Abstract

Postpartum depression affects approximately 11% of women. However, screening for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMAD) is rare and inconsistent among healthcare professionals. When healthcare professionals screen, they often rely on clinical judgment, rather than validated screening tools. The objective of the current study is to review the types and effectiveness of interventions for healthcare professionals that have been used to increase the number of women screened and referred for PMAD. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses was utilized to guide search and reporting strategies. PubMed/Medline, PsychInfo/PsychArticles, Cumulative Index to Nursing, Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition databases were used to find studies that implemented an intervention for healthcare professionals to increase screening and referral for PMAD. Twenty-five studies were included in the review. Based on prior quality assessment tools, the quality of each article was assessed using an assessment tool created by the authors. The four main outcome variables were the following: percentage of women screened, percentage of women referred for services, percentage of women screened positive for PMAD, and provider knowledge, attitudes, and/or skills concerning PMAD. The most common intervention type was educational, with others including changes in electronic medical records and standardized patients for training. Study quality and target audience varied among the studies. Interventions demonstrated moderate positive impacts on screening completion rates, referral rates for PMAD, and patient-provider communication. Studies suggested positive receptivity to screening protocols by mothers and providers. Given the prevalence and negative impacts of PMAD on mothers and children, further interventions to improve screening and referral are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMAD) is an overarching term for any mood or anxiety disorder diagnosed (Thiam and Weis 2017) while pregnant or up to 1 year postpartum (Gaynes et al. 2005). PMAD is a broad category that includes, but is not limited to, postpartum depression (PPD), perinatal depression, and postpartum anxiety. PMAD encompasses diagnosed psychopathology (e.g., major depressive disorder) and other dimensions of psychological distress. Symptoms include crying more often than usual, feelings of anger, withdrawing from loved ones, feeling numb or disconnected from the baby, feeling guilt about not being a good mom, loss of energy, irritability, and hopelessness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2017). While the terminology PPD has historically been used to discuss maternal mental health concerns, the current review uses the term PMAD to reflect contemporary literature. However, PPD is still used if there is an obvious distinction between PPD and PMAD in the context of a study. Within a diagnostic framework, PPD is diagnosed as a major depressive disorder with peripartum onset, which is the most recent episode occurring during pregnancy or in the 4 weeks following delivery (American Psychiatric Association 2013). PPD affects approximately 11% of women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2017). Moreover, some reports have estimated the prevalence of PPD to be as high as 40–60% among low-income and teenage mothers (Earls and Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health 2010).

What do we know about PMAD?

PMAD has been shown to have negative effects on the mother, child, and the mother-child relationship. For instance, Lovejoy et al. (2000) reported that mothers with PPD exhibited more negative and disengaged behavior towards their children compared to their non-depressed counterparts. Also, mothers with PPD touch their infants less and in a less affectionate manner than non-depressed mothers (Ferber et al. 2008). Infants of depressed mothers are less likely to be securely attached (Martins and Gaffan 2000). Depressed mothers are less likely to put their infant to sleep in the back position, have a lower likelihood of ever breastfeeding, and are more likely to put the child to bed with a bottle (Paulson et al. 2006). A meta-analysis by Goodman et al. (2011) indicated that maternal depression was related to children’s higher levels of internalizing, externalizing, and general psychopathology in small magnitude. Likewise, maternal depression was related to negative affect and behavior and lower levels of positive affect and behavior in children (Goodman et al. 2011).

There are several known risk factors exacerbating susceptibility to PMAD. Risk factors for developing PMAD include a history of depression or anxiety (Gaillard et al. 2014), low marital satisfaction (Escribà-Agüir and Artazcoz 2011), domestic violence (Ahmed et al. 2012), lack of social support (Eastwood et al. 2012), and isolation (Eastwood et al. 2012). In addition, positive depression screens have been associated with later increased rates of suicidal ideation (Bodnar-Deren et al. 2016), indicating a need to screen and refer perinatal women for further evaluation and treatment.

Screening and referral for treatment for those with PMAD

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends screening for depression and anxiety symptoms at least once during the perinatal period using a standardized, validated tool (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2015). The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends incorporating the Edinburgh Postnatal Scale into the 1, 2, 4, and 6 month visits (Earls and Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health 2010). The AAP also endorses using a cut score of 10 on the EPDS as an indicator of risk that depression is present (Earls and Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health 2010). These guidelines by leading professional organizations indicate the importance of screening by a variety of healthcare professionals.

Screening rates for PMAD are inconsistent and low among healthcare professionals in the USA (Evans et al. 2015). A systematic review by Evans et al. (2015) demonstrated that among seven studies, an average of only 55% of healthcare professionals ever, sometimes, often, or always assess for PPD. When healthcare professionals do assess women for PMAD, the most common method of assessment is clinical judgment. Pediatricians are most likely to use clinical assessment (80%), as opposed to a validated screening tool (Connelly et al. 2007; Heneghan et al. 2007; Wiley et al. 2004). However, Heneghan and colleagues (2000) have shown pediatricians demonstrate poor accuracy in recognizing elevated levels of depressive symptoms without a validated screening tool during the postpartum period (e.g., sensitivity = 29%, specificity = 81%). Moreover, 60% of OB/GYNs rely on clinical assessment (Chadha-Hooks et al. 2010; Leddy et al. 2011). This finding echoes a larger general trend in documented limitations in the accuracy of health professionals’ clinical judgment when assessing mental health concerns (e.g., Lopez et al. 2017; Neal and Brodsky 2016). Screening for PMAD is generally recognized as a way to improve depression outcomes (Georgiopoulos et al. 2001).When obstetricians recognize a woman’s PMAD, referral and treatment rates are fairly high during the prenatal period (80%) and postpartum period (93.7%) (Goodman and Tyer-Viola 2010). However, when women screen positive for PMAD but the obstetrician is unaware of the positive screen, referral and treatment rates are low during the prenatal period (33%) and postpartum period (27.5%). The noted results indicate a need for systematic approach to screening for PMAD and use of results to increase treatment and referral rates for women suffering from PMAD. A review of the sensitivity and specificity of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), a commonly used perinatal depression screening tool, demonstrated that sensitivity of the scales ranges from 65–100% while specificity ranges from 49 to 100% during the postpartum period (Eberhard-Gran et al. 2001). The EPDS has adequate reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 (Cox et al. 1987). Due to providers’ inconsistency in clinical judgment, as well as strong psychometric properties of the EPDS, screening tools should be used to adequately assess PMAD.

The present review

A lack of screening and referral for treatment of PMAD demonstrates a need to assess interventions for healthcare professionals to increase screening and, therefore, referral rates for behavioral health treatment for women with PMAD. Likewise, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers PMAD a common and serious illness in the USA (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2017). The current review aims to (1) summarize and describe the literature concerning implementation of an intervention for healthcare professionals (e.g., pediatricians, obstetricians, nurses) to increase PMAD screening rates and, in instances of positive screens, behavioral health referrals and (2) review the effectiveness of the noted interventions. To our knowledge, there have been no systematic reviews investigating such interventions for healthcare professionals.

Methods

Search strategy

Articles included in the current review were identified through searches of the following databases: PubMed, Medline, PsychInfo, PsychArticles, CINAHL, and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition. Additional relevant articles were found through article introduction or reference sections. Each database was searched from 1994 to 2017 because the postpartum specifier was introduced in 1994 in the DSM-IV (Segre and Davis 2013).

Selection criteria

Articles were included if they were performed in the USA, in English, peer-reviewed, used human subjects, and described original data. Intervention search terms were not included as to capture the broad scope of interventions. Search terms are shown in Table 1. Articles were included if they screened or referred women for PMAD during pregnancy or up to 1 year postpartum. Studies were also included with any medical provider as the target audience of the intervention (e.g., nurse, nurse practitioner, obstetrician, family physician). See Table 3 for a full list of target audiences of the interventions. Case studies and non-peer-reviewed articles were excluded to ensure rigor. Studies performed outside of the USA were excluded.

Study selection

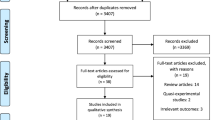

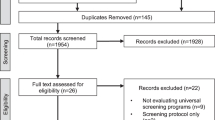

PRISMA was utilized to guide search and reporting strategies of the current review (Moher et al. 2009). The flow chart of study selection resulting in the 25 articles is shown in Fig. 1.

Assessment of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders

PMAD was defined as any form of depression or anxiety during pregnancy or up to 1 year postpartum (Gaynes et al. 2005). Others have defined the onset of postpartum timeframe as short as 4 weeks postpartum (American Psychiatric Association 2013), but the current review takes a more conventional approach to the onset timeframe in order to provide a more comprehensive review. PMAD ranged from symptom report instruments to clinical diagnosis. Any diagnostic version of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders was included (e.g., PPD, postpartum anxiety, peripartum depression).

Assessment of intervention

An intervention was defined as any tool or method aimed at increasing provider screening rates, treatment and referral rates, knowledge of PMAD, or confidence in assessing and referring for PMAD. Interventions included, but were not limited to, educational interventions (e.g., presentation, conference), systematic changes in electronic medical records, and use of a standardized patient training exercise.

Assessment of outcome

Outcomes included any variable addressing screening rates, treatment and referral rates, rates of positive PMAD screeners, and provider PMAD assessment-related knowledge, attitudes, and skills.

Quality assessment

Based on prior assessment tools of quality (Downs and Black 1998; Effective Public Health Practice Project 1998), the quality of each article was assessed using a 26-question assessment tool created by the authors. The assessment tool is shown in Online Supplement A. Items are separated into three sections: introduction, methods, and results. A point system was used to assess the quality of each article. High scores indicate a higher quality study and possible scores range from 1 to 32. To ensure the reliability of ratings, the quality assessment tool was used by two authors (Jenkins and Long) to assess each of the final 25 selected articles. The two coders began by assessing five articles independently. Intraclass correlations were then conducted and any items with coefficients under .70 were revised for clarity in definition. Jenkins and Long then completed the same process in three successive iterations to ensure the intraclass coefficients were above .70 (i.e., above acceptable inter-rater agreement values; Bakeman and Gottman 1997, Koo and Li 2016). After each iteration of coding, the coders communicated regarding differences in results and clarified any discrepancies. By the last iteration of coding, all intraclass coefficients achieved .70 or above.

Results

Quality assessment summary

The results of the quality assessment tool are shown in Table 2. Most studies provided comprehensive and clear information regarding the intervention for healthcare providers to improve PMAD screening and referral.

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 25 selected studies are shown in Table 3. Quality assessment total scores ranged from 6 to 23 among the 25 selected studies, indicating a broad scope of article quality in the literature regarding interventions for healthcare professionals to improve screening, treatment, and referral practices for PMAD.

PMAD measurement tool

The majority of studies (N = 14, 56%) used the EPDS (Cox et al. 1987), to measure PMAD symptoms. Other PMAD measurement tools include the PHQ-2 (N = 2, 8%) (Kroenke et al. 2003), PHQ-9 (N = 3, 12%) (Kroenke et al. 2001), and the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID; N = 1, 4%) (First 1997). One study used a two-question screen endorsed by the US Preventive Services Task Force (Olson et al. 2005). One study used the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) two-question screen. One study used the PPDS.

Intervention type

All studies implemented an intervention to improve screening, treatment, or referral rates for PMAD. The majority of the studies (N = 21, 84%) implemented an educational intervention. Two (8%) studies implemented a change in electronic medical records (EMRs) as the intervention. Two (8%) studies implemented a training program involving a standardized patient exercise. Two (8%) studies began using an established screening protocol with research nurses. One (4%) study sent out reminders of screening protocol to providers via email, meetings, and in-services as the intervention.

Intervention target audience

The target audience for the intervention was heterogeneous across studies. Seven (28%) interventions targeted providers in the obstetric field. Five (20%) interventions targeted providers in the pediatric field. Two studies (8%) were aimed at healthcare providers in both the obstetric and pediatric fields. Three (12%) interventions were aimed at primary care or family practice healthcare professionals. Two (8%) were aimed at intervening with medical students while 1 (4%) was developed for research nurses. Two (8%) were targeted at all levels of professionals in the healthcare field while 1 (4%) was aimed at maternity unit health professionals. One (4%) intervention was aimed at nurses and healthcare providers in an adolescent maternity program and 1 (4%) was aimed at paraprofessionals and nurses.

Outcome variable(s)

Four key outcome variables, and a total of 63, were present among the 25 selected studies along with other study-specific outcomes. The four main outcome variables were the following: percentage of women screened for PMAD (N = 13, 20.63%), percentage of women referred for services (N = 9, 14.29%), percentage of women screened positive for PMAD (N = 16, 25.40%), and provider knowledge, attitudes, and/or skills (e.g., PMAD screening priority, PMAD screening burden level, knowledge of PMAD support groups and resources) (N = 10, 15.87%). Other outcome variables presented were the following: staff and provider feedback of screening program (N = 2, 3.17%), participant mental health service use (N = 1, 1.59%), mother and healthcare provider satisfaction with program assistance and mental health advisors (N = 1, 1.59%), staff and provider familiarity of screening program (N = 1, 1.59%), detection of PMAD (N = 2, 3.17%), qualitative data regarding acceptability of the screening approach to mothers and healthcare providers (N = 1, 1.59%), risk factors for developing PMAD (N = 2, 3.17%), comfort level with PPD and postpartum self-care (N = 1, 1.59%), frequency of use of a web-based education tool for PMAD statistics (N = 1, 1.59%), registered users of the education for PMAD tool (N = 1, 1.59%), education tool user rating of modules (N = 1, 1.59%), average EPDS score (N = 1, 1.59%), depression diagnosis after a positive screen (N = 1, 1.59%), type of treatment (N = 2, 3.17%), and accuracy of EPDS scoring (N = 1, 1.59%).

Overview of intervention impact

The three main intervention types (i.e., education, EMR, standardized patient exercises) were reviewed for their impact on outcome variables. Twenty of the 25 articles included in the current review evaluated relative impact on some type of outcome. Studies that implemented an educational intervention reported screening completion rates ranging from 39 to 100% (Avalos et al. 2016; Chaudron et al. 2004; Gordon et al. 2006; Lind et al. 2017; Olson et al. 2005; Schaar and Hall 2013; Segre et al. 2014; Yawn et al. 2012). Similarly, studies that implemented an educational intervention reported positive screening rates, indicating a potential depressive disorder range from 4.4 to 29.5% (Avalos et al. 2016; Baker-Ericzen et al. 2008; Chaudron et al. 2004; Gordon et al. 2006; Lind et al. 2017; Mancini et al. 2007; Olson et al. 2005; Schaar and Hall 2013; Segre et al. 2014; Smith and Kipnis 2012). Women who received referral or treatment from their healthcare provider ranged from 62 to 100% (Baker-Ericzen et al. 2008; Gordon et al. 2006; Olson et al. 2005). Of the nine pre-post design studies (Avalos et al. 2016; Baker-Ericzen et al. 2008; Bauer et al. 2009; Chaudron et al. 2004; Olson et al. 2005; Schaar and Hall 2013; Schillerstrom et al. 2013; Smith and Kipnis 2012; Yonkers et al. 2009), detection of depression and referral for treatment increased from pre- to post-educational program. Thirteen studies used post-intervention examination only (Feinberg et al. 2006; Gordon et al. 2006; Horowitz et al. 2011; Mancini et al. 2007; Osborn 2012; Rowan et al. 2012; Segre et al. 2014; Sheeder et al. 2009; Talmi et al. 2009; Thomason et al. 2010; Tucker et al. 2004; Venkatesh et al. 2016; Wisner et al. 2008). There was positive receptivity to the screening protocol by both mothers (Olson et al. 2005) and providers (Baker-Ericzen et al. 2008; Feinberg et al. 2006; Schaar and Hall 2013).

Of the two studies that implemented a change in EMR as the intervention, results indicated that providers administered the EPDS 98% of the time and referred mothers with positive screens 100% of the time (Sheeder et al. 2009). Results also indicated that screening for PMAD was not burdensome and opened up new opportunities for discussion between patient and provider (Feinberg et al. 2006). Overall, of the two studies that implemented changes in EMR as the intervention, results indicate positive changes in patient-provider communication. Of the two studies that implemented a standardized patient exercise, the percent of women screened for PMAD ranged from 39 to 100% (Baker-Ericzen et al. 2008). Also, students found the standardized patient session to be useful, it held their interest, and rated it as excellent or near excellent (Tucker et al. 2004). Overall, studies that implemented a standardized patient exercise as the intervention, results indicated positive receptivity to the exercise. Intervention findings need to be viewed with caution in light of the majority (e.g., Feinberg et al. 2006; Gordon et al. 2006; Segre et al. 2014; Tucker et al. 2004) only conducting post-intervention assessment (i.e., limited rigor) and that some outcomes still varied widely in terms of positive outcomes (e.g., rate of screening completion post-educational intervention).

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to summarize and describe studies that implemented an intervention for healthcare professionals to increase screening and referral rates for PMAD. The 25 selected studies demonstrated heterogeneous interventions to improve screening and referral for PMADs. While most interventions included an education piece, other interventions focused on changes in EMRs, standardized patients, established protocol with a research nurse, or healthcare provider reminders of the screening protocol. Educational intervention type also varied widely, including conferences, 45-min meetings, educational website development, and seminars, among others. Educational material in the interventions included symptoms of PMAD, detection tools, treatment options, crisis situations, and impact of PMAD on mothers and children. There were also a variety of target audiences of the intervention including obstetrician and pediatric healthcare professionals, primary care healthcare professionals, medical students, research nurses, maternity unit healthcare professionals, and paraprofessionals.

The PMAD measurement tool most often used was the EPDS. The four main outcome variables utilized in the 25 selected studies were percentage of women screened, percentage of women referred for services, percentage of women screened positive for PMAD, and knowledge, attitudes, and/or skills. The quality of the articles varied widely from very high quality (e.g., Baker-Ericzen et al. 2008; Chaudron et al. 2004) to lower quality (e.g., Baker et al. 2009) based on our quality assessment tool. Several studies did not address the validity of the PMAD measurement tools used. It is important to address validity of measurement tools to reduce bias (Marshall et al. 2000).

One key methodological weakness of the current literature is the lack of pre-post intervention assessments. Fourteen of the 25 reviewed articles implemented no assessment or post-intervention assessment only. Intervention findings need to be viewed with caution in light of the methodological weaknesses. The three main intervention types (i.e., education, change in EMR, standardized patient exercise) were evaluated for the intervention impact. Results from studies that implemented an educational intervention indicated modest positive effects on screening completion rates, referral rates, and receptivity to screening protocol by mothers and healthcare providers. Results from studies that implemented a change in EMRs indicated improvement in patient-provider communication. Results from studies that implemented a standardized patient indicate positive receptivity to the training tool. Overall, results suggest that screening is feasible and may have positive effects on screening completion rates, referral for treatment for PMAD, and improved patient-provider communication. Of course, such positive gains are tempered by the very small total number of studies (e.g., only two addressing EMR) and limited pre-post or randomized designs.

Current studies suggest PMAD is a substantial issue for expecting and new mothers. However, literature also suggests screening and referral rates are low for PMAD (Evans et al. 2015; Goodman and Tyer-Viola 2010; Horowitz and Cousins 2006) and the current review demonstrates a need for an effective and widely used intervention to improve PMAD screening and referral rates, as well as subsequent patient-oriented health outcomes. With only 25 articles aimed at interventions for healthcare professionals to increase screening and referral rates for PMAD, more studies are needed to assess the usefulness and feasibility of these types of interventions and others.

Limitations

There are three main limitations to the current review. First, PMAD definitions and assessment varied across studies. Some studies measured PMAD with self-report questionnaires (e.g., Baker-Ericzen et al. 2008; Rowan et al. 2012) while others did not measure PMAD at all (e.g., Thomason et al. 2010; Tucker et al. 2004). Others used the PHQ-2 or PHQ-9 (e.g., Olson et al. 2005; Yawn et al. 2012) or clinical interview assessments (Horowitz et al. 2011). The variability between studies limits comparison of study results. Second, outcome variables were heterogeneous between studies. Sixty-three different indicators of outcome variables were presented in the 25 studies. Third, we were not able to assess the effectiveness of interventions due to the heterogeneity of PMAD definitions and lack of sufficient number of pre-post assessment designs.

Implications

There are several implications for future research that are informed by the current study. First, future studies should assess PMAD using validated and reliable screening tools designed for the perinatal population, such as the EPDS. Such psychometrically supported tools would enhance both the rigor and convergence of future PMAD research. Second, studies should be inclusive of many healthcare professionals when implementing an intervention, potentially examining differences in PMAD-related competency and behaviors by type of professional. Third, studies should be inclusive and clear about the outcome variables. Given the prevalence and negative impact of PMAD on mother and child, further interventions to improve screening and referral are needed among all disciplines of healthcare. Fourth, given the methodological limitations of current literature, future studies should utilize pre- and post-intervention assessments to enhance the rigorous testing of available types of interventions. Future research should consider the use of education, change in EMR, and standardized patient exercises as potential interventions to improve screening and referral for PMAD. Finally, studies performed in the USA should be compared to results found outside of the USA to evaluate our effectiveness and improve our current PMAD screening, referral, and treatment practices.

References

Ahmed HM, Alalaf SK, Al-Tawil NG (2012) Screening for postpartum depression using Kurdish version of Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Arch Gynecol Obstet 285(5):1249–1255

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2015) Screening for perinatal depression. Committee opinion no. 630. Obstet Gynecol 125:1268–1271

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing

Avalos LA, Raine-Bennett T, Chen H, Adams AS, Flanagan T (2016) Improved perinatal depression screening, treatment, and outcomes with a universal obstetric program. Obstet Gynecol 127(5):917–925

Bakeman R, Gottman JM (1997) Assessing observer agreement. In: Observing interaction: an introduction to sequential analysis, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 56–80

Baker CD, Kamke H, O’hara MW, Stuart S (2009) Web-based training for implementing evidence-based management of postpartum depression. J Am Board Fam Med 22(5):588–589

Baker-Ericzen MJ, Mueggenborg MG, Hartigan P, Howard N, Wilke T (2008) Partnership for women’s health: a new-age collaborative program for addressing maternal depression in the postpartum period. Fam, Syst & Health 26(1):30–44

Bauer SC, Smith PJ, Chien AT, Berry AD, Msall M (2009) Educating pediatric residents about developmental and social–emotional health. Infants & Young Children 22(4):309–320

Bodnar-Deren S, Klipstein K, Fersh M, Shemesh E, Howell EA (2016) Suicidal ideation during the postpartum period. J Women's Health 25(12):1219–1224

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2017, February 15) Depression among women. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/depression/index.htm

Chadha-Hooks PL, Park JH, Hilty DM, Seritan AL (2010) Postpartum depression: an original survey of screening practices within a healthcare system. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 31(3):199–205

Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Kitzman H, Wadkins HI, Conwell Y (2004) Detection of postpartum depressive symptoms by screening at well-child visits. Pediatr 113(3):551–558

Connelly CD, Baker MJ, Hazen AL, Mueggenborg MG (2007) Pediatric health care providers’ self-reported practices in recognizing and treating maternal depression. Pediatr Nurs 33(2):165–172

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British J Psychiatry 150(6):782–786

Downs SH, Black N (1998) The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomized and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 52:377–384

Earls MF, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health (2010) Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatr 126(5):1032–1039

Eastwood JG, Jalaludin BB, Kemp LA, Phung HN, Barnett BE (2012) Relationship of postnatal depressive symptoms to infant temperament, maternal expectations, social support and other potential risk factors: findings from a large Australian cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 12(1):148

Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Tambs K, Opjordsmoen S, Ove Samuelsen S (2001) Review of validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 104(4):243–249

Effective Public Health Practice Project. (1998). Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Hamilton, ON: Effective Public Health Practice Project. Retrieved from: http://www.ephpp.ca/index.html

Escribà-Agüir V, Artazcoz L (2011) Gender differences in postpartum depression: a longitudinal cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health 65(4):320–326

Evans MG, Phillippi S, Gee RE (2015) Examining the screening practices of physicians for postpartum depression: implications for improving health outcomes. Womens Health Issues 25(6):703–710

Feinberg E, Smith MV, Morales MJ, Claussen AH, Smith DC, Perou R (2006) Improving women’s health during internatal periods: developing an evidenced-based approach to addressing maternal depression in pediatric settings. J Women's Health 15(6):692–703

Ferber SG, Feldman R, Makhoul IR (2008) The development of maternal touch across the first year of life. Early Hum Dev 84(6):363–370

First MB (1997) Structured clinical interview for the DSM-IV axis I disorders: SCID-I/P, version 2.0. New York: Biometrics Research Dept., New York State Psychiatric Institute

Gaillard A, Le Strat Y, Mandelbrot L, Keïta H, Dubertret C (2014) Predictors of postpartum depression: prospective study of 264 women followed during pregnancy and postpartum. Psychiatry Res 215(2):341–346

Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr KN, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, Brody S, Miller WC (2005) Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes: Summary

Georgiopoulos AM, Bryan TL, Wollan P, Yawn BP (2001) Routine screening for postpartum depression. J Family Practice 50(2):117–117

Goodman JH, Tyer-Viola L (2010) Detection, treatment, and referral of perinatal depression and anxiety by obstetrical providers. J Women's Health 19(3):477–490

Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D (2011) Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 14(1):1–27

Gordon TE, Cardone IA, Kim JJ, Gordon SM, Silver RK (2006) Universal perinatal depression screening in an Academic Medical Center. Obstet Gynecol 107(2, Part 1):342–347

Heneghan AM, Chaudron LH, Storfer-Isser A, Park ER, Kelleher KJ, Stein RE, Horwitz SM (2007) Factors associated with identification and management of maternal depression by pediatricians. Pediatr 119(3):444–454

Horowitz JA, Cousins A (2006) Postpartum depression treatment rates for at-risk women. Nurs Res 55(2):S23–S27

Horowitz JA, Murphy CA, Gregory KE, Wojcik J (2011) A community-based screening initiative to identify mothers at risk for postpartum depression. J Obstet, Gynecol, Neonatal Nurs 40(1):52–61

Koo TK, Li MY (2016) A guideline for selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropractic Medicine 15:155–163

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Gen Intern Med 16:606–613

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2003) The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 41(11):1284–1292

Leddy M, Haaga D, Gray J, Schulkin J (2011) Postpartum mental health screening and diagnosis by obstetrician-gynecologists. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 32(1):27–34

Lind A, Richter S, Craft C, Shapiro AC (2017) Implementation of routine postpartum depression screening and care initiation across a multispecialty health care organization: an 18-month retrospective analysis. Matern Child Health J 21(6):1234–1239

Lopez LV, Shaikh A, Merson J, Greenberg J, Suckow RF, Kane JM (2017) Accuracy of clinician assessments of medication status in the emergency wetting: a comparison of clinician assessment of antipsychotic usage and plasma level determination. J Clin Psychopharmacol 37(3):310–314

Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G (2000) Maternal depression and parenting behavior: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 20(5):561–592

Mancini F, Carlson C, Albers L (2007) Use of the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale in a collaborative obstetric practice. J Midwifery Women’s Health 52(5):429–434

Marshall M, Lockwood A, Bradley C, Adams C, Joy C, Fenton M (2000) Unpublished rating scales: a major source of bias in randomised controlled trials of treatments for schizophrenia. British J Psychiatry 176(3):249–252

Martins C, Gaffan EA (2000) Effects of early maternal depression on patterns of infant-mother attachment: a meta-analytic investigation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 41(6):737–746

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097

Neal T, Brodsky SL (2016) Forensic psychologists’ perceptions of bias and potential correction strategies in forensic mental health evaluations. Psychol, Public Policy, Law 22(1):58–76

Olson AL, Dietrich AJ, Prazar G, Hurley J, Tuddenham A, Hedberg V, Naspinsky DA (2005) Two approaches to maternal depression screening during well child visits. J Dev Behav Pediatr 26(3):169–176

Osborn MA (2012) Training health visiting support staff to detect likelihood of possible postnatal depression. Community Practitioner 85(4):24–27

Paulson JF, Dauber S, Leiferman JA (2006) Individual and combined effects of postpartum depression in mothers and fathers on parenting behavior. Pediatrics 118(2):659–668

Rowan P, Greisinger A, Brehm B, Smith F, McReynolds E (2012) Outcomes from implementing systematic antepartum depression screening in obstetrics. Arch Women’s Ment Health 15(2):115–120

Schaar GL, Hall M (2013) A nurse-led initiative to improve obstetricians’ screening for postpartum depression. Nurs for Women's Health 17(4):306–316

Schillerstrom JE, Lutz ML, Ferguson DM, Nelson EL, Parker JA (2013) The women’s health objective structured clinical exam: a multidisciplinary collaboration. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 34(4):145–149

Segre LS, Davis WN (2013) Postpartum depression and perinatal mood disorders in the DSM. Postpartum Support Int

Segre LS, Pollack LO, Brock RL, Andrew JR, O'Hara MW (2014) Depression screening on a maternity unit: a mixed-methods evaluation of nurses’ views and implementation strategies. Issues Ment Health Nurs 35(6):444–454

Sheeder J, Kabir K, Stafford B (2009) Screening for postpartum depression at well-child visits: is once enough during the first 6 months of life? Pediatr 123(6):e982–e988

Smith T, Kipnis G (2012) Implementing a perinatal mood and anxiety disorders program. MCN: Am J Matern/Child Nursing 37(2):80–85

Talmi A, Stafford B, Buchholz M (2009) Providing perinatal mental health services in pediatric primary care. Zero to Three (J) 29(5):10–16

Thiam MA, Weis KL (2017) Perinatal mental health and the military family: identifying and treating mood and anxiety disorders. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, New York

Thomason E, Stacks AM, McComish JF (2010) Early intervention and perinatal depression: is there a need for provider training? Early Child Dev Care 180(5):671–683

Tucker P, Crow S, Cuccio A, Schleifer R, Vannatta JB (2004) Helping medical students understand postpartum psychosis through the prism of “the yellow wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Acad Psychiatry 28(3):247–250

Venkatesh KK, Nadel H, Blewett D, Freeman MP, Kaimal AJ, Riley LE (2016) Implementation of universal screening for depression during pregnancy: feasibility and impact on obstetric care. American J Obstet Gynecol 215(4):517–5e1

Wiley CC, Burke GS, Gill PA, Law NE (2004) Pediatricians’ views of postpartum depression: a self-administered survey. Arch Women’s Ment Health 7:231–236

Wisner KL, Logsdon MC, Shanahan BR (2008) Web-based education for postpartum depression: conceptual development and impact. Arch Women’s Ment Health 11(5–6):377–385

Yawn BP, Dietrich AJ, Wollan P, Bertram S, Graham D, Huff J, Kurland M, Madison S, Pace WD, practices TRIPPD (2012) TRIPPD: a practice-based network effectiveness study of postpartum depression screening and management. Ann Fam Med 10(4):320–329

Yonkers KA, Smith DPMV, Lin H, Howell HB, Shao L, Rosenheck RA (2009) Depression screening of perinatal women: an evaluation of the healthy start depression initiative. Psychiatr Serv 60(3):322–328

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 15 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Long, M.M., Cramer, R.J., Jenkins, J. et al. A systematic review of interventions for healthcare professionals to improve screening and referral for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. Arch Womens Ment Health 22, 25–36 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0876-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0876-4