Abstract

Background

Inguinal hernias are the most common operative procedure performed by general surgeons, and tension-free mesh techniques have revolutionized the procedure. While hernia recurrence rates have decreased, chronic postoperative pain has become recognized more widely. New mesh products offer the potential to decrease pain without compromising recurrence rates. Polyester mesh is a softer material than traditional polypropylene and may offer the benefit of causing less postoperative pain and improved quality of life.

Methods

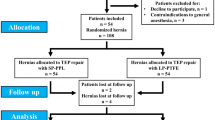

Prospective, single-blind, randomized controlled trial involving 78 patients assigned to receive Lichtenstein type repair with either polyester (n = 39) or polypropylene (n = 39) mesh. Attempt was made to identify ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genitofemoral nerves intraoperatively and document their handling. Patients were interviewed and examined preoperatively and postoperatively at 2 weeks and 3 months. Inguinal Pain Questionnaire (IPQ) and VAS scores were obtained and analyzed using two sample t test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables.

Results

VAS scores at 3 months were 0.46 for the polyester group versus 0.56 for the polypropylene group (P = 0.6727). At 3 months, 82.3% of the polyester and 76.4% of the polypropylene group had VAS = 0 (P = 0.5486). There was no significant difference between the two groups’ VAS scores at 3 months. IPQ did not show any difference between the two groups with the exception of “catching or pulling” being reported in 34.3% of polyester and 5.7% of polypropylene groups (P = 0.0028).

Conclusions

Polyester mesh does not decrease the amount of chronic pain at 3 months. Outcomes with polyester mesh are comparable to polypropylene mesh for Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair with regards to postoperative pain and quality of life. The sample size in this study was small and limits the significance of the results. Further studies are needed to find the optimal mesh for inguinal hernia repair.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inguinal hernia repair is the most common general surgery procedure, and several hundred thousand are performed every year in the United States. Countless studies have been done in attempts to improve outcomes, and the procedure has evolved greatly, especially over the last few decades. Hernia recurrence was a significant problem in the past; however, with the advent of the tension-free mesh repair as described by Lichtenstein and colleagues [1], recurrence rates have dropped significantly and are consistently reported as 1–10% [2–6]. Concomitant with this drop in recurrence, researchers and clinicians have noted an increase in the rate of chronic pain following hernia repair.

The definition of chronic pain, as set forth by the International Association for the Study of Pain, and referenced by Poobalan et al. [7], is pain that persists at the surgical site and nearby surrounding tissues beyond 3 months. Despite the frequency with which the procedure is performed and the extensive research that has been done, chronic postoperative pain continues to be a significant problem in inguinal herniorraphy. Multiple studies have been performed documenting the pain associated with inguinal hernia repair. The incidence of chronic pain has been reported to range from 13% up to 57% of subjects, depending on the study and level of severity of the pain studied [2, 7–14].

Unlike some surgical diseases, which disproportionately affect the elderly population, inguinal hernia is a problem that affects young and middle aged adult populations as well as the elderly. Studies have shown that younger patients undergoing herniorrhaphy experience more postoperative pain than elderly patients [7, 11, 15]. Given that a fair number of the annual hernia repairs are preformed on active, productive adults, the societal costs in terms of lost productivity due to postoperative pain and missed work are potentially great. Additionally, more than 50% of patients reported that their postoperative pain affected their social activities [11, 15].

Polyester mesh is a soft, pliable, lightweight material that has recently been introduced in the United States for use in hernia repair. Studies using polyester mesh have been limited thus far to laparoscopic inguinal and incisional hernia repairs [3, 16]. The published results of these studies are favorable, with side effect and complication rates comparable to standard practice, i.e., approximately 7–12% [3–6, 16, 17]. However, no comparison study between polyester and polypropylene mesh used in open inguinal hernia repairs has been performed. Polyester mesh has been shown to incite an early, intense inflammatory reaction that stimulates greater tissue ingrowth and integration. Along with this higher degree of connective tissue integration, it has less mesh contraction, less fibrous encapsulation, and less stiffness around the mesh than polypropylene mesh [18]. With better tissue integration, less encapsulation, and less contraction, the sensory nerves of the groin may potentially be less affected—less likely to be pulled or stretched, less likely to be in a field of a chronic inflammatory reaction, or less likely to be constantly irritated by a firm piece of mesh or capsule surrounding the mesh—translating into less chronic pain. Implanted prosthetic meshes used in hernia repairs are much stronger than they need to be to resist intraabdominal pressures. A recent study [19] showed the tensile strength of the polypropylene mesh to be more than five times stronger than the native abdominal wall. While there may be concerns over the strength of the lighter-weight polyester meshes, the tensile strength of polyester mesh was shown to be approximately four times stronger than maximum intraabdominal pressure (Tensile strength of Parietex mesh. Personal communication from Matt Thomas, AutoSuture/United States Surgical. 16 July 2006).

Given the aforementioned properties, polyester mesh has the potential to be a suitable alternative to polypropylene mesh, and may offer improvements in terms of pain and postoperative quality of life.

Methods

Approval for the proposed study was obtained from the local Institutional Review Board. Seventy-eight patients were enrolled prospectively in the study through the outpatient clinic, and were randomized to undergo standard anterior Lichtenstein hernia repair with either “heavyweight” polypropylene mesh or polyester mesh. Patients were blinded to the mesh they received and remained blinded throughout the follow-up period. Patients were 18 years old or older, not pregnant, had no previous history of anterior mesh hernia repair on the planned operative side, had no other concomitant surgical procedures planned, and were cognitively able to discuss the study. All underwent elective inguinal hernia repairs.

The study was conducted as a part of the Scott & White Outcomes and Effectiveness Research Group—a program for performing effectiveness studies comparing the effectiveness of different treatments in the course of usual clinical care. Effectiveness studies are designed to evaluate outcomes of care in realistic practice situations, in contrast to efficacy studies performed in highly selected populations under ideal conditions [20–22].

Subjects were given a study folder that included copies of the VAS (visual analog scale) [23], the Inguinal Pain Questionnaire (IPQ) [24], and several surgery-specific questions created by the investigators based on common complaints listed in previous research [8, 15] (see “Appendix” for these instruments). Both the VAS and IPQ have been previously validated [23, 24]. These three measurement tools were to be completed by patients at 2 weeks, and 3, 12, and 24 months. A research nurse coordinator called study patients to collect this data. If the follow-up call dates fell on a weekend or holiday, the subject was called on the next business day. At any time postoperatively, if the patient reported a possible hernia recurrence, intractable nausea/vomiting/pain, or signs/symptoms of a wound infection or other complication, he or she was scheduled for an office visit evaluation. At the clinic visit approximately 14 days after surgery (the only routinely scheduled visit), study patients were instructed that they could return to full activity. This visit could be ±7 days of the 14 day visit, at the discretion of the operating surgeon. All subjects were given a prescription for 30 tablets of hydrocodone/APAP 5/500. Those with an allergy or intolerance of hydrocodone/APAP were given a similar prescription for propoxyphene/APAP.

Self assessment schedule

Instrument | Preoperative | 2 weeks | 3 months | 1 year | 2 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

VAS | X | X | X | X | X |

IPQ | X | X | X | X | |

Surgery specific questions | X | X | X | X |

The primary endpoint was chronic pain (measured by VAS) and effect on lifestyle (measured by IPQ) at 3 months; secondary endpoints included operative and anesthesia time, duration of hospital stay or postoperative stay, degree of pain at 2 weeks, and at 12 and 24 months, hernia recurrence, and other complications such as infection, hematoma, seroma, need for readmission.

Intra-operative and/or post-operative adverse events were managed, documented, and reported appropriately. For any patient who developed chronic groin pain related to the surgery, the surgeon managed this complication. Possible treatments for chronic pain included long-term narcotic pain medication, other prescription medications accepted as treatment for chronic non-nociceptive pain (e.g., amitriptyline, gabapentin, pregabalin), nerve blocks by members of the anesthesia department, referral to the pain clinic run by the department of anesthesiology, or reoperation with possible neurolysis or removal of mesh.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of the study participants were summarized using descriptive statistics for two groups, and differences assessed using two-sample t test for continuous data and either chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. If data were strongly skewed, the Wilcoxon or other appropriate non-parametric tests was used. All statistical comparisons were made using 0.05 level of significance. SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analysis.

Sample size and power analysis

The reported incidence of postoperative pain at 3 months following hernia repair using the polypropylene mesh (our control) was 0.57 [7]. The sample size required to detect a benefit for the new mesh of 25% reduction in pain at 3 months following hernia repair (from 57% to 32% of patients), with alpha 0.05 and power 90 is a minimum of 81 randomized patients per group. The accrual goal was increased to 85 per group to account for dropouts.

Results

A total of 78 patients were enrolled and randomized to receive either polyester or polypropylene mesh, with 39 in each group. One patient received polypropylene mesh instead of polyester which was their original randomized allocation. This patient was included in the polyester mesh group for intention to treat (ITT) analysis and in the polypropylene mesh group for per protocol analysis. Preoperative demographics were similar, with no statistical differences in terms of gender, age, lifting in current job, previous anterior hernia repair, or VAS score (Table 1).

The two groups were also similar with respect to intraoperative variables. The majority of both groups underwent repair under general anesthesia. Anesthesia time for the groups was 118 min for polyester and 125 min for polypropylene repairs (difference not statistically significant). Operative times were also statistically equivalent, with polyester repairs lasting on average 77 min and polypropylene repairs lasting 88 min (Table 2).

There was no difference in rate of admission to the hospital, incision length, defect type, or rate of identification of ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, or genitofemoral nerves. There was a statistically higher rate of iliohypogastric nerve division in the polypropylene group, with 11% nerve transection rate in the polyester group and 32% transection rate in the polyester group. Rates of nerve transection of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves were equivalent (Table 3).

Of the initial 78 patients, 77 completed the 2-week follow-up (one patient in the polypropylene group did not), and 70 (35 patients from each group) completed the 3 month follow-up. At 2 weeks, the mean ± SD VAS score in the polyester group was 1.18 ± 1.42, and the mean VAS score for the polypropylene group was 1.39 ± 1.36 (P = 0.4989). When the patients are dichotomized into groups of those with any pain (VAS > 0) and those with no pain (VAS = 0), there remains no statistical difference between the two mesh products, with equal numbers of patients having some pain at 2 weeks (P = 0.2821). At 3 months, the mean VAS score in the polyester group was 0.46 ± 1.22, and in the polypropylene group was 0.56 ± 1.13 (P = 0.7213). When patients are dichotomized into those with any remaining pain and those with no pain at 3 months, there is no significant difference between the two mesh products (P = 0.5486) (Tables 4, 5).

At 2 weeks, reporting rates for author-created pain descriptors were equivalent between the two groups. There was no statistical difference in complaints of “throbbing, stabbing, aching, or burning,” “catching, pulling, tugging, or tearing,” or “numbness or dullness” (all P > 0.1). This equivalence remained after dichotomizing reports into “any complaint” versus “no complaints” (all P > 0.1). There was no difference in the rate of patients reporting performing some activities more slowly, with about 90% of both groups affirming this. An equivalent number of patients reported being unable to perform some activities due to pain. There were no recurrences in either of the two groups. There were three complications in the polyester group, and one in the polypropylene group in the first 2 postoperative weeks. Complications included hematoma, rash, chest pain and dyspnea, urinary retention, and dizziness with syncope. Each group had two hospitalizations, which occurred due to the following problems: respiratory insufficiency, hypotension with bradycardia, chest pain and dyspnea, and dizziness with syncope (Table 6).

At 3 months, reporting rates for complaints of “throbbing, stabbing, aching, or burning,” and “numbness or dullness” were equivalent (P > 0.4). This equivalence remained after dichotomizing reports into “any complaint” versus “no complaints” (P > 0.1). In contrast to the 2-week data, at 3 months, there were statistically more complaints of “catching, pulling, tugging, or tearing” in the polyester group than in the polypropylene group (P = 0.0189). The statistical significance remained after dichotomizing the patients into “any complaint” versus “no complaint” (P = 0.0028). There was no difference in the rate of patients reporting performing some activities more slowly, with about 15% of both groups affirming this. An equivalent number of patients reported being unable to perform some activities due to pain. There were no recurrences in either of the two groups. There were three complications in the polyester group and one in the polypropylene group between the 2 week and 3 month follow-ups. Complications included erectile dysfunction, osteitis pubis, abdominal wall strain, and postoperative pain requiring referral to pain clinic. There were no new hospital admissions in this follow-up period (Table 7).

Table 8 shows a breakdown of responses to the IPQ completed at 3 months. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups on any of the questions.

In the majority of patients, the ilioinguinal nerve was identified. The nerve was identified and protected in 45 patients, identified and divided in 28 patients, and not identified in 4 patients. The mean ± SD VAS score in patients whose ilioinguinal nerve was protected was 0.64 ± 1.43 at 3 months. The pain score in patients whose ilioingunal nerve was divided was 0.50 ± 1.09, and the mean pain score in those who the nerve was not identified was 0. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups with respect to mean pain score (P = 0.5594). When the groups are dichotomized into “any pain” versus “no pain,” the complaint rates between those with divided nerves is statistically equivalent to those with preserved nerves (P = 0.7971) (Table 9).

The iliohypogastric nerve was identified and protected in 27 patients, identified and divided in 16 patients, and not identified in 32 patients. The mean ± SD VAS score in patients whose iliohypogastric nerve was protected was 0.22 ±0.68 at 3 months. The pain score in patients whose iliohypogastric nerve was divided was 0.81 ± 1.58, and the mean pain score in those who the nerve was not identified was 0.68 ± 1.33. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups with respect to mean pain score (P = 0.2448). When the groups are dichotomized into “any pain” versus “no pain,” the complaint rates between those with divided nerves is statistically equivalent to those with preserved nerves (P = 0.2643) (Table 10).

The genitofemoral nerve was identified infrequently on patients in this study, being identified and protected in 5 patients, identified and divided in 7 patients, and not identified in 55 patients. The mean ± SD VAS score in patients whose genitofemoral nerve was protected was 0.51 ± 0.71 at 3 months. The pain score in patients whose genitofemoral nerve was divided was 1.14 ± 2.04, and the mean pain score in those who the nerve was not identified was 0.45 ± 1.08. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups with respect to mean pain score (P = 0.2448). When the groups are dichotomized into “any pain” versus “no pain,” the complaint rates between those with divided nerves is statistically equivalent to those with preserved nerves (P = 0.2643) (Table 11).

Discussion

Hernia repairs were first described by Bassini in the late 1800s, and an innumerable list of unique techniques have been developed and described. Almost 100 years after Bassini’s description, Lichtenstein’s repair was described, and his tension-free open inguinal hernia repair with onlay mesh is arguably the current standard of care. Great progress has been made with respect to recurrence rates, which were initially very high. Unfortunately, chronic pain following inguinal herniorrhaphy is now seen frequently; this problem continues to frustrate surgeons, with little progress being made over the last few decades, despite new techniques and materials.

In this study, polyester mesh was compared to standard polypropylene mesh in Lichtenstein herniorrhaphy. The study was single-blinded and randomized, performed in an effectiveness study format, which aims to compare results that would be expected in real-world practice. We employed commonly used and validated outcomes measures to evaluate pain and effect on quality of life. Groups were well-matched through the randomization process. The premise was that subjectively softer mesh material would cause less postoperative discomfort.

Patients were well-matched, with average ages, employment type, activity level, non-mesh repair, preoperative pain scores, incision length, and defect type being statistically equivalent. None of the preoperatively measured variables should confound the data or conclusions. Duration of operation and time under anesthesia were similar. Operative time was slightly longer than 1 hour, and time under anesthesia was about 2 h. While these times may be longer than those of other operators, they are likely reflective of the fact that the study was performed at a teaching institution, where residents of varying levels assisted on cases. Similarly, the majority of the cases were performed under general anesthesia. While this finding is unlikely to be representative of general clinical practice in the United States today, it is again likely related to the cases being performed at a teaching institution. The more relaxed atmosphere of a procedure under general anesthesia, lack of patient movement, and opportunity to provide more instruction to the trainee are all benefits of performing this procedure with general anesthesia.

Several studies have shown that handling of ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genitofemoral nerves may affect postoperative pain, with one study showing a benefit to routine division of the ilioinguinal nerve [25]. Understanding that there is reluctance to adopt routine neurectomy, even though it is an accepted treatment for chronic inguinodynia, our study did not dictate how nerves should be handled but rather attempted to describe how they were handled. Ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerve identification and division rates were similar between the polyester and polypropylene groups. At 3 months, there were no statistical differences between the pain scores of the group that had the nerves preserved compared to the group that had the nerves divided. However, there were statistically more iliohypogastric nerves divided in the polyester mesh group. This did not translate into any difference in mean pain scores nor in frequency of pain complaints at 3 months. We feel that this analysis negates or minimizes the pre-analysis difference between the two groups. The equivalence in postoperative pain despite different rates of iliohypogastric nerves should not be taken as evidence to support this practice, as our study population was small, and the study was not specifically designed to evaluate this outcome. Studies designed to elucidate the effects of routine iliohypogastric nerve division on postoperative pain and discomfort have not been performed.

There were no statistical differences between reported VAS pain scores between the two groups. Additionally, when looking at those reporting any pain at all, no difference in rates were seen at both 2 weeks and 3 months postoperatively. Researcher-designed pain questions showed no differences at 4 weeks, but did show increased complaints of “catching, pulling, tugging, or tearing” pain in the polyester group at 3 months. In explaining this difference, we return to the fact that in vitro studies have shown a vigorous inflammatory reaction around polyester, as opposed to the encapsulation that forms around polypropylene. The inflammatory reaction may involve more surrounding tissue and create the pulling or tugging sensation in the groin of these patients.

The validated IPQ asks detailed questions regarding common pain and discomfort complaints following inguinal herniorrhaphy and offers more detail about discomfort that the numeric VAS. There were no differences between the two mesh groups for any of the IPQ questions.

This study was not able to achieve the enrollment goals set forth in our study design protocol due to funding limitations. Overall enrollment was about half of the proposed goal. Given this smaller than planned size, there is significant possibility of type II (beta) error, or failure to reject a null hypothesis. Thus, any findings of equivalence between the mesh products may have been a failure to identify a difference. However, one may conclude from our study that there is an absence of large, highly significant differences between the two mesh products, but our study size was insufficient to detect small differences between the groups. In this regard, further study is needed to confirm our findings.

Conclusion

Compared to standard polypropylene mesh, polyester mesh placed in open inguinal hernia repair does not reduce postoperative pain or discomfort significantly, nor does it improve quality of life as measured by a standardized questionnaire. There are slightly higher rates of some types of pain complaints with the polyester mesh at 3 months. While polyester mesh appears to be a comparable alternative to polypropylene, it cannot be recommended over polypropylene. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings and to find the optimal mesh for inguinal hernia repair.

References

Amid PK (2004) Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty: its inception, evolution, and principles. Hernia 8(1):1–7

Heikkinen T, Bringman S, Ohtonen P, Kunelius P, Haukipuro K, Kulkko A (2004) Five-year outcome of laparoscopic and Lichtenstein hernioplasties. Surg Endosc 18(3):518–522

Lepere M, Benchetrit S, Debaert M, Detruit B, Dufiho A, Gaujoux D, Lagoutte J, Saint Leon LM, Parvis d’Escurac X, Rico E, Sorrentino J, Therin M (2000) A multicentric comparison of transabdominal versus totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic hernia repair using PARIETEX meshes. JSLS 4(2):147–153

Olmi S, Erba L, Magnone S, Bertolini A, Mastropasqua E, Perego P, Massimini D, Zanandrea G, Russo R, Croce E (2005) Prospective study of laparoscopic treatment of incisional hernia by means of the use of composite mesh: indications, complications, mesh fixation materials, and results (in Italian). Chir Ital 57(6):709–716

MacFadyen BV Jr, Mathis CR (1994) Inguinal herniorrhaphy: complications and recurrences. Semin Laparosc Surg 1(2):128–140

McCormack K, Scott NW, Go PM, Ross S, Grant AM (2003) Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair Cochrane Database (1):CD001785

Poobalan AS, Bruce J, King PM, Chamgers WA, Krukowski ZH, Smith WC (2001) Chronic pain and quality of life following open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 88(8):1122–1126

Poobalan AS, Bruce J, Smith WC, King PM, Krukowski ZH, Chambers WA (2003) A review of chronic pain after inguinal herniorrhaphy. Clin J Pain 19(1):48–54

Kumar S, Wilson RG, Nixon SJ, Macintyre IM (2002) Chronic pain after laparoscopic and open mesh repair of groin hernia. Br J Surg 89(11):1476–1479

Nienhuijs SW, van Oort I, Keemers-Gels ME, Strobbe LJ, Rosman C (2005) Randomized trial comparing the prolene hernia system, mesh plug repair, and Lichtenstein method for open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 92(4):33–38

Bay-Nielsen M, Nilsson E, Nordin P, Kehlet H (2004) Chronic pain after open mesh and sutured repair of indirect inguinal hernia in young males. Br J Surg 91(10):1372–1376

Koniger J, Redecke J, Butters M (2004) Chronic pain after hernia repair: a randomized trial comparing Shouldice, Lichtenstein, and TAPP. Langenbecks Arch Surg 389(5):361–365

O’Dwyer PJ, Kingsnorth AN, Molloy RG, Small PK, Lammers B, Horeyseck G (2005) Randomized clinical trial assessing impact of a lightweight or heavyweight mesh on chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 92:166–170

O’Dwyer PJ, Alani A, McConnachie A (2005) Groin hernia repair: postherniorrhaphy pain. World J Surg 29:1062–1065

Nienhuijs SW, Boelens OB, Strobbe LJ (2005) Pain after anterior hernia repairs. J Am Coll Surg 200(6):885–889

Ammaturo C, Bassi G (2004) Surgical treatment of large incisional hernias with intraperitoneal parietex composite mesh: our preliminary experience on 26 cases. Hernia 8(3):242–246

Ramshaw B, Abaid F, Voeller G, Wilson R, Mason E (2003) Polyester (Parietex) mesh for total extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Surg Endosc 17(3):498–501

Gonzales R, Ramshaw BJ (2003) Comparison of tissue integration between polyester and polypropylene prostheses in the preperitoneal space. Am Surg 69(6):471–476

Cingi A, Manukyan MN, Gulluoglu BM, Barlas A, Yegen C, Yalin R, Yilmaz N, Aktan AO (2005) Use of resterilzed polypropylene mesh in inguinal hernia repair: a prospective, randomized study. J Am Coll Surg 201(6):834–840

Hillis A, Rajab MH, Baisden CE, Villamaria FJ et al (1998) Three years of experience with prospective randomized effectiveness studies. Control Clin Trials 19:419–426

Rajab MH, Ashley P, Ogburn-Russell L, Baisden CE, Villarmaria FJ (1999) The effectiveness registry: an expansion of the tumor registry. J Registry Manag 26(3):99–101

Epstein RS, Sherwood LM (1996) From outcomes research to disease management: a guide for the perplexed. Ann Intern Med 124:832–883

Gallagher EJ, Biijur PE, Latimer C, Silver W (2002) Reliability and validity of a visual scale for acute abdominal pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 20(4):287–290

Franneby U, Gunnarsson U, Andersson M, Heuman R, Nordin P, Nyren O, Sandblom G (2008) Validation of an inguinal pain questionnnaire for assessment of chronic pain after groin hernia repair. Br J Surg 95(4):488–493

Mui W, Ng C, Fung T, Cheung F, Ma T, Bn M, Ng E (2006) Prophylactic ilioinguinal neurectomy in open inguinal hernia. Ann Surg 244(1):27–33

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Inguinal Pain Questionnaire

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sadowski, B., Rodriguez, J., Symmonds, R. et al. Comparison of polypropylene versus polyester mesh in the Lichtenstein hernia repair with respect to chronic pain and discomfort. Hernia 15, 643–654 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-011-0841-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-011-0841-x