Abstract

OMERACT proposed a set of mandatory and discretionary domains to evaluate the effect of treatment in patients with gout. To determine the percentage of improvement and the effect size 6 and 12 months after starting a proper treatment in patients with gout from our cohort (GRESGO) based on the OMERACT proposal for chronic gout. GRESGO is a cohort of consecutive, new patients with gout attending either of two dedicated clinics. This report includes 141 patients evaluated at baseline and 6 months plus 101 of them completing a 12-month follow-up in 2012. Clinical data including the OMERACT domains for chronic gout were collected at baseline and every 6 months. Treatment was prescribed by their attending physician with the purpose of getting < 6 mg/dL of seric uric acid (sUA). Most patients were males (96%) with inappropriate treatment (95%); 66% had tophi, 30% metabolic syndrome, and 32% low renal function. Mean dose of allopurinol at baseline and throughout the study went from 344 ± 168 mg/day to 453 ± 198 at 12 months. Most OMERACT domains and renal function improved significantly; 73% improved > 20% from 6 to 12 months. Greater improvement was observed in the domains: flares, index tophus size, pain, general health assessment, and HAQ score, all of them associated to lower sUA values. Chronic gout patients improve significantly in most OMERACT domains when conventional and regular treatment is indicated. sUA < 6 mg/dL is associated with greater improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the last two decades, there have been important advances in gout knowledge and its understanding, from epidemiology to therapeutics. Gout, considered the most common arthropathy in young males, is associated with a number of comorbidities, including metabolic syndrome, kidney disease, and ischemic heart disease, all of which increase the risk of mortality in this population [1]. Today, there are new drugs and therapeutic strategies for the management of hyperuricemia, acute arthritis, and a number of additional clinical problems, including tophi, comorbidities, and drug-induced adverse events [2]. While acute gout is characterized by acute pain and swelling, the chronic stage is characterized by the development of tophi as well as structural, irreversible damage to the joints, [3].

In 2005, an Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) Gout Special Interest Group proposed a core set of domains to be considered in the evaluation of acute and long-term therapy for chronic gout, with a preliminary list of domains [4]. These domains were revised after the evaluation of previous publications and expert opinions. For acute gout, seven outcomes were initially considered essential. For chronic gout, several changes were proposed, with new outcomes being included, while others were renamed, changed, or removed. Following that revision, 10 domains remained after analysis and discussion; six were mandatory domains for acute gout and five discretionary for some studies. For chronic gout, seven domains were mandatory and 10 discretionary. Another domain was kept on the agenda for research, perhaps as a variable for some clinical trials [5].

Previous studies considered the technical properties of the instruments used for measurements in the context of the OMERACT filter of truth, discrimination, and feasibility. Other important items or domains, such as patient-reported outcomes, new and old drug safety and tolerability, economic issues as well as the possibility of developing a response index, have been proposed [5,6,7,8,9,10,11].

The aim of the current study was to determine the improvement of gout according to OMERACT domains when comparing baseline, 6-month, and 12-month follow-up data, as well as the percentage of patients that improved, the percentage of improvement, and the effect size in an inception cohort of new patients with gout referred to two rheumatology departments.

Methods

Patients

In 2010, the Gout Study Group (GRESGO) initiated a cohort of all consecutive, new patients with gout who were referred to either of two dedicated gout clinics at the rheumatology departments of the Hospital General de México Eduardo Liceaga and the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y de la Nutrición Salvador Zubirán in México City. All patients fulfilled previous criteria (American Rheumatism Association classification [12] and the Clinical Gout Diagnosis [13]) and in retrospect the American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria [14]. In addition, we observed monosodium urate crystals in the synovial fluid or tophi of 65% of the patients. Patients were referred straight from primary healthcare centers as well as by several specialists based at the institutions mentioned above. Unfortunately, none of such institutions provided medication to outpatients and despite that most of them were classified in the lowest income level, they had to rely on their own pocket to cover the cost of treatment.

Data collection followed the procedures of a protocol for both clinics. Baseline evaluation included demographic, educational, economical, and social variables; family history; clinical data; imaging studies (if needed); and laboratory tests. Additionally, we investigated previous treatments and medications at baseline. Patient management was determined by the treating physician.

For the analysis of this cohort, we considered 142 patients that attended the clinics between 2010 and 2012 and have both, baseline and 6-month evaluation. One hundred and one of those patients still attended to the clinic at the 12-month evaluation. By April 2017, there were 491 patients with gout in the GRESGO cohort.

Ethical considerations

The ethics and research committees of both centers approved the study protocol. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles contained in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were informed about the procedures of the study and provided written informed consent.

OMERACT domains

The seven OMEARCT mandatory domains and their definitions for chronic gout are as follows:

-

1.

Serum uric acid (sUA, mg/dL)

-

2.

Flares: the number of episodes of acute arthritis in the last 6 months

-

3.

Tophus burden: tophi number and index tophus size (ITS): the length (in cm) of the longest axis of the biggest accessible tophus

-

4.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL): by using the European Quality of Life (EQ-5D) questionnaire [15] which includes the following five factors: (a) mobility, (b) self-care, (c) daily activities, (d) pain/discomfort, and (e) anxiety/depression. The patient rates each factor as follows: 1 = no problem, 2 = some or moderate, 3 = severe or extreme impairment

-

5.

Activity limitations: by using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), adapted for gout [16] and the number of joints with limited mobility (44 joint count)

-

6.

Pain level: as marked in a 10-cm visual analog scale (Pain.VAS) from 0 (no pain at all) to 10 (extreme pain) and the number of tender joints

-

7.

Patient global assessment (PG.VAS): as marked in a 10-cm VAS from 0 (being very well) to 10 (being very bad)

Discretionary outcomes included in this evaluation were the number of swollen joints (SJ), work disability defined as the loss of a least 1 day of work because of gout in the last 6 months, and physician global assessment of health (PhGA.VAS): as marked in a 10-cm VAS of health from 0 (very well) to 10 (very bad). OMERACT domains and other variables were evaluated 6 and 12 months after baseline. Intermediate visits were scheduled according to each patient’s needs.

Comorbidities

We searched for past and current comorbidities based on the information provided by the physician that referred the case, by review of medical records, including current treatment, and through direct questioning and clinical evaluation of the patient in the clinic. In this way, we searched for vascular diseases, endocrinopathies, renal lithiasis, and peripheral nerve disease. We looked for components of the metabolic syndrome as defined by the Adult Treatment Panel III criteria [17]. All patients with at least three of the following five criteria were included in the metabolic syndrome patient group: (1) obesity: waist circumference > 102 cm in men and > 88 cm in women; (2) systemic hypertension: blood pressure > 130/85 mm or current anti-hypertensive therapy; (3) dyslipidemia: low high-density lipoprotein in men (≤ 40 mg/dL) and women (≤ 50 mg/dL); (4) triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL; and (5) hyperglycemia ≥ 110 mg/dL, diabetes mellitus [18], or previous American Association of Diabetes criteria.

Glomerular filtration rate was measured using 24-h urinary creatinine clearance and the Modification of Diet in Renal Diseases (MDRD) formula: glomerular filtration rate = 186 × (creatinine) − 1.154 (age) − 0.203 or (× 0.742 for women) [19]. The existence of chronic kidney disease was considered in patients with glomerular filtration rate of < 60 mL/min according to the KDIGO 2012: clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease (Table 1) [20].

Previous, baseline, and subsequent treatment

Before attending our clinic, most patients (95%) did not receive a proper treatment. Most of them took medications on their own demand; some did not take any medication. According to previous recommendations and the T2T strategy, we tried to reach a sUA value < 6 mg/dL as the main target. In this study, conventional treatment was determined by availability and included three important factors: (1) urate-lowering therapy particularly allopurinol regularization, (2) colchicine prophylaxis, and (3) in glucocorticoid-dependent patients, slow decrease until withdrawn (see below).

Patients were treated according to clinical symptoms and laboratory findings. Usually, the rheumatologist coordinated the treatment of comorbidities, including the consultations with other specialists to receive the standard treatment. The need for lifestyle modifications, including diet, exercise, and weight reduction and on the other hand, the importance of adherence to treatment was extensively discussed with patients and often with their close relatives [21, 22].

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and glucocorticoids

NSAID doses were those recommended in published guidelines. NSAIDs were prescribed on-demand to reduce joint pain with/without swelling. Diclofenac and indomethacin were the two NSAIDs most frequently prescribed.

Regarding glucocorticoids before baseline, half of the patients were on oral and/or parenteral glucocorticoids as result of self or wrong-prescription of compounds that very often consisted on a combination of dexamethasone or betamethasone. While some of the patients took glucocorticoids occasionally, others did it continuously (> 1 dose/week). Patients taking glucocorticoids rather than prednisone were switched to equivalent doses of such compound. The dose of prednisone was gradually reduced and eventually stopped according to clinical symptoms. It took around 8 months to completely withdraw the glucocorticoids. By months 6 and 12, the percentage of patients on glucocorticoids decreased significantly (Table 2).

Allopurinol and other urate-lowering therapies

Only two urate-lowering therapy (ULT) compounds were available in our country when we started this study: allopurinol and probenecid. Nearly all patients (97%) had a past or current history of inappropriate treatment, including the frequent use of low dose of allopurinol or no use at all during asymptomatic periods. At baseline, the mean dose of allopurinol we prescribed was > 300 mg/day. Based on sUA levels, the dose could be increased 6 or 12 months later (Table 2), and our target was sUA < 6 mg/dL. Only five patients had a history of hypersensitivity to allopurinol; the alternatives for these patients in 2012 were probenecid and/or desensitization to allopurinol (Table 2).

Colchicine

Colchicine is available in our country only as 1 mg tablets and was initiated in almost all patients as a prophylactic agent at baseline. If tolerated, colchicine was indicated for a longer period of time (Table 2).

Statistical analysis

Baseline data were compared with data collected at 6 and 12 months using chi squared and t tests, Wilcoxon tests, and Friedman analysis, as appropriate. Means, medians, or percentages between visits were compared, as well as percentage of change and effect size with the Cohen method [23]. A low effect was considered with a value < 0.2.

Results

Patients

General characteristics

Most patients were young males with long disease duration and frequent complications, such as functional and renal impairment and metabolic syndrome-associated diseases (Table 1). Overall, 30% of the patients in this cohort had metabolic syndrome. Twenty-nine percent of patients were lost through follow-up between the 6th and 12th month. However, the comparison of patients that completed the 12-month follow-up and those lost during 6- to 12-month period did not disclose any significant difference in demographic and clinical baseline variables, except for the number of tophi, which was lower in the patients lost to follow-up at baseline (median [IQR] 1.0 [0.0–5.0] VS 1.5 [0.0–9.25], p = 0.05).

Improvement in OMERACT variables

There was a significant improvement in most OMERACT domains 6 and 12 months after the baseline initiation of an adequate treatment. The percentage of improvement and the time to achieve that goal was variable. There was also a significant improvement in renal function (Table 3), but none of the components of metabolic syndrome improved (data not shown, previously published) [24].

Percentage of improvement in OMERACT variables

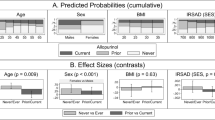

The percentage of patients that improved by 20, 50, and 70% in each domain at 6 and 12 months is shown in Fig. 1. The flares domain achieved the highest proportion of patients reaching an improvement of 20, 50, and 70% by 6 months. The number of tophi domain in combination with two other domains ranked the three bottom lines. Interestingly, the percentages of patients that reached 20% improvement showed a trend going from the highest to the lowest value. Results were certainly the same at the 12-month evaluation (Fig. 2). Yet, regarding 50 and 70% improvement, we did not observe such trend but an irregular tendency. The mobility domain was the function with most impairment in the EQ-5D questionnaire evaluation: 55% of the patients scored two and three at baseline and 46 and 33% at 6 and 12 months (Table 3).

We calculated the percentage of patients with > 20% improvement in > 1 OMERACT domains. Thus, 73% of the patients had > 20% improvement in two to six variables; on the contrary, four patients did not reach > 20% improvement in any variable; and finally, two patients showed > 20% in the nine domains included in this analysis.

Effect size

In rank order, the effect size for each variable was (1) flares, (2) Pain.VAS, (3) HAQ score, (4) sUA, and (5) PhG.VAS at 6 months. Rank order at 12 months was: (1) Pain.VAS, (2) PhG.VAS, (3) Flares, (4) PG.VAS, and (5) number of tender joints. The effect size for most variables was higher in the period between baseline and 12 months than in the period between baseline and 6 months (Fig. 2).

Further analysis

Five variables (Flares, ITS, PhG.VAS, HAQ, and Pain.VAS) seem to be the best measures for improvement; they coincide in the current study as those with higher percentage of patients with > 20% of improvement and greater effect size. Four of these variables are considered among OMERACT mandatory domains (PhG.VAS is a discretionary domain). Based on that, we did a further analysis and considered as “greater improvement” to the group of patients achieving ≥ 20% improvement in at least two of the following four variables for tophaceous gout: (1) Flares, (2) ITS, (3) HAQ, and (4) Pain.VAS. For non-tophaceous gout, we required two out of the same variables excepting ITS (Table 4).

More than a half of the patients (65%) fulfilled the greater improvement definition. Interestingly, the comparison of patients with and patients without greater improvement did not disclose any significant difference in demographic, clinical, or biochemical variables, except for sUA. As expected, sUA was clearly associated with ≥ 20% improvement from baseline to 6 and 12 months. Of the entire study population, 28 and 32% had sUA < 6 mg/dL at 6 and 12 months, respectively.

Discussion

This study evaluated the performance of the OMERACT domains for the evaluation of chronic gout in real clinical settings. We found that patients with gout, some of whom had the disease for a long time, showed significant improvement at 6 and 12 months in most OMERACT domains for chronic gout and in renal function after starting a proper conventional treatment. The number of flares, ITS, level of pain, and HAQ score showed the greatest improvement. In addition, low sUA levels at 6 and 12 months were associated with improvement.

In the current study, tophi number and the number of swollen joints did not change significantly during follow-up. We evaluated tophus burden as tophi number and ITS and found that ITS changes occurred earlier than the number of tophi would decrease [25, 26] although some tophi improved faster than others in the same patient. We found improvement in joints that had previously shown limited motion as well as in the HAQ scores. This may have been associated with the removal of sUA deposits.

Among the outcome measures for chronic gout proposed by OMERACT and recent studies [22, 25,26,27,28,29], maintaining sUA level < 6 mg/mL is considered the target outcome for long-term evaluation. The sUA level meets the OMERACT filter for truth, discrimination, and feasibility and has been proposed as a biochemical marker associated with improvement [26].

The percentage of patients that reached that target in this study was very low, specifically 28% at 6 and 32% at 12 months. A very recent study from Denmark found that 85% of a group of 100 patients with gout reached the sUA target 4.7 ± 3.9 months after starting a proper treatment [30]. Interestingly, only 15% of those patients were on sUA-lowering drugs at entry, and on the other hand, most patients in whom the target was not achieved have low compliance. The low percentages found in our study could be the result of the high tophus burden they have. Although the index of tophus size went down, the decrease of sUA level was slower. As we got close to sUA of 6 mg/dL, other variables, including renal function, improved.

Our study has some limitations: our patients may not be representative of the common patient with gout. However, the characteristics of our population look very similar to those with severe gout, the type of disease that occurs in patients from the lower socioeconomic levels in developing countries. Twenty-nine percent of the patients included in the study were lost to follow-up after the 6-month evaluation. Unfortunately, this happens frequently in gout, including clinical trials [31] and observational studies [32]. Regardless of patients attending the clinic, the low adherence of patients with gout seems associated with clinical characteristics of the disease, probably the long-term (months or years), inter-critical periods and particularly the evasive coping pattern that predominates among the gout patient population [33]. Another possible limitation of our study could be reference bias, since most of our patients have severe gout and few acute attacks or mild disease that responds well to therapy. Better responses may be achieved if other urate-lowering therapies and healthcare programs were available. The effect size observed in this study could be biased due to the number of patients lost to follow-up. This situation may limit the usage of other responsiveness measures as Guyatt’s index and minimal clinically detectable differences.

Although the severe form of the disease is associated with long-term, sub-optimal treatment, poor adherence to treatment, and the chronic glucocorticoid treatment [34], these patients may have a good response to treatment if they keep it for the time being necessary. There was no improvement or adverse events for metabolic variables particularly obesity, in the current study and our previous report [24].

Improvement of gout requires a multi-factor approach, but achieving sUA level < 6 mg/dL, and < 5 mg/dL in severe cases, is associated with a decrease in monosodium urate crystal deposits, clinical improvement, and better long-term outcome (chronic arthropathy and disability).

There is currently a discussion about treat-to-target VS treat-to-avoid symptoms for gout patients [35,36,37]. Treat-to-avoid is poorly defined, with a decrease of flares being an early and necessary goal, but it is not enough. Patients in the current study had received previously, irregular symptomatic treatment (to avoid symptoms). Subsequently, they present to our rheumatology departments with structural damage and advanced disease.

Gout patients, including those with severe long-standing disease, can improve significantly in most clinical outcomes with regular and adequate treatment. Intensive educational and promotional programs for gout knowledge are required for the general population, patients, general practitioners, and rheumatologists, in order that gout patients receive early diagnosis and adequate treatment. The implementation of these programs and more available treatment options for gout will influence general health, as well as labor and economic benefits.

References

Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Mallen C, Zhang W, Doherty M (2015) Rising burden of gout in the UK but continuing suboptimal management: a nationwide population study. Ann Rheum Dis 74:661–667

Wise E, Khanna PP (2015) The impact of gout guidelines. Curr Op Rheumatol 27:225–230

Dalbeth N, McQueen FM, Singh JA et al (2011) Tophus measurement as an outcome measure for clinical trials of chronic gout: progress and research priorities. J Rheumatol 38:1458–1461

Schumacher HR Jr, Edwards LN, Perez-Ruiz F et al (2005) OMERACT 7 special interest group. Outcome measures for acute and chronic gout. J Rheumatol 32:2452–2455

Taylor WJ, Schumacher HR Jr, Baraf HS et al (2008) A modified Delphi exercise to determine the extent of consensus with OMERACT outcome domains for studies of acute and chronic gout. Ann Rheum Dis 67:888–891

Schumacher HR, Taylor W, Joseph-Ridge N, Perez-Ruiz F, Chen LX, Schlesinger N, Khanna D, Furst DE, Becker MA, Dalbeth N, Edwards NL (2007) Outcome evaluations in gout. J Rheumatol 34:1381–1385

Schumacher HR, Taylor W, Edwards L et al (2009) Outcome domains for studies of acute and chronic gout. J Rheumatol 36:342–345

Singh JA, Taylor WJ, Simon LS et al (2011) Patient-reported outcomes in chronic gout: a report from OMERACT 10. J Rheumatol 38:1452–1457

Taylor WJ, Singh JA, Saag KG et al (2011) Bringing it all together: a novel approach to the development of response criteria for chronic gout clinical trials. J Rheumatol 38:1467–1470

Taylor WJ, Brown M, Aati O, Weatherall M, Dalbeth N (2013) Do patient preferences for core outcome domains for chronic gout studies support the validity of composite response criteria? Arthritis Care Res 65:1259–1264

Diaz-Torne C, Pou MA, Castellvi I, Corominas H, Taylor WJ (2014) Concerns of patients with gout are incompletely captured by OMERACT-endorsed domains of measurement for chronic gout studies. J Clin Rheumatol 20:138–140

Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, Decker JL, McCarty DJ, Yü TF (1977) Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum 20:895–900

Vázquez-Mellado J, Hernández-Cuevas CB, Alvarez-Hernández E, Ventura-Rios L, Peláez-Ballestas I, Casasola-Vargas J, García-Méndez S, Burgos-Vargas R (2012) The diagnostic value of the proposal for clinical gout diagnosis (CGD). Clin Rheumatol 31:429–434

Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N et al (2015) 2015 gout classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol 67:2557–2568

Herdman M, Badía X, Berra S (2001) EuroQol-5D: a simple alternative for measuring health-related quality of life in primary care. Aten Primaria 28:425–430

Alvarez-Hernández E, Peláez-Ballestas I, Vázquez-Mellado J et al (2008) Validation of the health assessment questionnaire disability index in patients with gout. Arthritis Rheum 15:665–669

Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (2001) Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III). JAMA 285:2486–2497

Marathe PH, Gao HX, Close KL (2017) American Diabetes Association standards of medical Care in Diabetes 2017. J Diabetes 9:320–324

Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D (1999) A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of diet in renal disease study group. Ann Intern Med 130:461–470

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group (2012) KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3:1–150

Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, Bae S, Singh MK, Neogi T, Pillinger MH, Merill J, Lee S, Prakash S, Kaldas M, Gogia M, Perez-Ruiz F, Taylor W, Lioté F, Choi H, Singh JA, Dalbeth N, Kaplan S, Niyyar V, Jones D, Yarows SA, Roessler B, Kerr G, King C, Levy G, Furst DE, Edwards NL, Mandell B, Schumacher HR, Robbins M, Wenger N, Terkeltaub R, American College of Rheumatology (2012) 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res 64:1431–1446

Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, Barskova V, Becce F, Castañeda-Sanabria J, Coyfish M, Guillo S, Jansen TL, Janssens H, Lioté F, Mallen C, Nuki G, Perez-Ruiz F, Pimentao J, Punzi L, Pywell T, So A, Tausche AK, Uhlig T, Zavada J, Zhang W, Tubach F, Bardin T (2017) 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 76:29–42

Husted JA, Cook RJ, Farewell VT, Gladman D (2000) Methods for assessing responsiveness a critical review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol 53:459–468

García-Méndez S, Rivera-Bahena CB, Montiel-Hernández JL et al (2015) A Prospective follow-up of adipocytokines in cohort patients with gout. Association with metabolic syndrome but not with clinical inflammatory findings: strobe-compliant article. Medicine 94:e935

Pérez Ruiz F, Atxotegi J, Hernado I, Calabozo M, Nolla JM (2006) Using serum urate levels to determine the period free of gout symptoms after withdrawal of long-term urate-lowering therapy: a prospective study. Arthritis Rheum 55:786–790

Perez Ruiz F, Lioté F (2007) Lowering serum uric acid levels: what is the optimal target for improving clinical outcomes in gout? Arthritis Rheum 57:1324–1328

Pascual E, Andrés M, Vela P (2013) Gout treatment: should we aim for rapid crystal dissolution? Ann Rheum Dis 72:635–637

Stamp LK, Khanna PJ, Dalbeth N et al (2011) Serum urate in chronic gout—will it be the first validated soluble biomarker in rheumatology? J Rheumatol 38:1462–2466

Corbett EJ, Pentony P, McGill NW (2017) Achieving serum urate targets in gout and audit in a gout-oriented rheumatology practice. Int J Rheum Dis 20:894–897

Slot O (2017) Gout in a rheumatology clinic: results of EULAR/ACR guidelines compliant treatment. Scand J Rheumatol 11:1–4

Saag K, Fitz-Patrick D, Kopicko J et al (2017) Lesinurad combined with allopurinol: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in gout patients with an inadequate response to standard-of-care allopurinol (a US-based study). Arthritis Rheumatol 69:203–212

Hughes JC, Wallace JL, Bryant CL, Salvig BE, Fourakre TN, Stone WJ (2017) Monitoring of Urate-lowering therapy among US veterans following the 2012 American College of Rheumatology Guidelines for Management of Gout. Ann Pharmacother 51:301–306

Peláez-Ballestas I, Boonen A, Vázquez-Mellado J et al (2015) Coping strategies for health and daily-life stressors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and gout: STROBE-compliant article. REUMAIMPACT Group Med 94:e600

López López CO, Lugo EF, Alvarez-Hernández E, Peláez-Ballestas I, Burgos-Vargas R, Vázquez-Mellado J (2017) Severe tophaceous gout and disability: changes in the past 15 years. Clin Rheumatol 36:199–204

Kiltz U, Smolen J, Bardin T, Cohen Solal A, Dalbeth N, Doherty M, Engel B, Flader C, Kay J, Matsuoka M, Perez-Ruiz F, da Rocha Castelar-Pinheiro G, Saag K, So A, Vazquez Mellado J, Weisman M, Westhoff TH, Yamanaka H, Braun J (2017) Treat to target (T2T) recommendations for gout. Ann Rheum Dis 76:632–638

Shekelle PG, Newberry J, Fitzgerald JD et al (2017) Management of gout: a systematic review in support of an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med 166:37–51

Fitzgerald JD, Neogi T, Choi HK (2017) Editorial: do not let gout apathy lead to gouty arthropathy. Arthritis Rheumatol 69:479–482

Acknowledgements

We thank Aarón Vazquez Mellado MO and Ma. Eugenia Sanchez Girard as research assistants for the GRESGO cohort.

Funding

This project received unrestricted partial financial support from Unidad de Investigación, Colegio Mexicano de Reumatología; Servicio de Reumatología and Dirección de Investigación, Hospital General de México and Takeda, México.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The ethics and research committees of both centers approved the study protocol. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles contained in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were informed about the procedures of the study and provided written informed consent.

Disclosures

None.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(XLSX 14 kb).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vazquez-Mellado, J., Peláez-Ballestas, I., Burgos-Vargas, R. et al. Improvement in OMERACT domains and renal function with regular treatment for gout: a 12-month follow-up cohort study. Clin Rheumatol 37, 1885–1894 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4065-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4065-7