Abstract

Background/purpose

In patients in whom there is a suspicion of malignant biliary strictures, bile cytology via an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube (ENBD cytology) is often performed, in addition to aspirated bile cytology, brush cytology, and forceps biopsy, during the initial endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). We aimed to reveal the significance of ENBD cytology for the pathological diagnosis of malignant biliary strictures.

Methods

We studied 214 patients with malignant biliary strictures. We performed aspirated bile cytology, brush cytology, and forceps biopsy in 93, 130, and 114 patients, respectively. ENBD cytology was performed one or more times in 79 patients. We examined the sensitivity of each sampling method, and analyzed the utility of ENBD cytology.

Results

The sensitivities of each sample acquisition method were as follows: 30% (28/93) for aspirated bile cytology, 48% (62/130) for brush cytology, 41% (47/114) for forceps biopsy, and 24% (19/79) for ENBD cytology. In 19 patients who showed positive ENBD cytology, other methods were performed in 11. Aspirated bile cytology, brush cytology, and forceps biopsy, were performed in 7, 5, and 6 patients, and the results were negative in 3 (43%), 2 (40%), and 1 (17%) patient, respectively. Three patients showed positive results only on ENBD cytology.

Conclusions

Although the sensitivity of ENBD cytology was inferior to that of the other methods used, ENBD cytology may contribute to the improvement of the total diagnostic sensitivity for malignancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Various benign and malignant diseases cause bile duct strictures. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish malignant diseases from benign ones by non-invasive imaging examinations only, such as abdominal ultrasonography or computed tomography. Pancreatic and biliary cancers account for most malignant biliary strictures. As superficial-spreading bile duct cancer causes bile duct strictures only and is not recognized as an evident mass on imaging examinations, it is often difficult to distinguish bile duct cancer from benign bile duct strictures. It is also difficult to diagnose pancreatic cancer, which mimics mass-forming type pancreatitis and autoimmune pancreatitis [1]. In order to make a definite diagnosis, it is important to obtain pathological evidence.

Four diagnostic methods performed during or after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are used in clinical practice for the pathological diagnosis of biliary strictures: (1) aspirated bile cytology, (2) brush cytology of the biliary stricture, (3) forceps biopsy of the biliary stricture, and (4) cytology of the bile via an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) tube (ENBD cytology). Although the usefulness of brush cytology and biliary forceps biopsy has been reported in many articles, the significance of bile cytology has not been discussed well because its sensitivity is generally lower than that of other methods [2–5].

In this retrospective study, we assessed the diagnostic ability of the 4 pathological diagnostic methods mentioned above, and explored the role of ENBD cytology in the pathological diagnosis of malignant biliary strictures.

Patients and methods

Patients

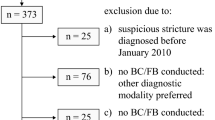

Between January 1999 and September 2008, 288 patients with biliary strictures received endoscopic biliary drainage at our facility. Among them, 251 patients underwent one or more sampling methods; that is, aspirated bile cytology, brush cytology, forceps biopsy, and ENBD cytology. Of these 251 patients, 214 (133 males, 81 females; mean age 68 years; range 38–89 years) were eventually diagnosed as having a malignancy, and these 214 patients were included in this study. The final diagnosis of malignancy was based on the surgical specimen in 77 patients, and on clinical follow-up in 137.

Methods

All patients gave their written informed consent to ERCP and specimen collection from the bile duct stricture. Ulinastatin and antibiotics were administered for the prevention of post-ERCP cholangitis and pancreatitis.

The ERCP procedure was conducted in the standard manner. Spasmolytic agents (scopolamine butylbromide or glucagon), diazepam, and pethidine hydrochloride were administered before insertion of the scope. A duodenoscope (JF-230, -240, -260v, TJF; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted to the second portion of duodenum. After selective bile duct cannulation, contrast medium (60% amidotrizoate sodium meglumine; Urografin, Nihon Schering, Osaka, Japan) was injected. After the level and length of biliary strictures was determined, a guidewire followed by a catheter was passed through the stricture, and bile above the stricture was collected for cytology. Once biliary access was secured with a guidewire, then intrahepatic opacification was completed, followed by intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS). Then brush cytology (RX cytology brush; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) and forceps biopsy (Radial Jaw 3; Boston Scientific) of the bile duct stricture was performed. The brush was advanced through the stricture with at least 10–20 to-and-fro movements. The forceps cup was pushed to the stricture for tissue sampling under fluoroscopy in most cases, and this procedure was performed 3 times in principle. Finally, a 7Fr ENBD tube, a 7Fr/8.5Fr plastic stent, or a metallic stent was placed for biliary drainage. Endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed when a metallic stent was placed in the patients with non-pancreatic cancer. Specimens were interpreted by pathologists experienced in gastrointestinal (GI) cytopathology and histopathology. Cytological findings were regarded as positive if the result was class 4 or 5, because all the patients with benign biliary strictures (n = 37) showed class 1–3 during the same study period. Patients were hospitalized after ERCP, and 10–20 ml of bile from the ENBD tube was collected for cytological examination 1–4 times. The ENBD tube was not always washed before collecting bile. Bile from a placed bag was never used. Once a positive result was obtained by ENBD cytology, further ENBD cytology was not performed, in principle. In some cases, ENBD cytology was performed even after a positive result was obtained, but the results of these cases were not included in the analysis.

In this study, first, the sensitivity of each sampling method was clarified. Then, in order to evaluate the clinical significance of adding ENBD cytology, we focused on the patients in whom ENBD cytology was performed. We investigated: (1) the results of the other sampling methods in these patients, (2) the difference in the sensitivities of ENBD cytology between bile duct cancer, gallbladder cancer, ampullary cancer, pancreatic cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and other malignancies, and (3) how much the sensitivity of ENBD cytology was improved by its repetition.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared by Fisher’s exact test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software JMP 7.0.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The final diagnoses of the 214 patients were bile duct cancer in 69 (extrahepatic in 50, and hilar in 19), gallbladder cancer in 32, ampullary cancer in 15, pancreatic cancer in 71, HCC in 10, and other malignancy in 17. During ERCP, aspirated bile cytology, brush cytology, and forceps biopsy were performed in 93, 130, and 114 patients, respectively. An ENBD tube was placed in 110 patients, and ENBD cytology was performed in 79. The distribution of diseases determined by each sampling method is shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference in distribution between any of the sampling methods (z test). ENBD cytology was performed once in 34 patients, twice in 18, three times in 20, and four times in 7. The sensitivities of each method for malignancy were 30% (28/93) for aspirated bile cytology, 48% (62/130) for brush cytology, 41% (47/114) for forceps biopsy, and 24% (19/79) for ENBD cytology. Limited to the first ENBD cytology, the sensitivity of this method was 14% (11/79). Overall, pathological diagnosis was confirmed in 115 patients (54%) by one or more sampling methods.

There were 28 patients in whom both ENBD cytology and aspirated bile cytology were performed. The results in these patients are summarized in Table 2.

Of 7 patients with a positive result on ENBD cytology, 3 patients (43%) showed a negative result on aspirated bile cytology. Similar analyses were performed for brush cytology and forceps biopsy (Tables 3, 4). There were 37 patients in whom both ENBD cytology and brush cytology were performed. Of 5 patients with a positive result on ENBD cytology, 2 patients (40%) showed a negative result on brush cytology. There were 33 patients in whom both ENBD cytology and forceps biopsy were performed. Of 6 patients with a positive result on ENBD cytology, one patient (17%) showed a negative result on forceps biopsy. The sensitivity of ENBD cytology was inferior to the sensitivities of the other methods, but the difference was not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test). The sensitivity of ENBD cytology in the patients with positive aspirated bile cytology was 50% (4/8), whereas that in the patients with negative aspirated bile cytology was much lower (15% [3/20]). This tendency was also recognized for the other methods; that is, 27% (3/11) versus 7.7% (2/26) for brush cytology, and 36% (5/14) versus 5.3% (1/19) for forceps biopsy.

There were 52 patients who received ENBD cytology and any of the other 3 sampling methods. When the other 3 methods were combined, their sensitivity was superior to that of ENBD cytology (42 vs. 21%, p = 0.037, Fisher’s exact test) (Table 5). However, there were still 3 patients who showed a positive result only on ENBD cytology. All of them were patients with bile duct cancer. In 2 of these patients, ENBD cytology and aspirated bile cytology were performed, and the latter method was negative. One of the 2 patients showed a positive result on the first ENBD cytology, and the other showed a positive result on the third ENBD cytology. In the third patient, all 3 of the methods other than ENBD cytology showed a negative result. This patient showed a positive result on the first ENBD cytology. Nine patients (3 patients with bile duct cancer, 1 with ampullary cancer, 4 with pancreatic cancer, and 1 with other malignancy) received all four sampling methods, and 5 patients (2 patients with bile duct cancer, 1 with ampullary cancer, and 2 with pancreatic cancer) showed negative results with all four methods.

ENBD cytology was performed in 30 patients with bile duct cancer, 10 with gallbladder cancer, 7 with ampullary cancer, 24 with pancreatic cancer, 4 with hepatocellular carcinoma, and 4 with other malignancy. The sensitivities of ENBD cytology for each disease were 33% (10/30), 10% (1/10), 29% (2/7), 17% (4/24), 25% (1/4), and 25% (1/4), respectively (Fig. 1). The sensitivity for bile duct cancer seemed to be better than that for pancreatic cancer, but the difference was not significant (p = 0.218).

The sensitivity of the first ENBD cytology was 14% (11/79). In the second, third, and fourth ENBD cytologies, the sensitivities were 8.9% (4/45), 15% (4/27), and 0% (0/7). By repeating ENBD cytology, cumulative sensitivity increased, that is, 14% (11/79) → 19% (15/79) → 24% (19/79) → 24% (19/79). The sensitivities for bile duct cancer in the first, second, and the third ENBD cytologies were 27% (8/30), 6.3% (1/16), and 11% (1/9), respectively, and those for pancreatic cancer were 8.3% (2/24), 0% (0/13), and 22% (2/9), respectively.

Discussion

The utilities of brush cytology and forceps biopsy for the diagnosis of malignancy have been reported in many articles. The sensitivities of brush cytology for malignancy range from 30 to 48% [2–8] and those of forceps biopsy range from 43 to 81% [5–10]. In our study, the sensitivities of brush cytology and forceps biopsy were 48 and 41%, respectively. This result does not seem to be greatly different from previous ones, though the sensitivity of forceps biopsy is unsatisfactory in comparison with the results of other studies from Japan which showed sensitivities of 81–88% for cholangiocarcinoma and 50–71% for pancreatic cancer [5, 9, 10]. In contrast to brush cytology and forceps biopsy, the significance of bile cytology has not been discussed well, because its sensitivity, which ranges from 6 to 32%, is generally lower than that of other methods [2–5]. There are few reports that have focused on ENBD cytology; however, Uchida et al. [11], by repeating the procedure many times, recently reported that its sensitivity could be surprisingly high, reaching 72.4%. Thus, we reviewed the results of ENBD cytology at our institute. We could not confirm such high sensitivity in our series, but there seem to be several reasons for our lower sensitivity. As our study was a retrospective one, ENBD cytology was not performed as often as it was in the series of Uchida et al. (2.0 vs. 2.8 times per patient on average). When the results of other methods such as brush cytology turned out to be positive soon after ERCP, we often skipped ENBD cytology, or we did not perform a second ENBD cytology if the first ENBD cytology could not confirm the positive result. Considering that ENBD cytology tends to be positive when other methods show positive results (Tables 2, 3, 4), it may be likely that ENBD cytology was repeated in the patients who had less possibility of showing a positive result. In addition, the series of Uchida et al. [11] included more patients with bile duct cancer than ours (74 vs. 38%), and this may have been responsible for the lower sensitivity in our series. That is, on brush cytology and forceps biopsy, it has been reported that bile duct cancer shows a positive result more frequently than pancreatic cancer [4, 5, 8, 9, 12]. This feature may also be true of ENBD cytology.

Comparisons between aspirated bile cytology and ENBD cytology have not been discussed so far. Although bile obtained from an ENBD tube may be less fresh than aspirated bile, ENBD cytology can be repeated. Therefore, we expected that the sensitivity of ENBD cytology might be no less high than that of aspirated bile cytology, but this was not the case. We think that the probable reasons for this result are a biased selection of patients and the bile from the ENBD tube being less fresh.

The repetition of ENBD cytology seemed to be useful for improving its sensitivity, but it is difficult to answer how often ENBD cytology should be repeated. From our results, it seems to be worth performing at least 3 times. On the other hand, the optimal number of repeated ENBD cytologies was concluded to be 6 in the report of Uchida et al. [11]. The more times ENBD cytology is repeated, the higher its sensitivity may become; however, we would like to choose performing brush cytology and forceps biopsy once again or performing endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) if we do want the pathological confirmation of malignancy. If ENBD cytology had been performed 6 times or more in all the patients in our study, this study might have been more valuable, at least from the viewpoint of its evaluation in comparison with the report of Uchida et al. [11].

As an ENBD tube, unlike a plastic stent, often causes discomfort to a patient [13], some doctors may want to avoid ENBD despite its additional effect on improving pathological diagnosis. In our series, among 26 patients who received the three sampling methods of brush cytology, forceps biopsy, and ENBD cytology, there was one who showed a positive result only on ENBD cytology. If it could be regarded as acceptable, ENBD would not be indicated in the patients who received, during the first ERCP, both brush cytology and forceps biopsy, which produced a combined sensitivity of 52% (46/88). In other cases, ENBD should be considered in terms of the pathological diagnosis. As it has been reported previously that ENBD and stent placement are equally safe, either choice would be acceptable in terms of complications [13, 14].

In summary, although the sensitivity of ENBD cytology for the diagnosis of malignant biliary strictures was lower than that of the other methods used, it sometimes showed a positive result even when another method showed a negative result. Especially when both brush cytology and forceps biopsy are not performed for some reasons in patients in whom there is a suspicion of bile duct cancer, ENBD cytology may contribute to the improvement of the total diagnostic sensitivity for malignancy.

References

Hirano K, Komatsu Y, Yamamoto N, Nakai Y, Sasahira N, Toda N, et al. Pancreatic mass lesions associated with raised concentration of IgG4. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2038–40.

Foutch PG, Kerr DM, Harlan JR, Kummet TD, et al. A prospective, controlled analysis of endoscopic cytotechniques for diagnosis of malignant biliary strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:577–80.

Davidson B, Varsamidakis N, Dooley J, Deery A, Dick R, Kurzawinski T, et al. Value of exfoliative cytology for investigating bile duct strictures. Gut. 1992;33:1408–11.

Mansfield JC, Griffin SM, Wadebra V, Matthewson K, et al. A prospective evaluation of cytology from biliary strictures. Gut. 1997;49:671–7.

Sugiyama M, Atomi Y, Wada N, Kuroda A, Muto T, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary bile duct biopsy without sphincterotomy for diagnosing biliary strictures: a prospective comparative study with bile and brush cytology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:465–7.

Schoefl R, Haefner M, Wrba F, Pfeffel F, Stain C, Poetzi R, et al. Forceps biopsy and brush cytology during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for the diagnosis of biliary stenoses. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:363–8.

Jailwala J, Fogel EL, Sherman S, Gottlieb K, Flueckiger J, Bucksot LG, et al. Triple-tissue sampling at ERCP in malignant biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:383–90.

Ponchon T, Gagnon P, Berger F, Labadie M, Liaras A, Chavaillon A, et al. Value of endobiliary brush cytology and biopsies for the diagnosis of malignant bile duct stenosis: results of a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:565–72.

Kubota Y, Takaoka M, Tani K, Ogura M, Kin H, Fujimura K, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary biopsy for diagnosis of patients with pancreaticobiliary ductal strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1700–4.

Tamada K, Tomiyama T, Wada S, Ohashi A, Satoh Y, Ido K, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary bile duct biopsy with the combination of intraductal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of biliary strictures. Gut. 2002;50:326–31.

Uchida N, Kamada H, Ono M, Aritomo Y, Masaki T, Nakatsu T, et al. How many cytological examinations should be performed for the diagnosis of malignant biliary stricture via an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1501–4.

Vandervoort J, Soetikno RM, Montes H, Lichtenstein DR, Van Dam J, Ruymann FW, et al. Accuracy and complication rate of brush cytology from bile duct versus pancreatic duct. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:322–7.

Lee DW, Chan AC, Lam YH, Ng EK, Lau JY, Law BK, et al. Biliary decompression by nasobiliary catheter or biliary stent in acute suppurative cholangitis: a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:361–5.

Sharma BC, Kumar R, Agarwal N, Sarin SK, et al. Endoscopic biliary drainage by nasobiliary drain or by stent placement in patients with acute cholangitis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:439–43.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Yagioka, H., Hirano, K., Isayama, H. et al. Clinical significance of bile cytology via an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage tube for pathological diagnosis of malignant biliary strictures. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 18, 211–215 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-010-0333-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-010-0333-x