Abstract

The advantages of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) in breast cancer patients include an enhanced pathological examination of a small number of sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs), which permits more frequent detection of micrometastasis and isolated tumor cells (ITCs). At the same time, however, SLNB raises two new concerns: whether minimal SLN involvement has a significant impact on survival and whether patients with such minimal involvement should undergo further axillary dissections. Two large randomized studies, ACOSOG Z0011 and IBCSG 23-01, have demonstrated that axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) can be avoided for select SLN-positive patients. However, for patients with macrometastasis in SLN or who do not meet the inclusion criteria of the two studies, ALND is still the standard management. On the other hand, previous studies appear to disagree on the prognostic significance of minimal SLN involvement. One of the reasons for this discrepancy is the great variability among pathological examinations for SLN. The OSNA method, which is a fast molecular detection procedure targeting cytokeratin 19 (CK19) mRNA, has the advantage of reproducibility among institutions and the capability to examine a whole lymph node within 30–40 min. This novel method may thus be able to overcome the issue of variability among conventional pathological examinations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Two decades have passed since sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) was first adopted as a treatment for breast cancer. During the first decade, the feasibility and accuracy of sentinel lymph node (SLN) examination for the prediction of axillary nodal status was confirmed and subsequently the methodology was standardized in numerous studies [1–8]. During the next decade, the survival of SLN-negative patients who underwent no further axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) was investigated. Several studies demonstrated that there was no difference in survival among those who did or did not undergo ALND. This clearly established that SLNB alone was a safe and acceptable procedure for SLN-negative patients [9–11].

The advantages of SLNB are as follows: (1) when the SLNs are negative, ALND can be safely avoided, resulting in less morbidity than with ALND and (2) the enhanced pathological examination of a small number (one or a few) of SLNs permits more frequent detection of micrometastasis and ITC. However, SLNB raises new issues; specifically, whether such small metastases have a measurable impact on survival and whether patients with such small metastases should undergo further axillary dissections. This article will address the issue of the prognostic significance of micrometastasis and ITC and the necessity of ALND for patients with such metastatic disease.

What is the impact of micrometastasis in SLN on survival?

Whether minimal SLN metastases have an impact on survival remains controversial even though many small-scale retrospective studies have attempted to address this issue. Some studies have reported observing a significant impact of micrometastasis and ITC on survival, whereas others have not. Hansen et al. [12] reported finding no differences in disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) between patients with micrometastasis and ITC and those without metastatic nodal disease in a prospective analysis of 790 patients with a median follow-up of 72.5 months (Table 1). Gobardhan et al. [13] also reported that DFS and OS were comparable for patients with and without micrometastasis after an adjustment for possible confounding characteristics and for adjuvant systemic treatment. They concluded that survival is not affected by the presence of micrometastasis and ITC in SLN. Similarly, Maaskant-Braat et al. [14]. found no significant difference in overall survival between patients with and without micrometastatic disease, and their results did not change even after adjusting for adjuvant systemic therapy. In sharp contrast to these three studies, the retrospective cohort Micrometastasis and Isolated tumor cells: relevant and robust or rubbish (MIRROR) study found that patients with both micrometastasis and ITC were characterized by a poorer prognosis than those without metastatic nodal disease [15]. This study also demonstrated that adjuvant therapy significantly improved DFS for patients with micrometastasis and ITC. However, the MIRROR trial included patients with favorable tumor characteristics who did not receive adjuvant systemic therapy in accordance with the Dutch guideline at that time. However, the rate of micrometastasis in the MIRROR study was much less than can be expected in daily clinical practice. In addition, the MIRROR trial used DFS as the endpoint. Because the patients with favorable characteristics had a good prognosis, the risk of distant failure was quite low, so that the influence of locoregional recurrence rather than distant recurrence on DFS was relatively high. Another prospective study conducted in Sweden of 3369 patients with a median follow-up of 52 months found that 5-year cause-specific and event-free survival rate was lower for patients with micrometastasis than for node-negative patients. On the other hand, there was no significant difference in survival between node-negative patients and those with isolated tumor cells [16]. Weaver et al. demonstrated in their prospective, multicenter analysis that occult metastases (11.1 % for isolated tumor cells, 4.4 % for micrometastases, 0.4 % for macrometastases) in initially negative SLNs have a small, but significant impact on OS, DFS and distant disease-free interval [17].

Because these studies show substantial discrepancies regarding the prognostic significance of minimal SLN involvement, no definitive conclusions can be drawn. At present, breast cancer patients are treated on the basis of the intrinsic subtype since breast cancers feature quite different prognoses and sensitivity to systemic chemo- and hormonal therapy depending on the intrinsic subtype. To date, however, no studies have been conducted using a subpopulation analysis according to the intrinsic subtypes, even though the impact on survival according to the intrinsic subtypes warrants investigation. Moreover, the great majority of patients enrolled in the above-mentioned studies were estrogen receptor-positive patients whose recurrence often occurs as late as between 5 and 10 years after surgery [18]. However, the mean follow-up periods are usually only approximately 5–6 years, thus longer follow-up studies are required to determine the impact on survival of minimal SLN involvement.

Is ALND necessary for patients with micrometastasis in SLN?

Whether patients with micrometastasis in SLN require further ALND remains controversial. Two very large population studies have addressed this issue. Bilimoria et al. [19] reported the results of their analysis of approximately 100,000 node-positive patients with a median follow-up of 63 months listed in the US National Cancer Data Base (Table 2). The authors found no significant difference in axillary recurrence between those who underwent SLNB alone and those who underwent ALND for micrometastasis in SLN. Consistent with the finding of this analysis, according to data for 6838 patients with microscopic SLN metastases obtained from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, there were no significant differences in ipsilateral regional recurrence for SLNB alone (n = 2240) versus SLNB with completion ALND (n = 4598) [20]. However, in the study by Bilimoria et al., patients with macroscopic SLN metastases showed a tendency to have a lower risk of axillary recurrence for SLNB with ALND compared with SLNB alone. Moreover, in the aforementioned study of the SEER database, patients with macrometastases in SLN had a significantly lower risk of developing ipsilateral regional recurrence after ALND than after SLNB alone. These two studies, although acknowledging certain biases, reflect the experience of daily clinical practice. On the other hand, the Dutch MIRROR cohort study demonstrated that not performing ALND for patients with micrometastases was associated with a higher 5-year regional recurrence and showed that doubling of tumor size, grade 3 and negative hormone receptor status were significantly associated with recurrence [21].

Two large randomized studies were conducted to address the impact of ALND on axillary recurrence in SLN-positive patients. In the prospective multicentric American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 trial, approximately 900 patients with T1-2, N0 breast cancer who underwent breast-conserving surgery (BCS) and SLNB with routine hematoxylin- and eosin-detected metastasis in two or less SLNs were randomized to ALND or no further axillary surgery [22]. All patients received tangential whole breast irradiation. After a median follow-up of 6.3 years, no significant differences in OS and DFS were found between the two groups. It was noted that only 4 (0.9 %) of the 446 SLN-positive patients without ALND showed axillary lymph node recurrence. This result showed no significant differences in a comparison with the 2 (0.5 %) out of 445 SLN-positive patients receiving ALND. In another randomized study, the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) 23-01, patients with one or more micrometastatic SLNs were randomly assigned to either ALND or no ALND [23]. At a median follow-up of 5.0 years, no significant differences in DFS or OS were found between the two groups. Since all patients in the ACOSOG Z0011 trial and approximately 90 % of the patients in the IBCSG 23-01 trial received adjuvant radiotherapy, the local effect of whole breast irradiation on the axillary node basin could not be completely excluded. Moreover, 96 % of the patients in the ACOSOG Z0011 trial and 96 % of those in the IBCSG 23-01 trial were treated with chemotherapy and/or hormonal therapy and such treatment may have also eliminated the minimal SLN involvement. Even after routine ALND, the incidence of local failure including axillary recurrence after a lengthy follow-up is reportedly as high as 2.1 % after ALND, which is similar to that for the ACOSOG Z0011 and IBCSG 23-01 trials. In addition, ALND has been associated with a considerable risk of paresthesia, lymphedema, seroma, sensory change and limitation of shoulder motion [24]. The overall findings reported thus far indicate that ALND can be avoided for T1-2 N0 breast cancer patients with one or two micrometastases and ITC who have been treated with BCS and whole breast irradiation and have received adjuvant chemo- and/or hormonal therapy.

For patients with macrometastasis in SLN, however, only one study (ACOSOG Z0011) has investigated the impact of ALND on axillary recurrence. In addition, none of the patients in the ACOSOG Z0011 trial and approximately 9 % of those in the IBCSG 23-01 trial underwent mastectomy, therefore, it can hardly be said that there is sufficient evidence to avoid ALND for patients with macrometastasis in SLN or for those who have undergone mastectomy. Moreover, we believe that the information on the number of positive nodes obtained by means of ALND remains very important to decide whether there is indication for adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for the chest wall, supraclavicular fossa and internal mammary chain of patients undergoing both BCS and mastectomy [25, 26].

Pathological examination vs. OSNA assay

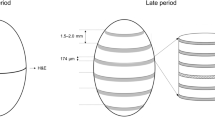

As demonstrated above, current opinions diverge regarding the impact of minimal SLN metastases on survival. One of the reasons for the discrepancy is the great variability among pathological examinations for SLN. The frequency of micrometastasis and ITC varies widely among studies of SLNB for patients with breast cancer. This is mainly because removed SLNs are examined by means of different pathological techniques, including the use of serial sectioning and/or immunohistochemistry (IHC). A number of studies have reevaluated the lymph nodes of breast cancer patients that were thought to be negative following the initial routine histological assessment using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Using various pathological methods, these studies found that 9–32 % of cases previously judged to be node negative contained occult micrometastases and ITC [27]. This implies that in routine pathological examinations, a similar percentage of patients may be misdiagnosed to be node negative. Although the frequency of occult metastases is relatively low, it might have a significant impact on OS and DFS. Thus, Viale et al. [28] described the exhaustive intra-operative frozen section method, in which frozen section (FS) analysis of the entire SLN is performed: 15 or more pairs of 4-μm FSs (stained with both H&E and a rapid IHC method) were analyzed until the entire node is sampled, leaving no tissue for permanent sections. The procedure, which is so laborious and takes 40–50 min, would be impossible to perform on a routine basis for many institutions.

Recently, the one-step nucleic acid amplification (OSNA) assay was developed as a rapid molecular detection procedure targeting cytokeratin 19 (CK19) mRNA which is expressed in breast cancer cells, but not in the normal cells included in the lymph node [29, 30]. A whole assay procedure can be completed within 30-40 min, making it suitable as an intra-operative procedure for detecting SLN metastasis. The advantages of the OSNA assay include good reproducibility among institutions and the capability to examine a whole lymph node within 30–40 min. Several studies have shown that the OSNA assay is more accurate than an intra-operative pathological examination and as accurate as a post-operative examination (Table 3) [30–40]. In these studies, typically four slices are cut from each lymph node, and the two alternating slices are examined using the OSNA assay or histology. Although the sensitivity and specificity of the OSNA assay differ among the reports to some extent, these differences can be mostly explained by differences in the fineness of the histological examination among the studies, i.e., some studies [32–38, 40] adopted serial sectioning and the others did not, [30, 39]; furthermore, the differences can also be explained, at least in part, by the tissue allocation bias. Besides, recent studies have found that the amount of CK19 mRNA copy-number obtained with the OSNA assay is useful for the prediction of non-SLN involvement [41–43].

Another advantage of the OSNA method is to reduce the workload for pathologists. The OSNA assay costs 24,000 yen and the intra-operative frozen section examination costs 19,900 yen for each patient. Although the OSNA assay is slightly more expensive as a test fee, it can be performed by a laboratory technician alone unlike the frozen section examination which requires a technician for sectioning and a pathologist for diagnosis. Thus, the total cost including the test fee and labor expenses is estimated to be similar between the OSNA assay and the frozen section examination.

It is expected that the OSNA method may thus be able to overcome the issue of variability among conventional pathological examinations. Thus, a prospective study of the OSNA method using a large population and a longer follow-up may answer the question whether minimal SLN metastasis in fact affects survival. Although the current OSNA assay adopts the cutoff values of 250 copies and 5000 copies for the diagnosis of micrometastasis and macrometastasis, respectively, it is possible that the optimal cutoff value for recurrence prediction may be different from these cutoff values, and thus efforts are needed to determine the optimal cutoff value for recurrence prediction.

Conclusion

The findings of two large randomized studies, ACOSOG Z0011 and IBCSG 23-01, have demonstrated that ALND can be avoided in T1-2 N0 breast cancer patients with micrometastasis and ITC who have been treated with BCS and whole breast irradiation and who have received adjuvant chemo- and/or hormonal therapy. However, there is currently not enough evidence to omit ALND for patients with macrometastasis or those who do not meet the inclusion criteria of the ACOSOG Z0011 and IBCSG 23-01 trials (e.g., those who have undergone mastectomy). Several studies have shown substantial discrepancies regarding the prognostic significance of minimal SLN involvement. The newly developed OSNA assay may be able to overcome this variability among conventional pathological examinations.

References

Giuliano AE, Kirgan DM, Guenther JM, Morton DL. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1994;220:391–8 (Discussion 398–401).

Shimazu K, Tamaki Y, Taguchi T, Takamura Y, Noguchi S. Comparison between periareolar and peritumoral injection of radiotracer for sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with breast cancer. Surgery. 2002;131:277–86.

Shimazu K, Tamaki Y, Taguchi T, Motomura K, Inaji H, Koyama H, et al. Lymphoscintigraphic visualization of internal mammary nodes with subtumoral injection of radiocolloid in patients with breast cancer. Ann Surg. 2003;237:390–8.

Miyake T, Shimazu K, Ohashi H, Taguchi T, Ueda S, Nakayama T, et al. Indication for sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer when core biopsy shows ductal carcinoma in situ. Am J Surg. 2011;202:59–65.

Shimazu K, Tamaki Y, Taguchi T, Akazawa K, Inoue T, Noguchi S. Sentinel lymph node biopsy using periareolar injection of radiocolloid for patients with neoadjuvant chemotherapy-treated breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:2555–61.

Ogawa Y, Ikeda K, Ogisawa K, Tokunaga S, Fukushima H, Inoue T, et al. Outcome of sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer using dye alone: a single center review with a median follow-up of 5 years. Surg Today. 2014;44(9):1633–7.

Ikeda T. Re-sentinel node biopsy after previous breast and axillary surgery. Surg Today. 2014;44(11):2015–21.

Tanaka S, Sato N, Fujioka H, Takahashi Y, Kimura K, Iwamoto M. Validation of online calculators to predict the non-sentinel lymph node status in sentinel lymph node-positive breast cancer patients. Surg Today. 2013;43(2):163–70.

Imasato M, Shimazu K, Tamaki Y, Taguchi T, Tanji Y, Kim SJ, et al. Long-term follow-up results of breast cancer patients with sentinel lymph node biopsy using periareolar injection. Am J Surg. 2010;199:442–6.

Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Brown AM, Harlow SP, Costantino JP, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:927–33.

Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, Luini A, Zurrida S, Galimberti V, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy as a staging procedure in breast cancer: update of a randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:983–90.

Hansen NM, Grube B, Ye X, Turner RR, Brenner RJ, Sim MS, et al. Impact of micrometastases in the sentinel node of patients with invasive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4679–84.

Gobardhan PD, Elias SG, Madsen EV, van Wely B, van den Wildenberg F, Theunissen EB, et al. Prognostic value of lymph node micrometastases in breast cancer: a multicenter cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1657–64.

Maaskant-Braat AJ, van de Poll-Franse LV, Voogd AC, Coebergh JW, Roumen RM, Nolthenius-Puylaert MC, et al. Sentinel node micrometastases in breast cancer do not affect prognosis: a population-based study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:195–203.

de Boer M, van Deurzen CH, van Dijck JA, Borm GF, van Diest PJ, Adang EM, et al. Micrometastases or isolated tumor cells and the outcome of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:653–63.

Andersson Y, Frisell J, Sylvan M, de Boniface J, Bergkvist L. Breast cancer survival in relation to the metastatic tumor burden in axillary lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2868–73.

Weaver DL, Ashikaga T, Krag DN, Skelly JM, Anderson SJ, Harlow SP, et al. Effect of occult metastases on survival in node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:412–21.

Saphner T, Tormey DC, Gray R. Annual hazard rates of recurrence for breast cancer after primary therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2738–46.

Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Hansen NM, Bethke KP, Rademaker AW, Ko CY, et al. Comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy alone and completion axillary lymph node dissection for node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2946–53.

Yi M, Giordano SH, Meric-Bernstam F, Mittendorf EA, Kuerer HM, Hwang RF, et al. Trends in and outcomes from sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) alone vs. SLNB with axillary lymph node dissection for node-positive breast cancer patients: experience from the SEER database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(Suppl 3):343–51.

Pepels MJ, de Boer M, Bult P, van Dijck JA, van Deurzen CH, Menke-Pluymers MB, et al. Regional recurrence in breast cancer patients with sentinel node micrometastases and isolated tumor cells. Ann Surg. 2012;255:116–21.

Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Blumencranz PW, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305:569–75.

Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, Viale G, Luini A, Veronesi P, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:297–305.

Morcos B, Ahmad FA, Anabtawi I, Sba’ AM, Shabani H, Yaseen R. Development of breast cancer-related lymphedema: is it dependent on the patient, the tumor or the treating physicians? Surg Today. 2014;44(1):100–6.

Budach W, Kammers K, Boelke E, Matuschek C. Adjuvant radiotherapy of regional lymph nodes in breast cancer—a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:267–73.

EBCTCG (Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group), McGale P, Taylor C, Correa C, Cutter D, Duane F, Ewertz M, et al. Effect of radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10-year recurrence and 20-year breast cancer mortality: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22 randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383:2127–35.

Park D, Kåresen R, Naume B, Synnestvedt M, Beraki E, Sauer T. The prognostic impact of occult nodal metastasis in early breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118:57–66.

Viale G, Bosari S, Mazzarol G, Galimberti V, Luini A, Veronesi P, et al. Intraoperative examination of axillary sentinel lymph nodes in breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 1999;85:2433–8.

Tsujimoto M, Nakabayashi K, Yoshidome K, Kaneko T, Iwase T, Akiyama F, et al. One-step nucleic acid amplification for intraoperative detection of lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4807–16.

Tamaki Y, Akiyama F, Iwase T, Kaneko T, Tsuda H, Sato K, et al. Molecular detection of lymph node metastases in breast cancer patients: results of a multicenter trial using the one-step nucleic acid amplification assay. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2879–84.

Tamaki Y, Sato N, Homma K, Takabatake D, Nishimura R, Tsujimoto M, et al. Routine clinical use of the one-step nucleic acid amplification assay for detection of sentinel lymph node metastases in breast cancer patients: results of a multicenter study in Japan. Cancer. 2012;118:3477–83.

Visser M, Jiwa M, Horstman A, Brink AA, Pol RP, van Diest P, et al. Intra-operative rapid diagnostic method based on CK19 mRNA expression for the detection of lymph node metastases in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2562–7.

Schem C, Maass N, Bauerschlag DO, Carstensen MH, Löning T, Roder C, et al. One-step nucleic acid amplification-a molecular method for the detection of lymph node metastases in breast cancer patients; results of the German study group. Virchows Arch. 2009;454:203–10.

Feldman S, Krishnamurthy S, Gillanders W, Gittelman M, Beitsch PD, Young PR, et al. A novel automated assay for the rapid identification of metastatic breast carcinoma in sentinel lymph nodes. Cancer. 2011;117:2599–607.

Khaddage A, Berremila SA, Forest F, Clemenson A, Bouteille C, Seffert P, et al. Implementation of molecular intra-operative assessment of sentinel lymph node in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:585–90.

Snook KL, Layer GT, Jackson PA, de Vries CS, Shousha S, Sinnett HD, et al. Multicentre evaluation of intraoperative molecular analysis of sentinel lymph nodes in breast carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2011;98:527–35.

Le Fre`re-Belda MA, Bats AS, Gillaizeau F, Poulet B, Clough KB, Nos C, et al. Diagnostic performance of one-step nucleic acid amplification for intraoperative sentinel node metastasis detection in breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2011;130:2377–86.

Bernet L, Cano R, Martinez M, Duen˜as B, Matias-Guiu X, Morell L, et al. Diagnosis of the sentinel lymph node in breast cancer: a reproducible molecular method: a multicentric Spanish study. Histopathology. 2011;58:863–9.

Sagara Y, Ohi Y, Matsukata A, Yotsumoto D, Baba S, Tamada S, et al. Clinical application of the one-step nucleic acid amplification method to detect sentinel lymph node metastasis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2013;20:181–6.

Wang YS, Ou-yang T, Wu J, Liu YH, Cao XC, Sun X, et al. Comparative study of one-step nucleic acid amplification assay, frozen section, and touch imprint cytology for intraoperative assessment of breast sentinel lymph node in Chinese patients. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:1989–93.

Osako T, Iwase T, Kimura K, Horii R, Akiyama F. Sentinel node tumour burden quantified based on cytokeratin 19 mRNA copy number predicts non-sentinel node metastases in breast cancer: molecular whole-node analysis of all removed nodes. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1187–95.

Peg V, Espinosa-Bravo M, Vieites B, Vilardell F, Antúnez JR, de Salas MS, et al. Intraoperative molecular analysis of total tumor load in sentinel lymph node: a new predictor of axillary status in early breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139:87–93.

Teramoto A, Shimazu K, Naoi Y, Shimomura A, Shimoda M, Kagara N, et al. One-step nucleic acid amplification assay for intraoperative prediction of non-sentinel lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients with sentinel lymph node metastasis. Breast. 2014;23:579–85.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shimazu, K., Noguchi, S. Clinical significance of breast cancer micrometastasis in the sentinel lymph node. Surg Today 46, 155–160 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-015-1168-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-015-1168-5