Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to translate and cross-culturally adapt the Core Outcome Measures Index for (COMI) into a Simplified Chinese version (COMI-SC) and to evaluate the reliability and validity of COMI-SC in patients with neck pain.

Methods

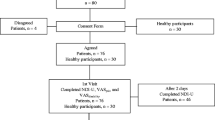

The COMI-neck was translated into Chinese according to established methods. The COMI-neck questionnaire was then completed by 122 patients with a hospital diagnosis of neck pain. Reliability was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Construct validity was assessed by correlating the COMI-neck with the Neck Pain and Disability Scale (NPDS), the Neck Disability Index (NDI), the VAS and the Short Form (36) Health Survey (SF-36). Using confirmatory factor analysis to validate the structural, convergent and discriminant validity of the questionnaire.

Results

The COMI-neck total scores were well distributed, with no floor or ceiling effects. Internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.861). Moderate to substantial correlations were found between COMI-neck and NPDS (r = 0.420/0.416/0.437, P < 0.001), NDI (r = 0.890, P < 0.001), VAS (r = 0.845, P < 0.001), as well as physical function (r = − 0.989, P < 0.001), physical role (r = − 0.597, P < 0.001), bodily pain (r = − 0. 639, P < 0.001), general health (r = − 0.563, P < 0.001), vitality (r = − 0.702, P < 0.001), social functioning (r = − 0.764, P < 0.001), role emotional (r = − 0.675, P < 0.001) and mental health (r = − 0.507, P < 0.001) subscales of the SF-36. An exploratory factor analysis revealed that the 3-factor loading explained 71.558% of the total variance [Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin (KMO) = 0.780, C2 = 502.82, P < 0.001]. CMIN/DF = 1.813, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.966 (> 0.9), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.982 (> 0.9), Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 0.961 (> 0.9), RMSEA = 0.082 (< 0.5) indicating that the model fits well.

Conclusion

COMI-neck was shown to have acceptable reliability and validity in patients with non-specific chronic neck pain and could be recommended for patients in mainland China.

Level of evidence

Diagnostic: individual cross-sectional studies with consistently applied reference standard and blinding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neck pain, which often causes great pain, disability and financial loss, is a very common condition worldwide [1, 2]. It is a very common disease of the musculoskeletal system [3]. The annual incidence of neck pain in the general population is about 15%, with a 1-year prevalence ranging from 4.8 to 79.5% [4, 5]. In addition to a patient's functional status, cervical pain and impaired mobility can negatively impact work activities and quality of life postpartum. Thus, it is critical that clinicians use valid and reliable measures early on to assess patients' disability and outcomes [6, 7].

A patient-based, self-administered Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) questionnaire was developed in order to gain a better understanding of the severity of their illness and to identify more appropriate treatment options [8].

Scoring systems are often used in multicenter studies conducted in different countries and cultures, and there is a growing need for this to increase the statistical power of evidence-based experiments [9, 10]. However, prior to the use of a reliable and valid HRQoL questionnaire in different cultural contexts, in addition to translating the questionnaire, it is necessary to maintain the content validity of the tool in order to avoid cultural bias [11, 12].

In 1998, Deyo et al.[13] recommended a simple and effective tool for assessing outcomes in lumbar spine disease, a set of six core questions known as the Core Outcome Measurement Index (COMI). These questions assessed pain (axial and radiating), functioning, symptom health and disability (social and occupational). The COMI is the European Spine Society's (EUROSPINE) primary patient-reported outcome scale for international spine surgery [14]. The psychometric properties of the COMI-neck Scale, developed to complement the COMI Back Scale, have been validated [15]. COMI has been shown to be reliable and valid in patients with chronic neck pain and those who have undergone disk replacement for degenerative disorders of the neck [15, 16]. Cross-cultural adaptations of the COMI for neck pain have been done in various languages including Turkish [17], Polish [18] and Dutch [19]. However, there is no Chinese version of the COMI-neck scale.

The aim of our study was to cross-culturally translate and adapt COMI into COMI-SC, and assess its reliability and validity in native Chinese with neck pain.

Materials and methods

Patients and data collection

A total of 122 patients were enrolled from seven departments. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients complaining of chronic neck pain (more than 3 months); (2) aged > 18 years; (3) able to read and understand Chinese;(4) patients who signed an informed consent and agreed to participate in this study. Exclusion criteria were patients with spinal tumor, trauma (including fractures) or whiplash, central and peripheral neurological problems, systemic diseases and psychiatric disorders.

In order to test the upper or lower limit effect, validity and reliability of the scale, Terwee et al. [10] determined that the study should include at least 50 patients in order for the sample size to meet the criteria. Informed consent forms were signed by all recruited patients. The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China, approved this study.

Patients were recruited and completed the COMI-SC, Neck Disability Index (NDI), Neck Pain and Disability Scale (NPDS), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) after first providing sex, age, height, weight, marital status, pain duration and education. Two weeks later, the COMI-neck was administered again to 122 patients. Test–retest reliability was determined. (Table 1).

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation questionnaires

We translated and adapted the English version of the COMI in five steps, based on previous guidelines and research and with the consent of the original authors [11, 20]. The steps included forward translation, translation synthesis, backward translation, summarization of the prefinal version and finalization (Table 2). After pretesting the patients, all researchers discussed the issues in the above five steps, the Chinese version of COMI was developed.

Instruments

The core outcome measures index for the neck (COMI-neck)

COMI-neck is a short, self-administered complete scale developed by White et al. [15] in 2004. It can be used to assess neck pain. The COMI-neck consists of 7 items. Five dimensions are assessed: pain, neck-related function, symptom-specific well-being, general quality of life and disability (social and work). Questions 1–5 ask how the patient felt in the previous week, and the last two questions ask about disability in the patient's first four weeks. A 5-point adjective scale was used for the remaining questions except for pain, which used a 0–10 graphical rating scale (GRS). For questions 1 and 2, pain is represented by the higher of the two pain scores (''COMI high pain'') (0–10). The average of the last two items represents the disability dimension. COMI-neck is therefore divided into five dimensions: pain, function, symptom-specific wellness, QoL and disability (social and occupational). The final COMI-neck score is averaged across the five dimensions and the score for each dimension is converted to a 0–10 scale. A higher score indicates a worse patient status [15, 16].

Neck disability index (NDI)

The NDI is a self-administered 10-item scale that measures pain intensity, personal care, weight lifting, reading, headaches, concentration, work, driving, sleep and recreation [21, 22]. Each item is scored from 0 to 5, and an overall score is given for each dimension. The NDI has proven reliable and valid in patients with neck pain.

Neck pain and disability scale (NPDS)

The NPDS is a 20-item questionnaire designed to assess neck pain and disability. It is based on the One Million Visual Analogue Scale [23]. A 10 cm visual analogue scale (VAS) is used for each item. Scores range from 0 (no pain or disability) to 50 (maximum pain or disability). There are 6 vertical lines and 5 grids on each line. The vertical grid is worth half a point, and a mark between the vertical line and the grid increases the score by a quarter. The lowest score is 0 points. The highest score is 100 points.

The short form health survey (SF-36)

SF-36 is a self-reported health questionnaire that assesses patients' overall quality of life [24]. The questionnaire is divided into 8 dimensions, namely physical function (PF), social functioning (SF), physical role (RP), emotional role (RE), mental health (MH), vitality (VT), physical pain (BP) and general health (GH) [25].

Visual analog scale (VAS)

VAS is a visual analogue scale of a patient's perception of pain levels, with a score ranging from 0 (no pain at all) to 10 (worst possible pain) [26].

NDI, NPDS, VAS, and SF-36 have been translated into Simplified Chinese and proven with good reliability and validity [22, 27].

Psychometric assessments and statistical analysis

The questionnaire has both floor and ceiling effects when more than 15% of patients score 0 (lowest) or 10 (highest) [28]. Retest reliability and internal consistency are standard methods for testing COMI reliability [29]. Internal consistency is measured using Cronbach's alpha. Terwee et al. suggest a value of 0.70–0.95 for good internal consistency [10]. To determine test–retest reliability, the intra-group correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from a two-way ANOVA in a random effects model is used. ICC > 0.8 and > 0.9 represent better and worse reliability, respectively. The same patient was asked to complete the COMI-SC questionnaire again two weeks after completing it for the first time. Bland–Altman plots are used to assess intra-object variability and inter-object systematic error [30, 31].

Assessing the content and construct validity of the COMI-SC is also important. Pearson correlations were calculated between the COMI-SC and the NDI, NPDS, SF-36 and VAS. Content validity was assessed by two rehabilitation specialists and three orthopedic surgeons who analyzed the relevance of each item to the patient's condition. Construct validity was assessed by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients between the COMI-SC and the NDI, NPDS, SF-36 and VAS. By comparing the correlation of the data with the calculation, the construct validity of the COMI-SC was assessed. The correlation coefficients were poor ( − 0.2 < r < 0.2), fair (0.2 < r < 0.4 or − 0.4 < r < -0.2), moderate ( − 0.4 < r < − 0.6 or − 0.6 < r < − 0.4), good (0.6 < r < 0.8 or − 0.8 < r < − 0.6) or almost perfect (0.8 < r < 1.0 or − 1.0 < r < − 0.8) [32].

To further test the structural validity of the questionnaire, exploratory factor analyses (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were performed [33].

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) for Windows version 27.0 (IBM Company, Armonk, NY) and IMS SPSS AMOS 24.0 (IBM Company, Armonk, NY).

Results

Cross‑cultural adaption of the COMI-neck

There was no semantic or linguistic ambiguity in the forward and back translation of COMI-neck into Simplified Chinese. All projects were approved by the expert group. It was found that the patients had no ambiguity about the topic after testing the first version of COMI-neck.

Floor and ceiling effects

For each questionnaire, the percentage of floor effect (worst condition) and ceiling effect (best condition) is shown in Table 3. No floor or ceiling effect was observed in any of the individual COMI-neck projects. Nor do the NDI, NPDS and VAS projects show an obvious floor or ceiling effect. There were high floor effects at baseline (81.5% and 87.1%) for some of the individual items of the SF-36 (physical role and emotional role).

Reliability

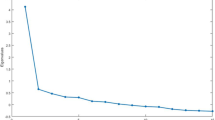

The Cronbach's alpha of the overall COMI-neck was 0.861. This indicates good internal consistency between the items. Table 4 shows the ICC values for the five dimensions of the COMI-neck. There was no significant difference between the retest scores. The Bland–Altman plot (Fig. 1) showed no systematic error. Both results are an indication that the COMI-neck has excellent retest reliability.

The Bland–Altman plot for test–retest agreement of COMI-neck. The differences between scores for COMI-neck from test and retest were plotted against the mean of the test and retest. The line indicates mean difference value of the two sessions and the 95% (mean ± 1.96 standard deviation) limits of agreement

Validity

The content of the questionnaire was judged to be valid enough to assess the impact of neck pain in the enrolled participants by rehabilitation specialists and orthopedic specialists in COMI-neck.

Table 5 shows the correlation coefficients of COMI-neck with NDI, NPDS, VAS and SF-36 subscales, indicating good construct validity. COMI-neck includes 5 dimensions (pain, neck function, symptom-specific well-being, QoL and disability (social and work)) and a summary score. The results showed that the COMI-neck was moderately correlated with the NDI (0.890, P < 0.001). It had a very good correlation with the VAS (0.845, P < 0.001). It correlated moderately with neck dysfunction and disability of the NPDS (0.420, P < 0.001), pain intensity during movement (0.416, P < 0.001), static neck pain intensity (0.437, P < 0.001). And it was also moderately correlated with the physical function of SF-36 ( − 0.989, P < 0.001), role physical ( − 0.597, P < 0.001), bodily pain of SF-36 ( − 0.639, P < 0.001), general health ( − 0.563, P < 0.001), vitality ( − 0.702, P < 0.001), social functioning ( − 0.764, P < 0.001), role emotional ( − 0.675, P < 0.001) and mental health ( − 0.507, P < 0.001). The symptom-specific well-being of COMI-neck was poorly correlated with Neck Dysfunction and Disability of NPDS (0.083, P = 0.366), Pain Intensity with Movement (0.078, P = 0.394) and Static Neck Pain Intensity (0.055, P = 0.545).

To further explore construct validity, we did factor analysis and found that 3-factor loading explained 71.558% of the total variance [Kaiser–Mayer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.780, C2 = 502.82, P < 0.001]. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (df = 21, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

We get the CMIN/DF = 1.813, Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.966 (> 0.9), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.982 (> 0.9), Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 0.961, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.082 (< 0.5), which indicates that the model fits well. The AVE and CR values also reflect the validity (Table 6).

Discussion

We have successfully cross-culturally adapted the COMI for use with patients with neck pain in the Chinese Simplified language. As HRQoL questionnaires play an increasing role in modern healthcare, hospitals, government agencies and research institutions are conducting more outcome studies. Short questionnaires such as COMI-neck are ideal for longitudinal assessment of treatment outcomes [34].

Translation and cross-cultural work are carried out in strict accordance with standardized procedures. There are no systemic problems. We have found that the Simplified Chinese version of the COMI-neck has a high degree of compatibility with the original COMI-neck.

The absence of floor and ceiling effects in the Simplified Chinese version of COMI-neck indicates acceptable internal consistency. This is consistent with previous findings [17, 18]. The physical and emotional dimensions of the SF-36 scale showed a large floor effect, both greater than 80%. This may have been due to the following reasons. Firstly, most of the patients included in the study suffered from mild to moderate neck pain and were treated conservatively in an outpatient setting, and secondly, most of the patients had a chronic course with no acute or recurrent symptoms, so they take this for granted. In life or at work, they therefore take it for granted.

The internal consistency of COMI-neck was nearly good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.861), it is better than the Turkish version [17], but the original version [16], Polish version [18], Italian version [35], Cronbach's alpha is not described in the article. The authors measured ICC values for 5 questions in the original version of COMI-neck. The average ICC value was 0.768 [21]. The ICC value for the Polish version [18] is 0.878. The ICC value for the Turkish version [17] is 0.959 and the ICC value for the Italian version [35] is 0.87. The Simplified Chinese version of COMI-neck has a higher ICC value than the other versions, with the exception of the Turkish version. The original version was retested after 3 days, the Polish version took on average 8 days, and the remaining versions took 7 days. It is explained that the test and retest interval is an important factor that has a significant impact on the ICC value.

We correlated the COMI-neck with the NPDS, NDI, VAS, and SF-36 and found it to be consistent with what we had hypothesized. The higher the scores of COMI-neck, NPDS, NDI and VAS, the worse the patient's function; the lower the score of SF-36 in each dimension, the better the patient's function or quality of life. Therefore, the correlation coefficient between COMI-neck and SF-36 is below 0. The correlation coefficient between the three NPDS dimensions and the symptom-specific well-being dimension in COMI-neck is low. This may be because the COMI-neck questions are about the rest of the patient's life, most patients are optimistic, and the NPDS questions are about current physical condition. In our study, the correlation coefficients between the COMI and the NDI, VAS, and physical subscales (bodily functioning, bodily role, bodily pain, and general health) of the SF-36 were relatively higher. Exploratory factor analysis confirmed COMI-neck's robustness and unidirectional structure.

This study showed the validity of COMI-neck. It discriminated between people with neck pain and other factors that affect daily activities. This finding is in line with the results of the COMI-neck in other languages as well.

The CFI, NFI, CMIN/DF, TLI and RMSEA values indicate a good model fit in the confirmatory factor analysis. The values of AVE and CR on the dimension of disability did not reach the expected values, while the other values indicate a good convergent validity and a good portfolio reliability of the collected questionnaires. This may be due to the small size of the sample used in the model.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the responsiveness of the COMI-neck was not assessed, which could be done in the future. Secondly, although Simplified Chinese is the official language of China, China is a multiethnic country and each ethnic minority has its own language. Therefore, the issue of ethnic minorities should be considered. In addition, the sample size of patients is relatively small and does not represent the general population of mainland China. In addition, this review only examined patients with non-specific neck pain and did not include acute or subacute conditions or patients with specific neck diseases.

Conclusions

This study shows that COMI-neck has been successfully translated and cross-culturally adapted into Simplified Chinese and has sufficient reliability and validity to be used for standard assessment of patients with non-specific chronic neck pain.

References

Safiri S, Kolahi A-A, Hoy D et al (2020) Global, regional, and national burden of neck pain in the general population, 1990–2017: systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m791

Hoy D, March L, Woolf A, Blyth F, Brooks P, Smith E, Vos T, Barendregt J, Blore J, Murray C, Burstein R, Buchbinder R (2014) The global burden of neck pain: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 73:1309–1315. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204431

Ferrari R, Russell AS (2003) Regional musculoskeletal conditions: neck pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 17:57–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1521-6942(02)00097-9

Côté P, Cassidy DJ, Carroll LJ, Kristman V (2004) The annual incidence and course of neck pain in the general population: a population-based cohort study. Pain 112:267–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.004

Hoy DG, Protani M, De R, Buchbinder R (2010) The epidemiology of neck pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 24:783–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2011.01.019

Bombardier C (2000) Outcome assessments in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disorders: summary and general recommendations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 25:3100–3103. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00003

Jackowski D, Guyatt G (2003) A guide to health measurement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000079771.06654.13

Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL (1993) Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med 118:622–629. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009

Freedman KB, Back S, Bernstein J (2001) Sample size and statistical power of randomised, controlled trials in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg Br 83:397–402. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.83b3.10582

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemio. 60:34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D (1993) Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 46:1417–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-n3

Pynsent PB (2001) Choosing an outcome measure. J Bone Joint Surg Br 83:792–794. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.83b6

Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJ, Bombardier C, Croft P, Koes B, Malmivaara A, Roland M, Von Korff M, Waddell G (1998) Outcome measures for low back pain research A proposal for standardized use. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 23:2003–2013. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199809150-00018

Melloh M, Staub L, Aghayev E, Zweig T, Barz T, Theis JC, Chavanne A, Grob D, Aebi M, Roeder C (2008) The international spine registry SPINE TANGO: status quo and first results. Eur Spine J. 17:1201–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-008-0665-2

White P, Lewith G, Prescott P (2004) The core outcomes for neck pain: validation of a new outcome measure. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 29:1923–1930. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000137066.50291.da

Fankhauser CD, Mutter U, Aghayev E, Mannion AF (2012) Validity and responsiveness of the Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) for the neck. Eur Spine J 21:101–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-011-1921-4

Karabicak GO, Hazar Kanik Z, Gunaydin G, Pala OO, Citaker S (2020) Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the core outcome measures index for the neck pain. Eur Spine J. 29:186–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-06169-w

Miekisiak G, Banach M, Kiwic G et al (2014) Reliability and validity of the Polish version of the core outcome measures index for the neck. Eur Spine J 23:898–903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-013-3129-2

Gadjradj PS, Chin-See-Chong TC, Donk D et al (2021) Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the Dutch version of the core outcome measures index for the neck in patients undergoing surgery for degenerative disease of the cervical spine. Neurospine 18:798–805. https://doi.org/10.14245/ns.2142682.341

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB (2000) Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 25:3186–3191. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

Vernon H, Mior S (1991) The neck disability index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 14:409–415

Wu S, Ma C, Mai M, Li G (2010) Translation and validation study of Chinese versions of the neck disability index and the neck pain and disability scale. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 35:1575–1379. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c6ea1b

Wheeler AH, Goolkasian P, Baird AC, Darden 2nd BV (1999) Development of the neck pain and disability scale item analysis, face, and criterion-related validity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 24:1290–1294. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199907010-00004

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30:473–483

Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, Westlake L (1992) Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 305:160–164. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160

Huskisson EC (1974) Measurement of pain. Lancet 2:1127–1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90884-8

Li L, Wang HM, Shen Y (2003) Chinese SF-36 health survey: translation, cultural adaptation, validation, and normalisation. J Epidemiol Community Health 57:259–263. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.4.259

McHorney CA, Tarlov AR (1995) Individual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res 4:293–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF015938823

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159–174

Bland JM, Altman DG (1999) Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 8:135–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/096228029900800204

Bland JM, Altman DG (1986) Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1:307–310

Wei X, Wang Z, Yang C, Wu B, Liu X, Yi H, Chen Z, Wang F, Bai Y, Li J, Zhu X, Li M (2012) Development of a simplified Chinese version of the Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS): cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation. Osteoarth Cart 20:1563–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2012.08.018

Korakakis V, Malliaropoulos N, Baliotis K, Papadopoulou S, Padhiar N, Nauck T, Lohrer H (2015) Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the exercise-induced leg pain questionnaire for English- and Greek-speaking individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 45:485–496. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2015.5428

Hyland ME (2003) A brief guide to the selection of quality of life instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-24

Monticone M, Ferrante S, Maggioni S et al (2014) Reliability, validity and responsiveness of the cross-culturally adapted Italian version of the core outcome measures index (COMI) for the neck. Eur Spine J Off Publ Eur Spine Soci, Eur Spinal Deform Soci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-013-3092-y

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.81972128).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, Y., Cao, S., Qian, D. et al. Simplified Chinese version of the core outcome measures index (COMI) for patients with neck pain: cross-cultural adaptation and validation. Eur Spine J 33, 386–393 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-08088-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-08088-3