Abstract

Our aim was to test our laparoscopic simulator for construct validity and for establishing performance standards. The skills of laparoscopic novices (n = 18) and advanced gynaecologists (experts, n = 5) were tested on our inanimate simulator by their performance of five tasks. The sum score was the sum of scores of all five tasks. We calculated the scores by adding completion time and penalty points. After baseline evaluation, the novices were assigned to five weekly training sessions (n = 8, training group) or no training (n = 10, control group). Both groups were retested. The experts were tested once, and their performance was compared with the baseline scores of all novices to establish construct validity. The training group improved significantly in all tasks. The final scores of the trained group were significantly better than those of the control group. The training group reached a plateau within seven trials, except for intra-corporeal knot tying. During final testing, the trained group reached the experts’ level of skills on the simulator. We concluded that our simulation model has construct validity. Novices can reach the experts’ basic laparoscopic skills level on the simulator after a short and intense simulator training course. Experts’ basic skills level on the simulator is an achievable performance standard during residency training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Laparoscopy has become the method of choice for many open procedures. This minimally invasive way of access has considerable benefits for patients, such as reduced morbidity, shorter hospitalisation, better cosmetic results, and earlier return to normal activity [1].

The performance of laparoscopic surgery requires psychomotor skills that are different from those needed to perform open surgical procedures and result in long learning curves [2]. These skills include the shift from a three-dimensional operating field to a two-dimensional monitor display, judgment of altered perception of depth and spatial relationships, distorted eye–hand coordination, adaptation to the fulcrum effect, manipulation of long surgical instruments while adjusting for amplified tremor, diminished tactile feedback and fewer degrees of freedom [3].

In addition to the difficulties of acquiring laparoscopic skills, issues such as quality control, patient safety, financial constraints, efficiency and cost effectiveness and less exposure to the operating room have resulted in the need for skills training outside the operating room [3, 4].

Simulators are devices that recreate operating conditions as a substitute for real life performance, and they play an increasingly important role in training basic laparoscopic skills. Simulator technology was initially proven to be a useful teaching tool in aviation; nowadays, it has great potential for training [5–9] and objectively assessing laparoscopic skills [4–6, 9–11]. Simulator training is shown to be effective in providing skills that are transferable to the operating room [12–14].

Nowadays, new curricula are being established, with the laparoscopic simulator as an integral component of the residency curriculum [15]. In our institution we developed a skills laboratory with an inanimate five-task laparoscopic simulation model for training and evaluation of laparoscopic skills. The aim of our study was twofold: to demonstrate construct validation of our simulation model, which is the ability of a simulator to discriminate between persons with different skills levels (e.g. novice or expert) [4, 16] and to analyse the feasibility of setting experts’ skills levels on the simulator as a performance standard.

Material and methods

This study was performed in the skills laboratory located in the Department of Gynaecology at the Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC), in The Netherlands. The simulator was designed (F.W.J.) and fabricated at the LUMC. It consisted of an inanimate five-task box trainer with a non-transparent cover, measuring 45 cm × 30 cm × 25 cm using a 0° scope.

Outcome measures

The individual’s performance on the box trainer was measured using a scoring system that rewarded precision and speed. During each task the time to completion (seconds) and penalty points were measured. Scores were calculated by the addition of completion time and penalty points, thus rewarding both speed and precision (score = time + penalty points). This scoring system rewarded faster and more accurate performance with lower scores. Besides a score for each task, a sum score was calculated, which was defined as the sum of scores of all five tasks. All participants were instructed on how to perform the five tasks and how penalty points were obtained by watching a 10-min introduction video-tape. No practising was permitted before testing, and the five tasks were performed in a set order.

Tasks

The tasks in this study, as well as the scoring system, were based on the studies of Derossis et al. [17] and are shown in Fig. 1.

-

1.

Pipe cleaner

This task involved the placement of a pipe cleaner though four small rings. A penalty was calculated when a ring was missed. Score = time in seconds + (the number of missed rings ×10).

-

2.

Placing rubber band

This task required the participant to stretch a rubber band around 16 nails on a wooden board. A penalty was calculated when the rubber band was not stretched around a nail at the end of the task. Score = time in seconds + (the number of missed nails ×10).

-

3.

Placing beads

This task involved the individual’s placing 13 beads to form a letter “B”. A penalty was calculated when a bead was dropped next to the pegboard. Score = time in seconds + (the number of dropped beads ×10).

-

4.

Cutting circle

This task required the participant to cut a circle from a rubber glove stretched over 16 nails in a wooden board. Penalty points were calculated when the individual deviated from cutting on the line. Score = time in seconds + surface of glove in milligrammes deviated from the circle.

-

5.

Intra-corporeal knot tying

This task involved the tying of an intra-corporeal knot (two turn, square knots) in a foam uterus. A penalty was calculated to reflect the security (slipping or too loose) of the knot. Score = time in seconds + 10 when knot was slipping or loose.

Construct validity

Five gynaecologists with extensive experience in advanced laparoscopy (“experts” who had performed more than 100 advanced laparoscopic procedures) were invited to complete the five simulator tasks once. Their scores were compared with the novices’ baseline evaluation in order to establish construct validity.

Effect of training

A total of 18 medical students (novices) volunteered to participate in the study. They were in their 2nd–5th years as medical students at LUMC and had had no experience of simulator training or clinical laparoscopy prior to, or during, the study period.

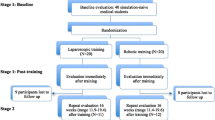

After baseline testing on the simulator, the novices were assigned to either five weekly training sessions on a simulator (training group, n = 8) or a control group (n = 10). Assignment was not randomized but was based on availability of the student during the study period. The control group and training group were then again measured at a final testing, as shown in Fig. 2. The control group received no skills training. During baseline testing, all five training sessions and final testing, the novices completed all five tasks once. This meant that at the end of the study the training group had completed all tasks a total of seven times (one baseline test, five training sessions, one final test), which will be referred to in this manuscript as seven trials. These results were analysed for the effect of repetition (learning curve). The plateau of the learning curve was established when no statistical difference was shown between trials.

Performance standard

The performance of the experts was compared with the results of the trained novices (final test) so that we could determine whether the experts’ basic skills level was feasible as a performance standard for laparoscopic novices on our simulator.

Statistics

The data collected were analysed by the SPSS 12.0 software package (SPSS, Chicago, Ill., USA). Statistical analyses were performed using the chi-square test, paired t-test, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, the Mann–Whitney test, Friedman’s test and Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test. P values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 shows that the demographic characteristics of the training group (n = 8) and the control group (n = 10) were comparable (median ages 22 years and 21 years, respectively (Mann–Whitney test P = 0.14). The training group consisted of three male and five female students, and the control group was composed of six male and four female student (Fisher’s exact test P = 0.63). There were no dropouts throughout the study.

Construct validity

The median scores of the participants are stated in Tables 2, 3 and 4 and Fig. 3. Comparison between experts (n = 5) and novices (n = 18) demonstrated significant difference for all five tasks and sum score in favour of the experts (Mann–Whitney test: pipe cleaner P < 0.001; rubber band P = 0.007; beads P < 0.001; circle cutting P = 0.001; knot tying P < 0.001; sum score P < 0.001). This meant that the experts performed the tasks significantly faster and more accurately than did the novices during their baseline testing.

Effect of training

At baseline testing no significant differences were seen between the training group and the control group (Mann–Whitney test). The training group improved significantly in all five tasks and sum score (Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test: all P < 0.02). The final testing scores of the training group were significantly better than those of the control group for all the five tasks (Mann–Whitney test: pipe cleaner P < 0.001; rubber band P = 0.04; beads P = 0.02; circle-cutting P = 0.009; intra-corporeal knot tying P < 0.001) and sum score (P < 0.001).

The training group had a total of seven trials, which represented the novices’ learning curve on our simulation model. Their individual sum scores of these seven trials are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 3. The five individual task scores and sum score improved significantly after seven trials (Friedman test: pipe cleaner P = 0.002; rubber band P < 0.001; beads P < 0.001; circle cutting P < 0.001; intra-corporeal knot tying P < 0,001). The relation between trial number (1–7) and sum score was analysed: the correlation coefficients (Pearson) between number of trial and weekly sum score for each individual were strongly negative (inversely proportional) and statistically significant (all individuals P < 0.05).

To reach a plateau in the learning curve, the novices had to perform a mean of two trials for the pipe cleaner task, five for the rubber band, seven for the beads and five for the circle cutting. The only task where a plateau was not reached within seven trials was the intra-corporeal knot tying (paired t-test).

Performance standard

Within seven trials, the trained novices reached the experts’ skills level in all tasks and sum score, as shown in Table 2. When the scores of the novices’ seventh trial (final test of the training group) were compared with the experts’ scores on our simulator, no significant differences were found for any of the five tasks, as shown in Table 4 (Mann–Whitney test: pipe cleaner P = 0.13; rubber band P = 0.44; beads P = 0.9; circle cutting P = 0.8; intra-corporeal knot tying P = 0.09) and sum score (P = 0.9).

Discussion

Our inanimate simulation model is able to distinguish reliably between the performance levels of expert laparoscopists and novices. Therefore, the simulator has construct validity. Furthermore, our simulation model is a successful device for training and measuring skills objectively. Experts’ basic skills levels on the simulator as a performance standard is feasible, given that laparoscopic novices can be trained to reach experts’ basic skills levels on a simulator after a short and structured simulator training programme.

The tasks in this study, as well as the scoring system, were based on the studies of Derossis et al. [17] In her studies these tasks on the inanimate laparoscopic simulator were validated, and it was established that practice with the simulator resulted in improved performance in vivo. Therefore, for our study, we decided not to repeat these investigations, since the beneficial aspects of simulator training for “live” laparoscopic skills had previously been shown.

The major advantage of using goal-orientated training, such as performance standards, is the consistency of the final result, since all residents are expected to reach the performance standard. For residents with outstanding ability, minimal practice may be required. For those who require more practice, appropriate training may be scheduled until the predetermined level of performance is accomplished. In addition, residents are competitive and thrive from having a target to achieve [16].

Of the five tasks on our simulator, intra-corporeal knot tying was considered the most difficult. Although intra-corporeal knot tying is not a frequently performed clinical procedure, the ability to perform advanced laparoscopic procedures is required. The experts participating in this study were experienced in intra-corporeal suturing during laparoscopic procedures. Furthermore, the intra-corporeal knot-tying task mimics all the skills mentioned above. Therefore, it is our opinion that intra-corporeal knot tying is an outstanding task to be trained on a simulator.

Statistical analyses showed that after seven trials of intra-corporeal knot tying the novices had a higher (worse) mean score than the experts had. However, those scores showed no significant difference. In addition, the novices had not yet reached a plateau in their learning curve for intra-corporeal knot tying after the seven trials. From these data we conclude that, statistically, novices can reach expert level after seven trials; however, more training is needed to establish a plateau in the learning curve and actually to reach expert level on the simulator.

The pipe cleaner and rubber band tasks were chosen as the first two tasks and were considered relatively simple. However, these tasks are important to start the training with, due to their simplicity. In addition, they train hand–eye coordination and the lack of depth perception by making the participant work with two instruments, as well as the camera. Of the other tasks, the beads task resembles laparoscopic sterilization, in which one hand is used to operate the camera and the other to complete the task or procedure, and the circle-cutting task resembles a cystectomy, where precision is required.

Skills are expected to improve with increased training and repetition. We found that the novices’ performances improved and they reached the experts’ skills level on the simulator. In order to reach maximum results, residents should, in our opinion, be trained early in their residency training, when they are still inexperienced in laparoscopic surgery. For the residents to obtain the experts’ level of basic laparoscopic skills on the simulator, a short training course, as is described in this study, is certainly feasible during residency. The retention of skills after training, and the frequency of training necessary to maintain skills, is not well established yet and requires further study [18–20].

The results of our study provide a firm basis for the simulation model to be implemented as mandatory in the residency training curriculum, with the laparoscopic experts’ performance level as the training goal. Our first-year residents are subject to a short and structured, performance, standard-based curriculum on our simulator to ensure they have basic laparoscopic skills before they perform laparoscopy in the operating room. We need to keep in mind that the simulator trains basic laparoscopic skills, not laparoscopic surgery. It is our opinion that basic laparoscopic skills should be learned in a skills laboratory and that the performance of laparoscopic procedures is learned in the operating room. Further study will show the retention of skills after our performance standard-based curriculum and optimal frequency of simulator training.

References

Darzi A, Mackay S (2002) Recent advances in minimal access surgery. BMJ 423:31–34

Lehmann KS, Ritz JP, Maass H, Cakmak HK, Kuehnapfel UG, Germer CT, Bretthauer G, Buhr HJ (2005) A prospective randomized study to test the transfer of basic psychomotor skills from virtual reality to physical reality in a comparable training setting. Ann Surg 241:442–449

Munz Y, Kumar BD, Moorthy K, Bann S, Darzi A (2004) Laparoscopic virtual reality and boxtrainers. Is one superior to the other? Surg Endosc 18:485–494

Fried GM, Feldman LS, Vassiliou MC, Fraser SA, Stanbridge D, Ghitulescu G, Andrew CG (2004) Proving the value of simulation in laparoscopic surgery. Ann Surg 240:518–528

Derossis AM, Antoniuk M, Fried GM (1999) Evaluation of laparoscopic skills: a 2-year follow-up during residency training. Can J Surg 42:293–296

Jordan JA, Gallagher AG, McGuigan J, McClure N (2001) Virtual reality training leads to faster adaptation to the novel psychomotor restrictions encountered by laparoscopic surgeons. Surg Endosc 15:1080–1084

Lentz GM, Mandel LS, Lee D, Gardella C, Melville J, Goff BA (2001) Testing surgical skills of obstetrics and gynecologic residents in a bench laboratory setting: validity and reliability. Am J Obstet Gynecol 184:1462–1470

Rosser JC, Rosser LE, Savalgi RS (1997) Skill acquisition and assessment for laparoscopic surgery. Arch Surg 132:200–204

Scott DJ, Young WN, Tesfay ST, Tesfay ST, Frawley WH, Rege RV, Jones DB (2001) Laparoscopic skills training. Am J Surg 182:137–142

Fraser SA, Klassen DR, Feldman LS, Ghitulescu GA, Stanbridge D, Fried GM (2003) Evaluating laparoscopic skills: setting the pass/fail score for the MISTELS system. Surg Endosc 17:964–967

Reznick R, Regehr G, MacRae H, Martin J, McCulloch W (1997) Testing technical skill via an innovative "bench station" examination. Am J Surg 173:226–230

Grantcharov TP, Kristiansen VB, Bendix J, Bardram L, Rosenberg J, Funch-Jensen P (2004) Randomized clinical trial of virtual reality simulation for laparoscopic skills training. Br J Surg 91:146–150

Hamilton EC, Scott DJ, Fleming JB, Rege RV, Laycock R, Bergen PC, Tesfay ST, Jones DB (2002) Comparison of video trainer and virtual reality training systems on acquisition of laparoscopic skills. Surg Endosc 16:406–411

Hyltander A, Liljegren E, Rhodin PH, Lonroth H (2002) The transfer of basic skills learning in a laparoscopic simulator to the operating room. Surg Endosc 16:1324–1328

Jakimowicz JJ, Cuschieri A (2005) Time for evidence-based minimal access surgery training—simulate or sink. Surg Endosc 19:1521–1522

Korndorffer JR Jr, Clayton JL, Tesfay ST, Brunner WC, Sierra R, Dunne JB, Jones DB, Rege RV, Touchard CL, Scott DJ (2005) Multicenter construct validity for Southwestern laparoscopic videotrainer stations. J Surg Res 128:114–119

Derossis AM, Fried GM, Abrahamowicz M, Sigman HH, Barkun JS, Meakins JL (1998) Development of a model for training and evaluation of laparoscopic skills. Am J Surg 175(6):482–487

Stefanidis D, Korndorffer JR Jr, Sierra R, Touchard C, Dunne JB, Scott DJ (2005) Skill retention following proficiency-based laparoscopic simulator training. Surgery 138:165–170

Stefanidis D, Korndorffer JR Jr, Markley S, Sierra R, Scott DJ (2006) Proficiency maintenance: impact of ongoing simulator training on laparoscopic skill retention. J Am Coll Surg 2024:599–603

Torkington J, Smith SG, Rees B, Darzi A (2001) The role of the basic laparoscopic skills course in the acquisition and retention of laparoscopic skill. Surg Endosc 15:1071–1075

Acknowledgements

We thank all the students and gynaecologists for participating in our study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kolkman, W., van de Put, M.A.J., Wolterbeek, R. et al. Laparoscopic skills simulator: construct validity and establishment of performance standards for residency training. Gynecol Surg 5, 109–114 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-007-0345-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-007-0345-y