Abstract

A questionnaire survey was conducted with the aim of examining the problems involved in the disposal of infectious waste at home-visit nursing stations and in its handling during home visits by nurses. From among the home-visit nursing stations registered with the National Association for Home-Visit Nursing Care, 1,965 offices were selected at random and questionnaires were sent to the selected offices. Nurses at 1,314 offices (66.9 %) responded to the survey and responses from 1,283 offices were identified as suitable for analysis after excluding 26 offices that closed and five offices whose main field of care was psychiatry. Offices were classified by management configuration. Offices attached to hospitals were classified as “attached office” and all others were classified as “independent office”. More attached office nurses recovered medical waste from patients’ homes than did independent office nurses. They were also more likely to transport waste with them during the course of a day’s visits. There was a significant difference between attached and independent offices in the burden of expense for waste disposal. Both offices have strong concern about waste treatment containers and handling in improvement in home medical care (HMC) waste disposal. Thus, in order to alleviate these concerns, it is necessary to provide nurses with containers for medical waste suited to home-visit nursing care and tools for preventing injuries. Japanese government should address HMC waste disposal more comprehensively through necessary legislation, subsidization and standardization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

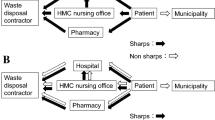

Recently, home medical care (HMC) services have become more prominent and widespread in Japan. In 2008, 5,434 HMC stations had been operating. [1]. About half of the HMC stations are affiliated with hospitals [1]. Domestic medical waste is a constant concern and growing problem with HMC. The Japanese Waste Disposal and Public Cleansing Law classifies waste materials as either industrial waste or municipal solid waste [2]. Industrial waste results from business activities and municipal solid waste refers to waste other than industrial waste. Infectious waste from hospitals or clinics is classified as specially controlled industrial waste [3]. However, HMC waste is classified as specially controlled municipal solid waste. Municipalities are responsible for disposal of specially controlled municipal solid waste which contains this HMC waste. However, many municipalities do not collect some or all HMC waste due to fears of infection or sharp [4–6]. Home-visit nurses often collect HMC waste that is not collected by municipalities and the safety of such waste is left to the care of the nurses. There have been few studies on occupational injuries resulting from HMC waste collection. In addition, these studies are small number of samples [6–10] and there is a bias in the region [7–9] or low response rate [8]. The purpose of this study is to investigate the current burdens placed on home-visit nurses in regards to HMC waste collection and identify specific problems.

Subjects and methods

To determine current practices in the disposal and handling of HMC waste, a questionnaire was formulated and mailed to 1,965 offices nationwide in 2009. In 2008, 3,558 offices were registered with the National Association for Home-Visit Nursing Care. All offices were allocated a number and chosen by a computer to generate random numbers. The questionnaire was evaluated for recovery rate and inappropriate answer in advance by pilot study targeting 200 offices. The questionnaire was mainly a selection formula. The choices were created with reference to previous studies [7, 8]. Data from the collected questionnaires were inputted by a person and provided to the subjects of the study. Statistical data analyses were conducted using SPSS® statistics software. Continuous parameters with normal distribution were analyzed by Student’s t test. Five-point scales with non-normally distributed variables were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test. Binary variables were analyzed by the χ2 test. A two-tailed test was used for all statistical analyses. In all cases, a P value of 0.05 was used as the threshold level of significance.

Results

Basic characteristics of the subjects

Nurses at 1,314 offices replied to the questionnaire, 651 offices did not reply, and 26 offices had closed down. Five offices performed only psychiatric services and thus did not dispose of HMC waste. Analysis of the remaining 1,283 offices was made. Offices were classified by management configuration. Offices attached to hospitals were classified as “attached office” and all others were classified as “independent office” (Table 1). On average, attached offices had been in existence longer than independent offices. In addition, attached offices have fewer part-time nurses and visit patients’ houses less often per month than do independent offices (Table 1). All of these differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Mode of transportation for home visits

The majority of nurses visit home-care patients by automobile, while about 20 % of nurses visit by bicycle. Public transportation was the least utilized mode of transportation. There were significant differences between the attached and independent offices on utilization of public transportation (P < 0.05). Multiple responses were allowed for this question, and hence, totals are greater than 100 % (Table 2).

Waste recovery status and problems

More attached office nurses recovered medical waste from patients’ homes than did independent office nurses (P < 0.001, Table 3). They were also more likely to transport waste with them during the course of a day’s visits. Both attached and independent office nurses were more concerned with potential injury and bad odor from waste than with the physical weight of transported waste (Table 3).

Improvement of HMC waste disposal

Nurses also responded to the five-point scale improvements of HMC waste disposal. There are five terms about HMC waste disposal shown in Fig. 1. Each term was listed in the questionnaire with reference to previous studies [7, 8] and nurses chose the answer in the form of a five-point scale. Higher score indicates that nurses need to improve the problem. Of note is the fact that there was a significant difference between attached and independent offices in the burden of expense for waste disposal (P < 0.05, Fig. 1).

Discussion

The present study outlines the current status of HMC waste recovery and identifies the most pressing problems encountered by home-visit nurses. Many visiting nurses have to recover HMC waste from patients’ houses and return it to their offices for disposal. In this study, 86.4 % of nurses working at attached and 71.1 % of nurses working at independent offices (79.3 % of nurses in total) transport HMC waste from patients’ houses to their offices. Because of differences in the amount of logistical barriers, nurses working at attached offices recover HMC waste and deliver it to their hospitals more easily than do nurses working at independent offices. Thus, the waste recovery rate was higher for attached offices. The waste recovery rate was higher than the previous study [5], which found that 61.2 % of home-visit nursing stations recover HMC waste. Some HMC waste is not infectious such as dialysis bags, tubes, and plastic bottles. It is appropriate that these non-infectious wastes are being treated as municipal solid waste. In this regard, some Japanese municipalities provide a guide to be treated as municipal solid waste to these non-infectious wastes [11, 12]. However, some home patients do not want to treat this waste as municipal solid waste, because they do not wish their disease to be known to others. Such non infectious HMC wastes were collected by nurses. Some home patients also take these wastes to their doctors. Education to home patients is also an important issue. Home care is increasing every year and is a viable alternative to hospitalization for many patients. Fundamental reform is needed.

Another problem is that the systematic education about specially controlled municipal solid waste is needed for municipal workers. Because of the law, municipalities are responsible for disposing specially controlled municipal solid waste which includes HMC waste. However, municipal workers have had a difficult time keeping abreast of the medical knowledge required for the proper handling of HMC waste [6]. Thus, it would seem that placing a greater burden for waste recovery on trained medical professionals is not unwarranted. Even then, a recent study showed 66 % of municipalities recovers HMC waste as a municipal solid waste [7]. Waste recovery seems to proceed slowly in Japanese municipalities. In this vein, the World Health Organization and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have already established strict guidelines for the management of infectious waste from medical institutions [13–16]. It is time for the Japanese government to address HMC waste disposal more comprehensively through necessary legislation and standardization. In this respect, the Japanese Ministry of Environment launched the guideline for HMC waste disposal finally [17].

To help lay the foundation for future action on HMC waste carrying, this study identified several key characteristics of HMC waste carrying by home-visit nurses. First, 49.7 % of nurses working at attached offices and 39.7 % of nurses working at independent offices must carry waste with them after their first home visit on a given day. In addition, they also worry about bad odor, especially because automobiles are the most commonly used means of transportation for home visits as they are useful in carrying multiple items and supplies. The Japanese government should help facilitate carrying of HMC waste by subsidizing the compartmentalization of the automobiles used by home-visit nurses to help control odor problems and alleviate fears of contamination. On the other hand, because about 30 % of home-visit nurses use bicycles and there are many narrow roads in Japan, especially in urban areas, small storage and transport devices for waste that are suitable for bicycle visits are also needed.

Nurses from independent offices stated that they felt a greater burden of expense for waste disposal than did attached office nurses. Previous study showed that 57.5 % of home-visit nursing stations cited the expense of waste management as an important problem [5]. Attached office nurses do not have to consider the cost of waste disposal as acutely as do independent office nurses because their mother hospitals will bear the cost. In Japan, the cost of medical waste disposal is very high compared to the cost of industrial waste. The Japanese government should consider subsidizing HMC waste disposal by independent offices.

The present study had several advantages over previous studies [5–10] with respect to study design. First, data were collected from a larger nationwide sample of home-visit nursing stations. In this study, 1,283 nursing offices were served as the subjects, which were 36.1 % of the registered in the National Association for Home-Visit Nursing Care, and 23.6 % of Japanese Home-Visit Nursing stations [1]. In addition, there were no statistical differences in the percentage of management configuration between the subjects of this study and Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare statistics [1]. Second, despite the nationwide survey, the response rate of this study was 66.9 %. This was a good response rate. However, its limitations must not be overlooked. First, because the subjects surveyed were only home-visit nursing stations, no conclusions can be drawn about any other services involved with HMC waste disposal, such as municipalities, other waste disposers, and medical institutions. Second, the current study does not adequately address the disparate situations faced by nurses in a variety of regional and management configurations. These additional questions and considerations, among others, should be the focus of future studies.

Conclusions

Domestic medical waste is a constant concern and growing problem with HMC. Home-visit nurses felt a great burden of HMC waste management. It is time for the Japanese government to address HMC waste disposal more comprehensively through necessary legislation, subsidization, and standardization.

References

Japan ministry of health labor and welfare statistics (2009) Summary of survey results nursing care facilities business (in Japanese). http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/24-20-2.html. Accessed 6 April 2012

Japan ministry of the Environment (2001) Japanese waste disposal and public cleansing law. No. 66 of 2001. http://www.env.go.jp/en/laws/. Accessed 4 April 2012

Miyazaki M, Une H (2005) Infectious waste management in Japan: a revised regulation and a management process in medical institutions. Waste Manag 25:616–621

Japan Ministry of the Environment (2005) Study report on the home health care waste handling (in Japanese)

Miyazaki M et al (2007) The treatment of infectious waste arising from home health and medical care services: present situation in Japan. Waste Manag 27(1):130–134

Harada M (2007) Municipalities activity support on medical waste (in Japanese). Yugai iryohaikibutu kenkyu 20(1):3–11

Yano H, Shirai M, Ishiguro C, Mori H, Hirai E, Sasaki N, Hirose Y, Matsushima H (2008) Education support for home care and proper disposal of waste in home-visit nursing station (in Japanese). Iryohaikibutu kenkyu 15(1):17–31

Sugihara K, Tayama T, Nishimura K, Ohta S (2009) Survey and collection and disposal of home medical waste in Hiroshima Prefecture (in Japanese). Yugai iryohaikibutu kenkyu 21(1):78–84

Hirai E, Muraoka R, Nozawa A, Yano H, Kodama K, Matsushima H (2001) Current status and issues on the handling of medical waste in-home visit nursing care stations in Shizuoka Prefecture (in Japanese). Iryohaikibutu kenkyu 14(1):27–37

Harada M (2011) The points of appropriate treatment for home medical care waste (in Japanese). Yugai iryohaikibutu kenkyu 23(2):78–84

City of Sapporo. Gomi-bunbetu-jiten (in Japanese). http://www.city.sapporo.jp/seiso/bunbetsu/index.html. Accessed 6 April 2012

City of Nagoya. How to dispose of medical waste arising from the home (in Japanese). http://www.city.nagoya.jp/kurashi/category/5-4-6-3-0-0-0-0-0-0.html. Accessed 6 April 2012

World Health Organization, regional office for western pacific and for south-east pacific (2004) Practical guidelines for infection control in health care facilities. Reference available from http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/emergencies/infcontrol/en/. Accessed 6 April 2012

Environmental Protection Agency (1986). EPA guide for infectious waste management. Environmental Protection Agency. Reference available from: http://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=2000E1HP.txt. Accessed 6 April 2012

Landrum VJ, Barton RG (1991) Medical waste management and disposal. Pollution technology review no 200. William Andrew Publishing, Norwich

Department of Health/Finance and Investment Directoratge/Estatesand Facilities Division (2006) Health technical memorandum 07-01: safe management of healthcare waste. Department of Health/Finance and Investment Directoratge/Estatesand Facilities Division, Quarry House Leeds LS2 7UE. Reference available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_063274. Accessed 6 April 2012

Japan Ministry of the Environment (2011) The guideline for home medical care waste management and disposal (in Japanese). Reference available form: http://www.env.go.jp/recycle/misc/guideline.html. Accessed 6 April 2012

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Japan Ministry of the Environment (grant-in-aid for scientific research to promote a recycling-oriented society 08065604, 2008–2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ikeda, Y. Current status of waste management at home-visit nursing stations and during home visits in Japan. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 14, 202–205 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-012-0058-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-012-0058-9