Abstract

The treatment of patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) is extremely complex, requiring a comprehensive approach that involves a variety of different healthcare professionals. Several studies have shown that a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach is useful to achieve good clinical outcomes, reducing major and minor amputation and increasing the chance of healing. Despite this, the multidisciplinary approach is not always a recognized treatment strategy. The aim of this meta-analysis was to assess the effects of an MDT approach on major adverse limb events, healing, time-to-heal, all-cause mortality, and other clinical outcomes in patients with active DFUs. The present meta-analysis was performed for the purpose of developing Italian guidelines for the treatment of diabetic foot with the support of the Italian Society of Diabetology (Società Italiana di Diabetologia, SID) and the Italian Association of Clinical Diabetologists (Associazione Medici Diabetologi, AMD). The study was performed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation approach. All randomized clinical trials and observational studies, with a duration of at least 26 weeks, which compared the MDT approach with any other organizational strategy in the management of patients with DFUs were considered. Animal studies were excluded. A search of Medline and Embase databases was performed up until the May 1st, 2023. Patients managed by an MDT were reported to have better outcomes in terms of healing, minor and major amputation, and survival in comparison with those managed using other approaches. No data were found on quality of life, returning-to-walking, and emergency admission. Authors concluded that the MDT may be effective in improving outcomes in patients with DFUs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are a common complication of diabetes mellitus, affecting approximately 19–34% of diabetic patients during throughout their lives [1]. DFUs result from a combination of factors, including peripheral neuropathy, peripheral arterial disease, and foot deformities. These factors can lead to the development of diabetic foot ulcers, which can worsen and lead to tissue necrosis, infection, and ultimately amputation. Patients with a DFU are, in fact, at a high risk for major adverse limb events (MALEs), such as amputation, infection, and death [2, 3].

The treatment of DFUs is therefore complex, requiring a comprehensive approach that addresses all these factors and involves multiple healthcare professionals, such as diabetologists, podiatrists, vascular surgeons, interventional radiologists/cardiologists, infectious disease specialists, wound care nurses, and others.

Several studies have shown that a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach is effective in improving the clinical outcomes for patients with DFUs. Some observational studies (case–control and pre-post study) reported that MDT approaches can reduce the risk of major and minor amputation and increase the rate of healing [4,5,6,7].

There are some reviews and meta-analyses exploring the favorable effects of an MDT approach on patients with DFUs and/or at a high risk of developing a DFU, reporting a significant reduction in major amputation [8,9,10], all-cause mortality [8], but no effects on healing and time-to-heal. Despite these findings, the implementation of the MDT approach is not universal. In some healthcare systems, the care of DFUs is fragmented, with patients being referred to multiple specialists who take care of the patients separately. This can lead to delays in treatment, suboptimal care, and worse outcomes for patients.

Moreover, the above-mentioned meta-analyses in some instances included both patients with an active DFU and at a high risk of developing a DFU (i.e., primary and secondary prevention), with no subgroup analyses, preventing a formal assessment of the MDT in patients with DFU [8,9,10]. In addition, one of these meta-analyses included both the impact of the MDT and that of clinical pathways [11], preventing the evaluation of the MDT effects alone. Finally, the majority of the retrieved meta-analyses cannot include the more recent studies published on this topic [8,9,10].

Accordingly, authors aimed to perform a meta-analysis on randomized and nonrandomized studies assessing the effects of an MDT approach on MALEs, healing, time-to-heal, all-cause mortality, and other clinical outcomes in patients with active DFUs.

The present meta-analysis was performed for the purpose of developing Italian guidelines for the treatment of DFUs. These guidelines, which have been promoted by the Italian Society of Diabetology (Società Italiana di Diabetologia, SID) and the Italian Association of Clinical Diabetologists (Associazione Medici Diabetologi, AMD), are being developed for inclusion in the Italian National Guideline System (INGS), designed as a standard reference for clinical practice in Italy using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [12, 13]. The effects of the MDT on the risk of major adverse limb events (MALEs) and on other secondary outcomes were included among other critical outcomes for the management of DFUs.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in conformity with PRISMA and MOOSE guidelines [14, 15] and following a previously published protocol [16].

Search strategy and selection criteria

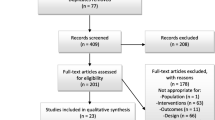

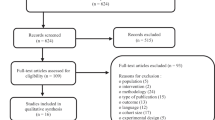

This meta-analysis is part of a wider meta-analysis of studies on diabetic foot syndrome (DFS) conducted for the purpose of developing Italian guidelines on the treatment of diabetic foot syndrome [16]. The present analysis includes all RCTs and observational studies which enrolled patients with DFUs lasting at the least 26 weeks in which the MDT approach was compared with any organizational strategies. Animal studies were excluded, whereas no language or date restriction was imposed. A search of Medline and Embase was performed up until the May 1st, 2023. Detailed information on search strategy is reported in Fig. 1S. Further studies were manually searched in references from retrieved papers.

Selection criteria

To be eligible, a study should meet the following criteria: 1) include adults with type 1 and/or type 2 diabetes and a DFU; 2) include a group of patients managed by an MDT; 3) include a control group (historically controlled pre-post or case–control studies); 4) report the impact of the MDT, which is defined as at least three different clinicians working together, on major and/or minor amputation and/or healing rates, and/or time-to-healing and/or all-cause mortality, and/or “back-to-walking” patients, and/or quality of life, and/or admission to hospital.

We also allowed the inclusion of observational studies because these designs are more frequently used to test this kind of intervention, which cannot be considered a pharmacological treatment. Two independent reviewers (A.S. and C.V.) screened all titles and abstracts of the identified studies for inclusion. Discrepancies were resolved by a third, independent reviewer (M. M.).

Data extraction and collection

Variables of interest were major and/or minor amputation and/or healing rates, and/or time-to-healing and/or all-cause mortality, and/or proportion of “back-to-walking” patients, and/or quality of life, and/or admission to hospital as previously decided (after voting) by the panel of the Italian guidelines for the treatment of DFS.

Data extraction was performed independently by two of the authors (A.S., C.V), and conflicts resolved by a third investigator (M.M.).

The information collected for each trial is summarized in Table 1S.

Titles and abstracts were screened independently, and potentially relevant articles were retrieved in full text. For all published trials, results reported in published papers and supplements were used as the primary source of information. When the required information on protocols or outcomes was not available in the main or secondary publications, an attempt at retrieval was performed consulting the clinicaltrials.gov website. The identification of relevant abstracts and the selection of studies were performed independently. Data extraction and conflict resolution were performed by two investigators (A.S. and C.V.). The risk of bias in RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane recommended tool, which includes seven specific domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other types of bias. The results of these domains were graded as ‘low’ risk of bias, ‘high’ risk of bias, or ‘uncertain’ risk of bias.

Two independent reviewers assessed the methodological quality and risk of bias for each included observational study using a modified Downs and Black checklist for randomized and nonrandomized studies of healthcare interventions [3]. Higher scores indicated higher-quality studies, with a maximum modified score of 25.

Endpoints

The difference between the MDT and control group and pre- and post-MDT in major lower limb amputation was considered the primary endpoint. Secondary endpoints were other MALEs, incidence of all-cause mortality, all-cause hospitalization, healing, time-to-healing, proportion of “back-to-walking” patients, quality of life, and admission to the hospital.

Statistical analyses

Heterogeneity was assessed by the I2 test, whereas Funnel plots were used to detect publication bias for principal endpoints with at least 10 trials.

If data from more than one study on a given outcome were available, a meta-analysis using a random-effects model as the primary analysis was performed. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were either calculated or extracted directly from the publications. Weighted mean differences and 95% CIs were calculated for continuous variables.

Separate analyses were performed for different types of studies (i.e., randomized trials, case–control studies, whenever possible). Sensitivity analyses were performed, whenever possible, if significant heterogeneity was detected, including leave-one out analysis, and/or subgroup analysis for studies with and without: team leader, diabetologist as the team leader, and baseline mean age < and > 65 years.

All analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan), version 5.3 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) methodology [17] was used to assess the quality of the body of retrieved evidence, using GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool. McMaster University, 201,526. Available from gradepro.org).

Results

Retrieved trials

The study flow summary is reported in Fig. 1S of Supporting Information. The Medline and Embase database SEARCH allowed for the identification of 1,514 items (no RCTs); after excluding studies by reading the title, further 93 studies were excluded (Fig. 1S of Supporting Information) after reviewing full text. Of 17 studies [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] which had fulfilled all inclusion criteria, all were observational studies: three were case–control [19, 22, 25], one retrospective [30], and thirteen historically controlled pre-post studies [5, 18, 19, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27,28,29,30, 32, 33]. The three categories of studies were analyzed separately; only one retrospective study was not meta-analyzed since meta-analyses are only possible when at least two studies are present.

The principal characteristics of included studies, which had enrolled a total of 33,787 patients (25,760 managed by an MDT and 8,027 with a traditional approach), are reported in Table 1, 2S of Supporting Information. The mean age, proportion of women, and baseline HbA1c was 63 years, 38, and 9%, respectively.

The quality of studies was heterogeneous (Table 1, 2S of Supporting Information). The Muusuza Bias score was used [10] with a mean bias score of 15.9 (SD 1.4) on a maximum of 25 points. Lack of randomization and blinding detracted from study quality.

Main outcomes

Healing and time of healing

Included observational studies reported very few data on this specific endpoint (one study [23] among case–control studies and three [19, 30, 33] among pre/post studies). These few studies showed an increased chance of wound healing in the interventional group with a low grade of heterogeneity, Fig. 1. Among case–control studies, only one study has been included which demonstrated that the chance of wound healing was increased in patients treated by an MDT, with an OR of 9.81 [95% CI 2.90–33.15], while among the pre-post studies the OR was 2.01 [95% CI 1.16–3.47], Fig. 1.

Only three studies reported healing time [19, 23, 25] with a significant reduction in healing time among patients treated by an MDT Fig. 2.

The MDT patients were reported to have reduced healing time both in case–control studies with an inverse variance (IV) of–46 [− 58.84, − 32.16] and pre-post studies with an IV of—18.01 [− 35.45, − 0.58].

All-cause mortality

Four studies (two case–control [20, 23] and two pre-post [5, 27]) analyzed this item, showing a significant reduction in this endpoint in pre-post studies only [4, 26], Fig. 3.

The pre-post studies showed a reduction in all-cause mortality in patients managed by an MDT with an OR of 0.31 [95% CI 0.18–0.53], Fig. 3.

Minor amputation

Three case–control studies [20, 26, 31] and seven pre-post studies [21, 25, 27,28,29, 32, 33] showed a reduction in minor amputation, which only had a significantly different result in pre-post studies, Fig. 4.

In the pre-post studies, patients treated by an MDT showed a significant reduction in minor amputation with an OR of 0.76 [95% CI 0.58–1.00], Fig. 4.

Major amputation

Three case–control studies [20, 26, 31] and thirteen pre-post studies [18, 19, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27,28,29,30, 32, 33] showed a reduction in major amputation, which only had a significantly different result in pre-post studies, Fig. 5.

The funnel plot suggested publication bias for this outcome, Fig. 2S.

In the pre-post studies, but not in case–control studies, patients managed by an MDT were reported to have a significant reduction in major amputation with an OR of 0.42 [95% CI 0.33–0.53] (Fig. 5).

In addition, when the MDT is led by a team leader, the risk of major amputation seems to be significantly reduced [OR 0.42 (95% CI 0.37–0.47)] in comparison with different organizational strategies, Fig. 3.

Similar results are reported when the MDT is led by a diabetologist [OR 0.42, (95% CI 0.35–0-50)], Fig. 3s.

No difference in terms of major amputation was reported if the MDT is led by a diabetologist or another healthcare professionals team leader, Fig. 4s.

The effectiveness of an MDT approach seems to be similar for reducing major amputation in patients with a baseline age < or > 65 years.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life

No data available.

Back-to-walk

No data available.

Emergency admission

No data available.

For the primary endpoint, (GRADE) methodology [17] was used to assess the quality of the body of retrieved evidence, which was rated as “low.”

Discussion

Although diabetes is dramatically increasing and consequently the long-term complications such as diabetic foot disease, a reduction in amputation and mortality in patients with DFUs have been documented [34]. This is largely related to the continued effort of physicians working in this field, over the last few decades, and can be also attributed to the role of MDTs dedicated to the management of these very complex patients.

This meta-analysis showed that patients managed by an MDT were reported to have a higher chance of healing [18, 31, 32] and reduced healing time [19, 23, 25] in comparison with those not treated by an MDT.

The case–control study reported an OR of 9.81 in terms of an increased chance of healing in the interventional group, while the pre-post studies had an OR of 2.01. Regarding healing time, the case–control studies reported an IV of–46 [− 58.84, − 32.16] and pre-post studies with an IV of—18.01 [− 35.45, − 0.58] in the interventional group.

Most studies showed that the MDT has a huge impact on increasing the survival of patients with DFUs, even if a significant reduction in this endpoint has only been found in two pre-post studies [4, 27].

The pre-post studies showed that the risk of mortality was reduced by 69% [OR 0.31 (95% CI 0.18–0.53)] in patients treated by an MDT in comparison with those treated using different organizational strategy [4, 27].

Positive data have also been found pertaining to both minor and major amputation.

Several studies (all of them pre-post studies) [21, 25, 27,28,29, 32, 33] documented a reduction in minor amputation in patients treated by an MDT when compared to those managed without. These studies showed a risk reduction of 24% [OR 0.76 (95% CI 0.58–1.00)] in minor amputation in the interventional group.

Similar results have been found when major amputation was considered an endpoint, and thirteen pre-post studies showed a significant reduction in major amputation in patients managed by an MDT. The risk of major amputation was reduced by 58% [OR 0.42 (95% CI 0.33–0.53)] in the interventional group when compared to patients treated through different organizational strategies. No significant data were found among case–control studies [20, 26, 31].

Unfortunately, there are no data available regarding the other endpoints identified by including quality of life, back-to-walk, and emergency admission.

In the last few decades, different epidemiological studies have shown a significant trend: a reduction in major amputation in high-income countries, including Italy [35, 36]. This significant improvement may be related to several factors, such as the increase in revascularization procedures for patients with peripheral arterial disease, the use of dedicated offloading, and the adequate and early management of diabetic foot infections. On the other hand, some Italian studies have reported a trend of increased minor amputation in patients with DFUs [37, 38]. However, authors in these studies have concluded that this increase may be a result of using minor amputation as preventative measure in order to reduce major amputation [36]. Even though the increase in minor amputation has been recently documented, the current meta-analysis showed that an MDT approach may reduce both minor and major amputation in comparison with different organizational strategies.

The MDT is usually composed by healthcare professionals having different roles/tasks and specific competences: diabetologist or physician expert in diabetes, vascular surgeons, interventional radiologists/cardiologist, medical specialists in infectious disease, podiatrists, etc. The MDT should operate both in outpatient and inpatient settings, therefore including acute, chronic, and preventive phases.

Close collaboration among healthcare professionals is specifically required in the case of in-hospital patients with diabetic foot problems, as these patients also have a risk of hospital complications [39].

The current meta-analysis showed that having MDT care improves the outcomes (healing, survival, amputation) of patients affected by DFUs. The effectiveness of an MDT approach seems evident even though the team is composed often of different professionals involved in diabetic foot care as reported in Table 1S. These data encourage the role of an MDT in the management of patients with DFUs when compared to different organization strategies where professionals who take care of patients are not coordinated in a shared pathway.

Diabetic foot is a complex disease which requires several healthcare interventions, such as medical, surgical, vascular, and many others. Different healthcare professionals with different expertise are needed for combining their efforts and knowledge to achieve a common goal. A close cooperation for a disease with different clinical aspects can be of help in being more effective, defining the timing of any treatment (i.e., urgency or not of vascular and surgical procedures) and the need to be more or less aggressive by medical or surgical therapy (i.e., to perform extreme revascularization below-the-ankle or recanalize only one specific vessels).

A simple example of what expressed above could be represented by patients with ischemic and infected DFU, and concurrent chronic kidney disease, heart failure, or other co-morbidities suitable for peripheral revascularization and extensive surgical foot intervention. In this case, the vascular team would be unable to perform a lower limb. Revascularization based only on the characteristics of PAD and arterial lesions, but rather the vascular team should work. Together with the surgical team (podiatrist, orthopedic, general surgeon, vascular surgeon, skilled diabetologist), considering the specific location and characteristics of the foot lesion, and the planned foot surgical procedure, in addition, the vascular team and the surgical team should collaborate with the medical team (diabetologists, endocrinologists, internists, specialists in infectious disease) to optimize metabolic control and carefully manage the other cardiovascular risk factors and concomitant co-morbidities (i.e., to prevent possible contrast-induced nephropathy, coagulation disorders, anemia, malnutrition, antibiotic therapy, etc.) to avoid or reduce the risk of peri-procedural complications of peripheral revascularization and foot surgery.

It seems evident that the management of DFS cannot be fragmented, and a single specialist may be unable to manage such as complex disease, particularly in the case of frail patients with severe clinical conditions, such as those with ischemic and infected DFUs requiring hospitalization.

Accordingly, an MDT approach to managing a complex disease like DFS is strongly recommended, along with collective medical, surgical, and vascular aspects.

The MDT may or may not be led by specific team leader. The current meta-analysis documented a significant reduction in major amputation (OR 0.42) when the MDT identified a team leader in comparison with an MDT without (Fig. 2s).

Similar data are reported in the case of the team leader being a diabetologist/endocrinologist in that there was a significant reduction in the rate of major amputation. Nonetheless, very few studies looking at the role of the diabetologist as team leader were found. This resulted in the inability to identify some potential differences in terms of outcomes between an MDT led by a diabetologist/endocrinologist or a different team leader.

In Italy, the time-honored tradition has been having the diabetologist as team leader in the management of diabetic foot disease. The diabetologist, trained and specialized to a high standard, is suitably equipped to manage patients with diabetic foot problems [40]. Diabetologists involved in this field are usually physicians with specific competences, including both clinical and surgical, which allow for the management of all clinical needs and either the partial or full management of surgical needs, from basic wound debridement to advanced surgery, such as demolitive surgery (i.e., necrosectomy, minor amputation, osteotomy, etc.) and reconstructive surgery (implant of dermal substitutes, skin substitutes, cell therapy, etc.) [40].

In different situations and countries, the MDT usually has a similar team, despite the fact that foot surgical procedures are often handled by orthopedics, vascular surgeons, general surgeons, and podiatrists. Nonetheless, regardless of some differences in the team composition, the MDT is effective in improving outcomes of patients affected by diabetic foot problems in comparison with uncoordinated and isolated management.

The MDT should be led by a team leader to improve the outcomes of interest, and when the team leader is a diabetologist, the results appeared to be better in comparison with studies where other team leaders have been considered.

This is mirrored by the fact that in Italy the diabetologist has long been considered the team leader of the MDT because of specialized training which includes surgical skills. Nonetheless, each member with specific skills working in an MDT is essential for an organized strategy and pathway in the treatment of patients with DFUs.

Overall, this meta-analysis included only 17 studies and for some outcomes of interest (i.e., wound healing) only few studies have been considered. This limitation is clearly due to the use of the GRADE method which leads to the exclusion of a significant number of studies, while on the other hand ensuring very careful consideration of specific criteria of selection. Furthermore, the absence of available data on secondary outcomes may easily be related to the method used in this meta-analysis.

Several confounding factors that can influence the outcomes of interest, such as age, co-morbidities, and wound characteristics, were not thoroughly analyzed. In addition, there were incomplete data about the rate of revascularization, the type of revascularization procedure (endovascular and/or surgical), and the technical success. Peripheral revascularization is mandatory in a multidisciplinary approach for patients with an ischemic DFU, and this procedure is often key to achieving successful healing, improving quality of life, reducing amputation and mortality.

Further studies will be useful to evaluate the role of the MDT, particularly those led by a diabetologist, in terms of quality of life, disability and reduction in hospital admission, and readmission.

References

Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA (2017) Diabetic foot ulcers and their recurrence. N Engl J Med 376(24):2367–2375. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1615439. (PMID: 28614678)

Wu H, Yang A, Lau ESH et al (2020) Secular trends in rates of hospitalization for lower extremity amputation and 1 year mortality in people with diabetes in Hong Kong, 2001–2016: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetologia 63(12):2689–2698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05278-2

Morbach S, Furchert H, Gröblinghoff U et al (2012) Long-term prognosis of diabetic foot patients and their limbs: amputation and death over the course of a decade. Diabetes Care 35(10):2021–2027. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0200

Ayada G, Edel Y, Burg A et al (2021) Multidisciplinary team led by internists improves diabetic foot ulceration outcomes a before-after retrospective study. Eur J Intern Med 94:64–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2021.07.007. (Epub 2021 Jul 27 PMID: 34325949)

Rubio JA, Aragón-Sánchez J, Jiménez S et al (2014) Reducing major lower extremity amputations after the introduction of a multidisciplinary team for the diabetic foot. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 13(1):22–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534734614521234. (PMID: 24659624)

Jiménez S, Rubio JA, Álvarez J, Ruiz-Grande F, Medina C (2017) Trends in the incidence of lower limb amputation after implementation of a multidisciplinary diabetic foot unit. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr 64(4):188–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endinu.2017.02.009

Ventoruzzo G, Mazzitelli G, Ruzzi U, Liistro F, Scatena A, Martelli E (2023) Limb salvage and survival in chronic limb-threatening ischemia: the need for a fast-track team-based approach. J Clin Med 12(18):6081. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12186081.PMID:37763021;PMCID:PMC10531516

Buggy A, Moore Z (2017) The impact of the multidisciplinary team in the management of individuals with diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review. J Wound Care 26(6):324–339. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2017.26.6.324

Blanchette V, Brousseau-Foley M, Cloutier L (2020) Effect of contact with podiatry in a team approach context on diabetic foot ulcer and lower extremity amputation: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res 13(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-020-0380-8

Musuuza J, Sutherland BL, Kurter S, Balasubramanian P, Bartels CM, Brennan MB (2020) A systematic review of multidisciplinary teams to reduce major amputations for patients with diabetic foot ulcers. J Vasc Surg 71(4):1433-1446.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2019.08.244

Meza-Torres B, Carinci F, Heiss C, Joy M, de Lusignan S (2021) Health service organisation impact on lower extremity amputations in people with type 2 diabetes with foot ulcers: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Diabetol 58(6):735–747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-020-01662-x

Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA et al (2004) Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 3287454:1490

Kavanagh BP (2009) The GRADE system for rating clinical guidelines. PLoS Med 69:e1000094

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM et al (2021) PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 29(372):n160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160.PMID:33781993;PMCID:PMC8005925

Brooke BS, Schwartz TA, Pawlik TM (2021) MOOSE reporting guidelines for meta-analyses of observational studies. JAMA Surg 156(8):787–788. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0522. (PMID: 33825847)

Monami M, Scatena A, Miranda C et al (2023) Panel of the Italian guidelines for the treatment of diabetic foot syndrome and on behalf of SID and AMD. Development of the Italian clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of diabetic foot syndrome: design and methodological aspects. Acta Diabetol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-023-02150-8

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Santesso N et al (2013) GRADE guidelines: 12. Preparing summary of findings tables-binary outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 66(2):158–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.01.012

Alexandrescu V, Hubermont G, Coessens V et al (2009) Why a multidisciplinary team may represent a key factor for lowering the inferior limb loss rate in diabetic neuro-ischaemic wounds: application in a departmental institution. Acta Chir Belg 109(6):694–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/00015458.2009.11680519

Blanchette V, Hains S, Cloutier L (2019) Establishing a multidisciplinary partnership integrating podiatric care into the Quebec public health-care system to improve diabetic foot outcomes: a retrospective cohort. Foot (Edinb) 38:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foot.2018.10.001

Driver VR, Goodman RA, Fabbi M, French MA, Andersen CA (2010) The impact of a podiatric lead limb preservation team on disease outcomes and risk prediction in the diabetic lower extremity: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 100(4):235–241. https://doi.org/10.7547/1000235

Gibbons GW, Marcaccio EJ, Burgess AM et al (1993) Improved quality of diabetic foot care, 1984 vs 1990: reduced length of stay and costs, insufficient reimbursement. Arch Surg 128(5):576–581. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420170112017

Hsu CR, Chang CC, Chen YT, Lin WN, Chen MY (2015) Organization of wound healing services: The impact on lowering the diabetes foot amputation rate in a ten-year review and the importance of early debridement. Diabetes Res Clin Practice 109(1):77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2015.04.026

Huizing E, Schreve MA, Kortmann W, Bakker JP, de Vries J, Ünlü Ç (2019) The effect of a multidisciplinary outpatient team approach on outcomes in diabetic foot care: a single center study. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 60(6):662–671. https://doi.org/10.23736/s0021-9509.19.11091-9

Kim CH, Moon JS, Chung SM et al (2018) The changes of trends in the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot ulcer over a 10-year period: single center study. Diabetes Metab J 42(4):308–319. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2017.0076

Laakso M, Honkasalo M, Kiiski J et al (2017) Re-organizing inpatient care saves legs in patients with diabetic foot infections. Diabetes Res Clin Practice 125:39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.01.007

Lo ZJ, Chandrasekar S, Yong E et al (2022) Clinical and economic outcomes of a multidisciplinary team approach in a lower extremity amputation prevention programme for diabetic foot ulcer care in an Asian population: a case-control study. Int Wound J 19(4):765–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13672

Martínez-Gómez DA, Moreno-Carrillo MA, Campillo-Soto A, Carrillo-García A, Aguayo-Albasini JL (2014) Reduction in diabetic amputations over 15 years in a defined Spain population. Benefits of a critical pathway approach and multidisciplinary team work. Rev Esp Quimioter 27(3):170–179

Meltzer DD, Pels S, Payne WG et al (2002) Decreasing amputation rates in patients with diabetes mellitus. An outcome study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 92(8):425–428. https://doi.org/10.7547/87507315-92-8-425

Nason GJ, Strapp H, Kiernan C et al (2013) The cost utility of a multi-disciplinary foot protection clinic (MDFPC) in an Irish hospital setting. Ir J Med Sci 182(1):41–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-012-0823-8

Nather A, Siok Bee C, Keng Lin W et al (2010) Value of team approach combined with clinical pathway for diabetic foot problems: a clinical evaluation. Diabet Foot Ankle. https://doi.org/10.3402/dfa.v1i0.5731

Plusch D, Penkala S, Dickson HG, Malone M (2015) Primary care referral to multidisciplinary high risk foot services - too few, too late. J Foot Ankle Res 8:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-015-0120-7

Riaz M, Miyan Z, Waris N et al (2019) Impact of multidisciplinary foot care team on outcome of diabetic foot ulcer in term of lower extremity amputation at a tertiary care unit in Karachi Pakistan. Int Wound J 16(3):768–772. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.13095

Yesil S, Akinci B, Bayraktar F, et al. Reduction of major amputations after starting a multidisciplinary diabetic foot care team: single centre experience from Turkey. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2009;117(7):345–9. (In eng). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0028-1112149.

Bus SA, van Netten JJ, Monteiro-Soares M, Lipsky BA, Schaper NC (2020) Diabetic foot disease: “the times they are a changin.” Diabetes Metab Res Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3249

Carinci F, Uccioli L, Massi Benedetti M, Klazinga NS (2020) An in-depth assessment of diabetes-related lower extremity amputation rates 2000–2013 delivered by twenty-one countries for the data collection 2015 of the organization for economic cooperation and development (OECD). Acta Diabetol 57(3):347–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-019-01423-5. (Epub 2019 Oct 11 PMID: 31605210)

Lazzarini PA, Raspovic KM, Meloni M, van Netten JJ (2023) A new declaration for feet’s sake: Halving the global diabetic foot disease burden from 2% to 1% with next generation care. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3747

Lombardo FL, Maggini M, De Bellis A, Seghieri G, Anichini R (2014) Lower extremity amputations in persons with and without diabetes in Italy: 2001–2010. PLoS ONE 9(1):e86405. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086405.PMID:24489723;PMCID:PMC3904875

Monge L, Gnavi R, Carnà P, Broglio F, Boffano GM, Giorda CB (2020) Incidence of hospitalization and mortality in patients with diabetic foot regardless of amputation: a population study. Acta Diabetol 57(2):221–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-019-01412-8. (Epub 2019 Aug 29 PMID: 31468200)

Meloni M, Andreadi A, Bellizzi E et al (2023) A multidisciplinary team reduces in-hospital clinical complications and mortality in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 9:e3690. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3690

Anichini R, Brocco E, Caravaggi CM et al (2020) SID/AMD diabetic foot study group. Physician experts in diabetes are natural team leaders for managing diabetic patients with foot complications. A position statement from the Italian diabetic foot study group. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 30(2):167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2019.11.009

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Managed by Massimo Porta.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Meloni, M., Giurato, L., Monge, L. et al. Effect of a multidisciplinary team approach in patients with diabetic foot ulcers on major adverse limb events (MALEs): systematic review and meta-analysis for the development of the Italian guidelines for the treatment of diabetic foot syndrome. Acta Diabetol 61, 543–553 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-024-02246-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-024-02246-9