Abstract

In our emergency department (ED), patients with flank pain often undergo non-enhanced computed tomography (NECT) to assess for nephroureteral (NU) stone. After immediate image review, decision is made regarding need for subsequent contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) to help assess for other causes of pain. This study aimed to review the experience of a single institution with this protocol and to assess the utility of CECT. Over a 6 month period, we performed a retrospective analysis on ED patients presenting with flank pain undergoing CT for a clinical diagnosis of nephroureterolithiasis. Patients initially underwent abdominopelvic NECT. The interpreting radiologist immediately decided whether to obtain a CECT to evaluate for another etiology of pain. Medical records, CT reports and images, and 7-day ED return were reviewed. CT diagnoses on NECT and CECT were compared. Additional information from CECT and changes in management as documented in the patient’s medical record were noted. Three hundred twenty-two patients underwent NECT for obstructing NU stones during the study period. Renal or ureteral calculi were detected in 143/322 (44.4 %). One hundred fifty-four patients (47.8 %) underwent CECT. CECT added information in 17/322 cases (5.3 %) but only changed management in 6/322 patients (1.9 %). In four of these patients with final diagnosis of renal infarct, splenic infarct, pyelonephritis and early acute appendicitis in a thin patient, there was no abnormality on the NECT (4/322 patients, 1.2 %). In the remaining 2 patients, an abnormality was visible on the NECT. In patients presenting with flank pain with a clinical suspicion of nephroureterolithiasis, CECT may not be indicated. While CECT provided better delineation of an abnormality in 5.3 % of cases, changes in management after CECT occurred only in 2 %. This included 1 % of patients in whom a diagnosis of organ infarct, pyelonephritis or acute appendicitis in a thin patient could only be made on CECT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Non-enhanced computed tomography (NECT) is the test of choice to evaluate suspected renal colic as an etiology of flank pain [1, 2]. NECT is rapid and accurate, allows identification of the stone location and size, facilitates triage of patients, and has a 98–100 % sensitivity and 92–100 % specificity for the detection of renal and ureteral calculi [3–9]. Because flank pain is a nonspecific symptom, with possible alternate diagnoses in the absence of nephroureterolithiasis, in our practice, patients with flank pain often undergo a CECT following abdominopelvic (AP) NECT if no stone is seen on NECT. We adapted this practice in 2002 at the request of the emergency medical and surgical teams to evaluate for alternative causes of flank pain. However, many extra-urinary etiologies of flank pain, such diverticulitis, adnexal mass, appendicitis or neoplasm, can be identified on NECT [10–12]. Additionally, as attention to radiation dose and increasing concern for radiation induced cancer rises, the necessity of an additional scan should be critically evaluated [13, 14]. The purpose of this study is to review the experience of a single institution with this protocol and to assess the utility of follow-up CECT after initial NECT.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective quality assurance evaluation of our ED CT protocol for patients presenting with flank pain. This single center study was conducted in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and reviewed by the hospital institutional review board. Informed consent was waived due to retrospective study design and quality assurance aim. The study was performed at an urban level I trauma tertiary referral center with approximately 53,000 ED visits per year. Essentially, all ED visits are adult patients given the proximity of a pediatric ED to our site.

NECT examinations were performed on a 64 MDCT GE LightSpeed VCT scanner (Light Speed, General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). Five millimeter spiral NECT axial images were obtained from the diaphragm to the lesser trochanter with a table speed of 55 mm/rotation, rotation speed of 0.5 s, 1.375 pitch, 120 kV, noise index 30, and mA range 200–600. Coronal and sagittal reformations were provided. If IV contrast was administered, CECT was obtained using the same parameters, with a split bolus technique, which is routinely applied at our institution for non-angiographic CT studies to obtain both the excretory and nephrographic phases simultaneously. A 50-cc IV contrast bolus was administered for the excretory phase, and 3 min thereafter, 80 cc of IV contrast was provided for the nephrographic phase. The CECT was triggered off of normal appearing liver parenchyma. CT imaging was reviewed on a GE Centricity Picture Archiving and Communications System (PACS) workstation.

Per our CT ED protocol, patients presenting with flank pain or clinical concern for nephroureterolithiasis underwent NECT with the above parameters. While the patient was still on the CT table, the radiologist reviewed the images in PACS and determined if a renal or ureteral stone was present and whether to administer IV contrast to evaluate for alternative diagnosis or additional findings. Department ED protocol has historically been that typically no additional imaging is needed if an obstructing renal or ureteral stone is seen on the NECT.

We performed retrospective analysis on all ED patients who underwent NECT of the abdomen and pelvis during a 6-month period (July 1, 2010–December 31, 2010. Final radiology reports, medical records, and 7-day ED return were retrospectively reviewed. CT images where reviewed only when a diagnosis other than obstructing renal stone was made after CECT. These cases were reviewed on a PACS workstation by a radiologist (B.S.) blinded to the final diagnosis who was asked to provide a diagnosis on NECT. After unblinding to the final diagnosis, three radiologists (M.D.A., R.B.L., B.S.) in consensus graded the impact of CECT on making the diagnosis (no additional information, better delineation of the abnormality, finding only visible on CECT). The impact on management of any additional information provided from CECT was determined by review of the medical records.

Data collected included patient demographics, presenting symptoms, serum creatinine, CT examination protocol, and acute CT findings per the final radiology report at the time of initial study interpretation. The following CT findings were evaluated: presence or absence of stone and location, hydronephrosis, perinephric stranding, renal mass, and acute non-NU findings as explanation of pain. Presence or absence of additional findings on CECT was noted and correlated with medical record review as to whether these findings engendered a change in management. If a final CT read reported an “equivocal stone,” we reviewed the medical record to determine if the patient was treated for stone disease or alternate cause of pain. In order to establish whether a diagnosis was missed on initial NECT, we reviewed medical records and PACS records for a return visit to the ED within 7 days with a similar complaint or hospital admission and any additional imaging.

Results

Search of our database revealed 411 patients who underwent NECT over the study period. Eighty-nine studies were excluded, and final analysis was performed on 322 patients. Exclusion criteria are summarized in Fig. 1 and consisted of the following: an indication of generalized abdominal pain (n = 4), history of renal transplant (n = 2), painless hematuria (n = 1), patient could not receive IV contrast due to prior contrast reaction (n = 14), refusal to receive contrast (n = 3), or renal insufficiency (n = 46). Studies performed for further evaluation of known findings on prior imaging or after a recent urological procedure were also excluded (n = 8). We excluded studies if the NECT was performed at a lower mA (mA range 60–200) as our ED protocol specifies a mA range of 200–600 (n = 11). Patients who were unable to tolerate the prone position, as well as patients with inflammatory bowel disease who received oral contrast in whom there was concern for NU stone were included in the study. Thus, a total of 322 patients were included in our final analysis, with an age range of 18–94 years (mean age, 46 years). One hundred thirty-three (41 %) were male and 189 (59 %) were female. The most common presenting symptoms were flank pain, lower quadrant pain, and back pain. The results are summarized in Fig. 2.

Patients undergoing AP NECT in our ED during a 6-month period. a Patients with a NU stone. “Additional acute finding” refers to an acute finding in addition to a NU stone per the final radiology report at the time of study interpretation. b Patients without a NU stone. NECT non-enhanced computed tomography, CECT contrast-enhanced computed tomography

Patients with NU stones

NU stones were detected in 143 of 322 patients (44.4 %) (Fig. 2a). In all patients, the stone was noted on the side of the patient’s symptoms and was non-obstructing in 25 of 40 patients (62.5 %) but was obstructing in 15 of 40 (37.5 %). Forty of 143 patients (28.0 %) subsequently received IV contrast. There is no documentation of the reason for IV contrast administration, and CECT did not provide additional information.

In 1/103 (0.97 %) patient with a NU stone who did not receive contrast, there was an additional finding of possible early acute cholecystitis on CT. The patient underwent surgery for an inflamed gallbladder with a postoperative diagnosis of acute on chronic gallbladder inflammation.

Patients without NU stones

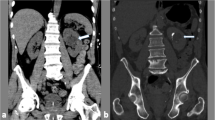

One hundred seventy-nine patients did not have a NU stone (Fig. 2b). IV contrast was administered to 114 (63.7 %) of these patients. Of these, 28 had acute findings summarized in Table 1. Diagnoses related to the kidneys and urinary tract included cystitis (n = 2), pyelonephritis (n = 3), renal infarct (n = 2), Foley catheter in prostatic urethra (n = 1), and alternative diagnoses included diverticulitis (n = 6), appendicitis (n = 2), pancreatitis (n = 1), splenic infarct (n = 1), and epiploic appendagitis (n = 2). IV contrast added information in 17 of the 28 cases (5.3 % of total 322 cases) but only changed management in 6 cases (1.9 % of total 322 cases) (Table 1). In 4 patients (1.2 % of total 322 cases), an abnormality was only seen on CECT (splenic and renal infarct (n = 2), pyelonephritis (n = 1), early acute appendicitis (n = 1)) (Fig. 3).

Of the 65 patients who did not have a stone and did not receive contrast, 7 had acute findings on NECT and 58 did not. The non-NU findings included 3 patients with diverticulitis, all clearly delineated on NECT without evidence of complication (Fig. 4); and one patient with a hemorrhagic corpus luteum, which was on the same side as the patient’s pain and also seen on a pelvic ultrasound performed 3 h prior to the CT. Acute urinary tract findings included possible pyelonephritis (n = 2) and possible recent stone passage (n = 1). In this last patient, CT showed mild left hydronephrosis and hydroureter without a stone identified, suggesting recent stone passage, and mild bilateral perinephric stranding. The patient was treated for both passed stone and pyelonephritis by the ED team.

Of the 58 patients who did not have a stone and did not have acute CT findings on NECT to explain symptoms, 6 patients returned to our institution’s ED within 7 days. One patient returned to the ED within 24 h with worsening pain and was subsequently found to have a stone on the CECT when the prior NECT was negative, due to progressive right hydroureteronephrosis and new right perinephric fluid on CECT. Following the positive CECT, the patient was discharged from the ED with pain medication, Flomax, and instructions for oral hydration. In a second patient, the NECT was negative, but the patient returned with worsening pain and was admitted for pyelonephritis without CECT imaging. A third patient underwent a negative NECT and following an episode of hypotension in the setting of urinary tract infection, underwent a CECT, which was also negative. Three patients with back and body pain with negative NECTs were discharged and returned within 2 days. None of the three had further imaging in the ED; however, one had an outpatient MRI, which confirmed the clinical suspicion of lumbar degenerative disease as etiology of back pain. Six of the 58 patients were admitted to the hospital. None of these patients underwent additional imaging during the admission that changed the initial CT diagnoses.

Discussion

In this article, we review our experience with our CT protocol through which patients with concern for nephroureterolithiasis versus other acute cause of flank pain initially undergo a NECT. After immediate image review while the patient is still on the CT scanner, the decision is made regarding need for IV contrast to help assess for other causes of pain. Our goal was to assess if the CECT is necessary for detection of additional findings or if it may be eliminated in the emergency setting. We conclude that CECT is unlikely to reveal additional acute findings not seen on NECT. CECT added additional information in 5.3 % and helped to further delineate an abnormality and assess for complications identifying the following: a small abscess in diverticulitis, striated nephrogram in pyelonephritis, bowel wall thickening in enteritis, wall hyperemia in colitis and Crohn’s, and excluding wall ischemia in a small bowel obstruction. However, a change in management was only observed in 1.9 % of cases. This includes 1.2 % of cases where abnormalities were only seen on CECT due to solid organ infarcts, pyelonephritis, and early acute appendicitis in a thin patient. Miller and colleagues reported similar findings in patients with acute renal colic and concluded that IV contrast is rarely helpful in this setting [15]. However, acute renal infarction in the ED has a reported incidence of 7 in 100,000 and is frequently missed unless there is a high degree of clinical suspicion [16]. In our study, a renal infarct was identified in only 2/322 patients (0.6 %).

Thus, as outlined in the guidelines set forth by the ACR Appropriateness Criteria ® for patients with acute onset flank pain and suspicion of stone disease, NECT is the study of choice for evaluation of suspicion of stone disease as well as evaluation of patients with recurrent symptoms of stone disease. While CECT may be appropriate if the NECT demonstrates abnormalities that should be further assessed with contrast [3], our data suggest that CECT adds information in only 5 % of cases resulting in a change in management in only 2 %. This includes 1 % of patients where CECT reveals a diagnosis unsuspected on NECT.

A limitation of our study is its retrospective design. There was no documentation regarding the decision to administer IV contrast. Twenty-eight percent of patients with a NU stone, 38 % of whom had an obstructing stone, still received IV contrast. One possibility is that the interpreting radiologist saw something else on the NECT that he/she determined needed additional work up, but was normal on the CECT. Alternatively, the radiologist may have given IV contrast in order to distinguish a ureteral stone from a phlebolith or arterial vascular calcification [15]. Radiologists may have given IV contrast if the side of the stone did not correspond to the side of the patient’s pain. These limitations affect generalizability as in many institutions; only NECT is performed when a stone is seen. Additionally, since the patient remains on the CT table as the radiologist checks the NECT images, there is a time limitation during which the images are reviewed. Unless a thorough review of the case is performed before the decision to give contrast, including comparison to prior imaging, there may be findings that the radiologist feels warrant further evaluation, but may have actually been stable from prior studies without the radiologist’s immediate knowledge. Finally, at our institution, radiology residents take independent call between 11 pm–8 am daily. While on independent call, a resident checking the NECT may not feel confident regarding how the readout attending would proceed and may choose to obtain the CECT to ensure all necessary images are acquired. While the practice of performing CECT after NECT increased the sensitivity for alternative findings and complications, management only changed in 2 % of patients, at the expense of greater exposure to radiation and to IV contrast.

Only 6 of 58 patients with a normal NECT returned to our ED within 7 days. However, it is possible that some patients may have presented to another institution, limiting our follow-up of these patients. Five of six patients with negative NECT did not have further imaging at the second ED visit or had a negative CECT. One patient had a ureteral stone seen on subsequent CECT due to increased ureteral edema and perinephric fluid. The patient was discharged from the ED with pain medication, Flomax, and instructions for oral hydration.

Eliminating CECT in patients with flank pain has implications for dose reduction. A future direction includes analyzing the doses of both phases to quantify to what extent eliminating the second phase decreases radiation exposure to patients. In two studies, one by Poletti et al. performed in ED patients and one by Kim et al. which did not specify an ED population, low-dose CT achieved sensitivities and specificities similar to those of standard-dose CT in assessing the diagnosis of renal colic, depicting ureteral calculi >2–3 mm and identifying alternate etiologies of patient’s symptoms [17, 18]. Future studies may be directed toward decreasing the dose of the NECT in the ED in our institution.

Dual-energy computed tomography is being evaluated for detection of renal or ureteral calculi in a contrast filled collecting system using iodine subtraction techniques. It may also allow for characterization of stone composition, which has clinical implications for management [19, 20]. Dual energy CT may decrease patient’s overall radiation exposure by eliminating the NECT. However, in one study, while large (at least 2.9 mm) and high-attenuation (387 HU) calculi were detected with dual-energy CT, smaller and lower attenuation calculi were more frequently missed, especially with increased image noise [21]. As dual energy techniques are still being developed, NECT currently remains the mainstay for detection of NU calculi.

In conclusion, CECT may not be indicated in patients presenting with flank pain with clinical suspicion of nephroureterolithiasis. While CECT provided better delineation of an abnormality seen on NECT and revealed additional information in 5 % of cases, changes in management after CECT occurred in only 2 %. This included 1 % of patients in whom a diagnosis of organ infarct, pyelonephritis or acute appendicitis in a thin patient which could only be made on CECT.

References

Westphalen AC, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Wang R, Gonzales R (2011) Radiological imaging of patients with suspected urinary tract stones: national trends, diagnoses, and predictors. Acad Emerg Med 18(7):699–707

Reddy S (2008) State of the art trends in imaging renal of colic. Emerg Radiol 15(4):217–225

Coursey CA, Casalino DD, Remer EM, Arellano RS, Bishoff JT, Dighe M, Fulgham P, Goldfarb S, Israel GM, Lazarus E, Leyendecker JR, Majd M, Nikolaidis P, Papanicolaou N, Prasad S, Ramchandani P, Sheth S, Vikram R (2011) Expert Panel on Urologic Imaging. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® acute onset flank pain — suspicion of stone disease. Reston (VA): American College of Radiology (ACR) p 7 [70 references]

Smith RC, Rosenfield AT, Choe KA, Essenmacher KR, Verga M, Glickman MG, Lange RC (1995) Acute flank pain: comparison of noncontrast enhanced CT and intravenous urography. Radiology 194(3):789–794

Smith RC, Verga M, McCarthy S, Rosenfield AT (1996) Diagnosis of acute flank pain: value of unenhanced helical CT. Am J Roentgenol 166(1):97–101

Katz DS, Lane MJ, Sommer FG (1997) Non-contrast spiral CT for patients with suspected renal colic. Eur Radiol 7(5):680–685

Dalrymple NC, Verga M, Anderson KR, Bove P, Covey AM, Rosenfield AT, Smith RC (1998) The value of unenhanced helical computerized tomography in the management of acute flank pain. J Urol 159(3):735–740

Fielding JR, Silverman SG, Rubin GD (1999) Helical CT of the urinary tract. Am J Roentgenol 172(5):1199–1206

Coll DM, Varanelli MJ, Smith RC (2002) Relationship of spontaneous passage of ureteral calculi to stone size and location as revealed by unenhanced helical CT. Am J Roentgenol 178(1):101–103

Katz DS, Scheer M, Lumerman JH, Mellinger BC, Stillman CA, Lane MJ (2000) Alternative or additional diagnoses on unenhanced helical computed tomography for suspected renal colic: experience with 1000 consecutive examinations. Urology 56(1):53–57

Rucker CM, Menias CO, Bhalla S (2004) Mimics of renal colic: alternative diagnoses at unenhanced helical CT. Radiographics 24(Suppl 1):S11–S28

Koroglu M, Wendel JD, Ernst RD, Oto A (2004) Alternative diagnoses to stone disease on unenhanced CT to investigate acute flank pain. Emerg Radiol 10(6):327–333

Costello JE, Cecava ND, Tucker JE, Bau JL (2013) CT radiation dose: current controversies and dose reduction strategies. AJR Am J Roentgenol 201(6):1283–1290

McCollough CH, Primak AN, Braun N, Kofler J, Yu L, Christner J (2009) Strategies for reducing radiation dose in CT. Radiol Clin N Am 47(1):27–40

Miller FH, Kraemer E, Dalal K, Keppke A, Huo E, Hoff FL (2005) Unexplained renal colic: what is the utility of IV contrast? Clin Imaging 29(5):331–336

Baig A, Ciril E, Conteras G, Lenz O, Borra S (2012) Acute renal infarction: an underdiagnosed disorder. J Med Cases 3(3):197–200

Poletti P-A, Platon A, Rutschmann OT, Schmidlin FR, Iselin CE, Becker CD (2007) Low-dose versus standard-dose ct protocol in patients with clinically suspected renal colic. Am J Roentgenol 188(4):927–933

Kim BS, Hwang IK, Choi YW, Namkung S, Kim HC, Hwang WC, Choi KM, Park JK, Han TI, Kang W (2005) Low-dose and standard-dose unenhanced helical computed tomography for the assessment of acute renal colic: prospective comparative study. Acta Radiol 46(7):756–763

Marin D, Boll DT, Mileto A, Nelson RC (2014) State of the art: dual-energy CT of the abdomen. Radiology 271(2):327–342

Aran S, Shaqdan KW, Abujudeh HH (2014) Dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) in emergency radiology: basic principles, techniques, and limitations. Emerg Radiol 21(4):391–405

Mangold S, Thomas C, Fenchel M, Vuust M, Krauss B, Ketelsen D, Tsiflikas I, Claussen CD, Heuschmid M (2012) Virtual nonenhanced dual-energy CT urography with tin-filter technology: determinants of detection of urinary calculi in the renal collecting system. Radiology 264(1):119–125

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Agarwal, M.D., Levenson, R.B., Siewert, B. et al. Limited added utility of performing follow-up contrast-enhanced CT in patients undergoing initial non-enhanced CT for evaluation of flank pain in the emergency department. Emerg Radiol 22, 109–115 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-014-1259-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-014-1259-4