tan & Mahoney, 2004). It is further argued that the use of PCNs may decrease uncertainty for headquarters in foreign operations since they can better predict the decision-making behavior of PCNs than of HCNs (Boyacigiller, 1990; Eisenhardt, 1985; Ouchi, 1979; Tan & Mahoney, 2004). Moreover, PCNs are viewed as having firm-specific capabilities such as personal relationships with headquarter managers, firm-specific information channels, knowledge of internal operating processes and so on (Festing, 1997; Tan & Mahoney, 2004).

Another stream of research on staffing policies for foreign affiliates has investigated why MNCs prefer to send PCNs to their foreign affiliates rather than HCNs (Edström & Galbraith, 1977; Tung, 1982, 1984). Edström and Galbraith (1977: 253) provided the first theoretical framework to explain why transfer of managers occurs across borders. They suggested three reasons for dispatch of expatriates; to fill positions, to develop managers and to develop organizations. The first motivation for transferring PCNs—to fill positions—is reasonable when qualified local managers are not available in a host country. Subsequent research further confirmed this motivation in various industries (Daniels & Radebaugh, 1998; Edström, 1994; Edstöm & Galbraith, 1977; Kobrin, 1988; Richards, 2001). The second motivation, that of developing managers, occurs when MNCs need to develop an international perspective and the skills of their future managers, which is further investigated by other studies (Daniels & Radebaugh, 1998; Edström, 1994; Kobrin, 1988; Richards, 2001). The third motivation, that of developing organizations, suggests that MNCs prefer to transfer PCNs for better control and coordination of their dispersed foreign operations. In particular, this argument (i.e., the third motivation) provided a broad foundation for further investigations in the following decades (e.g., Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005; Boyacigiller, 1990; Delios & Björkman, 2000; Harzing, 2001a, 2001b).

Japanese MNCs are well known for extensive reliance on PCNs for staffing at foreign affiliates (e.g., Delios & Björkman, 2000). A body of research on Japanese MNCs provides various explanations for the heavy reliance on PCNs. Tung (1984) suggested that due to the unique Japanese management systems such as lifetime employment and seniority, there is a psychological reluctance to the hiring of foreign managers. Bartlett and Yoshihara (1988) argued that the Japanese staffing practice for foreign affiliates results from their management process. They suggested that unlike the more system-oriented approach in American-based firms, people-dependent and communication-intensive Japanese management processes cannot be easily transferred across barriers of distance, time, language and culture. Other studies find reasons for Japanese practices of human resource management at foreign affiliates in control and communications. Jaeger and Baliga (1985) explained the Japanese control system as a culture-intensive system. The culture-intensive control systems utilize employees’ internalization of and moral commitment to a firm’s norms, values, objectives and ways of doing things. In the culture-intensive control system, they suggested that output is controlled by shared norms of performance and behavior is usually guided by a shared managerial philosophy. Jaeger (1983) argued that due to the heavy reliance on the culture-intensive control system, Japanese MNCs are more likely to use PCNs for foreign affiliates.

Another feature of Japanese management characteristics that may affect staffing policies for foreign affiliates is the intensive inter-organizational linkages within vertically organized industrial groups centered around major manufacturing firms such as Hitachi, Sony or Toyota (e.g., Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005; Gerlach, 1992; Sako, 1996, 1999). Due to these strong linkages, Japanese firms tend to extend an internal labor market to group firms in a vertically organized group called a keiretsu. Through posting of managers, core firms in a keiretsu may maintain a certain level of control over other firms in the group, which is often supplemented with partial equity ownership or financial loans. Sako (1996) shows that about 25 member firms in the Japanese auto maker group, Toyota, have members of their board of directors who formerly worked for Toyota. Sako (1999) argues that the intra-group job rotation schemes can be a Japanese mechanism to diffuse tacit managerial skills and knowledge within groups. To the extent that this system of rotating managers within group firms is replicated across borders, this form of inter-firm interdependence may affect expatriate assignment decisions. In particular, Belderbos and Heijltjes (2005) showed that the manufacturing network size of the keiretsu in a host country significantly affects the likelihood that Japanese MNCs assign PCNs as managing directors of their affiliates in Asian countries. They argued that a large manufacturing network established by other group firms in a host country may promote sharing of relevant country-specific knowledge among group firms.

However, except for a few studies (e.g., Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005; Delios & Björkman, 2000), most of the previous research on Japanese MNCs has consisted of descriptive or conceptual studies rather than empirical investigations. Compared to our common understanding on Japanese MNCs’ staffing practices for foreign affiliates, it is somewhat surprising that there has been a relatively scarce effort into empirical research. Delios and Björkman (2000) analyzed 797 Japanese manufacturing subsidiaries in China and the US in 1996. They argued that Japanese MNCs rely on PCNs rather than HCNs for better control over and knowledge transfer to foreign affiliates. They empirically showed that Japanese MNCs tend to use more PCNs when they have high equity ownership, more experience in host countries and more resources at the headquarters. Furthermore, a few recent empirical studies have reported contradictory findings to our general understanding of Japanese MNCs’ staffing practices for foreign affiliates. Beamish and Inkpen (1998) investigated changes in the number of PCNs in foreign affiliates of Japanese MNCs from 1960 to 1993. Contrary to conventional knowledge, they reported that the number of Japanese PCNs decreased. Their explanation is that Japanese MNCs have had no other choice because of the limited supply of PCNs. They further explained that Japanese MNCs have begun to recognize the importance of empowering local managers in global competition. Delios and Björkman (2000) also showed that the use of PCNs by Japanese MNCs depends on locations. They reported that the use of PCNs was more extensive in subsidiaries in China than in the US. Jaussaud, Schaaper and Zhang (2001) reported that Japanese firms send more PCNs to developing countries than to industrialized countries since qualified managers are usually less available in developing countries. Belderbos and Heijltjes (2005) also reported that several factors decrease the likelihood for Japanese MNCs to use PCNs in Asian countries. Those factors include the local orientation of foreign affiliates, an affiliate’s experience in cooperating with its parent firm, the prior experience of parent firms in host countries and the size of the manufacturing network of the keiretsu in host countries.

These studies show that conventional wisdom on Japanese staffing policies for foreign affiliates seems not only controversial but is also confusing. It indicates that Japanese practices may be much more complicated than we have assumed. The current gap between our understanding and Japanese practices may result from the fact that most previous studies on Japanese MNCs examined simple linear relationships between the use of PCNs and several predictors. It now seems that further studies are necessary to examine the complex mechanisms of Japanese MNCs’ staffing policies for foreign affiliates. Therefore, unlike previous studies that examined mostly linear relationships, our study investigates how a few explanatory variables in previous studies interact to deliver an impact on expatriation decisions. Specifically, our study investigates how the host country experience moderates the impact of the level of global integration, the degree of centralization of decision-making and the host country dependence on the use of PCNs for executive positions at foreign affiliates. We believe that our research may bridge the gap between common understanding and the factual practice of Japanese firms. The following section develops hypotheses for our study.

Hypotheses

Foreign affiliates of most MNCs tend to face two kinds of pressure, global integration for maximum efficiency of their entire global network and local responsiveness for better adaptation to differences across countries (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1998). The global integration strategy usually relies on standardized and consistent procedures across countries, which may tend to impose the decision-making rules of the headquarters on foreign affiliates. It thus places the first priority on the efficiency of their entire global network rather than that of local affiliates. Otherwise, it is very likely that the misalignment of economic incentives between headquarters and foreign affiliates, mis-coordination among foreign affiliates and information asymmetry problems may occur (Tan & Mahoney, 2004). Accordingly, the amount of the global integration pressure may affect decisions of headquarters concerning executive positions at foreign affiliates. For example, MNCs that want to enjoy the benefits of a global integration strategy may tend to staff executive positions at foreign affiliates with PCNs rather than HCNs. PCNs are known for having better control over foreign affiliates, better coordination of foreign operations and better alignment of the economic incentives between headquarters and foreign affiliates, since they may assimilate and internalize common values, beliefs, assumptions and goals of their parent firms (e.g., Bonache et al., 2001; Boyacigiller, 1990; Cray, 1984; Delios & Björkman, 2000; Eisenhardt, 1985; Kobrin, 1988; Ouchi, 1979). In addition, PCNs may have other advantages in MNCs with global integration strategies since they have personal relationships with headquarter managers, firm-specific information channels and knowledge of internal operating processes (Festing, 1997; Tan & Mahoney, 2004). Thus, the global integration of foreign operations may increase the likelihood of the use of PCNs for executive positions at foreign affiliates. In particular, for Japanese MNCs known for unique human resource management practices, the higher level of integration of a foreign affiliate to the MNC’s global operations will drive the use of PCNs as the affiliate’s executive directors. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 1a

As the level of global integration for Japanese MNCs increases, they are more likely to assign PCNs to executive positions in their foreign affiliates.

However, a preference to use PCNs may depend on the experience of foreign affiliates in a host country, since foreign affiliates are able to collect knowledge about local markets, develop training procedures and establish location-specific management systems over time (e.g., Delios & Björkman, 2000; Jaeger, 1983; Mezias & Scandura, 2005). Previous studies on the experience of foreign affiliates showed mixed findings. For example, Delios and Björkman (2000) showed that Japanese MNCs were willing to devote more PCNs to the foreign affiliates when they developed knowledge of the host country environment in China and the US. On the other hand, Belderbos and Heijltjes (2005) reported that Japanese MNCs are less likely to assign PCNs when they have more experience in local markets. These mixed findings imply that the experience of foreign affiliates may have a more complicated influence rather than a simple linear impact on staffing policies for the affiliates.

We suggest that the experience of foreign affiliates may moderate the positive relationship between an imperative of global integration and the likelihood to assign PCNs to executive positions at foreign affiliates. While Japanese MNCs experience a strong demand to integrate foreign operations, it may be often a precondition of global integration for them to obtain sufficient knowledge about a host country. Without knowledge about how to manage an organization within a local context, it may not be easy to create global efficiency that arises partly from efficient operations of each foreign affiliate. For an acquisition of local knowledge, Japanese MNCs may need to rely on HCNs, especially at the initial stage. However, once the need for local knowledge is satisfied to a certain level, then Japanese MNCs may come across a new type of need for expedited global integration such as global coordination, communication, information sharing and control. For this new type of need, previous studies reported increased efficiency when organizations have similar prior knowledge, compatible norms and values and similar logic (e.g., Bettis & Prahalad, 1995; Bonache et al., 2001; Boyacigiller, 1990; Delios & Björkman, 2000; Ouchi, 1979). Rodgers and Wong (1996) also showed that the reliance on PCNs may function as an alternative to the transfer of Japanese-style human resource management practices. In addition, as foreign affiliates accumulate local experience, like HCNs, PCNs can better predict performance of affiliates’ operations based on past records and efficiently exercise control over them. These imply that, over time, the need for better coordination, communication and control may dominate the need for local knowledge and therefore the need for PCNs may also increase. Thus, we predict as follows:

Hypothesis 1b

The positive relationship between the level of global integration and the use of PCNs becomes stronger as foreign affiliates accumulate more experience in the host country.

MNCs that rely extensively on centralized decision-making often tend to exploit the benefits of efficient communication within their global networks (Barlett & Ghoshal, 1998). Efficient communication between headquarters and foreign affiliates is another factor that may affect the overall performance of foreign affiliates. For accurate and timely interpretation of messages across borders, managers in foreign affiliates have to correctly understand the practical meaning of headquarters’ decisions and abide by them. Good communication takes place when both parties have similar backgrounds and assumptions (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Kogut & Zander, 1993). PCNs may have an advantage over HCNs in communication effectiveness because they have the same social and cultural background as managers in headquarters. A long process of socialization that possibly occurred at a parent firm may also alleviate the possible incidence of misunderstanding and miscommunication. In addition, for effective implementation of headquarters’ decisions, managers in foreign affiliates should avoid a possible misalignment of economic incentives between headquarters and foreign affiliates. For example, IBM had to deal with strong resistance among European managers in 1994 when a new CEO, Louis Gerstner, Jr., introduced an entirely different structure for global organization. Previous studies reported that the use of PCNs may alleviate these kinds of possible incentive misalignment problems (e.g., Cray, 1984; Ouchi, 1979; Tan & Mahoney, 2004). These discussions imply that centralization of decision-making functions well when PCNs are extensively used for executive positions at foreign affiliates.

Hypothesis 2a

As the level of centralization of decision-making increases, Japanese MNCs are more likely to assign PCNs to executive positions in their foreign affiliates.

The positive relationship between a centralized decision-making practice and a tendency to use PCNs may be moderated by experience of foreign affiliates in host countries. In the early stage of foreign affiliates, even for Japanese MNCs that centralize their decision-making at headquarters, they are more likely to rely on PCNs for timely communication with the affiliates and efficient implementation by the affiliates of headquarters’ decisions because they have to install complete communication procedures and implementation systems in the affiliates. When appropriate procedures and systems are not stabilized, the communication and execution processes held between Japanese headquarters and HCNs may require significant amounts of time and effort. However, foreign affiliates may develop their own communication procedures with headquarters through learning-by-doing over time (Downes & Thomas, 2000; von Hippel & Tyre, 1995). Once these procedures and systems kick in, the possible incidence of miscommunication and incentive misalignment may be alleviated to a certain level, reducing the advantages of PCNs over HCNs. Thus, we predict:

Hypothesis 2b

The positive relationship between the level of centralization of decision-making and the use of PCNs becomes weaker as foreign affiliates accumulate more experience in the host country.

One of the factors that affect staffing policies for foreign affiliates is the characteristics of a host country itself. Previous studies have examined a few aspects of the host country, such as political risk (e.g., Boyacigiller, 1990), cultural distance (e.g., Harzing, 2001b), education level (e.g., Scullion, 1991) and so on. However, the importance of local markets to foreign affiliates has been under-represented in most previous studies. Whether or not a foreign affiliate is established mainly for business in a specific host country may have a critical impact on the choice between PCNs and HCNs. For example, when a foreign affiliate sells most of its products in a specific host country, it then needs a significant amount of knowledge about the local market. The knowledge requirement may drive the affiliate to choose HCNs rather than PCNs. HCNs generally possess better knowledge of the local context including cultural, economic, political and legal aspects (Harzing, 2001b; Kobrin, 1988). They are also known to better negotiate with local suppliers and buyers (Beamish & Inkpen, 1998). Conversely, when a foreign affiliate creates most of its revenue outside the host country, it may have more flexibility in staffing its executive positions. Egelhoff (1988) suggested that as the amount of local information processing increases, foreign affiliates should have more discretion to deal with local market-specific issues. In such situations, HCNs possessing more local knowledge may be preferred to PCNs. Belderbos and Heijltjes (2005) empirically showed that the local market orientation of foreign affiliates has a negative impact on the choice of PCNs for managing director positions at the affiliates. Thus, we predict:

Hypothesis 3a

As foreign affiliates are more dependent on host country markets, Japanese MNCs are less likely to assign PCNs to executive positions in their foreign affiliates.

While a heavy dependence on host country markets may increase the probability that Japanese MNCs will assign HCNs rather than PCNs to executive positions at foreign affiliates, the magnitude of such reliance may be affected by a foreign affiliate’s experience in a host country for several reasons. First, foreign affiliates themselves can be a learning organization collecting knowledge about host country specific contexts and ways to manage business relationships in local markets (e.g., Bird, 1996; Downes & Thomas, 2000; von Hippel & Tyre, 1995). The collected knowledge can be systemized within foreign affiliates in the forms of processes and documents over time, converting tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge (e.g., Grant 1996; Gupta & Govindarajan, 1991). As foreign affiliates systemize the collected knowledge, the potential advantages of HCNs over PCNs may decrease over time. Second, the collected knowledge may flow back and forth between headquarters and foreign affiliates. Previous studies suggested that transfer of a parent firm’s knowledge or corporate culture to foreign affiliates is an essential function fulfilled by expatriate managers (Delios & Björkman, 2000; Jaeger, 1983). Likewise, the transfer of knowledge from foreign affiliates to headquarters is also possible through on-going interactions between HCNs and PCNs within foreign affiliates. Through these knowledge transfer processes, headquarters may better understand local conditions that are dealt with by foreign affiliates and be able to better predict decisions made by them. Third, PCNs may be able to learn location specific knowledge of HCNs by watching and imitating their practices over time (e.g., Huber, 1991; Levinthal & March, 1993; Miner & Haunschild, 1995; Simonin, 1997). These discussions suggest that the advantage of HCNs over PCNs in dealing with the pressure for local responsiveness would be attenuated over time. Thus, we predict:

Hypothesis 3b

The negative relationship between the dependence of foreign affiliates on host country markets and the use of PCNs becomes weaker as they accumulate more experience in the host country.

Method

Data

We conducted an empirical study using data on Japanese firms’ affiliates located in Korea. We collected a part of the data necessary for hypothesis testing from the following two books. The Kaigai Shinshutsu Kigyo Soran 2002 (The Yearbook of Japanese Investments Overseas, hereafter Soran), published by Toyo Keizai Shinposha, provides data on Japanese firms’ affiliates located in Korea. Through Soran, we identified 482 affiliates located in Korea that were owned by 425 Japanese firms. The Kaisha Shikiho (The Corporate Quarterly Handbook), published by Toyo Keizai Shinposha, provides data on Japanese parent firms. These two books provide primary data for this study. To collect additional data, we conducted a survey in 2002. While the original questionnaire was developed in Japanese, we went through translation and back-translation processes to eliminate possible measurement errors (Shortell & Zajac, 1990). It was then reviewed and revised through pilot interviews with Japanese expatriate managers in Korea. We directed the survey questionnaire to either heads or executive members of Japanese affiliates in Korea. The questionnaire, with a total of 35 questions, was sent to 482 Japanese affiliates and 111 affiliates responded at a rate of 23.0%. The response rate of 23.0% was not significantly low compared to other studies in this field (e.g., Bird & Beechler, 1995; Peterson et al., 1996). Missing data on some variables reduced the number of usable samples from 111 to 103. Significant differences between those firms that responded and non-responders were checked by t-tests. T-values between the two groups were 0.482 (p ≤ 0.630) for the number of employees in foreign affiliates and 0.557 (p ≤ 0.578) for years from establishment, respectively. Our final sample includes both manufacturing and non-manufacturing Japanese affiliates. Since our entire sample consisted of Japanese affiliates in Korea, we did not control for country-specific factors such as cultural distance, cost of living, educational level and so forth.

Measures

Dependent variable

A dependent variable is the ratio of PCNs among executive directors at a Japanese affiliate in Korea. The data was collected through our survey. Against our expectation, we did not come across executive directors from a third country in this study. It may be because Korea is not geographically far away from Japan or because Japanese MNCs may prefer HCNs or PCNs rather than managers from third countries. In addition to the ratio variable, even though we did not report the results in tables, we examined whether or not using nationality of an affiliate’s CEO as a dependent variable makes any difference in an empirical analysis. The CEO nationality was coded as 1 when he/she was a Japanese national, while it was coded as 0 otherwise. We report these results in the “Robustness checks” section.

Independent and moderator variables

The level of global integration

There are various ways to measure the level of global integration. However, in this study, we measured it by using intra-firm sales as a percentage of total sales, and intra-firm procurement as a percentage of total procurement, of an affiliate. We also used the average of the above two items. In the empirical analysis, we did not find any significant difference between the two different approaches. Thus, we reported the statistical results of an empirical study that used the average value of the two items.

Degree of centralization of decision-making

To measure the degree of centralization of decision-making, we asked the degree to which decision-making is centralized at headquarters in terms of the following eight areas: strategy planning, investment, marketing, procurement, production, R&D, financing and personnel management. Respondents were required to answer these questions on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (centralized on an affiliate) to 5 (centralized on headquarters). The average value of eight items was used as the measure for the degree of centralization of decision-making. Since there may be a different preference of centralization across various managerial functions (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1998), to check the robustness of this measure, we have used different measurement methods, such as using the average of only a few items. However, we could not find any significant changes in analytical results.

Dependence of foreign affiliates on host country markets

We measured foreign affiliates’ dependence on host country markets by using the share of host country sales in the total sales of a foreign affiliate. If an affiliate conducts its business exclusively for a local market, local market-specific knowledge may become much more important than when the affiliate aims its sales mostly outside the local market (e.g., Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005). We also measured a foreign affiliate’s dependence on host country markets in terms of production input by using the share of host country purchase in total purchase of a foreign affiliate. We confirmed very similar results to the host country sales variable; however, we do not report the analysis results using the host country procurement variable.

Experience of foreign affiliates in a host country

The experience of foreign affiliates in a host country may depend on how long they have been in operation in the country (Delios & Beamish, 1999). The length of firm operation has been known to affect various corporate activities such as alliances, survival, profitability, international expansion and exposure to liabilities of foreignness (e.g., Autio, Sapienza, & Almeida, 2000; Mezias, 2002). To capture the length of operation, we used the number of years during which a foreign affiliate has been in operation in Korea. We also measured the length of operation using a logarithm of the number of years from an affiliate’s incorporation. Additional analyses confirmed that using the logarithm did not significantly alter the analytical results.

Control variables

We controlled for international experience of Japanese MNCs because it may affect staffing policies for executive positions at foreign affiliates through an accumulation of global management experience. We measured international experience of Japanese parent firms by the log of the total number of a parent firm’s foreign affiliates worldwide in the year 2002. We also controlled for size of foreign affiliates and Japanese parent firms’ ownership in their foreign affiliates, since large and majority-owned foreign affiliates may be more important to a parent firm than others (Harzing, 2001b). To measure the size of foreign affiliates, we used the number of employees in a foreign affiliate divided by the number of employees in its parent firm (Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005; Delios & Björkman, 2000).

For the measurement of ownership, we used a categorical variable that was coded 1 for minority-owned, 2 for co-owned (i.e., 50:50 ownership), 3 for majority-owned, and 4 for wholly-owned. We also measured this by using a ratio of equity shares possessed by a Japanese parent firm (e.g., Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005). In addition, we made a dummy variable coded 1 when a Japanese parent firm possesses a minority stake and 0 for otherwise. Additional analyses using these two measures did not find any significant difference from the results reported in the tables.

Additionally, we controlled for the industry effect by using a dummy variable coded 1 for non-manufacturing industries and 0 for otherwise. Because Japanese service and trading firms are often known to use a large number of PCNs in foreign affiliates (Beamish & Inkpen, 1998), we controlled for these two industries. We also incorporated two more control variables concerning the context of Korean markets, the possible incidence of labor-union strikes and the infringement of intellectual property rights. To measure these two additional variables, we asked respondents to evaluate those risks on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for variables used in this study. It shows that 65% of executive positions at affiliates in Korea are filled by PCNs for our sample. This is a consistent finding with previous studies that reported on the ethnocentric staffing policies of Japanese firms. For example, Belderbos and Heijltjes (2005) reports that for foreign affiliates in nine Asian countries, 70% of managing directors are Japanese. However, in terms of CEO positions at the 103 responding affiliates, PCNs were CEOs only for 57 affiliates, which is fairly low, and HCNs for 46 affiliates. The fact that 46 CEOs are HCNs may result from the long operation history of those Japanese affiliates in Korea. The average number of employees at affiliates was 179 while the average number of total employees of parent firms was 20,084. In terms of ownership structure for foreign affiliates, parent firms possessed 78% of equity ownership on average.

The correlations among explanatory variables are not particularly high except the one between level of global integration and degree of centralization of decision-making (r = 0.654, p < 0.001). Checking variance inflation factors (VIF) and tolerance level, we found that these two variables have a potential to cause multicollinearity problems (Belsley, Kuh, & Welsch, 1980). Considering various guidance that deals with multicollinearity issues (Kennedy, 1998), we decided to use two base models for hypothesis testing in this study (Models 1a and 1b). Despite moderate to low correlations across explanatory and control variables, we conducted additional analyses by entering or dropping control variables sequentially to confirm that multicollinearity did not threaten coefficient estimates. We also confirmed that all VIF scores were less than 2.

A Tobit model was used to test our hypotheses because we adopted a ratio dependent variable. A Tobit model is preferred to ordinary least squares regression (OLS) analysis when a dependent variable is censored at some value on the left and/or right side because OLS can lead to biased coefficient estimates (Delios & Henisz, 2000). A double-censored Tobit model was employed for this empirical study. Table 2 presents the results of a Tobit regression analysis for the choice of executive director positions at foreign affiliates. Models 1a and 1b show the results of base models including main explanatory and control variables. Among control variables, a parent firm’s ownership in its foreign affiliates and a possibility of labor-union strikes had a significant impact on the use of PCNs. Unlike some previous findings (e.g., Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005; Harzing, 2001b), we found that industry classification and size of foreign affiliates were not significant. In addition, unlike the findings of Delios and Björkman (2000), we did not find that international experience of parent firms and concerns about infringement of intellectual property rights had a significant impact on the choice of executive directors at affiliates in Korea. However, Japanese MNCs are likely to be concerned about the possible incidence of labor-union strikes, for which they choose to rely more on PCNs rather than HCNs. Consistent with previous studies (Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005; Delios & Björkman, 2000; Harzing, 2001b), we found that the parent firms’ ownership in their foreign affiliates had a positive impact on the use of PCNs.

As shown in Model 1a, the level of global integration was significantly and positively (p < 0.01) associated with the use of PCNs. Its impact remained significant in subsequent models that included the interaction effects of affiliates’ experience in a host country and other main variables. These results support H1a, indicating that the more a foreign affiliate is integrated into the global operations of a parent firm, the more likely that a Japanese MNC assigns PCNs to executive positions in its foreign affiliate. In addition, Model 1b indicates the positive and significant impact of the degree of centralization of decision-making on the use of PCNs. This supports H2a that implies that when decision-making on managerial issues of a foreign affiliate is centralized at headquarters, it is likely that more PCNs are assigned as its executive directors. However, another explanatory variable, dependence of foreign affiliates on host country markets, was not significant in Models 1a and 1b. The variable remained insignificant in subsequent models as well. These results do not support H3a, implying that dependence of foreign affiliates on host country markets does not have a critical impact on Japanese MNCs’ executive staffing decisions for foreign affiliates. While we did not develop a hypothesis on the direct influence of host country experience of foreign affiliates, we found that it had a significant and negative association with the use of PCNs. This is consistent with findings of some previous studies (e.g., Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005; Harzing, 2001b) but contradicts those of others (Delios & Björkman, 2000).

Model 2 includes the interaction term between the level of global integration and experience of foreign affiliates in a host country. Unlike our prediction, the coefficient of the interaction term was negative (p < 0.01). This result does not support H1b, indicating that the positive relationship between an imperative of global integration and the use of PCNs does not become stronger as foreign affiliates accumulate more host country experience. However, this significant and negative interaction term suggests an interesting finding about the choice of an affiliate’s executive directors by Japanese MNCs. It indicates that for foreign affiliates with less experience in a host country, an imperative of global integration drives Japanese MNCs to rely on PCNs rather than HCNs. In contrast, for those with more host country experience, headquarters seem to assign more HCNs as executive directors even when the level of global integration is high. Model 3 includes the second interaction term between the degree of centralization of decision-making and the host country experience of foreign affiliates. As we predicted, the coefficient of the interaction term was negative and significant (p < 0.001). This result supports H2b, indicating that a positive relationship between the degree of centralization of decision-making and the use of PCNs becomes weaker as foreign affiliates accumulate more host country experience. It seems that for foreign affiliates with less host country experience, centralization of decision-making drives Japanese MNCs to rely on PCNs rather than HCNs. However, as host country experience is accumulated, a tendency to staff executive positions with PCNs declines even under centralized decision-making. Models 4a and 4b include the last interaction term between a foreign affiliate’s dependence on host country markets and its host country experience. Unlike our prediction, the coefficients of the interaction terms in both models were not significant. This result does not support H3b, and cannot confirm the moderating effect of host country experience on the relationship between a foreign affiliate’s dependence on local markets and the use of PCNs.

Robustness checks

We conducted additional analyses to check the robustness of our findings. First, we examined whether using nationality of an affiliate’s CEO, instead of executive directors, as a dependent variable makes any difference in empirical results. In a similar way with an analysis presented in Table 2, we conducted logistic regressions using the CEO nationality as a dependent variable. The analysis results remained almost the same as those of a Tobit analysis except that there were some minor changes in the level of significance for one of the interaction effects. These results reconfirmed our findings in the previous section. Second, for the coding of equity ownership, we conducted Tobit regression analyses with four different measures including dummy variables for 50:50, 51% or more, 75% or more, and 100 % ownership. The coefficients and standard errors for main and interaction effects remained almost consistent with those reported in Table 2, although the inclusion of these dummy variables slightly changed the models’ explanatory power. Third, the sample selection is a potential concern because the response rate to our survey (23.0%) was not very high. Thus, we conducted t-tests for responding and non-responding groups in terms of the number of employees in a foreign affiliate and years since an affiliate’s foundation, and could not find any significant difference between the two groups (T-values were reported in the “Method” section). We also repeated the same Tobit analysis for the randomly selected affiliates and checked if the sample selection has created any significant difference. Except for slight decreases in the significance levels, the coefficients for main and interaction effects remained significant in the additional analysis. Lastly, as we reported in the “Method” section, we conducted more analyses by using different measures for key variables. While we did not report the results of those additional analyses here, we confirmed that most of our findings were robust to these changes.

Discussion and conclusion

An item of conventional wisdom about Japanese firms’ practices of expatriation indicates a heavy reliance on PCNs (Bartlett & Yoshihara, 1988; Delios & Björkman, 2000; Jaeger, 1983; Tung, 1984). However, some recent empirical findings provided both controversial and mixed evidence in relation to common understanding (Beamish & Inkpen, 1998; Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005; Delios & Björkman, 2000; Jaussaud et al., 2001), which implies that their practices may be much more complicated than is commonly assumed. These complexities may reside in the fact that most previous studies on Japanese MNCs relied on linear relationships to explain their staffing policies for foreign affiliates. Thus, unlike previous studies, we investigated how the interactions of those explanatory variables affect Japanese MNCs’ staffing policies for foreign affiliates. In particular, our study investigated how the experience of foreign affiliates in a host country moderates the impact of three key variables on Japanese firms’ expatriation decisions, which include an imperative of global integration, centralized decision-making and dependence on host country markets.

First of all, our study found that 65% of executive positions at Japanese affiliates in Korea were filled by PCNs which is fairly consistent with previous studies. The heavy reliance on PCNs may be partially explained by the fact that Japanese MNCs may tend to maintain tight control over their foreign affiliates (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1998). We also found that the level of global integration and centralization had a positive impact on the use of PCNs for executive directors at foreign affiliates. However, we found that dependence of foreign affiliates on host country markets did not have a critical impact on Japanese MNCs’ staffing policies for foreign affiliates. We further found that experience of foreign affiliates in a host country had a significant and negative association with the use of PCNs. In terms of control variables, concern about possible labor strikes and the ownership structure of foreign affiliates seem to affect expatriation decisions of Japanese MNCs. However, we found that industry classification, size of foreign affiliates, international experience of parent firms and concerns about the infringement of intellectual property rights did not have a significant impact on the choice of executive directors at foreign affiliates. Some of these findings are consistent with those of previous studies while others are not. These mixed findings show that we need to apply a new approach to investigate the above relationships.

The analysis of our interest lies in the interaction effect between experience of foreign affiliates in a host country and the three main predictors. Findings about the first interaction effect between the level of global integration and experience of foreign affiliates in a host country show that for foreign affiliates with less host country experience, their executive directors tend to be staffed with PCNs rather than HCNs when they are integrated into global operations of their parent firm. However, our findings show that as foreign affiliates accumulate more experience in a host country, Japanese firms tend to give up such policy and staff them with more HCNs. In addition, our findings concerning the second interaction effect between the degree of centralization of decision-making and experience of foreign affiliates in a host country show that when foreign affiliates have less experience in a host country, Japanese MNCs tend to assign PCNs as executive directors at such affiliates in order for them to better function within a centralized decision-making system. However, as foreign affiliates learn more about the host country, they can use more HCNs for executive positions. These findings imply that while Japanese headquarters may be actively involved in executive staffing decisions for foreign affiliates in the early stages, they tend to become less involved over time. In this way, they can reduce the overall management costs in foreign countries because the cost of expatriate managers is usually more expensive than local personnel (Benito, Tomassen, Bonache-Pérez, & Pla-Barber, 2005; Gates, 1996; Tarique, Schuler, & Gong, 2006). Thus, in the long-term perspective, Japanese MNCs may tend to gradually delegate a significant amount of authority to their foreign affiliates.

However, we found that the last interaction effect between foreign affiliates’ dependence on local markets and the experience of foreign affiliates in a host country was not significant. This finding suggests two possible explanations. The one is that the Japanese staffing decisions for foreign affiliates are more affected by other dimensions such as the level of global integration, centralization of decision-making and host country experience rather than local market dependence. The other might be that even though the Korean market is very close to Japan, the market itself may not be a very significant portion of the total revenue of Japanese MNCs. If the second explanation reflects the reality, then the local market dependence variable may have an entirely different impact in other countries.

Overall, our findings on the three interaction effects show that to explain Japanese firms’ staffing policies for foreign affiliates, we need to investigate both main and interaction effects of predictors. Specifically, our study found the importance of the host country experience as a moderator for the relationships between global integration and centralization and the use of PCNs. To further understand the effect of the host country experience, it will be necessary to investigate an evolutionary process of executive staffing decisions for foreign affiliates. Although we adopted a cross-sectional research design, future research should employ longitudinal methods to examine how executive staffing policies for foreign affiliates change as host country experience is accumulated. Our study also suggests that the theoretical foundation of staffing policies for foreign affiliates may be enriched by considering influences of interaction effects. Most previous studies highlighted the linear associations between organizational characteristics and expatriation decisions in the perspective of knowledge and learning (e.g., Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005; Delios & Björkman, 2000), managerial controls (e.g., Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005; Delios & Björkman, 2000) and agency costs (e.g., Gong, 2003). Our empirical study found significant moderating effects of the host country experience on some linear relationships. Future research will explore and identify several moderating effects to better depict the complexity of staffing policies for foreign affiliates.

From the managerial standpoint, our findings suggest that for executive directors at foreign affiliates, Japanese MNCs do selectively recruit PCNs or HCNs depending on the length of their experience in host countries. In particular, when their foreign affiliates accumulate more experience in a host country, Japanese MNCs tend to use more HCNs for executive positions at the affiliates even at a high level of global integration and centralization. These findings show that while the practices of Japanese MNCs look different than those of US MNCs in the short-term perspective, they are fairly similar in the long-term perspective. Miles and Snow (1978) articulated how organizations make strategic decisions by simultaneously taking into account their capabilities, environments and processes. Our study clearly shows that Japanese MNCs could benefit from accounting for experience of their foreign affiliates in host countries when dealing with executive staffing issues for foreign affiliates. Thus, to understand executive staffing practices for foreign affiliates, managers have to expand their research frameworks to include both headquarter and foreign affiliate characteristics.

Even though our study extended previous studies by investigating moderating effects of the host country experience, it is subject to several limitations. First, the context of our study is limited. The scope of our analysis is constrained to Japanese affiliates in Korea, thus we cannot simply generalize our findings across other countries. Therefore, future studies can retest these findings in the context of other or multiple countries. In addition, while we could not find significant differences across industries, future studies may need to confirm whether industry types or different stages of industrial development may change current findings.

Second, our research relied on a cross-sectional survey to collect data. Given that our main variable of interest was experience of foreign affiliates in a host country, future studies may investigate and confirm the current findings by analyzing longitudinal data. Longitudinal data may allow researchers to employ more rigorous empirical analysis methods. In addition, future studies may need to collect data from both headquarters and foreign affiliates. In particular, simultaneous observation of headquarters and foreign affiliates may provide more enriched explanations about executive staffing issues for foreign affiliates.

Third, our results confirm the relevance of moderating variables but not the role of environmental conditions. Strategies typically depend on both internal and external factors, among which environmental conditions may have critical influence. External environments are classified into various dimensions, such as munificence, dynamism, complexity and uncertainty (Dess & Beard, 1984), and some of these dimensions have been further divided (Castrogiovanni, 1991; Sutcliffe & Zaheer, 1998). Each may constitute a critical environmental condition that affects or moderates strategic actions and their outcomes (Park & Mezias, 2005; Simerly & Li, 2000). Although our research focuses mostly on internal aspects of Japanese MNCs, future research may incorporate critical environmental dimensions to better examine staffing practices for foreign affiliates.

Finally, while we could not include the performance implications of staffing policies for foreign affiliates, future studies may definitely need to examine the impact of the staffing policies on the performance of foreign affiliates. The addition of performance variables may significantly improve managerial implications from academic research for most MNCs. Furthermore, even though it may be challenging, researchers may want to find ways to derive the effects of expatriation decisions on long-term performance. These future studies will significantly contribute to the further enhancement of research on staffing policies for foreign affiliates.

References

Autio, E., Sapienza, H. J., & Almeida, J. G. 2000. Effects of age at entry, knowledge intensity, and imitability on international growth. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5): 909–924.

Baliga, B. R., & Jaeger, A. M. 1984. Multinational corporations: Control systems and delegation issues. Journal of International Business Studies, 15(2): 25–40.

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. 1998. Managing across borders (2nd ed.). Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press.

Bartlett, C. A., & Yoshihara, H. 1988. New challenges for Japanese multinationals. Human Resource Management, 27(1): 19–43.

Beamish, P. W., & Inkpen, A. C. 1998. Japanese firms and the decline of the Japanese expatriate. Journal of World Business, 33(1): 35–50.

Beechler, S., & Yang, J. Z. 1994. The transfer of Japanese-style management to American subsidiaries: Contingencies, constraints, and competencies. Journal of International Business Studies, 25: 467–491.

Belderbos, R. A. 1997. Antidumping and tariff jumping: Japanese firms’ DFI in the European Union and the United States. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 133(3): 419–457.

Belderbos, R. A., & Heijltjes, M. G. 2005. The determinants of expatriate staffing by Japanese multinationals in Asia: Control, learning and vertical business groups. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(3): 341–354.

Belsley, D. A., Kuh, E., & Welsch, R. E. 1980. Regression diagnostics: Identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. New York: Wiley.

Benito, G. R. G., Tomassen, S., Bonache-Pérez, J., & Pla-Barber, J. 2005. A transaction cost analysis of staffing decisions in international operations. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 21(1): 101–126.

Bettis, R. A., & Prahalad, C. K. 1995. The dominant logic: Retrospective and extension. Strategic Management Journal, 16(1): 5–14.

Bird, A. 1996. Careers as repositories of knowledge: Considerations for boundaryless careers. In M. B. Arthur & D. M. Rousseau (Eds.), The boundaryless career: A new employment principle for a new organizational era: 150–168. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bird, A., & Beechler, S. 1995. Links between business strategy and human resource management strategy in U.S.-based Japanese subsidiaries: An empirical investigation. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(1): 23–46.

Bonache, J., Brewster, C., & Suutari, V. 2001. Expatriation: A developing research agenda. Thunderbird International Business Review, 43(1): 3–20.

Boyacigiller, N. 1990. The role of expatriates in the management of interdependence, complexity and risk in multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 21(3): 357–381.

Buckley, P., & Casson, M. 1976. The future of multinational enterprise. London: Macmillan.

Castrogiovanni, G. J. 1991. Environmental munificence: A theoretical assessment. Academy of Management Review, 16(3): 542–565.

Cray, D. 1984. Control and coordination in multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 15(2): 85–98.

Daniels, J. D., & Radebaugh, L. H. 1998. International business environments and operations (8th ed.). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Delios, A., & Beamish, P. W. 1999. Ownership strategy of Japanese firms: Transactional, institutional, and experience influences. Strategic Management Journal, 20: 915–933.

Delios, A., & Björkman, I. 2000. Expatriate staffing in foreign subsidiaries of Japanese multinational corporations in the PRC and the United States. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(2): 278–293.

Delios, A., & Henisz, W. J. 2000. Japanese firms’ investment strategies in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3): 305–323.

Dess, G., & Beard, D. 1984. Dimensions of organizational task environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29: 52–73.

Downes, M., & Thomas, A. 2000. Knowledge transfer through expatriation: The U-curve approach to overseas staffing. Journal of Managerial Issues, 7(2): 131–149.

Edström, A. 1994. Alternative policies for international transfers of managers. Management International Review, 34(1): 71–82.

Edström, A., & Galbraith, J. R. 1977. Transfer of managers as a coordination and control strategy in multinational organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22: 248–263.

Egelhoff, W. 1988. Organizing the multinational enterprise: An information processing perspective. Cambridge, MA: Harper and Row.

Eisenhardt, K. M. 1985. Control: Organizational and economic approach. Management Science, 31(2): 134–149.

Festing, M. 1997. International human resource management strategies in multinational corporations: Theoretical assumptions and empirical evidence from German firms. Management International Review, 37 (special issue): 43–63.

Gates, S. 1996. Managing expatriates’ return. The Conference Board Europe, Inc. Research Report, Brussels.

Gerlach, M. L. 1992. Alliance capitalism. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Gong, Y. 2003. Subsidiary staffing in multinational enterprises: Agency, resources, and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 46(6): 728–739.

Grant, R. M. 1996. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17 (winter special issue): 109–122.

Gupta, A. K., & Govindarajan, V. 1991. Knowledge flows and the structure of control within multinational corporations. Academy of Management Review, 16: 768–792.

Harvey, M. G., & Richey, R. G. 2001. Global supply chain management: The selection of globally competent managers. Journal of International Management, 7(2): 105–128.

Harzing, A. W. 2001a. Of bears, bumble-bees, and spiders: The role of expatriates in controlling foreign subsidiaries. Journal of World Business, 36(4): 366–379.

Harzing, A. W. 2001b. Who’s in charge? An empirical study of executive staffing practices in foreign subsidiaries. Human Resource Management, 40(2): 139–158.

Huber, G. P. 1991. Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures. Organization Science, 2: 88–115.

Jaeger, A. M. 1983. Transfer of organizational culture overseas. Journal of International Business Studies, 14(2): 91–114.

Jaeger, A. M., & Baliga, B. R. 1985. Control systems and strategic adaptation: Lessons from the Japanese experience. Strategic Management Journal, 6(2): 115–134.

Jaussaud, J. Schaaper, J., & Zhang, Z. 2001. The control of international equity joint ventures: Distribution of capital and expatriation policies. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 6(2): 212–231.

Kennedy, P. 1998. A guide to econometrics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kobrin, S. J. 1988. Expatriate reduction and strategic control in American multinational corporations. Human Resource Management, 27(1): 63–75.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. 1993. Knowledge of the firm and the evolutionary theory of the multinational corporation. Journal of International Business Studies, 24(4): 625–645.

Levinthal, D. A., & March, J. G. 1993. The myopia of learning. Strategic Management Journal, 14 (winter special issue): 95–112.

Mezias, J. M. 2002. How to identify liabilities of foreignness and assess their effects on multinational corporations. Journal of International Management, 8(3): 265–282.

Mezias, J. M., & Scandura, T. A. 2005. A needs-driven approach to expatriate adjustment and career development: A multiple mentoring perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(5): 519–538.

Miles, R. E., & Snow, C. C. 1978. Organizational strategy, structure, and process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Miner, A. S., & Haunschild, P. R. 1995. Population level learning. Research in Organizational Behavior, 17: 115–166.

MITI (Ministry of International Trade and Industry). 2000. White paper on International Trade 2000.

Ouchi, W. G. 1979. A conceptual framework for the design of organizational control mechanisms. Management Science, 25(9): 833–848.

Paik, Y., & Sohn, J. D. 2004. Expatriate managers and MNC’s ability to control international subsidiaries: The case of Japanese MNCs. Journal of World Business, 39: 61–71.

Park, N. K., & Mezias, J. M. 2005. Before and after the technology sector crash: The effect of environmental munificence on stock market response to alliances of e-commerce firms. Strategic Management Journal, 26: 987–1007.

Peterson, R., Sargent, J., Napier, N. K., & Shim, W. S. 1996. Corporate expatriate HRM policies, internationalization, and performance in the world’s largest MNCs. Management International Review, 36(3): 215–230.

Richards, M. 2001. U.S. multinational staffing practices and implications for subsidiary performance in the U.K. and Thailand. Thunderbird International Business Review, 43(2): 225–242.

Robson, M. J., Pararoidamis, N., & Ginoglu, D. 2003. Top management staffing in international strategic alliances: A conceptual explanation of decision perspective and objective formation. International Business Review, 12(2): 173–191.

Rodgers, R. A., & Wong, J. 1996. Human factors in the transfer of the ‘Japanese best practice’ manufacturing system to Singapore. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 7(2): 455–488.

Sako, M. 1996. Suppliers’ associations in the Japanese automobile industry: Collective action for technology diffusion. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 20(6): 651–672.

Sako, M. 1999. From individual skills to organizational capability in Japan. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 15(1): 114–127.

Scullion, H. 1991. Why companies prefer to use expatriates. Personnel Management, 23(11): 32–35.

Shortell, S. M., & Zajac, E. 1990. Perceptual and archival measures of Miles and Snow’s strategic types: A comprehensive assessment of reliability and validity. Academy of Management Journal, 33: 817–832.

Simerly, R. L., & Li, M. 2000. Environmental dynamism, capital structure and performance: A theoretical integration and an empirical test. Strategic Management Journal, 21(1): 31–49.

Simonin, B. L. 1997. The importance of collaborative know-how: An empirical test of the learning organization. Academy of Management Journal, 40: 1150–1174.

Sutcliffe, K. M., & Zaheer, A. 1998. Uncertainty in the transaction environment: An empirical test. Strategic Management Journal, 19(1): 1–23.

Tan, D., & Mahoney, J. T. 2004. Explaining the utilization of managerial expatriates from the perspectives of resource-based view, agency, and transaction-costs theories. Advances in International Management, 15: 179–205.

Tarique, I., Schuler, R., & Gong, Y. 2006. A model of multinational enterprise subsidiary staffing composition. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(2): 207–224.

Tung, R. L. 1982. Selection and training procedures of U.S., European, and Japanese Multinationals. California Management Review, 25(1): 57–71.

Tung, R. L. 1984. Human resource planning in Japanese multinationals: A model for U.S. firms? Journal of International Business Studies, 15(2): 139–149.

von Hippel, E., & Tyre, M. J. 1995. How learning by doing is done: Problem identification in novel process equipment. Research Policy, 24(1): 1–12.

Wang, P., Wee, C. H., & Koh, P. H. 1998. Control mechanisms, key personnel appointment, control and performance of Sino–Singaporean joint ventures. International Business Review, 7: 351–375.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ando, N., Rhee, D. & Park, N.K. Parent country nationals or local nationals for executive positions in foreign affiliates: An empirical study of Japanese affiliates in Korea. Asia Pacific J Manage 25, 113–134 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-007-9052-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-007-9052-5