Abstract

Introduction

Chronic pain after hernia repair is common, and it is unclear to what extent the different operation techniques influence its incidence. The aim of the present study was to compare the three major standardized techniques of hernia repair with regard to postoperative pain.

Patients and methods

Two hundred and eighty male patients with primary hernias were prospectively, randomly selected to undergo Shouldice, tension-free Lichtenstein or laparoscopic transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) hernioplasty repairs. Patients were examined after 52 months with emphasis on chronic pain and its limitations to their quality of life.

Results

Chronic pain was present in 36% of patients after Shouldice repair, in 31% after Lichtenstein repair and in 15% after TAPP repair. Pain correlated with physical strain in 25% of patients after Shouldice, in 20% after Lichtenstein and in 11% after TAPP repair. Limitations to daily life, leisure activities and sports occurred in 14% of patients after Shouldice, 13% after Lichtenstein and 2.4% after TAPP repair.

Conclusion

Chronic pain after hernia surgery is significantly more common with the open approach to the groin by Shouldice and Lichtenstein methods. The presence of the prosthetic mesh was not associated with significant postoperative complaints. The TAPP repair represents the most effective approach of the three techniques in the hands of an experienced surgeon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hernia repair is one of the most common surgical procedures, and postoperative recovery is uncomplicated in most patients. The introduction of the tension-free techniques has led to very low recurrence rates and such techniques seem to produce postoperative pain less frequently [1–3]. Some patients, however, fail to arrive at a complete reconstitution after surgery and suffer from chronic discomfort and pain [4].

The incidence of chronic pain following hernia repair is not accurately known. Different studies report frequencies of up to 40%, but observational methods vary, and prospective studies are few [4–8].

There is much speculation about the cause of chronic pain after hernia surgery, and several risk factors have been identified, such as recurrence, patient’s age and resection of the cremasteric muscle, experience of the surgeon and the presence of pre-operative pain. The influence, however, of different surgical techniques remains unclear [3, 4, 9–24].

Dissection of the groin by an anterior approach is more traumatic than the laparoscopic approach. Both open techniques, Shouldice and Lichtenstein, are associated with possible injury to peripheral nerve structures and scarring of the abdominal wall [25]. Nerve injury during laparoscopic hernia repair, especially to the nervus cutaneus femoris lateralis has also been reported, especially at the beginning of the laparoscopic repair era, but seems to be avoidable with the correct operating technique [21]. Tension-free techniques and especially laparoscopic repair, seem to be less painful in the early postoperative period [3, 12, 26], but there is no evidence as to whether the presence of the prosthetic mesh itself may be the source of postoperative complaints [3, 22, 27–29].

In this study, the patients were randomly assigned to three different groups and were operated on by Shouldice, Lichtenstein or laparoscopic transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) techniques. Follow-up occurred within 52 months. Attention focused on development of chronic pain and its influence on patients’ physical endurance and their quality of life.

Patients and methods

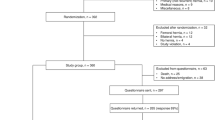

In a time interval of 12 months 280 male patients with primary hernias were selected and randomly assigned to three different groups. Informed consent was taken from all the patients before surgery. Randomization was by sealed envelope. The groups were matched by age and body mass index (Table 1). Ninety-three patients in group 1 were operated on by the Shouldice technique [30], 93 patients (group 2) by the tension-free Lichtenstein technique [31] and 94 patients (group 3) by the laparoscopic TAPP technique [32]. The patients were operated on by three surgeons experienced in both conventional and laparoscopic techniques (>100 TAPP, Lichtenstein and Shouldice interventions each). Mesh fixation in the laparoscopic group was performed with between four and six titanium clips (EMS Herniostate; Ethicon) with strict avoidance of clips in the area distal of the ileopubic tract. In the case of the Lichtenstein technique the mesh was fixed with a running suture (4/0 Prolene) to the inguinal ligament. All patients were operated on under general anaesthesia and received one dose of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid preoperatively. Patients were followed within a median of 52 months (range 46–60) in face-to-face interview by a surgical resident. Attrition was 15.7%: 15 patients died of unrelated causes, and 28 patients moved to unknown addresses or would not participate.

The patients were assessed for intensity, character and frequency of discomfort and pain, pain associated with physical strain and for limitations to daily life and physical activities. A standardized interview form was used to obtain objective and comparable results (Table 2). A visual analogue scale (VAS; a scale from 0 to 100) was used to measure discomfort and pain.

Statistics

Data obtained from the VAS were subjected to statistical analysis (zero hypothesis) by two-sided Fisher exact test. A P value <0.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

Table 3 shows the results of patient interviews. There was a significant difference in pain perception between open and laparoscopic approaches. Eighty-four per cent of the patients in group 3 (TAPP) had no pain, compared with 62% and 68% in groups 1 and 2 (Shouldice and Lichtenstein, respectively). Twenty-two per cent and 24% in groups 1 and 2, respectively, described slight discomfort and pain, compared with 15% in group 3. Pain of medium intensity was described by 13% and 5% in groups 1 and 2, respectively, and 1% in group 3. Intense pain was described by 3% in groups 1 and 2 and by none of the patients in group 3. The VAS median value for Shouldice repair was 35 (range 10–75), for Lichtenstein repair it was 33 (range 10–73) and for TAPP the mean value was 15 (range 10–68). For VAS values of less than 20 (corresponding to minor discomfort) there was no difference between the three groups.

For VAS values above 20, results after Shouldice and Lichtenstein did not differ significantly. Comparison of both those techniques with TAPP showed the values for TAPP to be significantly lower (P<0.01), and this was more evident with rising levels of pain (Table 4).

In the majority of patients, pain correlated with physical strain (Table 5). Again, patients who had undergone the TAPP procedure had fewer complaints related to physical activity and tolerated relatively high levels of physical exertion. No patient, after laparoscopic repair, experienced pain after light physical exercise. Eight patients from both groups after Shouldice and Lichtenstein repair described pain under moderate physical stress, compared to one patient after TAPP.

Table 6 shows limitations in daily life, leisure activities and sports after hernia repair. Fifteen per cent and 13% of the patients after Shouldice and Lichtenstein repair, respectively, found themselves limited when performing physical activities, compared to 2.4% of the patients after TAPP. Two patients each from groups 1 and 2 were limited in social activities or were unable to go to work. After TAPP (group 3) none of the patients that experienced chronic pain found themselves thereby limited in daily life activities. Moderate limitations in leisure activities were more frequent after the Shouldice and Lichtenstein approaches than after TAPP.

There were no complaints related to the insertion of the prosthetic mesh in the Lichtenstein and TAPP methods. No-one complained about the feeling of a foreign body, stiffness or rigidity in the region of the mesh implant.

Discussion

Hernia repair is one of the most frequently performed surgeries. The implementation of the so-called tension-free techniques has considerably contributed to the fact that even large or recurrent hernias can be repaired in a very dependable way [3, 5, 12]. However, now that the problem of recurrence has been substantially resolved , chronic pain after surgery has been receiving more attention.

Several risk factors have been identified to play a crucial role in the development of chronic pain [9], but the long-term influence of the different approaches to the groin and the presence or absence of a prosthetic mesh on long-term complaints is not clear [25]. Current studies of postoperative pain after hernia repair are difficult to compare, due to, mostly, retrospective, non-randomized designs and relatively short follow-ups. Furthermore, there is no randomized trial that compares a laparoscopic technique simultaneously with the two major standardized and established representatives of open surgery, Shouldice and Lichtenstein repair, which would allow the estimation of the influence of the different techniques on the development of chronic pain.

Our study attempted to address two questions. First, the influence of the type of approach to the groin (open or laparoscopic), and, second, the principle of repair (non-mesh repair or tension free).

The laparoscopic approach to the groin is surely less traumatic than the open techniques. In the case of the TAPP technique, it involves only the incision of the peritoneum and the preparation of the hernial sac, without major trauma to the abdominal wall, thus minimizing the risk of possible nerve injury and concomitant scarring [20]. This was confirmed by our data, and we concurred with other studies where the laparoscopic techniques were shown to cause less pain postoperatively [20, 33–35]. However, the laparoscopic techniques are more technically complex and have a very long learning curve [36]. It is essential that this fact be borne in mind when one is comparing the results of the different techniques, and for explaining the heterogeneous outcome of studies that are comparing the laparoscopic procedure with the technically less demanding open techniques. Our data regarding the results after TAPP seem to be better than those described in other studies, but we started this trial after having performed approximately 300 TAPP interventions at our clinic.

The majority of studies that compare mesh repair with non-mesh repair with regard to postoperative pain, physical activity or early return to work and leisure activities show significantly better results for the tension-free techniques [3, 21, 26, 37]. However, it is important for one to notice that the difference between Shouldice and the open tension-free Lichtenstein technique is not as evident as that between Shouldice and laparoscopic repair [26, 33, 38]. Furthermore, there is a difference in postoperative discomfort and pain after the two tension free-techniques in favour for the laparoscopic technique, although not as evident as that between Shouldice and TAPP [20, 34, 39, 40]. This indicates that the approach to the groin, and not only the tension-free principle, is also a crucial factor for postoperative comfort in hernia repair.

The important question is whether this holds true in the long run. Especially in the case of large or recurrent hernias, the tension-free techniques are an indispensable part of the surgeon’s armamentarium of a reliable repair. However, there are some uncertainties about the long-term behaviour of the implanted meshes. The commonly used (and also used in this study) heavyweight polypropylene meshes provoke a chronic inflammatory response [41]. Although there is really no serious indication in the literature about possible malignant transformation, the behaviour of the prosthetic mesh as a foreign body, with all its implications such as shrinkage and scarring, might be a risk factor for the development of chronic pain itself [18].

Chronic discomfort and pain in up to 40% of the patients after hernia surgery reflects serious surgical reality [4, 33]. The most common chronic pain syndrome correlates with physical stress and can be reproduced readily with manoeuvres that typically provoke abdominal-wall pain. There is some evidence that the reason for those complaints lies partly in the region of the medial inguinal ligament, where sutures involve pubic periostal structures, and the physiological tensing of this ligament then leads to pain [14]. The remarkable finding in our study was that, more than 4 years after surgery, both character and intensity of pain after the open techniques were similar. With regard to the discussion about the potential disadvantage that results from the implantation of a relatively rigid prosthetic mesh, and possible cicatrization and shrinking due to chronic inflammation, one may have expected similar complaints after both tension-free techniques, independently of whether the mesh was implanted by an anterior or posterior approach. This supports the hypothesis that the surgical trauma to the groin plays a crucial role in the development of chronic pain.

Conclusion

The incidence of postoperative pain after hernia repair differed with the type of surgical approach. The technically demanding laparoscopic TAPP repair resulted in a significantly lower frequency of postoperative pain than did the open Shouldice and tension-free Lichtenstein procedures. The presence of a prosthetic mesh was not the source of any complaints during the approximately 4 years of follow-up.

References

Amid PK, Shulman AG, Lichtenstein IL (1996) Open “tension-free” repair of inguinal hernias: the Lichtenstein technique. Eur J Surg 162:447–453

Bittner R, Leibl B, Kraft K, Daubler P, Schwarz J (1996) Laparoscopic hernioplasty (TAPP)—complications and recurrences in 900 operations. Zentralbl Chir 121:313–319

Collaboration EH (2000) Laparoscopic compared with open methods of groin hernia repair: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br J Surg 87:860–867

Bay-Nielsen M, Perkins FM, Kehlet H (2001) Pain and functional impairment 1 year after inguinal herniorrhaphy: a nationwide questionnaire study. Ann Surg 233:1–7

Hay JM, Boudet MJ, Fingerhut A, Poucher J, Hennet H, Habib E, Veyrieres M, Flamant Y (1995) Shouldice inguinal hernia repair in the male adult: the gold standard? A multicenter controlled trial in 1578 patients. Ann Surg 222:719–727

Liem MS, van der GY, van Steensel CJ, Boelhouwer RU, Clevers GJ, Meijer WS, Stassen LP, Vente JP, Weidema WF, Schrijvers AJ, van Vroonhoven TJ (1997) Comparison of conventional anterior surgery and laparoscopic surgery for inguinal-hernia repair. N Engl J Med 336:1541–1547

Schmedt CG, Leibl BJ, Bittner R (2002) Endoscopic inguinal hernia repair in comparison with Shouldice and Lichtenstein repair. A systematic review of randomized trials. Dig Surg 19:511–517

Tons C, Kupczyk-Joeris D, Pleye J, Rotzscher VM, Schumpelick V (1990) Cremaster resection in Shouldice repair. A prospective controlled bicenter study. Chirurgie 61:109–111

Amid PK (2002) A 1-stage surgical treatment for postherniorrhaphy neuropathic pain: triple neurectomy and proximal end implantation without mobilization of the cord. Arch Surg 137:100–104

Arlt G, Schumpelick V (2002) The Shouldice repair for inguinal hernia—technique and results. Zentralbl Chir 127:565–569

Broin EO, Horner C, Mealy K, Kerin MJ, Gillen P, O’Brien M, Tanner WA (1995) Meralgia paraesthetica following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. An anatomical analysis. Surg Endosc 9:76–78

Callesen T, Bech K, Kehlet H (1999) Prospective study of chronic pain after groin hernia repair. Br J Surg 86:1528–1531

Courtney CA, Duffy K, Serpell MG, O’Dwyer PJ (2002) Outcome of patients with severe chronic pain following repair of groin hernia. Br J Surg 89:1310–1314

Cunningham J, Temple WJ, Mitchell P, Nixon JA, Preshaw RM, Hagen NA (1996) Cooperative hernia study. Pain in the postrepair patient. Ann Surg 224:598–602

Filipi CJ, Gaston-Johansson F, McBride PJ, Murayama K, Gerhardt J, Cornet DA, Lund RJ, Hirai D, Graham R, Patil K, Fitzgibbons R Jr, Gaines RD (1996) An assessment of pain and return to normal activity. Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy vs open tension-free Lichtenstein repair. Surg Endosc 10:983–986

Fingerhut A, Millat B, Bataille N, Yachouchi E, Dziri C, Boudet MJ, Paul A (2001) Laparoscopic hernia repair in 2000. Update of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) Consensus Conference in Madrid, June 1994. Surg Endosc 15:1061–1065

Haapaniemi S, Nilsson E (2002) Recurrence and pain three years after groin hernia repair. Validation of postal questionnaire and selective physical examination as a method of follow-up. Eur J Surg 168:22–28

Heise CP, Starling JR (1998) Mesh inguinodynia: a new clinical syndrome after inguinal herniorrhaphy? J Am Coll Surg 187:514–518

Junge K, Peiper C, Rosch R, Lynen P, Schumpelick V (2002) Effect of tension induced by Shouldice repair on postoperative course and long-term outcome. Eur J Surg 168:329–333

Kumar S, Wilson RG, Nixon SJ, Macintyre IM (2002) Chronic pain after laparoscopic and open mesh repair of groin hernia. Br J Surg 89:1476–1479

Leibl BJ, Kraft B, Redecke JD, Schmedt CG, Ulrich M, Kraft K, Bittner R (2002) Are postoperative complaints and complications influenced by different techniques in fashioning and fixing the mesh in transperitoneal laparoscopic hernioplasty? Results of a prospective randomized trial. World J Surg 26:1481–1484

Schrenk P, Woisetschlager R, Rieger R, Wayand W (1996) Prospective randomized trial comparing postoperative pain and return to physical activity after transabdominal preperitoneal, total preperitoneal or Shouldice technique for inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 83:1563–1566

Tons C, Klinge U, Kupczyk-Joeris D, Rotzscher VM, Schumpelick V (1991) Controlled study of cremaster resection in Shouldice repair of primary inguinal hernia. Zentralbl Chir 116:737–743

Wright DM, Kennedy A, Baxter JN, Fullarton GM, Fife LM, Sunderland GT, O’Dwyer PJ (1996) Early outcome after open versus extraperitoneal endoscopic tension-free hernioplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Surgery 119:552–557

Bower S, Moore BB, Weiss SM (1996) Neuralgia after inguinal hernia repair. Am Surg 62:664–667

Fleming WR, Elliott TB, Jones RM, Hardy KJ (2001) Randomized clinical trial comparing totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair with the Shouldice technique. Br J Surg 88:1183–1188

Koninger JS, Oster M, Butters M (1998) Management of inguinal hernia—a comparison of current methods. Chirurgie 69:1340–1344

Tschudi J, Wagner M, Klaiber C, Brugger J, Frei E, Krahenbuhl L, Inderbitzi R, Husler J, Hsu SS (1996) Controlled multicenter trial of laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal hernioplasty vs Shouldice herniorrhaphy. Early results. Surg Endosc 10:845–847

Wellwood J, Sculpher MJ, Stoker D, Nicholls GJ, Geddes C, Whitehead A, Singh R, Spiegelhalter D (1998) Randomised controlled trial of laparoscopic versus open mesh repair for inguinal hernia: outcome and cost. Br Med J 317:103–110

Schumpelick V, Treutner KH, Arlt G (1994) Inguinal hernia repair in adults. Lancet 344:375–379

Amid K (2003) The Lichtenstein repair in 2002: an overview of causes of recurrence after Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty. Hernia 7:13–16

Bittner R, Schmedt CG, Schwarz J, Kraft K, Leibl BJ (2002) Laparoscopic transperitoneal procedure for routine repair of groin hernia. Br J Surg 89:1062–1066

The MRC Laparoscopic Groin Hernia Trial Group (1999) Laparoscopic versus open repair of groin hernia: a randomised comparison. Lancet 354:185–190

Lal P, Kajla RK, Chander J, Saha R, Ramteke VK (2003) Randomized controlled study of laparoscopic total extraperitoneal versus open lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair. Surg Endosc 17:850–856

Leibl BJ, Daubler P, Schmedt CG, Kraft K, Bittner R (2000) Long-term results of a randomized clinical trial between laparoscopic hernioplasty and Shouldice repair. Br J Surg 87:780–783

Wright D, Paterson C, Scott N, Hair A, O’Dwyer PJ (2002) Five-year follow-up of patients undergoing laparoscopic or open groin hernia repair: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 235:333–337

Zieren J, Zieren HU, Jacobi CA, Wenger FA, Muller JM (1998) Prospective randomized study comparing laparoscopic and open tension-free inguinal hernia repair with Shouldice’s operation. Am J Surg 175:330–333

Nordin P, Bartelmess P, Jansson C, Svensson C, Edlund G (2002) Randomized trial of Lichtenstein versus Shouldice hernia repair in general surgical practice. Br J Surg 89:45–49

Juul P, Christensen K (1999) Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 86:316–319

Bringman S, Ramel S, Heikkinen TJ, Englund T, Westman B, Anderberg B (2003) Tension-free inguinal hernia repair: TEP versus mesh-plug versus Lichtenstein: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 237:142–147

Rosch R, Junge K, Schachtrupp A, Klinge U, Klosterhalfen B, Schumpelick V (2003) Mesh implants in hernia repair. Inflammatory cell response in a rat model. Eur Surg Res 35:161–166

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Köninger, J., Redecke, J. & Butters, M. Chronic pain after hernia repair: a randomized trial comparing Shouldice, Lichtenstein and TAPP. Langenbecks Arch Surg 389, 361–365 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-004-0496-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-004-0496-5