Abstract

Intracerebral arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are traditionally recognized as congenital lesions. However, with the advent of frequent, noninvasive imaging of the brain, that notion has been challenged. We describe another patient with a de novo cerebral arteriovenous malformation and evaluate the reported literature for trends in the development of these lesions. Cases were selected from the English literature using the PUBMED database using the search term “acquired or de novo cerebrovascular arteriovenous malformations”. A total of seven patients (including the one reported in this study) with de novo arteriovenous malformations are reported. Majority of patients were female, and mostly diagnosed as children. Their mean age at diagnosis was 18 years (6–32), and the mean time from the initial intracranial study to the diagnosis of an AVM was 8 years (3–17). De novo formation of AVMs is being increasingly reported, especially in young females. We present only the seventh such case reported in the literature and challenge the traditional view that all arteriovenous malformations are congenital in nature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intracerebral arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are caused by defects in the development of blood vessels and are characterized by an arteriovenous shunt without a capillary bed, but with the presence of an arterial nidus [4, 7]. AVMs were traditionally thought to be congenital in origin, but several recent de novo cases challenge this notion [3, 4, 7, 15]. However, the pathogenesis of AVMs is not completely understood, and many AVMs have been shown to progress as well as undergo spontaneous regression [6]. We present a patient with a de novo AVM that was found incidentally 14 years after being diagnosed with Bell’s palsy on the same side. We review this case in the context of others reported in the literature looking for common patient trends in the formation of de novo AVMs.

Case report

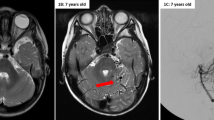

At the age of 16, the patient was diagnosed with Bell’s palsy. Her magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans from 1995 revealed no vascular abnormality, abnormal signal intensity, or any other suggestion of an arteriovenous malformation (Fig. 1).

Fourteen years later, the patient presented with a 5-year history of complicated migraines, which were at times associated with right-sided facial weakness. Two to three weeks prior to diagnosis, she had an episode where she could not speak, which lasted for about 10 to 15 min. This episode of speech arrest was likely a seizure. In order to determine the cause of her migraines and seizure, intracranial imaging was performed. Her post-contrast computed tomography (CT) and MRI revealed a left frontoparietal arteriovenous malformation (Fig. 2). She then underwent bilateral carotid angiography, and the presence of the AVM was confirmed in her left frontoparietal region (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Once thought of as static lesions, AVMs are now becoming more accepted as being dynamic lesions. To our knowledge, there have been six previously reported cases of de novo AVM formation [3, 4, 7, 11, 13, 15]. We present the seventh reported case of a de novo AVM and the first reported case occurring in a patient with a history of Bell’s palsy.

Histopathologically, AVMs are characterized by vessels with thin or irregular muscularis and elastica, endothelial thickening, and media hypertrophy in the nidus [5]. These lesions are typically thought to be congenital in nature, arising around the 28th day of intrauterine life [7], and are thought to be caused by a defect in primordial capillary or venous formation [6]. Nonetheless, very few cases are detected in utero or in children [15], in comparison to the vast majority of diagnoses made during adulthood [5, 15].

However, the dynamic nature of cerebral AVMs is attested to by multiple recent case reports demonstrating spontaneous progression and resolution [2, 6, 8]. Of the six previous cases of de novo AVM formation, four were reported in children (Table 1). Three of the four children had etiologies that may have contributed to the formation of the AVM (Table 2). The fourth child developed a de novo AVM after suffering trauma to the head.

In addition, six of the seven reported cases of de novo AVMs, including our patient, were found in females. On average, these lesions developed 8 years (3–17) after initial imaging, with a mean age at diagnosis of approximately 18 years (6–32). In contrast, the mean age of patients diagnosed with congenital AVMs is 33 years [10]. Hence, the initial inflammatory or ischemic insult occurring in these patients could potentially have accelerated the development of the de novo AVM in comparison to the growth of congenital AVMs.

Critics argue that these reported cases of de novo AVMs may be attributed to the lack of sensitivity and specificity of imaging techniques, specifically angiography, and that de novo AVMs may be due to the growth of a previously small but occult AVM [7]. Angiography may fail to demonstrate arteriovenous shunting due to partial or complete thrombosis, previous hemorrhage, or adjacent edema [7]. However, most reported cases of de novo AVMs have been in the last decade, during which time the availability of high-resolution, serial cross-sectional imaging has made it possible to detect lesions that were once thought to be occult.

In our patient, the lesion developed 14 years after the initial MRI and CTA study. These initial scans revealed no vascular abnormality or abnormal signal intensity (Fig. 1). Subsequent imaging revealed lesions specific enough for the diagnosis of a de novo AVM (Figs. 2 and 3).

This case may represent the third instance in which an inflammatory insult led to the formation of an AVM [4, 13]. Several studies have shown that vascular endothelial growth factor may be the key link between the initial inflammatory injury and the growth of the AVM [9, 12, 14–17].

Recently, isolation and characterization of circulating endothelial cells from hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia patients has revealed a decreased expression of endoglin, impaired activin receptor-like kinase-1 (ALK-1), and ALK-5 dependent transforming growth factor-β signaling, disorganized cytoskeleton, and a failure to form cord-like structures, which may lead to fragile, small blood vessels or abnormal angiogenesis after injuries [1].

Whether similar abnormalities exist in some patients that contribute to abnormal repair processes following injury, and lead to some of these acquired arteriovenous malformations, is a provocative hypothesis.

In conclusion, this case represents only the seventh reported case of a de novo AVM, and adds to the growing body of evidence challenging the traditional view that all AVMs are congenital in nature. Acquired AVMs may be more common than traditionally believed, and it is clear that a more thorough understanding of the pathogenesis of AVMs is needed to better understand their development.

References

Abdalla SA, Letarte M (2006) Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: current views on genetics and mechanisms of disease. J Med Genet 43:97–110

Abdulrauf SI, Malik GM, Awad IA (1999) Spontaneous angiographic obliteration of cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery 44:280–289

Akimoto H, Komatsu K, Kubota Y (2003) Symptomatic de novo arteriovenous malformation appearing 17 years after the resection of two other arteriovenous malformations in childhood: case report. Neurosurgery 52(1):228–232

Bulsara KR, Alexander MJ, Villavicencio AT, Graffagnino C (2002) De novo cerebral arteriovenous malformation: case report. Neurosurgery 50(5):1137–1141

Choi JH, Mohr JP (2005) Brain arteriovenous malformations in adults. Lancet Neurology 4:299–308

DeCesare B, Omojola MF, Fogarty EF, Brown JC, Taylon C (2006) Spontaneous thrombosis of congenital cerebral arteriovenous malformation complicated by subdural collection: in utero detection with disappearance in infancy. Br J Radiol 79:e140–144e

Gonzalez LF, Bristol RE, Porter RW, Spetzler RF (2005) De novo presentation of an arteriovenous malformation. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 102(4):726–729

Hamada J, Yonekawa Y (1994) Spontaneous disappearance of a cerebral arteriovenous malformation: case report. Neurosurgery 34:171–173

Kilic T, Pamir MN, Küllü S, Eren F, Ozek MM, Black PM (2000) Expression of structural proteins and angiogenic factors in cerebrovascular anomalies. Neurosurgery 46(5):1179–1192

Ondra SL, Troupp H, George ED, Schwab K (1990) The natural history of symptomatic arteriovenous malformations of the brain: a 24-year follow-up assessment. J Neurosurg 73:387–391

O’Shaughnessy BA, DiPatri AJ Jr, Parkinson RJ, Batjer HH (2005) Development of a de novo cerebral arteriovenous malformation in a child with sickle cell disease and moyamoya arteriopathy. Case report. J Neurosurg 102(2 Suppl):238–243

Sandalcioglu E, Wende D, Eggert A, Müller D, Roggenbuck U, Gasser T, Wiedemayer H, Stolke D (2006) Vascular endothelial growth factor plasma levels are significantly elevated in patients with cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Cerebrovascular Diseases 21:154–158

Schmit BP, Burrows PE, Kuban K, Goumnerova L, Scottt RM (1996) Acquired cerebral arteriovenous malformation in a child with moyamoya disease. Case report. J Neurosurg 84(4):677–80

Sonstein WJ, Kader A, Michelsen WJ, Llena JF, Hirano A, Casper D (1996) Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in pediatric and adult arteriovenous malformations: an immunocytochemical study. J Neurosurg 85:838–845

Stevens J, Leach JL, Abruzzo T, Jones BV (2009) De novo cerebral arteriovenous malformation: case report and literature review. American Journal of Neuroradiology 30(1):111–112

Sure U, Butz N, Schlegel J, Siegel AM, Wakat JP, Mennel HD, Bien S, Bertalanffy H (2001) Endothelial proliferation, neoangiogenesis, and potential de novo generation of cerebrovascular malformations. J Neurosurg 94:972–977

Sure U, Battenberg E, Dempfle A, Tirakotai W, Bien S, Bertalanffy H (2004) Hypoxia-inducible factor and vascular endothelial growth factor are expressed more frequently in embolized than in nonembolized cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery 55(31):663–670

Disclosures

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Comments

Ulrich Sure, Essen, Germany

Mahajan et al. contribute another case of a de novo arteriovenous malformation (AVM). Their case is very well documented and nicely illustrated. It is the seventh case in literature, and it is noteworthy that four of these previously reported individuals were children.

The authors eloquently discuss the assumption that AVMs might not be congenital rather than acquired lesions. Their biology might well be dynamic, which has been shown in a number of clinical and clinicopathological reports. It remains questionable whether the pathobiology of the actual case (similarly as two previously reported cases) might be attributed to inflammatory insult as the authors discuss.

Discussing about the possible biology and embryology of AVMs should always include the quotation of a highly interesting question that was first discussed in the excellent review of Sean Mullan et al. (1) in 1996: “Why does the intrauterine and neonatal ultrasound fail to monitor pial AVMs?”... although it frequently diagnoses vein of Galen malformations, whose incidence should be definitely rarer than the incidence of pial AVMs.

Thus, in my eyes, it is important to report on cases of de novo AVMs in order to shift our neurosurgeons’ understanding of the biology of AVMs toward a new paradigm: “AVMs should not be considered as congenital pathologies”.

Reference

1. Mullan S, Mojtahedi S, Johnson DL, Macdonald RL (1996) Embryological basis of some aspects of cerebral vascular fistulas and malformations. J Neurosurg 85:1–8

Anton Valavanis, Gerasimos Baltsavias, Zürich, Switzerland

This case report presents the case of a brain AVM that was detected in a patient many years after a previous MRI did not show such a vascular abnormality. The case is interesting because it further corroborates the concept that cerebral arteriovenous shunts, representing an heterogeneous group of vascular lesions, constitute the manifestation of a complex process between several interacting components such as a causative trigger (genetic and/or environmental factors that produce a permanent change to the), a target (artery or vein), a revealing trigger (various mechanical, hormonal, pharmaceutical, hemodynamic, thermal, infectious, metabolic factors, or radiation that reveal the underlying, not yet expressed change), and the timing (early or late effect and expression) in the course of the ongoing vascular remodeling (1). Since “congenital” means dating from birth, it refers to the component of time and ignores the issue of whether an underlying latent flaw was present at birth but not expressed yet as a visible morphological alteration. Therefore, the so-called traditional view that brain AVMs are congenital has been certainly challenged since many years as a result of important evidence; but, this is only related to their morphological identification and not to a potential quiescent and otherwise congenital defect.

Two distinct entities that apparently result from a prenatal revealing trigger are the vein of Galen aneurysmal malformations that develop during embryonic period and dural sinus malformations that occur during the fetal period. The pial arteriovenous shunts most likely are presented as a result of a perinatal revealing trigger. Most other intracranial AV lesions, including brain AVMs, develop in the postnatal period and most likely after infancy and adolescence.

Reference

1. Lasjaunias P, ter Brugge KG, Berenstein A (2006) Surgical neuroangiography 3, clinical and interventional aspects in children. Second edition. Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 93–104

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mahajan, A., Manchandia, T.C., Gould, G. et al. De novo arteriovenous malformations: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev 33, 115–119 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-009-0227-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-009-0227-z