Abstract

Purpose

The Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) is a short and multidimensional scale covering all domains recommended to be included in outcome measures for patients with neck pain. The purpose of the present study was to translate and cross culturally adapt the COMI into Turkish and to test its reliability and validity in patients with neck pain.

Methods

One hundred and six patients with a complaint of chronic neck pain (> 3 months) were enrolled in the present study. Participants completed a questionnaire booklet containing the COMI-neck, Neck Disability Index (NDI), Neck Pain and Disability Scale (NPDS), Short Form-36 (SF-36), and pain Numeric Rating Scale (NRS). The validation of the COMI included the assessment of its construct validity and reliability.

Results

Cronbach’s alpha value of the questionnaire was found to be 0.774 indicating a high internal consistency. Intraclass correlation coefficient values for test–retest reliability were found to be in the range of 0.817–0.986, which indicates a sufficient level of test–retest reliability. Pearson’s correlation coefficient values of the COMI with SF-36, NDI, NPDS, and NRS ranged between 0.417 and 0.700, indicating a good correlation.

Conclusion

Considering the analyses, it was concluded that the Turkish version of the COMI is a valid and reliable scale for chronic neck pain patients.

Graphic abstract

These slides can be retrieved under Electronic Supplementary Material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neck pain is a very common symptom with a 50% incidence rate [1]. Although it is very common, even the most popular treatment methods are insufficient due to the inability to understand the underlying mechanisms. In recent years, it is stated that self-report measurement tools are also important in the measurement of health outcomes in spinal disorders [2]. To evaluate patients with neck pain, several measurement tools are used, such as the Neck Disability Index (NDI) [3], North American Spine Society questionnaire (NASS-cervical) [4], Copenhagen Neck Functional Disability Scale [5], Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire [6], and Neck Pain and Disability Scale (NPDS) [7]. Although the NDI has become popular over time, a scale that is considered to be the gold standard is not yet available. Evaluation of parameters such as pain, symptom-specific function, general well-being, satisfaction, social and work disability in these commonly used measurement tools is considered important [8]. However, the use of a special measuring tool for each parameter takes a long time and makes it difficult to implement [9].

The Core Outcome Measure Index (COMI) is a symptom-specific measurement tool that includes all parameters (pain, function, quality of life, disability) that should be evaluated in patients with low back pain and has the advantages of being short and easy to understand [9,10,11]. COMI is considered as the main patient report outcome scale for the international spine surgery by the Spine Tango—European Spine Association (EUROSPINE) [12]. The COMI-neck scale was developed to complement the COMI-back scale. Psychometric properties of the COMI-neck scale have been tested, and it was found to be valid and reliable in patients with chronic cervical dysfunction [13] and in patients undergoing cervical disk arthroplasty surgery due to cervical degenerative disease [14]. In addition, the COMI-neck scale has been culturally adapted to Italian [15] and Polish [16] and has been found to be valid and reliable. However, there is no Turkish version of the COMI-neck scale.

The aim of the present study was to perform the cultural adaptation of the COMI-neck scale to be used in Turkish-speaking patients with chronic neck pain and to investigate its validity and reliability.

Methods

The process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Turkish COMI-back has already been described in detail [17] and was carried out in accordance with established guidelines [18]. In the scale, for the cervical region, neck pain was used instead of back pain, arm/shoulder pain was used instead of leg/hip pain, and neck problem replaced the back problem. The rest of the wording is exactly the same with the Turkish COMI-back. This study was approved by the local ethics committee of Gazi University (77082166-604.01.02/09). Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

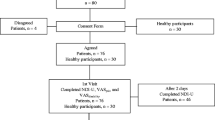

1.1. Patients

One hundred and six patients with neck pain were recruited consecutively from outpatient physiotherapy and rehabilitation clinics. Inclusion criteria were complaints of chronic neck pain (more than 3 months), > 18 years of age, and ability to read and understand Turkish. The exclusion criteria were specific causes of neck pain (e.g., stenosis, deformity, fracture), central and peripheral neurological problems, systemic diseases (e.g., tumors and rheumatologic diseases), and psychiatric disorders. Patients with a recent cerebrovascular event, myocardial infarction, or chronic lung or kidney disease were also excluded from the study. COMI-neck, NDI, NPDS, SF-36, and pain Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) were administered in all patients. To determine test–retest reliability, the COMI-neck was re-administered to 83 patients after 7 days (Fig. 1).

Outcome measures

COMI-neck

The scale is composed of seven items evaluating pain (Item 1a for neck pain and item 1b for arm/shoulder pain), neck-related function (item 2), symptom-specific well-being (item 3), general quality of life (item 4), and disability (item 5 for social aspects and item 6 work-related activities). Except for the questions related to the disability of the patient in the previous 4 weeks, all questions deal with how the patient felt in the previous week. For questions related to pain, a 0–10 graphic rating scale (GRS) is used, and in the remaining questions, a 5-point adjective scale is used. For items 1a–1b, the higher of the two scores is used in order to represent ‘‘pain’’ and for items 5–6, the average is used to represent ‘‘disability.’’ Therefore, the COMI-neck includes five domains, namely pain, function, symptom-specific well-being, quality of life, and disability. To form the COMI summary score, each of the domain scores is transformed to a 0–10 scale and these are then averaged to give a score ranging from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating a worse status [13, 14].

Neck Disability Index (NDI)

The scale is composed of ten dimensions, namely pain intensity, personal care, lifting, reading, headaches, concentration, work, driving, sleeping, and recreation. Each dimension is assessed with 1 item, measured on a 6-point scale from 0 (no pain or functional limitation) to 5 (as much pain as a possible or maximal limitation). Patients are asked to mark the statement that applies to the best. Scores are summed up and this value indicates the disability level of the patient. The total score ranges between 0 and 50. In NDI, a score of 0–4 points indicates no disability, 5–14 points mild disability, 15–24 points moderate disability, 25–34 points severe disability, and over 35 points complete disability [3, 19].

Neck Pain and Disability Scale (NPDS)

This 20-item scale is composed of four sections, namely neck problems, pain intensity, emotion and cognition, and interference with life activities. Each item features a 100 mm-VAS with 6 numerical anchors from 0 to 5 marked at each 20 mm interval. Each item has a score between 0 (no pain or activity limitation) and 5 (as much pain as a possible or maximal limitation). The total score varies between 0 and 100 and a higher score indicates a greater disability [7, 20].

Pain Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)

NRS is an 11-point scale with a score range between 0 (no pain) and 10 (as intense as you can imagine) [21].

Short form health survey (SF-36)

SF-36 is a self-report questionnaire assessing the quality of life. The 36-item questionnaire examines eight dimensions of health, namely physical functioning (PF), social functioning (SF), role physical (RP), role emotional (RE), mental health (MH), vitality (energy) (VT), bodily pain (BP), and general health (GH). The scale provides a rating of 0–100 and a higher score indicates a better health level [22].

Statistical analysis

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 was used for statistical analysis. Test–retest and internal consistency analyses were performed to determine the reliability of the COMI. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (95% confidence interval) was used for test–retest value, and Cronbach’s alpha was used for internal consistency analysis. ICC values 0.80 and above were accepted as a high level of correlation [23]. Cronbach’s alpha values > 0.70 were considered adequate [24]. The higher value that the participant opted for items 1a and 1b, which was about the pain symptoms, was recorded as the value included in the analysis for the pain parameter. To determine the correlation of the disability sub-parameter of the COMI, the mean of items 5 and 6 were taken and recorded as the sub-parameter value.

Floor and ceiling effects were calculated according to the proportion of the scores equivalent the worst status and the best status, respectively. This refers to the proportion of whom, no meaningful deterioration or improvement in their condition could be detected since they are already at the extreme of the range [14]. Because of the different rating of the questionnaires, for the COMI, NDI and NPDS the highest scores represented floor effects (worst status) and the lowest scores, ceiling effects (best status); conversely for the SF-36 scores, the lowest scores represented ceiling effects (best status), and the lowest scores floor effects (worst status). Desired value for floor/ceiling effect is 15–20%, and values more than 70% are considered detrimental [14, 16]. Floor and ceiling effects were determined for all scales, in order to provide data for interpreting the values for the COMI.

Construct validity of the questionnaire was assessed by convergent validity. Convergent validity of the questionnaire was determined using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient method after total scores of the COMI, NDI, NPDS, SF-36, and NRS were obtained. For the Pearson’s correlation coefficient, 0.81–1.00, 0.61–0.80, 0.41–0.60, 0.21–0.40, and 0–0.20 were assumed to be indicating excellent, very good, good, poor, and no correlation, respectively [24,25,26].

Results

In the present study, 66% (n = 70) of the participants were female and 34% (n = 36) were male. While 106 people were included in the internal consistency analysis, 83 people participated in the test–retest study. For the test–retest study, the patients received the questionnaire in 7 days and no treatment was applied during this period. Detailed demographic information of the participants is shown in Table 1.

Cross-cultural adaptation

The stages mentioned in the Materials and Method sections were completed with no complications in terms of translation and cultural adaptation. The Turkish version of the COMI-neck is shown in the ESM Appendix.

Missing data

The questionnaires and descriptive data used for the study were filled by the patients with no intervention. It was observed that four participants did not fill the NDI, NPDS, SF-36 questionnaires and the numeric rating scale used in the validity analysis. For this reason, internal consistency analyzes were carried out with 106 participants and validity analysis was completed with 102 participants.

Floor and ceiling effects

The floor (worst status) and ceiling (best status) effect values of the survey questions are presented in Table 2. The parameters of pain, function, and social and work disability were found to have acceptable (0.9–3.8%) values for floor effect, whereas the symptom-specific well-being sub-parameter was found to have a high (30.2%) floor effect. The ceiling effect of the questionnaire was calculated as acceptable (1.9–18.9%) in pain, function, symptom-specific well-being and quality of life sub-parameters; however, it was found to be high in social and work disability sub-parameters (56.6–73.6%).

When the total scores of the COMI, NDI, NPDS, and NRS values are examined, it is seen that the results have the similar low floor (0–2.9%) and ceiling (0%) effects. However, some of the sub-parameters of the SF-36 questionnaire were found to have a high floor (39.2–46.1%) and ceiling (21.6–35.3%) effects is those with best score and worst score unlike COMI.

Construct validity

For the validity analysis of the COMI, the relationship of the sub-parameters and the total score of the COMI with those of the related sub-parameters and total scores of the NDI, NPDS, NRS, and SF-36 were examined (Table 3). The pain sub-parameter of the COMI and the NRS and SF-36 bodily pain was found to have a correlation value of 0.612 and − 0.604, respectively (very good–good correlation).

The neck function of the COMI and the physical function sub-parameter of the SF-36 showed statistically significant, but weak, correlation (− 0.332). A comparison of the COMI function parameter with the NDI and NPDS total scores, SF-36 bodily pain, and the NRS value revealed good–very good correlation values (0.531–0.636).

The symptom-specific well-being sub-parameter of the COMI showed poor–good correlation with SF-36 general health (− 0.271), NDI (0.364), and NPDS total scores (0.417).

Correlation analysis of the relationship between the quality of life parameter and NDI and NPDS total scores revealed the values of 0.520 and 0.435 (good correlation).

It was observed that the disability sub-parameter had a good correlation with SF-36 RP (− 0.447) sub-parameter, and NDI (0.514) and NPDS (0.414) total scores.

When the total scores were examined, the COMI was found to have a very good correlation with the NDI (0.700) and NPDS (0.651).

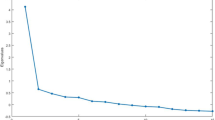

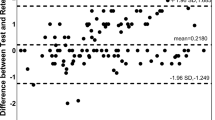

Reproducibility

Internal consistency analysis performed to examine reliability showed a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.774, indicating that the survey has a high internal consistency. ICC values obtained as a result of the test–retest analysis, which is another reliability parameter, were found to be 0.917, 0.913, 0.887, 0.817, and 0.986 for pain, neck function, symptom-specific well-being, quality of life, and disability, respectively (Table 4). The ICC value of the total score of the survey was found as 0.959. According to the test–retest results, it was found that the questionnaire is consistent. Based on the test–retest test results calculated by statistical analysis, it was observed that the time-dependent invariance of the scale was high.

Discussion

In the present study, cultural adaptation of the COMI in a Turkish population with neck pain was performed and its validity and reliability were established. Analyses showed that the Turkish version of the instrument had a high correlation, internal consistency, and test–retest scores.

Translation and cultural adaptation steps were performed following the recommended procedures [17, 18], and no systematic problem was encountered. We found that the Turkish version of the COMI showed great compatibility with the original COMI.

Floor and ceiling effects

In four domains (out of seven domains) of the Turkish COMI, floor and ceiling effects were found to be over normal values (15–20%) [24, 27]. The floor effect, which refers to the worst status value of the symptom-specific well-being parameter, was 30.2%, and the ceiling effect which means best status values of the social disability and disability domains were 56%. However, only the ceiling effect of the work disability value reached a value that may be considered as an adverse effect (73.6%) [28]. Since the disability parameter is based on the average of the work and social disability parameters, it is considered that the high work disability best status may not pose a problem. An analysis of the best–worst status of the COMI summary score showed no floor-ceiling effects (0–1%). Symptom-specific well-being and social and work disability domains of the scale presented a high best–worst status score as is the case for the Italian (21.4–43.7%) [15] and Polish (21.14–59.35%) [16] adaptations. In general, the floor-ceiling effect plays an important role in evaluating the reactivity of health-related quality of life surveys. The measurement of the responsiveness of the COMI showed that the scale is sensitive to variations as much as other neck pain-specific questionnaires [10, 11]. Therefore, it was concluded that the best–worst status scores of the survey did not cause problems in practice.

Construct validity

As the COMI is a multidimensional questionnaire, in order to determine its validity, the correlations of the questionnaire’s domains and total score were evaluated separately with the Turkish versions of NDI, NPDS, SF-36, and NRS. It was observed that other than the symptom-specific well-being domain (− 0.229 to 0.417) of the questionnaire, all parameters, and the total score correlations were found to be high (0.223–0.700). The symptom-specific well-being parameter was also found to be in poor-borderline good correlation in the Italian (− 0.15 to 0.24) [15] and Polish (0.41) [16] adaptations. Similarly, poor correlation values detected for symptom-specific well-being findings were reported for both original version of COMI-neck [14] and COMI-back [11]. Monticone et al. [15] interpreted this result as a unique feature of the questionnaire.

The correlation of the pain parameter, one of the leading complaints of neck pain patients, was found to be sufficient (− 0.604 to 0.616) similar to the Italian (0.45–0.48) [15] and Polish (0.63) [16] adaptations. Even though the correlation between SF-36 was detected fair, the NDI and NPDS total scores, SF-36 bodily pain and NRS values correlation scores were varied between good to very good. The correlation of the function sub-parameter of the COMI (− 0.332 to 0.636) was high, which is in line with the Italian (0.49–0.55) [15] and Polish (0.61) [16] adaptations. Similarly, the correlation of the quality of life sub-parameter (− 0.223 to 0.520) was also high as in the Italian (− 0.23 to 0.44) [15] and Polish (0.58) adaptations [16]. The disability sub-parameter also showed a good correlation (− 0.258 to 0.514) parallel to the Italian (0.45–0.48) [15] and Polish (0.49–0.50) COMI [16]. The total score of the Turkish COMI showed a high correlation (0.622–0.700) as in the Polish COMI (0.65) [16]. These values support the validity of the Turkish COMI.

Reproducibility

Test–retest results were found to be 0.817–0.986 for the sub-parameters and 0.959 for the total score. Compared to the other language adaptations, all sub-domains of the questionnaire were found to be higher: pain (0.917), function (0.913), symptom-specific well-being (0.887), quality of life (0.817), and disability (0.986) [15, 16]. The total score ICC value (0.959) was also found to be higher than those of the other language adaptations (0.878) [15, 16]. These values support the time-dependent invariance of the Turkish COMI.

Based on the internal consistency analysis, Cronbach’s alpha value was found as 0.774; however, the other language adaptations of the COMI did not include any internal consistency analysis results [15, 16]. This ICC value indicates that the Turkish COMI has a high consistency.

Limitations of the study

The present study has some limitations. Responsiveness analysis, which plays an important role in the health-related quality of life questionnaires in determining sensitivity to clinical changes, was not performed in the present study. Responsiveness of the COMI was established in other language adaptations, and it is considered that it should be analyzed also for the Turkish version.

The construct validity of the instrument was not tested in terms of factor analysis. Although the instrument had multiple domains, the Polish version has a unifactorial structure [17]. The analysis of the factorial structure of the instrument in other language adaptations is crucial in determining the method to be used in the analysis of convergent validity.

Conclusion

The present study showed that the Turkish version of the COMI is valid and reliable in a Turkish population with neck pain. It is considered that this easy-to-use, time-saving, and multidimensional COMI questionnaire may be useful in the evaluation and follow-up of patients with neck pain.

References

Fejer R, Kyvik K, Hartvigsen J (2006) The prevalence of neck pain in the world population: a systematic critical review of the literature. Eur Spine J 15:834–848

Bombardier C (2000) Outcome assessments in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disorders: summary and general recommendations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25:3100–3103

Vernon H, Mior S (1991) The Neck Disability Index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manip Physiol Ther 14:409

Stoll T, Huber E, Bachmann S, Baumeler H-R, Mariacher S, Rutz M, Schneider W, Spring H, Aeschlimann A, Stucki G (2004) Validity and sensitivity to change of the NASS Questionnaire for patients with cervical spine disorders. Spine 29:2851–2855

Jordan A, Manniche C, Mosdal C, Hindsberger C (1998) The Copenhagen Neck Functional Disability Scale: a study of reliability and validity. J Manip Physiol Ther 21:520

Leak A, Cooper J, Dyer S, Williams K, Turner-Stokes L, Frank A (1994) The Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire, devised to measure neck pain and disability. Rheumatology 33:469–474

Wheeler AH, Goolkasian P, Baird AC, Darden BV II (1999) Development of the Neck Pain and Disability Scale: item analysis, face, and criterion-related validity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 24(13):1290–1294

Deyo R, Battie M, Beurskens A, Bombardier C, Croft P, Koes B, Malmivaara A, Roland M, Von Korff M, Waddell G (1998) Outcome measures for low back pain research: a proposal for standardized use. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 23:2003–2013

Mannion AF, Porchet F, Kleinstuck FS, Lattig F, Jeszenszky D, Bartanusz V, Dvorak J, Grob D (2009) The quality of spine surgery from the patient’s perspective. Part 1: the Core Outcome Measures Index in clinical practice. Eur Spine J 18(Suppl 3):367–373

Ferrer M, Pellise F, Escudero O, Alvarez L, Pont A, Alonso J, Deyo R (2006) Validation of a minimum outcome core set in the evaluation of patients with back pain. Spine 31:1372–1379

Mannion A, Elfering A, Staerkle R, Junge A, Grob D, Semmer N, Jacobshagen N, Dvorak J, Boos N (2005) Outcome assessment in low back pain: How low can you go? Eur Spine J 14:1014–1026

Melloh M, Staub L, Aghayev E, Zweig T, Barz T, Theis J-C, Chavanne A, Grob D, Aebi M, Roeder C (2008) The international spine registry Spine Tango: status quo and first results. Eur Spine J 17:1201–1209

White P, Lewith G, Prescott P (2004) The core outcomes for neck pain: validation of a new outcome measure. Spine 29:1923–1930

Fankhauser CD, Mutter U, Aghayev E, Mannion AF (2012) Validity and responsiveness of the Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) for the neck. Eur Spine J 21(1):101–114

Monticone M, Baiardi P, Nido N, Righini C, Tomba A, Giovanazzi E (2008) Development of the Italian version of the Neck Pain and Disability Scale, NPDS-I. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33(13):E429–E434

Miekisiak G, Banach M, Kiwic G, Kubaszewski L, Kaczmarczyk J, Sulewski A, Kloc W, Libionka W, Latka D, Kollataj M, Zaluski R (2014) Reliability and validity of the Polish version of the Core Outcome Measures Index for the neck. Eur Spine J 23(4):898–903

Çetin E, Çelik EC, Acaroğlu E, Berk H (2018) Reliability and validity of the cross-culturally adapted Turkish version of the Core Outcome Measures Index for low back pain. Eur Spine J 27(1):93–100

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F et al (2000) Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25:3186–3191

Telci EA, Karaduman A, Yakut Y, Aras B, Simsek IE, Yagli N (2009) The cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity of neck disability index in patients with neck pain: a Turkish version study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 34(16):1725–1735

Bicer A, Yazici A, Camdeviren H, Erdogan C (2004) Assessment of pain and disability in patients with chronic neck pain: reliability and construct validity of the Turkish version of the neck pain and disability scale. Disabil Rehabil 26(16):959–962

Huskinson EC (1974) Measurement of pain. Lancet 2:1127–1131

Pinar R (2005) Reliability and construct validity of the SF-36 in Turkish cancer patients. Qual Life Res 14(1):259–264

Weir JP (2005) Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res 19(1):231–240

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 60:34–42

Gunaydin G, Citaker S, Meray J, Cobanoglu G, Gunaydin OE, Hazar Kanik Z (2016) Reliability, validity, and cross-cultural adaptation of the Turkish version of the Bournemouth Questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 41(21):E1292–E1297

Steiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J (2015) Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. Oxford University Press, Oxford

McHorney CA, Tarlov AR (1995) Individual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res 4:293–307

Hyland M (2003) A brief guide to the selection of quality of life instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:24

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karabicak, G.O., Hazar Kanik, Z., Gunaydin, G. et al. Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Core Outcome Measures Index for the neck pain. Eur Spine J 29, 186–193 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-06169-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-06169-w