Abstract

Along with other partners of key population groups, men who purchase sex (MWPS) contributed to around 18% of new reported HIV cases in 2018 among people aged 15–49 years worldwide. A systematic review was performed to evaluate interventions conducted to reduce HIV risk among MWPS in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). A comprehensive search of studies published in Embase, Medline, Global Health, Scopus, and Cinahl was performed. Among 32,115 studies found, 21 studies met the review’s inclusion criteria. Only four studies recruited MWPS, while the rest recruited groups often used as proxy populations for MWPS. The interventions were made primarily to increase HIV-related knowledge or perceptions through education and to improve condom usage rates through promotion and distribution. Few studies evaluated the impact of interventions on HIV testing rates and none looked at HIV treatment. Given the important role of testing as a prevention gate, together with UNAIDS’ 90-90-90 testing and treatment coverage goals for people infected with HIV, more studies which evaluate the impact of HIV testing and treatment provision among this group are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2006, 9–10% of men globally were estimated to pay for sex with female sex workers (FSWs) [1], 11.8% of whom living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) were HIV-infected [2]. Many of those men were adolescents or young adults [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13], and overlap with other key population groups such as men who have sex with men (MSM) [14, 15], people who inject drugs (PWIDs) [13, 16], and sex workers themselves [15]. Studies also report high numbers of sexual partners among this group, including multiple FSWs [17] as well as partners from low-risk groups [17], highlighting the importance of this group in bridging the onward HIV transmission from key to lower-risk populations. In 2018, UNAIDS estimated that 18% of global new HIV infections among people aged 15–49 years were among men who purchase sex (MWPS), and sexual partners of other key population groups [18].

Effective measures for HIV prevention are available. These include behavioural interventions and biomedical ones such as condoms, and HIV testing and treatments. UNAIDS recommends that key populations have access to combinations of such prevention services, and highlights the lack of interventions that combine measures [19]. However, there is limited information available to appraise and summarise interventions conducted to reduce the risk of HIV infection among MWPS in LMICs.

One systematic review of HIV interventions conducted among MWPS in LMICs did not particularize MWPS, but rather grouped them together with sex workers [20], with the result that none of the studies included focused solely on MWPS. It is, therefore, necessary to extend the previous systematic review study.

The current systematic review aims to extend the previous analysis to:

-

1.

Map and characterize the HIV prevention interventions targeting MWPS in LMICs, and

-

2.

Summarize the impact of such interventions on reducing the risk of HIV among MWPS and identify existing gaps and opportunities for future interventions.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement was used to guide the development of the report [21].

Information Search

Studies were included if they (1) evaluated interventions to reduce the risk of HIV infection either in: (a) MWPS or proxy populations used to represent MWPS, or (b) populations within which there was stratification by MWPS, (2) were conducted in LMICs, and (3) were published up until September 2016.

To assess programme effectiveness, studies were deemed eligible if they used either follow-up observations or parallel comparison groups within the same population, i.e. if they compared outcomes: (1) of serial surveys, including before-and-after interventions within the same population, or at baseline and follow-up surveys made at any time; or (2) between intervention and control groups.

A comprehensive search was conducted within Embase, Medline, Global Health, Scopus, and Cinahl databases. Search terms covered the main building blocks of HIV, FSWs, and MWPS. Because MWPS are also typically associated with particular occupation groups often used as proxies for MWPS, the building blocks were expanded to include other relevant terms. The search was then modified depending upon the terms and Boolean operators used in each database, as shown in Table 1.

All retrieved articles were exported into EndNote X7. Duplicates within and between databases were removed by using a command in EndNote X7, and by visual inspection for similarities among study characteristics such as titles, authors, and years. Articles were then excluded if they were letters to editors, commentary, or systematic review/review/meta-analysis studies, or not published in a peer-reviewed journal. All article titles or abstracts were then read to ascertain their relevance to our study aim, i.e. referring to HIV interventions among MWPS or proxy populations in LMICs. Full texts of potentially eligible articles were obtained and further assessed for final inclusion. These processes were conducted in two rounds. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were the same for each, with a focus on the detail of the review in the second round. Only studies with the full text in English were included in the analysis.

To avoid double publication bias, only one article of studies published more than once was selected. However, if these studies published different outcomes or intervention strategies in each publication, both were included.

LPLW was responsible for the entire process, with referral to RG and JK to resolve queries.

Method of Extraction

Criteria for a systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions [22] were used to guide the requisite information to be extracted from the articles. For each article, we extracted information about study participants, descriptions of interventions, follow-up observation period, comparison group/s, and outcomes. Other data, relating to author/s, publication year, country, study design, study settings, sample size, sampling technique, and theoretical framework used was also extracted.

Results

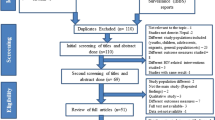

32,115 studies were found; 7034 duplicates were excluded. After a reading of titles and/or abstracts, a further 24,957 studies were excluded due to the topic not referring to HIV interventions among MWPS or proxy populations, resulting in 124 studies being screened for the full text. Of those, 103 were excluded on the bases of study design, full text not in English/not available, no comparison groups or follow-up observations, duplication, no clear interventions, target groups, or outcomes, or high-income country settings. Ultimately, 21 studies were yielded for inclusion in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Study Characteristics

These 21 research reports were from 14 countries. India contributed four studies, the highest percentage of all countries in which studies were conducted. Studies were published between 1997 and 2015. Study designs encompassed trial, cohort study, and secondary analysis of routinely collected data or national surveys, with the majority being serial surveys. Only four studies recruited MWPS, while almost all others recruited mobile populations from particular occupation groups often used as proxies for MWPS, considered by the original authors (as reflected in their background sections) to be highly exposed to commercial sex contact. These populations included army and military personnel, mine workers, and truck company workers; most studies recruited truck drivers (10 studies). Study settings included clinics, military areas, sex work venues, transport terminals, immigration checkpoints, ports, and truck-stops (Table 2).

Intervention Characteristics

The content of the interventions varied, covering: (1) law enforcement, (2) community forums or social gatherings, (3) health education interventions, (4) condom promotion or distributions, (5) sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing provision, and 6) HIV testing provision. Health education interventions comprised the largest intervention type, and took the following forms: media campaigns, hotline services, distribution of outdoor printed promotional materials, posters, billboards, education sessions, and counselling, interpersonal communication, workshops, training, or peer education. Except for two studies which solely evaluated health education interventions, all other studies assessed programmes combining health education with other intervention types noted above. While condom promotion or distribution was also the largest intervention type (18 studies), provision of STI testing was evaluated in only eight studies; six studies assessed interventions involving HIV testing provision; and none addressed HIV treatment. The range of intervention settings included clinics, media platforms, occupational sites, sex venues, and transport hubs. Follow-up periods varied from two months to 5 years (Table 3).

The Effect of Interventions on HIV-Related Outcomes

To assess the impact of interventions, a range of behavioural and biological outcomes was reported. These included extent of HIV/STI-related knowledge and perceptions/beliefs/motivations (13 studies), rates of condom use (20 studies), number of FSW contacts or engagement with transactional sex (15 studies), number of visits to STI clinics (3 studies), HIV testing rates (6 studies), STI prevalence or incidence (12 studies), and HIV prevalence or incidence (7 studies). Some studies also reported programme coverage, including the number of people exposed to the interventions or the number of men reached by the activity (9 studies) (Table 3).

The impacts of interventions were measured by comparing these outcomes among comparison groups, or by follow-up observations. As Table 3 shows, in its comparison of study characteristics, some studies did not provide the p value to ascertain statistically significant differences, while others reported that value.

While interventions to improve knowledge or perceptions of HIV had mixed results, most (9 out of 13 studies which measured changes in knowledge/perceptions of HIV) reported statistically significant results in the expected direction, i.e. in favour of improving HIV-related knowledge and perceptions. A change in condom use behaviours was also an apparently easy-to-achieve outcome. Of 20 studies reporting changes in the rates of condom use, 13 reported a statistically significant increase in/higher rate of condom use in their follow-up observation or intervention groups. Among the 15 studies measuring the rates of engagement or contact with FSWs, seven reported a statistically significant decrease in/lower rate of FSWs contact in the follow-up observation or intervention group (Table 3).

Only two of six studies measuring changes in HIV testing rates noted a significant increase in HIV testing rates in their follow-up groups, in the order of no more than 30% of the participants tested at the end of the interventions. Of the 12 studies which measured changes in STI rates, eight reported a significant decline in STI rates in their follow-up or intervention groups. Three of the four studies not reporting a significant decline in STI rates did not provide STI testing for the men, focusing instead on health education and or condom distribution. Among the seven studies measuring changes in HIV prevalence or incidence rates, only two noted a statistical reduction in HIV prevalence or incidence rates among their follow-up or intervention groups (Table 3).

Owing to the broad range of study participants, intervention types and combinations, follow-up periods, comparison groups, and outcomes of interests, a meta-analysis was not performed.

Assessment of Study Quality

The quality of all included studies was assessed using the STROBE checklist [23]. In accord with our inclusion criteria, only five studies used randomised controlled trial (RCT) designs (Table 2). Fourteen studies attempted to reduce bias by selecting their sample using a probability sampling method (Table 4). Six studies provided clear justifications for their sample size (Table 4). Eighteen studies reported on the statistical significance of their outcomes (Table 3).

Discussion

This review found a limited number [21] of studies matching its inclusion criteria. Among the 21 studies reviewed here, only four were conducted directly among MWPS. The paucity of studies in the published literature measuring the effectiveness of interventions to reduce the risk of HIV infection is at odds with the significant contribution of new HIV infections reported among this group to the overall number of new reported HIV cases globally [24]. The limited attention and effort to target MWPS could be explained by the clandestine nature of this population: the challenges of identifying this hard-to-reach group (1), let alone implementing interventions, are considerable. As an alternative, men from particular occupation groups thought to be highly exposed to commercial sex activities are often used as proxies for MWPS and sought for interventions targeting this population. Further, targeting these occupational groups may be less stigmatising than approaching men for HIV prevention programmes directly in the transactional sex context.

Programme coverage or uptake, i.e. the percentage of participants exposed to or receiving interventions prior to conclusions being drawn about the impact of an intervention [25], is an essential factor influencing programme effectiveness [26, 27]. A study of FSWs, for example, found a correlation between programme exposure and condom use and HIV testing rates [28]. Despite its importance, only nine studies in the current review provided any such information on uptake or coverage of interventions. This questions conclusions about, first, whether the inadequate outcomes noted in some studies was due to poor exposure to, or the inefficacy of the programme itself; or second, whether the reported success of some others was due to the public health intervention itself, or to other influencing factors, such as parallel interventions conducted in the same settings [29,30,31,32], a more widespread HIV culture [31], or the nature of epidemic phases [27]. Future interventions and studies should, therefore, report such possible factors so that proper conclusions about intervention effectiveness can be drawn.

UNAIDS has advocated for intensification of combined behavioural interventions and condom distribution along with HIV testing [33]. The current review observed that interventions which were combined to improve HIV-related knowledge or perceptions and rates of condom use have often resulted in a statistically significant improvement in both these indicators.

The goal of having 90% of people living with HIV know their HIV status is one of their global indicators set by UNAIDS for health sector response [34]. Their 90-90-90 fast-track target emphasises the importance of HIV status awareness and HIV treatment in curbing the HIV epidemic [35], yet only six of the studies reviewed indicated HIV testing rates as one of their outcomes, and none looked at HIV treatment. Of the studies including HIV testing rates as one of their results, only two found a statistically significant improvement in testing rates of no more than 30% of study participants tested at the end of the study period. The challenges entailed in increasing the rates of HIV testing noted in the current review supports the argument highlighted in a recent editorial which declares that “the last big shared challenge remaining is testing” [36]. This opens opportunities for future studies targeting MWPS to evaluate other potentially effective strategies to improve HIV testing rates. Since WHO guidelines recommend HIV self-testing as a means of increasing rates [37,38,39], and various studies note the potential of this strategy to improve the coverage of testing among MWPS [40,41,42], implementation and evaluations of this strategy are worthy of future consideration.

This review has several limitations. First, most of the studies included in the analysis used questionnaires to reveal cognitive and behavioural changes among their participants. Sexual behaviour and HIV/AIDS are widely felt to be sensitive matters, and social desirability bias might have influenced outcomes measured by self-report [43, 44]. Second, only studies which measured changed outcomes against comparison or follow-up groups were included. There may have been studies that measured the effectiveness of interventions to reduce HIV risk among MWPS but, not meeting those criteria, they were not included in this review.

Challenges exist in comparing the effectiveness of interventions in relation to their outcomes because of the complexities of intervention packages and the scope of outcomes measured. Identifying the overall effectiveness of programmes is also problematic since data for other, possibly crucial factors that may have influenced reported outcomes, such as programme coverage or exposure was rarely included in studies. Follow-up timelines also varied significantly, making it difficult to estimate effect [45]. Different follow-up timelines might produce different outcomes, such as that noticed in the study by Jewkes et al. (2008). At that study’s 12-month follow-up, a significantly lower proportion of men reported transactional sex compared to the control group. That effect had, however, disappeared by the 24-month follow-up [46]. Quite a few studies did not provide a significant value in their statistical testing measuring changes in their outcomes, which also qualifies the conclusions drawn. Last, but not least, since the current review included only those studies published in a peer-reviewed journal, thus excluding those in grey literature, studies with non-statistically significant findings may have been missed.

Conclusions

This systematic review is the first that aimed to map and characterise HIV interventions conducted among MWPS in LMICs and identify extant gaps. A considerable paucity of published studies measuring the effectiveness of HIV interventions to change HIV-related outcomes among this population was noted. Among the studies included, only a few recruited MWPS; the balance looked only at proxy groups for this population. Most of the interventions reviewed were made to increase HIV-related knowledge or perceptions through education, or to improve condom usage rates via promotion and distribution. Almost all studies evaluated interventions combining health education interventions with other intervention types. Despite the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target, few studies evaluated the impact of HIV testing, and none assessed HIV treatment.

Interventions to improve HIV-related knowledge or perceptions and rates of condom use have often resulted in statistically significant improvements in both indicators. However, only six studies included HIV testing rates as one of their outcomes, and only two of them noted statistically significant improvements in testing rates, i.e. no more than 30% of their participants were tested at the end of the study. This finding emphasises the enormity of the challenges of testing asserted in a recent editorial [36]. In addition, the UNAIDS goal for 90% of all people living with HIV to know their HIV status indicates the necessity of sharper focus on HIV testing provision interventions to improve HIV testing uptake among MWPS. The HIV self-testing approach in particular, recommended by the WHO [39], and recently pilot trialled [42] is worth considering.

References

Carael M, Slaymaker E, Lyerla R, Sarkar S. Clients of sex workers in different regions of the world: hard to count. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(3):26–33.

Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker M, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):538–49.

Mulieri I, Santi F, Colucci A, Fanales-Belasio E, Gallo P, Luzi AM. Sex workers clients in Italy: results of a phone survey on HIV risk behaviour and perception. Annali dell'Istituto Superiore Sanita. 2014;50(4):363–8.

Goldenberg SM, Gallardo Cruz M, Strathdee SA, Nguyen L, Semple SJ, Patterson TL. Correlates of unprotected sex with female sex workers among male clients in Tijuana. Mexico Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(5):319–24.

McClair TL, Hossain T, Sultana N, Burnett-Zieman B, Yam EA, Hossain S, et al. Paying for sex by young men who live on the streets in Dhaka city: compounded sexual risk in a vulnerable migrant community. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(2):S29–S34.

Ng JYS, Wong M-L. Determinants of heterosexual adolescents having sex with female sex workers in Singapore. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0147110.

Xantidis L, McCabe MP. Personality characteristics of male clients of female commercial sex workers in Australia. Arch Sex Behav. 2000;29(2):165–76.

Ompad DC, Bell DL, Amesty S, Nyitray AG, Papenfuss M, Lazcano-ponce E, et al. Men who purchase sex, who are they? An interurban comparison. J Urban Health. 2013;90(6):1166–80.

Darling KE, Diserens EA, N'Garambe C, Ansermet-Pagot A, Masserey E, Cavassini M, et al. A cross-sectional survey of attitudes to HIV risk and rapid HIV testing among clients of sex workers in Switzerland. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(6):462–4.

Nadol P, Hoang TV, Le L, Nguyen TA, Kaldor J, Law M. High HIV prevalence and risk among male clients of female sex workers in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. AIDS Behav. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1751-4.

Reilly KH, Wang J, Zhu Z, Li SC, Yang T, Ding G, et al. HIV and associated risk factors among male clients of female sex workers in a Chinese border region. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(10):750.

Shaw SY, Parinita B, Isac S, Deering KN, Ramesh BM, Washington R, et al. A cross-sectional study of sexually transmitted pathogen prevalence and condom use with commercial and noncommercial sex partners among clients of female sex workers in Southern India. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(6):482–9.

Leng Bun H, Detels R, Heng S, Mun P. The role of sex worker clients in transmission of HIV in Cambodia. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(2):170–4.

Villarroel MA. Male clients of sex workers in the United States: correlates with STI/HIV risk behaviors and urbanization level. Sexually Transmitted Infections Conference: STI and AIDS World Congress. 2013;89.

Kolaric B. Croatia: still a low-level HIV epidemic?–seroprevalence study. Coll Antropol. 2011;35(3):861–5.

Wagner KD, Pitpitan EV, Valente TW, Strathdee SA, Rusch M, Magis-Rodriguez C, et al. Place of residence moderates the relationship between emotional closeness and syringe sharing among injection drug using clients of sex workers in the US-Mexico border region. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(6):987–95.

Niccolai LM, Odinokova VA, Safiullina LZ, Bodanovskaya ZD, Heimer R, Levina OS, et al. Clients of street-based female sex workers and potential bridging of HIV/STI in Russia: results of a pilot study. AIDS Care. 2012;24(5):665–72.

UNAIDS. Global AIDS update 2019—Communities at the centre. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2019.

UNAIDS. On the Fast-Track to end AIDS: UNAIDS Strategy 2016–2021 Geneva 2015.

Wariki WM, Ota E, Mori R, Koyanagi A, Hori N, Shibuya K. Behavioral interventions to reduce the transmission of HIV infection among sex workers and their clients in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Libr. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005272.pub3.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;8(5):336–41.

Jackson N, Waters E. Criteria for the systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions. Health Promot Int. 2005;20(4):367–74.

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1500–24.

UNAIDS. UNAIDS Data 2017. UNAIDS; 2017.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1989;89:1322–7.

Hargreaves JR, Delany-Moretlwe S, Hallett TB, Johnson S, Kapiga S, Bhattacharjee P, et al. The HIV prevention cascade: integrating theories of epidemiological, behavioural, and social science into programme design and monitoring. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(7):e318–e322322.

Hayes R, Kapiga S, Padian N, McCormack S, Wasserheit J. HIV prevention research: taking stock and the way forward. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 4):S81–S92.

Armstrong G, Medhi GK, Kermode M, Mahanta J, Goswami P, Paranjape RS. Exposure to HIV prevention programmes associated with improved condom use and uptake of HIV testing by female sex workers in Nagaland, Northeast India. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):476.

Celentano DD, Nelson KE, Lyles CM, Beyrer C, Eiumtrakul S, Go VFL, et al. Decreasing incidence of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases in young Thai men: evidence for success of the HIV/AIDS control and prevention program. AIDS. 1998;12(5):F29–F36.

Lipovsek V, Amajit M, Deepa N, Pritpal M, Aseem S, Roy KP. Increases in self-reported consistent condom use among male clients of female sex workers following exposure to an integrated behaviour change programme in four states in southern India. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(Suppl. 1):i25–i32.

Tambashe BO, Speizer IS, Amouzou A, Djangone AM. Evaluation of the PSAMAO "Roulez Protege" mass media campaign in Burkina Faso. Prevention du SIDA sur les Axes Migratoires de l'Afrique de l'Ouest. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(1):33–48.

Lowndes C, Alary M, Labbe A, Gnintoungbe C, Belleau M, Mukenge L, et al. Interventions among male clients of female sex workers in Benin, West Africa: an essential component of targeted HIV preventive interventions. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:577–81.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Fast-tracking combination prevention: towards reducing new HIV infections to fewer than 500 000 by 2020. Geneva 2015.

World Health Organisation. Consolidated strategic information guidelines for HIV in the health sector. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2015.

UNAIDS. 90-90-90 An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic: UNAIDS; 2014 [cited 2018 6 March]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en.pdf.

The Lancet HIV. Divergent paths to the end of AIDS. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(9):e375.

World Health Organisation. Consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services. Geneva: WHO; 2015.

World Health Organisation. Guidelines on HIV self-testing and partner notification: supplement to consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2016.

World Health Organisation. WHO recommends HIV self testing—evidence update and considerations for success. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2019.

Thirumurthy H, Akello I, Murray K, Masters S, Maman S, Omanga E, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of a novel approach to promote HIV testing in sexual and social networks using HIV self-tests. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:22–3.

Wulandari LPL, Kaldor J, Guy R. Brothel-distributed HIV self-testing by lay workers improves HIV testing rates among men who purchase sex in Indonesia. 2018 Australasian HIV&AIDS Conference; Sydney 2018.

Wulandari LPL, Kaldor J, Guy R. Uptake and acceptability of assisted and unassisted HIV self-testing among men who purchase sex in brothels in Indonesia: a pilot intervention study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:730. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08812-4.

Schick V, Calabrese SK, Herbenick D. Survey methods in sexuality research. Am Psychol Assoc. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1037/14193-004.

DiFranceisco W, McAuliffe TL, Sikkema KJ. Influences of survey instrument format and social desirability on the reliability of self-reported high risk sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 1998;2(4):329–37.

Schaefer R, Gregson S, Fearon E, Hensen B, Hallett TB, Hargreaves JR. HIV prevention cascades: a unifying framework to replicate the successes of treatment cascades. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(1):e60–e6666.

Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Dunkle K, Puren A, et al. Impact of Stepping Stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337(7666):391–5.

Jackson DJ, Rakwar JP, Richardson BA, Mandaliya K, Chohan BH, Bwayo JJ, et al. Decreased incidence of sexually transmitted diseases among trucking company workers in Kenya: results of a behavioral risk-reduction programme. Aids. 1997;11(7):903–9.

Celentano DD, Bond KC, Lyles CM, Eiumtrakul S, Go VF, Beyrer C, et al. Preventive intervention to reduce sexually transmitted infections: a field trial in the Royal Thai Army. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(4):535–40.

Lau JT, Wong WS. Behavioural surveillance of sexually-related risk behaviours for the cross-border traveller population in Hong Kong: the evaluation of the overall effectiveness of relevant prevention programmes by comparing the results of two surveillance surveys. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11(11):719–27.

Laukamm-Josten U, Mwizarubi BK, Outwater A, Mwaijonga CL, Valadez JJ, Nyamwaya D, et al. Preventing HIV infection through peer education and condom promotion among truck drivers and their sexual partners in Tanzania, 1990–1993. AIDS Care. 2000;12(1):27–40.

Leonard L, Ndiaye I, Asha K, Eisen G, Diop O, Mboup S, et al. HIV prevention among male clients of female sex workers in Kaolack, Senegal: results of a peer education program. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12(1):21–37.

Bronfman M, Leyva R, Negroni MJ. HIV prevention among truck drivers on Mexico's southern border. Cult Health Sex. 2002;4(4):475–88.

Williams BG, Taljaard D, Campbell CM, Gouws E, Ndhlovu L, Dam JV, et al. Changing patterns of knowledge, reported behaviour and sexually transmitted infections in a South African gold mining community. AIDS. 2003;17(14):2099–107.

Ross MW, Essien EJ, Ekong E, James TM, Amos C, Ogungbade GO, et al. The impact of a situationally focused individual human immunodeficiency virus/sexually transmitted disease risk-reduction intervention on risk behavior in a 1-year cohort of Nigerian military personnel. Mil Med. 2006;171(10):970–5.

Cornman DH, Schmiege SJ, Bryan A, Benziger TJ, Fisher JD. An information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model-based HIV prevention intervention for truck drivers in India. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(8):1572–84.

Bing EG, Cheng KG, Ortiz DJ, Ovalle-Bahamon RE, Ernesto F, Weiss RE, et al. Evaluation of a prevention intervention to reduce HIV Risk among Angolan soldiers. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(3):384–95.

Lau JTF, Wan SP, Yu XN, Cheng F, Zhang Y, Wang N, et al. Changes in condom use behaviours among clients of female sex workers in China. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85(5):376–82.

Lafort Y, Geelhoed D, Cumba L, Lazaro C, Delva W, Luchters S, et al. Reproductive health services for populations at high risk of HIV: performance of a night clinic in Tete province, Mozambique. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:144.

Lau JT, Tsui HY, Cheng S, Pang M. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the relative efficacy of adding voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) to information dissemination in reducing HIV-related risk behaviors among Hong Kong male cross-border truck drivers. AIDS Care. 2010;22(1):17–28.

Pandey A, Mishra RM, Sahu D, Benara SK, Sengupta U, Paranjape RS, et al. Heading towards the Safer Highways: an assessment of the Avahan prevention programme among long distance truck drivers in India. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(6):S15.

Bai RL, Surya AV, Balasubramaniam R. Increasing awareness on prevention of HIV/AIDS in the clients of sex workers influencing their safe sexual practices. Int J BioSci Technol. 2012;5(13):67–75.

Himmich H, Ouarsas L, Hajouji FZ, Lions C, Roux P, Carrieri P. Scaling up combined community-based HIV prevention interventions targeting truck drivers in Morocco: effectiveness on HIV testing and counseling. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:208.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wulandari, L.P.L., Guy, R. & Kaldor, J. Systematic Review of Interventions to Reduce HIV Risk Among Men Who Purchase Sex in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Outcomes, Lessons Learned, and Opportunities for Future Interventions. AIDS Behav 24, 3414–3435 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02915-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02915-0