Abstract

Background

Prophylactic somatostatin to reduce the incidence of clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy remains controversial. We assessed the preventive efficacy of somatostatin on clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula in intermediate-risk patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy at pancreatic centres in China.

Methods

In this multicentre, prospective, randomised controlled trial, we used the updated postoperative pancreatic fistula classification criteria and cases were confirmed by an independent data monitoring committee to improve comparability between centres. The primary endpoint was the rate of clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula within 30 days after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Results

Eligible patients (randomised, n = 205; final analysis, n = 199) were randomised to receive postoperative intravenous somatostatin (250 μg/h over 120 h; n = 99) or conventional therapy (n = 100). The primary endpoint was significantly lower in the somatostatin vs control group (n = 13 vs n = 25; 13% vs 25%, P = 0.032). There were no significant differences for biochemical leak (P = 0.289), biliary fistula (P = 0.986), abdominal infection (P = 0.829), chylous fistula (P = 0.748), late postoperative haemorrhage (P = 0.237), mean length of hospital stay (P = 0.512), medical costs (P = 0.917), reoperation rate (P > 0.99), or 30 days’ readmission rate (P = 0.361). The somatostatin group had a higher rate of delayed gastric emptying vs control (n = 33 vs n = 21; 33% vs 21%, P = 0.050).

Conclusions

Prophylactic somatostatin treatment reduced clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula in intermediate-risk patients after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Trial registration

NCT03349424.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Currently, in high-volume surgical centres, mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is less than 3%; however, the incidence of major postoperative complications is 30–50% [1,2,3]. Clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula (CR-POPF) is the most common major complication after PD, with reported incidence rates of 10–28% [4, 5]. Current data suggest that CR-POPF is highly associated with reoperation rate and death risk.

To reduce the incidence of CR-POPF, perioperative suppression of pancreatic exocrine secretion using somatostatin, or a somatostatin analogue (octreotide or pasireotide) is a possible pharmacological approach. Results from studies evaluating this approach have varied; therefore, its value for preventing postoperative complications remains controversial.

There is significant heterogeneity in the POPF definition used [1,2,3,4,5]. In 2016, the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) updated the definition and grading criteria for POPF, making it possible to compare studies that evaluate the efficacy of drug treatment across different institutions (Online Resource 1). In 2017, ISGPS also recommended an intraoperative predictive scoring system to promote more clarity in patient risk stratification (Online Resource 2). The use of these tools in studies evaluating the prophylactic efficacy of somatostatin for CR-POPF in patients undergoing PD may help to clear the current controversy over whether their use is of clinical value. Improved clinical trial design may result in more definitive data to support treatment decisions and inform best practices.

Here, we conducted a multicentre, prospective, randomised controlled trial to evaluate perioperative somatostatin use for the prevention of CR-POPF in intermediate-risk patients undergoing PD. We present the following article in accordance with the CONSORT reporting checklist.

Methods

Ethics

This trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital. A contract research organisation (Tigermed Consulting Co., Ltd.) provided regulatory oversight by reviewing concealed patient data. All patients provided written informed consent after the nature and possible consequences of the study had been explained to them prior to participation. All authors had access to the study data and approved the final manuscript. This trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03349424). This trial was performed in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Patients

Patients were eligible for enrolment in this study if they were ≥ 18 years of age, scheduled to undergo PD, and had an intermediate-risk postoperative predictive fistula risk score (FRS) (Online Resource 2). Patients were excluded if they had a previous history of pancreatic surgery, received somatostatin/somatostatin analogue treatment < 5 half-life periods before surgery, had a known allergy to somatostatin or mannitol, or had any contraindication to somatostatin. Patients who did not undergo resection were withdrawn.

Study design

This was a multicentre, prospective, randomised controlled trial. After obtaining written informed consent, baseline laboratory tests and other examinations were conducted. The following information was collected from the operation record: type of pancreatic resection procedure, pancreatic texture, pancreatic duct diameter, and blood loss. Pathologic diagnoses were extracted from the frozen-section pathological reports. Pancreatic texture and blood loss were evaluated by the surgeon, whereas pancreatic duct diameter was measured on the resected specimen margin during the operation. Patients were risk-stratified intraoperatively using the prospectively validated clinical FRS [6]; determinate factors included gland texture, pathologic diagnosis, pancreatic duct diameter, and intraoperative blood loss. FRS was categorised as negligible risk (0 points), low-risk (1–2 points), intermediate-risk (3–6 points), and high-risk (7–10 points). Immediately following surgery, the investigator judged whether the inclusion/exclusion criteria were met, and intermediate-risk patients were randomised (1:1) during the operation to receive somatostatin (somatostatin group) or conventional therapy (control group) using an interactive web response system (dynamic randomisation method). Patients in the somatostatin group received a continuous intravenous infusion of somatostatin (250 μg/h; 30 mg total) beginning within 3 h of PD and for 120 h, in accordance with the requirements of the drug manual for stilamin. Good compliance was defined as a medication possession ratio of ≥ 80%. Patients in the control group did not receive somatostatin or any other somatostatin analogue.

Surgical intervention

PD surgeries were performed at six high-volume pancreatic surgery centres in China (each performing ≥ 100 PD surgeries annually) and by 2–4 pancreatic specialists at each centre. Pancreatic reconstruction was performed by pancreaticojejunostomy with a duct-to-mucosa anastomosis or invagination (at the surgeon’s discretion). Patients underwent full open surgery, full laparoscopic surgery, or laparoscopic assisted surgery. Free drains were placed in each patient near the pancreas-intestinal and choledochal-intestinal anastomotic stoma. According to the recommendation of ISGPS, drain removal is based on clinical (absence of fever) and laboratory arguments (dosage and kinetics of amylase in drains on postoperative D1, D3 ± D5).

Postoperative care was consistent in both groups. Usually, when the patient's gastrointestinal function recovers after PD (such as fart or defecation), and when there is no clinically related pancreatic fistula, oral diet will be resumed. All the patients used antibiotics (metronidazole + second-generation cephalosporins) within 72 h after PD. Laboratory values were assessed every other day; however, amylase levels in the drainage fluid were measured daily when drainage catheters were present. Cross-sectional abdominal imaging was performed if a possible intra-abdominal complication was suspected. Patients with CR-POPF were treated with somatostatin/somatostatin analogue until their drains were removed, regardless of their initial randomisation. The endpoints were reported by the attending or resident physician in second (Pod 5), third (discharge) and fourth (Pod 30) visits separately (Fig. 1).

Study outcomes

All patients were followed up for a minimum of 30 days, as surgery-related complications are generally expected to occur within 30 days of surgery; any postoperative or post-discharge complications were identified from chart reviews. Complications were reported by the attending or resident physician involved with each patient. CR-POPFs were further adjudicated by an independent data monitoring committee.

The primary endpoint was the rate of CR-POPF (Grades B and C POPF) as defined by the 2016 ISGPS criteria (Online Resource 1). Secondary endpoints included the rates of postoperative biochemical leak, morbidity, and the rate of other pancreatectomy-related complications as defined by the 2016 ISGPS criteria, Surgical Infection Society Revised Guidelines on the Management of Intra-Abdominal Infection [7] and the consensus statement on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of common complications after pancreatic surgery in China [8]. All adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 5.0).

Statistical analysis

We hypothesised that the rate of CR-POPF (within the 30 days following PD) for patients receiving conventional treatment could be reduced from 22% [9] to 7% [10, 11] with somatostatin treatment. To achieve 80% power with a one-sided type I error rate of 2.5%, a value of superiority of 0, and a 1:1 ratio of the two groups, we calculated a sample size of 86 patients per group. We then adjusted for a 5% drop-out rate for a final sample size of 91 patients per group. To further increase the study power and ensure adequate study participants, we aimed to enrol 200 patients (100 per group).

The full analysis set included all randomised patients who received at least one treatment and had a corresponding efficacy evaluation. The per-protocol population was a subset population that was consistent with the clinical trial protocol and was characterised by data on the primary endpoint, no major protocol deviations, and good compliance. The safety set included all patients who received at least one dose of treatment. Exploratory subgroup analysis of the rates of complications according to surgical approach (open PD or laparoscopy) was undertaken.

Summary statistics were reported as mean (standard deviation [SD]) for continuous variables or n (%) for categorical variables. Comparative analyses between groups were conducted using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics

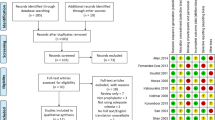

Patients were assessed for eligibility between June 2018 and May 2019; the flowchart and patient disposition are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. In total, 102 and 103 patients were assigned to the somatostatin and control groups, respectively (full analysis set). Three patients were excluded from each group in the final analysis: In somatostatin group, one patient had poor compliance, one had an inclusion deviation after randomisation, and one patient did not receive somatostatin; in control group, one patient did not meet the age criteria and two were lost to follow-up. Therefore, the per protocol set comprised 99 and 100 patients in the somatostatin and control groups, respectively.

Patient disposition. CR-POPF clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula, PD pancreaticoduodenectomy. aTo minimise selection bias, all PD operations performed by participating surgeons during the study period were initially evaluated (n = 658). Of these, 249 patients who were considered by investigators to have an intermediate risk of developing CR-POPF were assessed for eligibility; 205 patients were enrolled

The safety analysis set included all patients in the full analysis set except for two patients from the somatostatin group: one patient did not meet the inclusion criteria, and the other was moved to the control group because they did not receive somatostatin. Accordingly, the safety analysis set included 100 and 104 patients in the somatostatin and control groups, respectively.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups (Table 1). The mean (SD) age at the time of surgery was 58 (11) years in the somatostatin group and 59 (11) years in the control group. In addition, there were more male than female patients in the trial, including 57 (58%) male patients in the treatment group and 66 (66%) male patients in the control group. Details of intraoperative parameters are listed in Table 2; the types of PD procedures were similar between the groups. All patients received the drains and had an intermediate risk of POPF.

Study outcomes

Thirty-eight of the 199 patients who underwent randomisation (19%) had CR-POPF; of these, 34 (17%) patients were classified as Grade B and four (2%) as Grade C. Thirteen (13%) and 25 patients (25%) had CR-POPF in the somatostatin and control groups, respectively; the difference between groups was significant (P = 0.032) (Table 1).

Secondary endpoints

The rates of complications (secondary endpoints) are shown in Table 1. Biochemical leak was reported in 51 (52%) and 44 (44%) patients in the somatostatin and control groups, respectively (P = 0.289). The respective rates of biliary fistula (n = 6 vs n = 6; 6% vs 6%, P = 0.986), abdominal infection (n = 19 vs n = 18; 19% vs 18%, P = 0.829), chylous fistula (n = 5 vs n = 4; 5% vs 4%, P = 0.748), and late postoperative haemorrhage (n = 7 vs n = 12; 7% vs 12%, P = 0.237) were not significantly different between the two groups. The rate of delayed gastric emptying was higher in the somatostatin vs control group (n = 33 vs n = 21; 33% vs 21%, P = 0.050).

Exploratory subgroup analyses revealed that the rates of biochemical leak were similar between the somatostatin and control groups (n = 30 vs n = 27; 52% vs 39%) among patients receiving open PD (Table 3). Biochemical leak rates were also similar among patients who received laparoscopic PD (n = 21 vs n = 17; 51% vs 55%). In addition, in both subgroups categorised by surgical approach, the rates were similar for the somatostatin and control groups for other complications including biliary fistula, abdominal infection, chylous fistula, late postoperative haemorrhage, and delayed gastric emptying.

Length of hospital stay, and reoperation and readmission rates

The mean length of hospital stay was 24 and 23 days for the somatostatin and control groups, respectively (P = 0.512, Table 1). Two (2%) and three (3%) patients in the somatostatin and control groups, respectively, underwent reoperation within 30 days postoperatively (P > 0.99), and a respective four (4%) and seven (7%) patients were readmitted into hospital (P = 0.361, Table 1).

Among patients receiving open PD, the mean length of hospital stay was 26 days in the somatostatin group and 23 days in the control group. The rates of reoperation (n = 2 vs n = 1; 3% vs 1%) and readmission (n = 4 vs n = 4; 7% vs 6%) were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 3).

Among patients receiving laparoscopic PD, the mean length of hospital stay was 21 days in the somatostatin group and 23 days in the control group. The rates of reoperation (n = 0 vs n = 2; 0% vs 6%) and readmission (n = 1 vs n = 3; 2% vs 10%) were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 3).

Hospitalisation cost

The mean (SD) hospitalisation cost per patient was 115,069 (51,427) RMB yuan for the somatostatin group (including the cost of somatostatin) and 115,804 (51,881) yuan for the control group (P = 0.917, Table 1).

Adverse events

Among the 100 patients in the somatostatin group, the mean duration of exposure was 119.04 h. The mean exposure dose was 29.70 mg/person.

At least one adverse event was reported in 62/100 (62%) and 57/104 (55%) patients in the somatostatin and control groups, respectively (Table 4); serious adverse events were reported in two and four patients, respectively. Adverse drug reactions occurred in three patients in the somatostatin group. No serious adverse drug reactions or death were reported in the somatostatin group. In the control group, one patient died due to pneumonia and respiratory failure 97 days after PD.

Discussion

High-quality clinical trials are needed to elucidate the clinical benefit of prophylactic somatostatin in patients undergoing PD and to determine whether this preventative measure is warranted. Given that the risk for POPF is an important factor in determining the appropriateness of this approach, we designed a multicentre trial to evaluate the efficacy of prophylactic somatostatin in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenal resection with an intermediate risk of POPF. During the 1-year study period, we recruited, randomised, and analysed 199 patients, all of whom underwent a PD operation with surgical drains. The results indicated that prophylactic treatment with somatostatin significantly reduced the rate of CR-POPF compared with conventional treatment. Exploratory subgroup analysis showed that the decreased rate was observed whether patients underwent laparoscopic or open PD.

Some European studies have shown a decreased rate of POPF among patients who received perioperative somatostatin/somatostatin analogue [12, 13]; however, this has not been shown for patients in the US and the practice has been largely questioned [14, 15]. In 2014, a landmark trial showed that patients who received perioperative pasireotide (a somatostatin analogue) had a significant decrease in the rate of CR-POPF compared with conventional treatment (conventional treatment, 17%; pasireotide, 8%) [16]. This study fostered much debate and researchers expressed concern that it was a single-institution study, had a low rate of intraoperative drain placement (26%), and had no reported external validation of risk reduction. Moreover, rather than using an international grading system for pancreatic fistula, a single-centre grading system was used in the study. Thus, prophylactic use of somatostatin/somatostatin analogues for the reduction of CR-POPF remains controversial.

Our study showed a significant benefit for somatostatin use, and we speculate at least two possible reasons. First, the evaluation of CR-POPF may have been more reliable in our study owing to several factors: (1) we used the updated 2016 ISGPS criteria for POPF classification; (2) the nature of a prospective study makes evaluation of postoperative complications more reliable; and (3) CR-POPF was double adjudicated by an independent data monitoring committee (Professor Yinmo Yang from Peking University First Hospital and Professor Jingyong Xu from Beijing Hospital re-evaluated cases of CR-POPF, thus acting as independent data monitoring committee experts). We believe that these measures improved the comparability of results between the different institutions that participated in this study.

Second, factors influencing POPF [17] need to be standardised before the effects of somatostatin treatment can be evaluated. To accomplish this, our trial employed the FRS, which is a widely accepted method for evaluating POPF risk [9, 18]. We reported that the somatostatin and control groups were comparable with regard to gland texture, pathology, pancreatic duct diameter, and intraoperative blood loss. The ISGPS has recommended the prophylactic use of somatostatin/somatostatin analogues in patients with a high risk of POPF after PD. After the past 10 years’ literature reviewed and all opinions were carefully considered. This suggestion is also recommended by expert consensus in China [8]. Therefore, it is not in line with ethical requirements not to prophylactic use somatostatin/somatostatin analogues in high-risk groups. However, the prophylactic use of somatostatin in intermediate-risk patients remains controversial. Therefore, our trial specifically targeted patients with an intermediate risk of POPF. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomised controlled trial to explore the prophylactic use of somatostatin to reduce the rate of CR-POPF after PD using FRS as a criterion.

Although FRS was first proposed in 2015, there have been few studies evaluating fistula risk in intermediate-risk patients. Prior to conducting this study, we used previously published study results from our group [10] and others [9, 11] to estimate that the rate of CR-POPF could be reduced from 22 to 7% with somatostatin treatment. In this study, 13 (13%) and 25 patients (25%) had CR-POPF in the somatostatin and control groups, respectively, and the difference between groups was significant (P = 0.032). We believe that these results provide preliminary insight into whether prophylactic somatostatin/somatostatin analogues provide clinical benefit to intermediate-risk patients undergoing PD. However, further investigation of these findings in randomised control trials is warranted.

It is widely believed that surgical volume has an independent impact on the rate of POPF after PD [19,20,21]. In the present study, all surgical procedures were performed at six high-volume (performing > 100 PD surgeries annually) academic pancreatic surgery specialty centres. Additionally, prophylactic drains were placed during the initial operation for all patients in our study. We were, therefore, able to standardise the impact of patient characteristics, surgeon experience, perioperative care, and patient management on POPF.

The total CR-POPF rate in our study was 19%, which may be because we only included intermediate-risk patients, while other studies included patients at all risk levels. In a retrospective study using FRS, the rate of CR-POPF in intermediate-risk patients was 22% [9]. A CR-POPF rate of 19% may reflect the current surgical practice of incorporating the majority of patients undergoing pancreatic resection for diagnoses other than pancreatic cancer. CR-POPF risk and occurrence varies considerably among surgeons and institutions; historical data from institutions focusing on pancreatic cancer generally have lower CR-POPF rates, which is why disease pathology has been integrated into the clinical FRS algorithm.

We found that prophylactic somatostatin use did not reduce the rate of biochemical leak in intermediate-risk patients. This is in line with a previous study reporting that pasireotide did not reduce biochemical leak in patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy or PD [16]. This result should be further investigated as it cannot be explained by the pharmacological effects of somatostatin. The sample size of the current study was designed to assess the preventive efficacy of somatostatin on CR-POPF in intermediate-risk patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. However the rate of biochemical leakage in intermediate-risk patients is 42–67% [6, 9, 10]; the sample size (n = 199) might not be large enough to compare the preventive effects of somatostatin in biochemical leakage, and a larger sample size may have greater statistical power.

The rates of complications other than CR-POPF were not significantly different with the exception of the rate of delayed gastric emptying, which was increased in the somatostatin group (33% vs 21%, P = 0.050). The results are consistent with that of Shan et al. [22]. This may be explained by an inhibition of both gastrointestinal hormone secretion and gastrointestinal tract movement by somatostatin [23]. This is an important result as gastrointestinal function is closely related to patient recovery. We think this is the possible reason why there is no difference in hospital stay between the two groups.

CR-POPF is the most serious complication of PD and the exact correlation between CR-POPF and abdominal infection is continuously being investigated and is not clear [24]. On the one hand, studies have shown that abdominal infection is an important factor which may induce and aggravate the development of CR-POPF, and the bacteria in contaminated drain fluid may be the initial event for the development of CR-POPF [24]. On the other hand, abdominal infection can be induced by CR-POPF with the bacteria containing in pancreatic juice, bile, and intestinal juice leakaged from anastomosis [8]. Besides, preoperative chemotherapy, preoperative biliary drain, biliary fistula, abdominal bleeding, abdominal effusion, and pulmonary infection are also risk factors for the occurrence of abdominal infection [25,26,27,28]. At present, many risk factors are related to postoperative abdominal infection after PD. The current study indicated that prophylactic treatment with somatostatin significantly reduced the rate of CR-POPF; however, abdominal infection did not differ. We think this may be related to the above factors. And the result is also consistent with other studies [29,30,31].

Somatostatin and somatostatin analogues such as stilamin, octreotide, and pasireotide are commonly used in the clinic. However, in China, pasireotide is only indicated for treatment of acromegaly and, therefore, was not used in our study. It has previously been reported that octreotide primarily binds to somatostatin receptor subtypes 2 and 5, while stilamin binds with high affinity to all five somatostatin receptor subtypes [23]. Therefore, we elected to use stilamin in the present study because the primary somatostatin receptor subtypes in the pancreas are 1, 2, 3, and 5. As such, we considered that stilamin may be more effective than octreotide at reducing pancreatic exocrine secretions.

Our study had several limitations. First, patients and doctors were not blinded to the study treatment, as the ethics committee determined that intravenous infusion of normal saline was not in the best interest of patients in the control group. Second, the proportion of intermediate-risk patients (82.3%, 205/249) in our study was higher than reported in the literature (20–60%) [6, 9, 32]. This may be due to pre-screening as some patients not considered to be intermediate risk at the preoperative evaluation were not included during screening. To minimise selective bias, we counted all PD operations performed during the study period; the final proportion of intermediate-risk patients was 31.2% (205/658). Third, the evaluation of FRS and the grading of POPF are subjective as gland texture is difficult to quantify; all CR-POPF cases were independently re-evaluated by two specialists from two different pancreatic surgery centres to minimise subjective effects. Fourth, exploratory subgroup analysis showed that the decreased rate was observed whether patients underwent laparoscopic or open PD. However, the difference was not statistically significant. The sample size was not large enough to compare the preventive effects of somatostatin in open and laparoscopic PD; a larger sample size may have greater statistical power. Fifth, the primary endpoint (CR-POPF) and other complications were considered at 30 days after surgery. Generally, pancreatic fistulae most often develop within 30 days of surgery. Considering our limited research funding, we selected a follow-up time of 30 days after surgery. However, a 90-day follow-up period may be helpful in studies evaluating other complications or those investigating economic outcomes. Sixth, until now, few studies evaluated the rate of CR-POPF in intermediate risk patients. We hypothesised that the rate of CR-POPF for patients receiving conventional treatment could be reduced from 22 to 7% with somatostatin treatment, according to the report of Callery [9], Gouillat [11], and our previous exploratory study [10]. In the current study, the incidence of CR-POPF was 25% (control group) and 13% (somatostatin group). Although the incidence of CR-POPF in the current study is close to the predicted, the incidence of CR-POPF in intermediate risk patients still needs to be further verified. Studies with larger sample size are urgently needed. Seventh, the judgement of CR-POPF was based on clinical and laboratory finding (symptoms, laboratory findings, computerized tomography and so on). According to the study plan, the endpoints were reported by the attending or resident physician in second (Pod 5), third (discharge), and fourth (Pod 30) visits separately. The daily drain amylase levels in each centre were not recorded in raw CRF data. We were unable to evaluate the difference of daily drain amylase between the two groups. Finally, our study only included Chinese patients, potentially limiting the generalisability or our results.

These findings support a recommendation of routine prophylactic use of somatostatin in patients with an intermediate risk of CR-POPF. Given patient POPF risk level is expected to influence outcomes, we posit that clinical trials evaluating prophylactic somatostatin use in patients undergoing PD should incorporate some form of patient stratification. In addition, the use of methods to improve the reliability of CR-POPF evaluation should also be employed. It is anticipated that well-designed clinical trials that consider these factors may help clear the controversy surrounding somatostatin use and to further identify patients for whom this treatment is most appropriate.

References

Xiang Y, Wu J, Lin C, et al. Pancreatic reconstruction techniques after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a review of the literature. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:797–806.

Nahm CB, Connor SJ, Samra JS, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: a review of traditional and emerging concepts. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:105–18.

Wang J, Ma R, Churilov L, et al. The cost of perioperative complications following pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review. Pancreatology. 2018;18:208–20.

Cheng Y, Briarava M, Lai M, et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction for the prevention of postoperative pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9: CD012257.

Huttner FJ, Fitzmaurice C, Schwarzer G, et al. Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (pp Whipple) versus pancreaticoduodenectomy (classic Whipple) for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2: CD006053.

Shubert CR, Wagie AE, Farnell MB, et al. Clinical risk score to predict pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy: independent external validation for open and laparoscopic approaches. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:689–98.

Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, et al. Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:133–64.

Group of Pancreatic surgery, Surgical branch of Chinese Medical Association. A consensus statement on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of common complications after pancreatic surgery. Zhonghua wai ke za zhi Chinese J Surg 2017;55:328–334.

Callery MP, Pratt WB, Kent TS, et al. A prospectively validated clinical risk score accurately predicts pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:1–14.

Han XL, Xu J, Wu WM, et al. Impact of the 2016 new definition and classification system of pancreatic fistula on the evaluation of pancreatic fistula after pancreatic surgery. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2017;55:528–31 (Article in Chinese).

Gouillat C, Chipponi J, Baulieux J, et al. Randomized controlled multicentre trial of somatostatin infusion after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1456–62.

Volk A, Nitschke P, Johnscher F, et al. Perioperative application of somatostatin analogs for pancreatic surgery-current status in Germany. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2016;401:1037–44.

Adiamah A, Arif Z, Berti F, et al. The use of prophylactic somatostatin therapy following pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. World J Surg. 2019;43:1788–801.

Goyert N, Eeson G, Kagedan DJ, et al. Pasireotide for the prevention of pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Surg. 2017;265:2–10.

Dominguez-Rosado I, Fields RC, Woolsey CA, et al. Prospective evaluation of pasireotide in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: the Washington University experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226:147-54.e1.

Allen PJ, Gönen M, Brennan MF, et al. Pasireotide for postoperative pancreatic fistula. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2014–22.

Ratnayake CB, Loveday BP, Shrikhande SV, et al. Impact of preoperative sarcopenia on postoperative outcomes following pancreatic resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2018;18:996–1004.

Pulvirenti A, Marchegiani G, Pea A, et al. Clinical implications of the 2016 International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula on 775 consecutive pancreatic resections. Ann Surg. 2018;268:1069–75.

Brennan MF. Quality pancreatic cancer care: it’s still mostly about volume. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2009;101:837–8.

Gani F, Johnston FM, Nelson-Williams H, et al. Hospital volume and the costs associated with surgery for pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:1411–9.

Dusch N, Lietzmann A, Barthels F, et al. International study group of pancreatic surgery definitions for postpancreatectomy complications: applicability at a high-volume center. Scand J Surg. 2017;106:216–23.

Shan YS, Sy ED, Tsai ML, et al. Effects of somatostatin prophylaxis after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: increased delayed gastric emptying and reduced plasma motilin. World J Surg. 2005;29:1319–24.

Sun L, Coy DH. Somatostatin and its analogs. Curr Drug Targets. 2016;17:529–37.

Sato N, Kimura T, Kenjo A, et al. Early intra-abdominal infection following pancreaticoduodenectomy: associated factors and clinical impact on surgical outcome. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2020;66:124–32.

Chen JS, Liu G, Li TR, et al. Pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and preventive strategies. J Cancer Res Ther. 2019;15:857–63.

Watanabe F, Noda H, Kamiyama H, et al. Risk factors for intra-abdominal infection after pancreaticoduodenectomy—a retrospective analysis to evaluate the significance of preoperative biliary drainage and postoperative pancreatic fistula. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1270–3.

Qu G, Wang D, Xu W, et al. The systemic inflammation-based prognostic score predicts postoperative complications in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:787–95.

van Dongen JC, Wismans LV, Suurmeijer JA, et al. The effect of preoperative chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy on pancreatic fistula and other surgical complications after pancreatic resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. HPB (Oxford). 2021 May 19:S1365-182X(21)00143-X.

Wang XY, Cai JP, Huang CS, et al. Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery protocol on pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of non-randomized and randomized controlled trials. HPB (Oxford). 2020;22:1373–83.

Liu X, Chen K, Chu X, et al. Prophylactic intra-peritoneal drainage after pancreatic resection: an updated meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:658829.

Huan L, Fei Q, Lin H, et al. Is peritoneal drainage essential after pancreatic surgery? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96: e9245.

Mengyi L, Xiaozhen Z, Chenxiang G, et al. External validation of alternative fistula risk score (a-FRS) for predicting pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2020;22:58–66.

Acknowledgements

Writing support was provided by Sarah Bubeck, PhD, of Edanz Pharma. This study was funded by Merck Serono Ltd., Beijing, China, an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: TZ, BS, RQ, RC, YM, WL, YZ; Administrative support: JG, TZ, BS, RQ, RC, YM, WL, YZ; Provision of study materials or patients: JG, TZ, BS, RQ, RC, YM, WL, YZ; Collection and assembly of data: ZC, JQ, JG, GX, KJ, SZ, TK, YW; Data analysis and interpretation: ZC, JQ, JG, GX, KJ, SZ, TK, YW; Manuscript writing: all authors; Final approval of manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, Z., Qiu, J., Guo, J. et al. A randomised, multicentre trial of somatostatin to prevent clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula in intermediate-risk patients after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastroenterol 56, 938–948 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-021-01818-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-021-01818-8