Abstract

Quality of life (QoL) is a well-established outcome measure. In contrast to adult obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), little is known about the effects of treatment on QoL in children with OCD. This study aimed to assess QoL after cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in children and adolescents with OCD compared with the general population and to explore factors associated with potential changes in QoL after treatment. QoL was assessed in 135 children and adolescents (ages 7–17; mean 13 [SD 2.7] years; 48.1 % female) before and after 14 CBT sessions, using self-report and a caregivers proxy report of the Questionnaire for Measuring Health-related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents (KINDL-R). QoL was compared with an age- and gender-matched sample from the general population. Before treatment, QoL was markedly lower in children with OCD compared with the general population. QoL improved significantly in CBT responders (mean score change 7.4), to the same range as QoL in the general population. Non-responders reported no QoL changes after treatment, except for one patient. Comorbidity, family accommodation and psychosocial functioning were not associated with changes in QoL after treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first study of the changes in QoL after treatment of paediatric OCD. The assessment of QoL beyond symptoms and function in children with OCD has been shown to be reliable and informative. The results of this study support the application of QoL assessment as an additional measure of treatment outcome in children and adolescents with OCD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is reported with a prevalence of 0.5–3 % in children and adolescents [1–3]. This disorder has a chronic course in 40–75 % of cases [4–6]. The majority of children with OCD fulfil criteria for one or more other psychiatric diagnoses [7, 8]. Depression, anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and tic disorder are frequent comorbidities in paediatric OCD. In addition, elevated levels of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are reported in OCD in adults [9–11] as well as in children and adolescents [12]. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention (E/RP) is well documented and recommended as first-line treatment for paediatric OCD in international guidelines [13–16].

The assessment of quality of life (QoL) is established as an important outcome factor independent of symptom level, because pathology does not have a simple linear relationship with well-being [17]. QoL is defined as subjective well-being on several domains of life [18]. The European Agency for the evaluation of medicinal products and the U.S. Department of health and human service food and drug administration support the use of patient-rated outcomes, including QoL measures, in clinical trials and have published guidance on the development of reliable measures [19, 20]. In contrast to adult OCD, little is known about QoL of children and adolescents with OCD and nothing at all about the relationship between treatment of OCD and QoL in young people.

In adults, changes in QoL seem to be associated with OCD symptom severity [21, 22] and with the presence of comorbid conditions, particularly depression. To date, four review articles on QoL in adults with OCD have been published [23–26], all of which concluded that QoL was markedly lower in patients with OCD compared with the general population. Macy and colleagues [24] underlined the importance of QoL assessment in both clinical and research settings to examine disease burden, to monitor treatment effectiveness, to determine the extent of recovery from OCD and to take these factors into account when developing treatment plans.

A variety of studies have evaluated QoL changes after different treatment options. The common feature of all studies is that they have focused on adults only. A few studies evaluated QoL after a CBT intervention. For example, Diefenbach and colleagues [27] observed significant improvement in QoL among adults with OCD after CBT. Changes in OCD symptoms and QoL were highly related, although there was a subset of participants whose symptoms improved without corresponding improvement in QoL.

Other studies have explored the relationship of more complex treatment conditions with QoL including inpatient treatment, medication and behavioural interventions, or combinations of these conditions. Moritz and colleagues [28] explored changes in QoL after treatment in adults with OCD, and the association between QoL changes and symptom-related outcomes. Overall, QoL improved significantly in therapy responders relative to non-responders. Hertenstein and colleagues [29] investigated QoL before and after treatment in an inpatient setting followed by outpatient treatment. At baseline, participants had lower QoL compared with the general population. QoL improved significantly at 12-month follow-up but remained below the values in the general population. Hollander and colleagues [22] found evidence that long-term pharmacological treatment of OCD improved QoL and that symptom relapse was associated with deterioration in QoL. Tenney and colleagues [30] reported improved QoL following pharmacological interventions. Interestingly, treatment responders, defined by a 35 % reduction in the Y-BOCS score, did not differ in their improvement in QoL, suggesting that QoL improvement was not associated with symptom reduction.

The findings related to QoL from adult OCD research cannot be generalized to children, who experience continuous development [31] and different perceptions of subjective well-being compared with adults [32]. In addition, the evidence from one informant does not represent a sufficiently complete picture in paediatric QoL studies because child and parent reports have shown low agreement [33, 34]. Both perspectives are important because they are not expected to be identical, but rather that both are “part of the social reality we call child well-being” [35]. Therefore, both perspectives need to be considered to obtain reliable outcome information. Only a few studies have assessed QoL in children and adolescents with OCD. One study [36] evaluated baseline characteristics of children with OCD at a mean age of 12 years and their predictive value for QoL in young adulthood after an average of 9 years of follow-up. QoL was assessed at follow-up only. Remitters demonstrated better QoL than non-remitters. QoL in early adulthood correlated strongly with the severity of residual OCD symptoms but not with OCD symptom severity in childhood. Another study of long-term outcomes of children and adolescents with OCD [4] reported mildly to moderately affected QoL assessed at follow-up when the mean age of the participants was 18.6 years. At this time, 61 % reported very much or much improvement in OCD symptoms; QoL was not assessed at baseline. Lack and colleagues [37] found significantly lower QoL scores in 62 children and adolescents with OCD than in healthy controls assessed as part of the baseline before treatment. QoL was only moderately associated with OCD symptom severity, as reported by parents. Therefore, the authors suggested that OCD symptom severity and QoL are two related but distinct constructs. In addition, the presence of comorbid externalizing and internalizing symptoms was a strong predictor of lower QoL scores. A previous study from our group [38] reported on QoL and baseline characteristics before treatment. This study confirmed the findings of Lack and colleagues in a larger sample size showing considerably impaired QoL in children with OCD. Children with OCD and comorbidity had the lowest QoL compared with those with OCD only. Lack and colleagues stated in 2009 that evidence from studies of adults with OCD suggests that both CBT and pharmacotherapy are associated with improved QoL following treatment, but this has yet to be studied in youth. The most recent review on QoL in adults with OCD [26] stated : “…little is known about the impact of OCD on QoL in paediatric patients. As there is a substantial prevalence of OCD in childhood and adolescence due to its early age of onset, there is an obvious need for further exploration of QoL in these populations; however, this is currently lacking.”

In this paper, we report on the relationship between a treatment intervention with CBT and QoL in children and adolescents with OCD, assessing prospectively QoL before and after treatment.

Aims

The aims of the present study were: (1) to assess changes of QoL after treatment with CBT in children and adolescents with OCD reported both by children and their caregivers, compared with QoL rating in an age- and gender-matched sample of student and parent reports from the general population, and (2) to assess whether the treatment response, comorbidity, psychosocial functioning or family accommodation are associated with QOL changes after controlling for gender, age and socio-economic status (SES).

Methods

Participants

Sample description

The present QoL study is a substudy of a multicentre treatment research project, the Nordic Long-term OCD Treatment Study (NordLOTS), in which 269 children and adolescents, aged 7–17 years, were treated for OCD with CBT between September 2008 and June 2012. The NordLOTS trial has been described in detail elsewhere [39–41]. We use the term “children” to denote children and adolescents in this paper. The present QoL study was initiated later than the NordLOTS and at different time points in the three participating countries because of differences in the availability and approval of the national translations of the QoL questionnaire used. Of 155 patients eligible for participation in the study, 22 refused to participate or did not complete the QoL instrument Questionnaire for Measuring Health-related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents, revised version (KINDL-R). Each child and one of his or her caregivers completed the QoL questionnaire at baseline, giving 135 completed forms from either a child and/or one caregiver. Completed QoL assessments after treatment were available for 106 children and parents (Fig. 1). ASD was an exclusion criterion in the main treatment study, but nine individuals with Asperger’s syndrome/high-functioning autism (HFA) were included in a substudy at one site (Trondheim). Complete QoL assessment was available for eight of these nine patients. Details are described elsewhere [38].

Treatment

Treatment comprised 14 sessions of weekly individual CBT with E/RP based on the study protocol of March and Mulle in collaboration with Foa and Kozak [42]. The treatment was modified to include more extensive family participation based on the work of Piacentini and colleagues [43] and adapted to fit Nordic cultural conditions. Parents were encouraged to participate actively during the entire course of their child’s treatment and both the child and the parent to jointly attend sessions 1–3, 7, 11 and 14. During these sessions, information was provided about treatment rationale and goals, and the parents’ role in the treatment process, and ideas about particular OCD problem areas for the child were addressed. In the remaining sessions, 45 min of individual CBT was offered to the child, followed by an additional 30 min for a parents’ session (with or without the child). The purpose of the latter was to address issues such as family accommodation, family support, problem solving and questions parents might have. The focus of the treatment was the gradual exposure to threatening situations based on a detailed symptom hierarchy, including homework exposure exercises. If appropriate, parents were asked to support and closely monitor homework assignments. Towards the end of the therapy, the emphasis shifted to generalizing skills and relapse prevention.

Treatment response

A clinical response was defined as a Children’s Y-BOCS (CY-BOCS) total score of ≤15, assessed by independent evaluators as the primary outcome measure and a 30 % reduction in the CY-BOCS score as a secondary outcome measure. Among the 106 children with complete QoL data, 71 (67 %) were treatment responders and 35 (33 %) non-responders.

Age, gender, ethnicity and SES

At baseline, the mean age of the participants was 13 years (SD 2.7 years, range 7–17). The gender distribution was even, with 65 girls (48.1 %). Thus, the QoL study sample was representative of the NordLOTS, in which the mean age was 12.8 (SD 2.7) years, whereas the gender distribution diverged slightly with more girls represented (51.3 %). If compared without the nine male participants from the ASD substudy, the gender distribution was equal in both samples (51.3 vs. 51.6 % girls in the QoL study). Ethnicity was primarily Scandinavian: 97 % of the participants had one or both parents of Scandinavian origin. SES was calculated using the highest educational level of either the mother or father (whichever was highest) and assessed as suggested by Hollingshead [44]; the scores ranged from 1 to 7 (7 = university education). The educational level of parents was generally high (M = 5.30; SD 1.39). The SES in the QoL study participants did not differ significantly from that of the participants in the main NordLOTS study (t(270) = 0.92; p = 0.357; M = 5.14, SD = 1.47).

Comorbidity

Comorbidity at baseline was common, especially neuropsychiatric conditions, other anxiety disorders and, to a lesser degree, depression. Only 69 patients (52.3 %) had “pure” OCD without any other comorbidity (hereafter named “OCD only”). Eighteen patients (13.6 %) met the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 4th edition (DSM-IV) [45] criteria for ADHD and 37 (28 %) for tic disorder; 14 had both. Conduct disorders were diagnosed in six patients (4.5 %). Other anxiety disorders were diagnosed in 28 patients (21.2 %): two patients had separation anxiety, 16 specific phobia (12.1 %), eight social phobia (6.1 %), six generalized anxiety disorder (4.5 %) and two unspecified anxiety. Four patients had two and one patient had three additional anxiety disorders. Seven patients (5.3 %) had depression; six of these seven had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder and the other had unspecified depression. No other psychiatric comorbidity was diagnosed. The ASD group (n = 9) contributed heavily to the load of comorbidity: only one of the ASD patients had OCD only, seven had other neuropsychiatric conditions (three with tic disorder, two with ADHD and two with both tics and ADHD) and one patient had another anxiety disorder (specific phobia).

Attrition

Baseline assessment of QoL resulted in 135 completed forms from either children and/or one of their caregivers (133 child forms and 130 parent forms, including two cases where only the parents completed the questionnaire and five cases where only the children completed the questionnaire). This yielded response rates of 86 % for eligible children and 84 % for the parents. Post-treatment QoL assessment was available for 109 participants (70 %). In three cases with QoL assessment, post-treatment responder status was missing at the time of the data analysis. Attrition from missing QoL reports or responder status resulted in a response rate of 68 % (n = 106) of all invited participants (children and parents) who completed QoL assessments before and after treatment (see Fig. 1).

Comparison group

A large normative data sample comprising students from schools in Sør-Trøndelag county [46, 47], which represents a comparable geographical area as the study area with both urban and rural settlement, was used as a control group. Every child or adolescent with OCD was matched individually with a control from the general population sample (n = 1,821, aged 8–16 years). This sample was stratified according to gender and age, and controls were numbered consecutively in each stratum. Using computer-generated random numbers, we then allocated each patient to a control. The parents’ educational level did not differ significantly between patients (M = 5.19) and the allocated controls from the general population (M = 5.29) (t(118) = 0.51, p = 0.61, paired-samples t test). Details of the general population sample are described elsewhere [38].

Instruments

QoL

The KINDL-R [48] is a well-established QoL instrument used in several clinical and epidemiological studies. Swedish and Norwegian versions of the questionnaire were available, and the Danish translation was prepared and approved by the original authors. We used the self-report questionnaire for children and adolescents as well as the proxy version completed by one of the parents. The questionnaire comprises 24 items, whose scores are equally distributed into six subscales: physical well-being, emotional well-being, self-esteem, family, friends and school. Each item addresses the child’s experiences over the past week and is rated on a five-point scale (1 = never, 5 = always). The mean item scores are calculated for all subscales and for the total QoL scale, which is transformed to a 0–100 scale, with 100 indicating very high QoL. The instrument also provides a disorder-related subscale yielding information about the perception of the disorder burden. We modified the form by adding the sentence “Concerning your OCD …” for children, and “Concerning your child’s OCD …” for parents to the disorder-related questions to ensure we tracked the informants’ perception of OCD and not a concurrent somatic or other disorder. Psychometric testing of the KINDL-R revealed good scale utilization and scale fit as well as moderate internal consistency [49]. A Norwegian normative study also confirmed satisfactory internal consistency and test–retest reliability [47] and ceiling effects [46]. In a review of QoL measures in children and adolescents, Solans and colleagues [50] found that the KINDL-R is one of the few identified generic instruments for which acceptable sensitivity to change has been reported.

OCD diagnosis and comorbidity

The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL) [51] is a widely used semi-structured interview for diagnostic assessment of DSM-IV [45] psychiatric disorders and subsyndromal symptomatology in children and adolescents. The K-SADS-PL was used to confirm the diagnosis of OCD according to the DSM-IV and to evaluate comorbidity. The K-SADS-PL was administered by interviewing the parent(s) and the child. Approved translations of the revised version of the K-SADS-PL [52] used in the study were available for all three languages.

OCD symptom severity

Symptom severity was assessed with the CY-BOCS [53] including the Clinical Global Impression (CGI). The CY-BOCS is a semi-structured interview containing checklists of obsessions and compulsions. Scales assessing the severity of obsessions and compulsions separately (range 0–20) are added to a CY-BOCS total score (range 0–40). Finally, a global severity score (CGI) is assigned based on all information gathered during the interview. The checklists and the severity ratings were based on interviews with each child and each parent or adult informant. CGI is a widely used rating scale for clinicians to assess the global severity of illness with a score ranging from 0 (“no illness”) to 6 (“serious illness”). The CY-BOCS showed reasonable reliability and validity, high internal consistency (α = 0.90) and test–retest reliability for the total score (ICC = 0.79), and good inter-rater agreement (ICC = 0.84) for the total score [54, 55].

Family accommodation

The Family Accommodation Scale (FAS) [56] is a 12-item clinician-rated questionnaire, designed to assess the family’s accommodation to the child’s OCD symptoms. The FAS items measure the extent to which family members provide reassurance or objects needed for compulsions, decrease behavioural expectations of the child, modify family activities or routines and help the child avoid objects, places or experiences that cause distress. The FAS has demonstrated good psychometric properties including good internal consistency (α = 0.76–0.80) [56, 57] and positive correlations with measures of OCD symptom severity [58] and family discord [56].

Children’s Global Assessment Scale

The Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) is a rating scale for assessing children’s general level of psychosocial functioning and is used primarily by clinicians [59]. It is used widely as a measure of the overall severity of disturbance in children; for example, for treatment evaluation as well as an index of impairment in epidemiological studies. Scores range from 1 (most impaired) to 100 (healthiest). The CGAS has demonstrated adequate inter-rater and test–retest reliability [60, 61].

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS), version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

At baseline, 0–9.2 % of the parents’ reports had missing values for the first five of six KINDL-R subscales, and 10.8–13.1 % had missing values in the disorder subscale. The corresponding percentages of missing values in the children’s reports were 0–6.0 % for the first five subscales and 5.3–8.3 % for the disorder subscale. At the post-treatment assessment, 0–6.6 % of the parents’ reports had missing values for the first five subscales of the KINDL-R and 10.7–13.9 % had missing values for the disorder subscale. The corresponding percentages of missing values in the children’s reports were 0.8–7.3 % for the first five subscales and 10.6–12.2 % for the disorder subscale. Missing values were substituted with the mean according to the KINDL-R manual, which states that if more than two questions in a section of four were not answered, no subscale score nor a total QoL score is produced. Accordingly, the number of participants varied between subscales and QoL total scores.

In all other instruments, there were low percentages of missing values: 0 % (CY-BOCS) to 3.7 % (FAS). Missing values and attrition were in general low. Therefore, statistical calculations were conducted as complete case analyses.

Changes in the participants’ total QoL scores before (T1) and after treatment (T2) and level of QoL after treatment compared with QoL level in the general population were analysed by paired sample t tests. Linear regression analyses of the difference in QoL scores between T2 and T1 as the dependent variable, dichotomized as responders and non-responders to treatment, were used to estimate the changes in QoL after treatment. All linear regression analyses were adjusted for gender, age and SES as potential confounders. The Pearson Chi-squared test was used to analyse differences in QoL total score between T1 and T2 in participants who were not classified as responders to treatment.

Results

QoL in children with OCD before and after treatment

QoL as reported by children with OCD and their caregivers improved markedly after treatment (Table 1). The changes in QoL total scores and all subscale scores except the friends and school subscale in the children’s report were significant (see Table 1).

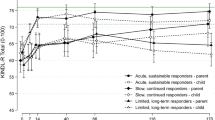

QoL changes in responders versus non-responders to treatment

QoL total score changed significantly in the responders (mean change 7.4 for children’s reports and 9.2 for parents’ reports) but changed only slightly in non-responders (mean change 0.23 for children’s and 1.2 for parents’ reports). Being a responder was associated with QoL improvement from T1 to T2 in both the children’s reports (β = 0.30; p = 0.002) and parents’ reports (β = 0.32; p = 0.001) (Fig. 2). There was no significant effect of potential confounders (gender, age and SES) on parents’ or children’s reports.

In a subsequent analysis, we identified six children (and five parents) who reported clinically important QoL improvement, defined as a difference in QoL total score between baseline (T1) and post-treatment assessment (T2) of >9 without being classified as responders to treatment (CY-BOCS total score <16). The difference was significant: χ 2(1) = 10.31; p = 0.002 in children’s reports and χ 2(1) = 5.35; p = 0.027 in parents’ reports. Further inspection of the data showed that the CY-BOCS scores decreased markedly from T1 to T2 in these participants, although not to the extent that they met the criteria for a clinical response (i.e., CY-BOCS <16). One participant reported QoL improvement without clinical improvement (no change in CY-BOCS score).

Comorbidity and changes in QoL after treatment

The presence of comorbidity, defined as OCD only versus OCD with any comorbidity as assessed at the baseline, was not associated with changes in QoL. The QoL change between T1 and T2 did not differ significantly in children with comorbidity compared with those without comorbidity as indicated in both the children’s reports (β = 0.001, p = 0.989) and parents’ reports (β = 0.018, p = 0.854).

This was also the case when the study population was dichotomized as responders and non-responders: children’s report responders β = –0.039 (p = 0.751) and non-responders β = 0.180 (p = 0.300); and parents’ report responders β = –0.023 (p = 0.853) and non-responders β = 0.149 (p = 0.424).

Family accommodation and changes in QoL after treatment

Family accommodation, defined by the FAS score at the baseline, was not associated with changes in QoL after treatment for the total group: children’s reports β = 0.102 (p = 0.301) and parents’ reports β = 0.142 (p = 0.158). When dichotomized into responders and non-responders to treatment and after controlling for confounders (gender, age and SES), the baseline FAS score was not associated with changes in QoL total scores in the children’s reports (non-responders: β = 0.315, p = 0.098; responders β = 0.073, p = 0.594) and in the parents’ reports (non-responders: β = 0.294, p = 0.115; responders β = 0.132, p = 0.274).

Psychosocial functioning and changes in QoL after treatment

Psychosocial functioning, defined by the CGAS score at baseline, was not associated with changes in QoL after treatment: children’s reports β = –0.004 (p = 0.965) and parents’ reports β = 0.017 (p = 0.871). When dichotomized into responders and non-responders, the CGAS score at baseline was not associated with QoL changes.

QoL after treatment compared with QoL levels in the general population

In the analysis of responders and non-responders together, the post-treatment QoL total score reported by children did not differ significantly from that in the general population: QoL total score mean difference −2.25 (p = 0.178). However, parents’ rating of QoL total score differed between responders and non-responders: mean difference –7.30 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). When dichotomized into responders and non-responders, the QoL scores for non-responders were significantly different from those of the matched cases from the general population in both the children’s and parents’ rating: QoL total score mean difference −10.78 (p < 0.001) for the children’s reports and −18.36 (p < 0.001) for the parent reports. By contrast, after treatment, the responders achieved the same QoL as reported in the matched cases in the general population: QoL total score mean difference 1.76 (p = 0.347) for the children’s reports and 2.17 (p = 0.210) for the parents’ reports (see Fig. 2).

Discussion

QoL as reported by both children with OCD and their caregivers improved substantially after treatment. QoL total scores increased significantly in the responders to treatment, to such an extent that they were similar to that of the matched controls in the general population. The presence of comorbidity, degree of family accommodation and level of psychosocial functioning were not associated with changes in QoL after treatment.

QoL levels after treatment corresponding to QoL in the general population

In our sample, the baseline QoL was markedly lower in children with OCD compared with the general population. This is consistent with studies of OCD in adults and the two published studies of baseline or population data for paediatric OCD patients [37, 62]. We found that, after treatment, the QoL ratings in the responders were in the same range as in the general population, whereas non-responders to treatment exhibited almost no change in QoL except for one patient. These findings suggest that the CBT treatment intervention was highly effective in reducing symptoms in responders and in improving QoL to the level observed in the general population. Similarly, in the previously mentioned follow-up study of Palermo and colleagues [36], remitters to treatment showed no impaired QoL in adulthood, and non-remitters had mild QoL impairment only. However, these studies cannot be compared directly. The therapeutic intervention in the study by Palermo and colleagues included medications and/or behavioural therapy throughout the study interval, but some of the participants continued to receive active psychiatric treatment, including medication in 60 % of participants, when QoL was assessed at a mean age of 21 years. In addition, data from the baseline assessment and for a general population control were not available in the study by Palermo and colleagues, and long-term follow-up data are not yet available for our study.

Our findings of QoL improvement to normal levels after treatment contradict the findings from studies in adults. For example, Huppert and colleagues [63] found that QoL scores in individuals in remission tended to be between those of healthy controls and individuals with current OCD, and to not differ significantly from either group. Moritz and colleagues [28] found significantly improved QoL in therapy responders relative to non-responders but that compromised QoL persisted in most patients over time. OCD severity correlated only modestly with QoL suggesting that QoL improvement after treatment reflected several factors that influence QoL and not just improved OCD symptoms. In Hertenstein’s study [29], QoL improved significantly after 12 months of intensive state-of-the-art treatment, but the QoL indices remained considerably lower than the population norm values. By contrast, our results showed that appropriate treatment of children and adolescents who were treatment responders improved QoL to levels in the normal population. One explanation might be that treatment in children has a more profound effect on QoL because it is likely that children have a shorter course of the disorder than do adults. In addition, in paediatric patients, treatment may increase the number of patients who experience complete remission of symptoms, whereas samples of adult patients may include a higher frequency of chronic patients. However, Hertenstein assessed QoL at baseline and at follow-up 12 months after the inpatient treatment, which included continuing outpatient treatment, whereas QoL in our sample was assessed after 14 weeks of treatment intervention. Thus, it is not clear whether the QoL scores in our study will be maintained in the normal range 1 year after the therapeutic intervention. Our study includes a follow-up over 3 years after treatment to explore whether the treatment gains in terms of symptom reduction and QoL improvements will be stable over time.

Children’s self-reports versus parents proxy reports

Children in general reported their QoL to be better than their caregivers did. In a review on parent–child agreement in QoL measurement [34], parents of children in a non-clinical sample tended to report higher child QoL scores than the children themselves, while parents of children with health conditions tended to underestimate their children’s QoL. However, Sattoe and colleagues [33] found reasonable agreement (i.e., in 43–51 % of cases) and most disagreement tended to be minor, suggesting that the proxy problem may be smaller than presented in the literature and its extent may differ between populations. In addition, one must bear in mind that not only children’s reports, but also the reports of parents can be biased [64]. In any case, both children’s reports and parents’ proxy reports should be obtained in the assessment of QoL to cover both informants’ unique perspectives.

Treatment evaluation and QoL measurement

There is an ongoing discussion in the field about the standards for treatment evaluation in terms of the optimum definitions of treatment response, remission criteria, symptom reduction and the need to include other outcome parameters such as functional impairment and health-related QoL measurements [65, 66]. Tolin and colleagues [66] questioned the external validity of clinical trial results; i.e., whether the gains seen on standardized clinical measures correspond to clinically meaningful changes in real-world functioning. Lack and colleagues [37] strongly recommended QoL assessment in paediatric OCD patients as a relevant parameter for both assessment and treatment evaluation. According to the authors, “targeting symptoms only without attending to QoL may result in the confounding of assessment data as the patient may have reduced symptoms that do not translate into improved day-to-day functioning”.

In many studies, a treatment response is defined as a 25–35 % reduction from baseline in the Y-BOCS or CY-BOCS score [65, 66]. In the NordLOTS study, responders were defined by a CY-BOCS score of <16. This definition was based on the experience in the Paediatric OCD Treatment Study, in which the same value was used to define clinically relevant OCD symptoms [67]. Another reason for the comparably high cut-off score was the fact that non-responders were later randomized to receive either CBT or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). To avoid ethical problems treating children with only mild symptoms with medication, the criterion of a CY-BOCS score of <16 was used to indicate response. As a secondary outcome measure, a 30 % reduction in the CY-BOCS score was added to ensure that the primary outcome measure of a CY-BOCS score <16 did not inflate the number of responders.

In the abovementioned study by Palermo and colleagues [36], remission was used to define a treatment response as: remitters Y-BOCS score, <8; mild OCD, 8–15; moderate OCD, 16–23; and severe OCD, >23. Consequently, they reported a larger number of individuals without QoL impairment (57 %) than the number of remitters (42 %) and that non-remitters had only mild QoL impairment in adulthood. These results may suggest that QoL was not directly related to symptom level despite the strong correlation between QoL and severity of residual symptoms. However, if a definition of responders with a Y-BOCS score of <16 including the participants with only mild OCD is applied, the percentage of responders would increase to 80 %, which supports our finding that QoL impairment was closely related to symptom level in children with OCD.

In a study of adults treated with medication, Hollander and colleagues [22] found that improvements of QoL correlated closely with improvements in the Y-BOCS score. They suggested that an important step towards achieving a consensus for any given outcome based on the Y-BOCS criterion is to demonstrate that such a criterion distinguishes patients on the basis of a clinically meaningful assessment that varies as a function of the Y-BOCS score. When they defined a response as a ≥25 % improvement in the Y-BOCS total score relative to the baseline, the mean QoL scores for responders and non-responders were clearly distinguishable.

We also found a clear relationship between symptomatic improvement and QoL, suggesting that QoL assessed using the KINDL-R is sensitive to treatment outcomes. This supports the use of the CY-BOCS cut-off scores used in this study to define treatment outcomes. However, a small subsample comprising six individuals reported clinically important QoL improvement without being classified as responders to treatment. Five of these participants had a large reduction in their CY-BOCS score (>9), but this change was not to an extent that they met the criteria for a clinical response. Only one participant reported QoL improvement without clinical improvement. Thus, without QoL evaluation or additional outcome criteria, a treatment response in these individuals could have been overlooked.

Our results of a close relationship between symptom reduction and QoL improvement are consistent with the results of Diefenbach [27] and Hollander [22] in adults with OCD. However, other reports have suggested an independence between a symptom response and QoL improvement in adults [30, 68]. Again, the reason for our findings could be that treatment in children has a more profound effect on QoL because it is likely that children have a shorter course of the disorder than adults. Another explanation, related more to the methodology, is that the various QoL assessment instruments have different sensitivities in terms of their ability to detect changes.

Comorbidity and QoL

Both ADHD and Tourettes syndrome (TS) are associated with poor QoL in children and adolescents [69, 70] and comorbidity seems to contribute to QoL reduction. Several studies investigated QoL in children and adolescents with TS. Both OCD and ADHD were significant contributors to the poor QoL in TS [71–73]. Comorbid OCD appeared to exert a greater impact on self and relationship domains of QoL and the combination of both OCD and ADHD in children with TS led to more widespread problems [74]. In an attempt to disentangle the differential impact of comorbid OCD and ADHD, Eddy and colleagues [75] found that severity of OCD symptoms was negatively related to QoL in several domains, suggesting that comorbid OCD could have a more widespread negative impact on QoL, whereas ADHD symptoms appeared to have a negative impact on self and relationship domains only. However, in this study the presence of just one of these comorbid conditions did not lower QoL scores significantly. Surprisingly, in our study, the presence of comorbidity was not associated with changes in QoL after treatment in both the children’s and parents’ reports. At the baseline evaluation, children with comorbidity and especially neuropsychiatric conditions had lower QoL compared with those without comorbidity. Comorbid internalizing and externalizing problems were associated with reduced QoL, although the correlations were low to moderate [38]. One could presume that the presence of comorbidity may result in fewer effects on QoL after OCD treatment because the comorbid conditions will continue to have a negative influence on QoL after treatment. However, the presence of comorbidity at the baseline was not associated with QoL changes in responders or in non-responders to treatment. This may reflect an expanding effect of CBT to other symptoms and problems beyond the reduction in OCD symptoms. On the other hand, the marked treatment impact on QoL in responders might override the lack of improvement in the small group of non-responders. This is congruent with treatment outcome studies. In adult OCD, comorbidity does not seem to decrease the effectiveness of CBT for anxiety disorders [76, 77]. In children and adolescents comorbidity seems to affect CBT outcome differently. The presence of comorbid anxiety and tic disorders did not negatively affect CBT response, but other comorbidities as ADHD, conduct disorders and depression did [78]. In our sample, tic disorders (28 %) and anxiety disorders (21 %) were the most frequent diagnosed comorbidity groups. Also in the study of Palermo and colleagues [36], childhood comorbid conditions such as tic disorders, ADHD, depression and other anxiety disorders had no significant value for predicting QoL in early adulthood.

In adults with OCD, the additive impact of comorbid depression on QoL is well documented [22, 24]. In Hertenstein’s study [29], QoL improvement after treatment was predicted by improvements in depressive symptoms. Moritz and colleagues [28] found the strongest correlations with QoL for depression severity and number of OCD symptoms. Hupert and colleagues [63] found that participants with OCD and comorbid psychiatric diagnoses showed the poorest QoL and that comorbid depression accounted for much of the variance. In the study of Kugler and colleagues [79], depressive symptoms mediated the relationships between obsessive–compulsive symptom severity and emotional health, social functioning and general health QoL. In the only available study providing information about depressive symptoms in adolescents with OCD, Vivan Ade and colleagues [62] found a significant negative relationship between QoL and depressive symptoms as evaluated with the Beck Depressive Inventory. K-SADS-PL was used to confirm the diagnosis of OCD in the study, but no information about the relationship between QoL and depression above the diagnostic threshold was offered.

Severe depression with suicidal ideation was an exclusion criterion in the NordLOTS study. This could be one of the reasons why we had a low prevalence of depression in our sample. At the baseline assessment, only seven patients were diagnosed with depressive disorder. These patients and their parents reported tendencies to lower QoL compared with all other patients, but without reaching significance levels. Six of the seven patients with depression had one or more additional comorbidities. Thus, an analysis of the change in QoL in patients with comorbid depression during treatment would not allow any conclusion at all. The impact of comorbid depression on QoL may also reflect the total load of all comorbidities, which was not significant, as noted above.

Impact of family accommodation and psychosocial functioning on QoL

Family accommodation and psychosocial functioning at the baseline were not associated with changes in QoL after treatment in the children’s and in the parents’ reports. At the baseline evaluation, family accommodation was associated with low QoL, but the correlations were low to moderate [38]. Our findings may indicate that CBT was highly effective in most patients independent of the baseline psychosocial and family function. In the study of adults by Diefenbach and colleagues [27], more impaired family functioning was the only demographic or clinical characteristic to differentiate the subgroup of patients whose improvements in OCD symptoms corresponded with improvements in QoL. The authors considered that this subgroup may have received more treatment that specifically targeted family functioning because the patients had more family involvement in rituals. However, because of the lack of measures of family accommodation in rituals, this hypothesis could not be tested. In our study, considerable effort was put into family work by encouraging caregivers to actively participate during their child’s treatment. One interpretation of our results is that even non-responders had a non-specific benefit of the family component of the treatment.

Limitations

Because of the homogeneous socio-demographic factors and similarities in culture and language of the population in the Nordic countries, our sample was comprised of mostly relatively highly educated families of Caucasian origin. For example, the inability to understand one of the Nordic languages was an exclusion criterion. This represents a clear limitation to the generalization value for other populations. Another limitation is the lack of a treatment control group in our study. Although our results offer strong empirical support that QoL in children and adolescents with OCD is improved following CBT, conclusions about the causal relationship between CBT and QoL improvement cannot be drawn. A third limitation is the lack of follow-up data because QoL was assessed directly after the therapeutic intervention. There is no information available about the long-term impact of CBT on QoL in children with OCD. Thus, it is not clear whether the improved QoL scores will be maintained in this range or will deteriorate over time. A last concern is the use of a generic QoL instrument and not a disorder-specific QoL measure. Disorder-specific measures, designed to assess QoL in a certain diagnostic group may be more sensitive for QoL aspects which are particularly relevant for this group, while a generic instrument might underestimate those aspects. However, our aim was to compare QoL in children with OCD with QoL in the general population. Therefore, we had to use a generic instrument, allowing comparison between different populations. It could have been an advantage to add an OCD-specific QoL instrument, to cover aspects of QoL specifically related to OCD, for example involvement of parents in rituals, within the OCD group. One OCD-specific QoL instrument, Quality of Life in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (QoLOC) is developed for adults [80]. For paediatric patients a disorder-specific QoL instrument is available for TS [81], but to our knowledge still to develop for OCD.

Conclusion

Children and adolescents with OCD had significantly lower QoL before treatment compared with the general population of children and adolescents. Responders to treatment exhibited improved QoL to the level reported in the general population. Non-responders reported no QoL changes after treatment except in one patient. Our findings suggest that QoL assessment with the KINDL-R is valid, informative and sensitive to treatment outcomes in paediatric OCD patients and supports the use of the CY-BOCS cut-off scores used in the study to define treatment outcomes. The results of this study support the application of QoL assessment as an additional measure of treatment outcome in children and adolescents with OCD.

References

Heyman I, Fombonne E, Simmons H, Ford T, Meltzer H, Goodman R (2001) Prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the British nationwide survey of child mental health. Br J Psychiatry 179(4):324–329. doi:10.1192/bjp.179.4.324

Valleni-Basile LA, Garrison CZ, Jackson KL, Waller JL, McKeown RE, Addy CL, Cuffe SP (1994) Frequency of obsessive-compulsive disorder in a community sample of young adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33(6):782–791. doi:10.1097/00004583-199407000-00002

Verhulst FC, van der Ende J, Ferdinand RF, Kasius MC (1997) The prevalence of DSM-III-R diagnoses in a national sample of Dutch adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54(4):329–336

Micali N, Heyman I, Perez M, Hilton K, Nakatani E, Turner C, Mataix-Cols D (2010) Long-term outcomes of obsessive-compulsive disorder: follow-up of 142 children and adolescents. Br J Psychiatry 197(2):128–134. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075317

Skoog G, Skoog I (1999) A 40-year follow-up of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56(2):121–127

Stewart SE, Geller DA, Jenike M, Pauls D, Shaw D, Mullin B, Faraone SV (2004) Long-term outcome of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis and qualitative review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand 110(1):4–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00302.x

Hanna GL (1995) Demographic and clinical feature of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:19–27

Ivarsson T, Melin K, Wallin L (2008) Categorical and dimensional aspects of co-morbidity in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17(1):20–31. doi:10.1007/s00787-007-0626-z

Bejerot S, Nylander L, Lindstrom E (2001) Autistic traits in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nord J Psychiatry 55(3):169–176. doi:10.1080/08039480152036047

Cath DC, Ran N, Smit JH, van Balkom AJ, Comijs HC (2008) Symptom overlap between autism spectrum disorder, generalized social anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults: a preliminary case-controlled study. Psychopathology 41(2):101–110. doi:10.1159/000111555

LaSalle VH, Cromer KR, Nelson KN, Kazuba D, Justement L, Murphy DL (2004) Diagnostic interview assessed neuropsychiatric disorder comorbidity in 334 individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety 19(3):163–173. doi:10.1002/da.20009

Ivarsson T, Melin K (2008) Autism spectrum traits in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). J Anxiety Disord 22(6):969–978. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.10.003

AACAP (2012) Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51(1):98–113. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.019

Abramowitz JS, Whiteside SP, Deacon BJ (2005) The effectiveness of treatment for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy. Behavior Therapy 36:55–63. doi:10.1016/s0005-789428052980054-1

NICE (2005) Obsessive-compulsive disorder: core interventions in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. Clinical Guideline 31

Watson HJ, Rees CS (2008) Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled treatment trials for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49(5):489–498. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01875.x

Luhmann M, Hofmann W, Eid M, Lucas RE (2012) Subjective well-being and adaptation to life events: a meta-analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol 102(3):592–615. doi:10.1037/a0025948

Koot HM (2001) The study of quality of life: concepts and methods. In: Koot HM, Wallander JL (eds) Quality of Life in children and adolescent illness: Concepts, methods, and findings. Brunner-Routledge, East Essex, UK

EMEA (2004) Reflection paper on the regulatory guidance for the use of health-related quality of life (HRQL) measures in the evaluation of medicinal products European Medicines Agency London

FDA (2006) Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4:79. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-4-79

Eisen JL, Mancebo MA, Pinto A, Coles ME, Pagano ME, Stout R, Rasmussen SA (2006) Impact of obsessive-compulsive disorder on quality of life. Compr Psychiatry 47(4):270–275. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.11.006

Hollander E, Stein DJ, Fineberg NA, Marteau F, Legault M (2010) Quality of life outcomes in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: relationship to treatment response and symptom relapse. J Clin Psychiatry 71(6):784–792. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05911blu

Koran LM (2000) Quality of life in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 23(3):509–517

Macy AS, Theo JN, Kaufmann SC, Ghazzaoui RB, Pawlowski PA, Fakhry HI, Cassmassi BJ, IsHak WW (2013) Quality of life in obsessive compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr 18(1):21–33. doi:10.1017/S1092852912000697

Moritz S (2008) A review on quality of life and depression in obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr 13(9 Suppl 14):16–22

Subramaniam M, Soh P, Vaingankar JA, Picco L, Chong SA (2013) Quality of life in obsessive-compulsive disorder: impact of the disorder and of treatment. CNS drugs 27(5):367–383. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0056-z

Diefenbach GJ, Abramowitz JS, Norberg MM, Tolin DF (2007) Changes in quality of life following cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther 45(12):3060–3068. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.014

Moritz S, Rufer M, Fricke S, Karow A, Morfeld M, Jelinek L, Jacobsen D (2005) Quality of life in obsessive-compulsive disorder before and after treatment. Compr Psychiatry 46(6):453–459. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.04.002

Hertenstein E, Thiel N, Herbst N, Freyer T, Nissen C, Kulz AK, Voderholzer U (2013) Quality of life changes following inpatient and outpatient treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a study with 12 months follow-up. Ann Gen Psychiatry 12(1):4. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-12-4

Tenney NH, Denys DA, van Megen HJ, Glas G, Westenberg HG (2003) Effect of a pharmacological intervention on quality of life in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 18(1):29–33. doi:10.1097/01.yic.0000047752.19914.a8

Arbuckle R, Abetz-Webb L (2013) “Not just little adults”: qualitative methods to support the development of pediatric patient-reported outcomes. Patient 6(3):143–159. doi:10.1007/s40271-013-0022-3

Jozefiak T (2014) Can we trust in parents’ report about their childrens well-being? In: Holte A et. al. The psychology of child well-being. In: Asher Ben-Arieh FC, Ivar Frønes, Jill E. Korbin (ed) Handbook of child well-being. Theories, methods and policies in global perspective. Springer Netherlands, pp 555–631

Sattoe JN, van Staa A, Moll HA (2012) The proxy problem anatomized: child-parent disagreement in health related quality of life reports of chronically ill adolescents. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10:10. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-10-10

Upton P, Lawford J, Eiser C (2008) Parent-child agreement across child health-related quality of life instruments: a review of the literature. Qual Life Res 17(6):895–913. doi:10.1007/s11136-008-9350-5

Casas F in A. Holte MMB, Bekkhus M, Borge AIH, Bowes L, Casas F, Friborg O, Grinde B, Headey B, Jozefiak T, Lekhal R, Marks N, Muffels R, Nes RB, Røysamb E, Thimm J, Torgersen S, Trommsdorff G, Veenhoven R, Vittersø J, Waaktaar T, Wagner GG, Wang CE, Wold B, Zachrisson HD (2014) Psychology of child well-being In: Ben-Arieh A, Casas F, Frønes I, Korbin JE (eds) Handbook of child well-being: theories, metods and policies in global perspective. Springer, pp 555–632

Palermo SD, Bloch MH, Craiglow B, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Dombrowski PA, Panza K, Smith ME, Peterson BS, Leckman JF (2011) Predictors of early adulthood quality of life in children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46(4):291–297. doi:10.1007/s00127-010-0194-2

Lack CW, Storch EA, Keeley ML, Geffken GR, Ricketts ED, Murphy TK, Goodman WK (2009) Quality of life in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: base rates, parent-child agreement, and clinical correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 44(11):935–942. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0013-9

Weidle B, Ivarsson T, Thomsen PH, Jozefiak T (2014) Quality of life in children with OCD with and without comorbidity. Health Qual Life Outcomes 12:152. doi:10.1186/s12955-014-0152-x

Ivarsson T, Thomsen PH, Dahl K, Valderhaug R, Weidle B, Nissen JB, Englyst I, Christensen K, Torp NC, Melin K (2010) The rationale and some features of the Nordic Long-term OCD Treatment Study (NordLOTS) in childhood and adolescence. Child Youth Care Forum 39(2):91–99

Thomsen PH, Torp NC, Dahl K, Christensen K, Englyst I, Melin KH, Nissen JB, Hybel KA, Valderhaug R, Weidle B, Skarphedinsson G, von Bahr PL, Ivarsson T (2013) The Nordic long-term OCD treatment study (NordLOTS): rationale, design, and methods. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health 7(1):41. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-7-41

Torp NC, Dahl K, Skarphedinsson G, Thomsen PH, Valderhaug R, Weidle B, Melin K, Hybel K, Nissen JB, Lenhard F, Wentzel-Larsen T, Franklin ME, Ivarsson T (2014) Effectiveness of cognitive behavior treatment for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: acute outcomes from the nordic long-term OCD Treatment Study (NordLOTS). Behav Res Ther Forthcom. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2014.11.005

March JS, Mulle K, Foa E, Kozak MJ (2000) Treatment of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder cognitive behavior therapy treatment manual

Piacentini J, Langley A, Roblek T (2007) Cognitive behavioral treatment of childhood OCD: it’s only a false alarm : therapist guide. Oxford University Press, New York

Hollingshead AB (2011) Four factor index of social status Yale. J Sociol 8:21–52

APA (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Association, Washington. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423349

Jozefiak T, Larsson B, Wichstrom L (2009) Changes in quality of life among Norwegian school children: a six-month follow-up study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 7:7. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-7-7

Jozefiak T, Larsson B, Wichstrom L, Mattejat F, Ravens-Sieberer U (2008) Quality of life as reported by school children and their parents: a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 6:34. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-6-34

Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M (2000) KINDL-R. Questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life in children and adolescents—Revised version 2000. http://kindl.org/english/manual/

Bullinger M, Brutt AL, Erhart M, Ravens-Sieberer U, Group BS (2008) Psychometric properties of the KINDL-R questionnaire: results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17(Suppl 1):125–132. doi:10.1007/s00787-008-1014-z

Solans M, Pane S, Estrada MD, Serra-Sutton V, Berra S, Herdman M, Alonso J, Rajmil L (2008) Health-related quality of life measurement in children and adolescents: a systematic review of generic and disease-specific instruments. Value Health 11(4):742–764. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00293.x

Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N (1997) Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(7):980–988. doi:10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021

Axelson D, Birmaher B, Zelazny J, Kaufman J, Gill MK (2009) Kiddie-sads-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL) 2009 Working Draft. Department of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh. http://psychiatry.pitt.edu/research/tools-research/ksads-pl-2009-working-draft

Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS (1989) The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 46(11):1006–1011

Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, Cicchetti D, Leckman JF (1997) Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(6):844–852. doi:10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023

Storch EA, Murphy TK, Geffken GR, Soto O, Sajid M, Allen P, Roberti JW, Killiany EM, Goodman WK (2004) Psychometric evaluation of the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Psychiatry Res 129(1):91–98. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2004.06.009

Calvocoressi L, Mazure CM, Kasl SV, Skolnick J, Fisk D, Vegso SJ, Van Noppen BL, Price LH (1999) Family accommodation of obsessive-compulsive symptoms: Instrument development and assessment of family behavior. J Nerv Ment Dis 187(10):636–642. doi:10.1097/00005053-199910000-00008

Geffken GR, Storch EA, Duke DC, Monaco L, Lewin AB, Goodman WK (2006) Hope and coping in family members of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord 20(5):614–629. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.07.001

Storch EA, Geffken GR, Merlo LJ, Jacob ML, Murphy TK, Goodman WK, Larson MJ, Fernandez M, Grabill K (2007) Family accommodation in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clinic Child Adolesc Psychol 36(2):207–216

Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S (1983) A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry 40(11):1228–1231

Bird HR, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Ribera JC (1987) Further measures of the psychometric properties of the Children’s Global Assessment Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 44(9):821–824

Rey JM, Starling J, Wever C, Dossetor DR, Plapp JM (1995) Inter-rater reliability of global assessment of functioning in a clinical setting. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 36(5):787–792. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01329.x

Vivan Ade S, Rodrigues L, Wendt G, Bicca MG, Cordioli AV (2013) Quality of life in adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria 35(4):369–374. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1135

Huppert JD, Simpson HB, Nissenson KJ, Liebowitz MR, Foa EB (2009) Quality of life and functional impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a comparison of patients with and without comorbidity, patients in remission, and healthy controls. Depress Anxiety 26(1):39–45. doi:10.1002/da.20506

Davis E, Davies B, Waters E, Priest N (2008) The relationship between proxy reported health-related quality of life and parental distress: gender differences. Child Care Health Dev 34(6):830–837. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00866.x

Pallanti S, Hollander E, Bienstock C, Koran L, Leckman J, Marazziti D, Pato M, Stein D, Zohar J (2002) Treatment non-response in OCD: methodological issues and operational definitions. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 5(2):181–191. doi:10.1017/S1461145702002900

Tolin DF, Abramowitz JS, Diefenbach GJ (2005) Defining response in clinical trials for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a signal detection analysis of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. J Clin Psychiatry 66(12):1549–1557

Franklin ME, Sapyta J, Freeman JB, Khanna M, Compton S, Almirall D, Moore P, Choate-Summers M, Garcia A, Edson AL, Foa EB, March JS (2011) Cognitive behavior therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: the pediatric OCD treatment study II (POTS II) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 306(11):1224–1232. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1344

Bystritsky A, Liberman RP, Hwang S, Wallace CJ, Vapnik T, Maindment K, Saxena S (2001) Social functioning and quality of life comparisons between obsessive-compulsive and schizophrenic disorders. Depress Anxiety 14(4):214–218

Klassen AF, Miller A, Fine S (2004) Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents who have a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 114(5):e541–e547. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0844

Storch EA, Merlo LJ, Lack C, Milsom VA, Geffken GR, Goodman WK, Murphy TK (2007) Quality of life in youth with Tourette’s syndrome and chronic tic disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 36(2):217–227. doi:10.1080/15374410701279545

Bernard BA, Stebbins GT, Siegel S, Schultz TM, Hays C, Morrissey MJ, Leurgans S, Goetz CG (2009) Determinants of quality of life in children with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord 24(7):1070–1073. doi:10.1002/mds.22487

Cutler D, Murphy T, Gilmour J, Heyman I (2009) The quality of life of young people with Tourette syndrome. Child Care Health Dev 35(4):496–504. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00983.x

Eddy CM, Cavanna AE, Gulisano M, Agodi A, Barchitta M, Cali P, Robertson MM, Rizzo R (2011) Clinical correlates of quality of life in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord 26(4):735–738. doi:10.1002/mds.23434

Eddy CM, Rizzo R, Gulisano M, Agodi A, Barchitta M, Cali P, Robertson MM, Cavanna AE (2011) Quality of life in young people with Tourette syndrome: a controlled study. J Neurol 258(2):291–301. doi:10.1007/s00415-010-5754-6

Eddy CM, Cavanna AE, Gulisano M, Cali P, Robertson MM, Rizzo R (2012) The effects of comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder on quality of life in tourette syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 24(4):458–462. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11080181

Storch EA, Lewin AB, Farrell L, Aldea MA, Reid J, Geffken GR, Murphy TK (2010) Does cognitive-behavioral therapy response among adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder differ as a function of certain comorbidities? J Anxiety Disord 24(6):547–552. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.013

Lack CW, Yardley HL, Dalaya A (2013) Treatment of multiple co-morbid anxiety disorders. In: Storch EA, McKay D (eds) Handbook of treating variants and complications in anxiety disorders. Springer, New York

Storch EA, Merlo LJ, Larson MJ, Geffken GR, Lehmkuhl HD, Jacob ML, Murphy TK, Goodman WK (2008) Impact of comorbidity on cognitive-behavioral therapy response in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47(5):583–592. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816774b1

Kugler BB, Lewin AB, Phares V, Geffken GR, Murphy TK, Storch EA (2013) Quality of life in obsessive-compulsive disorder: the role of mediating variables. Psychiatry Res 206(1):43–49. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.10.006

Hauschildt M, Jelinek L, Randjbar S, Hottenrott B, Moritz S (2010) Generic and illness-specific quality of life in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Cogn Psychother 38(4):417–436. doi:10.1017/s1352465810000275

Cavanna AE, Luoni C, Selvini C, Blangiardo R, Eddy CM, Silvestri PR, Cali PV, Gagliardi E, Balottin U, Cardona F, Rizzo R, Termine C (2013) Disease-specific quality of life in young patients with tourette syndrome. Pediatr Neurol 48(2):111–114. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.10.006

Acknowledgments

This study was funded with support by the Norwegian Research Council and St. Olav’s Hospital, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Trondheim. We wish to thank all patients, parents, and the participating clinics for their contribution to the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. All parents gave written informed consent and the permission for their children to participate before inclusion in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weidle, B., Ivarsson, T., Thomsen, P.H. et al. Quality of life in children with OCD before and after treatment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24, 1061–1074 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0659-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0659-z