Abstract

Since the publication of the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2007, the securitization of global warming has reached a new level. Numerous public statements and a growing research literature have discussed the potential security risks and conflicts associated with climate change. This article provides an overview of this debate and introduces an assessment framework of climate stress, human security and societal impacts. Key fields of conflict will be addressed, including water stress, land use and food security, natural disasters and environmental migration. A few regional hot spots of climate security will be discussed, such as land-use conflicts in Northern Africa; floods, sea-level rise and human security in Southern Asia; glacier melting and water insecurity in Central Asia and Latin America; water conflicts in the Middle East; climate security in the Mediterranean; and the potential impact on rich countries. Finally, concepts and strategies will be considered to minimize the security risks and move from conflict to cooperation in climate policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In its 2007 Fourth Assessment Report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) addresses serious risks associated with climate change that could undermine the living conditions of people all over the world. Vulnerable systems include water resources, agriculture, forestry, human health, human settlements, energy systems, and the economy. The impacts are specific for each region whereas regions highly dependent on ecosystems services and agricultural output are more sensitive. According to the IPCC, the economic and social costs of extreme weather events will increase, and climate change impacts will “spread from directly impacted areas and sectors to other areas and sectors through extensive and complex linkages.” (IPCC 2007)

It is subject to debate and research as to whether the expected climate impacts will also induce security risks and violent conflicts, and if so to what extent. According to Working Group 2 of the 2007 IPCC Report, conflict is one of several stress factors: “Vulnerable regions face multiple stresses that affect their exposure and sensitivity as well as their capacity to adapt. These stresses arise from, for example, current climate hazards, poverty and unequal access to resources, food insecurity, trends in economic globalization, conflict, and incidence of diseases such as HIV/AIDS.” (IPCC 2007, p. 19). More explicit is the Stern Review: “Climate-related shocks have sparked violent conflict in the past, and conflict is a serious risk in areas such as West Africa, the Nile Basin and Central Asia” (Stern et al. 2006).

For Gilman et al. (2007) climate change “poses unique challenges to U.S. national security and interests”. This understanding has been advanced by the report “National Security and the Threat of Climate Change”, published April 16, 2007 by the CNA Corporation and the Military Advisory Board, a blue-ribbon panel of eleven retired U.S. admirals and generals. According to this study, the effects of global warming could lead to large-scale migrations, increased border tensions, the spread of disease and conflicts over food and water, all of which could directly involve the US military. Climate change is characterized as a “threat multiplier for instability in some of the most volatile regions of the world”. The report recommends that the United States commit “to a stronger national and international role to help stabilize climate change at levels that will avoid significant disruption to global security and stability” (CNA Corporation 2007).

Various scenarios of climate security impacts were compiled by a panel of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, including former CIA director James Woolsey, Nobel laureate Thomas Schelling and other key figures. According to its November 2007 report, climate change “has the potential to be one of the greatest national security challenges that this or any other generation of policy makers is likely to confront.” It could “destabilize virtually every aspect of modern life”, and is likely to breed new conflicts. (Campbell et al. 2007).

A comprehensive assessment of the security risks of climate change has been prepared by the German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU 2007). The report concludes that without resolute counteraction, climate change will overstretch many societies’ adaptive capacities within the coming decades, which could result in destabilization and violence, jeopardizing national and international security. Climate change could also unite the international community to set a course for avoiding dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system by adopting a dynamic and globally coordinated climate policy. If it fails to do so, “climate change will draw ever-deeper lines of division and conflict in international relations, triggering numerous conflicts between and within countries over the distribution of resources, especially water and land, over the management of migration, or over compensation payments ….” (WBGU 2007).

Interest in the climate-security nexus has not only increased among academia and think tanks, but in the public and politics as well. In April 2007, the UN Security Council held its first debate on the impact of climate change on peace and security (UNSC 2007), and UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon warned that climate change may pose as much of a danger to the world as war (BBC 2007). With its 2007 peace award to Al Gore and the IPCC, the Nobel Prize Committee shared the view that extensive climate change “may induce large-scale migration and lead to greater competition for the earth’s resources” and result in “increased danger of violent conflicts and wars, within and between states.” (Nobel 2007) A joint report by the European Commission and the High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy concluded that climate change is already having profound consequences for international security that directly affect European interests: “Climate change is best viewed as a threat multiplier which exacerbates existing trends, tensions and instability.” (European Commission 2008) In September 2009, the UN Secretary General published a report on the potential security implications of climate change. Here, the term “threat multiplier” is defined as “exacerbating threats caused by persistent poverty, weak institutions for resource management and conflict resolution, fault lines and a history of mistrust between communities and nations, and inadequate access to information or resources” (UNGA 2009, p. 2).

Contrary to the increasing attention, the research literature does not provide sufficient evidence to support a clear causal relationship between climate impacts, security and conflict. The issue is complex and covers highly uncertain future developments. Potential relationships were discussed in the earlier literature (Gleick 1989; Brown 1989; Scheffran and Jathe 1996; Swart 1996; Van Ireland et al. 1996; Scheffran 1997; Edwards 1999; Rahman 1999), with mixed results. Since the 2007 IPCC report, the number of publications increased significantly, indicating a growing interest in the debate on the securitization of climate change (e.g., Brown 2007; Smith and Vivekananda 2007; Brauch 2009; Brzoska 2009; Carius et al. 2008; Scheffran 2009; Webersik 2010). A critical examination was provided by Barnett (2003), Barnett and Adger (2007), Raleigh and Urdal (2007) and Nordås and Gleditsch (2007), questioning some of the claims. Dabelko (2009) warns against simplifications and exaggerations. In the following, we discuss the relationship between climate stress, security risks and conflict constellations and highlight some exemplary regional hotspots.

Climate stress, security risks and conflict constellations

From climate stress to societal impacts

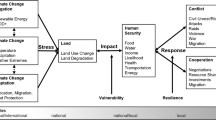

Since human societies rest on certain environmental conditions, a changing climate that significantly alters these conditions is expected to have an impact on human life and society. Understanding the complexity of interactions between climate stress factors, their human and societal impacts and responses is crucial to assess the implications for security and conflict (on the possible causal linkages see Fig. 1, for an expansion of this approach see Scheffran in press).

Rising global temperatures will likely induce environmental changes in many parts of the world. These could include reduced water availability and droughts; soil degradation and reduced food production; increased floods and storms; degradation of ecosystems, loss of biodiversity and spread of diseases; sea-level rise and large-scale climate disruption. There is the possibility of abrupt climate change by triggering “tipping elements” in the climate system (Lenton et al. 2008), such as the weakening of the monsoon, melting of the polar ice sheets or the shutdown of the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation (THC). Each of these climate-induced environmental changes, or a combination thereof, may have impacts on human beings and their societies, depending on their vulnerability and adaptive capacity (for definitions of these terms see IPCC 2007). The consequences are a function of the economic, human and social capital of a society which in turn is influenced by access to resources, information and technology, by social cohesion, and the stability and effectiveness of institutions (Barnett and Adger 2007).

Some of the stress factors may directly threaten human health and life, such as, floods, storms, droughts and heat waves; others gradually undermine well-being over an extended period, such as, food and water scarcity, diseases, weakened economic and ecological systems. Environmental changes caused by global warming not only affect the life of human beings but may also generate larger societal effects, either by undermining the infrastructure of society or by inducing responses and adversely affecting social systems. The associated socio-economic and political stress can erode the functioning of communities, the effectiveness of institutions and the stability of societal structures. Societies which depend more on the environment tend to be more vulnerable to climate stress. The stronger the impact and the larger the affected region the more challenging it becomes for societies to absorb the consequences. For instance, storm and flood disasters could threaten large populations in Southern Asia, the melting of glaciers could jeopardize water supply for people in extended areas in the Andean and Himalayan regions. Large-scale changes in the Earth System, such as the loss of the Amazon rainforest, disruption of the Asian monsoon or the THC shutdown, could have enormous consequences on a continental scale. Combining several of these changes might trigger a cascade of destabilizing events (Karas 2003).

Whether human beings, populations and societies are able to cope with the impacts and restrain the risks depends on their responses to climate change and their abilities to solve associated problems. Some responses may increase the ability to adapt and minimize risks; other responses may lead to additional problems. For instance, migration is a possible response not only to poverty and social deprivation, but also to environmental hardships. An increase in forced migration by climate change would however create more migration hotspots around the world, each becoming a potential nucleus for social unrest (WBGU 2007).

Some regions such as Bangladesh and the African Sahel are more vulnerable due to their geographic and socio-economic conditions and the low level of adaptation capabilities: “Poor communities can be especially vulnerable, in particular those concentrated in high-risk areas. They tend to have more limited adaptive capacities, and are more dependent on climate-sensitive resources such as local water and food supplies.” (IPCC 2007) According to Nordås and Gleditsch (2005) those “with ample resources will be more able to protect themselves against environmental degradation, relative to those living on the edge of subsistence who will be pushed further towards the limit of survival.”

Potential security risks and instabilities

In less wealthy regions, climate change adds to already stressful conditions—high population growth, inadequate freshwater supplies, strained agricultural resources, poor health services, economic decline and weak political institutions—and becomes an additional obstacle to economic growth, development and political stability (UNDP 2007). In societies on the edge of instability, the marginal impact of climate change can make a big difference. “Failing states” with weak governance structures have inadequate management and problem-solving capacities and cannot guarantee the core functions of government, including law, public order and the monopoly on the use of force, all of which are pillars of security and stability.

By triggering a cycle of environmental degradation, economic decline, social unrest and political instability, climate change may become a crucial issue in security and conflict. In several regions of the world (notably in parts of Africa, Asia and Latin America), the decline of social order, state failure and violence could go hand in hand. As the European Commission (2008) notes, climate change “threatens to overburden states and regions which are already fragile and conflict prone.” Security risks could proliferate to neighbouring states, e.g., through refugee flows, ethnic links, environmental resource flows or arms exports. Such spillover effects can destabilize regions and expand the geographical extent of a crisis, overstretching global and regional governance structures (WBGU 2007).

While national and international security have been largely the domain of governments and the military, the concept of “human security” is centred on the security and welfare of human beings (UNDP 1994; King and Murray 2001). It focuses on “shielding people from critical and pervasive threats and empowering them to take charge of their lives” (CHS 2003). Although this term has been disputed by some as being too broad (Paris 2001), it is on the other hand appropriate to assess the diverse threats human beings are facing with climate change.

Several studies and research groups have examined how the scarcity of natural resources—such as minerals, water, energy, fish and land—affects violent conflict and armed struggle: the Toronto Project on Environment, Population and Security (Homer-Dixon 1991, 1994), the Swiss Environment and Conflict Project (ENCOP) (Baechler 1999), the International Peace Research Institute in Oslo (Gleditsch 1997), the Woodrow Wilson’s Environmental Change and Security Project (Dabelko and Dabelko 1995), and Adelphi Research (Carius and Lietzmann 1999). Key issues are still disputed. Buhaug et al. (2008) point to the fact that the number of armed conflicts has clearly declined since the early 1990s, while global mean temperature has risen. There is no clear empirical link between environment and conflict; economic factors are more significant. According to Gleditsch (1998), the meaning of “environmental conflict” is often not clear and important variables are neglected. Barnett (2000) argues that the environment–conflict hypothesis is theoretically rather than empirically driven. Peluso and Watts (2001) provide alternative perspectives on the relationship between violence, resources and environment. Some point out that the abundance rather than the scarcity of natural resources is driving conflict because it strengthens the capacity to fight for some conflict parties (Collier 2000; De Soysa 2000; Le Billon 2001). Under which conditions the struggle for natural resources and livelihood turns into violent conflict is still subject to ongoing research.

A quantitative approach to assess research hypotheses about climate security risks is to extract and represent key indicators in security diagrams for affected regions. These apply fuzzy set theory to convert expert opinion about critical indicators (such as water stress, susceptibility to climate change and societal crisis) into numerical values (Alcamo et al. 2008; Tänzler et al. 2008). Based on this analysis, it is possible to develop adaptive strategies to minimize security risks and mitigate conflicts by strengthening institutions, economic wealth, energy systems and other critical infrastructures.

Conflict constellations

Possible paths to conflict induced by climate change can be categorized into four major conflict constellations, following the scheme introduced in the WBGU (2007) report: water stress, food insecurity, natural disasters and migration.

Water stress

The stress on water resources is represented by the availability of, and access to water, and by the exposure to water-related hazards, such as floods, droughts or illness. More than one billion people are currently without access to clean water (UNDP 2006), and about a quarter of the world’s population lives in water-stressed areas. Increasing population densities, changing patterns of water use and growing economic activities are increasing the pressures on water resources (Arnell 2006). Adding to these pressures, projected climate change will likely alter the magnitude and timing of water stress, directly impact agriculture output (circa 80% of global agriculture is rainfed) and worsen water pollution, with consequences for the environment, human health and economic wealth. Dry areas in sub-Saharan Africa, South Europe, Central China, among others, could experience a shift of climate zones, with increased risks of water shortage, droughts and desertification. Agriculture will compete with urban areas and other business sectors for water supplies.

The relationship between water, security and conflict has been an area of continued debate for over two decades (e.g., Westing 1986; Gleick 1993; Butts 1997; Postel and Wolf 2001; Chatterji et al. 2002). Most literature is based on individual case studies which appear to demonstrate a conflicting water relationship while cooperation has been largely neglected. This literature typically suggests that water scarcity undermines human security and heightens competition for water and land resources, conceiving water scarcity as a form of wealth deprivation that undermines the living conditions of communities. In this view, uneven water distribution may induce migration or the quest for resources in neighbouring regions. A disadvantaged group could seek to displace another group from a more water-rich territory or a water-rich region could secede or otherwise distance itself from central government control.

While this analysis may apply to a number of cases, systematic empirical studies about the link between water and conflict have been lacking until recently. Time series data by Levy et al. (2005) show a significant correlation between rainfall deviations below normal and the likelihood of conflict. A comprehensive study at Oregon State University, based on the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD), supports the hypothesis that the likelihood and intensity of dispute rises as the rate of change within a basin exceeds the capacity to absorb that change (Yoffe et al. 2004). However, historical international relations over shared freshwater resources were overwhelmingly cooperative; violent conflict was rare and far outweighed by the number of international water agreements. The greatest water stress occurs in countries which lack a political and institutional framework for crisis management and conflict resolution. Overall, the assessment demonstrates a complex causal relationship between hydro-climatology and water-related political relations which depends on socio-economic conditions and institutional capacity as well as the timing and occurrence of changes and extremes in a country and basin.

Land use and food security

More than 850 million people are undernourished, and agricultural areas are overexploited in many parts of the world. Climate change will likely reduce crop productivity and worsen malnutrition and food insecurity, with significant variations from region to region. The German Advisory Council anticipates that a global warming of between 2 and 4 degrees Celsius would lead to a drop of agricultural productivity worldwide and that this decrease will be substantially reinforced by desertification, soil salinization, and water scarcity (WBGU 2007). Food production is most severely threatened by global warming in lower latitudes, particularly through loss of cereal harvests and insufficient adaptive capacities (IPCC 2007). A temperature rise of 4°C or more can be expected to have major negative impacts on global agriculture. Climate change in developing countries will likely result in an increase in drylands and areas under water stress. According to FAO (2005), 65 developing countries could lose a cereal production potential of some 280 million tonnes, a loss valued at US$ 56 billion or about 16% of the agricultural gross domestic product of these countries in 1995. In India alone, 125 million tonnes (or 18%) of rainfed cereal production potential could be destroyed.

Africa’s food production is particularly vulnerable to climate change. The per-capita area of agricultural land fell between 1965 and 1990 from 0.5 to 0.3 hectare, and per-capita food production has declined for more than 20 years on the continent. Poor water supply or water scarcity (for drinking water and irrigation) could significantly reduce yields from rain-fed agriculture in some African countries, severely compromising access to food in the coming decades, according to the IPCC (2007). This may well trigger regional food crises, a global increase in food prices and further undermine the economic performance of weak and unstable states. The predicted loss of agricultural land in the region due to climate change could lead to a significant additional decline in food production with potentially serious implications. For instance, soil degradation, population growth and unequal land distribution transformed the environmental crisis in Rwanda into a nationwide crisis, giving radical forces an opportunity to escalate ethnic rivalries into a genocide (Percival and Homer-Dixon 1995).

Natural disasters

The IPCC projects extreme weather events and associated natural disasters, including droughts, heat waves, wildfires, flash floods, and tropical and mid-latitude storms, to occur more frequently and more intensely in many areas of the globe as a consequence of climate change. Sea-level rise, intensive storms and heavy precipitation would increase the risk of natural disasters in coastal zones, in particular in South Asia, China and the USA. These events generate rising economic and social costs, not to mention human casualties, and may have contributed to conflict in the past, especially during periods of domestic political tension. Some regions especially at risk from storms and floods, such as Central America, Southern Asia and Southern Africa, generally have weak economies and governments, making adaptation and crisis management more difficult. Damage from frequent storms and flooding along the densely populated eastern coasts of India and China could intensify already difficult-to-control migration processes. Disastrous events often exceed the ability of the affected societies to cope with the magnitude and speed of these events and are usually associated with a temporary local collapse of state functions which may lead to domestic political tension and conflict. Disaster management is important to control and prevent the further escalation of a crisis into conflict.

Environmental migration

Where living conditions become unbearable, people are forced to leave their homeland. The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that in 2006 there were 8.4 million registered refugees worldwide and 23.7 million internally displaced persons. According to environmental scientist Norman Myers, the total number of environmental migrants could rise to 150 million by 2050, up from 25 million in the mid-1990s (Myers 2002), a number that has been used in the 2006 Stern Review in the context of climate change. Although these estimates are disputed due to lack of empirical evidence, the number of environmental migrants is expected to rise in response to environmental degradation and weather extremes, or the indirect consequences such as economic decline and conflict. In many cases, displaced people will appear as economic migrants (e.g., farmers loosing income) or as refugees of war (from environment-induced conflict).

Most vulnerable are coastal and riverine zones, hot and dry areas and regions whose economies depend on climate-sensitive resources. Environmental migration will predominantly occur within national borders of developing countries, but industrialized regions would also be affected by an external migratory pressure. Europe could see an increase in migration from sub-Saharan Africa and the Arab world, and North America from the Caribbean, and Central and South America. China’s potential need to resettle large populations from flooded coastal regions or dry areas may pressure Russia, a country with a declining population and a huge energy- and mineral-rich territory that may become more agriculturally productive in a warming climate (Campbell et al. 2007).

Migration of people can increase the likelihood of conflict in transit and target regions. Environmental migrants compete with the resident population for scarce resources, such as, farmland, housing, water, employment, and basic social services; in certain cases they are perceived to upset the “ethnic balance” in a region (Reuveny 2007). A sudden mass exodus after an extreme weather event is different from a planned migration in response to a gradual environmental degradation. How well local and national governments function influences the likelihood of conflict. In countries without weather warning systems or evacuation plans, extreme weather causes relatively greater damage and forces more people to migrate than in countries whose governments are well prepared for emergencies (WBGU 2007). Affected governments face enormous challenges if they have to handle sudden, unexpected and large-scale migration which can even overwhelm the management capacities of developed countries (e.g., Spain’s problems with West African boat people, or displaced people after Hurricane Katrina).

Regional climate security risks

Whether climate change favours conflict or cooperation critically depends on the perceptions and responses of the actors involved and on societal structures and institutions. The connections are complex and a function of political and economic circumstances. Since global warming affects each region of the world differently, regional case studies are important to explore the relationship between climate, security and conflict in detail (for a comprehensive list of environmental conflicts see Carius et al. 2006). Some of the potential climate-related environmental impacts and societal implication have been integrated into a world map to show potential regional hotspots (Fig. 2). The given cases, which are not meant to be complete, indicate that climate change could have adverse effects on human security and social stability in many parts of the world, although predictions are difficult due to future uncertainties and complexities. The dark spots in the map show some ongoing conflicts which are potentially influenced by, or related to, environmental and climate factors. Regional climate impacts are described in other chapters of this volume in more detail (see also Hare 2006; Schellnhuber et al. 2006); possible links to security and conflict are described in the following for a few cases.

Land-use conflict in Northern Africa

A series of drought events affected the Northern African regions since the 1970s. UNEP (2007) estimates that the boundary between semi-desert and desert in Sudan has moved southward by an estimated 50–200 km since the 1930s and would continue to move in case of declining precipitation (which is disputed in the literature). The loss in agricultural land would lead to a significant drop in food production. Desertification has pushed population from the north to move southward, contributing to the historic struggle for land between herders and farmers (Schilling et al. 2010). For decades, Arab nomads and African villagers alternately skirmished and supported each other as they raised livestock and tended fields under resource constraints. The delicate balance has been upset by drought, desertification, crop failure and widespread food insecurity, which forced increased migration of nomadic groups from neighbouring states into the more fertile areas. Arabic herders from the north migrated south in the dry season in search of water sources, and their cattle grazed on the fields of African farmers. While this immigration was initially absorbed by the indigenous groups, the increased influx combined with tougher living conditions during the drought led to clashes and tensions between the newcomers and the locals.

As a notable example of how climate change may influence land-use conflicts in the region, the conflict in Darfur Sudan has been mentioned. This particularly violent conflict has a long history and various roots, with the environment likely playing only a secondary role. Traditionally, differences between farmers and herders were resolved in the region by negotiation among tribal leaders, but the government’s attempt to establish new administrative structures weakened the established tribal system (International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur 2005). Inter-tribal conflict was further aggravated by access to weapons, partly fuelled by oil revenues. The decision of the government to arm the Janjaweed militia against the rebels has escalated to a full-scale civil war which remained unsolved, despite the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (ICG 2004).

A study by Sandia Research Labs assesses the role of climate factors in this conflict (Boslough et al. 2004). An empirical analysis, based on O’Brien (2002), shows statistical correlations between conflict instability and different indicators, such as income and calories per capita, life expectancy, youth bulge, infant mortality rate, and trade openness, ethnic composition of the population, political freedom and democratic rights. While some of these factors tend to worsen the conflict constellation, a clear overall message was not provided. The Sudan Post-Conflict Environmental Assessment of the UN Environmental Programme (UNEP 2007), based on an extensive expert assessment, comes to the conclusion that critical environmental issues, including land degradation, deforestation and the impacts of climate change, threaten the Sudanese people’s prospects for long-term peace, food security and sustainable development. Darfur is considered a “tragic example of the social breakdown that can result from ecological collapse” (UNEP 2007). After publication of the report, regional experts did not refute the environmental contribution to the conflict but warned of the “danger of oversimplifying Darfur” (Butler 2007).

Recent empirical results are contradictory regarding the link between climate change and conflict in Africa. Burke et al. (2009) suggest that for the period 1981–2002, the number of conflicts is positively correlated with temperature and predict a strong increase in the number of conflicts and casualties by 2030. These results are questioned by Buhaug (2010) who shows that modifications in the statistical approach lead to completely different results.

Floods, storms and sea-level rise in Southern Asia

According to Working Group 2 of IPCC (2007), coastal areas, especially heavily populated mega-deltas in South, East and Southeast Asia, will be at greatest risk due to increased flooding from the sea and, in some mega-deltas, flooding from the rivers. Where cities, or parts of cities, lie below or slightly above sea level—such as on many coasts of Southern or Southeast Asia—the danger of floods and storms is particularly severe. Many coastal cities are located on the estuaries of large rivers. Worldwide, more than 150 regions are at risk from flooding, and in China alone 45 cities and districts are estimated to be affected (WBGU 2007).

The Bay of Bengal region, which covers part of Orissa, west Bengal in India and Bangladesh, is most vulnerable to extreme weather events and climate change, threatening human security for a large population. The coastal area is frequently hit by tropical cyclones causing extensive loss of life and property. Reasons for these extreme impacts are the shallow coastal waters in the Bay, the high tidal range, a large number of inlets in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna deltaic system, unfavourable cyclone tracks and the high population density (Dube et al. 2004). Each year, millions of people are affected by extreme weather events, and since 1960, about 600,000 persons have died due to cyclones, storm surges and floods (IFRC 2002).

Climate change would significantly aggravate human insecurity in Bangladesh, one of the poorest and most densely populated countries of the world. During the monsoon season often about one-quarter of Bangladesh is flooded by rain and river water and up to 60% of the land is submerged in years with high floods. The impacts of projected sea-level rise could be disastrous, threaten the whole economy and exacerbate insecurity. Most affected would be the region’s ecosystems and biodiversity, water, agricultural, forestry, fisheries and livestock resources. A one-metre increase in the sea-level could inundate about 17% of Bangladesh and displace some 40 million people (World Bank 2000, p. 100). The intrusion of seawater (salinization) would destroy large amounts of agricultural land and decrease agricultural productivity. More people would be forced to leave threatened areas (if they are able to move) and settlements will spread to higher and flood-protected lands. The health conditions of poor and malnourished people are expected to worsen (Ericksen et al. 1996).

On several occasions, the migration of impoverished people has already contributed to violent clashes within Bangladesh and between emigrating Bangladeshi and tribal people in Northern India (especially in Assam) where several thousand people died (Brauch 2002; WBGU 2007). The complex interaction of both human- and nature-induced trends and their socio-economic and political implications may further lead to situations of political instability and violent clashes (some case studies have been analysed by Hafiz and Islam 1996). With climate change, human insecurity and the fight for survival are likely to increase in Bangladesh, challenging internal social and political stability and undermining the young democratic institutions.

Glacier melting and water insecurity in Central Asia and Latin America

More than three quarters of the farmland in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan is irrigated, using up to 90% of the region’s water resources. Hydroelectric power supplies most of the region with its electricity. Both activities depend on glacial melt water from nearby mountain ranges. The IPCC projects a sharp temperature rise in Central Asia and a significant glacier loss in the next decades. This trend puts at risk the hydroelectric power infrastructure and agriculture and threatens the population with severe flood events. Central Asian states are suffering from a number of economic and political problems, including largely closed economic markets, extreme social disparities, weak state structures and corruption, affecting their ability to cope with such massive changes (WBGU 2007). In the past, struggles over land and water resources played a major role in this region, which are further aggravated by ethnic disputes, separatist movements, and the presence of religious-fundamentalist groups.

Another potential hotspot for climate-induced water conflicts is Peru’s capital city of Lima, with a population projected to grow by nearly 5 million by 2030. Coupled with increasing water demand the loss of nearby glaciers will exacerbate pressure on the city’s water supplies in the coming decades (WBGU 2007). Scientists project that global warming will melt the lower altitude glaciers within a few decades. Extreme water scarcity may aggravate societal problems, such as, social inequality, under-employment, and poverty, increasing crime rates and police corruption. Peru’s energy supply also stands to be affected because about four-fifths of the country’s electricity comes from hydroelectric power stations, which rely on fluctuating and unreliable water resources.

Water conflicts in the Middle East

Water has traditionally been a strategic issue in the Middle East, intertwined with the region’s deeply rooted conflicts (for a survey, see Biswas 1994; Wolf 1995; Amery and Wolf 2000; Shuval and Dweik 2007). The arid climate, the imbalance between water demand and supply, and the ongoing confrontation between key political actors exacerbate the water crisis. Since much of the water resources are trans-boundary, water disputes often coincide with land disputes. Competition over the utilization of shared resources has been observed for the rivers Nile, Euphrates and Jordan. Most contentious has been the sharing of the water of the Jordan River basin among Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and the Palestinians, raising issues of equity (Phillips et al. 2006). Israel receives more than half of its water resources from occupied Arab territories and has a higher per-capita consumption than its neighbours. Reduced water supply over an extended period also bears a conflict potential among the countries in the Nile basin. In particular, Egypt depends on the Nile for 95% of its drinking and industrial water and could feel threatened by countries upstream that exploit the water from the river. While this increases the chances for political crisis and violent clashes, it could also increase the need for agreements to regulate water distribution (Link et al. 2010).

Exaggerated statements on “water wars” have been questioned (Libiszewski 1995). The region’s conflicts are largely determined by political differences, where water-related problems represent an additional dimension that may contribute to conflict as well as cooperation. Among cooperative endeavours have been the Johnston Negotiations of 1953-1955 and the talks between Israel and Jordan, and negotiations over the Yarmouk River and the Unity Dam in the 1970s and 1980s. Further progress is connected to the fate of the Middle East Peace Process. Hydrological issues have been treated in all major agreements, and the bilateral Peace Treaty of October 1994 explicitly lists a series of common water projects. Critical issues need to be resolved in future negotiations, taking into account the uncertainties of natural variation and climate change. Besides technical and economic solutions that increase supply or decrease demand of water, resolving the water crisis can be done most effectively by offering joint management, monitoring and enforcement strategies and by encouraging greater transparency in water data across boundaries (Medzini and Wolf 2004). The conditions for cooperative solutions may decline due to population growth, over-exploitation and pollution. Global warming is projected to increase the likelihood and intensity of droughts in the region (IPCC 2007), undermining the conditions for peace and human security.

Climate security in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean region (Southern Europe and North Africa, without the Middle East which is discussed in the previous section) will be severely affected by global warming. Rising temperatures are expected to exacerbate existing pressures on limited water resources because of reduced rainfall and loss of snow/glacial melt water, adding to existing problems of desertification, water scarcity and food production (IPCC 2007; Stern et al. 2006). As already discussed, water scarcity has a negative impact on agricultural and forestry yields and on hydropower. Heat waves and forest fires compromise vegetation cover and add to existing environmental problems. Ecosystem change affects soil quality and moisture, carbon cycle and local climate. Population pressures and water-intensive activities, such as irrigation, already strain the water supplies, posing dangers to human health, ecosystems and national economies of countries. Within the region, there are significant differences with regard to vulnerability and problem-solving capacity.

Southern Europe is characterized by relatively high economic and social capability, which can be further backed up by support from the EU to mitigate the impact and make long-term adaptation possible (Brauch 2010). Despite expected environmental changes, outbreaks of violence and conflict are less likely.

By contrast, the environmental situation in North Africa is significantly worse than in Southern Europe. Climate change interacts with the region’s notorious problems, including high population growth, dependence on agriculture and weak governance. Countries are far more vulnerable, less able to adapt and more prone to conflict.

In Southern Europe, a temperature rise of 2 degrees Celsius might decrease summer water availability by 20–30%; a rise of 4 degrees Celsius would decrease availability by 40–50% (Stern et al. 2006, part 2, p. 123). Climate change could lead to a general northward shift in summer tourism, agriculture, and ecosystems. The Canary Islands, the south of Italy and Spain, part of Greece and Turkey experience an increasing competition for resources among different sectors, especially water and land. Climate change may endanger the tourism sector, the main employer in the region through increasing temperatures, forest fires and water stresses. Governments may find it increasingly difficult to sustain current living standards and provide development opportunities.

Lack of usable land and water resources adds to impoverishment and forces people to move from rural areas to cities. River deltas are at risk from sea-level rise and salinization. For a 50 cm sea-level rise salt water would penetrate 9 km into Nile aquifers, affecting agriculture and the whole economy (WBGU 2007). Desertification can affect the stability of the Mediterranean region and trigger large-scale migration and conflict. European countries along the Mediterranean already face pressures from African immigrants. It is unlikely, however, that climate change alone would lead to conflict, rather it could interact with other forces, such as unemployment, economic recession and unstable political regimes.

Impacts on rich countries

While the impacts on some developed countries may be moderate or even positive at small temperature change (greater agricultural productivity, reduced winter heating bills, fewer winter deaths), they are expected to become more damaging at higher temperatures. The Stern Review (Stern et al. 2006, part 2, p. 138) concludes that the costs of climate change for developed countries “could reach several percent of GDP as higher temperatures lead to a sharp increase in extreme weather events and large-scale changes”.

A striking example has been Hurricane Katrina, the most costly natural disaster so far, which severely affected a whole region of the United States and demonstrated the vulnerability of the world’s most powerful nation and its inability to cope with such a natural disaster. When Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast with wind speeds of up to 230 km per hour, it left a trail of destruction over an area as large as Britain. Temporary shelters in the Superdome and the Convention Center were overrun with lawlessness. In fact, the storm devastated the city’s entire civil infrastructure, including its water and sanitation systems, energy supplies, and communications and transportation networks. The failure of local and national authorities to manage the disaster plunged the state and federal governments into a crisis of public confidence. As was demonstrated in New Orleans, the poorest people in developed countries will be the most vulnerable to future disasters. Poor people are more likely to live in higher-risk areas, and have fewer financial resources to cope with climate change, including lack of comprehensive insurance cover (Stern et al. 2006).

Rising temperatures exacerbate existing water shortages on dry land in Southern Europe, California and South West Australia. They reduce human security and agricultural output, increase the investment required in infrastructure and the costs of damaging storms and floods, droughts, heat waves and forest fires. During the 2003 heat wave in Europe, more than 35,000 people died and agricultural losses reached $15 billion. Abrupt and large-scale changes in the climate system could have a direct impact on the economies of developed countries. As the impacts become increasingly damaging, they may have severe consequences for global trade and financial markets (Stern et al. 2006) and eventually affect civil order and stability.

From climate conflict to climate cooperation

Despite uncertainties, the potential impacts of climate change provide strong arguments for the developed world to take the lead in achieving the ultimate goal of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) which in Article 2 demands stabilization of atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations at levels that “prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system”. With the formula of “common but different responsibilities” the UNFCCC assigned different roles for industrialized and developing countries in climate policy. As the largest emitters of greenhouse gases they have a particular responsibility as well as the power to reach an agreement on actually reducing emissions to a level that keeps the risks within limits. The wealthy countries have relevant adaptation capabilities and better means to maintain order and stability.

Since the Kyoto Protocol was signed in 1997, a conflict on the distribution of different obligations has been emerging. In this context, the interpretation and implementation of Art. 2 UNFCCC is critical (Ott et al. 2004). To overcome diverging interests, it is important to build coalitions among those with mutual interests (Scheffran 2008). To specify the conditions for a cooperative solution, the trade-offs between growth and emission targets among industrialized and developing countries can be utilized (Ipsen et al. 2001). Cooperation becomes feasible if voluntary participation is in the developing countries’ own interests, e.g., because it supports local development and environmental goals or access to advanced technology and investment. As has been demonstrated in the reports by the IPCC, the Stern Review and others a wide range of options is available to move from conflict to cooperation. To address the security risks, a comprehensive set of measures has been suggested by WBGU (2007) as part of a preventive security policy that avoids climate change becoming a threat multiplier. Instead, the UN report on climate security identifies several “threat minimizers” such as “climate mitigation and adaptation, economic development, democratic governance and strong local and national institutions, international cooperation, preventive diplomacy and mediation…” (UNGA 2009, p. 2).

A promising opportunity for strengthened North–South cooperation is the vision of linking Europe to North Africa with electric power lines. This vision is not new. It has been developed by DESERTEC (2007, 2008), by Czisch (1999), Czisch and Giebel (2007) and was further extended and complemented with new approaches in the SuperSmartGrid concept (Battaglini et al. 2009). Recently it has reached the top of the political agenda and attracted interest from a broad spectrum of actors. Europe sees the possibility of producing a large quantity of electricity from renewable sources in North Africa to combat climate change, meet its emission reduction and renewable energy obligations, decrease energy dependency and, at the same time, engage with a neighbouring developing country region. Generally speaking, North African countries, each of them with national peculiarities, see the opportunity of meeting the increasing local energy demand, to attract substantial foreign investments, generate export benefits and open the way to technology sharing, employment opportunities and economic desalination.

A strong cooperation between Europe and the North African countries on energy security and climate security could benefit the entire region, increase adaptive capacity, substantially contribute to emission reduction especially in the power sectors and create the preconditions for long-term stability. Climate change impacts in the region are expected to create a broad spectrum of risks cascading down to affect several economic sectors and aspects of society, as discussed in the previous section. Cooperation centred on the expansion of renewable energy for local and export purposes in North Africa would create a different pattern of economic growth, opportunities and interdependencies. Increased and sustainable desalination options could lower competition among sectors for water resources; foreign investments could have a positive impact on the high employment rate in North Africa, thus lowering the pressure to migrate north. Moreover, experience gained in the region could be beneficial in other developing countries and provide positive examples for the post 2012 negotiations on how to engage non-Annex I country regions.

Conclusions

The causal chain from climate stress to human and societal impacts is complex and not fully understood. While the research literature does not provide a clear evidence of the environment-conflict hypothesis from previous cases, the magnitude of climate change has the potential to undermine human security and overwhelm adaptive capacities of societies in many world regions. The most serious climate risks and conflicts are expected in poor countries which are vulnerable to climate change and have less access to capital to invest in adaptation, but more wealthy countries are not immune. As climate change raises existing inequalities between rich and poor, pressures for large-scale migration could emerge on a regional and global scale. Devastating effects in developing countries on food and water availability, and large-scale events such as monsoon failure or loss of glacial melt water, could trigger population movements and regional conflicts. Developed countries cannot ignore the economic impacts and the migratory pressures and may be drawn into climate-induced conflicts in regions that are hardest hit by the impacts. A preventive climate policy would seek to strengthen institutions and cooperation between developing and developed countries to build a global security community against climate change.

References

Alcamo J, Acosta-Michlik L, Carius A, Eierdanz F, Klein R, Krömker D, Tänzler D (2008) Quantifying vulnerability to drought from different interdisciplinary perspectives. Reg Environ Change 8(4):137–149

Amery HA, Wolf AT (2000) Water in the Middle East: a geography of peace. University of Texas Press, Austin

Arnell NW (2006) Climate change and water resources. In: Schellnhuber HJ, Cramer W, Nakicenovic N, Wigley T, Yohe G (eds) Avoiding dangerous climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 167–170

Baechler G (1999) Environmental degradation in the south as a cause of armed conflict. In: Carius A, Lietzmann K (eds) Environmental change and security: a European perspective. Springer, Berlin, pp 107–130

Barnett J (2000) Destabilizing the environment-conflict thesis. Rev Int Stud 26(02):271–288

Barnett J (2003) Security and climate change. Global Environ Change 13(1):7–17

Barnett J, Adger WN (2007) Climate change, human security and violent conflict. Polit Geogr 26:639–655

Battaglini A, Lilliestam J, Haas A, Patt A (2009) Development of supersmart grids for a more efficient utilisation of electricity from renewable sources. J Cleaner Product 17(10):911–918

BBC (2007) UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon has warned that climate change poses as much of a danger to the world as war. http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/in_depth/6410305.stm

Biswas AK (1994) International waters of the Middle East: from Euphrates-Tigris to Nile. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Boslough M, Sprigg J, Backus G, Taylor M, McNamara L, Fujii J, Murphy K, Malczynski L, Reinert R (2004) Climate change effects on international stability: a white paper. Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque

Brauch HG (2002) Climate change, environmental stress and conflict. In: German Federal Ministry for the Environment (ed) Climate change and conflict. German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Berlin, pp 9–112

Brauch HG (2009) Securitizing global environmental change. In: Brauch HG, Oswald Spring Ú, Grin J et al (eds) Facing global environmental change. Springer, Berlin, pp 65–102

Brauch HG (2010) Climate change and mediterranean security. Papers IEMed. European Institute of the Mediterranean, Barcelona

Brown N (1989) Climate, ecology and international security. Survival 31(6):519–532

Brown O (2007) Weather of mass destruction? The rise of climate change as the ‘new’ security issue. International Institute for Sustainable Development, London, UK, http://www.iisd.org/pdf/2007/com_weather_mass_destruction.pdf

Brzoska M (2009) The securitization of climate change and the power of conceptions of security. Secur Peace 27(3):137–145

Buhaug H (2010) Climate not to blame for African civil wars. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 107(38):16477–16482

Buhaug H, Gleditsch NP, Theisen OM (2008) Implications of climate change for armed conflict. In: Mearns R, Norton A (eds) The social dimensions of climate change: equity and vulnerability in a warming world. The World Bank, Washington, DC, pp 75–101

Burke MB, Miguel E, Satyanath S, Dykema JA, Lobell DB (2009) Warming increases the risk of civil war in Africa. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 106(49):20670–20674

Butler D (2007) Darfur’s climate roots challenged. Nature 447(7148):1038

Butts K (1997) The strategic importance of water. Parameters 27(1):65–83

Campbell KM, Weitz R, Gulledge J, McNeill JR, Podesta J, Ogden P, Fuerth L, Woolsey RJ, Lennon AT, Smith J (2007) The age of consequences: the foreign policy and national security implications of global climate change. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Center for a New American Security, Washington, DC

Carius A, Lietzmann K (eds) (1999) Environmental change and security: a European perspective. Springer, Berlin

Carius A, Tänzler D, Winterstein J (2006) Weltkarte von Umweltkonflikten–Ansätze zur Typologisierung. Externe Expertise für das WBGU Hauptgutachten “Welt im Wandel: Sicherheitsrisiko Klimawandel. WBGU, Berlin

Carius A, Tänzler D, Maas A (2008) Climate change and security—challenges for German development cooperation. Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit, Eschborn

Chatterji M, Arlosoroff S, Guha G (2002) Conflict management of water resources. Ashgate Publishing, Aldershot

CHS (2003) Human security now. Commission on human security, New York

CNA Corporation (2007) National security and the threat of climate change. The CNA Corporation, Alexandria

Collier P (2000) Economic causes of civil conflict and their implications for policy. World Bank, Washington DC

Czisch G (1999) Potentiale der regenerativen Stromerzeugung in Nordafrika. Universität Kassel, Kassel

Czisch G, Giebel G (2007) Realisable scenarios for a future electricity supply based 100% on renewable energies. In: Proceedings of the Bisø international energy conference 2007—energy solutions for sustainable development, pp 186–195

Dabelko GD (2009) Avoid hyperbole, oversimplification when climate and security meet. Bull Atomic Sci. http://www.thebulletin.org/node/7730

Dabelko GD, Dabelko DD (1995) Environmental security: issues of conflict and redefinition. environmental change and security project report 1. Woodrow Wilson Center, Washington, DC

De Soysa I (2000) The resource curse: are civil wars driven by rapacity or paucity? In: Berdal M, Malone D (eds) Greed and grievance: economic agendas and civil wars. Lynne Rienner, Boulder, pp 113–136

Desertec (2007) Clean power from deserts—the DESERTEC concept for energy, water and climate security. White paper, 3rd edn. The Club of Rome, Hamburg

Desertec (2008) Our vision of the union for the Mediterranean: the DESERTEC concept. Deserts and technology for energy, water and climate security. The Club of Rome, Hamburg

UNDP (2006) Beyond scarcity: power, poverty and the global water crisis. Human Development Report 2006. United Nations Development Program, New York

Dube SK, Chittibabu P, Sinha PC, Rao AD, Murty TS (2004) Numerical modelling of storm surge in the head bay of Bengal using location specific model. Nat Hazards 31(2):437

Edwards MJ (1999) Security implications of a worst-case scenario of climate change in the South-west Pacific. Aust Geogr 30:311–330

Ericksen NJ, Ahmad QK, Chowdhury AR (1996) Socio-economic implications of climate change for Bangladesh. In: Warrick RA, Ahmad QK (eds) The implications of climate and sea-level change for Bangladesh. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 205–288

European Commission (2008) Climate change and international security. Paper from the high representative and the European Commission to the European Council. S113/08, 2nd edn. Brussels

FAO (2005) Impact of climate change, pests and diseases on food security and poverty reduction—background document. 31st Session of the Committee on World Food Security. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, Rome

Gilman N, Randall D, Schwartz P, Blakely T, Tobias M, Atkinson J, Yeh LC, Huang K (2007) Impacts of climate change: a system vulnerability approach to consider the potential impacts to 2050 of a mid-upper greenhouse gas emissions scenario. Global Business Network, San Francisco

Gleditsch NP (1998) Armed conflict and the environment: a critique of the literature. J Peace Res 35(3):381–400

Gleditsch NP (ed) (1997) Conflict and the environment. NATO ASI series, vol 33. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

Gleick PH (1989) The implications of global climatic changes for international security. Climatic Change 15(1/2):309–325

Gleick P (1993) Effects of climate change on shared fresh water resources. In: Mintzer I (ed) Confronting climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 127–140

Hafiz MA, Islam N (1996) Environmental degradation and intra/interstate conflicts in Bangladesh. In: Baechler G, Spillmann KR (eds) Environmental degradation as a cause of war: regional and country studies of research fellows. Rüegger, Chur-Zürich

Hare B (2006) Relationship between increases in global mean temperature and impacts on ecosystems, food production, water and socio-economic systems. In: Schellnhuber H-J, Cramer W, Nakicenovic N, Wigley T, Yohe G (eds) Avoiding dangerous climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 177–186

Homer-Dixon T (1991) On the threshold: environmental changes as causes of acute conflict. Int Security 16(2):76–116

Homer-Dixon T (1994) Environmental scarcities and violent conflict: evidence from cases. Int Security 19(1):5–40

ICG (2004) Now or never in Africa. Africa Report N°80. International Crisis Group, Nairobi

IFRC (2002) World disasters report 2002 focus on reducing risk. International Federation of the Red Cross

International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur (2005) Report of the International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur to the United Nations Secretary-General, Geneva

IPCC, 2007: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ipsen D, Rösch R, Scheffran J (2001) Cooperation in global climate policy: potentialities and limitations. Energy Policy 29(4):315–326

Karas TH (2003) Global climate change and international security. Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque

King G, Murray CJL (2001) Rethinking human security. Polit Sci Q 116(4):585–610

Le Billon P (2001) The political ecology of war: natural resources and armed conflicts. Polit Geogr 20(5):561–584

Lenton T, Held H, Kriegler E, Hall J, Lucht W, Rahmstorf S, Schellnhuber HJ (2008) Tipping elements in the Earth`s climate system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:1786–1793

Levy MA, Thorkelson C, Vörösmarty C, Douglas E, Humphreys M (2005) Freshwater Availability anomalies and outbreak of internal war: results from a global spatial time series analysis. Paper presented at the international workshop “human security and climate change”, Oslo, Norway, 21–23 June

Libiszewski S (1995) Water disputes in the Jordan basin region and their role in the resolution of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. ENCOP Occasional Paper No. 13 August 1995. Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research at the ETH Zurich and Swiss Peace Foundation Berne, Zurich

Link M, Piontek F, Scheffran J, Schilling J (2010) Integrated assessment of climate security hot spots in the Mediterranean region—potential water conflicts in the Nile river basin. Paper presented at the conference “climate change and security”, Trondheim, Norway, 21–24 June 2010. http://climsec.prio.no/papers/ManuscriptLink-etalTrondheim2010.pdf

Medzini A, Wolf AT (2004) Towards a Middle East at peace: hidden issues in Arab-Israeli hydropolitics. Int J Water Resour Dev 20(2):193–204

Myers N (2002) Environmental refugees: a growing phenomenon of the 21st century. Philos Trans Royal Soc London Series B 357:609–613

Nobel (2007) The Nobel Peace Prize for 2007

Nordås R, Gleditsch NP (2005) Climate conflict: common sense or nonsense? Paper presented at the international workshop "Human security and environmental change", Oslo, Norway, 21–23 June

Nordås R, Gleditsch NP (2007) Climate change and conflict. Polit Geogr 26:627–638

O’Brien SP (2002) Anticipating the good, the bad, and the ugly: an early warning approach to conflict and instability analysis. J Conflict Resol 46(6):791–811

Ott K, Klepper G, Lingner S, Schäfer A, Scheffran J, Sprinz D, Schröder M (2004) Reasoning goals of climate protection. Specification of Article 2 UNFCCC. Report for the Federal Environmental Agency, Berlin. Europäische Akademie GmbH, Berlin

Paris R (2001) Human security: paradigm shift or hot air? Int Security 26(2):87–102

Peluso NL, Watts MJ (eds) (2001) Violent environments. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Percival V, Homer-Dixon T (1995) Environmental scarcities and violent conflict: the case of Rwanda. American Association for the advancement of science, Project on Environment. Population and Security, Washington DC

Phillips D, Daoudy M, McCaffrey S, Öjendal J, Turton A (2006) Trans-boundary water cooperation as a tool for conflict prevention and for broader benefit-sharing. Phillips Robinson and Associates, Windhoek

Postel SL, Wolf AT (2001) Dehydrating conflict. Foreign Policy 126:60–67

Rahman A (1999) Climate change and violent conflicts. In: Suliman M (ed) Ecology, Politics and Violent Conflict. Zed Books, London, pp 181–210

Raleigh C, Urdal H (2007) Climate change, environmental degradation and armed conflict. Polit Geogr 26:674–694

Reuveny R (2007) Climate change-induced migration and violent conflict. Polit Geogr 26:656–673

Scheffran J (1997) Conflict potential of energy-related environmental changes—the case of global warming (in German). In: Bender W (ed) Verantwortbare Energieversorgung für die Zukunft. Darmstadt, pp 179–218

Scheffran J (2008) Preventing dangerous climate change. In: Grover VI (ed) Global warming and climate change, vol 1. Science Publishers, Enfield, pp 493–526

Scheffran J (2009) The gathering storm—is climate change a security threat? Security Index 87(2):21–31

Scheffran J (in press) The security risks of climate change: vulnerabilities, threats, conflicts and strategies. In: Brauch HG, Oswald Spring Ú, Kameri-Mbote P et al (eds) Coping with global environmental change, disasters and security. Springer, Berlin, pp 735–756

Scheffran J, Jathe M (1996) Modelling the impact of the greenhouse effect on international stability. In: Kopacek P (ed) Supplementary ways for improving international stability. IFAC, Pergamon, pp 31–38

Schellnhuber H-J, Cramer W, Nakicenovic N, Wigley T, Yohe G (eds) (2006) Avoiding dangerous climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Schilling J, Scheffran J, Link PM (2010) Climate change and land use conflicts in Northern Africa. Nova Acta Leopoldina NF 112(384):173–182

Shuval H, Dweik H (eds) (2007) Water resources in the Middle East: Israel-Palestinian water issues–from conflict to cooperation. Springer, Berlin

Smith D, Vivekananda J (2007) A climate of conflict. The links between climate change, peace and war. International Alert, http://www.international-alert.org/pdf/A_Climate_Of_Conflict.pdf

Stern N, Peters S, Bakhshi V, Bowen A, Cameron C, Catovsky S, Crane D, Cruickshank S, Dietz S, Edmonson N, Garbett S-L, Hamid L, Hoffman G, Ingram D, Jones B, Patmore N, Radcliffe H, Sathiyarajah R, Stock M, Taylor C, Vernon T, Wanjie H, Zenghelis D (2006) The economics of climate change: the Stern Review. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Swart R (1996) Security risks of global environmental changes. Global Environ Change Part A 6(3):187–192

Tänzler D, Carius A, Maas A (2008) Assessing the susceptibility of societies to droughts: a political science perspective. Reg Environ Change 8(4):161–172

UNDP (1994) New dimensions of human security. Human development report 1994. United Nations Development Program, New York

UNDP (2007) Fighting climate change. Human Development Report 2007. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

UNEP (2007) Sudan: post-conflict environmental assessment. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi

UNGA (2009) Climate change and its possible security implications. UN Secretary-General’s Report A/64/3. New York, USA

UNSC (2007) Security Council holds first-ever debate on impact of climate change on peace, security, hearing over 50 speakers. UN Security Council, 5663rd Meeting 17 April 2007. http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2007/sc9000.doc.htm

Van Ireland E, Klaassen M, Nierop T, Van der Wusten H (1996) Climate change: socio-economic impacts and violent conflict. Dutch national programme on global air pollution and climate change. Report no 410200006. Environmental Economics and Natural Resources Group, Wageningen

WBGU (2007) World in transition–climate change as a security risk. German Advisory Council on Global Change, Earthscan

Webersik C (2010) Climate change and security—a gathering storm of global challenges. Praeger, Connecticut

Westing AH (1986) Global resources and international conflict: environmental factors in strategic policy and action. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Wolf A (1995) Hydropolitics along the Jordan River: the impact of scarce water resources on the Arab–Israeli conflict. United Nations University Press, New York

World Bank (2000) World Development Report 1999/2000. Oxford University Press, New York

Yoffe S, Fiske G, Giordano M, Giordano MA, Larson K, Stahl K, Wolf AT (2004) Geography of international water conflict and cooperation: Data sets and applications. Water Resour Res 40(5)

Acknowledgments

Research for this publication was supported in parts through the Cluster of Excellence ‘CliSAP’ (EXC177), University of Hamburg, funded through the German Science Foundation (DFG). The work on this article was done between summer 2006 and summer 2010 and reflects some of the significant changes in the debate on the securitization of climate change that occurred in between.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scheffran, J., Battaglini, A. Climate and conflicts: the security risks of global warming. Reg Environ Change 11 (Suppl 1), 27–39 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-010-0175-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-010-0175-8