Abstract

Background

Aromatase inhibitor induced musculoskeletal syndrome is experienced by approximately half of women taking aromatase inhibitors, impairing quality of life and leading some to discontinue treatment. Evidence for effective treatments is lacking. We aimed to understand the manifestations and impact of this syndrome in the Australian breast cancer community, and strategies used for its management.

Methods

A survey invitation was sent to 2390 members of the Breast Cancer Network Australia Review and Survey Group in April 2014. The online questionnaire included 45 questions covering demographics, aromatase inhibitor use, clinical manifestations and risk factors for the aromatase inhibitor musculoskeletal syndrome, reasons for treatment discontinuation and efficacy of interventions used.

Results

Aromatase inhibitor induced musculoskeletal syndrome was reported by 302 (82 %) of 370 respondents. Twenty-seven percent had discontinued treatment for any reason and of these, 68 % discontinued because of the musculoskeletal syndrome. Eighty-one percent had used at least one intervention from the following three categories to manage the syndrome: doctor prescribed medications, over-the-counter/complementary medicines or alternative/non-drug therapies. Anti-inflammatories, paracetamol (acetaminophen) and yoga were most successful in relieving symptoms in each of the respective categories. Almost a third of respondents reported that one or more interventions helped prevent aromatase inhibitor discontinuation. However, approximately 20 % of respondents found no intervention effective in any category.

Conclusion

We conclude that aromatase inhibitor induced musculoskeletal syndrome is a significant issue for Australian women and is an important reason for treatment discontinuation. Women use a variety of interventions to manage this syndrome; however, their efficacy appears limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The aromatase inhibitors (AIs) letrozole, anastrozole and exemestane have become an important treatment option for postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer, after publication of studies demonstrating a relapse-free survival benefit over tamoxifen [1–3]. Musculoskeletal symptoms, including arthritis, arthralgia, myalgia, musculoskeletal pain, joint stiffness and paraesthesia (e.g., carpal tunnel syndrome) are known adverse effects associated with this class of drug, and the term aromatase inhibitor musculoskeletal syndrome (AIMSS) has been coined by Lintermans and colleagues to describe this spectrum of symptoms [4].

Clinical trials of adjuvant endocrine therapy report arthralgia rates of between 20 and 36.5 % for AIs, compared with 13–30 % for tamoxifen [1–3]. In the prevention setting, the IBIS II study reported musculoskeletal adverse events in 64 % of those in the anastrozole group compared with 58 % of those in the placebo group [5]. The heterogeneity of results seen in these large randomised trials is probably due to a lack of standardised definition and reporting of musculoskeletal symptoms, resulting in an under-estimation of the incidence. In community-based samples, the rate of musculoskeletal symptoms is generally considerably higher: reported in up to 80 % of patients and associated with a discontinuation rate of up to 25 % [6–9]. AIMSS has been cited as the reason for AI discontinuation for 50–80 % of patients [10, 11].

Early discontinuation and suboptimal adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy is associated with decreased disease-free survival and increased mortality, suggesting that improving adherence will lead to improved breast cancer outcomes [12–17]. Although post hoc analyses of the MA.27 [18] and IES [19] studies did not show an association between musculoskeletal adverse events and improved survival, the analysis of three large datasets (ATAC [20], TEAM [21] and BIG 1-98 [22]) did reveal an association. Therefore, strategies to manage AIMSS are needed to optimise the use of AIs in order to improve breast cancer outcomes and quality of life.

Despite nearly 10 years of investigation, few studies have identified efficacious interventions for AIMSS. Small randomised studies have shown a benefit from acupuncture [23, 24], exercise [25] and vitamin D [26]. Several single-arm studies suggest possible benefit from glucosamine sulphate with chondroitin [27], prednisolone [28] and duloxetine [29]. Other strategies have been extrapolated from the management of osteoarthritis despite the apparent differences in the mechanism and clinical manifestations of AIMSS.

Breast cancer in Australia is similar to this disease in other developed countries. The age-adjusted incidence rate is 60 per 100,000 with a 10-year survival rate of 83 %. The majority of breast cancer is oestrogen and/or progesterone receptor positive and most women will be offered endocrine therapy for early-stage breast cancer [30]. In Australia, in 2011, 378,990 Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme prescriptions were filled for AIs, almost exclusively for 1-month supply each [31]. This represents a large group of patients exposed to a potential toxicity burden. Given the large numbers of women who are prescribed AIs and the potential for AIMSS to lead to AI discontinuation and poorer breast cancer outcomes, we aimed to gain an understanding of the manifestations and impact of AIMSS in the Australian breast cancer community. We were particularly interested in identifying what interventions women use to manage AIMSS (both conventional medications and complementary or alternative strategies). No Australian literature and limited international literature exists on this topic. The aim of our study was to inform a future intervention study.

Methods

This study used a cross-sectional observational design. An e-mail survey invitation was sent to 2390 members of the Breast Cancer Network Australia (BCNA) Review and Survey Group in April 2014, with a reminder 2 weeks later. All recipients were listed in the BCNA database as having early-stage invasive breast cancer. The e-mail contained information about the study and a link to an online questionnaire. After consenting to participate, respondents were screened for eligibility. Eligible participants were adult females, with a diagnosis of early-stage (I–III) invasive breast cancer from 2007 onwards and current or past AI use. Respondents were excluded if they reported a history of carcinoma in situ without invasive breast cancer, or of metastatic breast cancer. The online questionnaire consisted of 45 questions covering demographics, use of AIs and tamoxifen, clinical manifestations and risk factors for AIMSS, reasons for AI discontinuation, and efficacy of interventions used for AIMSS. AIMSS was defined as joint pain or stiffness that developed or worsened after commencing an AI.

This was a descriptive study. We hypothesized that >50 % of respondents would describe AIMSS, that AIMSS would be the main reason for AI discontinuation in >50 % of respondents, and <20 % of respondents would report a benefit from any one intervention. The pre-specified analysis plan included descriptive summary measures of each questionnaire item. A multivariate logistic regression model was fit including potential predictors of AIMSS. Missing data were corrected using mean imputation.

This study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. It was approved by the Hunter New England Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee. It is registered on the Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au), number ACTRN12613001009707.

Results

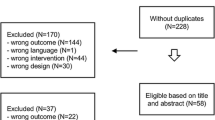

Of the 2390 members of the BCNA Review and Survey Group invited to participate, 594 responded (25 %). In total 370 participant questionnaires were eligible for analysis. Reasons for exclusion were: pre-invasive disease, metastatic disease, diagnosis before 2007 and no exposure to AI (Fig. 1). Ninety percent of eligible respondents completed >90 % of the questionnaire.

Eligible respondents had a median age range of 50–59 years and resided in all states and territories of Australia (Table 1). Most lived within metropolitan areas (58 %). More than half had received adjuvant chemotherapy, of which 43 % commenced AI within 3 months of chemotherapy and 30 % within 3–6 months of chemotherapy. Adjuvant tamoxifen was used by a third of patients prior to commencing an AI. Duration of AI use varied with 26 % of respondents having used less than 1 year, 64 % 1 to 5 years and 10 % greater than 5 years of therapy. The median duration of AI use was 25 months. As joint pain associated with menopause is common, we asked respondents if they had experienced this (prior to commencing AI). Twenty-five percent reported menopausal arthralgia, 50 % no arthralgia and 25 % could not recall if it was present or not.

In light of the data supporting a role for vitamin D replacement in reducing AIMSS [26], respondents were asked about vitamin D testing and treatment. Most respondents (70 %) had vitamin D levels checked, and 75 % were currently taking vitamin D supplements. Sixty-six percent of patients self-reported adequate vitamin D levels (≥60 nmol/L), 19 % intermediate (40–59 nmol/L) and 15 % low (<40 nmol/L).

AIMSS was reported by 82 % of respondents (95 % CI 77–85 %). Sites affected included feet (68 %), hands or wrists (65 %), knees (62 %), hips (56 %) shoulders or elbows (49 %), back (46 %) or neck (3 %). AIMSS was self-classified mild (no impact on daily activities) in 23 %, moderate (troubling, but still able to perform daily activities) in 57 % and severe (preventing ability to perform activities of daily living) in 20 %. The incidence of AIMSS was no different with anastrozole, letrozole or exemestane.

The following factors were assessed as predictors of AIMSS in univariate analysis: receipt of taxane chemotherapy, pre-existing joint, muscle or tendon pain, low vitamin D level (<40 nmol/L) and joint pain during menopause. In a multivariate logistic regression model, receipt of taxane chemotherapy (p = 0.006) and pre-existing joint, muscle or tendon pain (p < 0.001) were the only significant predictors of AIMSS (Table 2). Joint symptoms during menopause were of borderline significance (p = 0.05).

Discontinuation

One third of women had considered stopping an AI because of AIMSS. Twenty-seven percent of respondents had discontinued AI for any reason, and of these, 68 % (95 % CI 59–77 %) discontinued because of AIMSS. Non-AIMSS reasons for discontinuation included fatigue, genitourinary symptoms and hot flushes (Fig. 2).

More than half of the women who discontinued AI because of AIMSS did not switch to an alternative AI. A small number (17 %) took tamoxifen after AI discontinuation. Numbers were too small to ascertain whether changing to an alternative AI or to tamoxifen resulted in a lower AIMSS burden.

Interventions

A variety of interventions were utilized to manage AIMSS (Table 3). These were grouped into three categories: doctor prescribed medications, over-the-counter/complementary medicines and alternative/ non-drug interventions. A total of 245 (81 %) of those with AIMSS had used at least one intervention: 27 % had used a doctor prescribed medication, 65 % had used an over-the-counter/complementary medicine, and 35 % had used an alternative/ non-drug intervention to manage AIMSS symptoms.

The effectiveness of these interventions was typically low (Fig. 3a–c). Prescription anti-inflammatories were the most commonly used and effective intervention in the doctor prescribed medication (DPM) category. Of 86 respondents who had used a DPM, 73 % had used anti-inflammatories and of these, 62 % found it reduced AIMSS symptoms. Twenty-one percent of respondents did not find that any DPM was effective for AIMSS. Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) was the most commonly used over-the-counter/complementary medicine (OTC/CAM) intervention (33 %) with 37 % finding it helpful for AIMSS. In this category, 17 % found no OTC/CAM effective for AIMSS symptoms. In the alternative/non-drug intervention group, 33 % had trialled an intervention for AIMSS. Twenty percent found yoga effective, 21 % found “other interventions” effective (including exercise, physiotherapy, Bowen therapy and a number of other interventions), and 18 % found no intervention of any value.

Overall 27 % (95 % CI 21–33 %) of respondents who had used at least one intervention for AIMSS found that the intervention(s) had helped them to continue taking an AI. Eighteen percent did not find an intervention from any category that reduced the severity of their AIMSS symptoms.

Severity of joint pain was not associated with effectiveness of any therapy. Respondents with mild/moderate pain were no more (or less) likely to experience benefit from any intervention, compared with those who experienced severe pain (χ 2 = 0.6177, p = 0.432).

Discussion

Our study confirmed two of our three hypotheses: >50 % of patients reported AIMSS and >50 % of discontinuations were for this reason. Overall, interventions were more effective in reducing AIMSS symptoms than we hypothesized. The most effective intervention reported was doctor prescribed anti-inflammatories, with more than 50 % benefitting. The study also highlighted that women use a range of interventions to manage AIMSS. It was hoped that this study may identify a possible intervention for future study; however, in our opinion, no intervention emerged as a clear candidate for further study as the efficacy of all the interventions were low.

The 27 % rate of AI discontinuation seen in this observational community cohort of Australian women with early breast cancer is similar to the 13–25 % rates seen in other series [6, 7, 9, 32, 33]. In our series, 27 % had discontinued AI for any reason and for 68 % this was due to AIMSS. However, our patient cohort may have been enriched for incidence and severity of AIMSS because of self-selection. Our identified predictors of AIMSS are consistent with previous series. Prior taxane exposure, prior hormone replacement therapy and pre-existing pain, fatigue, low mood and sleep disruption have been identified as predictors [7, 19, 34, 35]. There is conflicting data on the relationship with baseline weight. Obesity in some series appears to increase risk whilst in others is protective [36].

Our results also highlight the wide variety of interventions that women use to manage AIMSS. Almost three quarters of respondents in our series had utilized non-doctor prescribed medications and/or non-drug interventions to try to manage AIMSS. The effectiveness of any individual AIMSS management strategy was low. Doctor prescribed anti-inflammatories were the only intervention that more than 50 % of respondents reported as having reduced their symptoms. However, prescription anti-arthralgia medication has not been shown to assist with AI therapy persistence [37]. Many individual strategies were considered ineffective in our sample, but only 18 % of respondents found no intervention/medication of any value. The effectiveness of combinations of treatments is of interest, but this was not recorded in our study.

The mechanism by which AIs cause AIMSS is not well understood, but it is considered likely that estrogen deprivation is the key mediator. Arthralgia and other symptoms of AIMSS are seen in 50 % of women at the time of natural menopause, and in some, an acceleration of osteoarthritis occurs [38]. Oestrogen receptors are found in bone, cartilage and synovial cells, and oestrogen can reduce release of tissue necrosis factor (TNF) α and interleukin (IL)-1β involved in inflammatory arthritides [39]. Oestrogen is also known to play an important role in joint integrity via its maintenance of collagen, cartilage and bone health [40] and its anti-nociceptive effects within the central nervous system [41]. At a cellular level, the mechanism of AIMSS remains elusive: inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines although most likely to play a role, have not been shown to be elevated systemically [42] suggesting that local inflammatory molecules or other as yet unproven factors may be key such as insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-1) which is elevated in AIMSS [4]. Recently, it has been shown that IGF-1 is increased with AI use and IGF binding protein 3 elevation is associated with AIMSS [43]. Despite wide interest and need, and considerable research, to date, no treatable target has been identified that would suggest an effective management strategy for AIMSS.

Currently, only four published randomised controlled trials support a potential intervention for AIMSS control. The studies by Crew et al. and Mao et al. both showed that acupuncture (in a blinded study versus sham acupuncture) reduced pain scores at 6 weeks [23] and at 8 and 12 weeks [24]. Rastelli et al. conducted a phase 2 study that showed high dose vitamin D reduced pain scores at 2 months compared with placebo; however, the benefit was not persistent [44]. Irwin et al. randomised 121 physically inactive women who were currently receiving an AI and who reported AIMSS to an exercise intervention versus usual care over 12 months [25]. Pain severity reduced significantly in the exercise intervention arm. In our series, only 14 women reported using exercise as an intervention for AIMSS; however, it may have been underreported because exercise was not listed as a defined choice in the survey. The role of exercise warrants further research.

Several single-arm studies examining vitamin D supplementation have demonstrated reduced joint pain in patients who achieved higher vitamin D levels [45, 46]. This may be explained by the apparent association between AIMSS and single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes related to vitamin D and oestrogen signalling [47]. In our series, most patients (66 %) reported adequate vitamin D levels (>60 nmol/L).

Prednisolone, duloxetine and glucosamine sulphate with chondroitin have also been evaluated in single-arm studies in which most patients reported a reduction in pain or pain scores [27–29]. Randomised data for these agents, however, is not available.

Yoga was associated with a reduction in pain and increased flexibility in a single-arm study of ten postmenopausal women with AIMSS [25, 48]. There is indirect evidence that weight loss may reduce menopausal arthralgia [38].

Our study is limited by the retrospective and descriptive nature of the data and the potential for selection bias including bias in respondent self-report and recall. The definition of AIMSS (joint pain or stiffness that developed or worsened after commencing an AI) was pragmatic for purposes of the survey and may have overestimated the rate of AIMSS in the sample. Despite these shortcomings the numbers of respondents reporting AIMSS and discontinuing AI is consistent with the existing literature.

Conclusion

This survey confirms that AIMSS is a significant issue for Australian women with early breast cancer and an important reason for AI discontinuation. Women use many different interventions to manage AIMSS; however, their efficacy appears limited. The identification of effective AIMSS interventions remains a priority for future research and possibly further research into the pathogenesis of AIMSS may inform best what the most scientific intervention for future study may be.

References

Coates AS, Keshaviah A, Thürlimann B, Mouridsen H, Mauriac L, Forbes JF, Paridaens R, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Gelber RD, Colleoni M, Láng I, Del Mastro L, Smith I, Chirgwin J, Nogaret J-M, Pienkowski T, Wardley A, Jakobsen EH, Price KN, Goldhirsch A (2007) Five years of letrozole compared with tamoxifen as initial adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer: update of study BIG 1-98. J Clin Oncol 25(5):486–492. doi:10.1200/jco.2006.08.8617

Coombes RC, Kilburn LS, Snowdon CF, Paridaens R, Coleman RE, Jones SE, Jassem J, Van de Velde CJH, Delozier T, Alvarez I, Del Mastro L, Ortmann O, Diedrich K, Coates AS, Bajetta E, Holmberg SB, Dodwell D, Mickiewicz E, Andersen J, Lønning PE, Cocconi G, Forbes J, Castiglione M, Stuart N, Stewart A, Fallowfield LJ, Bertelli G, Hall E, Bogle RG, Carpentieri M, Colajori E, Subar M, Ireland E, Bliss JM (2007) Survival and safety of exemestane versus tamoxifen after 2–3 years’ tamoxifen treatment (Intergroup Exemestane Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 369(9561):559–570

The Arimidex TAoiCATG (2008) Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 100-month analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 9(1):45–53. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70385-6

Lintermans A, Van Calster B, Van Hoydonck M, Pans S, Verhaeghe J, Westhovens R, Henry NL, Wildiers H, Paridaens R, Dieudonné AS, Leunen K, Morales L, Verschueren K, Timmerman D, De Smet L, Vergote I, Christiaens MR, Neven P (2011) Aromatase inhibitor-induced loss of grip strength is body mass index dependent: hypothesis-generating findings for its pathogenesis. Ann Oncol 22(8):1763–1769. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq699

Cuzick J, Sestak I, Forbes JF, Dowsett M, Knox J, Cawthorn S, Saunders C, Roche N, Mansel RE, von Minckwitz G, Bonanni B, Palva T, Howell A (2014) Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (IBIS-II): an international, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 383(9922):1041–1048. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62292-8

Briot K, Tubiana-Hulin M, Bastit L, Kloos I, Roux C (2010) Effect of a switch of aromatase inhibitors on musculoskeletal symptoms in postmenopausal women with hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer: the ATOLL (articular tolerance of letrozole) study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 120(1):127–134. doi:10.1007/s10549-009-0692-7

Henry NL, Azzouz F, Desta Z, Li L, Nguyen AT, Lemler S, Hayden J, Tarpinian K, Yakim E, Flockhart DA, Stearns V, Hayes DF, Storniolo AM (2012) Predictors of aromatase inhibitor discontinuation as a result of treatment-emergent symptoms in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 30(9):936–942. doi:10.1200/jco.2011.38.0261

Porter D (2013) New Zealand survey of aromatase inhibitor toxicity

Presant CA, Bosserman L, Young T, Vakil M, Horns R, Upadhyaya G, Ebrahimi B, Yeon C, Howard F (2007) Aromatase inhibitor–associated arthralgia and/or bone pain: frequency and characterization in non–clinical trial patients. Clin Breast Cancer 7(10):775–778. doi:10.3816/CBC.2007.n.038

Zivian MT, Salgado B (2008) Side effects revisitied: Women’s experiences with aromatase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Action, San Francisco

Lintermans A, Van Asten K, Wildiers H, Laenen A, Paridaens R, Weltens C, Verhaeghe J, Vanderschueren D, Smeets A, Van Limbergen E, Leunen K, Christiaens MR, Neven P (2014) A prospective assessment of musculoskeletal toxicity and loss of grip strength in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors and tamoxifen, and relation with BMI. Breast Cancer Res Treat 146(1):109–116. doi:10.1007/s10549-014-2986-7

Barron TI, Cahir C, Sharp L, Bennett K (2013) A nested case–control study of adjuvant hormonal therapy persistence and compliance, and early breast cancer recurrence in women with stage I-III breast cancer. Br J Cancer 109(6):1513–1521. doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.518

Chirgwin J, Giobbie-Hurder A. Treatment adherence in the BIG 1-98 trial of tamoxifen, letrozole alone and in sequence

Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, Buono D, Tsai WY, Fehrenbacher L, Kwan M, Gomez SL, Neugut AI (2011) Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 126(2):529–537. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-1132-4

Makubate B, Donnan PT, Dewar JA, Thompson AM, McCowan C (2013) Cohort study of adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy, breast cancer recurrence and mortality. Br J Cancer 108(7):1515–1524. doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.116

McCowan C, Shearer J, Donnan PT, Dewar JA, Crilly M, Thompson AM, Fahey TP (2008) Cohort study examining tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer 99(11):1763–1768. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604758

McCowan C, Wang S, Thompson AM, Makubate B, Petrie DJ (2013) The value of high adherence to tamoxifen in women with breast cancer: a community-based cohort study. Br J Cancer 109(5):1172–1180. doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.464

Stearns V, Chapman JA, Ma CX, Ellis MJ, Ingle JN, Pritchard KI, Budd GT, Rabaglio M, Sledge GW, Le Maitre A, Kundapur J, Liedke PE, Shepherd LE, Goss PE (2015) Treatment-associated musculoskeletal and vasomotor symptoms and relapse-free survival in the NCIC CTG MA.27 adjuvant breast cancer aromatase inhibitor trial. J Clin Oncol 33(3):265–271. doi:10.1200/jco.2014.57.6926

Mieog JS, Morden JP, Bliss JM, Coombes RC, van de Velde CJ (2012) Carpal tunnel syndrome and musculoskeletal symptoms in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer treated with exemestane or tamoxifen after 2–3 years of tamoxifen: a retrospective analysis of the Intergroup Exemestane Study. Lancet Oncol 13(4):420–432. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70328-x

Cuzick J, Sestak I, Cella D, Fallowfield L (2008) Treatment-emergent endocrine symptoms and the risk of breast cancer recurrence: a retrospective analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 9(12):1143–1148. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70259-6

Fontein DB, Seynaeve C, Hadji P, Hille ET, van de Water W, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Hasenburg A, Paridaens RJ, Vannetzel JM, Markopoulos C, Hozumi Y, Bartlett JM, Jones SE, Rea DW, Nortier JW, van de Velde CJ (2013) Specific adverse events predict survival benefit in patients treated with tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors: an international tamoxifen exemestane adjuvant multinational trial analysis. J Clin Oncol 31(18):2257–2264. doi:10.1200/jco.2012.45.3068

Huober J, Cole BF, Rabaglio M, Giobbie-Hurder A, Wu J, Ejlertsen B, Bonnefoi H, Forbes JF, Neven P, Lang I, Smith I, Wardley A, Price KN, Goldhirsch A, Coates AS, Colleoni M, Gelber RD, Thurlimann B (2014) Symptoms of endocrine treatment and outcome in the BIG 1-98 study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 143(1):159–169. doi:10.1007/s10549-013-2792-7

Crew KD, Capodice JL, Greenlee H, Brafman L, Fuentes D, Awad D, Yann Tsai W, Hershman DL (2010) Randomized, blinded, sham-controlled trial of acupuncture for the management of aromatase inhibitor–associated joint symptoms in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 28(7):1154–1160. doi:10.1200/jco.2009.23.4708

Mao JJ, Xie SX, Farrar JT, Stricker CT, Bowman MA, Bruner D, DeMichele A (2014) A randomised trial of electro-acupuncture for arthralgia related to aromatase inhibitor use. Eur J Cancer 50(2):267–276. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.022

Irwin ML, Cartmel B, Gross CP, Ercolano E, Li F, Yao X, Fiellin M, Capozza S, Rothbard M, Zhou Y, Harrigan M, Sanft T, Schmitz K, Neogi T, Hershman D, Ligibel J (2015) Randomized exercise trial of aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 33(10):1104–1114. doi:10.1200/jco.2014.57.1547

Rastelli AL, Taylor ME, Villareal R, Jamalabadi-Majidi S, Gao F, Ellis MJ (2009) A double blind randomised placebo controlled trial of high dose vitamin D therapy on musculoskeletal pain and bone mineral density in anastrazole treated breast cancer patients with marginal vitamin D status. Paper presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, San Antonio

Greenlee H, Crew K, Shao T, Kranwinkel G, Kalinsky K, Maurer M, Brafman L, Insel B, Tsai W, Hershman D (2013) Phase II study of glucosamine with chondroitin on aromatase inhibitor-associated joint symptoms in women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 21(4):1077–1087. doi:10.1007/s00520-012-1628-z

Kubo M, Onishi H, Kuroki S, Okido M, Shimada K, Yokohata K, Umeda S, Ogawa T, Tanaka M, Katano M (2012) Short-term and low-dose prednisolone administration reduces aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia in patients with breast cancer. Anticancer Res 32(6):2331–2336

Henry NL, Banerjee M, Wicha M, Van Poznak C, Smerage JB, Schott AF, Griggs JJ, Hayes DF (2011) Pilot study of duloxetine for treatment of aromatase inhibitor-associated musculoskeletal symptoms. Cancer 117(24):5469–5475. doi:10.1002/cncr.26230

AIHW (2014) Cancer in Australia: an overview, 2014. vol Cancer series no. 90. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australasian Association of Cancer Registries, Canberra

Division PB (2011) Australian Statistics on Medicines. Commonwealth of Australia. http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/statistics/asm/asm-2011. Accessed 7 Jan 2015

Fontaine C, Meulemans A, Huizing M, Collen C, Kaufman L, De Mey J, Bourgain C, Verfaillie G, Lamote J, Sacre R, Schallier D, Neyns B, Vermorken J, De Grève J (2008) Tolerance of adjuvant letrozole outside of clinical trials. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland) 17(4):376–381

Henry N, Giles J, Ang D, Mohan M, Dadabhoy D, Robarge J, Hayden J, Lemler S, Shahverdi K, Powers P, Li L, Flockhart D, Stearns V, Hayes D, Storniolo AM, Clauw D (2008) Prospective characterization of musculoskeletal symptoms in early stage breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 111(2):365–372. doi:10.1007/s10549-007-9774-6

Kidwell KM, Harte SE, Hayes DF, Storniolo AM, Carpenter J, Flockhart DA, Stearns V, Clauw DJ, Williams DA, Henry NL (2014) Patient-reported symptoms and discontinuation of adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy. Cancer 120(16):2403–2411. doi:10.1002/cncr.28756

Sestak I, Cuzick J, Sapunar F, Eastell R, Forbes JF, Bianco AR, Buzdar AU (2008) Risk factors for joint symptoms in patients enrolled in the ATAC trial: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol 9(9):866–872. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70182-7

Crew KD, Greenlee H, Capodice J, Raptis G, Brafman L, Fuentes D, Sierra A, Hershman DL (2007) Prevalence of joint symptoms in postmenopausal women taking aromatase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 25(25):3877–3883. doi:10.1200/jco.2007.10.7573

Hashem MG, Cleary K, Fishman D, Nichols L, Khalid M (2013) Effect of concurrent prescription antiarthralgia pharmacotherapy on persistence to aromatase inhibitors in treatment-naive postmenopausal females. Ann Pharmacother 47(1):29–34. doi:10.1345/aph.1R369

Magliano M (2010) Menopausal arthralgia: fact or fiction. Maturitas 67(1):29–33. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.04.009

Tan AL, Emery P (2008) Role of oestrogen in the development of joint symptoms? Lancet Oncol 9(9):817–818. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70217-1

Richette P, Corvol M, Bardin T (2003) Estrogens, cartilage, and osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine 70(4):257–262. doi:10.1016/s1297-319x(03)00067-8

Felson DT, Cummings SR (2005) Aromatase inhibitors and the syndrome of arthralgias with estrogen deprivation. Arthritis Rheumatism 52(9):2594–2598. doi:10.1002/art.21364

Henry NL, Pchejetski D, A’Hern R, Nguyen AT, Charles P, Waxman J, Li L, Storniolo AM, Hayes DF, Flockhart DA, Stearns V, Stebbing J (2010) Inflammatory cytokines and aromatase inhibitor-associated musculoskeletal syndrome: a case–control study. Br J Cancer 103(3):291–296. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605768

Lintermans A, Vanderschueren D, Verhaeghe J, Van Asten K, Jans I, Van Herck E, Laenen A, Paridaens R, Billen J, Pauwels S, Vermeersch P, Wildiers H, Christiaens MR, Neven P (2014) Arthralgia induced by endocrine treatment for breast cancer: a prospective study of serum levels of insulin like growth factor-I, its binding protein and oestrogens. Eur J Cancer 50(17):2925–2931. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2014.08.012

Rastelli AL, Taylor ME, Gao F, Armamento-Villareal R, Jamalabadi-Majidi S, Napoli N, Ellis MJ (2011) Vitamin D and aromatase inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal symptoms (AIMSS): a phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 129(1):107–116. doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1644-6

Khan QJ, Reddy PS, Kimler BF, Sharma P, Baxa SE, O’Dea AP, Klemp JR, Fabian CJ (2010) Effect of vitamin D supplementation on serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels, joint pain, and fatigue in women starting adjuvant letrozole treatment for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 119(1):111–118. doi:10.1007/s10549-009-0495-x

Prieto-Alhambra D, Javaid MK, Servitja S, Arden NK, Martinez-Garcia M, Diez-Perez A, Albanell J, Tusquets I, Nogues X (2011) Vitamin D threshold to prevent aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia: a prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 125(3):869–878. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-1075-9

Garcia-Giralt N, Rodriguez-Sanz M, Prieto-Alhambra D, Servitja S, Torres-Del Pliego E, Balcells S, Albanell J, Grinberg D, Diez-Perez A, Tusquets I, Nogues X (2013) Genetic determinants of aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia: the B-ABLE cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 140(2):385–395. doi:10.1007/s10549-013-2638-3

Galantino ML, Desai K, Greene L, Demichele A, Stricker CT, Mao JJ (2012) Impact of yoga on functional outcomes in breast cancer survivors with aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgias. Integr Cancer Ther 11(4):313–320. doi:10.1177/1534735411413270

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants, the Breast Cancer Institute of Australia (BCIA) as the fundraising arm of the Australia and New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group (ANZBCTG), the ANZBCTG Trial Coordination Department and the Breast Cancer Network Australia for administering the survey.

Contribution

All authors have contributed to the planning and conduct of the study and the analysis of the data. All authors have approved the final submitted manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No authors had any conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

This study was funded by the Australia and New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group (ANZBCTG).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lombard, J.M., Zdenkowski, N., Wells, K. et al. Aromatase inhibitor induced musculoskeletal syndrome: a significant problem with limited treatment options. Support Care Cancer 24, 2139–2146 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3001-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3001-5