Abstract

The prevalence of “vertebral endplate signal changes” (VESC) and its association with low back pain (LBP) varies greatly between studies. This wide range in reported prevalence rates and associations with LBP could be explained by differences in the definitions of VESC, LBP, or study sample. The objectives of this systematic critical review were to investigate the current literature in relation to the prevalence of VESC (including Modic changes) and the association with non-specific low back pain (LBP). The MEDLINE, EMBASE, and SveMED databases were searched for the period 1984 to November 2007. Included were the articles that reported the prevalence of VESC in non-LBP, general, working, and clinical populations. Included were also articles that investigated the association between VESC and LBP. Articles on specific LBP conditions were excluded. A checklist including items related to the research questions and overall quality of the articles was used for data collection and quality assessment. The reported prevalence rates were studied in relation to mean age, gender, study sample, year of publication, country of study, and quality score. To estimate the association between VESC and LBP, 2 × 2 tables were created to calculate the exact odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals. Eighty-two study samples from 77 original articles were identified and included in the analysis. The median of the reported prevalence rates for any type of VESC was 43% in patients with non-specific LBP and/or sciatica and 6% in non-clinical populations. The prevalence was positively associated with age and was negatively associated with the overall quality of the studies. A positive association between VESC and non-specific LBP was found in seven of ten studies from the general, working, and clinical populations with ORs from 2.0 to 19.9. This systematic review shows that VESC is a common MRI-finding in patients with non-specific LBP and is associated with pain. However, it should be noted that VESC may be present in individuals without LBP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is commonly used in the diagnosis of patients with low back pain (LBP) and sciatica [1]. In the search for causes of LBP, vertebral endplate signal changes (VESC) have come into focus. The most commonly used definition of VESC in the literature is from a study of 474 patients with non-specific back pain by Modic et al. [106], who described two types of signal changes: types 1 and 2. From the same study, histological examination performed on type 1 changes in three patients revealed fissured endplates and vascular granulation tissue adjacent to the endplates. In three patients with type 2 changes, disruption of the endplates as well as fatty degeneration of the adjacent bone marrow were observed [106]. Later, type 3 was described as corresponding to sclerosis on radiographs [105].

The prevalence of VESC varies greatly between the studies ranging from less than 1% [82] in adolescents from the Danish general population to 100% [41, 149] in selected patient populations. A large number of studies and narrative reviews have reported on VESC in patient populations with specific LBP (e.g. spondylitis, trauma, tumours and spondyloarthropaties) [55, 57, 64, 144]. VESC has also been investigated in patients with non-specific LBP. In studies of these patients, the association between VESC and LBP has been investigated, with the strength of association from none [96] to strong [154]. The wide range in the reported prevalence rates of VESC and the divergent associations with LBP could be explained by differences in the definitions of VESC and LBP. They could also be explained by differences in the study samples in relation to age, sex, and type of study population (i.e. clinical or non-clinical). Other factors that could also explain the difference in prevalence and association with LBP include year of publication, racial distribution in the study sample, and the overall quality of the study.

To our knowledge, there is no systematic critical review of the literature which addresses the prevalence of VESC and its association with non-specific LBP. Therefore, the overall aim of this study was to systematically review the current literature in relation to “vertebral endplate signal changes” (VESC) in the lumbar spine as seen on magnetic resonance imaging. The specific questions that we wanted to answer were:

-

1.

What is the prevalence of VESC in the absence of specific pathology in relation to:

-

a.

Age?

-

b.

Sex?

-

c.

Study sample?

-

d.

Year of publication?

-

e.

Country of study?

-

f.

Quality of study?

-

2.

Is VESC associated with LBP?

Materials and methods

Search strategy

The MEDLINE, EMBASE, and SveMED databases were searched for the period 1984 to November 2007. Because MRI was not commonly used in a clinical setting before 1984, our search was restricted to the period after 1984. The following terms were searched for as a MeSH term and/or as free text, “MRI”, “vertebral endplate”, and “lumbar spine”. For the purpose of inclusion of relevant articles, we defined VESC as “signal-changes seen on MRI in the vertebral bone, extending from the endplate” [63]. This definition allowed us to describe VESC regardless of aetiology. Also using this definition, articles that described signal changes only present in the bone marrow were excluded.

Definition of quality criteria

The clarity of the articles was assessed on the basis of a set of minimum criteria that the authors considered to be essential for the purpose of this review (Table 1). These items related to (1) the specific research questions (age, sex, year of study, country of study, and study sample) and (2) the overall quality of the article. The items for quality assessment were (a) those that were needed for other researchers to reproduce the study (external validity: population, age, and gender) and (b) those that were needed to ensure quality of the imaging results (internal validity: MR field strength, availability of T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI sequences, definition of VESC, number and professional experience of observers, if observers were blinded to symptoms and other observers’ MRI-readings, and the availability of results from reproducibility study). A checklist that included these items was made and used for data collection (“Appendix”).

Review process

Articles that could be included were original articles written in English, French, German, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, or Russian. Articles to be excluded were (1) reviews, (2) case reports with less than ten patients, (3) comments/letters, (4) animal studies, (5) ex vivo studies, (6) in vitro studies, (7) double publications, and (8) studies that did not really investigate VESC. Furthermore, articles on specific diagnoses or conditions already defined as having an association with LBP were excluded (e.g. spondylodiscitis, ankylosing spondylitis). Studies on individuals with disc herniations with or without sciatica were eligible for review. In case articles had more than one study sample (e.g. case and control groups), these were treated as separate studies for the purpose of the data collection and analysis. The first author inspected all retrieved titles and abstracts and excluded those articles that met the exclusion criteria. After retrieval of the remaining articles in full text, all articles in English were read by two reviewers independently so that each article was read by both the first author and one of the other reviewers. Reference lists of the included articles were searched for additional articles. Articles in French and German were read by one reviewer only. Relevant data from each article were entered in checklists by each reviewer (“Appendix”). Furthermore, articles were screened for data that could be used to estimate an association between VESC and LBP. These articles were independently reviewed by authors 1 and 5 and relevant data were entered in new checklists. For each article, each pair of checklists was checked for consistency by the first author. In case of inconsistencies between two reviewers, the correct information was established through a second consensus reading by authors 1 and 5. Information from the checklists was transferred to a database using EpiData (The EpiData Association, version 3.1, Odense Denmark, 2006).

Data analysis

Variables of interest were transferred to a database in STATA (StataCorp, 2000, Stata Statistical Software: Release 8.2, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) for analyses.

The prevalence rates of VESC were reported in relation to the number of individuals and/or in relation to the number of affected lumbar disc levels. Studies that reported the prevalence in relation to both individuals and levels were included in both analyses. VESC could be defined as type 1, type 2, type 3, mixed types (more than one type situated in the same endplate [88] or within the same person [23]), and any type. The prevalence rates were studied in relation to (1) mean age, (2) gender, (3) study sample (non-LBP, general, working, and clinical populations), (4) year of publication, (5) country of study (Asia, North America, Europe, and other countries), and (6) quality score (0–17). These estimates were analysed visually through graphs and tested for linearity with robust linear regression. For comparison of median values between groups, the Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann–Whitney) test was used. For comparison of mean values between groups, the indicator function for linear regression was used. A P level of 0.05 was considered significant. Two-by-two tables were created, where possible, to estimate the associations between VESC and LBP and presented as exact odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) in relation to age, study sample, and quality of study. In order to calculate exact OR in 2 × 2 tables that included zero in one of the cells, the median unbiased estimation method was used [58]. A positive association was defined as CI limits above 1.

Results

Review process

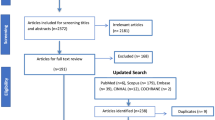

In all, 137 full text articles were reviewed (Fig. 1). Eight were written in German [8, 16, 56, 59, 69, 97, 134, 155], three in French [29, 30, 91], and the remaining articles being in English. There were inter-reader differences in the checklists in 28 cases (11 vs. author 2, 5 vs. author 3, 6 vs. author 4, and 6 vs. author 5). In all these cases, consensus was obtained without difficulties by authors 1 and 5.

A total of 60 papers were excluded after review; 27 as they dealt with specific LBP conditions (Table 2) and 33 for other reasons: one review article [55], four case reports [7, 27, 129, 148], one double publication [90], one of two studies reporting data from the same study sample [80], ten for evaluating signal changes other than those related to the endplate [6, 20, 51, 53, 71, 113, 116, 139, 146, 150], and eight articles because they did not report the exact numbers needed to calculate the prevalence rates of VESC [4, 10, 109, 110, 114, 122, 133, 141]. Finally, eight articles were excluded because the study samples were selected on the basis of the presence of VESC [41, 50, 56, 63, 68, 134, 137, 149]. In 9 of the remaining 77 original articles, a total of 21 study samples were investigated [24, 35, 36, 49, 74, 76, 78, 102, 145]. Seven of these represented specific LBP conditions and were excluded. The 14 study samples, which included patients with non-specific LBP (n = 9) or individuals from the non-clinical population (n = 5), were included. In total 82 study samples from 77 articles were included in the analysis.

What is the prevalence of VESC?

Of the 82 study samples for which the prevalence was investigated, 49 reported prevalence rates of VESC in individuals only, 24 in relation to lumbar levels only, and 9 in relation to both individuals and lumbar levels. The prevalence rate of specific subtypes of VESC was reported in 42 study samples. The median prevalence rates of any type of VESC in relation to individuals and lumbar levels were 36% (n = 58) and 14% (n = 33), respectively (Figs. 2, 3).

Age

Of the 67 study samples for which the mean age was reported, 48 reported the prevalence of VESC in individuals and 28 in relation to lumbar disc levels. A wide spread of prevalence rates was seen regardless of age although with a positive correlation with age. The estimated increase of the prevalence of VESC in individuals was 11% per 10 years (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4) and 6% per 10 years (P < 0.03) for lumbar levels (Fig. 5).

Sex

There was no difference in the prevalence rates of VESC in relation to sex in the 45 study samples that reported the prevalence in individuals or in the 22 study samples that reported the prevalence in relation to levels (data not shown).

Study sample

Of the 58 study samples that reported the prevalence of VESC in individuals, 45 were from clinical populations, two from the general population [81, 82], four from the working population (including top athletes) [13, 17, 36, 88], and the seven study samples of the non-LBP populations were from six studies [24, 31, 38, 62, 78, 153]. The median prevalence of VESC was 6% in study samples of individuals without LBP (n = 7), 12% in the general population (n = 2), 6% in the working population (n = 4), and 43% in study samples from the clinical population (n = 45). Due to the small number of studies that reported prevalence rates from samples of non-clinical populations (non-LBP, general, and working), these three groups were treated as one in the analysis. The median prevalence of VESC in the 13 study samples from the non-clinical population (6%) was significantly less than that from the 45 study samples from clinical population (43%), P < 0.0001 (Fig. 6).

The median prevalence of VESC in relation to lumbar levels was 0% in non-LBP populations (n = 3), 12% in the general population (n = 2), 11% in the working population (n = 4) and 19% in study samples from clinical populations (n = 24). When the study samples from non-clinical populations were combined for the analysis, the prevalence of VESC in lumbar levels was 9% in non-clinical populations (n = 9) and 19% in clinical populations (n = 24), P < 0.02 (Fig. 7).

Year of publication

There was no association between the year of publication and the prevalence of VESC in study samples from which the prevalence rates were reported in relation to individuals (n = 58) or in relation to lumbar levels (n = 33) (data not shown).

Country of study

In relation to the prevalence of VESC in individuals, there was no difference in the mean prevalence between the three geographical regions Europe (n = 33), North America (n = 17), and Asia (n = 8) (data not shown). However, in the 33 study samples in which the prevalence rates were reported in relation to lumbar levels [Europe (n = 22), North America (n = 9), and Asia (n = 2)], the mean prevalence in studies from Europe (19%) was higher than that in studies from Asia (9%, P < 0.05), but not higher than that in studies from North America (15%).

Quality of study

The mean quality score (0–17) was 11.7 and only two [35, 81] (3%) of the 77 original articles included in the review met all quality criteria (Table 3). The criteria that most articles did not meet were related to the description of the MRI evaluation and the procedures concerning reproducibility.

For the 58 articles that reported the prevalence of VESC in individuals, there was a negative linear association between the prevalence and the quality score (P < 0.001) (Fig. 8). There was no association between the prevalence of VESC and the quality score in relation to lumbar levels (data not shown).

Is VESC associated with LBP?

There were ten studies from which data could be extracted to estimate the association between VESC and LBP (Table 4). A positive association could be estimated in three of the five studies that used provocative discography as the LBP outcome and in four of the five studies that used self-reported LBP as an outcome. The odds ratios for these seven studies ranged from 2.0 to 19.9. There was no difference in the association between LBP and the type of VESC in five studies of the ten studies where data were available to estimate an association [3, 18, 84, 126, 154].

Due to the small number of studies, it was not meaningful to investigate if there were differences in the association between VESC and LBP in relation to different study samples, quality of study, or age groups.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic critical literature review on VESC in relation to its prevalence and association with non-specific LBP.

Results from this review document that VESC is a common MRI-finding in patients with non-specific LBP with a median prevalence of 43% and it is less common in non-clinical populations with a median prevalence of 6%. Also, it is documented that the prevalence increases with age and it is more common in Europe than in non-European countries.

In this review, we found a positive association between VESC and LBP in the majority of studies reporting on this subject. According to a recent systematic review on the diagnostic accuracy of tests for low back pain [54], the presence of VESC increases the likelihood of having LBP during provocative discography. Our review that also included studies on self-reported LBP came to the same conclusion. The ORs for the studies that reported a statistically significant positive association ranged from 2.0 to 19.9, which is a relatively strong association. However, the confidence limits for these estimations were wide for the studies that used discography to provoke pain. Although the number of studies is small, it is important to note that a positive association between VESC and LBP has not only been found in the majority of studies of patients with LBP from different countries, but also in the general [81] and working [88, 126] populations. In other words, there is a considerable consistency in this association.

If VESC is a condition that causes LBP, it seems likely that the prevalence would be the highest in study samples of patients with LBP, lower in study samples from the general and working population and lowest in individuals without LBP. The present review did not identify such a linear pattern, because of the small number of study samples from the non-clinical populations (i.e. non-LBP, general, and working populations). However, when the non-clinical populations were combined in one group, the prevalence of VESC was found to be more than seven times higher among patients with non-specific LBP than in individuals from the non-clinical populations.

As expected, the prevalence of VESC increases with age [87, 106]. This seems plausible as VESC is correlated to disc degeneration [80, 106], which in turn is correlated to age [15].

A statistically higher prevalence of VESC in studies from Europe as compared to studies from Asia was only found for lumbar levels based on 22 studies from Europe and only 2 studies from Asia. Therefore, the difference in the prevalence between the two geographical regions could be explained by an increased awareness of VESC in Europe (i.e. publication bias). Another explanation could be that VESC is more prevalent in Europe, perhaps on the basis of specific genes that are associated with (1) an increased risk of tissue injury, (2) and increased response to injury, or (3) a decreased ability to heal injured tissue. In support of this theory, there are different prevalence rates of genes associated with disc degeneration for individuals from Northern Europe as compared to Asian populations [5, 67, 112, 128, 147]. Also, a recent study suggests that VESC may be related to increased response to injury, as a combination of specific genes (IL1A and MMP-3) increased the odds of having type 2 changes by eight times [73].

There was a negative association between the prevalence of VESC and the quality score. The overall quality of the study is a proxy for both the technical and analytical aspects of the study process. For example, studies that do not have a systematic and reproducible evaluation protocol are more likely to have misclassification and thus more biased estimates of the prevalence.

The reasons why VESC may be painful are not known. The lumbar vertebral endplate contains immunoreactive nerves, as shown in studies of sheep and humans [21, 40], and it has been reported that an increased number of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) immunoreactive nerve cells and fibres are present in endplates that have VESC, especially in type 1 changes [111]. Therefore, the pain may originate from damaged endplates in patients with VESC. Another possibility is that VESC is a proxy for discogenic pain, as VESC is most often seen in relation to disc degeneration [3, 80, 87, 106] and immunoreactive nerves have also been shown to be present in degenerative discs [43]. Interestingly though, the association between VESC and LBP seems to be stronger than that between mere disc degeneration and LBP [80].

The causes of VESC are unknown. Because VESC is present in several specific LBP conditions, there may be several causes. In patients with non-specific LBP, one theory is that disc injury leads to increased loading and shear forces on the endplates, which can lead to fissures of the endplate [2]. In support of this theory, a prospective study of 166 patients with sciatica treated non-surgically, reported a threefold increase of type 1 changes over a period of 14 months [3]. Further evidence in favour of this theory are the results from studies on baboons and rats, where it has been reported that injury to the disc induces changes in the adjacent vertebrae with subsequent bone marrow depletion and degeneration and regeneration of the bone [101, 108, 143].

Systematic literature reviews offer an excellent opportunity to gain an overview of a confusing topic. However, they also have some limitations that need to be addressed. In this review, we sometimes included more than one study sample from the same original study in the analyses [24, 49, 74, 76]. If the original studies are biased in one way or other, this will also be the case for the individual study samples. Thus, the bias of one study will have an unsuitable effect on several study samples.

Another problem is whether the studies submitted to scrutiny had been designed to answer the research questions of the review. In our case, this was true for the prevalence of VESC. Also, the correlation with age had to be based on the mean prevalence for each study rather than for specific age groups. Furthermore, a small number of relevant studies make interpretation of data difficult, as in this review, where there were a limited number of studies testing the association with LBP. Finally, there is always the danger of publication bias, particular if the subject is new and perhaps controversial, as is the case with VESC.

The strengths of this review are that the studies included are homogeneous in relation to the definition of VESC, and that VESC is an MRI-finding easy to evaluate and is supported by four studies that have reported the inter-observer reproducibility of a detailed evaluation of VESC with Kappa values ranging from 0.64 to 0.91 [31, 63, 68, 72, 87]. Also, our review was performed by five reviewers and all articles, except those written in German or French (n = 11), were evaluated independently by at least two of the reviewers, thus limiting the risk of bias in the evaluation. Finally, the search strategy for this review included articles written in European languages other than English and was made to cover articles that described either the prevalence of VESC or its association with LBP. This broad search strategy would have minimised the risk of missing relevant articles. The strength in relation to the estimation of an association between VESC and LBP is that we used both discography and self-reported LBP as outcomes. This did not only increase the number of studies included in the analysis, but also gave us the opportunity to investigate the association with LBP in non-clinical populations.

Consequences

Our results indicate that clinicians should be aware that patients with “non-specific” LBP may well have a clinically relevant diagnosis. Although we know very little about the treatment and prognosis of VESC, it is possible that giving the patients a likely explanation for their pain could relieve them from anxiety and stress.

In order to improve our knowledge, it is important that researchers report findings in relation to age, sex, ethnicity, and type of LBP. It is relevant to proceed to observational studies of specific subgroups in relation to the aetiology and natural course, also in non-clinical populations.

Conclusion

VESC is a common MRI-finding in patients with non-specific LBP and has been reported to be associated with pain in study samples from the general, working, and clinical populations.

References

Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, Hildebrandt J et al (2006) Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J 15(Suppl 2):S192–S300

Albert HB, Kjaer P, Jensen TS, Sorensen JS et al (2008) Modic changes, possible causes and relation to low back pain. Med Hypotheses 70:361–368. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2007.05.014

Albert HB, Manniche C (2007) Modic changes following lumbar disc herniation. Eur Spine J 16:977–982. doi:10.1007/s00586-007-0336-8

An HS, Vaccaro AR, Dolinskas CA, Cotler JM et al (1991) Differentiation between spinal tumors and infections with magnetic resonance imaging. Spine 16:S334–S338. doi:10.1097/00007632-199110001-00019

Annunen S, Paassilta P, Lohiniva J, Perala M et al (1999) An allele of COL9A2 associated with intervertebral disc disease. Science 285:409–412. doi:10.1126/science.285.5426.409

Appel H, Loddenkemper C, Grozdanovic Z, Ebhardt H et al (2006) Correlation of histopathological findings and magnetic resonance imaging in the spine of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther 8:R143. doi:10.1186/ar2035

Asazuma T, Nobuta M, Sato M, Yamagishi M et al (2003) Lumbar disc herniation associated with separation of the posterior ring apophysis: analysis of five surgical cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 145:461–466

Assheuer J, Lenz G, Lenz W, Gottschlich KW et al (1987) Fat/water separation in the NMR tomogram. The imaging of bone marrow reactions in degenerative intervertebral disk changes. Rofo 147:58–63

Aunoble S, Hoste D, Donkersloot P, Liquois F et al (2006) Video-assisted ALIF with cage and anterior plate fixation for L5–S1 spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord Tech 19:471–476. doi:10.1097/01.bsd.0000211249.82823.d9

Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Listing J, Haibel H et al (2005) Outcome of patients with active ankylosing spondylitis after two years of therapy with etanercept: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging data. Arthritis Rheum 53:856–863. doi:10.1002/art.21588

Baraliakos X, Davis J, Tsuji W, Braun J (2005) Magnetic resonance imaging examinations of the spine in patients with ankylosing spondylitis before and after therapy with the tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor fusion protein etanercept. Arthritis Rheum 52:1216–1223. doi:10.1002/art.20977

Baraliakos X, Landewe R, Hermann KG, Listing J et al (2005) Inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic description of the extent and frequency of acute spinal changes using magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Rheum Dis 64:730–734. doi:10.1136/ard.2004.029298

Baranto A, Hellstrom M, Nyman R, Lundin O et al (2006) Back pain and degenerative abnormalities in the spine of young elite divers: a 5-year follow-up magnetic resonance imaging study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14:907–914. doi:10.1007/s00167-005-0032-3

Battie MC, Haynor DR, Fisher LD, Gill K et al (1995) Similarities in degenerative findings on magnetic resonance images of the lumbar spines of identical twins. J Bone Joint Surg Am 77:1662–1670

Battie MC, Videman T, Parent E (2004) Lumbar disc degeneration: epidemiology and genetic influences. Spine 29:2679–2690. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000146457.83240.eb

Becker GT, Willburger RE, Liphofer J, Koester O et al (2006) Distribution of MRI signal alterations of the cartilage endplate in pre-operated patients with special focus on recurrent lumbar disc herniation. Rofo 178:46–54

Bennett DL, Nassar L, DeLano MC (2006) Lumbar spine MRI in the elite-level female gymnast with low back pain. Skeletal Radiol 35:503–509. doi:10.1007/s00256-006-0083-7

Braithwaite I, White J, Saifuddin A, Renton P et al (1998) Vertebral end-plate (Modic) changes on lumbar spine MRI: correlation with pain reproduction at lumbar discography. Eur Spine J 7:363–368. doi:10.1007/s005860050091

Bram J, Zanetti M, Min K, Hodler J (1998) MR abnormalities of the intervertebral disks and adjacent bone marrow as predictors of segmental instability of the lumbar spine. Acta Radiol 39:18–23

Braun J, Baraliakos X, Golder W, Brandt J et al (2003) Magnetic resonance imaging examinations of the spine in patients with ankylosing spondylitis, before and after successful therapy with infliximab: evaluation of a new scoring system. Arthritis Rheum 48:1126–1136. doi:10.1002/art.10883

Brown MF, Hukkanen MV, McCarthy ID, Redfern DR et al (1997) Sensory and sympathetic innervation of the vertebral endplate in patients with degenerative disc disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br 79:147–153. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.79B1.6814

Buttermann GR (2004) The effect of spinal steroid injections for degenerative disc disease. Spine J 4:495–505. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2004.03.024

Buttermann GR, Heithoff KB, Ogilvie JW, Transfeldt EE et al (1997) Vertebral body MRI related to lumbar fusion results. Eur Spine J 6:115–120. doi:10.1007/BF01358743

Buttermann GR, Mullin WJ (2008) Pain and disability correlated with disc degeneration via magnetic resonance imaging in scoliosis patients. Eur Spine J 17:240–249. doi:10.1007/s00586-007-0530-8

Carragee E, Alamin T, Cheng I, Franklin T et al (2006) Are first-time episodes of serious LBP associated with new MRI findings? Spine J 6:624–635. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2006.03.005

Carragee EJ, Alamin TF, Miller JL, Carragee JM (2005) Discographic, MRI and psychosocial determinants of low back pain disability and remission: a prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain. Spine J 5:24–35. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2004.05.250

Carrino JA, Swathwood TC, Morrison WB, Glover JM (2007) Prospective evaluation of contrast-enhanced MR imaging after uncomplicated lumbar discography. Skeletal Radiol 36:293–299. doi:10.1007/s00256-006-0221-2

Castro WH, Halm H, Jerosch J, Steinbeck J et al (1994) Long-term changes in the magnetic resonance image after chemonucleolysis. Eur Spine J 3:222–224. doi:10.1007/BF02221597

Champsaur P, Parlier-Cuau C, Juhan V, Daumen-Legre V et al (2000) Differential diagnosis of infective spondylodiscitis and erosive degenerative disk disease. J Radiol 81:516–522

Chataigner H, Onimus M, Polette A (1998) Surgery for degenerative lumbar disc disease. Should the black disc be grafted? Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar 84:583–589

Chung CB, Vande Berg BC, Tavernier T, Cotten A et al (2004) End plate marrow changes in the asymptomatic lumbosacral spine: frequency, distribution and correlation with age and degenerative changes. Skeletal Radiol 33:399–404. doi:10.1007/s00256-004-0780-z

Collins CD, Stack JP, O’Connell DJ, Walsh M et al (1990) The role of discography in lumbar disc disease: a comparative study of magnetic resonance imaging and discography. Clin Radiol 42:252–257. doi:10.1016/S0009-9260(05)82113-0

Cvitanic OA, Schimandle J, Casper GD, Tirman PF (2000) Subchondral marrow changes after laser diskectomy in the lumbar spine: MR imaging findings and clinical correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 174:1363–1369

Dagirmanjian A, Schils J, McHenry M, Modic MT (1996) MR imaging of vertebral osteomyelitis revisited. AJR Am J Roentgenol 167:1539–1543

Danchaivijitr N, Temram S, Thepmongkhol K, Chiewvit P (2007) Diagnostic accuracy of MR imaging in tuberculous spondylitis. J Med Assoc Thai 90:1581–1589

Danielsson AJ, Cederlund CG, Ekholm S, Nachemson AL (2001) The prevalence of disc aging and back pain after fusion extending into the lower lumbar spine. A matched MR study twenty-five years after surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Acta Radiol 42:187–197

de Roos A, Kressel H, Spritzer C, Dalinka M (1987) MR imaging of marrow changes adjacent to end plates in degenerative lumbar disk disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 149:531–534

Elfering A, Semmer N, Birkhofer D, Zanetti M et al (2002) Risk factors for lumbar disc degeneration: a 5-year prospective MRI study in asymptomatic individuals. Spine 27:125–134. doi:10.1097/00007632-200201150-00002

Esposito P, Pinheiro-Franco JL, Froelich S, Maitrot D (2006) Predictive value of MRI vertebral end-plate signal changes (Modic) on outcome of surgically treated degenerative disc disease. Results of a cohort study including 60 patients. Neurochirurgie 52:315–322. doi:10.1016/S0028-3770(06)71225-5

Fagan A, Moore R, Vernon RB, Blumbergs P et al (2003) ISSLS prize winner: the innervation of the intervertebral disc: a quantitative analysis. Spine 28:2570–2576. doi:10.1097/01.BRS.0000096942.29660.B1

Fayad F, Lefevre-Colau MM, Rannou F, Quintero N et al (2007) Relation of inflammatory modic changes to intradiscal steroid injection outcome in chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 16:925–931. doi:10.1007/s00586-006-0301-y

Flipo RM, Cotten A, Chastanet P, Ardaens Y et al (1996) Evaluation of destructive spondyloarthropathies in hemodialysis by computerized tomographic scan and magnetic resonance imaging. J Rheumatol 23:869–873

Freemont AJ, Peacock TE, Goupille P, Hoyland JA et al (1997) Nerve ingrowth into diseased intervertebral disc in chronic back pain. Lancet 350:178–181. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02135-1

Frobin W, Brinckmann P, Kramer M, Hartwig E (2001) Height of lumbar discs measured from radiographs compared with degeneration and height classified from MR images. Eur Radiol 11:263–269. doi:10.1007/s003300000556

Fruhwald F, Fruhwald S, Hajek PC, Schwaighofer B et al (1988) Focal fatty deposits in spinal bone marrow-MR findings. MRI of focal fatty deposits. Rofo 148:75–78

Gibson MJ, Buckley J, Mulholland RC, Worthington BS (1986) The changes in the intervertebral disc after chemonucleolysis demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging. J Bone Joint Surg Br 68:719–723

Gillams AR, Chaddha B, Carter AP (1996) MR appearances of the temporal evolution and resolution of infectious spondylitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 166:903–907

Gokhale YA, Ambardekar AG, Bhasin A, Patil M et al (2003) Brucella spondylitis and sacroiliitis in the general population in Mumbai. J Assoc Physicians India 51:659–666

Grand CM, Bank WO, Baleriaux D, Matos C et al (1993) Gadolinium enhancement of vertebral endplates following lumbar disc surgery. Neuroradiology 35:503–505. doi:10.1007/BF00588706

Grane P, Josephsson A, Seferlis A, Tullberg T (1998) Septic and aseptic post-operative discitis in the lumbar spine-evaluation by MR imaging. Acta Radiol 39:108–115

Gratz S, Dorner J, Fischer U, Behr TM et al (2002) 18F-FDG hybrid PET in patients with suspected spondylitis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 29:516–524

Hajek PC, Baker LL, Goobar JE, Sartoris DJ et al (1987) Focal fat deposition in axial bone marrow: MR characteristics. Radiology 162:245–249

Hamanishi C, Kawabata T, Yosii T, Tanaka S (1994) Schmorl’s nodes on magnetic resonance imaging. Their incidence and clinical relevance. Spine 19:450–453. doi:10.1097/00007632-199402001-00012

Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, Spindler MF et al (2007) Systematic review of tests to identify the disc, SIJ or facet joint as the source of low back pain. Eur Spine J 16:1539–1550. doi:10.1007/s00586-007-0391-1

Hayes CW, Jensen ME, Conway WF (1989) Non-neoplastic lesions of vertebral bodies: findings in magnetic resonance imaging. Radiographics 9:883–903

Herbsthofer B, Eysel P, Eckardt A, Humke T (1996) Diagnosis and therapy of erosive intervertebral osteochondrosis. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 134:465–471

Hermann KG, Bollow M (2004) Magnetic resonance imaging of the axial skeleton in rheumatoid disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 18:881–907. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2004.06.005

Hirji KF, Tsiatis AA, Mehta CR (1989) Median unbiased estimation for binary data. Am Stat 43:7–11. doi:10.2307/2685158

Hosten N, Lemke AJ, Mayer HM, Dihlmann SW et al (1995) Spondylitis: borderline findings in magnetic resonance tomography. Aktuelle Radiol 5:164–168

Hung-ta HW, William BM, Schweitzer ME (2006) Edematous Schmorls nodes on thoracolumbar MR imaging: characteristic patterns and changes over time. Skeletal Radiol 35:212–219. doi:10.1007/s00256-005-0068-y

Ito M, Incorvaia KM, Yu SF, Fredrickson BE et al (1998) Predictive signs of discogenic lumbar pain on magnetic resonance imaging with discography correlation. Spine 23:1252–1258. doi:10.1097/00007632-199806010-00016

Jarvik JG, Hollingworth W, Heagerty PJ, Haynor DR et al (2005) Three-year incidence of low back pain in an initially asymptomatic cohort: clinical and imaging risk factors. Spine 30:1541–1548. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000167536.60002.87

Jensen TS, Sorensen JS, Kjaer P (2007) Intra- and interobserver reproducibility of vertebral endplate signal (modic) changes in the lumbar spine: the Nordic Modic Consensus Group classification. Acta Radiol 48:748–754. doi:10.1080/02841850701422112

Jevtic V (2001) Magnetic resonance imaging appearances of different discovertebral lesions. Eur Radiol 11:1123–1135. doi:10.1007/s003300000727

Jevtic V, Kos-Golja M, Rozman B, McCall I (2000) Marginal erosive discovertebral “Romanus” lesions in ankylosing spondylitis demonstrated by contrast enhanced Gd-DTPA magnetic resonance imaging. Skeletal Radiol 29:27–33. doi:10.1007/s002560050005

Jevtic V, Majcen N (2004) Demonstration of evolution of hemispherical spondysclerosis by contrast enhanced Gd-DTPA magnetic resonance imaging. Radiol Oncol 38:275–284

Jim JJ, Noponen-Hietala N, Cheung KM, Ott J et al (2005) The TRP2 allele of COL9A2 is an age-dependent risk factor for the development and severity of intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine 30:2735–2742. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000190828.85331.ef

Jones A, Clarke A, Freeman BJ, Lam KS et al (2005) The Modic classification: inter- and intraobserver error in clinical practice. Spine 30(16):1867–1869

Kahn T, Weigert F, Reiser M, Heuck A et al (1987) The MRT demonstration of bone marrow changes in intervertebral disk degeneration. Rofo 147:320–324

Kapeller P, Fazekas F, Krametter D, Koch M et al (1997) Pyogenic infectious spondylitis: clinical, laboratory and MRI features. Eur Neurol 38:94–98. doi:10.1159/000113167

Karacan IM, Aydin TM (2006) Lumbar disc herniation in ankylosing spondylitis: a dual role of discovertebral enthesopathy. Neurosurg Q 16:74–76. doi:10.1097/00013414-200606000-00004 Article

Karchevsky M, Schweitzer ME, Carrino JA, Zoga A et al (2005) Reactive endplate marrow changes: a systematic morphologic and epidemiologic evaluation. Skeletal Radiol 34:125–129. doi:10.1007/s00256-004-0886-3

Karppinen J, Daavittila I, Solovieva S, Kuisma M et al (2008) Genetic factors are associated with modic changes in endplates of lumbar vertebral bodies. Spine 33:1236–1241

Karppinen J, Mikkonen P, Kurunlahti M, Tervonen O et al (2003) Chronic Chlamydia pneumoniae infection increases the risk of occlusion of lumbar segmental arteries of patients with sciatica: a 3-year follow-up study. Spine 28:E284–E289. doi:10.1097/00007632-200308010-00022

Karppinen J, Paakko E, Paassilta P, Lohiniva J et al (2003) Radiologic phenotypes in lumbar MR imaging for a gene defect in the COL9A3 gene of type IX collagen. Radiology 227:143–148. doi:10.1148/radiol.2271011821

Karppinen J, Paakko E, Raina S, Tervonen O et al (2002) Magnetic resonance imaging findings in relation to the COL9A2 tryptophan allele among patients with sciatica. Spine 27:78–83. doi:10.1097/00007632-200201010-00018

Kato F, Ando T, Kawakami N, Mimatsu K et al (1993) The increased signal intensity at the vertebral body endplates after chemonucleolysis demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging. Spine 18:2276–2281. doi:10.1097/00007632-199311000-00023

Kerttula LI, Serlo WS, Tervonen OA, Paakko EL et al (2000) Post-traumatic findings of the spine after earlier vertebral fracture in young patients: clinical and MRI study. Spine 25:1104–1108. doi:10.1097/00007632-200005010-00011

Kim JM, Lee SH, Ahn Y, Yoon DH et al (2007) Recurrence after successful percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 50:82–85. doi:10.1055/s-2007-982504

Kjaer P, Korsholm L, Bendix T, Sorensen JS et al (2006) Modic changes and their associations with clinical findings. Eur Spine J 15:1312–1319. doi:10.1007/s00586-006-0185-x

Kjaer P, Leboeuf-Yde C, Korsholm L, Sorensen JS et al (2005) Magnetic resonance imaging and low back pain in adults: a diagnostic imaging study of 40-year-old men and women. Spine 30:1173–1180. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000162396.97739.76

Kjaer P, Leboeuf-Yde C, Sorensen JS, Bendix T (2005) An epidemiologic study of MRI and low back pain in 13-year-old children. Spine 30:798–806. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000157424.72598.ec

Kleinstuck F, Dvorak J, Mannion AF (2006) Are “structural abnormalities” on magnetic resonance imaging a contraindication to the successful conservative treatment of chronic nonspecific low back pain? Spine 31:2250–2257. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000232802.95773.89

Kokkonen SM, Kurunlahti M, Tervonen O, Ilkko E et al (2002) Endplate degeneration observed on magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine: correlation with pain provocation and disc changes observed on computed tomography diskography. Spine 27:2274–2278. doi:10.1097/00007632-200210150-00017

Korhonen T, Karppinen J, Paimela L, Malmivaara A et al (2006) The treatment of disc herniation-induced sciatica with infliximab: one-year follow-up results of FIRST II, a randomized controlled trial. Spine 31:2759–2766. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000245873.23876.1e

Kowalski TJ, Layton KF, Berbari EF, Steckelberg JM et al (2007) Follow-up MR imaging in patients with pyogenic spine infections: lack of correlation with clinical features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 28:693–699

Kuisma M, Karppinen J, Niinimaki J, Kurunlahti M et al (2006) A three-year follow-up of lumbar spine endplate (Modic) changes. Spine 31:1714–1718. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000224167.18483.14

Kuisma M, Karppinen J, Niinimaki J, Ojala R et al (2007) Modic changes in endplates of lumbar vertebral bodies: prevalence and association with low back and sciatic pain among middle-aged male workers. Spine 32:1116–1122. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000261561.12944.ff

Lang P, Chafetz N, Genant HK, Morris JM (1990) Lumbar spinal fusion. Assessment of functional stability with magnetic resonance imaging. Spine 15:581–588. doi:10.1097/00007632-199006000-00028

Langlois S, Cedoz JP, Lohse A, Toussirot E et al (2005) Aseptic discitis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a retrospective study of 14 cases. Joint Bone Spine 72:248–253. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.05.015

Langlois S, Cedoz JP, Lohse A, Toussirot E et al (2005) Les spondylodiscites aseptiques de la spondylarthrite ankylosante : etude retrospective de 14 cas. Rev Rhum 72:420–426. doi:10.1016/j.rhum.2004.05.022

Laredo JD, Vuillemin-Bodaghi V, Boutry N, Cotten A et al (2007) SAPHO syndrome: MR appearance of vertebral involvement. Radiology 242:825–831. doi:10.1148/radiol.2423051222

Ledermann HP, Schweitzer ME, Morrison WB, Carrino JA (2003) MR imaging findings in spinal infections: rules or myths? Radiology 228:506–514. doi:10.1148/radiol.2282020752

Lee SI, Jin W (1999) MR imaging of Schmorl’s nodes and several factors influencing enhancement of Schmorl’s nodes. Riv Neuroradiol 12:191–192

Lenz GP, Assheuer J, Lenz W, Gottschlich KW (1990) New aspects of lumbar disc disease. MR imaging and histological findings. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 109:75–82. doi:10.1007/BF00439383

Lim CH, Jee WH, Son BC, Kim DH et al (2005) Discogenic lumbar pain: association with MR imaging and CT discography. Eur J Radiol 54:431–437. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.05.014

Liphofer JP, Theodoridis T, Becker GT, Koester O et al (2006) (Modic) signal alterations of vertebral endplates and their correlation to a minimally invasive treatment of lumbar disc herniation using epidural injections. Rofo 178:1105–1114

Liphofer JP, Theodoridis T, Becker GT, Koester O et al (2006) (Modic) signal alterations of vertebral endplates and their correlation to a minimally invasive treatment of lumbar disc herniation using epidural injections. Rofo 178:1105–1114

Lusins JO, Cicoria AD, Goldsmith SJ (1998) SPECT and lumbar MRI in back pain with emphasis on changes in end plates in association with disc degeneration. J Neuroimaging 8:78–82

Maksymowych WP, Dhillon SS, Park R, Salonen D et al (2007) Validation of the spondyloarthritis research consortium of Canada magnetic resonance imaging spinal inflammation index: is it necessary to score the entire spine? Arthritis Rheum 57:501–507. doi:10.1002/art.22627

Malinin T, Brown MD (2007) Changes in vertebral bodies adjacent to acutely narrowed intervertebral discs: observations in baboons. Spine 32:E603–E607

Marc V, Dromer C, Le Guennec P, Manelfe C et al (1997) Magnetic resonance imaging and axial involvement in spondylarthropathies. Delineation of the spinal entheses. Rev Rhum Engl Ed 64:465–473

Marzo-Ortega H, McGonagle D, O’Connor P, Emery P (2001) Efficacy of etanercept in the treatment of the entheseal pathology in resistant spondylarthropathy: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthritis Rheum 44:2112–2117. doi :10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2112::AID-ART363>3.0.CO;2-H

Mitra D, Cassar-Pullicino VN, McCall IW (2004) Longitudinal study of vertebral type-1 end-plate changes on MR of the lumbar spine. Eur Radiol 14:1574–1581. doi:10.1007/s00330-004-2314-4

Modic MT, Masaryk TJ, Ross JS, Carter JR (1988) Imaging of degenerative disk disease. Radiology 168:177–186

Modic MT, Steinberg PM, Ross JS, Masaryk TJ et al (1988) Degenerative disk disease: assessment of changes in vertebral body marrow with MR imaging. Radiology 166:193–199

Molla E, Marti-Bonmati L, Arana E, Martinez-Bisbal MC et al (2005) Magnetic resonance myelography evaluation of the lumbar spine end plates and intervertebral disks. Acta Radiol 46:83–88. doi:10.1080/02841850510016036

Moore RJ, Vernon-Roberts B, Osti OL, Fraser RD (1996) Remodeling of vertebral bone after outer anular injury in sheep. Spine 21:936–940. doi:10.1097/00007632-199604150-00006

Mulconrey DS, Knight RQ, Bramble JD, Paknikar S et al (2006) Interobserver reliability in the interpretation of diagnostic lumbar MRI and nuclear imaging. Spine J 6:177–184. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2005.08.011

Narvani AA, Tsiridis E, Wilson LF (2003) High-intensity zone, intradiscal electrothermal therapy, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Spinal Disord Tech 16:130–136

Ohtori S, Inoue G, Ito T, Koshi T et al (2006) Tumor necrosis factor-immunoreactive cells and PGP 9.5-immunoreactive nerve fibers in vertebral endplates of patients with discogenic low back pain and Modic Type 1 or Type 2 changes on MRI. Spine 31:1026–1031. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000215027.87102.7c

Paassilta P, Lohiniva J, Goring HH, Perala M et al (2001) Identification of a novel common genetic risk factor for lumbar disk disease. JAMA 285:1843–1849. doi:10.1001/jama.285.14.1843

Park SW, Lee JH, Ehara S, Park YB et al (2004) Single shot fast spin echo diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the spine; Is it useful in differentiating malignant metastatic tumor infiltration from benign fracture edema? Clin Imaging 28:102–108. doi:10.1016/S0899-7071(03)00247-X

Penta M, Sandhu A, Fraser RD (1995) Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of disc degeneration 10 years after anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine 20:743–747. doi:10.1097/00007632-199503150-00018

Peterson CK, Gatterman B, Carter JC, Humphreys BK et al (2007) Inter- and intraexaminer reliability in identifying and classifying degenerative marrow (Modic) changes on lumbar spine magnetic resonance scans. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 30:85–90. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.12.001

Putzier M, Schneider SV, Funk JF, Tohtz SW et al (2005) The surgical treatment of the lumbar disc prolapse: nucleotomy with additional transpedicular dynamic stabilization versus nucleotomy alone. Spine 30:E109–E114. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000154630.79887.ef

Quack C, Schenk P, Laeubli T, Spillmann S et al (2007) Do MRI findings correlate with mobility tests? An explorative analysis of the test validity with regard to structure. Eur Spine J 16:803–812. doi:10.1007/s00586-006-0264-z

Raininko R, Manninen H, Battie MC, Gibbons LE et al (1995) Observer variability in the assessment of disc degeneration on magnetic resonance images of the lumbar and thoracic spine. Spine 20:1029–1035. doi:10.1097/00007632-199505000-00009

Rajasekaran S, Babu JN, Arun R, Armstrong BR et al (2004) ISSLS prize winner: a study of diffusion in human lumbar discs: a serial magnetic resonance imaging study documenting the influence of the endplate on diffusion in normal and degenerate discs. Spine 29:2654–2667. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000148014.15210.64

Rannou F, Ouanes W, Boutron I, Lovisi B et al (2007) High-sensitivity C-reactive protein in chronic low back pain with vertebral end-plate Modic signal changes. Arthritis Rheum 57:1311–1315. doi:10.1002/art.22985

Raya JG, Dietrich O, Birkenmaier C, Sommer J et al (2007) Feasibility of a RARE-based sequence for quantitative diffusion-weighted MRI of the spine. Eur Radiol 17:2872–2879. doi:10.1007/s00330-007-0618-x

Ross JS, Zepp R, Modic MT (1996) The postoperative lumbar spine: enhanced MR evaluation of the intervertebral disk. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 17:323–331

Saifuddin A, Renton P, Taylor BA (1998) Effects on the vertebral end-plate of uncomplicated lumbar discography: an MRI study. Eur Spine J 7:36–39. doi:10.1007/s005860050024

Sandhu HS, Sanchez-Caso LP, Parvataneni HK, Cammisa FP Jr et al (2000) Association between findings of provocative discography and vertebral endplate signal changes as seen on MRI. J Spinal Disord 13:438–443. doi:10.1097/00002517-200010000-00012

Saywell WR, Crock HV, England JP, Steiner RE (1989) Demonstration of vertebral body end plate veins by magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Radiol 62:290–292

Schenk P, Laubli T, Hodler J, Klipstein A (2006) Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine: findings in female subjects from administrative and nursing professions. Spine 31:2701–2706. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000244570.36954.17

Schmid G, Witteler A, Willburger R, Kuhnen C et al (2004) Lumbar disk herniation: correlation of histologic findings with marrow signal intensity changes in vertebral endplates at MR imaging. Radiology 231:352–358. doi:10.1148/radiol.2312021708

Seki S, Kawaguchi Y, Mori M, Mio F et al (2006) Association study of COL9A2 with lumbar disc disease in the Japanese population. J Hum Genet 51:1063–1067. doi:10.1007/s10038-006-0062-9

Seymour R, Williams LA, Rees JI, Lyons K et al (1998) Magnetic resonance imaging of acute intraosseous disc herniation. Clin Radiol 53:363–368. doi:10.1016/S0009-9260(98)80010-X

Sharif HS, Aideyan OA, Clark DC, Madkour MM et al (1989) Brucellar and tuberculous spondylitis: comparative imaging features. Radiology 171:419–425

Shen M, Razi A, Lurie JD, Hanscom B et al (2007) Retrolisthesis and lumbar disc herniation: a preoperative assessment of patient function. Spine J 7:406–413. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2006.08.011

Siddiqui AH, Rafique MZ, Ahmad MN, Usman MU (2005) Role of magnetic resonance imaging in lumbar spondylosis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 15:396–399

Song KS, Ogden JA, Ganey T, Guidera KJ (1997) Contiguous discitis and osteomyelitis in children. J Pediatr Orthop 17:470–477. doi:10.1097/00004694-199707000-00012 Infection

Stabler A, Baur A, Kruger A, Weiss M et al (1998) Differential diagnosis of erosive osteochondrosis and bacterial spondylitis: magnetic resonance tomography (MRT). Rofo 168:421–428

Stabler A, Bellan M, Weiss M, Gartner C et al (1997) MR imaging of enhancing intraosseous disk herniation (Schmorl’s nodes). AJR Am J Roentgenol 168:933–938

Stabler A, Weiss M, Scheidler J, Krodel A et al (1996) Degenerative disk vascularization on MRI: correlation with clinical and histopathologic findings. Skeletal Radiol 25:119–126. doi:10.1007/s002560050047

Stumpe KD, Zanetti M, Weishaupt D, Hodler J et al (2002) FDG positron emission tomography for differentiation of degenerative and infectious endplate abnormalities in the lumbar spine detected on MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 179:1151–1157

Takeno K, Kobayashi S, Yonezawa T, Hayakawa K et al (2006) Salvage operation for persistent low back pain and sciatica induced by percutaneous laser disc decompression performed at outside institution: correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and intraoperative and pathological findings. Photomed Laser Surg 24:414–423. doi:10.1089/pho.2006.24.414

Tanigawa N, Komemushi A, Kariya S, Kojima H et al (2006) Percutaneous vertebroplasty: relationship between vertebral body bone marrow edema pattern on MR images and initial clinical response. Radiology 239:195–200. doi:10.1148/radiol.2391050073

Toyone T, Takahashi K, Kitahara H, Yamagata M et al (1994) Vertebral bone-marrow changes in degenerative lumbar disc disease. An MRI study of 74 patients with low back pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br 76:757–764

Trout AT, Kallmes DF, Layton KF, Thielen KR et al (2006) Vertebral endplate fractures: an indicator of the abnormal forces generated in the spine after vertebroplasty. J Bone Miner Res 21:1797–1802. doi:10.1359/jbmr.060723

Tyrrell PN, Davies AM, Evans N, Jubb RW (1995) Signal changes in the intervertebral discs on MRI of the thoracolumbar spine in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Radiol 50:377–383. doi:10.1016/S0009-9260(05)83134-4

Ulrich JA, Liebenberg EC, Thuillier DU, Lotz JC (2007) ISSLS prize winner: repeated disc injury causes persistent inflammation. Spine 32:2812–2819

Van Goethem JW, Parizel PM, Jinkins JR (2002) Review article: MRI of the postoperative lumbar spine. Neuroradiology 44:723–739. doi:10.1007/s00234-002-0790-2

Van Goethem JW, Parizel PM, van den Hauwe L, Van de Kelft E et al (2000) The value of MRI in the diagnosis of postoperative spondylodiscitis. Neuroradiology 42:580–585. doi:10.1007/s002340000361

Videman T, Battie MC, Ripatti S, Gill K et al (2006) Determinants of the progression in lumbar degeneration: a 5-year follow-up study of adult male monozygotic twins. Spine 31:671–678. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000202558.86309.ea

Virtanen IM, Song YQ, Cheung KMC, Ala-Kokko L et al (2007) Phenotypic and population differences in the association between CILP and lumbar disc disease. J Med Genet 44:285–288. doi:10.1136/jmg.2006.047076

Visuri T, Pihlajamaki H, Eskelin M (2005) Long-term vertebral changes attributable to postoperative lumbar discitis: a retrospective study of six cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res (433) 97–105. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000151425.00945.2a

Vital JM, Gille O, Pointillart V, Pedram M et al (2003) Course of Modic 1 six months after lumbar posterior osteosynthesis. Spine 28:715–720. doi:10.1097/00007632-200304010-00017

Voormolen MH, van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, van der Graaf Y et al (2006) Pain response in the first trimester after percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures with or without bone marrow edema. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 27:1579–1585

Wagner AL, Murtagh FR, Arrington JA, Stallworth D (2000) Relationship of Schmorl’s nodes to vertebral body endplate fractures and acute endplate disk extrusions. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 21:276–281

Wagner SC, Schweitzer ME, Morrison WB, Przybylski GJ et al (2000) Can imaging findings help differentiate spinal neuropathic arthropathy from disk space infection? Initial experience. Radiology 214:693–699

Weishaupt D, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N (1998) MR imaging of the lumbar spine: prevalence of intervertebral disk extrusion and sequestration, nerve root compression, end plate abnormalities, and osteoarthritis of the facet joints in asymptomatic volunteers. Radiology 209:661–666

Weishaupt D, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Min K et al (2001) Painful lumbar disk derangement: relevance of endplate abnormalities at MR imaging. Radiology 218:420–427

Wienands K, Lukas P, Albrecht HJ (1990) Clinical value of MR tomography of spondylodiscitis in ankylosing spondylitis. Z Rheumatol 49:356–360

Yong PY, Alias NAA, Shuaib IL (2003) Correlation of clinical presentation, radiography, and magnetic resonance imaging for low back pain—a preliminary survey. J Hong Kong Coll Radiol 6:144–151

Yuh WT, Marsh EEIII, Wang AK, Russell JW et al (1992) MR imaging of spinal cord and vertebral body infarction. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 13:145–154

Acknowledgment

This study is supported by grants from the Danish Foundation of Chiropractic Research and Postgraduate Education (Tue Secher Jensen).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jensen, T.S., Karppinen, J., Sorensen, J.S. et al. Vertebral endplate signal changes (Modic change): a systematic literature review of prevalence and association with non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J 17, 1407–1422 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-008-0770-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-008-0770-2