Abstract

Drawing on the structural perspective in organizational theory, this study develops a conceptual framework of the social hierarchy within the multinational corporation (MNC). We suggest that parent country nationals (PCNs), host country nationals (HCNs), and third country nationals (TCNs) occupy distinctively different positions in the social hierarchy, which are anchored in their differential control or access to various forms of capital or strategically valuable organizational resources. We further suggest that these positions affect employees’ perceptions of senior leadership opportunities, defined as the assessment of the extent to which nationality and location influence access to senior leadership opportunities. Using multilevel analysis of survey data from 2039 employees in seven MNCs, the study reveals two significant findings. First, HCNs and TCNs perceive that nationality and location influence access to senior leadership opportunities more than PCNs. Second, three moderating factors – gender, tenure, and education – increase the perception gaps between PCNs on the one hand and HCNs and TCNs on the other, although these results are inconsistent. These findings indicate that the structural position of PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs in the social hierarchy affect sense-making and perceptions of access to senior leadership opportunities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Much has been written about the effective management and the “appropriate mix” of parent country nationals (PCNs), host country nationals (HCNs), and third country nationals (TCNs) in key positions in the multinational corporation (MNC) (see Collings, Scullion, & Dowling, 2009: 1253). This literature has largely focused on strategic and economic rationales for utilizing one class of employees over another, with coordination and control, cost, knowledge, and corporate culture transfer among the main factors considered (Colakoglu, Tarique, & Caligiuri, 2009; Gaur, Delios, & Singh, 2007; Harzing, 2001). Although this classification is at the heart of the sorting process of employees into key positions across the MNC, there has been little consideration of the social meaning of these much-used labels (for a notable exception, see Caprar, 2011) and the consequent implications of the distinction between PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs for the social hierarchy of the MNC. Thus while research has pointed to a host of factors that affect global staffing decisions, it has largely overlooked the question of how these decisions on the selection for formal organizational positions are both embedded in the social hierarchy of the MNC and reproduce it by sorting PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs into “social positions that carry unequal rewards, obligations, and expectations” (Gould, 2002: 1143).

Social hierarchies are pervasive across a wide range of scales and contexts (Gould, 2002), including in complex and diverse organizations such as MNCs. They can be viewed as a mechanism – formal or informal – that differentiates between individuals and groups on the basis of various valued dimensions (Magee & Galinsky, 2008) or forms of capital (Bourdieu, 1986), thereby sorting them into more or less advantageous positions in the social structure. Furthermore, positions in the social hierarchy influence a wide variety of outcomes; the most apparent would be rewards and opportunities, but also sense-making, cognition, motivation, and behavior (Ravlin & Thomas, 2005). However, international management research has rarely conceptualized how these social structures and positions emerge, nor has it examined the influence of positions in the social hierarchy on outcomes of interest.

In this study, we seek to address these gaps in the literature first by offering a conceptual framework that deconstructs the labels of PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs, and explicates the principles that underlie their meaning and significance. Drawing on the structural perspective in organizational theory (Blau, 1977; Krackhardt, 1990; Lounsbury & Ventresca, 2003; Pfeffer, 1991) and on the work of Bourdieu (1986, 1989), we suggest these employee categories can be viewed as a summary mechanism of the distribution of power and capital within the MNC. Thus we argue that PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs occupy distinctively different positions in the social hierarchy that are anchored in their differential control or access to various forms of capital or strategically valuable organizational resources. In this respect, the attained or overall status of PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs in the MNC is rooted in the capital each possesses. This capital itself is accessible or accrued by virtue of an ascribed membership in social groups (Bourdieu, 1986).

Second, we suggest that the social hierarchy produces structural effects – the effects of the actor’s position in the social structure on outcomes (Pfeffer, 1991), including individual perceptions and attitudes (Lockett, Currie, Finn, Martin, & Waring, 2014). Hence the actor’s point of view, as the word itself suggests, is taken from a certain point or position in the social structure (Bourdieu, 1989). Specifically, we focus on how PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs perceive the influence of nationality, particularly home country nationality, and location on access to senior leadership opportunities. This outcome is particularly important because it taps into perceptions of two central mechanisms – nationality and location – that affect employees’ access to capital, which in turn affects both their position in the social hierarchy and access to career opportunities and rewards. Finally, we argue that the effect of hierarchical position on employees’ perceptions of access to senior leadership opportunities is moderated by individual capabilities.

In the following section, we discuss the configuration of the social hierarchy in MNCs and the relative position of PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs. We then develop hypotheses regarding the effect of hierarchical position on employees’ perceptions of senior leadership opportunities and the moderating effects of individual capabilities on these relations. We then present the study methodology, followed by our results. We conclude with a discussion of the findings and implications for theory and practice.

THEORY DEVELOPMENT

The concept of perceived senior leadership opportunities is defined as the assessment of the extent to which nationality and location influence access to senior leadership opportunities, particularly at the corporate level. Employees form a broad judgment concerning whether there are systematic differences in access to opportunities based on nationality and location and whether these differences are likely to persist in the future. In forming this judgment, employees draw on their observations of visible facts such as the current composition of the company’s top management and recent promotions to senior positions, as well as on their own experiences and interpretations of the role nationality and location play in structuring access to senior leadership opportunities. Thus employees evaluate, overall, who is likely to gain access to high-level career opportunities and whether these may be available for themselves and others.

Particularly germane senior leadership opportunities are promotions to positions that involve overseeing important and often global areas of the firm, including those at the very top of the organization (Perlmutter & Heenan, 1974). These encompass access to opportunities that can serve as crucial steppingstones to senior leadership positions, such as significant cross-border assignments, selection for important committees with a global mandate, and assignment to critical tasks and responsibilities with global impact (Peiperl & Jonsen, 2007). Access to career opportunities irrespective of nationality and location is an important aspect of geocentric mindset and staffing policies (Kobrin, 1994; Perlmutter, 1969) and corporate global mindset (Gupta & Govindarajan, 2002). In past studies, career opportunities in global organizations have been examined from both the standpoint of corporate policies and practices (e.g., Harzing, 2001; Kopp, 1994) and from an individual perspective (e.g., Newburry, 2001; Newburry & Thakur, 2010). Our distinctive contribution here is to examine employees’ perceptions of the often unspoken rules of the game that govern access to senior leadership opportunities, which are embedded in the company’s corporate culture and enacted international human resource management (IHRM) policies.

In explaining employees’ perceptions of access to senior leadership opportunities, we focus on the relative position of PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs in the social hierarchy of the MNC, defined as the “implicit or explicit rank order of individuals or groups with respect to a valued social dimension” (Magee & Galinsky, 2008: 354) or capital (Bourdieu, 1986).Footnote 1 Drawing on Bourdieu’s notions of the organization-as-a-field and capital, we first develop a capital-mediated model of the social hierarchy, which anchors the relative position of these three employee groups in their asymmetrical access to various forms of capital. We then explain why and how the structural position of PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs in the social hierarchy may affect their perceptions of senior leadership opportunities. Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of this study.

The Social Hierarchy in the MNC: The Organization-as-a-Field and Capital

Bourdieu defines a field as a network, or a configuration, of objective, historical relations between positions anchored in certain forms of power or capital that enable actors to operate effectively within the field (Bourdieu & Wacquant,1992). Thus the concept suggests a force field where the distribution of capital reflects and determines a hierarchical set of power relations among the competing individuals or groups (Swartz, 1997). Bourdieu (1986, 1987) distinguishes between three primary forms of capital that actors can possess. Each assumes field-specific content and value (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992). Economic capital refers to financial resources or assets that have a monetary value. Cultural capital or informational capital exists in various forms (see Lamont & Lareau, 1988), including knowledge and expertise, formal credentials, as well as longstanding behavioral and attitudinal dispositions acquired through the socialization process. Social capital is the sum of the actual and potential resources that can be mobilized through membership in social networks (Bourdieu, 1986).

According to Bourdieu, ascertaining the structure of the field involves a dual-circular task: “in order to construct the field, one must identify the forms of specific capital that operate within it, and to construct the forms of specific capital one must know the specific logic of the field” (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992: 107–108). Thus determining the structure of the MNC-as-a-field and the set of hierarchical relations among actors involves identifying three key elements: (a) the logic of the MNC or the dominant principles of hierarchy; (b) the distribution of capital, or socially valued resources; and (c) the key actors or groups that operate within the field and the kind of resources that they may possess or control (Emirbayer & Johnson, 2008) that enable them to operate effectively in the MNC and compete for social positions. Ahead we discuss each of these elements.

The dominant principles of hierarchy

We view the relationship between headquarters (HQ) and subsidiaries as the primary principle that orders the social hierarchy in the MNC. We further suggest that the centrality of home country operates as a secondary principle that shapes the social hierarchy. While these two principles intersect, we view them as conceptually distinct, each structuring the social hierarchy by influencing access to different forms of capital.

First, the relationship between HQ and subsidiaries is considered the most central dimension of the organizational structure of the MNC, as evidenced by the large body of literature that examines intra-firm relations along HQ–subsidiary lines. Furthermore, this relationship is also considered the primary axis of power relations within MNCs (e.g., Ferner, Edwards, & Tempel, 2012; Geppert & Dörrenbächer, 2014) and therefore is constitutive of the social hierarchy within MNCs. Traditionally, this relationship was viewed as strictly hierarchical; HQ was considered the center and foreign subsidiaries the periphery (see Barner-Rasmussen, Piekkari, Scott-Kennel, & Welch, 2010). Although in the past two decades alternative models of the MNC have emerged (see Andersson & Holm, 2010), Egelhoff (2010: 108) argues that still “some kind of hierarchical relationship between HQ and subsidiary is inherent in the concept of a parent HQ. While elements of an HQ can also share non-hierarchical relationships with subsidiaries, the hierarchical relationships are the defining characteristic of parent HQ.” Though the extent to which the HQ is dominant likely varies across firms, Ferner et al. (2012) argue that while subsidiaries have their own sources of influence, on balance the center has higher power over resources, processes, and meaning.

A second feature of the organizational structure that has implications for the social hierarchy is the importance of the home country. Although companies may be highly internationalized in terms of sales, production, or workforce, the home country is usually the primary locus of control, leadership, and innovation (Wilks, 2013). Members of the company board and senior management are overwhelmingly PCNs, indicating that strategic decisions are made in the home country (Hu, 1992; Jones, 2006). Thus although it has been suggested that MNCs are becoming “stateless” or footloose (e.g., Ohmae, 1990), most MNCs remain rooted in their home country (Doremus, Keller, Pauly, & Reich, 1998; Hirst & Thompson, 1999), even when equity ownership is dispersed among countries (Jones, 2006). While the centrality of the home country may vary across firms and over time, adeptness in the MNC’s home country culture, values, and language is considered more valuable relative to other cultures.

Distribution of capital

There are a number of resources that are considered valuable within MNCs, such as access or control of financial resources (economic capital), knowledge of the core or cutting-edge technology or other strategic knowledge of the MNC, deep knowledge of the home country culture and the corporate culture (cultural capital), and social connections with people of critical importance to the MNC (social capital). In general, the greater the possession of these different types of capital, the higher the place in the social hierarchy of the firm. Furthermore, these resources are unevenly distributed between key actors or groups within the MNC, influenced by the principles of hierarchy discussed previously.

Turning to the field-specific content of economic capital, HQ actors control the allocation of finance and investment through budgeting and management decisions (Ferner et al., 2012). Moreover, HQ actors also control rewards of key subsidiary actors as well as career opportunities, particularly when aspirations are international (e.g., Dörrenbächer & Geppert, 2009). The balance of cultural capital between HQ and subsidiaries also tilts in favor of HQ actors. Important for our purpose is the distinction between institutionalized cultural capital, in the form of knowledge and expertise, and tacit cultural capital, the normative and cognitive rules of the game that are embedded in the company’s corporate culture and home country culture. First, the large body of literature on cross-national knowledge transfer suggests that what HQ “brings to foreign markets is its superior knowledge, which can be utilized in its subsidiaries worldwide” (Kostova, 1999: 308; emphasis added). Subsidiary actors, for their part, are a valuable source of local knowledge and expertise (Harzing, 2001; Oddou, Osland, & Blakeney, 2008), which is often perceived to be narrower in scope and applicability. Second, HQ actors are viewed as those who embody the company’s corporate culture, identity, and value system (Kostova, 1999). Third, cultural capital rooted in a deep knowledge of the parent company’s cultural context is likely to be considered extremely valuable (Tharenou & Harvey, 2006). Finally, social capital that is generated via physical or cultural proximity to powerful actors at the HQ will be seen as more valuable than other social capital, such as links within a subsidiary, as implied by the theoretical work of Kostova and Roth (2003). Even the possession of high levels of cultural and social capital within the wider social, political, and economic environment of a subsidiary, which is crucial to success in a local market, is considered limited to that situation or context. We should emphasize that subsidiary actors also have resources at their disposal, but in the main, HQ actors possess or control a more valuable set of resources (Ferner et al., 2012; Morgan & Kristensen, 2006).

Key employee groups

The international management literature consistently differentiates among PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs (e.g., Collings et al., 2009; Harzing, 2001; Tharenou & Harvey, 2006; Thomas & Lazarova, 2013), suggesting that this classification embodies important status distinctions and enduring assumptions regarding these groups of employees. Our argument is threefold. First, these groups are constituted by their affiliation (or lack of) with HQ and the home country nationality, and the resultant asymmetrical distribution of capital among them. Second, these groups are rank ordered according to the amount of capital or strategically valuable organizational resources such as knowledge, competencies, communication capabilities, control, and trust each possesses. Third, this classification influences the allocation of positions, prestige, compensation, and other rewards. For example, global staffing decisions are often framed in terms of “employment of home, host and third country nationals to fill key positions in … headquarter and subsidiary operations” (Collings et al., 2009: 1253). Taken together, our arguments suggest that the classification of employees into PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs reflects and influences intra-firm stratification processes (Baron & Bielby, 1980) and the relative position of these employee groups in the social hierarchy of the MNC. Ahead we discuss the relative position of these groups and the influence of their positions in the social hierarchy on perceived senior leadership opportunities.

The Position of PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs in the Social Hierarchy and Perceived Senior Leadership Opportunities

In general, we suggest that PCNs occupy a higher position than HCNs and TCNs in the social hierarchy of the MNC because they possess a larger amount of capital derived from their affiliation with both the HQ and the home country. In contrast, HCNs occupy a lower position in the social hierarchy, which rests on their limited access to valuable resources and the framing of these resources as “local” or lower in “contextual range” (Ferner et al., 2012: 174). Finally, TCNs are often viewed as the “the best compromise” between PCNs and HCNs (Reiche & Harzing, 2011: 189) and therefore can tentatively be considered an intermediate status group (Caricati & Monacelli, 2010), which is structurally positioned at neither the upper nor the lower end of the social hierarchy.

Employees are likely to understand their relative position in the social hierarchy because individuals tend to be remarkably accurate in assessing their own and other people’s status and power (Smith & Galinsky, 2010; Srivastava & Anderson, 2011).Footnote 2 Furthermore, this understanding likely influences sense-making, perceptions, and behaviors in a variety of ways (see Magee & Galinsky, 2008; Ravlin & Thomas, 2005). Thus employees who occupy markedly different hierarchical positions may perceive and interpret social reality quite differently because of divergent motivations, sources of information, and immediate social and psychological environments (Tannenbaum, 2013). Accordingly, we propose that the relative position of employee groups in the social hierarchy of the MNC will influence their perceptions of senior leadership opportunities and create a significant perception gap between those who occupy a higher position in the social hierarchy and those who occupy lower positions. Our focus thus lies on examining the perception gaps between PCNs on the one hand and HCNs and TCNs on the other, which are likely to be the most pronounced.

Parent country nationals

The affiliation of parent country employees with HQ and the home country can give them access to greater business and corporate culture knowledge as well as important connections. Moreover, from an agency theory perspective, HQ can be seen as the principal whereas subsidiaries are considered agents (Brock, Shenkar, Shoham, & Siscovick, 2008; Roth & O’Donnell, 1996). Thus the level and type of assets conferred on employee groups depend largely on physical and symbolic proximity to the principal or to the central axis of power in the MNC (Oddou et al., 2008; Reiche, Kraimer, & Harzing, 2011). For example, PCNs who work at subsidiaries, such as expatriates, are symbolically proximal to the HQ and therefore “carry with them the status and influence that is associated with their role as HQ representatives. Coming from a foreign unit, inpatriates are … unlikely to encounter the same level of credibility and respect” (Reiche, 2006: 1576). In the case of PCNs, the higher status conferred by proximity to the HQ is further reinforced by proximity to the home country nationality, which affords access to cultural capital rooted in knowledge of and adeptness in the home country culture and to social capital rooted in communication and trust based on shared culture and language (Harvey, Reiche, & Moeller, 2011). Formal authority, knowledge, communication facility, and trust thus confers higher status on PCNs and gives them greater power vis-à-vis those who hold lower amounts of these assets because they enable them to affect decisions, processes, and discourse of meaning (Ferner et al., 2012; Hardy, 1996).

Due to the self-reinforcing nature of social hierarchy, the preferential access to valuable resources such as power, influence, and connections (Magee & Galinsky, 2008) may lead PCNs to develop a sense of entitlement to status, resources, and privileges. Moreover, we suggest that, compared with lower-status groups in the MNC, PCNs are less likely to recognize these privileges and acknowledge their impact on access to senior leadership opportunities for the following reasons. First, members of dominating groups may not realize that they are privileged because they do not have the social comparison information to recognize the disadvantages of subordinated groups (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). Furthermore, a higher position tends to reduce awareness of others – their perspective, knowledge, and emotions (Galinsky, Magee, Inesi, & Gruenfeld, 2006) – and therefore leads to disregard of lower-position individuals and their predicament. Second, dominant social positions are often seen as normal because they are anchored in legitimate methods of social organization. In the case of the MNC, the HQ–subsidiary hierarchy is considered a legitimate system of control and coordination, thus normalizing the position of those who are closely affiliated with this hierarchy. Relatedly, this apparent normality means that group privileges are viewed as normal (Pratto & Stewart, 2012), just like the system in which they are embedded. Third, the group identity of normalized dominant groups tends to be less salient, which allows members to deny group-based privileges. Alternatively, as Pratto and Stewart (2012: 29) put it: “dominating people less often become aware that they are privileged nor that they have social identities.” Finally, PCNs may be resistant to the idea that their status is more the product of group privileges than personal abilities because it can have adverse effects on their self-esteem. Taken together, these arguments suggest that PCNs are less likely than HCNs and TCNs to recognize that location and nationality play important roles in shaping career and promotion opportunities.

Host country nationals

HCNs probably occupy the lowest position in the social hierarchy because they are twice removed – by location and nationality – from the center of power in the MNC and are thus seen as possessing lower levels of valuable assets, such as knowledge, coordination and communication abilities, trust, and social connections. Research on subsidiary staffing decisions, for example, reveals that HCNs are viewed as less effective than PCNs when it comes to coordination and control (Boyacigiller, 1990) and knowledge management (Belderbos & Heijltjes, 2005) due to their limited experience with the firm and lack of deep knowledge of, and allegiance to, the firm’s values, culture, and strategic intent. Research on inpatriates suggests that HCNs assigned to HQ are likely to be viewed as outsiders and may be regarded as less credible or valuable sources of knowledge, and thus face challenges building interpersonal trust (Harvey, Novicevic, Buckley, & Fung, 2005; Reiche, 2011). Regarding nationality, not possessing the same nationality as the parent company is viewed as a liability due to communication and trust difficulties (Harzing, 2001; Tharenou & Harvey, 2006). We should note, however, that the value of each of these assets can be influenced by a number of internal and external variables, such as subsidiary size, importance and experience (Harzing, 2001), and HQ–subsidiary cultural (Gong, 2003; Harzing, 2001) and institutional distance (Ando & Paik, 2013; Gaur et al., 2007), and it can fluctuate over time as these variables shift or strategic direction changes (Tarique, Schuler, & Gong, 2006).

As low-ranking members in the social hierarchy, HCNs are more likely to be exposed to stereotypical expectations and experience rejection, prejudice, and stigmatization (Harvey et al., 2005) and treated as less competent, knowledgeable, and trustworthy. Thus HCNs probably know from their own experience and that of co-workers that their work location and non-parent country nationality are liabilities that affect career and promotion opportunities. Compared with PCNs, they are therefore more likely to view nationality and location as a significant barrier to senior leadership opportunities. Thus we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1a:

-

HCNs will perceive access to senior leadership opportunities to be influenced by nationality and location more than PCNs.

Third country nationals

TCNs occupy a lower position than PCNs in the social hierarchy because they have limited or no access to the resources and benefits derived from belonging to home country nationality. Specifically, TCNs may lack the same understanding of the MNC corporate and home country cultures as PCNs and therefore may be less effective, for example, in linking HQ and subsidiaries (Gaur et al., 2007). Furthermore, their status can also be influenced by transaction costs, which increase when an employee is a non-home country national, leading to lower communication efficiency and trust due to higher cultural distance and more limited knowledge of HQ goals and culture (Harzing, 2001; Tharenou & Harvey, 2006). This may also hamper their ability to develop important social connections with PCNs.

Furthermore, as a minority group within the MNC, TCNs may experience exclusion and unjust treatment, although this may be affected by whether or not they were socialized at the parent country HQ (Tarique et al., 2006). Daniels (1974: 29–30), for example, found that TCNs working for American MNCs perceive that “they are effectively excluded from the so-called better jobs because preference is given to Americans.” These perceptions stood in “marked contrast to the opinion of the [American] decision makers who view the nationality mix to be a result of national differences in mobility and qualifications” (Daniels, 1974: 30). This evidence, along with the lower status of TCNs, leads us to expect that compared with PCNs, TCNs are also more likely to recognize the impact of nationality and location on access to senior leadership opportunities. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1b:

-

TCNs will perceive access to senior leadership opportunities to be influenced by nationality and location more than PCNs.

Moderating Influences

Thus far, we have considered a structural perspective on social hierarchies, suggesting that the relative status of individuals is related to the capital each accrues through ascribed membership in social groups, independent from their individual qualities. If looked at from an individualistic perspective, however, the relative status of individuals is attributed to underlying variations in individual capabilities or human capital (Becker, 1964). We explore a blended approach in this section, one in which individual capabilities interact with an ascribed structural position to affect access to capital or valuable organizational resources and ultimately the relative status of individuals in the social hierarchy. Thus we argue that individual capabilities moderate the effect of employees’ structural position on perceived senior leadership opportunities because they alter their relative status, expectations, and experiences at the workplace. We further suggest that individual characteristics moderate this effect through homogenization and social comparison processes.

Specifically, we examine the moderating influence of four individual capabilities – managerial status, tenure, education, and intercultural competencies – because these capabilities are the key to unlocking access to the three forms of capital underpinning the social hierarchy in the MNC. Managerial status and tenure reflect firm-specific human capital and capabilities (Hitt, Bierman, Shimizu, & Kochhar, 2001) that can be particularly conducive to accumulating intra-firm economic, cultural, and social capital (Lin & Huang, 2005). High levels of education and intercultural competencies are associated with both general and firm-specific human capital and can enhance the accumulation of valuable social and cultural capital within and outside the MNC. Although not a capability, we also consider the moderating influence of gender because previous research has shown that it can affect access to economic and social capital within the firm (Ibarra, 1992).

Managerial status

From a structural perspective, parent country managers are affiliated with two high-status groups – the managerial echelon of the MNC and the PCN group. As suggested earlier, membership in a high-status group can blind group members to the privileges they enjoy, particularly because they are less likely to engage in social comparison with subordinate groups and have less relevant social comparison information (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). By extension, membership in two high-status groups can be especially blinding. Furthermore, because parent country managers would like to maintain a positive self-image and take credit for their own managerial status, they may be less inclined to recognize that group-based privileges could have contributed to their managerial status. Thus in the case of parent country managers, the dual high-status position is likely to strengthen the association between their employee category and perceived senior leadership opportunities.

Host and third country managers also have an affiliation with the managerial echelon of the MNC. They are also likely to have higher levels of intra-firm social and cultural capital (Lin & Huang, 2005) compared with non-managerial host and third country employees. These enable them to align themselves with the managerial echelon as a status enhancement strategy (Ellemers, 1993) – an option particularly available to very senior host and third country executives (Zhang, George, & Chan, 2006). However, they are also affiliated with the lower-status groups of HCNs and TCNs and therefore more likely to receive lower returns on their accumulated expertise than parent country managers (Friedman & Krackhardt, 1997). They are also likely to have more social comparison information than non-managerial host and third country employees and compare themselves with other managers, especially with parent country managers and expatriates. As a result, they may become aware of any preferential treatment received by PCNs and experience feelings of relative deprivation and unfair treatment (Toh & DeNisi, 2003).

In summary, evidence suggests that due to their high status in the social hierarchy, parent country managers are more likely to under-recognize the significance of nationality and location in promotion to senior managerial positions. Host and third country managers, on the other hand, are more likely to be more fully aware of these barriers. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is constructed as follows:

Hypothesis 2a:

-

Differences between PCNs and HCNs in the perceived influence of nationality and location on access to senior leadership opportunities will be larger for managers than non-managers.

Hypothesis 2b:

-

Differences between PCNs and TCNs in the perceived influence of nationality and location on access to senior leadership opportunities will be larger for managers than non-managers.

Organizational tenure

Organizational tenure, defined as the length of employment in an organization (McEnrue, 1988), has important direct and moderating effects on a wide range of employee attitudes and behaviors (Ng & Feldman, 2010; Ng & Feldman, 2011). As organizational tenure accumulates, employees are increasingly socialized into the organization and are more influenced by the organization’s culture, norms, and goals (Chatman, 1991; Rollag, 2004). Furthermore, selection and socialization processes associated with longer organizational tenure lead to an increasingly homogenous workforce because employees who do not fit within the organization are selected out or leave of their own accord (Schneider, 1987). Thus longer organizational tenure can promote more homogeneous views among employees and consequently weaken the association between hierarchical position and perceived senior leadership opportunities.

Longer organizational tenure may have a distinct effect on HCNs and TCNs via firm-specific human, cultural, and social capital. Host and third country employees with longer tenure have more firm-specific human and cultural capital than those with shorter tenure, and they are arguably more valuable to the organization. They may also have more organizational experience and insider knowledge of how the organization works and therefore be better able to maneuver within the organization (Sturman, 2003). Longer organizational tenure also fosters the development of firm-specific social capital – a set of relationships both within the organization and with external stakeholders. All these factors may help HCNs and TCNs overcome career barriers associated with work location and nationality, and therefore may affect their perceptions of senior leadership opportunities.

In summary, evidence suggests that organizational tenure may diminish the effects of hierarchical position associated with employee categories on perceived senior leadership opportunities by increasing the salience of common organizational culture and goals and fostering organizational-specific knowledge and relationships that may prevail over structural divides. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3a:

-

Differences between PCNs and HCNs in the perceived influence of nationality and location on access to senior leadership opportunities will be smaller for those with longer organizational tenures than those with shorter organizational tenure.

Hypothesis 3b:

-

Differences between PCNs and TCNs in the perceived influence of nationality and location on access to senior leadership opportunities will be smaller for those with longer organizational tenures than those with shorter organizational tenure.

Education

A higher level of education is likely to diminish the association between hierarchical position and perceived senior leadership opportunities for the following reasons. First, highly educated workers often exhibit similar attitudes and behaviors, such as contributing more effectively to both core and non-core task performance, and display greater creativity and more citizenship behaviors (Ng & Feldman, 2009). These similarities can potentially narrow the perception gap among highly educated employees. Second, highly educated PCNs are more likely to recognize the effects of work location and nationality on career and promotion opportunities because higher education promotes awareness of discrimination against minorities, greater tolerance and support for social integration, and lower levels of in-group bias and prejudice (Coenders & Scheepers, 2003; Wodtke, 2012). Finally, highly educated HCNs and TCNs are more likely to be considered a valuable asset to the organization because they have higher cultural capital such as knowledge and expertise. This may allow them to overcome career barriers associated with their employment category, which, in turn, can affect their perceptions of career opportunities within the MNC.

Taken together, the previous discussion suggests that higher levels of education may diminish the influence of hierarchical position on perceived senior leadership opportunities through the promotion of a common worldview among highly educated employees, awareness of discrimination on the part of PCNs, and accumulation of valuable capital by HCNs and TCNs. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 4a:

-

Differences between PCNs and HCNs in the perceived influence of nationality and location on access to senior leadership opportunities will be smaller for those with higher education than those with less education.

Hypothesis 4b:

-

Differences between PCNs and TCNs in the perceived influence of nationality and location on access to senior leadership opportunities will be smaller for those with higher education than those with less education.

Intercultural competencies

Intercultural competencies, broadly defined as the ability to interact effectively with people from other cultures (Spitzberg & Changnon, 2009), may also moderate the relationship between hierarchical position and perceived senior leadership opportunities. While there are multiple approaches to defining intercultural competencies, Johnson, Lenartowicz, and Apud (2006) suggest that intercultural competence requires or implies three factors: attitude, skills, and knowledge. These factors suggest multiple competencies and sensibilities (Newburry, Belkin, & Ansari, 2008) that may affect the ways in which PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs perceive senior leadership opportunities. First, intercultural communication skills are a fundamental capability in a complex cultural context. The ability to speak multiple languages can be considered a generalized communication skill that contributes to a sense of ease and efficacy in intercultural settings (Thomas & Osland, 2004), which enhances intercultural communication. Similarly, intensive cultural experiences through foreign living experience and studying abroad can also foster the development of intercultural competencies through experiential learning (Ng, Van Dyne, & Ang, 2009).

Second, intercultural competencies involve sensitivity to and awareness of the emotions and feelings of others (LaFromboise, Coleman, & Gerton, 1993), which can then lead to empathy – the ability to take perspective or shift frame of reference vis-à-vis people from other cultures (Hammer, Bennett, & Wiseman, 2003). Thus for PCNs, intercultural competencies may foster awareness of the career barriers faced by HCNs and TCNs due to their outsider status in the MNCs. Furthermore, culturally competent PCNs may also form more professional and social ties with HCNs and TCNs and thus learn through these ties about the impact of nationality and location on access to senior leadership opportunities.

Third, culturally competent HCNs and TCNs may be considered more valuable to the organization because of their abilities to work effectively in different cultural and institutional environments. Moreover, these skills may enable them to span organizational boundaries (Kostova & Roth, 2003) and build cross-border social networks (Levy, Peiperl, & Bouquet, 2013) that can decrease barriers to internal career mobility and advancement, thus affecting their perception of access to senior leadership opportunities. This may be particularly important to TCNs who work on a daily basis with people from other cultures.

In sum, intercultural competencies may diminish the association between hierarchical position and perceived senior leadership opportunities by contributing to PCNs awareness and by facilitating the career mobility of HCNs and TCNs within the MNC. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 5a:

-

Differences between PCNs and HCNs in the perceived influence of nationality and location on access to senior leadership opportunities will be smaller for those with higher intercultural competence than those with lower intercultural competence.

Hypothesis 5b:

-

Differences between PCNs and TCNs in the perceived influence of nationality and location on access to senior leadership opportunities will be smaller for those with higher intercultural competence than those with lower intercultural competence.

Gender

The relationship between hierarchical position and perceived senior leadership opportunities should be stronger for men than women for a number of reasons. First, parent country male employees belong to two high-status groups (i.e., male and PCNs) and usually constitute the dominant group within the MNC, enjoying higher status, more promotion opportunities, and higher salaries than most other employees. This dual high-status position may lead parent country male employees to under-recognize the importance of nationality and location in constituting their privileged position in the organization. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that acknowledging their male privilege or those unearned advantages may threaten men’s self-esteem and have an adverse effect on their confidence and satisfaction (Rosette & Thompson, 2005). Parent country female employees, by contrast, have fewer unearned privileges to protect and are therefore less motivated to understate the significance of nationality and location within the MNC.

Turning to host and third country male employees, we expect that they would perceive nationality and location as more important forces in shaping opportunities within the MNC than either parent country men or women for several reasons. First, although in the broader societal context, host and third country men generally belong to a high-status group (i.e., male), they are accorded a lower or more peripheral status within the MNC due to their nationality and work location. Hence they may experience a status imbalance and feel that their societal status is threatened and eroded at work. Previous research has suggested that when male privilege is threatened, men tend to overstate the severity of the threat and overreact to it (Schmitt, Branscombe, Kobrynowicz, & Owen, 2002). Second, men tend to accumulate task-oriented social capital through instrumental ties developed in the course of work role performance, which can then be used to achieve valued career outcomes (Ibarra, 1992). However, host and third country male employees may receive lower than expected returns on their social capital due to their lower status in the social hierarchy. Third, men tend to define themselves in terms of workplace status and performance more than women do. Therefore perceived exclusion and unfair treatment in the workplace threaten men’s self-esteem and confidence and they tend to react more negatively than women (Hitlan, Cliffton, & DeSoto, 2006). Furthermore, when men perceive an exchange relationship to be inequitable, they also react more negatively than women do (Brockner & Adsit, 1986).

In summary, evidence suggests that men’s perceptions are likely to be polarized along hierarchical lines: Host and third country male employees are more likely to view nationality and location as significant career barriers, whereas parent country male employees are less likely to acknowledge the effect of these barriers. We expect women’s perceptions, compared with men’s, to be less divided along hierarchical lines. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 6a:

-

Differences between PCNs and HCNs in the perceived influence of nationality and location on access to senior leadership opportunities will be larger for men than women.

Hypothesis 6b:

-

Differences between PCNs and TCNs in the perceived influence of nationality and location on access to senior leadership opportunities will be larger for men than women.

METHODOLOGY

The data for this study were collected in seven publically traded MNCs – three headquartered in Australia, two in Japan, and two in the United States. These MNCs represent five industries: Telecommunications, high-technology manufacturing, chemical, banking and financial services, and other services. Their worldwide staff ranges from 9774 to 157,966. In each company, we surveyed employees in both the corporate head offices and at least two wholly owned overseas subsidiaries – a total of 30 locations. The 23 participating overseas subsidiaries were located in Brazil, Japan, the Philippines, Spain, Switzerland, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Procedure

The data used in our analysis come from a paper-and-pencil questionnaire survey distributed to employees in both the company HQ and overseas affiliates of each firm. The original English-language questionnaire was translated into German, Japanese, Portuguese, and Spanish by professional translators and then back-translated and checked for idiomatic equivalency to the English original. In addition, native-speaking employees at participating companies read the translations for accuracy and comprehension. We used native language questionnaires in all locations, except the Philippines and Thailand where questionnaires were distributed in English as English was the common language used within the affiliates and all respondents spoke and read English. In other subsidiary locations, the questionnaire was provided in both the local language and the parent country language (i.e., English or Japanese).

In all locations, the questionnaires along with self-seal envelopes for the completed questionnaires were distributed by the local human resources department and were returned to the department, which sent them on for central processing. Respondents were invited in a letter to participate in a research project conducted by a reputable business school in the United States. They were assured that their responses would be processed by an independent survey firm and would be kept anonymous and confidential. Participation was strictly voluntary and no monitoring of respondents took place at any stage of the questionnaire completion.

Participants

The sample consisted of 2039 employees working in 30 locations. In total, 826 (40.5%) of the sample participants were employed by Australian, 733 (35.9%) by American, and 480 (23.5%) by Japanese MNCs. The sample included 616 (31.1%) PCNs, 1152 (56.6%) HCNs, and 271 (13.3%) TCNs. Of the PCNs, 315 (51.1%) were Australian, 205 (33.3%) American, 96 (15.6%) Japanese, and 91% of them worked at corporate HQ. Of the HCNs, 510 (44.1%) were American, 169 (14.7%) Japanese, 149 (12.9%) Brazilian, and 104 (9%) Filipino. The majority (70%) of TCNs worked at overseas subsidiaries. TCNs came from 56 countries; respondents from the United Kingdom (21.1%), Germany (10.3%), the Netherlands (8.5%), New Zealand (7%), and China (5.2%) accounted for just over 50% of TCNs. Table 1 presents demographic characteristics across the three employee groups.

Measures

Dependent variable

Perceived senior leadership opportunities was measured using a scale that assesses the extent to which nationality, particularly home country nationality, and location are perceived as influencing access to senior leadership opportunities within the MNC (Kobrin, 1994). Respondents were asked to indicate agreement/disagreement on a 7-point Likert scale with the following five statements:

In this company as a whole:

-

1)

A manager who began his or her career in any country has an equal chance to become CEO of this company.

-

2)

In the next decade, I expect to see a non-American (Australian/Japanese) CEO of this company.

-

3)

In the next decade, I expect to see one or more non-American (Australian/Japanese) nationals serving as a senior corporate officer on a routine basis.

-

4)

In my company, nationality is unimportant in selecting individuals for managerial positions.

-

5)

My company believes that it is important that the majority of top corporate officers remain American (Australian/Japanese) (reverse coded).

Principal Component Factor Analysis extracted one unambiguous factor with a single large eigenvalue, a high explained variance, and Cronbach’s α of 0.80. Multilevel Confirmatory Factor Analysis with robust standard errors was conducted to test the hypothesis that a single-factor underlies responses to these five items. The clustering variable was location to account for the nesting of participants within office locations. A single-factor with uncorrelated residuals was specified at the within- and between-location model levels; this model did not fit the data well, χ2 (10)=249.91, p<0.001, CFI=0.84, RMSEA=0.101, SRMR(between)=0.055, SRMR(within)=0.071. Inspection of model modification indices indicated that permitting a covariance between the item 2 and 3 residuals would improve model fit. As these items share a common time referent (i.e., in the next decade), permitting this correlation as a methods effect was deemed reasonable. The modified model fit reasonably well, χ2 (8)=78.38, p<0.001, CFI=0.95, RMSEA=0.061, SRMR(between)=0.036, SRMR(within)=0.027.

Another measurement concern is the issue of measurement equivalence/invariance given the multilingual and multinational sample. The minimum requirement for comparing groups on a measure is “weak measurement invariance” where item factor loadings are invariant across groups. Two sets of analyses were conducted to explore this issue. In each set, a series of multiple-groups Confirmatory Factor Analysis models that account for the clustering of participants in locations were fit to the data. In the first set, factor loadings were tested for equality across groups where the groups were defined by the five questionnaire languages (i.e., English, Japanese, Portuguese, German, and Spanish). The model constraining factor loading equality across these survey languages did not fit significantly worse than the model without these constraints, Δχ2(20)=23.69, p=0.25. In the second set, we focused on the subset and majority (73%) of participants who completed the survey in English where the groups were defined by whether the participant indicated English as a native language or not. The model constraining factor loading equality across groups did not fit significantly worse than the model without these constraints, Δχ2(5)=4.40, p=0.49. Thus, we cautiously conclude that there are not significant measurement differences that would preclude comparisons of scores across survey languages and across native and non-native English speakers.

Independent variables

Employee categories were coded as two dichotomous variables: HCNs were coded as 1, otherwise 0; TCNs were coded as 1, otherwise 0. The reference group was PCNs. A respondent was coded as HCN if he or she worked at an overseas subsidiary and was originally from the host country; a respondent was coded as TCN if he or she worked either at the corporate HQ and was not originally from the company parent country or worked at an overseas subsidiary and was not originally from the host country nor the company parent country. A respondent was coded as PCN if he or she worked at the corporate HQ or at an overseas subsidiary and was originally from the parent company country.

Respondent demographic variables were self-reported. Managerial status was coded as 1 for managers, otherwise 0. Gender was coded 1 for male and 0 for female. Organizational tenure was measured as number of years that the employee had worked in the MNC. Education is categorical, coded 1 if less than high school and ranging to 6 for completed graduate school.Footnote 3

Intercultural competencies were measured with a formative index that included three items theoretically related to individual competencies to handle the demands of a global work environment (Newburry et al., 2008): the number of foreign languages spoken (coded: None=0; one foreign language=1; two or more=2), living abroad for more than 1 year (other than for education; coded: No=0; Yes=2); and 1 or more year of formal education abroad (coded: No=0; Yes=2). This method of coding gave equal weight to each item as simple weighting formulas often outperform complex weighting formulas (Dawes, 1979). The intercultural competencies measure is based on the sum of the three item scores with a theoretical range of 0–6. Correlations among item responses ranged from 0.22 to 0.45 and a principal components analysis indicated one eigenvalue greater than 1. The logic of this measure as discussed in Newburry et al. (2008) suggests that this measure of intercultural competencies is a formative rather than a reflective measure. Therefore we do not report reliability tests because the use of reliability indices with formative measures has been questioned (Jarvis, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, 2003). An empirical analysis of the formative structure of the measure of intercultural competencies is available from the first author.

Controls and Analytic Approach

The five individual-level variables discussed previously were included as controls in our interpreted statistical models. We also included two additional individual-level control variables. To account for the possibility that employees’ perceptions may be affected by company information, we included an item that asked respondents to indicate whether they received training or briefings on the parent company’s history, management philosophy, and/or vision (coded: No=0; Yes=1). We also included as a control a 5-item scale that measured employees’ perceptions of the human resource practices common to the business unit where they worked based on the high-performance work practices literature (e.g., Delery & Doty, 1996; Huselid, 1995). Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.77. We used firm’s parent country dummy variables to control for variance attributable to broad country-of-origin factors. Japan parentage was treated as the reference category and dummy variables were created for the Australian and the US firms. The descriptive statistics for all study variables are shown in Table 2.

Research has emphasized the need to attend to nested data structures that account for the clustering of participants within locations and firms (Peterson, Arregle, & Martin, 2012). Therefore we conducted multilevel analyses to account for the hierarchical structure of our data (Snijders & Bosker, 1999) using a series of mixed-effects (i.e., multilevel) models that account for the clustering of participants within the thirty work locations and the seven firms. Because we were interested in comparing nested models for fit, we used maximum likelihood estimation rather than the typical software default of restricted maximum likelihood estimation. These models begin with no predictors to assess the degree of clustering in perceived senior leadership opportunities scores across the work locations and firms. In the next two models, we add the two firm-level country-of-origin control variables followed by a set of individual-level control variables. In Model 4, we add our employee categories of PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs to the model to test Hypotheses 1a and 1b. Finally, we add the hypothesized interactions of these employee categories with individual demographic characteristics individually in Models 5a–e and all together in Model 5. The estimated parameters of these models are presented in Table 3 for the included predictor and control variables. Table 4 presents the results of tests comparing adjacent models. We centered all variables involved in the hypothesized interactions prior to analysis (except the dichotomous variables – gender and managerial status) to improve the interpretation of the model parameters.

RESULTS

The results of Model 1 in Table 3 indicate that there is significant variance in predicted perceived senior leadership opportunities scores across locations but not across firms when location differences are accounted for. Nonetheless, Model 2 which adds the two firm-level country-of-origin control variables fits significantly better than Model 1 (χ2(2)=9.02, p=0.01) as displayed in Table 4 and accounts for nearly all of the firm-level random effect variance (Δ pseudo-R2>0.99). Similarly, Model 3 which adds the participant-level control variables to the model fits better than Model 2 (χ2(7)=2149.24, p<0.001) and explains additional participant-level and location-level variance (Δ pseudo-R2s of =0.13 and 0.21, respectively). Furthermore, Model 4, which adds the employee classification variables (PCN, HCN, and TCN) to the model, fits better than Model 3 (χ2(2)=260.09, p<0.001) and explains some additional participant-level and location-level variance (Δ pseudo-R2s of<0.01 and =0.08, respectively). Note that in our coding scheme for all models, PCNs are the reference category.

In Hypotheses 1a and 1b, we predicted that HCNs and TCNs will perceive access to senior leadership opportunities to be influenced by nationality and location more than PCNs, respectively. In Model 4, the coefficients in Table 3 indicate that, relative to PCNs, HCNs (γ=−0.47, t(401.81)=−4.26, p<0.001) and TCNs (γ=−0.34, t(1647.66)=−3.10, p=0.002) have significantly lower perceived senior leadership opportunities scores when controlling for the other variables in the model, thus supporting Hypotheses 1a and 1b.

We next turn to the interactive effects of employee categories and participant characteristics specified in Hypotheses 2 through 6. Indeed, with all hypothesized interactions added to the model simultaneously, Model 5 fit the data better than Model 4 (χ2(10)=22.28, p=0.01, Δ pseudo-R2s of =0.01 and =0.06 for participant- and location-level variance reduction, respectively) and many of the individual interaction coefficients are statistically significant as displayed in Table 3. Because the employee category variables (i.e., PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs) appear in each of these interactions and this can reduce statistical power as these interactions are correlated and may account for common variance, we next tested each interaction hypothesis separately in Models 5a through 5e.Footnote 4

In Hypotheses 2a and 2b, we predicted that differences in perceived senior leadership opportunities between PCNs and HCNs and between PCNs and TCNs, respectively, would be larger for managers than non-managers. However, Model 5a, which permitted these interactions, did not fit significantly better than Model 4 (χ2(2)=1.71, p=0.43, Δ pseudo-R2s of =0.001 and =0.01 for participant- and location-level variance reduction, respectively). Thus, Hypotheses 2a and 2b were not supported.

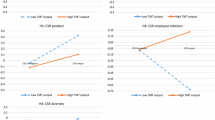

In Hypotheses 3a and 3b, we predicted that differences in perceived senior leadership opportunities between PCNs and HCNs and between PCNs and TCNs, respectively, would be smaller for those with longer organizational tenures than those with shorter organizational tenures. Model 5b, which permitted these interactions, fit significantly better than Model 4 (χ2(2)=7.02, p=0.03, Δ pseudo-R2s of =0.002 and =0.08 for participant- and location-level variance reduction, respectively). Contrary to Hypothesis 3a and as displayed in Figure 2a, the interaction coefficients in Table 3 for Model 5b indicate that the difference in scores between PCNs and HCNs (γ=−0.02, t(1996.54)=−2.66, p=0.008) were significantly larger for those with longer than shorter organizational tenures. Hypothesis 3b was not supported as the difference in scores between PCNs and TCNs (γ=−0.01, t(2008.76)=−1.09, p=0.28) were not statistically different for those with longer than shorter organizational tenures. Note that in this figure we define low and high tenure as being 1 standard deviation below and above the mean tenure, respectively. Thus, Hypotheses 3a and 3b were not supported.

(a) Interactive effects of employee category, tenure, and perceived senior leadership opportunities.(b) Interactive effects of employee category, education, and perceived senior leadership opportunities.(c) Interactive effects of employee category, gender, and perceived senior leadership opportunities.

In Hypotheses 4a and 4b, we predicted that differences in perceived senior leadership opportunities between PCNs and HCNs and between PCNs and TCNs, respectively, would be smaller for those with more education than those with less education. Model 5c, which permitted these interactions, fit significantly better than Model 4 (χ2(2)=7.74, p=0.02, Δ pseudo-R2s of =0.004 and =0.003 for participant- and location-level variance reduction, respectively). Hypothesis 4a was not supported as the difference in scores between PCNs and HCNs (γ=−0.04, t(2000.31)=−1.03, p=0.31) did not differ significantly for those with more education than less. Contrary to Hypothesis 4b and as displayed in Figure 2b, the interaction coefficient in Table 3 for Model 5c indicates that the difference in scores between PCNs and TCNs (γ=−0.15, t(1994.20)=−2.78, p=0.006) were significantly larger for those with more education than less. Note that in this figure we define low and high education as being 1 standard deviation below and above the mean education level, respectively. Thus, Hypotheses 4a and 4b were not supported.

In Hypotheses 5a and 5b, we predicted that differences in perceived senior leadership opportunities between PCNs and HCNs and between PCNs and TCNs, respectively, would be smaller for those with higher than lower intercultural competence. However, Model 5d, which permitted these interactions, did not fit significantly better than Model 4 (χ2(2)=3.54, p=0.17, Δ pseudo-R2s of =0.002 and <0.001 for participant- and location-level variance reduction, respectively). Thus, Hypotheses 5a and 5b were not supported.

In Hypotheses 6a and 6b, we predicted that differences in perceived senior leadership opportunities between PCNs and HCNs and between PCNs and TCNs, respectively, would be larger for men than women. Model 5e, which permitted these interactions, fit significantly better than Model 4 (Δ2(2)=7.63, p=0.02, Δ pseudo-R2s of =0.004 and =0.003 for participant- and location-level variance reduction, respectively). As displayed in Figure 2c, the interaction coefficients in Table 3 for Model 5e indicate that the difference in scores between PCNs and HCNs (Δ=−0.30, t(2001.37)=−2.44, p=0.015) and between PCNs and TCNs (Δ=−0.41, t(1997.21)=−2.30, p=0.02) were larger for men than women. Thus, Hypotheses 6a and 6b were supported.

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest there are significant perception gaps between PCNs and HCNs and between PCNs and TNCs. Additionally, these perception gaps increase with three moderating factors: gender, tenure, and education. Examining our direct effect hypotheses first, we find that HCNs and TCNs perceive access to senior leadership opportunities to be influenced by nationality and location more than PCNs. Thus employees’ sense-making and perceptions diverge along hierarchical lines where those who occupy a high position is the social hierarchy under-recognize the systematic differences in access to opportunities. These findings are consistent with research on perception gaps along gender and racial divides, which are relatively more stable and enduring. Gender studies, for example, consistently show that perceived discrimination against women is higher among women than among men (e.g., Gutek, Cohen, & Tsui, 1996). We should note, however, that whereas the effect of hierarchical positions in the MNC may mimic the effect of more stable status markers, this does not necessarily reflect essential differences between organizational members, because status hierarchies can arise even in cases where there is a lack of obvious differentiation among members (Ravlin & Thomas, 2005).

Our analyses of the impact of demographic moderators yield some unexpected results. Our initial expectations were that the increased access to capital typically associated with longer tenure, higher education, and high intercultural competencies would enhance the relative status of HCNs and TCNs in the social hierarchy and consequently diminish the effect of their structural position on perceptions. However, we find no support for these hypotheses. In those instances where significant interactions were found, they were opposite to our predictions. These results suggest that the established social hierarchy has such a powerful effect that high levels of individual capital endowment fail to override it. Furthermore, the effect of the social hierarchy further intensifies among highly qualified individuals, thereby driving the perceptions of PCNs on the one hand and HCNs and TCNs on the other further apart.

Examining our specific demographic moderators, the tenure result indicates that more time in the organization heightens the effect of the social hierarchy rather than diminishes it. In particular, HCNs with longer organizational tenure view nationality and location as more important in structuring access to senior leadership opportunities than PCNs with a comparable level of tenure. TCNs exhibited a similar pattern, but this result did not reach statistical significance. One explanation is that longer tenure is associated with higher levels of firm-specific social and cultural capital, which can lead to higher expectations regarding access to organizational opportunities. At the same time, longer tenure is also associated with more information about the rules governing access to organizational opportunities and direct experience with the organization’s procedural and distributive justice system (Ambrose & Cropanzano, 2003). Thus contrary to the view that tenure acts as a homogenizing force in organizations (e.g., Schneider, 1987), our finding suggests that the accumulation of negative experiences and information about systematic differences in access to opportunities, actually results in divergent views.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we find that higher levels of education strengthen the negative association between employee categories and perceived senior leadership opportunities among TCNs. A similar pattern was found among highly educated HCNs, but this result was not significant. Thus we find that highly educated TCNs are more keenly aware of career barriers and discriminatory practices, possibly due to their higher expectations from accumulated firm-specific social and cultural capital. While the literature suggests that highly educated PCNs should share this awareness of barriers, our finding does not support that. A possible explanation may be that although higher education increases awareness of inequality, it can also promote its reproduction by propagating among those in higher positions of power: “the idea that inequality is meritocratic, i.e., it results from individual differences in talent, effort, and education credentials rather than from discrimination on the basis of ascribed group characteristics” (Davis & Robinson, 1991: 73). Thus the impact of higher education appears to be complex; it heightens awareness of discriminatory practices and at the same time legitimizes inequality because it provides a meritocratic rationale for its reproduction (Kane & Kyyrö, 2001).

The gender results indicate that men’s perceptions of senior leadership opportunities are polarized along hierarchical lines. Of all the subgroups, the perception gap is the largest between parent and host country male employees, suggesting that these two subgroups occupy diametrically opposed structural positions, very possibly because they see themselves in direct competition for resources and positions. The perceptions of women, by contrast, are less polarized. In particular, parent country female employees seem to be more sensitive to exclusionary practices than their male counterparts. Additionally, host and third country female employees view the MNC environment more favorably than their male counterparts. These findings contribute to the ongoing debate about the role of women in international business. For host and third country women, the “female advantage” (Helgeson, 1990) of women who work in an international environment (Guthrie, Ash, & Stevens, 2003; Haslberger, 2010) may translate into a more positive work experience in MNCs, which in turn may affect their perceptions. One alternative explanation is that host and third country female employees have lower expectations about inclusion or mobility in global firms, and hence they are less concerned with global career opportunities. Another is that their primary concern is gender-based discrimination and therefore nationality or location-based discrimination is less salient. These are potentially rich avenues for further study.

Limitations

There are, of course, several limitations to this study that we should acknowledge. First, although this study examined the perceptions of a large number of employees across both corporate HQ and multiple overseas subsidiaries, it included only seven MNCs. In order to verify the generalizability of the results, a larger sample of MNCs, headquartered in diverse countries, particularly emerging economies such as China, India, and Brazil, would be necessary to account for variations in country-level variables such as economic development, institutional background, and degree of economic connectedness of both the MNC’s home country and subsidiary countries. Furthermore, variations in firm-level variables, such as HQ dominance and home country centrality can also affect the results. Recognizing these issues, we took several actions to minimize the effect of these sources of variation in the data.

Second, we should also acknowledge that the practical magnitude of our results (i.e., Δ pseudo-R2s) is small and their statistical significance may reflect a large overall sample size. However, we note that small effects can be important, particularly when testing theories and when small effects are translated onto a global scale (Prentice & Miller, 1992).

Third, this study did not directly measure the actual inclusion of non-PCNs in each firm. Rather, we focused on perceived access to senior leadership opportunities. While we believe that assessing employees’ perceptions is the best way to gauge how employees feel about their organization, future research should study the gap between actual and perceived career opportunities, and consider their combined effect on the social hierarchy and on employees.

Finally, although we examined five important individual characteristics as critical moderators of the relationships between structural position and perceived senior leadership opportunities, this framework is by no means comprehensive. Future research could certainly test hypotheses about other possible moderating influences that are beyond the scope of this study.

Implications for Theory

In this study, we offer a theoretical framework for the social hierarchy within the MNC and suggest that PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs occupy distinctively different positions in the social hierarchy, which are anchored in their differential control or access to various forms of capital. We further suggest that these positions affect sense-making and perceptions and are likely to influence a number of other behaviors. This approach has three major implications for theory.

First, we adopt a multidisciplinary approach that synthesizes across diverse literatures in sociology and organizational theory, and provides a conceptual framework that draws attention to the social construction of employee categories and to the non-rational and non-economic reasons that shape the intra-firm stratification process (Baron & Bielby, 1980). Despite the considerable amount of research on intra-firm cross-border mobility and global staffing decisions, there have been few attempts to understand how these processes are embedded in, and perhaps at times overshadowed by, the social hierarchy of the MNC. In this study, we conceptualize the social and political underpinnings of the capital-mediated process that sorts different groups of employees into advantageous/disadvantageous positions in the social structure. Thus we suggest that although relative standing of employees who belong to the parent, host, and third country categories is anchored in capital and therefore presumably reflects some underlying variations in individual qualities, access to capital is often a function of an ascribed membership in social groups and beyond the control of the individuals and unrelated to their abilities (Ravlin & Thomas, 2005).

The second major contribution of our study is to demonstrate that the structural positions of PCNs, HCNs, and TCNs affect their perceptions. These results extend insights from previous research on perceived career opportunities (e.g., Murtha, Lenway, & Bagozzi, 1998; Newburry, 2001; Newburry & Thakur, 2010) and perception gaps within the MNC (e.g., Asakawa, 2001; Birkinshaw, Holm, Thilenius, & Arvidsson, 2000). This notion complements the predominant view that perception gaps are driven principally by imperfect flows of information, cognitive and attribution biases, and location characteristics. In particular, our findings point to some important issues in the dynamics of the MNC as a contested social space where HQ and subsidiary actors engage in micro-political conflicts (Morgan & Kristensen, 2006). Whereas previous research has focused on realistic conflicts over resources (e.g., Dörrenbächer & Gammelgaard, 2011), we highlight the clash between competing constructions of the social reality. Thus the study of micro-politics in HQ–subsidiary relations must include an account of how actors’ positions in the social structure both enables and constrains their perceptions, often leading to different or even antagonistic points of view (Bourdieu, 1989).

Finally, our framework has implications for the study of culture in MNCs. International management research has been dominated by essentialist analyses of national cultures and cultural differences (Vaara, Tienari, & Säntti, 2003). The concept of cultural capital, on the other hand, focuses on culture as a resource used in the reproduction of power relationships and symbolic boundaries between employee groups in the MNC. This view shifts attention from the core dimensions of culture (i.e., cultural norms, values, and practices) to the commodification process of culture that transforms culture into capital, which is then used “like aces in a game of cards” (Bourdieu, 1989: 17) in the competition for social positions and scarce resources. Thus the notion of cultural capital highlights the vested interests in constructing and accentuating cultural differences, especially between the MNC home country culture and other cultures, because these distinctions can curb the competition for social positions, which, with increased globalization, has opened up to include a larger number of players.

Implications for Practice

There are also practical implications of this research. Human resource strategists strongly advocate the use of policies and practices that promote wider access to senior leadership opportunities in order to build an effective global social organization and fully integrate diverse employee groups within MNCs. This study suggests, however, that structural factors can lead to a disconnect between corporate policies and their perceived implementation (see also Mäkelä, Björkman, Ehrnrooth, Smale, & Sumelius, 2013), thus limiting their effectiveness. This has serious implications for how the HR function in MNCs conveys these policies to employees. Their efforts at implementation may be undermined from the beginning by the influence of the MNC’s social hierarchy and its effect on employees’ perceptions of the reality of the policies.

Second, MNCs are increasingly relocating critical assets overseas and therefore they depend on the knowledge and capabilities of employees who are dispersed throughout their firm’s global network. These transnational employees are thus becoming strategically important to MNCs’ global success, and firms often use practices that promote wider access to senior leadership opportunities in order to foster the organizational commitment and identification of these employees (Reade, 2001). Furthermore, these practices can be a powerful employment value proposition that enhances companies’ ability to recruit and retain skilled and experienced employees globally (Gowan, 2004). However, while communicating this proposition during the recruitment stage is crucial, this study also suggests that MNCs must make an effort to integrate new entrants into the organization through a concerted socialization process (Bauer, Bodner, Erdogan, Truxillo, & Tucker, 2007). In particular, the third and fourth levels of onboarding (Bauer, 2010) – culture and connection – are most important in this process. The culture level provides the new employee with an understanding of the organizational norms concerning the integration of diverse employee groups into the career opportunity structure, while the connection level helps the employee to build important interpersonal relationships and networks that will help reinforce these norms and facilitate global career opportunities. Thus the socialization process can be important to the creation of the cultural and social capital that non-HQ employees often need in order to have access to senior leadership positions.

Notes

It is important to note that the social hierarchy within organizations is embedded in both the wider societal context and in the formal structure of the organization.