Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether patients’ skin color could exert an influence on the dentist’s decision-making for treatment, in four different cities in Brazil.

Material and methods

Lists of dentists were obtained and the sample selection was performed systematically. Two questionnaires were produced for the same clinical case, but the images were digitally manipulated to obtain a patient with a black and a white skin color. Dentists were free to choose treatment without any restrictions, including the financial aspects. A random sequence (white or black) was generated which was placed at random in sealed, opaque envelopes. Dentists were questioned about the decision on the treatment of a severely decayed tooth and an ill-adapted amalgam restoration.

Results

A total of 636 dentists agreed to participate in the study. After adjustments (multinomial logistic regression), it was observed that the black patient with a decayed tooth had a 50% lower risk of being referred for prosthetic treatment (p = 0.023) and a 99% higher risk of receiving a composite resin restoration, compared to the white patient (p = 0.027). No differences were observed regarding recommendation for tooth extraction (p = 0.657). In relation to an ill-adapted amalgam, the black patient had less risk of receiving a referral replacement with composite resin (0.09 95%CI [0.01–0.82]) and finishing and polishing (0.11 5%CI [0.01–0.99]) compared with the white patient.

Conclusion

Patient skin color influenced the dentist’s choice of treatment. In general, black patients receive referrals for cheaper, simpler procedures.

Clinical significance

Skin color played an important role in dentists’ treatment decisions. Professionals may contribute unconsciously to the propagation and replication of racial discrimination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Given the variability of techniques available in contemporary dentistry, the choice of treatment is an important aspect of dental practice and depends mainly on the referral and execution of professionals through the consent of patients. Several studies have reported that professional characteristics such as time since graduation and level of specialization can influence the choice of techniques or materials [1,2,3]. Although some studies have investigated the role that patient characteristics can play in the treatment decision by health professionals, information about how patient skin color may influence this decision is scant [4, 5]. Patients’ race and sex have influenced medical conduct concerning chest pain in patients with similar clinical signs, even after correction for confounders [5]. Similarly, Cabral et al. 2005 [4] investigate the influence of patient skin color on the choice of extraction of decayed teeth and observed a high referral for extraction in black individuals, compared with whites.

The recommendation of different treatments due to racial differences may be explained by several stereotypes, many of which are systematically reproduced, showing an essential interaction with inequality and socioeconomic barriers [6]. Skin color and income have been heavily correlated with both general and oral health conditions [7]. Black individuals have presented poorer health conditions, being frequently associated with higher prevalence of periodontal disease [8, 9], and dental caries [10]. Social deprivations in life’s course could lead to reduced access to oral healthcare and worse oral health habits, also influencing the quality of life of these individuals [10,11,12,13]. Diverse health disparities can be linked to racial discrimination, suggesting several levels of connection occurring in different ways, depending on the study population [6, 14, 15]. Although the measurement of socioeconomic status is able to quantify a large proportion—though not all—of the disparities related to ethnic discrepancies in health [16], the understanding of how health professionals participate in this process is extremely important because they are an active component in promoting and maintaining health and could influence this process.

Thus, professionals may also play—albeit unconsciously—important roles in the propagation and replication of discrimination [4, 5], especially since the majority of these professionals represent, in most cases, a socioeconomically favored minority. Therefore, the understanding of how this can occur in the clinical routine of professionals from different cities is of great relevance. Thus, the aim of the study was to investigate whether patients’ skin color could influence the dentist’s recommendation for treatment, in four different Brazilian cities.

Methods

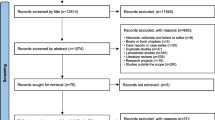

The present study was reported observing the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Checklist for randomized trials.

Trial design and interviews

The present randomized trial was performed in four different cities in Brazil, during the period between August 2016 and February 2017. Interviews were conducted with dentists in two cities in the southern region of the country (Pelotas and Caxias do Sul) and the other two in the northeast region (Aracaju and Fortaleza). The fieldwork team comprised four previously trained undergraduate dental students who performed the interviews, and two researchers that supervised the fieldwork. The interviews were performed in person with clinicians, using an electronic form employed using a Tablet (7″).

Participants

Dentists’ offices were previously identified through the ANVISA register (Brazilian health surveillance agency) in Pelotas, Caxias do Sul, and Fortaleza. In Aracaju, dentists were identified through the registration with the regional dental council (CRO-SE). Lists of dentists were obtained for all cities. Sample selection was performed systematically, selecting at random the first position in the list. Subsequent individuals were selected by calculating the sample interval, based on the number of dentists available in each city. Selected professionals were contacted in person and invited to participate in the study. All participants that agreed to participate in the study signed an informed consent form. Only dentists working as clinicians were approached. Those professionals who work exclusively in universities or who were no longer active in clinical practice were not included in the present study.

Intervention

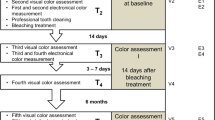

Two questionnaires were produced for the same clinical case, but with patients of different skin color (case A: white patient; and case B: black patient). An extraoral photograph of two individuals of different ethnicity was used to characterize the patients, and the same intraoral photo was used for both cases. The color of gingival and mucosal tissue was manipulated using Adobe Photoshop CS6™ (Adobe Corporation) software, obtaining an intraoral view of the black and white patients, respectively. Intra- and extraoral images of both patients are displayed in Fig. 1. Patient skin color was assigned at random. In addition, the patients’ socioeconomic status was not disclosed to avoid possible bias with the decision-making. Dentists were informed that they were free to choose treatments without financial restrictions.

Randomization

A random sequence (patient A or B) was generated using Excel™ (Microsoft Corporation) software, by an author who was not involved in the interviews and who deposited the sequence in numbered and sealed opaque envelopes. Randomization was performed in blocks of 20 envelopes. The envelopes were opened by the interviewers prior to applying the questionnaire (Fig. 2).

Outcomes

The following clinical case (Fig. 1a, white or Fig. 1b, black) was presented to dentists: “A 27-year-old male patient with normal oral health conditions went to Dr. (a) as he was unable to attend work because he had had ‘toothache for more than a week’. The patient gave Dr. (a) total freedom to decide the treatment. What would be your first treatment option?” The treatment options were (a) extraction, (b) endodontic treatment followed by prosthetic rehabilitation, and (c) endodontic treatment followed by direct composite resin restoration. After the first question had been answered, the second question was presented: “In the same consultation, the following amalgam restoration (Fig. 1) was identified in a first upper premolar. Similarly, the patient gives you freedom to make the treatment decision. What would be your first treatment option?”, presenting the following options: (a) replacement with a new amalgam restoration, (b) replacement with composite resin restoration, (c) finishing and polishing, and (d) no treatment necessary. Therefore, the treatment of both decayed teeth and ill-fitting amalgam was considered as outcomes for this study.

Co-variables

The questionnaire also addressed sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. In order to avoid any bias due to the presence of the interviewers during the clinical questions, the tablet was handed to the dentist who marked the indicated treatment option. The type of dentist’s office was collected by the interviewers (private personal practice, public health service or private clinics) as well the sex of the dentist. Dentist skin color was noted by the interviewer according to the following categorization: white, yellow, brown, and black (IBGE) [17]. This variable was subsequently separated into white (white and yellow) and black (brown and black) individuals. Time since graduation was collected and assigned to the following categories: 0 to 5 years, six to 15, and more than 15 years. Also, dentists were asked if they had undergone any postgraduate training (yes/no).

Sample size calculation

Calculation of sample size was performed considering a pilot study with dentists who would not be participating in the study. The outcome considered for the calculation of the sample was the indication of prosthetic treatment for a severely impaired tooth. Considering a prevalence of outcome of 81% for white patients and 70% for black individuals, a power of 80 and 5% confidence level, a sample of 524 individuals was obtained. To compensate for losses and refusals, 15% was added to this calculation, making a final sample size of 603 individuals.

Data analysis

The software STATA version 12.0 was used in the analysis. Descriptive analysis was conducted to determine the relative and absolute frequency of the variables of interest. The effect of patient skin color on the dentists’ treatment decision was tested using multinomial logistic regression analysis with robust variance, considering a 95% confidence level. The final models were adjusted for sex, dentist’s skin color, city, place of interview, time since graduation, and postgraduate training.

Ethical issues

The Ethics Committee of the Dental College of the Federal University of Pelotas approved this project (number 1,422,885). All participants signed informed consent forms.

Results

A total of 636 dentists (58.7% female) agreed to participate in the study. Of these, 51.9% received the white patient. In addition, about 55% of the interviews were conducted in individual private practice, 36% in private clinics, and 9% in the public health service (Table 1). The majority of dentists interviewed (34.6%) had graduated over 15 years prior to the interview and 32.8% had graduated less than 5 years before the study. In addition, the vast majority of dentists (82%) had undergone postgraduate training.

Only one dentist declined to participate in the study. He was from the city of Caxias do Sul, working in private personal practice, with time since graduation of 31 years. Some dentists asked for radiographic images before making a decision on the treatment for the first and/or second questions, even after the interviewers stressed that the referral for treatment should be made according to the clinical characteristics of the case. Hence, the number of questions answered for the decayed tooth was 614 and for the ill-fitting amalgam, 615.

Table 2 shows the distribution of outcomes according to patient’s skin color. Referrals for prosthetic treatment for a severely decayed tooth were higher in dentists who received the white patient (85.3 vs 80.9% for the black patient). Referrals for composite restoration for a severely impaired tooth were higher in dentists who received the black patient (12.2 vs 6.8% for the white patient). The treatment decision for ill-fitting amalgam restoration revealed a higher indication of replacement of amalgam with composite resin with the white patient (65.7%) compared with the black individual (61.5%).

A multinomial logistic regression was used to estimate the relative risk ratio (RRR) (Table 3). After adjustment for possible confounders (sex, dentist’s skin color, place of interview, time since graduation, and postgraduate training), using prosthetic treatment as a reference, it was observed that the black patient with the decayed tooth had a 99% higher risk of receiving a direct composite resin restoration (p = 0.027) compared to the white patient, while the indication to extract the tooth was similar for each patient (p = 0.657). Regarding the decision-making for the treatment of ill-fitting amalgam, not considering any particular treatment as a reference category, the black patient exhibited a smaller risk for both the replacement of restoration with composite resin (0.09 95%CI [0.01–0.82]) and finishing and polishing (0.11 95%CI [0.01–0.99]) compared with the white patient.

Discussion

In present study, it was observed that patient skin color influenced the indication of treatments by dentists from different cities and regions of Brazil, even after correction for possible confounders. For both severely decayed teeth and ill-fitting amalgam restorations, dentists chose less complex and cheaper treatment options for the black patient, even when there was no mention of the socioeconomic status of the patient and receiving complete freedom to decide the best treatment option. Although the clinical situation presented here cannot replicate the multifaceted relationship between patient and dentist, our results have shown that skin color played an important role in the treatment decision by dentists.

Professionals may be contributing unconsciously to the propagation and replication of racial discrimination, indicating different treatments according to patient skin color [4, 5, 18]. In fact, several racial disparities are observed [19, 20] in America and Latin America, including Brazil, and they reflect the worse socioeconomic [21] and health conditions for black individuals [22,23,24]. Moreover, it is important to highlight that interactions between income and skin color can have a synergistic effect [25]. Thus, in addition to concentrating the disease in the population, these factors can influence the interventions proposed by health professionals [4, 25]. The different choices of treatment according to the patient’s skin color, as observed in this study, could be explained by the socioeconomic inequalities associated with black individuals [26, 27]. These disparities could lead the dentist to believe that the black patient did not have the financial resources to pay for the treatment. This explanation corroborates the interviewers’ observations in the field work, where they were frequently questioned about the socioeconomic conditions of the black patient, while this never occurs with the white patient, unconsciously revealing a sense of economic disparity between black and white individuals. In the present study, we have opted to omit the socioeconomic status of patients in an effort to avoid bias with the dentist’s decision-making process. Accordingly, dentists were instructed not to consider the patient’s income as a limitation when deciding the treatment option. Nevertheless, dentists indicated cheaper treatments for the black patient.

Socioeconomic status is just one of several factors that may contribute to the disparities observed with regard to the patient’s skin color [6, 26]. A range of sources that promote and maintain social iniquities emerged with economic development, based on slavery, which provide economic advantages resulting in racial stereotypes and, consequently, injustice [20, 28]. Over time, this factor prompted other forms of racial discrepancies linked to the level of education, power, freedom, and prestige [6, 20]. Several of the effects of racism are displayed and can affect the different parameters in the life of individuals [19]. In this context, Pager 2003 observed that discrimination due to skin color could be a greater barrier than having a criminal record when attending job interviews [29]. This study shows that, after a job interview, white men with a criminal record receive more job offers than black men without a criminal record [29]. Discriminatory behavior goes on in more covert forms with different repercussions, also affecting health through numerous mechanisms [30]. Black individuals received less and worse treatment than whites [4, 5, 31, 32], and this seems to be the case even with the correction for socioeconomic status. This underlines the fact that the dynamics of racial discrimination involve a large number of factors which can often not be observed and predicted in these studies [6], because a large proportion of the differences between the ethnic groups occur in a longitudinal fashion, over the lifespan [16].

We observed a high risk for the indication of composite resin restorations in severely decayed teeth with the black patient. However, it is important to consider that the indication of an indirect prosthetic restoration was the most prevalent for both the black and the white patient. Direct restorations with composite resin can be filled in a single, clinical appointment, being more simple and cheaper than prosthetic treatments [33,34,35,36]. Direct restorations have good survival rates in class I and II restorations [36,37,38]. However, when a large portion of the dental structure is already impaired (as in the present study), indirect restorations, such as crowns, seem to provide better survival rates, particularly in the long-term [39]. Although a recent Cochrane review (that includes a 3-year follow-up study) did not observe differences between single crowns and direct restoration for large restorations [40], another systematic review comprising 10 studies observed that survival rates, after 10 years with crowns, were 81%, while direct restorations showed a survival rate of 63% [41]. In fact, prosthetic treatments require more clinical appointments and laboratory work, thus increasing the final cost of treatment, which may have been the predominant factor for clinical longevity.

In a Brazilian study conducted in 2005, it was found that the prevalence of indications to extract decayed teeth was higher in black individuals than in white patients [4]. However, in the present study, the indication to extract teeth was similar for both patients. This fact may be explained by the period when the study was conducted (11 years ago). Nowadays, the decisions to extract have dropped dramatically [42], while in the past, this approach was more frequent [43, 44]. Moreover, in 2004, the Smiling Brazil (Brasil Sorridente) program began, offering complex treatment, such as endodontic treatment, within the public health service [45, 46]. This program led to a change in public oral health services, reaching the whole population, also providing prosthetic treatment [45]. These aspects could explain the differences found in our study, and rather than indicating extraction of decayed teeth, now, dentists prefer to indicate the restoration of composite resin as opposed to crowns for black individuals. A comparison of these results showed that the choice of treatment has moved to a more conservative approach, but dentists still opted for more simple, cheaper procedures when faced with black individuals.

Although not overly significant, the indication of the replacement of ill-fitting amalgam restorations with new amalgam restorations was indicated more for black individuals, while indications for the replacement with composite resin were more prevalent for the white patient, there being a statistical difference. It is important to emphasize that in the present clinical situation, the indication of treatment such as the replacement of restorations with amalgam or composite resin could be construed as overtreatment. Any restoration replacement leads to a loss of a robust dental structure and, without clinical indication, can lead to a repetitive restorative cycle [47]. Moreover, the motivation for the patient to visit the dentist, in the present case, was tooth pain associated with a severely impaired tooth. The clinical case has not mentioned any request of an esthetic nature by the patient that would justify a replacement of amalgam restoration with composite resin. In contemporary society, esthetics play an important role in the life of individuals [48], and both the cosmetic industry and the dental profession have used this facet to increase demand and, consequently, profits.

Accordingly, the black patient was protected from overtreatment, which could be interpreted as a beneficial outcome, when compared to the white patient. However, this decreased risk is probably due to a process of discrimination by the dentist, which demonstrates a clear tendency towards less complex and cheaper treatment options for the black patient. Finishing and polishing of the amalgam restoration was the more conservative approach for restoring the function of teeth as well as being a cheaper treatment. In this way, we observed that, in the clinical case of the black patient, the indication of this treatment was also less than for white-skinned individuals. Therefore, although the black skin color has been a protective factor against overtreatment, it was also associated with less frequent indication of the more recommended, conservative option, the option not to receive any treatment at all being more prevalent than for whites, reinforcing the presence of racial discrimination in health outcomes [6, 7, 14, 20, 49, 50].

To reduce possible bias in the study, we conducted face-to-face interviews to answer the potential questions of the clinicians and reduce the probability of incomplete or wrong answers. It was, therefore, possible to obtain a high response rate. Moreover, we carried out the study in four cities in two different regions of Brazil. Brazil is a multifaceted country, with huge variability of culture and marked differences in terms of racial distribution between regions. The Northeast region has a high proportion of blacks compared to the Southern region of the country, which could influence the perception and discrimination of the population with regard to skin color [17]. Although results were not shown in this article, there was no difference between regions in terms of treatment decision, emphasizing that racial discrimination is a problem affecting most of the country. Moreover, it is important to highlight that the decision-making process can be different from country to country, depending on the diagnostic criteria, treatment options available, and even the competitiveness of the labor market. Although X-rays could facilitate treatment options, the present study has provided sufficient information in respect of the decision-making process for dentists in Brazil, in both private and public practice. These results could not be reproduced in a country with a different culture and different treatment options. In addition, it should be mentioned that Brazil possesses around 20% of all the world’s dentists [51]. This situation leads to a very competitive labor market, which can result in the indication of overtreatment by dentists in order to increase their profits [51]. We would highlight the importance of including the discussion of racial discrimination and inequality in the curriculum of the dental schools, since the first step to eliminating racial discrepancies is to accept that they exist and discuss possible ways to minimize them.

Conclusion

Patient skin color influenced the dentist’s choice of treatment.

References

Chisini LA, Conde MC, Correa MB, Dantas RV, Silva AF, Pappen FG, Demarco FF (2015) Vital pulp therapies in clinical practice: findings from a survey with dentist in southern Brazil. Braz Dent J 26:566–571. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6440201300409

Schwendicke F, Meyer-Lueckel H, Dorfer C, Paris S (2013) Attitudes and behaviour regarding deep dentin caries removal: a survey among German dentists. Caries Res 47:566–573. https://doi.org/10.1159/000351662

Demarco FF, Baldissera RA, Madruga FC, Simoes RC, Lund RG, Correa MB, Cenci MS (2013) Anterior composite restorations in clinical practice: findings from a survey with general dental practitioners. J Appl Oral Sci 21:497–504. https://doi.org/10.1590/1679-775720130013

Cabral ED, Caldas Ade F Jr, Cabral HA (2005) Influence of the patient's race on the dentist’s decision to extract or retain a decayed tooth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 33:461–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00255.x

Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, Kerner JF, Sistrunk S, Gersh BJ, Dube R, Taleghani CK, Burke JE, Williams S, Eisenberg JM, Escarce JJ (1999) The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med 340:618–626. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199902253400806

Phelan J, Link B (2015) Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annu Rev Sociol 41:311–330

Sabbah W, Tsakos G, Chandola T, Sheiham A, Watt RG (2007) Social gradients in oral and general health. J Dent Res 86:992–996. https://doi.org/10.1177/154405910708601014

Dalazen CE, De Carli AD, Bomfim RA, Dos Santos ML (2016) Contextual and individual factors influencing periodontal treatment needs by elderly Brazilians: a multilevel analysis. PLoS One 11:e0156231. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156231

Vettore MV, Marques RA, Peres MA (2013) Social inequalities and periodontal disease: multilevel approach in SBBrasil 2010 survey. Rev Saude Publica 47(Suppl 3):29–39

Schwendicke F, Dorfer CE, Schlattmann P, Foster Page L, Thomson WM, Paris S (2015) Socioeconomic inequality and caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent Res 94:10–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034514557546

Correa MB, Peres MA, Peres KG, Horta BL, Barros AJ, Demarco FF (2013) Do socioeconomic determinants affect the quality of posterior dental restorations? A multilevel approach. J Dent 41:960–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2013.02.010

Peres MA, Peres KG, de Barros AJ, Victora CG (2007) The relation between family socioeconomic trajectories from childhood to adolescence and dental caries and associated oral behaviours. J Epidemiol Community Health 61:141–145. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.044818

Mielck A, Vogelmann M, Leidl R (2014) Health-related quality of life and socioeconomic status: inequalities among adults with a chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 12:58. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-58

Hunt B, Whitman S (2015) Black: white health disparities in the United States and Chicago: 1990-2010. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2:93–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-014-0052-0

Franks P, Muennig P, Lubetkin E, Jia H (2006) The burden of disease associated with being African-American in the United States and the contribution of socio-economic status. Soc Sci Med 62:2469–2478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.035

Do DP, Frank R, Finch BK (2012) Does SES explain more of the black/white health gap than we thought? Revisiting our approach toward understanding racial disparities in health. Soc Sci Med 74:1385–1393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.048

IBGE (2013) Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Ethnic-racial Population Characteristics: Classifications and identities. Available in 07/27/2017 in: http://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv63405.pdf

Baumgarten A, Bastos JL, Toassi RFC, Hilgert JB, Hugo FN, Celeste RK (2018) Discrimination, gender and self-reported aesthetic problems among Brazilian adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 46:24–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12324

Ben J, Jamieson LM, Priest N, Parker EJ, Roberts-Thomson KF, Lawrence HP, Broughton J, Paradies Y (2014) Experience of racism and tooth brushing among pregnant aboriginal Australians: exploring psychosocial mediators. Community Dent Health 31:145–152

Bastos JL, Celeste RK, Paradies YC (2018) Racial inequalities in oral health. J Dent Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034518768536

Williams DR, Collins C (2001) Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep 116:404–416. https://doi.org/10.1093/phr/116.5.404

Williams DR (1999) Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination. Ann N Y Acad Sci 896:173–188

Yoo W, Kim S, Huh WK, Dilley S, Coughlin SS, Partridge EE, Chung Y, Dicks V, Lee JK, Bae S (2017) Recent trends in racial and regional disparities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality in United States. PLoS One 12:e0172548. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172548

Freire Mdo C, Reis SC, Figueiredo N, Peres KG, Moreira Rda S, Antunes JL (2013) Individual and contextual determinants of dental caries in Brazilian 12-year-olds in 2010. Rev Saude Publica 47(Suppl 3):40–49

Chisini LA (2017) Evaluation of factors that influencing amalgam restorations replacment by composite resins in posterior teeth in the life course: a study in a birth cohort. Dissertation, Federal University of Pelotas

Paradies Y (2016) Whither anti-racism? Ethn Racial Stud 39:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1096410

Finlayson T, Lemus H, Becerra K, Kaste L, Beaver S, Salazar C, Singer R, Youngblood M (2018) Unfair Treatment and Periodontitis Among Adults in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 11

Feagin J (2000) Racist America: roots, current realities, and future reparations. Routledge, New York

Pager D (2003) The mark of a criminal record. Am J Sociol 108:937–975

Jamieson LM, Steffens M, Paradies YC (2013) Associations between discrimination and dental visiting behaviours in an aboriginal Australian birth cohort. Aust N Z J Public Health 37:92–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12018

Alexander GC, Sehgal AR (1998) Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women, and the poor. JAMA 280:1148–1152

Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, Epstein AM (1999) The effect of patients’ preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 341:1661–1669. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199911253412206

Manhart J, Chen H, Hamm G, Hickel R (2004) Buonocore memorial lecture. Review of the clinical survival of direct and indirect restorations in posterior teeth of the permanent dentition. Oper Dent 29:481–508

Morimoto S, Rebello de Sampaio FB, Braga MM, Sesma N, Ozcan M (2016) Survival rate of resin and ceramic inlays, onlays, and overlays: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent Res 95:985–994. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034516652848

Angeletaki F, Gkogkos A, Papazoglou E, Kloukos D (2016) Direct versus indirect inlay/onlay composite restorations in posterior teeth. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 53:12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2016.07.011

Chisini LA, Collares K, Cademartori MG, de Oliveira LJC, Conde MCM, Demarco FF, Correa MB (2018) Restorations in primary teeth: a systematic review on survival and reasons for failures. Int J Paediatr Dent 28:123–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/ipd.12346

Da Rosa Rodolpho PA, Donassollo TA, Cenci MS, Loguercio AD, Moraes RR, Bronkhorst EM, Opdam NJ, Demarco FF (2011) 22-Year clinical evaluation of the performance of two posterior composites with different filler characteristics. Dent Mater 27:955–963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2011.06.001

Demarco FF, Correa MB, Cenci MS, Moraes RR, Opdam NJ (2012) Longevity of posterior composite restorations: not only a matter of materials. Dent Mater 28:87–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2011.09.003

Stavropoulou AF, Koidis PT (2007) A systematic review of single crowns on endodontically treated teeth. J Dent 35:761–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2007.07.004

Sequeira-Byron P, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B, Nasser M, Alrowaili EF (2015) Single crowns versus conventional fillings for the restoration of root-filled teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD009109. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009109.pub3

Nagasiri R, Chitmongkolsuk S (2005) Long-term survival of endodontically treated molars without crown coverage: a retrospective cohort study. J Prosthet Dent 93:164–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.11.001

Zachar J (2015) Should retention of a tooth be an important goal of dentistry? How do you decide whether to retain and restore a tooth requiring endodontic treatment or to extract and if possible replace the tooth? Aust Endod J 41:2–6

Brennan DS, Spencer AJ (2006) Longitudinal comparison of factors influencing choice of dental treatment by private general practitioners. Aust Dent J 51:117–123

Warren JJ, Hand JS, Levy SM, Kirchner HL (2000) Factors related to decisions to extract or retain at-risk teeth. J Public Health Dent 60:39–42

Pucca GA Jr, Gabriel M, de Araujo ME, de Almeida FC (2015) Ten years of a National Oral Health Policy in Brazil: innovation, boldness, and numerous challenges. J Dent Res 94:1333–1337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034515599979

Pires A, Gruendemann J, Figueiredo G, Conde M, Corrêa M, Chisini L (2015) Secondary oral health care in the state of Rio Grande do Sul: descriptive analysis of the specialized production in cities with dental specialty centers from the outpatient information system of the unified health system. Revista da Faculdade de odontologia - UPF 20:325–333. https://doi.org/10.5335/rfo.v20i3.5407

Elderton RJ (1988) Restorations without conventional cavity preparations. Int Dent J 38:112–118

Silva FBD, Chisini LA, Demarco FF, Horta BL, Correa MB (2018) Desire for tooth bleaching and treatment performed in Brazilian adults: findings from a birth cohort. Braz Oral Res 32:e12. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107bor-2018.vol32.0012

Calvasina P, Muntaner C, Quinonez C (2015) The deterioration of Canadian immigrants’ oral health: analysis of the longitudinal survey of immigrants to Canada. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 43:424–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12165

Lawrence HP, Cidro J, Isaac-Mann S, Peressini S, Maar M, Schroth RJ, Gordon JN, Hoffman-Goetz L, Broughton JR, Jamieson L (2016) Racism and oral health outcomes among pregnant Canadian aboriginal women. J Health Care Poor Underserved 27:178–206. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2016.0030

San Martin A, Chisini L, Martelli S, Sartori L, Ramos E, Demarco F (2018) Distribution of dental schools and dentists in Brazil: an overview of the labor market. Revista da Abeno. https://doi.org/10.30979/rev.abeno.v18i1.399

Stefanac SJ (2007) CHAPTER 3 - Developing the treatment plan. In: Treatment planning in dentistry, 2nd edn. Mosby, Saint Louis, pp 53–68

Funding

The work was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee of the Dental College of the Federal University of Pelotas approved this project (number of 1,422,885).

Informed consent

All participants signed informed consent forms.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chisini, L.A., Noronha, T.G., Ramos, E.C. et al. Does the skin color of patients influence the treatment decision-making of dentists? A randomized questionnaire-based study. Clin Oral Invest 23, 1023–1030 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2526-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2526-7