Abstract

This systematic review evaluated the feasibility of implementing universal screening programs for postpartum mood and anxiety disorder (PMAD) among caregivers of infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Four moderate quality post-implementation cohort studies satisfied inclusion criteria (n = 2752 total participants). All studies included mothers; one study included fathers or partners. Screening included measures of depression and post-traumatic stress. Screening rates ranged from 48.5% to 96.2%. The incidence of depression in mothers ranged from 18% to 43.3% and was 9.5% in fathers. Common facilitators included engaging multidisciplinary staff in program development and implementation, partnering with program champions, and incorporating screening into routine clinical practice. Referral to mental health treatment was the most significant barrier. This systematic review suggests that universal PMAD screening in NICUs may be feasible. Further research comparing a wider range of PMAD screening tools and protocols is critical to address these prevalent conditions with significant consequences for parents and infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Of the 3.5 million infants born annually in the US, about 8% are admitted to the NICU [1, 2]. Caregivers (parents and guardians) for these neonates are at high-risk for postpartum mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs) [3, 4]. They often spend months with their newborn in this stressful environment [5], with limited ability to hold and care for their child. The infant’s fragile condition can also interfere with attachment [6, 7]; and in families with more critically ill infants, there is more significant disruption to family dynamics and parenting roles [8,9,10].

This psychological toll puts NICU caregivers at increased risk for mental illness [6, 7, 9, 11,12,13]. The postpartum anxiety rate is 2.5 times higher in mothers with very preterm infants than mothers of term babies [14], and 40% of NICU mothers experience postpartum depression (PPD) [15] compared with up to 20% in the general population [16]. Fathers of preterm or ill neonates also experience higher levels of acute stress disorder, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder than parents of healthy term infants [3, 17, 18].

When symptoms of PMADs are left untreated, caregivers can experience significant difficulties engaging with their infants [19]. This disruption compromises the child’s cognitive and socio-emotional development, resulting in delayed achievement of developmental milestones [20, 21]. To prevent the adverse effects of impaired parent–child bonding, the US Preventive Task Force, American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and American Academy of Pediatrics recommend universal screening for PPD [22,23,24].

Outpatient perinatal depression screening programs have been implemented in many obstetric and pediatric clinics [25,26,27,28,29]. Researchers found these programs to be feasible but challenging to implement. Barriers included lack of provider and staff training [27], poor documentation of depressive symptoms and/or treatment recommendations [29], and liability and risk management [30]. Specifically, pediatricians were unfamiliar with screening tools, and clinic staff were insufficiently trained to provide maternal counseling [25, 27]. In addition, pediatricians had difficulty addressing maternal mental health while prioritizing the child’s health [25]. Although obstetricians are generally more familiar with screening than pediatricians [25], most obstetricians feel inadequately trained to treat maternal depression and anxiety [26]. Despite these obstacles, obstetric and pediatric clinic PMAD screening programs have been associated with higher referral rates, mental health service use, and reduced symptomology [31]. Given the increased risk among NICU caregivers, NICU mental health screening may create opportunities for enhanced support and referrals during the neonates’ hospitalizations and attention to caregivers’ mental health upon discharge.

Prior systematic reviews have evaluated the effectiveness of treatment interventions for addressing caregiver distress in the NICU [32,33,34,35,36,37]. One recent narrative review summarized the clinical effectiveness of outpatient, inpatient, and community perinatal depression screening programs [31]. However, no reviews to date have focused on feasibility of implementing universal PMAD screening programs among caregivers of hospitalized neonates. Perinatal screening programs include “the infrastructure, tools, and procedures to evaluate, diagnose, treat/manage, and follow up [for perinatal depression]” [38]. This is a gap given the high risk of adverse psychological sequalae of these caregivers as described above and the challenges in practical application of screening recommendations. Therefore, the objectives of this study were as follows: (1) examine screening rate as the primary measure of feasibility of universal mental health screening of NICU caregivers, and (2) describe barriers and facilitators for successful universal NICU mental health screening program implementation.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted for studies published before May 2020 via PubMED, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, and Cochrane. Each search contained database-specific vocabulary terms (eg, MESH terms) and keyword terms (eg, mass screening, anxiety disorders, neonatal intensive care, and parent) to identify NICU caregiver PMAD screening programs (see Supplementary Table 1 for full search term queries). The search was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles written in English. References cited by included studies were also screened for inclusion.

Study selection

We included studies meeting the following criteria: (1) described systematic screening for any PMAD, (2) sampled caregivers of neonates admitted to the NICU (hospitalized at birth or within first 28 days of life), (3) used validated depression and PMAD screening tool(s), (4) screened during the neonate’s NICU stay, and (5) described implementation processes, barriers, and facilitators of the screening program. For this review, caregivers were defined as biological mother(s), biological father(s), adoptive parent(s), or other legal guardians of neonates admitted to the NICU for 3 or more days. Included study designs were randomized and non-randomized control trials, cohort studies, case control studies, cross-sectional studies, quasi-experimental studies, and quality improvement studies.

We excluded studies with any of the following sampling criteria: (1) infants admitted to non-NICU inpatient settings, outpatient or non-healthcare setting, (2) infant died in the NICU, (3) non-custodial parent, or (4) selective (not universal) NICU PMAD screening program. Case reports, case series, editorials, opinion articles, and review articles were also excluded.

One author (SM) screened titles and abstracts of identified articles. Full text screening was conducted by two authors (SM and LH). Disagreements were resolved through discussion with the study team.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two authors (SM and LH) independently extracted the following data: (1) study characteristics [(a) study design, (b) duration of study, (c) location (state), and (d) hospital type]; (2) target population for screening; (3) screening instruments utilized; (4) recruitment and implementation strategy, including modality of administration (in person, by paper, by computer, or tablet), staff involved with screening, and distribution protocol (timing to distribute screening tool, linkage with other routine screenings); (5) protocol for positive results; (6) screening rate; (7) prevalence of PMADs among screened caregivers; and (8) barriers and facilitators for screening program implementation. Study authors were contacted to provide additional clarification where needed. Data extraction was reviewed by the team and disagreements resolved by consensus.

Extracted data about program barriers and facilitators were classified into the following categories: patient, provider, administrative, screening, and referral. Data were analyzed between December 26, 2019 and April 30, 2020.

Quality assessment

Two authors (SM and LH) independently assessed the quality of included studies using the modified, validated Downs and Black checklist for randomized and non-randomized studies [39]. This 27-item checklist assesses the quality of reporting (items 1–10), external validity (items 11–13), internal validity (items 14–26) and statistical power (item 27), as used in previous systematic reviews. Study quality was classified as ‘good’ if the total score was 20–27 points, ‘moderate’ if the score was 11–19 points, or ‘poor’ if the score was <11 points. Discrepancies were reconciled through discussion.

Results

Included studies and study characteristics

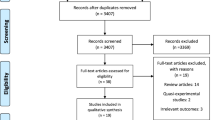

The PRISMA [40] diagram of the study selection process is presented in Fig. 1. Literature search yielded 1954 studies after duplicate records were removed. Of these, 26 studies were considered potentially eligible after title and abstract evaluation for full text review. Only four of the 26 reviewed studies [41,42,43,44], involving 2752 participants, met eligibility criteria. The following are the reasons for excluding 22 records: (1) not evaluating universal screening programs, (2) screening protocol only, (3) outpatient screening, (4) screens caregivers that meet exclusion criteria, (5) ineligible study design, or (6) ineligible publication type. A full list of excluded studies is available in Supplementary Table 2.

All four included studies were post-implementation cohort studies published in peer-reviewed journals. Additional data about screening PPD rates in the Scheans et al. [43] study was derived from a supplemental study report [45] and confirmed through personal communication. Characteristics of included studies are reported in Table 1.

Included studies were graded moderate quality, with ratings ranging from 11 to 15 (mean quality score = 13.5). Interrater agreement was moderate (k = 0.67, 95% CI 0.60, 0.74). Quality assessment scores are summarized in Table 2. Details of scoring with the assessment tool are available in Supplementary Table 3.

Each study was conducted in a different region of the US (West [43], Midwest [41], Northeast [42], and South [44]). Three programs were implemented within the NICU [41, 43], and one was implemented in an obstetrics unit housed within a pediatric hospital, with collaboration between obstetrics and NICU staff [42]. Screening program durations ranged from 2 to 24 months.

Screening protocols

All studies utilized frontline staff to implement screening. Cherry et al. [41], Cole et al. [42], and Vaughn et al. [44] had research coordinators who worked with nursing staff to recruit and screen caregivers. Scheans et al. [43] utilized a lactation consultant, NICU case managers, NICU social workers, and nurses to implement PMAD screening.

Three of the four studies identified key stakeholders and champions during program development. Cole et al. [42] described collaboration between the clinical psychologist and the special delivery unit nurses to develop a screening protocol based on a similar prenatal program screening pregnant mothers. In the year before implementation, a nurse champion was identified to assist the clinical psychologist in staff training, and a clinical research coordinator was recruited to collect data instruments and contact the clinical psychologist for elevated scores. Cherry et al. [41] and Vaughn et al. [44] also worked with a nurse research coordinator.

Prior to screening, three of four studies educated the staff on the impact of PMADs on infants and families [42,43,44]. Cole et al. [42] was the only study that reported providing a formal introduction of their screening and referral protocols and specific staff instruction on how to use screening instruments.

During the implementation phase, studies engaged staff with a range of different roles to distribute the screening instruments, including obstetric charge nurse [42], lactation consultants [43], NICU case managers [43], social works [43], and NICU nurses [43, 44]. Cherry et al. [41] was unique in modifying their screening protocol over the course of the study. When insufficient participants were reached by the research coordinator, nurses were asked to incorporate PMAD screening with routine phenylketonuria screening. When this option created administrative barriers, the research coordinator ultimately placed the instrument in each room with informational brochures for mothers and return instructions.

Screening instruments varied in each study. Cherry et al. [41] and Cole et al. [42] used the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PDSS) to screen for PPD among mothers. In the Cole et al. [42] study, mothers and fathers also completed the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) to evaluate for symptoms of post-traumatic stress. Fathers also completed the Center of Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) to evaluate for symptoms of depression. Scheans et al. [43] and Vaughn et al. [44] screened for PPD among mothers using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Details about screening protocols are reported in Table 3.

Screening and PMAD detection rates

Screening rate was lower in the Cherry et al. study, [41] at 48.5% compared with 89% by Scheans et al. [43], 83.3% by Vaughn et al. [44], and 96.2% by Cole et al. [42] Although Scheans et al. screened at multiple time points, they only reported the overall screening rate. Only Cole et al. [42] screened fathers or partners, reaching 79.5% of these caregivers.

Cherry et al. [41] reported that 35.6% (137/385) of screened mothers had PDSS scores consistent with major PPD (PDSS ≧ 80) and 30.4% (117/385) screened positive for PPD symptoms (PDSS = 60–79) at 14 days postpartum. Cole et al. [42] reported major PPD (PDSS ≧ 80) in 8.8% (64/725) and PPD symptoms (PDSS = 60–79) in 27% (196/725) of screened mothers at 1–3 days postpartum. Scheans et al. [43] reported an overall 18% (67/373) [45] rate of positive screens for mothers screened with the EPDS (EPDS ≧ 10 or suicidal ideation). Vaughn et al. [44] also used the EPDS with same criteria for positive screen, reporting an incidence of 43.3% (13/30) at >30 days postpartum. Depression rates in fathers or partners was significantly lower, at 9.5% (57/602) using the CES-D (CES-D ≧ 21), as reported by Cole et al. [42]

Symptoms of post-traumatic stress were only evaluated by Cole et al. Prevalence was the same for both mothers and fathers/partners at 5.5% [mothers: (40/725), fathers: (33/602) using the IES-R (IES-R ≧ 33)] [42].

Referral protocols

In each study, caregivers who met the prespecified threshold scores that recommended referral were referred to hospital and community services. Cherry et al. [41] and Cole et al. [42] referred mothers with positive screens to inpatient psychologists. Scheans et al. [43] escorted mothers with severe depression scores to the emergency room for immediate intervention. Information about mental health providers in the community via referral brochures were included in all studies. Cherry et al. [41] also faxed screening results to all participants’ primary care providers.

Two of the four studies attempted follow-up with participants beyond the NICU hospitalization [41, 44]. Vaughn et al. [44] followed up within 2 weeks of screening completion and found 4 of 12 contacted mothers were successful in making an appointment. Further details about referral protocols are summarized in Table 3.

Universal PMAD screening and referral implementation facilitators and barriers

Facilitators for screening were identified at the staff and administrative levels. All four studies emphasized that staff engagement was essential for implementation. Inclusion of multidisciplinary staff in protocol development and implementation was beneficial [41,42,43,44]. Having a nurse champion who was familiar with the setting supported streamlining screening into routine care [42]. Hospital administration buy-in [42, 44], partnership with a clinical psychologist [42], staff training [42, 44], and continued support for frontline staff addressed staff concerns and patient safety issues [42]. Modifications in workflow after implementation and subsequent assessment optimized tracking, screening, provider and patient education, and referral [43]. Screening rates improved when linked with routine clinical activities, when staff coverage was increased, and when screening reminders were included in monthly staff meetings, health records, and discharge checklists [41,42,43]. Referrals were more successful when mental health services were available in-house [42], or collaborations with community health centers were established [41]. Collecting release of information forms allowed programs to provide screening results to caregivers’ primary care providers [41].

The studies identified several implementation barriers at the staff and administrative levels. Staff frequently perceived screening as a competing priority, especially in high volume settings [41, 43]. Furthermore, larger units experienced more difficulty training staff and incorporating screening as part of routine care [41]. Administrative issues, including reimbursement and risk management, were also identified. In contrast with the other three programs with sufficient administrative buy-in, Cherry et al. [41] noted insufficient support from administration to harness necessary resources for training nursing staff to administer the PDSS during routine PKU screening.

Numerous barriers for screening and referring caregivers were reported in all studies. Cherry et al. [41] identified language and cultural factors hindering accurate screening. Lack of bilingual staff, as well as the cultural relevance of the screening tool used, were thought to contribute to a lower screening rate among Hispanic participants. Establishing contact with parents for screening proved to be a challenge in the Cherry et al. and Scheans et al. studies [41, 43]. Notably, these two screening programs were conducted in the NICU setting, whereas Cole et al. conducted screening the first day postpartum on the obstetric floor where the caregiver was admitted. Mothers in the NICU were frequently unavailable when staff approached the infant room to screen [41, 43], and screening rates remained low when screening instruments were left at the infant’s bedside [41]. An open layout in the NICU hindered privacy during program enrollment and screening [44]. Once high-risk caregivers were identified, referral to mental health services was especially challenging for those without health insurance [41, 44] or those who did not meet criteria at community health centers [41]. Because mothers had outpatient status while their neonates were admitted, Vaughn et al. [44] were unable to provide hospital-based diagnosis and evaluation for PPD. Implementation barriers and facilitators are summarized in Table 4.

Discussion

Only four studies of the feasibility of implementing universal PMAD screening for NICU caregivers were identified in this systematic review. All programs included in this review were able to reach and screen more than half of NICU caregivers during the evaluation periods, demonstrating promise. The PMAD screening and referral protocols varied with respect to screening tools, procedure for distributing and collecting instruments, and available mental health services, but all utilized frontline staff and a program champion to reach targeted caregivers.

Screening feasibility and incidence of PPD

All four studies were able to engage at least half of their targeted population. However, screening rates are difficult to compare because of variation in protocols. Changes in screening protocols and lack of top leadership support in the Cherry et al. [41] study may have contributed to the low screening rate. Possible explanations for high screening rates by Scheans et al. [43] include screening at four different time points, dedicated time for staff and provider education, and strong hospital administration engagement.

The diversity of screening instruments may also have influenced screening rates. Cherry et al. [41] used the PDSS, which is a 35-item self-report tool, while Scheans et al. [43] and Vaughn et al. [44] used the EPDS, which has 10 items. Although both tools are well-validated in this population [46, 47], the length of the PDSS may be a barrier for some populations, especially non-English speakers. Cole et al. [42] had a similar screening rate to the Scheans et al. [43] and Vaughn et al. [44] studies, but Cole et al. [42] screened in an obstetric rather than NICU setting. Screening in NICU settings, especially in standalone children’s hospitals with limited services and resources for adult care [48], may be more challenging since the mother is not considered the primary focus of care.

The primary PMAD reported is PPD. Although the range of PPD rates in all four studies were relatively consistent with up to 40% reported in previous literature [15], direct comparison is challenging given heterogenous timing for screening, screening rates, and targeted populations. For example, Cole et al. [42] found an incidence of 35.8% at 1–3 days postpartum, compared with 66% at 14 days postpartum by Cherry et al. [41] This is consistent with the findings of a previous systematic review demonstrated increasing point prevalence of PPD in the first 3 months postpartum [16]. In contrast, Scheans et al. [43] had a much lower rate of 18%, perhaps because it reflected the overall rate at multiple time points. Vaughn et al. [44] implemented their program for a shorter time than the other programs, limiting the comparability in PPD incidence. Similarly, the lower response rate may have affected the accuracy of the reported incidence in the study by Cherry et al. [41] Mothers who did not complete screening may have been functioning more poorly or, alternatively, were not experiencing symptoms. Finally, Cole et al. [42] targeted a very specific subpopulation: parents of newborns with prenatally diagnosed birth defects. Taken together, these findings suggest universal PMAD screening programs should include assessment at multiple time points during the NICU stay and that efforts be made to make screening available to hard-to-reach populations.

Implementation facilitators and barriers

Despite the diverse approaches to universal PMAD screening and referral, common programmatic components emerged that are consistent with key facilitators identified in program implementation literature. For example, program champions are essential for sustainability and successful implementation because they can address concerns throughout the implementation stage, act as an organizational buffer, and facilitate networking [49,50,51]. Staff engagement in program development (including training and protocol feedback) establishes buy-in [52]. In addition to promoting staff self-efficacy and bolstering management support [50], monthly feedback allows stakeholders to observe meaningful results and helps sustain interventions [53]. Finally, linkage with existing screening efforts or routine clinical tasks makes this additional screening easier to adopt [52]. Serial workflow modifications into the EMR, such as premade screening feedback forms, automatic referrals, and release of information forms, are examples of built-in sustainability without creating significant barriers to frontline staff [49, 50, 52].

The most significant barrier revealed in this review was referral to mental health services. Barriers included lack of access to in-house psychiatric services, absence of appropriate billing codes for mental health and social service providers, lapsed Medicaid coverage postpartum, and ineligibility for mental health services at community health organizations. These results echo literature emphasizing that a clear referral path is helpful for both providers and families [52]. However, the most powerful predictors of successful screening programs are based on external factors, particularly health policy, insurance reimbursement, and community resources [50]. In fact, one study showed that pediatricians in the Midwest are five times more likely to identify and manage mothers with depression [54]. When the study was published, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois had implemented initiatives to increase awareness, screening, and treatment of PPD [55]. While discussions with payers can support program sustainability beyond grant funding, policy changes that ensure sufficient reimbursement and expansion of mental health services are crucial to bridge the gap between recommendation and clinical practice.

Conversely, community partnerships enhanced screening and referrals [52]. If similar community resources are not available locally, referral barriers can be overcome by integrating mental health services into the routine care offered in the NICU. For example, Cole et al. [42] worked with a clinical psychologist on staff in both the NICU and maternity ward. Access to a clinical psychologist has contributed to the success of screening and referral programs in primary care settings [56,57,58]. A colocated mental health professional would allow for immediate triage for screening positive results and psychosocial support for caregivers [24, 59].

Limitations of studies included in the review

Many universal screening programs in NICUs may have been implemented, but are not yet published. Among the four studies identified in our search, we found varying approaches in evaluation and reporting of screening and moderate study quality, per the Downs and Black criteria. We focused our search on studies addressing barriers and facilitators for universal screening implementation, which may have excluded studies focused on referral issues. Only one included study screened fathers or non-birthing parents, a frequently excluded subpopulation in PMAD screening studies. Furthermore, the unique contexts for each program limits replicability. That said, by identifying common facilitators and barriers, this systematic review gleans successful elements and potential barriers other organizations may face while developing a universal screening program. This focus on implementation facilitators and challenges, rather than program specifics, can help inform future implementation efforts for universal PMAD screening [60].

Notably, the Cole et al. study [42] is unique when compared with the other studies in this review, and limits generalizability. First, they targeted a specific subpopulation of NICU caregivers whose children have malformations. Second, the maternal caregiver was hospitalized in the obstetric setting while their child was in the NICU. That hospitalization provided a clear opportunity for this mother/caregiver to be an identified patient in the hospital electronic health care system, which facilitates access to inpatient psychiatry consultation and services. This model would not be replicable in a standalone children’s hospital that does not provide adult medical care.

In addition, few studies in this review examined issues related to health equity. Low-income and minority populations are the most vulnerable in this already high-risk population [52], and the reach of the screening intervention for this subpopulation was only analyzed by Cherry et al. [41] Understanding characteristics of individuals who accept and refuse services is an important factor in evaluating successful screening implementation and ensures equitable support [50, 52]. A recent review of PPD treatment interventions in the NICU found that low income mothers had lower participation because they were unable to be physically present in the NICU due to inadequate paid family leave, access to childcare, and transportation [61].

Recommendations

Our review of the evidence suggests that universal mental health screening programs for NICU caregivers may be feasible to implement. However, given that only four studies were found in this review, we strongly recommend further research to examine the efficacy of specific components of these programs, such as the benefit of sequential screening in one hospitalization. Three studies employed research assistants to distribute and score the screeners, rather than incorporate these duties to the roles of existing staff. Although the use of research assistants demonstrates feasibility and acceptability of the protocol, further studies will be needed to demonstrate that additional screening duties can be incorporated into existing roles, to identify which roles are best suited for screening, or to determine if additional staff members like community health workers or peer navigators are necessary for implementation.

Future studies must be designed to reach these high-risk NICU caregivers, particularly those with low SES and other underserved populations facing additional barriers to care. Future screening programs should also reach fathers and non-birth mother caregivers to discern the most effective approaches for their engagement in screening and treatment. Research using strong implementation science techniques is critical to understand essential components to optimize universal PMAD screening in neonatal care settings [62]. Additional lessons may be learned from the successful screening and referral programs in outpatient obstetric and pediatric settings [25,26,27,28, 31, 63, 64].

Future research should also focus on cost-effectiveness of implementing universal PMAD screening in NICU settings. Insufficient data regarding resources necessary for program implementation and lack of reimbursement mechanisms are a significant barrier for widespread adoption [52]. Cost-effectiveness and payer data are useful to motivate buy-in from administrative leaders [49].

In summary, this novel systematic review examined the feasibility of implementing universal screening programs for PMADs among NICU caregivers. While only four studies were identified, all programs reached at least half of their target population and identified a high burden of disease. Policy changes that financially support mental health screening programs and services for high-risk caregivers in NICUs can facilitate broader implementation of universal screening recommendations, program sustainability, and improved outcomes for caregivers and neonates alike.

References

Harrison W, Goodman D. Epidemiologic trends in neonatal intensive care, 2007–2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:855–62.

Harrison WN, Wasserman JR, Goodman DC. Regional variation in neonatal intensive care admissions and the relationship to bed supply. J Pediatr. 2018;192:73–9.e4.

Lefkowitz DS, Baxt C, Evans JR. Prevalence and correlates of posttraumatic stress and postpartum depression in parents of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17:230–7.

Singer LT, Salvator A, Guo S, Collin M, Lilien L, Baley J. Maternal psychological distress and parenting stress after the birth of a very low-birth-weight infant. JAMA. 1999;281:799–805.

Edwards EM, Horbar JD. Variation in use by NICU types in the United States. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20180457.

Cleveland LM. Parenting in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Obs Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37:666–91.

Mackay LJ, Benzies KM, Barnard C, Hayden KA. A scoping review of parental experiences caring for their hospitalized medically fragile infants. Acta Paediatr. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14950.

Al Maghaireh DF, Abdullah KL, Chong MC, Chua YP, Al Kawafha MMStress. Anxiety, depression and sleep disturbance among Jordanian mothers and fathers of infants admitted to neonatal intensive care unit: a preliminary study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;36:132–40.

Al Maghaireh DF, Abdullah KL, Chan CM, Piaw CY, Al Kawafha MM. Systematic review of qualitative studies exploring parental experiences in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:2745–56.

Grunberg VA, Geller PA, Bonacquisti A, Patterson CA. NICU infant health severity and family outcomes: a systematic review of assessments and findings in psychosocial research. J Perinatol. 2019;39:156–72.

Roteta AI, Torre MC. Experiences of the parents of extremely premature infants on the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Metas de Enfermería. 2013;16:20–5.

Gondwe KW, Holditch-Davis D. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers of preterm infants. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. 2015;3:8–17.

Wyatt T, Shreffler KM, Ciciolla L. Neonatal intensive care unit admission and maternal postpartum depression. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2019;37:267–76.

Treyvaud K, Lee KJ, Doyle LW, Anderson PJ. Very preterm birth influences parental mental health and family outcomes seven years after birth. J Pediatr. 2014;164:515–21.

Vigod SN, Villegas L, Dennis CL, Ross LE. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low-birth-weight infants: a systematic review. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;117:540–50.

Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr K, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1071–83.

Aftyka A, Rybojad B, Rosa W, Wrobel A, Karakula-Juchnowicz H. Risk factors for the development of post-traumatic stress disorder and coping strategies in mothers and fathers following infant hospitalisation in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:4436–45.

Ionio C, Colombo C, Brazzoduro V, Mascheroni E, Confalonieri E, Castoldi F, et al. Mothers and fathers in NICU: the impact of preterm birth on parental distress. Eur J Psychol. 2016;12:604–21.

Obeidat HM, Bond EA, Callister LC. The parental experience of having an infant in the newborn intensive care unit. J Perinat Educ. 2009;18:23–9.

Hoffman C, Dunn DM, Njoroge WFM. Impact of Postpartum Mental Illness Upon Infant Development. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:100.

McGrath JM, Records K, Rice M. Maternal depression and infant temperament characteristics. Infant Behav Dev. 2008;31:71–80.

Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC, Davidson KW, Ebell M, et al. Screening for depression in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315:380–7.

Committee on Obsetrics and Gynecology. Screening for perinatal depression. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 757. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e208–12.

Earls MF. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1032–9.

Chadha-Hooks PL, Hui Park J, Hilty DM, Seritan AL. Postpartum depression: an original survey of screening practices within a healthcare system. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2010;31:199–205.

Leddy MA, Lawrence H, Schulkin J. Obstetrician-gynecologists and womens mental health: findings of the collaborative ambulatory research network 2005-9. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2011;66:316–23.

Zerden ML, Falkovich A, McClain EK, Verbiest S, Warner DD, Wereszczak JK. et al. Addressing unmet maternal health needs at a pediatric specialty infant care clinic. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27:559–64.

Freeman MP, Wright R, Watchman M, Wahl RA, Sisk DJ, Fraleigh L, et al. Postpartum depression assessments at well-baby visits: screening feasibility, prevalence, and risk factors. J Womens Health. 2005;14:929–35.

Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Kitzman HJ, Wadkins HIM, Conwell Y. Detection of postpartum depressive symptoms by screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics. 2004;113:551–8.

Horwitz SMC, Kelleher KJ, Stein REK, Storfer-Isser A, Youngstrom EA, Park ER, et al. Barriers to the identification and management of psychosocial issues in children and maternal depression. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e208–18.

Reilly N, Kingston D, Loxton D, Talcevska K, Austin MP. A narrative review of studies addressing the clinical effectiveness of perinatal depression screening programs. Women Birth. 2020;33:51–9.

Benzies KM, Magill-Evans JE, Hayden KA, Ballantyne M. Key components of early intervention programs for preterm infants and their parents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:1–15.

Athanasopoulou E, Fox JRE. Effects of kangaroo mother care on maternal mood and interaction patterns between parents and their preterm, low birth weight infants: a systematic review. Infant Ment Health J. 2014;35:245–62.

Sabnis A, Fojo S, Nayak SS, Lopez E, Tarn DM, Zeltzer L. Reducing parental trauma and stress in neonatal intensive care: systematic review and meta-analysis of hospital interventions. J Perinatol. 2019;39:375–86.

Scime VN, Gavarkovs AG, Chaput KH. The effect of skin-to-skin care on postpartum depression among mothers of preterm or low birthweight infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;253:376–84.

Brett J, Staniszewska S, Newburn M, Jones N, Taylor L. A systematic mapping review of effective interventions for communicating with, supporting and providing information to parents of preterm infants. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000023.

Mendelson T, Cluxton-Keller F, Vullo GC, Tandon SD, Noazin S. NICU-based interventions to reduce maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20161870.

Yawn BP, LaRusso EM, Bertram SL, Bobo WV. When screening is policy, how do we make it work? In: Milgrom, J and Gemmill A, editors. Identifying perinatal depression and anxiety: evidence-based practice in screening, pyschosocial assessment, and management. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015. p. 32–50.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377–84.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Cherry AS, Blucker RT, Thornberry TS, Hetherington C, McCaffree MA, Gillaspy SR. Postpartum depression screening in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: program development, implementation, and lessons learned. J Multidiscip Heal. 2016;9:59–67.

Cole JCM, Olkkola M, Zarrin HE, Berger K, Moldenhauer JS. Universal postpartum mental health screening for parents of newborns with prenatally diagnosed birth defects. J Obs Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2018;47:84–93.

Scheans P, Mischel R, Munson M, Bulaevskaya K. Postpartum mood disorders screening in the NICU. Neonatal Netw. 2016;35:240–2.

Vaughn AT, Hooper GL. Postpartum depression screening program in the NICU. Neonatal Netw. 2020;39:75–82.

Lambarth C, Green B. Maternal post-partum mood disorder screening implementation in a neonatal intensive care unit: lessons learned through multnomah project launch background. Portland, OR, 2015. https://www.multnomahesd.org/uploads/1/2/0/2/120251715/ppmd_screening_implementation_issue_brief_2015-10-31.pdf.

Stasik-O’Brien SM, McCabe-Beane JE, Segre LS. Using the EPDS to identify anxiety in mothers of infants on the neonatal intensive care unit. Clin Nurs Res. 2019;28:473–87.

McCabe K, Blucker R, Gillaspy JA Jr, Cherry A, Mignogna M, Roddenberry A, et al. Reliability of the postpartum depression screening scale in the neonatal intensive care unit. Nurs Res. 2012;61:441–5.

Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW. Adult patient visits to children’s hospital emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1268–72.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82:581–629.

Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:228–43.

Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36:24–34.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Depression in parents, parenting, and children: Opportunities to improve identification, treatment, and prevention. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press; 2009. https://doi.org/10.17226/12565.

Hagedorn H, Hogan M, Smith JL, Bowman C, Curran GM, Espadas D, et al. Lessons learned about implementing research evidence into clinical practice: experiences from VA QUERI. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:21–4.

Heneghan AM, Chaudron LH, Storfer-Isser A, Park ER, Kelleher KJ, Stein REK, et al. Factors associated with identification and management of maternal depression by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2007;119:444–54.

Shade M, Miller L, Borst J, English B, Valliere J, Downs K, et al. Statewide innovations to improve services for women with perinatal depression. Nurs Women’s Health. 2011;15:126–36.

Akbari A, Mayhew A, Al-alawi MA, Grimshaw J, Winkens R, Glidewell E, et al. Funders Group Interventions to improve outpatient referrals from primary care to secondary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:1–50.

Maggs-Rapport F, Kinnersley P, Owen P. In-house referral: changing general practitioners’ roles in the referral of patients to secondary care. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:131–6.

Conroy K, Rea C, Kovacikova GI, Sprecher E, Durant H, Reisinger E, et al. Ensuring timely connection to early intervention for young children with developmental delays. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20174017.

Hynan MT, Mounts KO, Vanderbilt DL. Screening parents of high-risk infants for emotional distress: rationale and recommendations. J Perinatol. 2013;33:748–53.

Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implemention science: a synthesis of the literature. Tampa, Florida: National Implementation Research Network; 2005.

Hall EM, Shahidullah JD, Lassen SR. Development of postpartum depression interventions for mothers of premature infants: a call to target low-SES NICU families. J Perinatol. 2020;40:1–9.

Mounts KO. Screening for maternal depression in the Neonatal ICU. Clin Perinatol. 2009;36:137–52.

Moore Simas TA, Brenckle L, Sankaran P, Masters GA, Person S, Weinreb L, et al. The Program in Support of Moms (PRISM): study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial of two active interventions addressing perinatal depression in obstetric settings. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–13.

Tachibana Y, Koizumi N, Akanuma C, Hoshina T, Suzuki A, Asano A, et al. Integrated mental health care in a multidisciplinary maternal and child health service in the community: the findings from the Suzaka trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–11.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to UCSF research librarian, Evans Whitaker, MD, and our research team supervisor, Claudine Catledge, MA.

Funding

LF received support for this work from the University of California, San Francisco, California Preterm Birth Initiative, funded by Marc and Lynne Benioff. LH received support for this work from the National Institute of Nursing Research Biobehavioral Research Training in Symptom Science Grant (T32NR016920). SM, SB, BF, and CM received no funding for this work. Outside of this work, CM is supported by several grants including the National Institutes of Mental Health (R01MH112420), Genentech, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (Grant 2015211), and the California Health Care Foundation. She is a founding member of TIME’S UP Healthcare, but receives no financial compensation from that organization. In 2019, she has received one-time speaking honoraria from Uncommon Bold.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design and methods for the project and provided oversight. SM and LH conducted the searches, quality assessments and data abstraction. SB provided insight into systematic review methodology. BF provided expertise in peripartum mood and anxiety disorders. CM/LF oversaw the entire project, provided supervision to SM/LH, and were actively involved in writing and revising the paper. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings and paper preparation. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murthy, S., Haeusslein, L., Bent, S. et al. Feasibility of universal screening for postpartum mood and anxiety disorders among caregivers of infants hospitalized in NICUs: a systematic review. J Perinatol 41, 1811–1824 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01005-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01005-w

- Springer Nature America, Inc.

This article is cited by

-

Collaborative Recognition of Wellbeing Needs: A Novel Approach to Universal Psychosocial Screening on the Neonatal Unit

Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings (2024)

-

Maternal mental health after infant discharge: a quasi-experimental clinical trial of family integrated care versus family-centered care for preterm infants in U.S. NICUs

BMC Pediatrics (2023)

-

Prevalence and risk factors for postnatal mental health problems in mothers of infants admitted to neonatal care: analysis of two population-based surveys in England

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2023)

-

Parental mental health screening in the NICU: a psychosocial team initiative

Journal of Perinatology (2022)