Abstract

Purpose

Cognitive decline is one of the main side effects of breast cancer patients after relevant treatment, but there is a lack of clear measures for prevention and management without definite mechanism. Moreover, postoperative patients also have a need for limb rehabilitation. Whether the cognitive benefits of Baduanjin exercise can improve the overall well-being of breast cancer patients remains unknown.

Methods

This randomized controlled trial was conducted on 70 patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy who were randomly assigned and allocated to (1:1) a supervised Baduanjin intervention group (5 times/week, 30 min each time) or a control group for 3 months. The effects of Baduanjin exercise intervention were evaluated by outcome measures including subjective cognitive function, symptoms (fatigue, depression, and anxiety), and health-related quality of life at pre-intervention (T0), 4 weeks (T1), 8 weeks (T2), and 12 weeks (T3). The collected data were analyzed by using an intention-to-treat principle and linear mixed-effects modeling.

Results

Participants in the Baduanjin intervention group had a significantly greater improvement in terms of FACT-Cog (F = 14.511; p < 0.001), PCI (F = 15.789; p < 0.001), PCA (F = 6.261; p = 0.015), and FACT-B scores (F = 8.900; p = 0.004) compared with the control group over the time. The exercise-cognition relationship was significantly mediated through the reduction of fatigue (indirect effect: β = 0.132; 95% CI 0.046 to 0.237) and the improvement of anxiety (indirect effect: β = − 0.075; 95% CI − 0.165 to -0.004).

Conclusions

This pilot study revealed the benefits of Baduanjin exercise for subjective cognition and health-related quality of life of Chinese breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and outlined the underlying mediating mechanism of exercise-cognition. The findings provided insights into the development of public health initiatives to promote brain health and improve quality of life among breast cancer patients.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR 2,000,033,152.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cognitive impairment in cancer patients, also known as cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI), is mostly attributed to cancer and treatment with chemotherapeutic agents, hormone therapy, and radiation therapy [1]. CRCI is predominately characterized by changes in memory, processing speed, attention or concentration, and executive function [2, 3], which manifest during or after treatment with variable degrees, onset, and duration. Up to 75% of cancer patients experience mild to severe cognitive complaints, which can persist for months or even a few years after the completion of treatment [4]. Cognitive complaints are the most frequent complication reported by breast cancer (BC) patients [5]. Namely, more than 50% of these patients experience cognitive impairment following chemotherapy; however, only 15–25% of these cancer patients show poor performance in objective cognition [6]. These BC patients may experience difficulties in daily functioning, decision-making, multitasking, word retrieval, as well as treatment adherence; therefore, CRCI has become one of the prevalent factors that compromise the quality of life (QoL) and decrease survival [7].

As the exact underlying mechanism and etiology of CRCI are still unclear, recent preclinical and clinical studies have proposed several candidates, including inflammation. Affected cancer patients show increased levels of proinflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [8,9,10,11]; meanwhile, they show decreased serum levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) [11]. Other underlying mechanisms contributing to CRCI include chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity, blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption, decreased hippocampal neurogenesis, white matter abnormalities, secondary neuroinflammatory response, and increased oxidative stress [12]. In addition, pervasive fatigue and negative emotions may contribute to the increased susceptibility to cognitive impairment. There is a moderate positive correlation between subjective cognitive impairment and fatigue in postmenopausal BC patients [13]. A previous study found that BC patients undergoing systemic treatment had higher levels of fatigue symptoms and more subjective cognitive problems along with the decline of executive function [14]. Previous results [15] showed that the subjective cognitive function of BC patients after 6 months of chemotherapy was significantly lower than that before chemotherapy, and the cognitive impairment correlated with anxiety and depression. However, another study reported the lack of association between cognitive impairment and depression [16].

There is currently a great need for therapeutic interventions that can reduce these cognitive complaints after cancer treatment. To date, intervention studies to alleviate CRCI mainly have focused on physical activity, cognitive training, and pharmacological intervention [17]. Exercise is an established safe and effective therapy for managing numerous adverse effects of cancer treatment, including fatigue, psychological distress, functional decline, and detrimental body composition changes [18,19,20]. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) has shown that regular physical activity could promote brain health, thereby having substantial social and economic impacts. Accumulating evidence for the exercise-related improvement in cognitive function of healthy older adults and those with mild cognitive impairment or more severe neurocognitive impairment (i.e., Alzheimer’s disease (AD), stroke) has sparked significant interest in the potential use of exercise as an effective management strategy for CRCI [21, 22]. Numerous studies have shown that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) can mitigate and ameliorate cognitive impairment in BC patients, especially in terms of processing speed, executive function, and working memory [23,24,25]. Two pilot studies have shown that aerobic exercise improves objective cognition in patients with BC after primary treatment. One study [24] reported that a 12-week exercise intervention improved the processing speed in patients diagnosed with BC in the preceding 2 years, but there was no significant improvement in self-reported cognitive function. Another study showed that a 24-week supervised and home-based aerobic exercise program demonstrated similar results in postmenopausal women with early-stage BC [26]. Nevertheless, another study [27] showed that aerobic exercise plus resistance training programs improved subjective cognitive function from a subscale of health-related quality of life scale (EORTC-QLQ-C30) and decreased the level of CRP. Unfortunately, due to limited preclinical studies, testing of the antitumor activity of exercise is restricted and evidence-based recommendations are insufficient; therefore, more rigorous studies are warranted.

Baduanjin, one of the most common forms of Qigong exercise [28], is a low-moderate intensity aerobic exercise [29], which is beneficial for fatigue, QoL, and negative mood among patients [19, 20]. It promotes the health of the brain and nervous system mainly through internal movement, static movement, and the combination of the two. Regular Baduanjin exercise can improve the cognitive function of older individuals or patients with mild cognitive impairment after stroke. Studies are also present on medical Qigong to improve the cognitive function of BC patients. For example, one study [30] showed that self-cognition function, executive function, and language fluency improved in the Qigong group after 8 weeks of intervention. In light of the high withdrawal rate and poor adherence in that study, the effect of exercise on cognitive functioning in BC patients needs further exploration.

Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to explore the effects of the Baduanjin exercise program on cognitive function and health-related QoL in chemotherapy-exposed patients with early-stage BC. Moreover, this study aimed to examine whether or not cancer-related symptoms (fatigue, depression, and anxiety) mediate the effect of exercise training on cognition.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a single-blinded randomized controlled trial with two study arms, including a supervised Baduanjin intervention group and a control group. Participants were recruited from the three affiliated hospitals of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine: Yueyang Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, Seventh People’s Hospital, and Longhua Hospital. The outcome measures were evaluated in a quiet room in the hospital to avoid interference.

Participants

The participants were randomly assigned to a Baduanjin intervention group or a control group in a 1:1 ratio using SPSS 24.0 software. Researchers screened BC patients satisfying the inclusion and exclusion criteria through electronic medical records and provided relevant information brochures of the study, as well as possible benefits of the exercise and the safety. In addition, recruitment posters were posted in the hospitals and via social media such as WeChat, an online communication app. After obtaining consent, the research team examined the candidates using the patients’ questionnaire. Other parameters such as height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI) were recorded. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) female patients newly diagnosed with stage I to III BC; (2) those scheduled to receive chemotherapy; (3) those aged 40 to 75 years; (4) those who used WeChat; (5) those who had sufficient fluency in the Chinese language; and (6) those who were willing to participate in the study and be randomly assigned. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with disease recurrence or metastasis; (2) those with known conditions and/or diseases that impact cognition (e.g., AD, dementia, or other psychological diagnoses); (3) those with conditions in which exercise training is contraindicated according to the ACSM [31]; and (4) those with current/planned participation in mindfulness-based exercise programs (e.g., TaiChi or Qigong). Due to the nature of exercise studies, only evaluators of the results were blinded. More details were presented in the previous protocol of the study [32].

Sample size estimation

The sample size was estimated by using perceptive cognitive impairment as the main effect indicator, referring to the results of a previous study [33]. Using the G*Power 3.1 software, a total of 58 cases were required to ensure the power of 0.80. Considering a 20% dropout rate, the total sample size for this study was about 70 patients randomized to the intervention group or the control group.

Study interventions

Baduanjin intervention

Baduanjin exercise was conducted in accordance with the standards promulgated by the General Administration of Sport in China in 2003. It consists of 10 postures (including the beginning and the ending posture). A professionally trained Qigong specialist uniformly trained the researchers to learn the exercise training. The researchers then conducted on-site instruction to guide the participants and correct their movements. The participants were also provided a video demonstration to promote daily practice. Before initiating the first cycle of chemotherapy, the patients had the first session in the hospital, followed by a video workout at home. Recommended training time was five times a week for half an hour each time during the 12-week exercise period. The program began with stretching the joints, inhalation and exhalation for 2 min each, and two 12-min Baduanjin sessions, followed by 2 min of muscle relaxation exercises. Each patient’s log was recorded during exercise at home, including any obstacles that affected exercise training. When a patient went to the hospital to receive the next cycle of chemotherapy, the feedback of the exercise log was collected and checked.

Control intervention

Patients randomized to the control group were given face-to-face interviews in accordance with a brochure to maintain their usual healthy lifestyle. Disease-related questions raised by the patients were directly communicated or answered through WeChat online or oral communication. According to the guideline and standard for the diagnosis and treatment of BC in China [34], postoperative patients promoted rehabilitation of affected limb through regular physical activity, including abduction, forward flexion, backward extension, internal rotation, and wall climbing. The patients were not asked to conduct other aerobic activities. The researchers asked about their conditions twice a week for 12 weeks.

Measurements

Socio-demographic profile

At baseline, a self-designed demographic data sheet was used to collect the socio-demographic data, including age, BMI, marital status, income, education, and living condition, as well as relevant disease information from the electronic medical system.

Outcome measurements

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function (FACT-Cog) was developed by Wagner et al. [35] to assess subjective cognitive function; here, the Chinese version of the FACT-Cog was used. The Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-SF) was used to assess the fatigue of patients in multiple aspects [36]. A Taiwanese scholar then revised the Chinese version of the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-SF-C) [37], which was used in this study. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used for the assessment of patients’ anxiety and depression [38]. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B), a 44-item self-report instrument, is well-known and widely used to measure the multidimensional quality of life (QoL) in patients with BC [39]. The Constant–Murley score [40] was used to assess the patient’s shoulder mobility in this study.

Procedure and ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Seventh People’s Hospital of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 2020-7th-HIRB-011). The purpose and process were explained to the potential participants. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Each of the participants was assured of confidentiality and the option to decline participation or to withdraw from the trial at any time without penalty. Baseline data collection was conducted by two trained research assistants. After the pre-test data collection, the participants were randomly allocated to receive the Baduanjin exercise program or the control group. The post-test data were collected at 4 weeks (T1), 8 weeks (T2), and 12 weeks (T3) of intervention.

Data analysis

Demographic and other characteristics were reported descriptively using the statistics software (SPSS 24.0). The mean with standard deviation (SD) was calculated for continuous normally distributed variables, and the median with range was used for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were presented by absolute numbers and percentages. We performed complete case analyses after describing the pattern of missing data.

According to the intention-to-treat principle, a linear mixed-effect model for repeated-measures analysis was used, in which group, time point, and the interaction between group and time point were set as fixed effects; the individual patient was set as the random effect; and age was a covariate in the model. Adherence to the Baduanjin exercise was noted. The two-sided significance level for all tests was 0.05. The PROCESS macro [41] was employed to examine the mediating effects of fatigue and anxiety on the relationship between exercise and subjective cognition. Specifically, 95% confidence intervals for direct and indirect effects were generated via bias-corrected bootstrapping with 10,000 resamples. The nonparametric bootstrapping procedures are superior to traditional regression methods for testing the mediating effects because the former does not make assumptions regarding the shape of the distribution of the variables or the sampling distribution [42].

Results

Recruitment

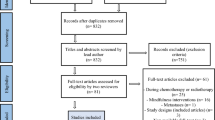

As shown in the CONSORT flow diagram (Fig. 1), 107 BC patients were approached for eligibility screening. Among them, 70 participants met the selection criteria and consented to participate. During the study period, according to the results of the exercise diary, 24 of 35 patients (80%) had a completion rate > 85%, which could be considered as good compliance. Three patients dropped out of the study on account of severe diarrhea after chemotherapy (n = 1) or voluntarily withdrew (n = 2). No adverse events, such as lymphedema related to exercise, occurred.

Participants’ characteristics

The median age of the included patients was 55 (46, 60) years. The majority of the participants were married and relatively poorly educated (52.9% with a junior high school education or less), and 68.6% of the patients were menopausal. The majority of the participants were early BC patients (stage I–II), with 50% in stage II. Anthracyclines accounted for 51.4% of all chemotherapy regimens, and non-anthracyclines for 48.6%; 7.1% were exposed to chemotherapy regimens combined with targeted therapy. BC patients with comorbidities accounted for 24.3%. The demographic and clinical disease characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. No considerable differences were observed between the groups at baseline.

Effects on cognitive function

FACT-Cog scores of both groups at the fourth, eighth, and 12th weeks are presented in Table 2. Participants in the Baduanjin intervention group had a significantly greater improvement in their FACT-Cog score compared with the control group across the baseline and post-intervention periods (F = 14.511; p < 0.001). Among all the subscales of FACT-Cog, the results were significant for perceived cognitive impairment (F = 15.789; p < 0.001), perceived cognitive ability (F = 6.261; p = 0.015), the impact of cognition on the quality of life (F = 17.428; p < 0.001), and significant differences were found in the comments from others (F = 9.359; p < 0.001).

Effects on health-related QoL

FACT-B scores of both groups at the fourth, eighth, and 12th weeks are presented in Table 3. Participants in the intervention group had a significantly greater improvement in FACT-B score compared with the control group across the baseline and post-intervention periods (F = 8.900; p = 0.004). Among the FACT-B items, the mixed-effect modeling results were significant for physical well-being (F = 4.908; p = 0.03) and emotional well-being (F = 7.640; p = 0.007) (Supplementary Figure 3). No significant differences were found in terms of social/family function, functional well-being, and additional attention. The scores of the FACT-B and Constant–Murley scores in both groups of BC patients were improved, but the Baduanjin intervention group was significantly better than the control group (see Supplementary material).

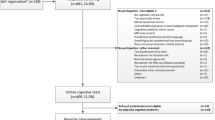

Results of the mediating analysis

Through linear regression analysis, the FACT-Cog score showed a linear correlation with fatigue score (β = − 0.392, p < 0.001), and it had a linear correlation with anxiety score (β = 0.339, p = 0.001). There was no correlation between FACT-Cog score and depression score (β = − 0.053, p = 0.585). On this basis, a mediation hypothesis model of fatigue and anxiety was established. After putting fatigue and anxiety into intermediary variables through SPSS PROCESS, the result of the analysis of the intermediary model is shown in Fig. 2. Exercise had a negative effect on anxiety (β = − 0.795, t = − 2.105, p < 0.05) and fatigue (β = − 0.733, t = − 3.319, p < 0.001), while it had a significant positive effect on cognition (β = 5.875, t = 5.932, p < 0.001). Fatigue showed a significant negative effect on subjective cognitive ability (β = − 1.618, t = − 4.432, p < 0.001). The exercise intervention elicited a significant indirect effect on the enhancement of cognitive function through the reduction of fatigue (indirect effect: β = 0.132; 95% CI 0.046 to 0.237) and the improvement of anxiety (indirect effect: β = − 0.075; 95% CI − 0.165 to -0.004).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of a 12-week Baduanjin exercise program on cognitive function, cancer-related symptoms, and QoL in patients with BC receiving chemotherapy, and to clarify the mechanisms underlying the exercise-cognition relationship. This study echoed the cognitive-enhancing benefits of other aerobic and mind–body exercises in the BC population. Our findings implied that Baduanjin could improve subjective cognitive impairment among patients with BC compared with regular health education. By incorporating a mediating analysis, this study added further evidence to indicate that cognitive benefits of physical exercise are manifested through its positive effects on two cognitive risk factors, including fatigue and anxiety. This exercise intervention also effectively improved cognitive function and the overall well-being of BC patients.

Cognitive benefits of exercise

The subjective feeling of cancer patients is the most relevant measure of clinical significance, and the self-reported cognition of patients should be used as the main outcome indicator for CRCI. The cognitive benefits of the 12-week Baduanjin exercise are consistent with the findings reported in previous studies for BC patients. However, no statistical significance was found at the fourth week, which may be because BC patients were in the postoperative recovery period, and their postures for exercise could not be fully standardized at that time. At the same time, the lack of significant difference in the shoulder joint function scores between the two groups could also explain such a result. A previous study [30] indicated that a longer-term exercise training of at least 8 weeks was needed to produce such a beneficial effect. Another randomized controlled study [33] conducted a 10-week medical Qigong intervention, which showed similar results. In the present study, we developed an exercise practice protocol of a shorter duration (i.e., 8 weeks) to achieve a similar effect. However, a previous study [43] in BC patients who performed 90 min of small-group yoga sessions twice a week for 12 weeks did not find significant improvement after intervention. Several design characteristics of the exercise program may explain such differences. First, our 12-week exercise program was developed in accordance with the recommendations of the ACSM, so that BC patients would have regular and supervised exercise five times a week. Second, the use of Baduanjin exercise rather than Qigong or yoga may be an available form of exercise to help the participants reach moderate-intensity exercise training. The mind–body exercise with upper limb movements satisfied daily activities, avoiding tediousness and supporting good body movement. Clearly, Baduanjin exercise has a certain preventive effect on the decline of subjective cognitive ability of BC patients during chemotherapy, but the continuous effect of Baduanjin intervention on cognitive ability after the end of the 12-week Baduanjin intervention was not observed due to personnel and time constraints, which can be further observed in future large-sample studies.

Effects of exercise on health-related QoL

Due to cancer, cancer treatment, or combination with other diseases, BC patients develop long-term physical and psychological conditions. A previous study [44] has shown that patients with less education, comorbidities, and chemotherapy were more likely to possess poor QoL, while the lack of social support and unmet needs may have led to poor health-related QoL. Moreover, increasing the range of cognitive adaptations may improve the QoL of cancer survivors who experience CRCI [45]. Baduanjin exercise could improve QoL and promote the recovery of the shoulder joint function among postoperative BC patients, especially the active range of movement of the shoulder joint. These results were consistent with those of Ying et al. [19]. Another randomized controlled trial [46] also found that QoL of patients in the Baduanjin group was better than that of the control group, and QoL positively correlated with anxiety and depression. In addition, one study showed that Baduanjin affected increasing BMI and relieving postoperative limb pain and lymphatic swelling [47], but significant differences in BMI and pain between the two groups were not observed in our study. This may be because in most of the patients, lymphatic—majorly sentinel—dissection was used. Less axillary dissection was performed, and some BC patients underwent breast-conserving surgery, without obvious postoperative pain. Second, lymphedema generally appeared 3 to 6 months after the operation, and no obvious limb swelling was found in the two groups of patients. Therefore, a 3-month follow-up after the end of the intervention is recommended to observe the changes in these indicators in future studies to explore these problems.

Anxiety symptoms and fatigue mediate the exercise-cognition relationship

Self-reported cognitive impairment has been associated with poor physical function and worse mental health, which is more likely to occur and even worsen in cancer patients [48]. A longitudinal observational study found that worry and fatigue play a role in the relationship between physical activity and subjective cognition [49]. Another study [50] showed that in postmenopausal BC patients treated with aromatase inhibitors, the severity of cognitive impairment increased with the degree of insomnia. Sleep disturbance may also be an influencing factor of CRCI, but this study did not follow up on the sleep quality. In addition, Song and Yu [51] showed that aerobic exercise could improve the quality of sleep and reduce depression in elderly individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Physical activity affects cognition by increasing the level of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in plasma, improving metabolic function, and reducing systemic inflammation [52]. The level of BDNF is related to processing speed and increases significantly after aerobic exercise [53]. Future research may further explore changes of cognition in brain tissue and its function, immunohistochemistry to contribute to the study of the mechanism by which exercise improves cognitive function. It also needs to be further determined whether the management strategy of CRCI can be improved by solving fatigue, anxiety, or sleep problems.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, this study considered the research characteristics of exercise intervention, and it was impossible to blind the subjects and Baduanjin practitioners, so we only blinded the outcome assessors. Second, the research objects were patients receiving chemotherapy in the period of postoperative recovery; as they were affected by surgical trauma, BC patients could less easily perform a standard range of body movements at the initial stage. Although some exercises improved, after all, the initial modified exercises were still different from the original standardized exercises, which may have affected the results. Although in this study we explored the role of fatigue and anxiety in exercise and cognition, we did not examine whether sleep had a mediating role in exercise and cognition, which may be considered in future studies. In addition, the sample size of this study was not large, and the interpretation of the results had certain limitations. A larger sample can be considered in the next study. Finally, taking into account the limited funds, we did not collect the laboratory indicators related to cognition; such indicators may be included as a part of mechanism research in the future, and the effects of exercise on CRCI can be further enriched through multidisciplinary examination, including medical imaging.

Conclusion

This study presented positive outcomes of a 12-week Baduanjin exercise program for protection against cognitive decline and improvement of QoL among BC patients receiving chemotherapy. Furthermore, decreasing anxiety and improving fatigue were identified as a part of the possible mechanism underlying the exercise-cognition relationship. The effectiveness and feasibility of this exercise program also promoted the need to increase its application to prevent further cognitive decline in BC patients.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Code availability

N/A.

References

TA Ahles AJ Saykin BC McDonald Y Li CT Furstenberg BS Hanscom TJ Mulrooney GN Schwartz PA Kaufman 2010 Longitudinal assessment of cognitive changes associated with adjuvant treatment for breast cancer: impact of age and cognitive reserve J Clin Oncol 28 29 4434 4440

F Joly B Giffard O Rigal MB Ruiter De BJ Small M Dubois J LeFel SB Schagen TA Ahles JS Wefel JL Vardy V Pancre M Lange H Castel 2015 Impact of cancer and its treatments on cognitive function: advances in research from the Paris International Cognition and Cancer Task Force symposium and update since 2012 J Pain Symptom Manage 50 6 830 841

M Lange F Joly 2017 How to identify and manage cognitive dysfunction after breast cancer treatment J Oncol Pract 13 12 784 790

MG Falleti A Sanfilippo P Maruff L Weih KA Phillips 2005 The nature and severity of cognitive impairment associated with adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer: a meta-analysis of the current literature Brain Cogn 59 1 60 70

JE Schmidt E Beckjord DH Bovbjerg CA Low DM Posluszny AE Lowery MA Dew S Nutt SR Arvey R Rechis 2016 Prevalence of perceived cognitive dysfunction in survivors of a wide range of cancers: results from the 2010 LIVESTRONG survey J Cancer Surviv 10 2 302 311

M Lange I Licaj B Clarisse X Humbert JM Grellard L Tron F Joly 2019 Cognitive complaints in cancer survivors and expectations for support: results from a web-based survey Cancer Med 8 5 2654 2663

C Robb D Boulware J Overcash M Extermann 2010 Patterns of care and survival in cancer patients with cognitive impairment Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 74 3 218 224

YT Cheung T Ng M Shwe HK Ho KM Foo MT Cham JA Lee G Fan YP Tan WS Yong P Madhukumar SK Loo SF Ang M Wong WY Chay WS Ooi RA Dent YS Yap R Ng A Chan 2015 Association of proinflammatory cytokines and chemotherapy-associated cognitive impairment in breast cancer patients: a multi-centered, prospective, cohort study Ann Oncol 26 7 1446 1451

S Kesler M Janelsins D Koovakkattu O Palesh K Mustian G Morrow FS Dhabhar 2013 Reduced hippocampal volume and verbal memory performance associated with interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels in chemotherapy-treated breast cancer survivors Brain Behav Immun 30 Suppl S109 116

BL Pierce R Ballard-Barbash L Bernstein RN Baumgartner ML Neuhouser MH Wener KB Baumgartner FD Gilliland BE Sorensen A McTiernan CM Ulrich 2009 Elevated biomarkers of inflammation are associated with reduced survival among breast cancer patients J Clin Oncol 27 21 3437 3444

JK Vulpen van ME Schmidt MJ Velthuis J Wiskemann A Schneeweiss RCH Vermeulen N Habermann CM Ulrich PHM Peeters E Wall van der AM May K Steindorf 2018 Effects of physical exercise on markers of inflammation in breast cancer patients during adjuvant chemotherapy Breast Cancer Res Treat 168 2 421 431

N Mounier A Abdel-Maged S Wahdan A Gad S Azab 2020 Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment (CICI): an overview of etiology and pathogenesis Life Sci 258 118071

CM Schilder C Seynaeve SC Linn W Boogerd LV Beex CM Gundy JW Nortier CJ Velde van de FS Dam van SB Schagen 2012 Self-reported cognitive functioning in postmenopausal breast cancer patients before and during endocrine treatment: findings from the neuropsychological TEAM side-study Psychooncology 21 5 479 487

S Menning MB Ruiter de DJ Veltman W Boogerd HS Oldenburg L Reneman SB Schagen 2017 Changes in brain activation in breast cancer patients depend on cognitive domain and treatment type PLoS One 12 3 e0171724

N Biglia VE Bounous A Malabaila D Palmisano DM Torta M D'Alonzo P Sismondi R Torta 2012 Objective and self-reported cognitive dysfunction in breast cancer women treated with chemotherapy: a prospective study Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 21 4 485 492

N Rosa De L Della Corte A Giannattasio P Giampaolino C Carlo Di G Bifulco 2021 Cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI), depression and quality of life in gynecological cancer patients: a prospective study Arch Gynecol Obstet 303 6 1581 1588

M Jia X Zhang L Wei J Gao 2021 Measurement, outcomes and interventions of cognitive function after breast cancer treatment: a narrative review Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 17 4 321 329

Y Lu HQ Qu FY Chen XT Li L Cai S Chen YY Sun 2019 Effect of Baduanjin Qigong exercise on cancer-related fatigue in patients with colorectal cancer undergoing chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial Oncol Res Treat 42 9 431 439

W Ying Q Min T Lei Z Na L Li L Jing 2019 The health effects of Baduanjin exercise (a type of Qigong exercise) in breast cancer survivors: a randomized, controlled, single-blinded trial Eur J Oncol Nurs 39 90 97

L Zou Z Pan A Yeung S Talwar C Wang Y Liu Y Shu X Chen GA Thomas 2018 A review study on the beneficial effects of Baduanjin J Altern Complement Med 24 4 324 335

J Tao J Liu X Chen R Xia M Li M Huang S Li J Park G Wilson C Lang G Xie B Zhang G Zheng L Chen J Kong 2019 Mind-body exercise improves cognitive function and modulates the function and structure of the hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex in patients with mild cognitive impairment NeuroImage Clin 23 101834

R Xia P Qiu H Lin B Ye M Wan M Li J Tao L Chen G Zheng 2019 The effect of traditional Chinese mind-body exercise (Baduanjin) and brisk walking on the dorsal attention network in older adults with mild cognitive impairment Front Psychol 10 2075

DK Ehlers S Aguinaga J Cosman J Severson AF Kramer E McAuley 2017 The effects of physical activity and fatigue on cognitive performance in breast cancer survivors Breast Cancer Res Treat 165 3 699 707

SJ Hartman SH Nelson E Myers L Natarajan DD Sears BW Palmer LS Weiner BA Parker RE Patterson 2018 Randomized controlled trial of increasing physical activity on objectively measured and self-reported cognitive functioning among breast cancer survivors: the memory & motion study Cancer 124 1 192 202

CR Marinac S Godbole J Kerr L Natarajan RE Patterson SJ Hartman 2015 Objectively measured physical activity and cognitive functioning in breast cancer survivors J Cancer Surviv 9 2 230 238

K Campbell J Kam S Neil-Sztramko T Liu Ambrose T Handy H Lim S Hayden L Hsu A Kirkham C Gotay D McKenzie L Boyd 2018 Effect of aerobic exercise on cancer-associated cognitive impairment: a proof-of-concept RCT Psychooncology 27 1 53 60

DA Galvao DR Taaffe N Spry D Joseph RU Newton 2010 Combined resistance and aerobic exercise program reverses muscle loss in men undergoing androgen suppression therapy for prostate cancer without bone metastases: a randomized controlled trial J Clin Oncol 28 2 340 347

TC Koh 1982 Baduanjin — an ancient Chinese exercise Am J Chin Med 10 1–4 14 21

X Chen G Marrone TP Olson CS Lundborg H Zhu Z Wen W Lu W Jiang 2020 Intensity level and cardiorespiratory responses to Baduanjin exercise in patients with chronic heart failure ESC Heart Fail 7 6 3782 3791

JS Myers M Mitchell S Krigel A Steinhoff A Boyce-White K Goethem Van M Valla J Dai J He W Liu SM Sereika CM Bender 2019 Qigong intervention for breast cancer survivors with complaints of decreased cognitive function Support Care Cancer 27 4 1395 1403

D Riebe. ACSMs guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2018 61 68

XL Wei RZ Yuan YM Jin S Li MY Wang JT Jiang CQ Wu KP Li 2021 Effect of Baduanjin exercise intervention on cognitive function and quality of life in women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial Trials 22 1 405

B Oh PN Butow BA Mullan SJ Clarke PJ Beale N Pavlakis MS Lee DS Rosenthal L Larkey J Vardy 2012 Effect of medical Qigong on cognitive function, quality of life, and a biomarker of inflammation in cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial Support Care Cancer 20 6 1235 1242

ZF Jiang JB Li 2020 Development of guidelines and clinical practice for breast cancer Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 58 2 85 90

LI Wagner J Sweet Z Butt JS Lai D Cella 2009 Measuring patient self-reported cognitive function: development of the functional assessment of cancer therapy–cognitive function instrument J Support Oncol 7 W32 W39

KD Stein SC Martin DM Hann PB Jacobsen 1998 A multidimensional measure of fatigue for use with cancer patients Cancer Pract 6 3 143 152

LC Pien H Chu WC Chen YS Chang YM Liao CH Chen KR Chou 2011 Reliability and validity of a Chinese version of the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-SF-C) J Clin Nurs 20 15–16 2224 2232

A Zigmond R Snaith 1983 The hospital anxiety and depression scale Acta Psychiatr Scand 67 6 361 370

MJ Brady DF Cella F Mo AE Bonomi DS Tulsky SR Lloyd S Deasy M Cobleigh G Shiomoto 1997 Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast quality-of-life instrument J Clin Oncol 15 3 974 986

CR Constant AH Murley 1987 A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder Clin Orthop Relat Res 214 160 164

AF Hayes NJ Rockwood 2017 Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation Behav Res Ther 98 39 57

KJ Preacher AF Hayes 2004 SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 36 4 717 731

HM Derry LM Jaremka JM Bennett J Peng R Andridge C Shapiro WB Malarkey CF Emery R Layman E Mrozek R Glaser JK Kiecolt-Glaser 2015 Yoga and self-reported cognitive problems in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial Psychooncology 24 8 958 966

P Ho S Gernaat M Hartman H Verkooijen 2018 Health-related quality of life in Asian patients with breast cancer: a systematic review BMJ open 8 4 e020512

HJ Green ME Mihuta T Ownsworth HM Dhillon M Tefay J Sanmugarajah HW Tuffaha SK Ng DHK Shum 2019 Adaptations to cognitive problems reported by breast cancer survivors seeking cognitive rehabilitation: a qualitative study Psychooncology 28 10 2042 2048

P Liu J You W Loo Y Sun Y He H Sit L Jia M Wong Z Xia X Zheng Z Wang N Wang L Lao J Chen 2017 The efficacy of Guolin-Qigong on the body-mind health of Chinese women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial Qual Life Res 26 9 2321 2331

D Panchik S Masco P Zinnikas B Hillriegel T Lauder E Suttmann V Chinchilli M McBeth W Hermann 2019 Effect of exercise on breast cancer-related lymphedema: what the lymphatic surgeon needs to know J Reconstr Microsurg 35 1 37 45

J Mariegaard J Wenstrup KZM Lim PE Bidstrup A Heymann von C Johansen GM Knudsen I Law L Specht DS Stenbæk 2021 Prevalence of cognitive impairment and its relation to mental health in Danish lymphoma survivors Support Care Cancer 29 6 3319 3328

S Phillips G Lloyd E Awick E McAuley 2017 Relationship between self-reported and objectively measured physical activity and subjective memory impairment in breast cancer survivors: role of self-efficacy, fatigue and distress Psychooncology 26 9 1390 1399

KT Liou TA Ahles SN Garland QS Li T Bao Y Li JC Root JJ Mao 2019 The relationship between insomnia and cognitive impairment in breast cancer survivors JNCI Cancer Spectr 3 3 pkz041

D Song D Yu 2019 Effects of a moderate-intensity aerobic exercise programme on the cognitive function and quality of life of community-dwelling elderly people with mild cognitive impairment: a randomised controlled trial Int J Nurs Stud 93 97 105

M Shahid J Kim 2020 Exercise may affect metabolism in cancer-related cognitive impairment Metabolites 10 9 377

K Szuhany M Bugatti M Otto 2015 A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor J Psychiatr Res 60 56 64

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all participants who contribute to the trial.

Funding

The trial was supported by the Nursing Subject Competence Enhancement Project of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 2020HLXK07) and Xinglin Youth Talents Training Project of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine-Xinglin Scholar to Caiqin Wu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology: Wu Caiqin; data curation, writing—original draft preparation: Wei Xiaolin; visualization, investigation: Jiang Jieting, Wang Mingyue; supervision: Yang Juan, Jin Yongmei, Zheng Wei; software, validation: Yuan Ruzhen; writing—reviewing and editing: Li Kunpeng. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Seventh People’s Hospital of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 2020-7th-HIRB-011).

Consent to participate

All participants provided informed consent prior to enrolling onto the study.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of this manuscript in Supportive Care in Cancer.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, X., Yuan, R., Yang, J. et al. Effects of Baduanjin exercise on cognitive function and cancer-related symptoms in women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 30, 6079–6091 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07015-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07015-4